Published online Aug 14, 2023. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v29.i30.4642

Peer-review started: February 9, 2023

First decision: May 16, 2023

Revised: May 26, 2023

Accepted: July 17, 2023

Article in press: July 17, 2023

Published online: August 14, 2023

Processing time: 182 Days and 9.9 Hours

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a disease featuring acute inflammation of the pancreas and histological destruction of acinar cells. Approximately 20% of AP patients progress to moderately severe or severe pancreatitis, with a case fatality rate of up to 30%. However, a single indicator that can serve as the gold standard for prognostic prediction has not been discovered. Therefore, gaining deeper insights into the underlying mechanism of AP progression and the evolution of the disease and exploring effective biomarkers are important for early diagnosis, progression evaluation, and precise treatment of AP.

To determine the regulatory mechanisms of tRNA-derived fragments (tRFs) in AP based on small RNA sequencing and experiments.

Small RNA sequencing and functional enrichment analyses were performed to identify key tRFs and the potential mechanisms in AP. Reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) was conducted to determine tRF expression. AP cell and mouse models were created to investigate the role of tRF36 in AP progression. Lipase, amylase, and cytokine levels were assayed to examine AP progression. Ferritin expression, reactive oxygen species, malondialdehyde, and ferric ion levels were assayed to evaluate cellular ferroptosis. RNA pull down assays and methylated RNA immunoprecipitation were performed to explore the molecular mechanisms.

RT-qPCR results showed that tRF36 was significantly upregulated in the serum of AP patients, compared to healthy controls. Functional enrichment analysis indicated that target genes of tRF36 were involved in ferroptosis-related pathways, including the Hippo signaling pathway and ion transport. Moreover, the occurrence of pancreatic cell ferroptosis was detected in AP cells and mouse models. The results of interference experiments and AP cell models suggested that tRF-36 could promote AP progression through the regulation of ferroptosis. Furthermore, ferroptosis gene microarray, database prediction, and immunoprecipitation suggested that tRF-36 accelerated the progression of AP by recruiting insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA binding protein 3 (IGF2BP3) to the p53 mRNA m6A modification site by binding to IGF2BP3, which enhanced p53 mRNA stability and promoted the ferroptosis of pancreatic follicle cells.

In conclusion, regulation of nuclear pre-mRNA domain-containing protein 1B promoted AP development by regulating the ferroptosis of pancreatic cells, thereby acting as a prospective therapeutic target for AP. In addition, this study provided a basis for understanding the regulatory mechanisms of tRFs in AP.

Core Tip: Based on reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction and bioinformatic analysis of small RNA sequencing data extracted from three patients and three healthy controls, and validated by 20 acute pancreatitis (AP) patients and 20 healthy controls, we found that tRNA-derived fragments 36 (tRF36) was significantly upregulated in AP. Further

- Citation: Fan XR, Huang Y, Su Y, Chen SJ, Zhang YL, Huang WK, Wang H. Exploring the regulatory mechanism of tRNA-derived fragments 36 in acute pancreatitis based on small RNA sequencing and experiments. World J Gastroenterol 2023; 29(30): 4642-4656

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v29/i30/4642.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v29.i30.4642

As a common acute and critical condition of the digestive system, acute pancreatitis (AP) refers to local inflammation of the pancreas and even organ dysfunction due to self-digestion of the pancreas and surrounding organs after abnormal activation of pancreatic enzymes. The prevalence of AP is rising annually, with a global incidence of 4.9-73.4 per 100000 person-years[1]. Most patients display mild symptoms, recover gradually with treatment and have a good prognosis, however, approximately 20% of patients progress to moderately severe or severe pancreatitis, with a case fatality rate (CFR) of up to 30%[2]. Organ failure and pancreatic infection necrosis are believed to be the common causes of mortality in AP patients, and prompt and effective early intervention can improve the prognosis[3]. Accordingly, the prognosis of AP must be predicted at onset. However, a single indicator that can serve as the gold standard for prognostic prediction has not been discovered. Therefore, gaining deeper insights into the underlying mechanism of AP progression and the evolution of the disease and exploring effective biomarkers are important for early diagnosis, progression evaluation, and precise treatment of AP.

Programmed death of pancreatic acinar cells is the major pathophysiological change in the early stages of AP, with the mode of pancreatic acinar cell death playing a vital role in determining AP advancement and prognosis[4,5]. Ferroptosis is a new type of cell death characterized by intracellular iron-dependent lipid peroxidation. In recent years, excessive cellular ferroptosis has been demonstrated to exert a vital role in the pathogenesis of aseptic inflammatory conditions, such as ischemia-reperfusion injury and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis[6]. According to recent studies using a mouse model of AP with knockout of pancreatic tissue glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), the ferroptosis of pancreatic acinar cells exacerbates pancreatic tissue injury, leading to significantly elevated levels of relevant biomarkers and accelerated AP progression[7,8]. The core proteoglycan released from the cells that have undergone ferroptosis can trigger immune responses and the production of proinflammatory cytokines, thereby exacerbating pancreatic acinar cell death and leading to further exacerbation of AP[9]. As shown above, ferroptosis of pancreatic acinar cells promotes the aggravation of AP; however, the molecular mechanism regulating the ferroptosis of pancreatic acinar cells remains unclear.

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) are gaining increasing interest for AP diagnosis and treatment and are expected to be potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets[10]. tRNA-derived fragments (tRFs) have recently been identified as ncRNAs produced from mature tRNAs or tRNA precursors through a specific mechanism of action[11]. tRFs are widespread in various organisms and are extremely conserved, structurally robust, and tissue specific, participating in different physiological and pathological processes[12]. A sequencing study revealed that several tRFs were abnormally expressed in AP cell models, among which tRF3-Thr-AGT affected AP progression by regulating trypsinogen activation in pancreatic acini[13]. Subsequently, another study revealed that tRF3-Thr-AGT expression was significantly downregulated in the pancreatic tissues of an AP cell model and an AP animal model, while overexpression of tRF3-Thr-AGT inhibited NACHT, LRR, and PYD domains-containing protein 3 (NLRP3)-mediated pyroptosis and the inflammatory responses of pancreatic acinar cells and alleviated AP progression[14]. Accordingly, tRF3-Thr-AGT may be deployed as a biomarker for AP diagnosis and treatment[14].

In this study, serum RNA extraction for AP patients and healthy controls and small RNA sequencing were performed. Thereafter, candidate tRFs were identified using bioinformatics and validated using reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR). The most significantly differentially expressed tRF36 was selected for subsequent investigation. An AP cell model and an AP mouse model were constructed to probe the role and mechanism of tRF36 in regulating ferroptosis and promoting AP progression and to identify the downstream effector pathways and targets. tRF36 was found to promote AP development and progression by regulating P53 expression and ferroptosis by binding to insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA binding protein 3 (IGF2BP3). This finding provides a theoretical foundation for gaining further insights into the pathogenesis of AP and identifying new potential therapeutic targets.

Serum was collected from three patients with AP and three healthy controls. Total RNA was retrieved utilizing the TRizol method, and libraries were constructed utilizing the Multiplex Small RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB, United States). The procedure included: (1) 3’ splice ligation; (2) Reverse primer hybridization; (3) 5’ splice ligation; (4) One-strand cDNA synthesis; (5) PCR enrichment; and (6) 8% sodium dodecyl-sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis fragment sorting (SDS-PAGE). Thereafter, 2 × 150 bp sequencing was performed on an Illumina platform (Yingbiotech, Shanghai, China). This study was approved by Medical Ethics Committee of Yan’an Hospital Affiliated To Kunming Medical University (Approval No. 2022-024-01).

The overall quality of the sequencing data was evaluated via Fast-QC software (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/). For tRFs, sequences that did not match the miRBase (12-23 bp, 34-43 bp) and piRNAcluster (24-33 bp) were compared to rRNA. After we filtered out sequences that could be matched to rRNA, sequences that could be matched to the GtRNA database were matched to the tRFdb and tRFMINTbase databases to obtain tRF expression profiles. Finally, differential expression analysis of tRFs was performed using the DESeq2.0 algorithm (P value < 0.05 and |log2 fold change| > 1).

The target genes for the tRFs were mined via miranda (score > 150, energy < -20) and RNAhybrid (energy < -25), and the ultimate target genes were recognized by intersecting the two algorithms. For Gene Ontology (GO) analysis, the significance level of each GO was calculated depending on the GO database (http://www.geneontology.org/) and Fisher’s test. The target genes were also annotated with pathways depending on the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/) to obtain all pathways involving the genes. The significance level (P value) of each pathway was calculated using Fisher’s test and pathways with P value < 0.05 were deemed significantly enriched.

We collected serum from 20 patients with AP and 20 healthy controls. Total RNA was retrieved utilizing TRizol (Invitrogen), and reverse transcribed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo, K1622). qPCR was carried out using 2 × Master Mix (Roche). The following thermocycling program was employed for qPCR: 1 cycle at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles at 95 °C for 15 s, and 60 °C for 60 s. The relative expression level was normalized to that of the endogenous control U6 and calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method[15].

Cerulein is a cholecystokinin analogue that provokes the secretion of digestive enzymes in the pancreas of humans and rodents[16]. Cerulein-induced pancreatitis is one of the best featured animal models of pancreatitis, which was first described in 1977 and is highly reproducible and economical[16-18]. Briefly, 10 nM cerulein (MCE, HY-A0190) was administered to the mouse pancreatic acinar carcinoma cell line MPC-83 (Shanghai Bei Nuo Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China) to develop an AP cell model. Male BALB/C mice (age, 6-8 wk; weight 25 ± 3 g; Beijing SiPeiFu Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China) were intraperitoneally administered cerulein 10 times at 1-h intervals to establish the AP mouse model. This study was approved by Animal Ethics and Welfare Committee of Kunming Yan’an hospital (Approval No. 2022013) in accordance with internationally accepted principles for the use of laboratory animals.

According to the manufacturer’s protocols, Lipofectamine™ 2000 Transfection reagent (Invitrogen, United States) was utilized to transfect the tRF-36 inhibitor into MPC-83 cells to knock down the expression of tRF-36. qRT-PCR was conducted to determine the knockdown efficiency of tRF-36.

The viability of cells was determined via Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assays (Beyotime, China). Then, we seeded 103 cells into a 96-well plate and added 10 μL of CCK-8 per well. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) microplate reader (Infinite M1000, Tecan) after 1 h of incubation.

The levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-6, IL-1β, mouse amylase (AMS), and mouse lipase (R&D Systems, MN, United States) were determined using ELISA kits and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Infinite M1000, Tecan).

Cell death was assessed using the TUNEL Kit (Sangon Biotech), as described by the manufacturer. A fluorescent microscope (Nikon, Japan) was utilized to observe the specimens.

The oxidative-sensitive fluorescent probe DCFH-DA in the reactive oxygen species (ROS) Assay Kit (Beyotime, China) was utilized to assess the generation of intracellular ROS. A laser confocal microscope (Nikon, Japan) was utilized to observe the green fluorescence intensity. Malondialdehyde (MDA) is a metabolite of lipid oxidation and is widely used as an indicator of lipid oxidation. An MDA detection kit (Beyotime, S0131) was used to measure the MDA level in cells or tissues according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

A ferric ion colorimetric assay kit (Pulley’s, #E1042) was used to measure ferric ion levels in mouse pancreatic tissue, according to the manufacturer’s manuals.

Cells were lysed using RIPA lysis buffer, homogenized, and centrifuged. Thereafter, the supernatant was collected. Then, the protein concentration was measured using the bicinchoninic acid assay. The proteins were separated via SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. After that, the membranes were incubated at 4 °C overnight with specific primary antibodies against p53 (Proteintech, 60004-1-Lg) and ferritin (Abcam, ab75973) after blocking with 5% nonfat milk. The membrane was then incubated with secondary antibody for 60 min. After the membrane was washed with TBST solution, it was analyzed using the chemiluminescence method. The relative quantification was performed using scanning software (ImageJ grayscale).

The mouse lung and pancreatic tissues were washed with phosphate buffered saline and fixed for 24 h in 4% paraformaldehyde fixative solution. Thereafter, conventional paraffin embedding was conducted, and tissue sections (4 μm) were prepared for hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining. Finally, the histopathological morphology of the sections was observed under a microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

The tissue sections were dewaxed, rehydrated with xylene, and washed with an alcohol gradient. After soaking and washing with distilled water, H2O2 was used to destroy endogenous peroxidase activity. After incubation with anti-ferritin antibody (Abcam, ab75973), the sections were exposed to secondary antibodies. Instillation with diaminobenzidine for 5 min was then performed. Thereafter, the sections were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated with ethanol, and clarified with xylene. Observation and image capture were performed using a microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

The tRF36 probe labeled by biotin was generated, and a Magnetic RNA-Protein Pull-Down Kit [Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China)] was utilized to implement the RNA pull-down assay depending on the manufacturer’s instructions. First, the tRF36 probe or control probe was incubated with streptavidin magnetic beads for 30 min at room temperature. Thereafter, the cell lysates were incubated with probe-bead complexes for 1 h at 4 °C to enable binding of the proteins to RNAs. The RNA-protein complexes were washed and eluted from beads via incubation at 37 °C for 30 min with agitation. The eluted proteins were finally analyzed via silver staining. The differential protein bands of immunoglobulin G and tRF36-IP lanes were cut and sent to the mass spectrometry platform for protein profiling.

The methylated RNA immunoprecipitation (MeRIP) experiments were completed via the riboMeRIPTM m6A Transcriptome Profiling Kit (Merck Millipore) to capture the RNA modified by m6A. Briefly, the total RNA of AP model cells and control cells was extracted by TRizol (Invitrogen). After fragmentation, RNA was incubated with the magnetic bead-m6A antibody complex for immunoprecipitation. MeRIPed p53 was then analyzed using qRT-PCR.

The experimental data were compared via student’s t test to determine the group difference. If not specified above, a P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Based on quality control and preprocessing of the raw small RNA sequencing data for three serum samples from three AP patients and three control samples, we found that the sequencing quality met the criteria for subsequent analysis (Supplementary Figure 1). By RNA mapping based on the BWA algorithm, tRF expression data were extracted. A total of 116 upregulated tRFs and 95 downregulated tRFs in AP were screened via differential expression analysis (Figures 1A and B, Supplementary Table 1). According to functional enrichment analysis, many biological processes and pathways, including the Wnt signaling pathway, Hippo signaling pathway, and ion transport, were associated with the target genes of these differentially expressed tRFs (DE-tRFs) (Supplementary Figure 2).

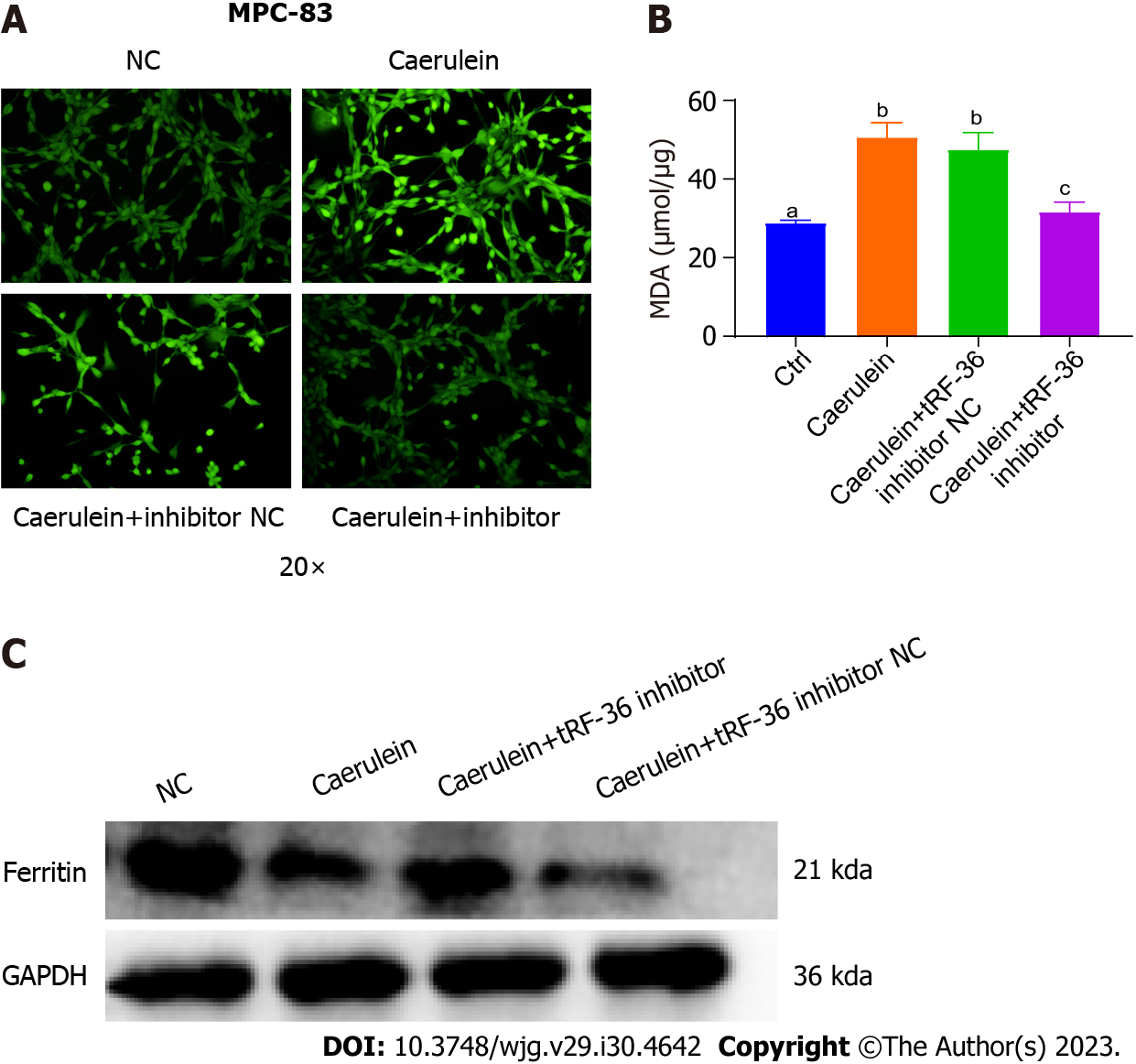

Due to the uncertainty of high-throughput sequencing, we collected serum from 20 AP patients and 20 healthy controls and verified the five most significant DE-tRFs using RT-qPCR (Figure 1C). As shown in Figure 1C, tRF36 was downregulated in the serum of AP patients, and its differential expression was the most significant (P < 0.05, Figure 1C). This finding implied that tRF36 played an important role in AP progression. To test our hypothesis, we generated an AP cell model using the MCP-83 cell line. Figure 2A revealed that the expression of tRF-36 was significantly reduced after the use of inhibitor. It is well known that AMS and lipase have diagnostic value for AP[19], and the inflammatory response is associated with AP-induced injury[20]. Therefore, we measured the expression of AMS and lipase as well as inflammatory factors to determine the feasibility of the model. After MCP-83 cells were treated with cerulein, the levels of AMS and lipase and the inflammatory factors TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β in the cell supernatant increased significantly, indicating successful establishment of the AP cell model (Figures 2B-F). After knockdown of tRF36, these markers were further assayed in the cell supernatants. Based on the results, the levels of AMS and lipase and the inflammatory factors TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β in the cell supernatant were significantly reduced after knockdown of tRF36 (Figures 2B-F). Cell viability and cell death were measured by CCK-8 and TUNEL assays, respectively. Knockdown of tRF36 was found to significantly increase cell viability, and significantly reduce cell death (Figures 2G and H). These results suggest that tRF36 contributes to AP progression by promoting cell death.

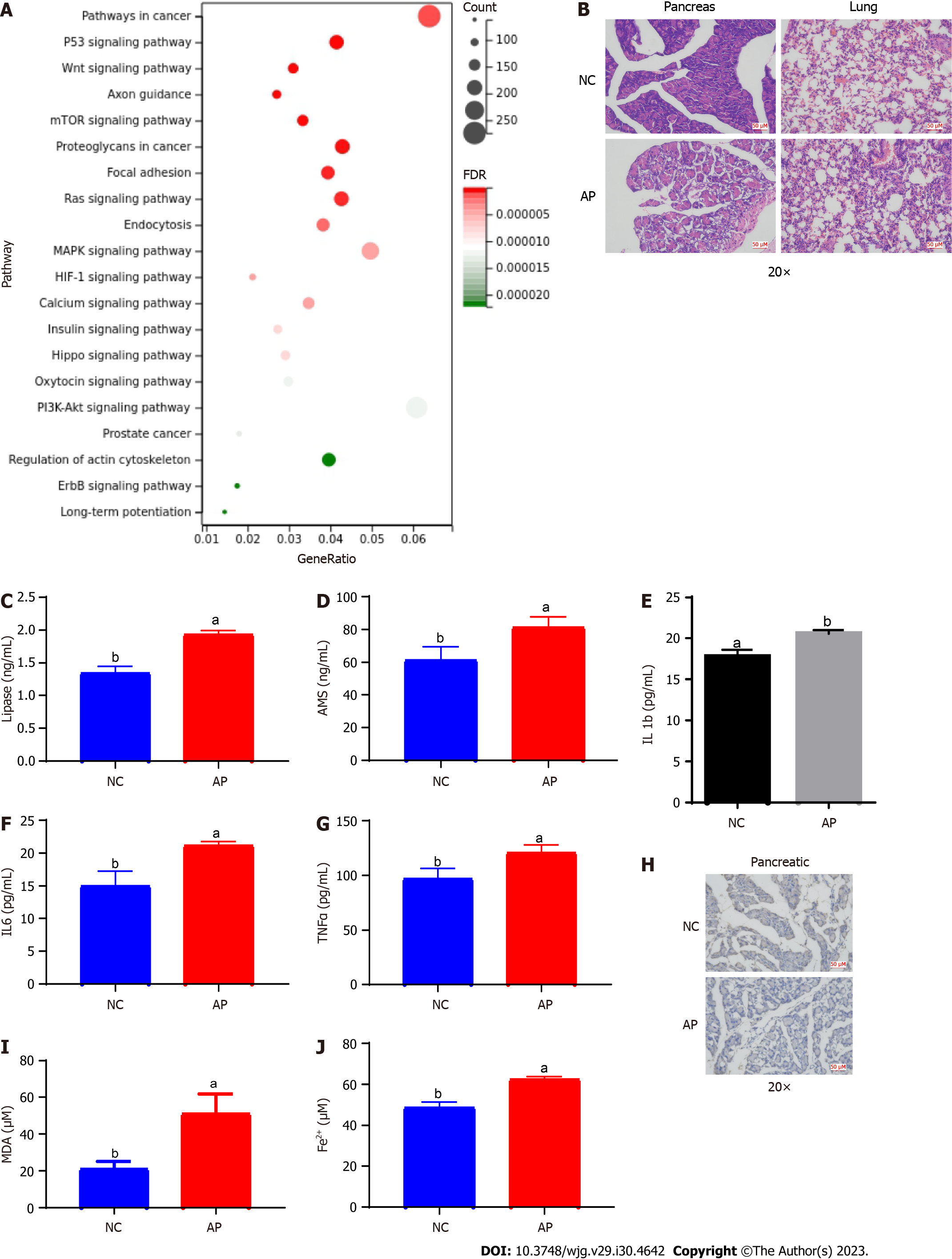

We proceeded to conduct functional enrichment analysis of the target genes of tRF36 (KEGG pathway). The target genes of tRF36 were found to be involved in ferroptosis-related pathways, namely, the P53 signaling pathway and mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway (Figure 3A). To confirm the presence of ferroptosis in AP progression, we constructed an AP mouse model. Based on HE staining of lung and pancreatic tissues, significant changes were observed in pancreatic tissue cell morphology (Figure 3B). Furthermore, the serum levels of lipase and AMS in the AP model mice were significantly higher than those in the controls (Figures 3C and D). The serum levels of the inflammatory factors TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β were also significantly increased in the AP model mice (Figures 3E-G). Therefore, the AP mouse model was successfully established. Subsequently, the levels of ferritin expression, ferric ions, and the lipid oxidation metabolite MDA were examined in pancreatic tissue. The expression of ferritin in the pancreatic tissues of the AP model mice was significantly reduced (Figure 3H). Correspondingly, the levels of ferric ion concentration and MDA were significantly increased (Figures 3I and J). These results highlighted the presence of cell ferroptosis in AP.

Based on the above results, we hypothesized that tRF36 may promote AP progression by regulating cell ferroptosis. Hence, we examined the ROS levels in AP model cells. The ROS levels of cells in the model group were found to be significantly higher than those in the control group (Figure 4A). Similar results were obtained using the AP cell model (e.g., decreased ferritin expression and increased MDA levels) compared to control cells, which were similar to those of the mouse model (Figures 4B and C), suggesting the presence of cell ferroptosis in the AP model. After knockdown of tRF36 in MCP-83 cells, a significant decrease in ROS levels and MDA and a significant increase in ferritin expression levels were found in cells (Figures 4A-C). Therefore, we concluded that tRF36 could promote AP progression through the regulation of ferroptosis.

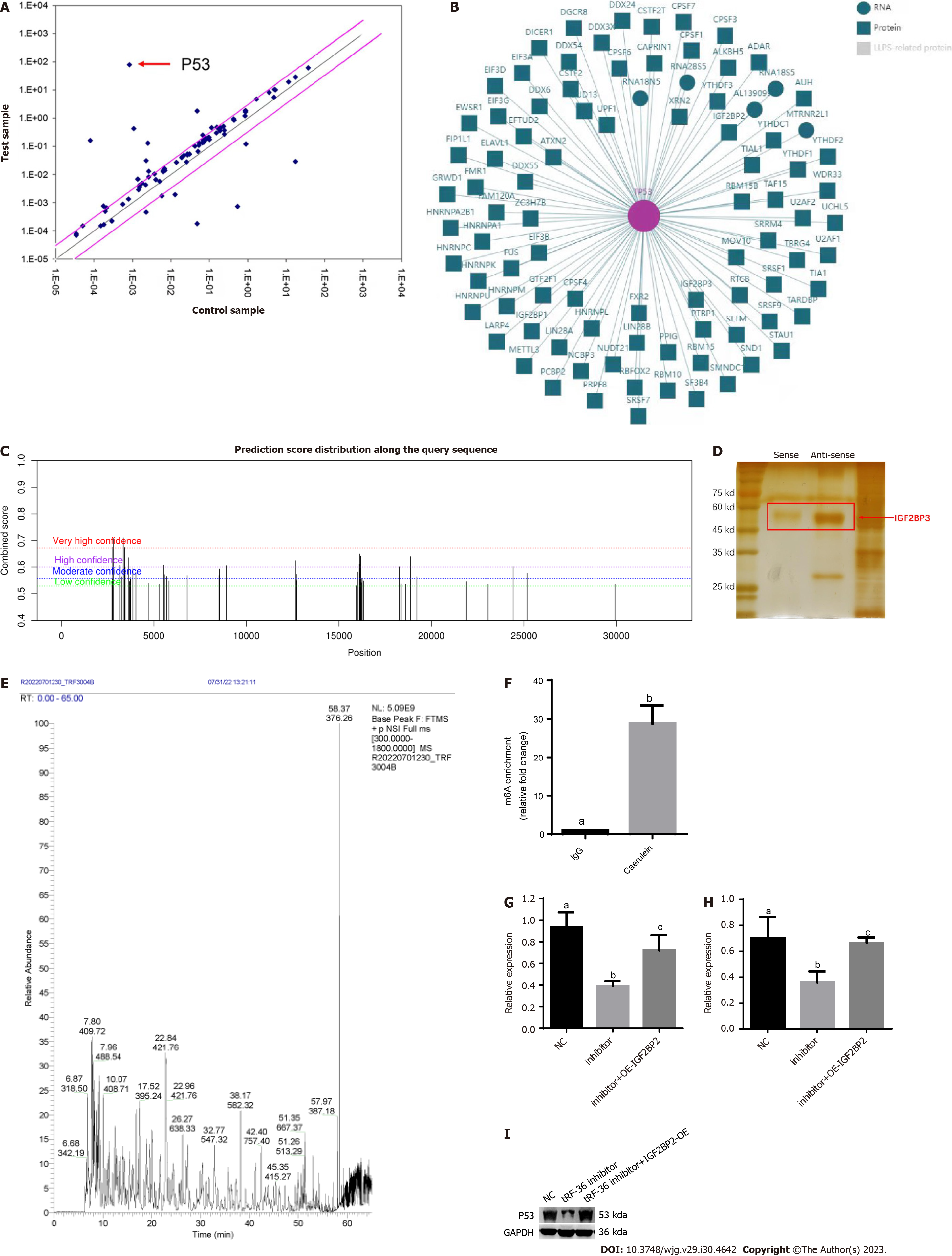

To further probe the molecular mechanisms underlying the regulation of ferroptosis by tRF36, we utilized a ferroptosis gene microarray to determine the differentially expressed ferroptosis genes after tRF36 knockdown. The gene expression of p53 was the most significantly downregulated of the genes (Figure 5A). Database analysis revealed that p53 mRNA interacts with several m6A proteins, including METTL3, ALKBH5, IGF2BP3, and others (Figure 5B). The SRAMP database (http://www.cuilab.cn/sramp) predicted that p53 mRNA has m6A modification sites with a very high probability of modification (Figure 5C). Therefore, we searched for proteins interacting with tRF-36 using an RNA pull down assay and mass spectrometry, which revealed that tRF-36 interacts with the m6A methylation regulator IGF2BP3 (Figures 5D and E, Supplementary Table 2). IGF2BP3 is a unique m6A reader protein that promotes stable mRNA expression and prevents mRNA degradation[21]. MeRIP-qPCR results revealed that the level of m6A modification of p53 was elevated in the AP cell model (Figure 5F). Western blot and qPCR analyses revealed that the knockdown of tRF36 in the AP cell model resulted in a significant reduction in p53 expression (Figures 5G and H). Interestingly, p53 expression was significantly restored after the overexpression of IGF2BP3 in cells with tRF36 knockdown (Figures 5G and H). Therefore, we speculated that tRF36 accelerated the progression of AP by recruiting IGF2BP3 to the p53 mRNA m6A modification site through binding to IGF2BP3, which enhanced p53 mRNA stability and promoted the ferroptosis of pancreatic follicle cells (Figure 6). The p53 expression level after the knockdown of tRF36 was determined by western blot qPCR.

The incidence of AP is increasing annually, with a global incidence of 4.9-73.4 per 100000 person-years[1]. Approximately 20% of AP cases will progress to moderate or severe pancreatitis, with a CFR of up to 30%[2]. The pathogenesis of AP is complex, and no effective clinical treatment has been developed to date. Therefore, gaining deeper insights into the underlying mechanism of AP progression and exploring effective biomarkers are important for AP diagnosis and treatment[9]. In this study, tRF36 was discovered to play an important role in AP progression; thus, its regulatory mechanism was explored.

Sequencing and bioinformatics analyses were performed using the small RNAs extracted from the serum samples of AP patients and healthy controls. Validation of tRF36, the most significantly expressed molecule, was performed using qPCR. The downstream target genes of tRF36 were then predicted and analyzed to explore their potential biological functions.

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis revealed that the target genes of tRF36 were mainly enriched in the ferroptosis-related p53 and mTOR signaling pathways. Numerous studies have confirmed that the p53 signaling pathway can regulate ferroptosis. For example, Chen et al[22] found that iPLA2 β-mediated lipid detoxification is vital for inhibiting the ROS-induced ferroptosis of cancer cells. Chu et al[23] found an ALOX12-mediated, ACSL4-independent ferroptosis pathway that is vital for p53-dependent tumor suppression. Lei et al[24] found that radiotherapy (RT)-mediated p53 activation antagonizes RT-induced SLC7A11 expression and inhibits glutathione synthesis, thereby promoting RT-induced lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis. Li et al[25] found that ferroptosis contributes to acute lung injury induced by intestinal ischemia/reperfusion and that iASPP treatment partially inhibits ferroptosis via nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2). Jiang et al[26] found that p53 inhibits cystine uptake and sensitizes cells to ferroptosis by suppressing SLC7A11 expression.

Numerous studies have shown that the mTOR signaling pathway regulates ferroptosis. For example, Conlon et al[27] found that acute amino acid deprivation-induced proliferative arrest correlates with protection from ferroptosis in a manner independent of mTOR inhibition and GCN2/ATF4 pathway activation. Sun et al[28] not only supported the concept that ferroptosis is autophagy-dependent cell death but also suggested that the combined application of ferroptosis inducers and mTOR inhibitors is a promising approach to improve bladder cancer treatment options. Hsieh et al[29] found that ZVI-NP selectively triggered the ferroptosis of cancer cells by inhibiting the Nrf2-mediated cytoprotective program, which was attributed to ZVI-NP-induced disruption of AMPK/mTOR signaling and activation of the GSK3βSK-TrCP-dependent degradation system.

In recent years, the role of ncRNAs in AP has received increasing attention, and ncRNAs are expected to be a potential biomarker and therapeutic target. Owing to the development of sequencing technology, many AP-associated ncRNAs have been identified, such as long ncRNAs, microRNAs, and tRFs[30,31], suggesting that ncRNA dysregulation plays an important role in the development of AP. For example, Li et al[32] demonstrated that tRNA-derived small RNAs (tsRNAs) can be used as a potential therapeutic biomarker for bile duct cancer. The sequencing results of Yang et al[13] revealed that different tRFs were abnormally expressed in AP cell models, and tRF3-Thr-AGT affected AP progression by regulating trypsinogen activation in pancreatic acini. A later study further showed that tRF3-Thr-AGT expression was significantly downregulated in the pancreatic tissues of an AP cell model and an AP animal model, while overexpression of tRF3-Thr-AGT inhibited the NLRP3-mediated pyroptosis and inflammatory responses of pancreatic acinar cells, thereby alleviating AP progression[14]. However, no existing studies have reported the involvement of tRF36 in regulating the pathogenesis of AP. In the present study, tRF36 expression was upregulated in the serum of AP patients, and knockdown of tRF36 resulted in a significant decrease in AMS and lipase levels in cell supernatants and a reduction in pancreatic acinar cell death. Therefore, tRF36 exacerbates AP by promoting pancreatic acinar cell death and may be a diagnostic biomarker in clinical treatment.

In AP mouse models in which GPX4 was knocked out in pancreatic tissues, the ferroptosis of pancreatic acinar cells exacerbated pancreatic tissue damage, leading to a significant increase in the levels of relevant biomarkers and accelerated progression of AP[7,8]. The core proteoglycan released from cells that have undergone ferroptosis can trigger immune responses and the production of proinflammatory cytokines, thereby exacerbating pancreatic acinar cell death and leading to further exacerbation of AP[9]. In mice and cell models of AP, the expression of ferritin decreased and MDA level increased. Hou et al[33] suggested that ferritin was a major intracellular iron storage protein complex, and its increased expression would limit ferroptosis. On the contrary, there was a low ferritin expression level during ferroptosis. As shown above, ferroptosis of pancreatic acinar cells promotes the aggravation of AP.

In the present study, we constructed an AP cell model in which tRF36 was knocked down in the pancreatic acinar cells. A ferroptosis gene microarray was performed to identify the key genes involved in ferroptosis, among which P53 was demonstrated to exhibit the most significant expression. Database-based prediction revealed that p53 mRNA has an m6A modification site where p53 mRNA interacts with some m6A-reader proteins. Goodarzi et al[34] found that tsRNA can inhibit the stability of multiple proto-oncogene transcripts in breast cancer cells by competitively binding to the RNA-binding protein YBX1. Thus, tRFs can regulate the stability of downstream gene transcripts via RNA-binding proteins. Accordingly, an RNA pulldown assay combined with mass spectrometry was performed in the present study, which revealed that tRF36 interacted with IGF2BP3. Finally, based on gene interference, overexpression, MeRIP-PCR, RNA pulldown assays, western blotting, and rescue assays, IGF2BP3 was confirmed to regulate the ferroptosis of pancreatic acinar cells by regulating P53 expression by enhancing P53 mRNA stability. Taken together, the above findings suggest that the acceleration of AP progression by tRF36 may involve the process of tRF36 recruiting IGF2BP3 to the m6A modification site of P53 mRNA by binding to IGF2BP3, which enhances P53 mRNA stability, ultimately promoting the ferroptosis of pancreatic acinar cells.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to identify a tRF, tRF36, that promotes AP progression by regulating the ferroptosis of pancreatic acinar cells and to elucidate the molecular mechanism whereby tRF36 is involved in AP progression (e.g., tRF36 regulates the ferroptosis of pancreatic acinar cells by regulating P53 expression through binding to IGF2BP3). The findings fill the knowledge gap by revealing how tRFs are involved in AP progression via the regulation of ferroptosis and provide a new direction for further studies on AP development.

The present study had some limitations. The sample size of the study cohort was small. Future studies should employ a larger sample size to further verify the expression of tRF36 in AP. The expression levels of ROS and MDA were determined only by knocking down tRF36. Accordingly, their expression should also be examined by overexpressing tRF36.

In this study, the most significantly differentially expressed candidate, tRF36, was identified using bioinformatics and validated using qRT-PCR based on serum RNA extraction and small RNA sequencing data from AP patients and healthy controls. The AP cell model and the AP mouse model were constructed to explore the role and mechanism of tRF36 in regulating ferroptosis and promoting AP progression, indicating that tRF36 might recruit IGF2BP3 to the p53 mRNA m6A modification site by binding to IGF2BP3 to enhance p53 mRNA stability and promote the ferroptosis of pancreatic follicle cells. This finding provides a theoretical basis for gaining further insights into the pathogenesis of AP and identifying new potential therapeutic targets.

Acute pancreatitis (AP), also known as acute inflammation of the pancreas, is an inflammatory injury resulting from the activation of pancreatic enzymes caused by a variety of pathogenic factors, leading to self-digestion of pancreatic tissue.

Difficult treatment, high morbidity, many complications, high cost, and poor prognosis are the current clinical status. Therefore, it is particularly important to investigate the pathogenesis of AP.

Screening for tRNA-derived fragments (tRFs) contribute to AP progression and exploring the molecular mechanism of its action were the main objectives of our study.

Firstly, key tRFs and the potential mechanisms of action were explored based on the small RNA sequencing and functional enrichment analyses in AP. The role of tRF36 was investigated by constructing the AP cell and mouse models. Subsequently, the lipase, amylase, and cytokine levels were assayed to examine AP progression. Evaluation of cellular ferroptosis was implemented by analyzing the ferritin expression, reactive oxygen species, malondialdehyde, and ferric ion levels. Finally, RNA pull down assays and methylated RNA immunoprecipitation were performed to explore the molecular mechanisms.

In total, 211 differentially expressed tRFs including 116 upregulated and 95 downregulated were identified. According to reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction, tRF36 was significantly upregulated in the serum of AP patients, compared to healthy controls. Moreover, the occurrence of pancreatic cell ferroptosis was detected in AP cells and mouse models. Furthermore, we hypothesized that tRF36 accelerated AP progression by binding to insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA binding protein 3, which was recruited to the p53 mRNA m6A modification site, thereby enhancing the stability of p53 mRNA and promoting ferroptosis in pancreatic follicular cells.

tRF36 promoted AP development by regulating the ferroptosis of pancreatic cells, which would provide a new theoretical basis for understanding the regulatory mechanism of tRF in AP, and also provide new targets for the treatment of AP.

We will further validate the results of this study and continue to monitor the role of tRF36 in the development process of AP.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Nagaya M, Japan; Tzeng IS, Taiwan S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yuan YY

| 1. | Li CL, Jiang M, Pan CQ, Li J, Xu LG. The global, regional, and national burden of acute pancreatitis in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021;21:332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Schepers NJ, Bakker OJ, Besselink MG, Ahmed Ali U, Bollen TL, Gooszen HG, van Santvoort HC, Bruno MJ; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Impact of characteristics of organ failure and infected necrosis on mortality in necrotising pancreatitis. Gut. 2019;68:1044-1051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 280] [Article Influence: 46.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wolbrink DRJ, Kolwijck E, Ten Oever J, Horvath KD, Bouwense SAW, Schouten JA. Management of infected pancreatic necrosis in the intensive care unit: a narrative review. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26:18-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mayerle J, Sendler M, Hegyi E, Beyer G, Lerch MM, Sahin-Tóth M. Genetics, Cell Biology, and Pathophysiology of Pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:1951-1968.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 229] [Article Influence: 38.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bai Y, Lam HC, Lei X. Dissecting Programmed Cell Death with Small Molecules. Acc Chem Res. 2020;53:1034-1045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tang D, Chen X, Kang R, Kroemer G. Ferroptosis: molecular mechanisms and health implications. Cell Res. 2021;31:107-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1891] [Cited by in RCA: 2354] [Article Influence: 588.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Dai E, Han L, Liu J, Xie Y, Zeh HJ, Kang R, Bai L, Tang D. Ferroptotic damage promotes pancreatic tumorigenesis through a TMEM173/STING-dependent DNA sensor pathway. Nat Commun. 2020;11:6339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 247] [Cited by in RCA: 282] [Article Influence: 56.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Liu K, Liu J, Zou B, Li C, Zeh HJ, Kang R, Kroemer G, Huang J, Tang D. Trypsin-Mediated Sensitization to Ferroptosis Increases the Severity of Pancreatitis in Mice. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;13:483-500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Liu J, Zhu S, Zeng L, Li J, Klionsky DJ, Kroemer G, Jiang J, Tang D, Kang R. DCN released from ferroptotic cells ignites AGER-dependent immune responses. Autophagy. 2022;18:2036-2049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Li J, Bu X, Chen X, Xiong P, Chen Z, Yu L. Predictive value of long non-coding RNA intersectin 1-2 for occurrence and in-hospital mortality of severe acute pancreatitis. J Clin Lab Anal. 2020;34:e23170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Krishna S, Raghavan S, DasGupta R, Palakodeti D. tRNA-derived fragments (tRFs): establishing their turf in post-transcriptional gene regulation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2021;78:2607-2619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pandey KK, Madhry D, Ravi Kumar YS, Malvankar S, Sapra L, Srivastava RK, Bhattacharyya S, Verma B. Regulatory roles of tRNA-derived RNA fragments in human pathophysiology. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2021;26:161-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yang H, Zhang H, Chen Z, Wang Y, Gao B. Effects of tRNA-derived fragments and microRNAs regulatory network on pancreatic acinar intracellular trypsinogen activation. Bioengineered. 2022;13:3207-3220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sun B, Chen Z, Chi Q, Zhang Y, Gao B. Endogenous tRNA-derived small RNA (tRF3-Thr-AGT) inhibits ZBP1/NLRP3 pathway-mediated cell pyroptosis to attenuate acute pancreatitis (AP). J Cell Mol Med. 2021;25:10441-10453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117419] [Cited by in RCA: 133213] [Article Influence: 5550.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Zhang KY, Rosenkrantz L, Sellers ZM. Chemically Induced Models of Pancreatitis. Pancreapedia. 2022;. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Lampel M, Kern HF. Acute interstitial pancreatitis in the rat induced by excessive doses of a pancreatic secretagogue. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol. 1977;373:97-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 413] [Cited by in RCA: 408] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Saluja A, Saito I, Saluja M, Houlihan MJ, Powers RE, Meldolesi J, Steer M. In vivo rat pancreatic acinar cell function during supramaximal stimulation with caerulein. Am J Physiol. 1985;249:G702-G710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Itzkowitz SH, Sands BE, Ullman TA, Rustgi AK. Mark Warren Babyatsky, MD (June 29, 1959-August 25, 2014). Gastroenterology. 2014;147:1189-1190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tu HJ, Zhao CF, Chen ZW, Lin W, Jiang YC. Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF) Signaling Protects Against Acute Pancreatitis-Induced Damage by Modulating Inflammatory Responses. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:e920684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bi Z, Liu Y, Zhao Y, Yao Y, Wu R, Liu Q, Wang Y, Wang X. A dynamic reversible RNA N6-methyladenosine modification: current status and perspectives. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:7948-7956. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Chen D, Chu B, Yang X, Liu Z, Jin Y, Kon N, Rabadan R, Jiang X, Stockwell BR, Gu W. iPLA2β-mediated lipid detoxification controls p53-driven ferroptosis independent of GPX4. Nat Commun. 2021;12:3644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 59.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chu B, Kon N, Chen D, Li T, Liu T, Jiang L, Song S, Tavana O, Gu W. ALOX12 is required for p53-mediated tumour suppression through a distinct ferroptosis pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2019;21:579-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 246] [Cited by in RCA: 639] [Article Influence: 106.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lei G, Zhang Y, Hong T, Zhang X, Liu X, Mao C, Yan Y, Koppula P, Cheng W, Sood AK, Liu J, Gan B. Ferroptosis as a mechanism to mediate p53 function in tumor radiosensitivity. Oncogene. 2021;40:3533-3547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 33.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Li Y, Cao Y, Xiao J, Shang J, Tan Q, Ping F, Huang W, Wu F, Zhang H, Zhang X. Inhibitor of apoptosis-stimulating protein of p53 inhibits ferroptosis and alleviates intestinal ischemia/reperfusion-induced acute lung injury. Cell Death Differ. 2020;27:2635-2650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 364] [Article Influence: 72.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Jiang L, Kon N, Li T, Wang SJ, Su T, Hibshoosh H, Baer R, Gu W. Ferroptosis as a p53-mediated activity during tumour suppression. Nature. 2015;520:57-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1173] [Cited by in RCA: 2364] [Article Influence: 236.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Conlon M, Poltorack CD, Forcina GC, Armenta DA, Mallais M, Perez MA, Wells A, Kahanu A, Magtanong L, Watts JL, Pratt DA, Dixon SJ. A compendium of kinetic modulatory profiles identifies ferroptosis regulators. Nat Chem Biol. 2021;17:665-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 26.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Sun Y, Berleth N, Wu W, Schlütermann D, Deitersen J, Stuhldreier F, Berning L, Friedrich A, Akgün S, Mendiburo MJ, Wesselborg S, Conrad M, Berndt C, Stork B. Fin56-induced ferroptosis is supported by autophagy-mediated GPX4 degradation and functions synergistically with mTOR inhibition to kill bladder cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12:1028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 42.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Hsieh CH, Hsieh HC, Shih FS, Wang PW, Yang LX, Shieh DB, Wang YC. An innovative NRF2 nano-modulator induces lung cancer ferroptosis and elicits an immunostimulatory tumor microenvironment. Theranostics. 2021;11:7072-7091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 44.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Natarajan SK, Pachunka JM, Mott JL. Role of microRNAs in Alcohol-Induced Multi-Organ Injury. Biomolecules. 2015;5:3309-3338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Tirronen A, Hokkanen K, Vuorio T, Ylä-Herttuala S. Recent advances in novel therapies for lipid disorders. Hum Mol Genet. 2019;28:R49-R54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Li YK, Yan LR, Wang A, Jiang LY, Xu Q, Wang BG. RNA-sequencing reveals the expression profiles of tsRNAs and their potential carcinogenic role in cholangiocarcinoma. J Clin Lab Anal. 2022;36:e24694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Hou W, Xie Y, Song X, Sun X, Lotze MT, Zeh HJ 3rd, Kang R, Tang D. Autophagy promotes ferroptosis by degradation of ferritin. Autophagy. 2016;12:1425-1428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1171] [Cited by in RCA: 1621] [Article Influence: 180.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Goodarzi H, Liu X, Nguyen HC, Zhang S, Fish L, Tavazoie SF. Endogenous tRNA-Derived Fragments Suppress Breast Cancer Progression via YBX1 Displacement. Cell. 2015;161:790-802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 457] [Cited by in RCA: 648] [Article Influence: 72.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |