Published online Aug 21, 2023. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v29.i31.4809

Peer-review started: June 5, 2023

First decision: July 7, 2023

Revised: July 18, 2023

Accepted: July 31, 2023

Article in press: July 31, 2023

Published online: August 21, 2023

Processing time: 70 Days and 19.1 Hours

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (SRUS) is a rare rectal disease with unknown etiology. Data on the genetic background in SRUS is lacking.

Here, we report the first case of SRUS in a mother-son relationship. Gene sequ

SRUS is a genetic susceptibility disease where CHEK2 p.H371Y mutation may play a crucial role in the development and prognosis of SRUS.

Core Tip: Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (SRUS) is a rare rectal disease with unknown etiology. Data on the genetic background in SRUS is lacking. Here, we present the first case of SRUS in a mother-son relationship. Gene sequencing and experiment preliminarily indicate that SRUS may serve as a genetic susceptibility disease in which CHEK2 p.H371Y mutation may play a crucial role in the development and prognosis of SRUS. This case may offer some new insights into the virulence genes and genetic background of SRUS.

- Citation: He CC, Wang SP, Zhou PR, Li ZJ, Li N, Li MS. Inherited CHEK2 p.H371Y mutation in solitary rectal ulcer syndrome among familial patients: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2023; 29(31): 4809-4814

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v29/i31/4809.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v29.i31.4809

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (SRUS) is a chronic rectal disease characterized by difficulty in defecation, mucous hematochezia, and anal pain, and bulging. SRUS is a rare disease with unknown etiology that was proposed by Rutter in 1975[1]. We have a detailed understanding of the clinical, endoscopy, pathology and images characteristics based on recent reports about SRUS, but data about the etiology, especially the virulence genes and genetic background, are limited[2,3]. Herein, we present the first case that describes a Chinese female patient with SRUS and one of her sons diagnosed with SRUS. Her daughter and the other son demonstrated healthy gastrointestinal tracts. Next-generation sequencing of family inheritance results indicated an inherited CHEK2 p.H371Y mutation may contributes to SRUS.

A 63-year-old female patient was admitted to the Third Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University for abdominal pain, anal irritation, and repeated hematochezia. Her 31-year-old son was previously diagnosed with SRUS and underwent an inpatient examination.

Her symptoms started 1 year before the presentation of abdominal pain, anal irritation, and repeated hematochezia. Additionally, her 31-year-old son started to present with repeated diarrhea and intermittent hematochezia at the age of 26. He suffered from chronic diarrhea of up to 30 times a day, with the worst demonstrating fecal incontinence. He was subsequently diagnosed with SRUS 3 years ago and underwent surgical removal. The surgical pathology was consistent with the pathological features of SRUS (Supplementary Figure 1). Hematochezia disappeared postoperatively, but his diarrhea remained. Chronic diarrhea causes his anxiety because his symptoms worsen as his mood changed.

The patients were healthy before the SRUS incidence.

The patient has two sons and one daughter. Notably, one of her sons was diagnosed with SRUS before her diagnosis and underwent partial rectal resection. The other son was healthy. Additionally, she and her son with SRUS like to eat mixed and coarse grains, and they have high-fiber eating habits and a sedentary lifestyle. Moreover, they are accustomed to squatting for a long time to defecate. Furthermore, they were healthy before the SRUS incidence, but are prone to anxious behaviors in life.

A physical examination upon admission revealed no obvious abnormality in both patients.

Laboratory tests of the female patient revealed high triglyceride (2.11 mmol/L), while others were all within normal ranges. Further, Epstein-Barr virus, and cytomegalovirus were negative. Blood routine, coagulation function and autoimmune tests were within normal ranges. Additionally, laboratory tests of the male patient upon admission revealed no obvious abnormality.

Her total digestive tract endoscopy results revealed a rectal solitary ulcer (Figure 1A), the indicarmine dyeing demonstrated a clear boundary (Figure 1B), and pathological results indicated the fibrous tissue hyperplasia in the lamina propria layer as well as glands destruction (Figure 1D). Ultrasonic endoscopy revealed clearly demarcated mucosal layers, missing ulcerative mucosa and submucosa layers, and intact and thickened muscularis propria (Figure 1C). Moreover, the intestinal computed tomography enhancement revealed segmental rectal wall thickening (Figure 1E). The anorectal function test demonstrated a low resting pressure of the anal canal and normal contractile response and anorectal inhibition reflex but with increased anorectal sensitivity. Further, a colonoscopy of the male patient showed that the mucosa of his rectal anastomosis was smooth without any erosion or ulcer (Supplementary Figure 1).

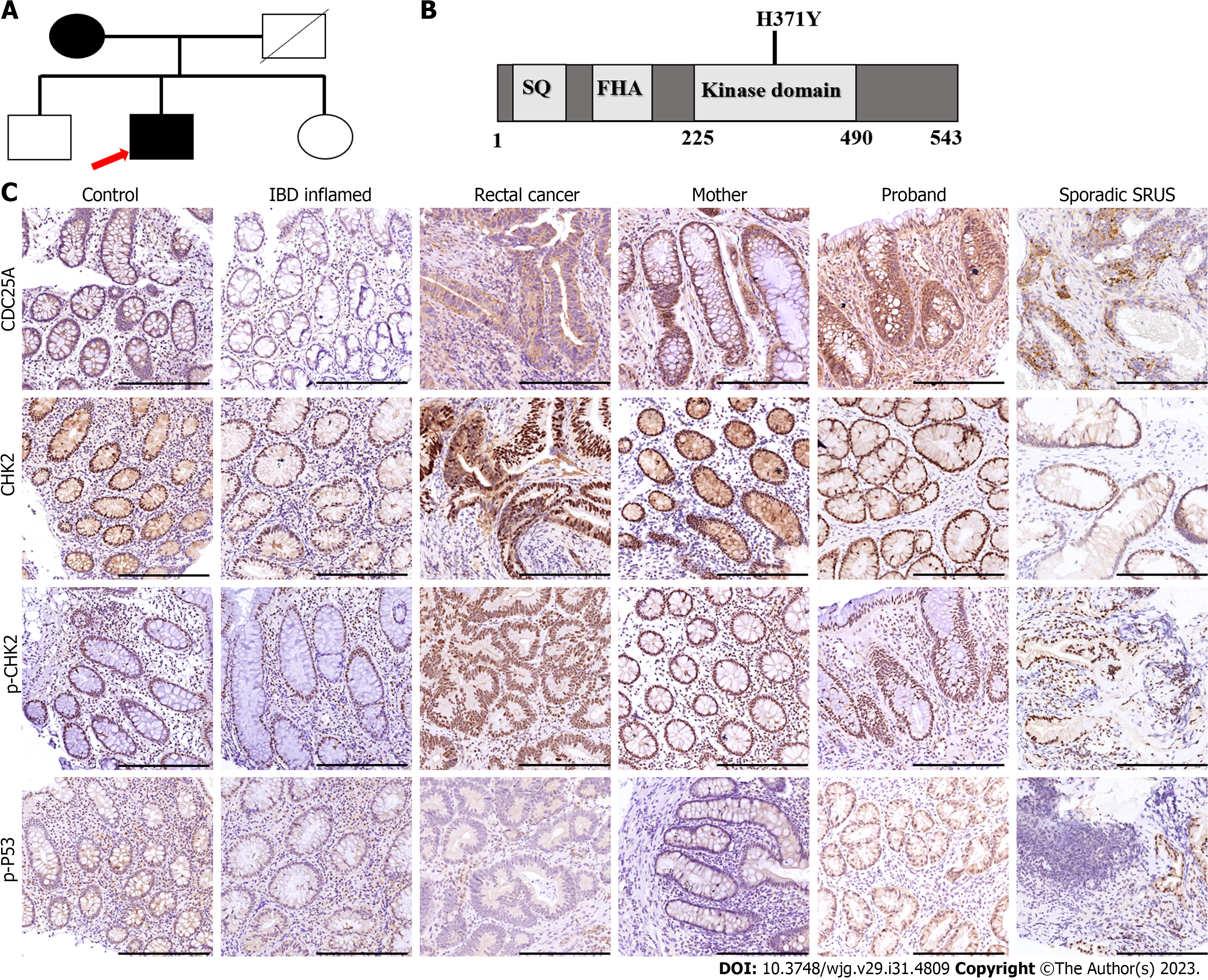

Whereas their complicate family history and next-generation sequencing of heritage whole exome sequencing was then conducted with their consent. The results (Figure 2) exhibited a CHEK2 gene (c.1111C>T, p.His371Tyr) missense mutation in the patient and her son with SRUS, but not in the other son and the daughter. The CHEK2 p.H371Y mutation was reported as a kind of pathologic mutation[4]. Then we conduct the immunohistochemical staining (IHC) to analyze the expression and function of CHEK2 (Antibody: CHEK2, CST#3440, 1:1600; p-CHEK2, CST#82263, 1:500; CDC25A, CST#3652, 1:100; p-P53, CST#9287, 1:100), which revealed a normal CHEK2 protein level but an impaired downstream gene protein level. As shown in Figure 2, CHEK2 protein levels and autophosphorylation CHEK2 protein levels showed no significant difference among the healthy control, inflammatory bowel diseases, rectal cancer and SRUS groups (including familial and sporadic cases). In contrast, the downstream gene of CHEK2, such as CDC25A and p-P53 (Ser 20), exhibit differential expression among these groups. CDC25A and p-p53 protein expression levels were the highest and the lowest in the SRUS group, while the differences between the SRUS and rectal cancer groups do not reach significance.

The SRUS groups contain familial patients in our case and non-familial cases (sporadic cases). The IHC results revealed that the CHEK2 mutation did not affect the expression of CHEK2 protein whether in familial SRUS cases or sporadic SRUS cases, but it would affect CHEK2 functions to different degrees. CDC25A expression level variations are more significant in familial SRUS cases, while p-p53 expression level changes are more pronounced in sporadic SRUS cases.

Both patients with a mother-son relationship were diagnosed with SRUS based on the above-mentioned results.

SRUS treatment should be comprehensive and aimed at restoring the patient’s normal bowel pattern, including behavior modification, medication, biofeedback, and surgery. Initially, we guided patient’s lifestyles and eating habits and advised them to change their sedentary habits and appropriately reduce the amount of dietary fiber in their food. Simultaneously, we guided them to develop good defecation habits, avoid forceful defecation, set defecation time and body position, and artificially limit defecation frequency. Then, we provide psychological care to patients and encourage them to appropriately participate in social activities to vent their bad emotions. Concurrently, biofeedback, which can limit the change of toilet frequency in patients with frequent bowel movements, was recommended as an effective treatment. Biofeedback training can help resolve symptoms, especially in patients who remain symptomatic postoperatively. Finally, we advise patients to use thalidomide and mesalazine for rapid improvement of inflammation, considering the long medical history of the patient, especially frequent diarrhea in the male patients. Mesalazine is a commonly used drug for SRUS and thalidomide is used for anti-inflammation and its side effects of constipation and improved sleeping happen to help patients relieve diarrhea and help them sleep.

Changes in eating and living habits need to be maintained for a long time. Patients are advised to undergo re-examination 3 mo after drug treatment and biofeedback adjuvant therapy. A significant improvement can be maintained for a long time under the condition of monitoring drug side effects. Additionally, the medication regimen was adjusted following the patient’s symptoms during the follow-up. Patients’ symptoms were significantly improved under the comprehensive treatment. The reexamination results after 3 mo indicated a significantly relieved mucosa (Figure 1F). Patients remain under regular follow-up and treatment annually.

Previous studies have reported the relevance of rectal mucosal prolapse, ischemia, or injury to SRUS pathogens. These main SRUS features include the following clinical manifestations: defecation difficulty with mucous blood stools and lower abdominal pain, normal general physical examination condition, colonoscopy revealing an isolated rectal ulcer, ultrasound colonoscopy showing proliferative mucosal lesions, pathological results demonstrating mucosal myometrium hyperplasia and fibrosis, dynamic examination indicating abnormal rectal and pelvic floor dynamics, normal blood and inflammatory markers, and negative tumor markers[5].

SRUS has no specific clinical manifestation, thus it is frequently misdiagnosed because its clinical diagnosis mainly depends on endoscopy and histopathology. Current SRUS treatment includes medical, surgical treatment, and biofeedback therapy. Drug therapy aims to inhibit inflammatory response and proliferation. Literature reports revealed a similar treatment plan to ulcerative colitis (UC), which can be used orally with mesalazine and locally with rectal administration. This disease has a long treatment period, causing a non-exact therapeutic effect, although biofeedback therapy aims to harmonize and improve pelvic floor muscle function. However, biofeedback therapy may be effective for patients with pelvic floor dysfunction[6]. Surgical treatment is an alternative option, but it is only effective for some patients and has a risk of recurrence postoperatively. Hence, surgical treatment should not be the first therapeutic choice.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of two patients with SRUS in a mother-son relationship. Thus, this is the first study to indicate a possible genetic background for SRUS. The mother in our cases had a very late onset although SRUS was rarely reported in patients over 60 years old. Meanwhile, the symptoms of both patients have commonalities and differences. Her ulcer and symptom significantly improved after medication, while her young son’s symptoms did not improve much even with surgery, although a follow-up colonoscopy revealed no further rectal mucosa damage and anastomosis. Concurrently, long-term diarrhea caused psychologically abnormalities, specifically anxiety, in the young male thereby aggravating diarrhea symptoms. Therefore, surgery may be not available for all patients. Most importantly, the psychological symptoms of the disease should also be considered an important treatment scheme aspect.

Genetic data on SRUS is limited. Genes, heritage data, and features need to be explored for a better understanding of the SRUS pathogen and mechanism. Our cases demonstrated that CHEK2 p.H371Y mutation may be relevant to SRUS development and prognosis. CHEK2 is a cell cycle checkpoint regulator, and it plays an essential role in DNA damage repair. Phosphorylation of p53/TP53 at “Ser-20” by CHEK2 is required for the accumulation of active TP53. When activated, the encoded CHEK2 is known to inhibit CDC25A through phosphorylation of CDC25A and cause its degradation[7]. The CHEK2 p.H371Y mutation was reported as a pathogenic mutation causing decreased kinase activity because p.H371Y is located within the activation region of the CHEK2 protein kinase domain. Here, we performed a series of clinical specimens, which revealed no changes in the CHEK2 expression level while the downstream gene expression was significantly modified, exhibiting an impaired CHEK2 protein function. Both familial and sporadic SRUS cases showed weakened function in CHEK2 protein, and familial SRUS cases are mainly characterized by changes in CDC25A of CHEK2 downstream, while sporadic SRUS cases are mainly characterized by variations in p-p53 of CHEK2 downstream. We speculate similarities and differences in the pathogenesis and prognosis between familial SRUS and non-familial SRUS.

Previous studies have revealed that CHEK2 is associated with inflammation and functions through the kinase mechanism to down-regulate the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) pathway in macrophages to alleviate Staphylococcus aureus-induced pneumonia in mice. Additionally, phospho-CHEK2 was associated with high macrophage infiltration in UC[8]. Moreover, SRUS is a manifestation of inflammation and CHEK2 mutation may contribute to the development of SRUS via effects on inflammatory pathways, such as the NF-κB pathway[9]. Furthermore, the CHEK2 gene is associated with rectal cancer and inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD). SRUS is closely correlated with rectal cancer and IBD, thus it is difficult to differentiate the diagnosis between SRUS from IBD, especially through UC[10]. Rectal cancer is the most important aspect of SRUS prognostic follow-up, but whether the CHEK2 gene is a pathological gene causing SRUS or a gene for assessing the SRUS prognosis or a potential cause of rectal cancer remains uncertain, as well as the exact role of CHEK2 p.H371Y mutation in familial SRUS.

Limitations related to a small-cohort study and the patient heterogeneity exist. The following possible drawbacks may occur in our study. Firstly, this is a single case report and a retrospective study, and the role of CHEK2 mutation in SRUS pathogenesis needs further investigation. Secondly, this study did not involve the detailed mechanism of CHEK2 mutation causing SRUS. Therefore, subsequent verification of large samples and more detailed experimental verification should be prepared.

In summary, this is the first study to report two patients with SRUS in a mother-son relationship with an inherited CHEK2 p.H371Y mutation, which provides insights that SRUS may serve as a genetic susceptibility disease, and CHEK2 p.H371Y mutation may play a crucial role in the development and prognosis of SRUS.

The authors thank Wei Zhang, BS, from the Department of Pathology in The Third Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University for the histology slides and for providing helpful advice.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Choi YS, South Korea; Zamani M, Iran S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Cai YX

| 1. | Rutter KR. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome. Proc Royal Soc Med. 1975;68:22-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Gouriou C, Siproudhis L, Chambaz M, Ropert A, Wallenhorst T, Merlini-l'Héritier A, Carlo A, Bouguen G, Brochard C. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome in 102 patients: Do different phenotypes make sense? Dig Liver Dis. 2021;53:190-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Felt-Bersma RJF. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2021;37:59-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bartek J, Falck J, Lukas J. CHK2 kinase--a busy messenger. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:877-886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 280] [Cited by in RCA: 298] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Abusharifah O, Bokhary RY, Mosli MH, Saadah OI. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome in children and adolescents: a descriptive clinicopathologic study. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2021;14:399-407. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Forootan M, Shekarchizadeh M, Farmanara H, Esfahani ARS, Esfahani MS. Biofeedback efficacy to improve clinical symptoms and endoscopic signs of solitary rectal ulcer syndrome. Eur J Transl Myol. 2018;28:7327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Xu X, Tsvetkov LM, Stern DF. Chk2 activation and phosphorylation-dependent oligomerization. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:4419-4432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Xie F, Chen R, Zhao J, Xu C, Zan C, Yue B, Tian W, Yi W. Cell cycle kinase CHEK2 in macrophages alleviates the inflammatory response to Staphylococcus aureus-induced pneumonia. Exp Lung Res. 2022;48:53-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sohn JJ, Schetter AJ, Yfantis HG, Ridnour LA, Horikawa I, Khan MA, Robles AI, Hussain SP, Goto A, Bowman ED, Hofseth LJ, Bartkova J, Bartek J, Wogan GN, Wink DA, Harris CC. Macrophages, nitric oxide and microRNAs are associated with DNA damage response pathway and senescence in inflammatory bowel disease. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Abid S, Khawaja A, Bhimani SA, Ahmad Z, Hamid S, Jafri W. The clinical, endoscopic and histological spectrum of the solitary rectal ulcer syndrome: a single-center experience of 116 cases. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |