Published online Jul 14, 2023. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v29.i26.4136

Peer-review started: April 21, 2023

First decision: May 15, 2023

Revised: May 26, 2023

Accepted: June 13, 2023

Article in press: June 13, 2023

Published online: July 14, 2023

Processing time: 79 Days and 16.7 Hours

The world is experiencing reflections of the intersection of two pandemics: Obesity and coronavirus disease 2019. The prevalence of obesity has tripled since 1975 worldwide, representing substantial public health costs due to its comor

Core Tip: The world faces a pandemic of obesity and metabolic diseases. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors’ (PPARs’) target genes regulate several metabolic pathways, alleviating obesity and its metabolic impairments. PPARα exerts relevant anti-inflammatory, anti-steatotic, and pro-thermogenic effects, collaborating with weight loss and insulin resistance alleviation. PPARγ is useful for glycemic management, albeit with caution due to side effects after its total activation. PPARβ/δ is not clinically used owing to a pro-tumorigenic profile. However, Pan-PPAR or dual-PPAR agonists can retain PPARβ/δ or partial PPARγ activation benefits and configure promising approaches to treat metabolic diseases alone or in combination with other drug classes.

- Citation: Souza-Tavares H, Miranda CS, Vasques-Monteiro IML, Sandoval C, Santana-Oliveira DA, Silva-Veiga FM, Fernandes-da-Silva A, Souza-Mello V. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors as targets to treat metabolic diseases: Focus on the adipose tissue, liver, and pancreas. World J Gastroenterol 2023; 29(26): 4136-4155

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v29/i26/4136.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v29.i26.4136

The unprecedented obesity rates have become an immense public health problem due to increased costs to treat comorbidities like diabetes, cancer, osteoarticular diseases, and cardiovascular events[1]. Most obesity cases stem from a chronic positive energy balance, where surplus energy intake surpasses the energy expenditure (EE), sending excessive energy to the adipose tissue[2,3].

The white adipose tissue (WAT) is a buffer against excess energy from the diet and first undergoes hyperplasia and hypertrophy and preserves its different types of cell composition[4,5]. As this process continues, preadipocytes become rare, and hypertrophy predominates until the adipocyte reaches its maximal capacity to enlarge, parallel to a rarefaction of vascularization and the high amount of proinflammatory immune cells within the stromal vascular fraction of the WAT[6,7]. At this stage, inflammation and insulin resistance activates lipolysis to allow the storage of the continuing excessive energy from the diet at the expense of diverting the non-esterified fatty acids (NEFAs) from lipolysis to organs not specialized to store lipids like the liver and the pancreas (lipotoxicity), triggering steatosis[8,9].

Hepatic and pancreatic steatosis compromises the physiology of these organs, collaborating with the progression to end-stage liver diseases and diabetes[10-12]. Thus, the scientific community seeks for strategies to mitigate the deleterious effects of obesity and its comorbidities, which affects the worldwide population regardless of economic income or age. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) are a family of transcription factors linked to the cellular metabolism of lipids, carbohydrates, proteins, and cell proliferation, existing in three isoforms: PPARα, PPARβ/δ, and PPARγ and emerged in recent decades as a strategy to treat obesity and its complications[13].

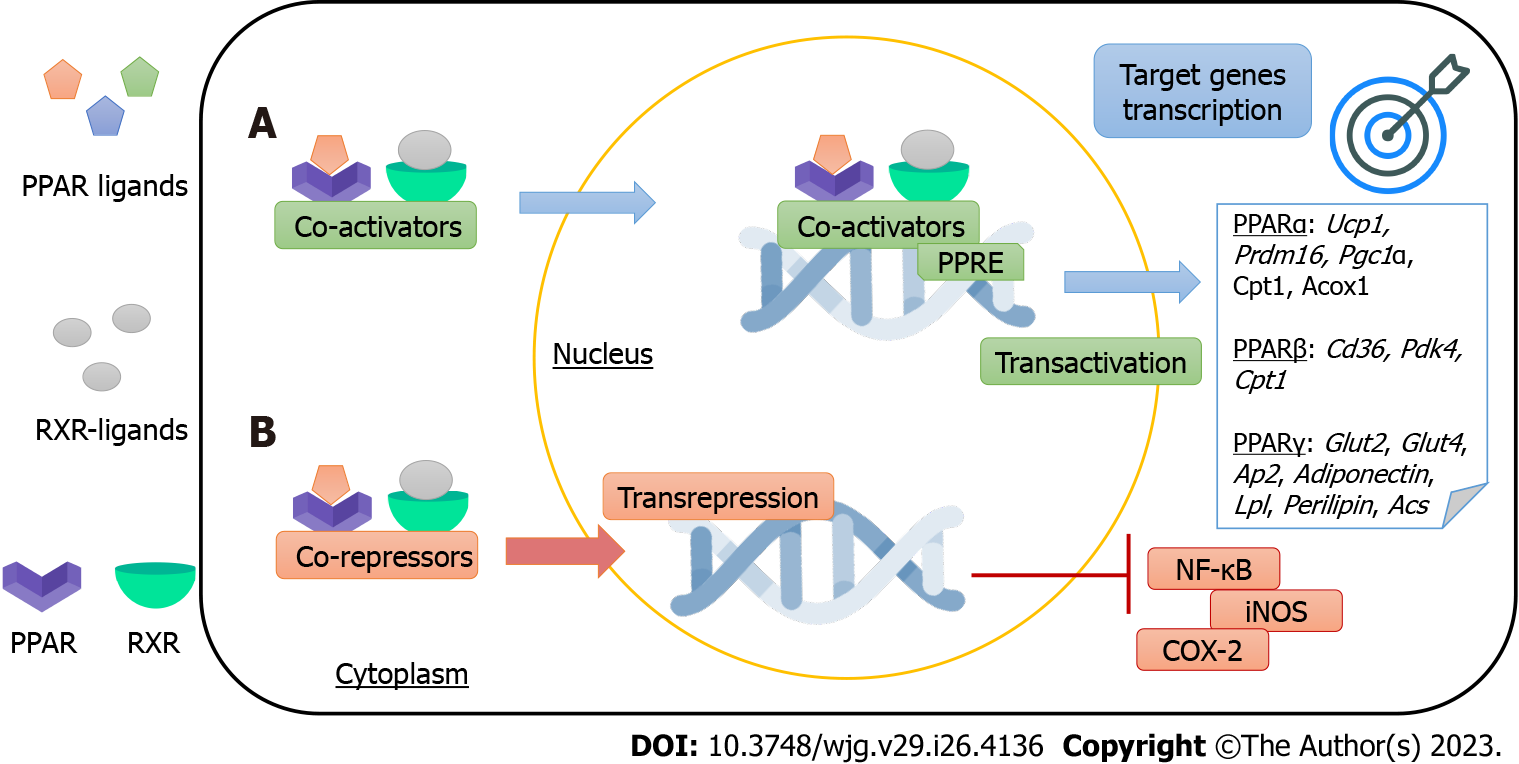

PPARs are binding-dependent transcription factors that regulate gene expression by specifically binding to PPAR-responsive elements (PPREs). Each receptor heterodimerizes with the retinoid X receptor (RXR, where X can be α, β/δ, or γ) and binds to its respective PPRE, forming a structure that will recognize specific DNA sequences (AGGTCA) for the transcription of their target genes. This PPAR mechanism of action is known as trans-activation. Moreover, PPARs can regulate gene expression independently of binding to PPREs, through the mechanism of trans-repression. There is a crosstalk between PPARs and other transcription factors that regulate their gene expression, and most of the anti-inflammatory effects of PPARs stem from this mechanism[14,15]. Figure 1 summarizes PPARs mechanisms of action.

PPARs regulate countless metabolic pathways after activation by endogenous ligands, such as fatty acids and their derivatives or synthetic agonists, which trigger a conformational change to interact with transcriptional coactivators[16,17]. The PPARα isoform expression is high in the liver, muscle, and heart, and its activation, according to previous studies, suggests that this receptor participates in lipid metabolism. PPARγ is mainly expressed in white and brown adipose tissue (BAT), being responsible, among other functions, for adipogenesis. Finally, PPARβ/δ has a wide body distribution with described roles in fatty acids oxidation in muscle and general energy regulation[13].

PPARs exert their physiological activities by activating the transcription of their target genes and, in this way, regulate lipid metabolism, glucose homeostasis, cell differentiation, obesity, and cancer. Furthermore, PPARs may directly participate in immune responses and inflammation mechanisms[18].

Considering that PPARs are found at the intersection of several metabolic pathways, influencing glucose homeostasis, adiposity, and mitochondrial function in the liver, this review aimed to update the potential of PPAR agonists as targets to treat metabolic diseases, focusing on adipose tissue plasticity, hepatic, and pancreatic remodeling.

In mammals, the adipose organ comprises two types of tissues: WAT and BAT. Depending on the adipose tissue origin (for example, gonadal or subcutaneous), differences occur in its lipolytic or lipogenic capacity[19].

The white adipocytes are the only cells specialized in storing lipids without compromising their functional integrity. They have the necessary enzymatic machinery to synthesize triacylglycerol (TAG) when the energy supply is abundant and to mobilize them through lipolysis when there is an energy deficit[20].

The autonomic nervous system acts directly on the adipose tissue. The sympathetic nervous system promotes catabolic actions (lipolysis) via adrenergic stimulation, which activates the hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) enzyme[21]. Conversely, the parasympathetic nervous system yields anabolism by stimulating insulin secretion, increasing glucose uptake, and activating lipogenesis[22].

Regarding the mature white adipocyte characteristics, it stores TAG in a single large lipid droplet that occupies the central portion of the cell, promoting displacement of the nucleus to the periphery and its consequent flattening. The single lipid droplet occupies 85%-95% of the cell volume, characterizing the white adipocyte as unilocular[23,24].

WAT, described as the chief energy reservoir in mammals, has a mesenchymal origin and is composed of adipocytes and the stromal vascular fraction (the main constituent of pre-adipocytes, immune cells, and fibroblasts); together, adipocytes and the stromal vascular fraction produce the extracellular matrix to maintain the structural and functional integrity of the tissue[25,26].

For a long time, the WAT was a secondary structure whose characteristic was the reservoir of large amounts of fat in the form of TAG. There was a lack of attention to its participation in body weight and food intake control. As a result of the discovery of the ability of WAT to secrete substances with biological effects like leptin in 1994, known collectively as adipokines, WAT emerged as a major endocrine organ[27,28].

Conversely, BAT has a smaller adipocyte than WAT, exhibiting several cytoplasmic lipid droplets of different sizes (multilocular), relatively abundant cytoplasm, spherical and slightly eccentric nucleus, and numerous mitochondria that produce energy by oxidizing acids[29]. The brownish BAT coloration stems from its high mitochondrial content, whose uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) is one of the primary markers for brown adipocyte identification[30,31].

The brown adipocytes specialize in performing nonshivering thermogenesis (NST), by which the UCP1 acts as an alternative channel in the inner mitochondrial membrane to the proton gradient in the intermembrane space return to the mitochondrial matrix without resulting in ATP synthesis. Instead, the chemical energy is released as heat, enhancing the body temperature and EE, a promising target to treat obesity through negative energy balance[32,33].

Brown adipocytes originate from myocyte progenitor cells (myogenic lineage) and express the myogenic factor 5. Prdm16 controls a bidirectional cell fate switching between skeletal myoblasts and brown adipose cells. Loss of the PR domain containing 16 (Prdm16) in brown fat precursors causes loss of brown fat characteristics and promotes muscle differentiation[34]. Prdm16 induces a complete program of brown fat differentiation, including the expression of PPAR-gamma coactivator 1α (Pgc-1α) and Ucp-1. Pgc-1α is an essential transcriptional coactivator for NST and mitochondrial biogenesis[35].

Although BAT total mass in mammals is small, previous research has already shown that its adequate stimulation (cold exposure, specific drugs, some food compounds, or physical activity) could quadruple the EE of an animal, parallel to an increase in tissue perfusion[36-38]. Thus, understanding the damage obesity causes to BAT morphology and physiology can help to develop strategies to treat obesity.

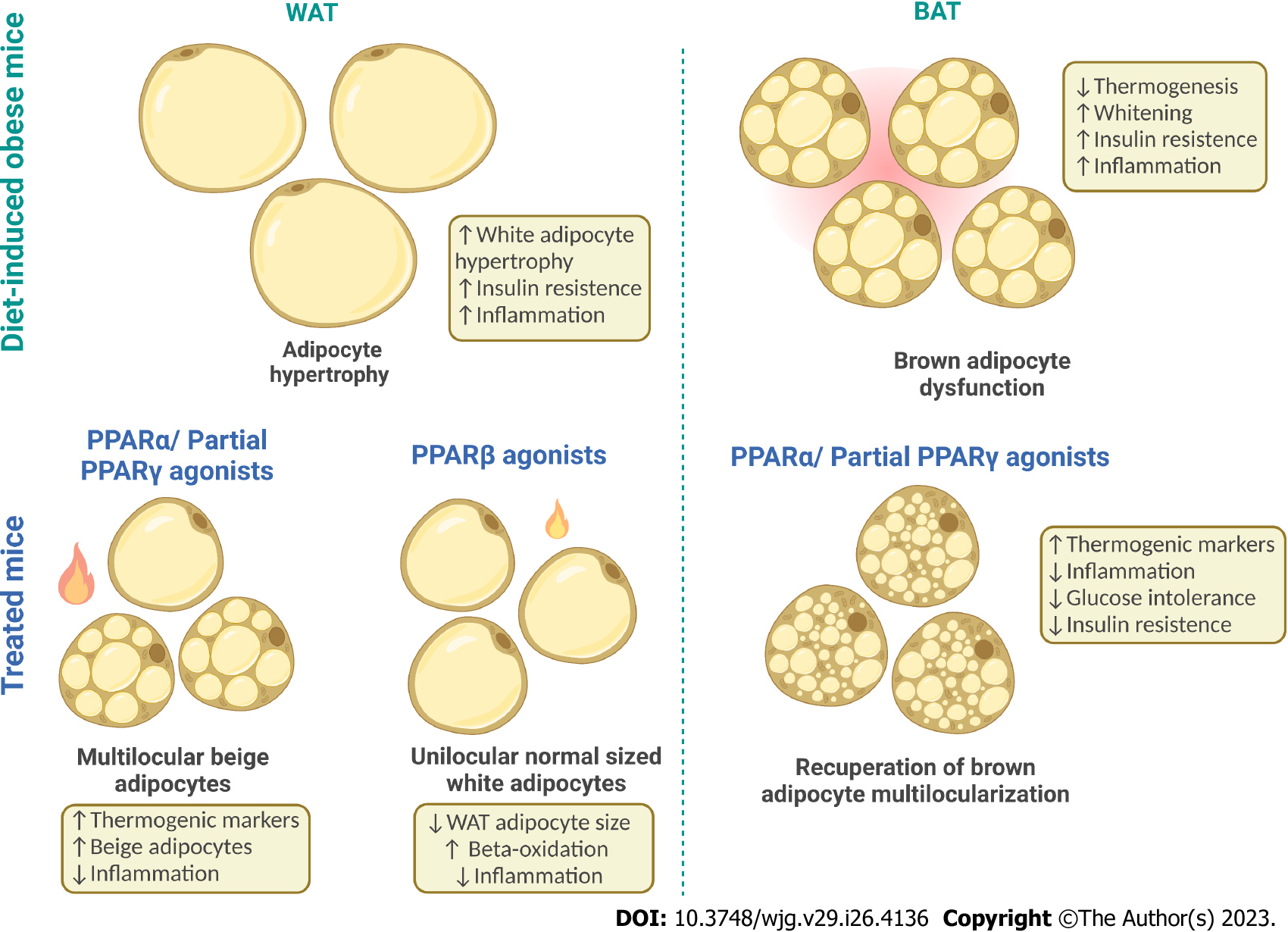

Recently, experimental studies reported that diet-induced obesity (DIO) results in glucose intolerance, functional BAT hypoxia, and structural whitening. Brown adipocytes in obese animals reduce their thermogenic capacity and assume a white phenotype, becoming unilocular[39,40]. The molecular mechanisms that lead to reduced BAT activity in obesity and its physiological implications are under investigation, and altered PPAR expression may have a role in the whitening phenomenon as Pparα expression declines in whitened BAT[41]. Compared to WAT, BAT is more extensively vas

Since obesity is a public health problem in developed and developing countries, the world urges us to find new approaches to treat or prevent this metabolic disease and its comorbidities. WAT plasticity towards an intermediary adipocyte between white and brown, the beige adipocyte, may emerge as a suitable strategy to fight the obesity pandemic[43].

Beige adipocytes are found in the subcutaneous WAT (sWAT) and exhibit a brown-like adipocyte phenotype (multilocular). In the basal state, beige adipocytes act like white adipocytes, but under the right stimulus, they can acquire intermediate mitochondrial content and perform thermogenesis, a process called browning[44]. Prdm16 is essential to the browning phenomenon once its down-regulation turns a beige adipocyte into a white one, showing that browning is reversible and morphophysiological changes rely on adequate PRDM16 expression and active mitochondrial biogenesis machinery to increase mitochondrial content and thermogenic capacity[45,46].

Beige adipocytes originate from mature white adipocytes [low expression of the cluster of differentiation 137 (Cd137)], which under specific stimulation, acquire a brown-like phenotype, or even from a beige pre-adipocyte (high Cd137), which differentiates into a multilocular cell capable of performing thermogenesis. The latter originates from a lineage different from the WAT[47,48]. Although the beige adipocytes have a lower thermogenic activity than the brown adipocytes, their presence is linked to a metabolically healthy phenotype in humans[49], reducing the chances of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), hepatic steatosis, and other metabolic constraints.

The metabolic benefits of beige/brown adipocytes presence also stem from their endocrine role in secreting the batokines. Like the adipokines from the WAT, batokines act in autocrine, paracrine, and endocrine fashions to provide increased neurovascular supply to BAT, favoring thermogenesis and inhibiting whitening besides exerting anti-inflammatory effects, favoring browning, and influencing glucose homeostasis[50]. Figure 2 depicts white and BAT plasticity under obesogenic and thermogenic stimuli.

The recent literature suggests that less than 100 g of adipose tissue in an adult human with thermogenic activity can prevent 4 kg of fat accumulation per year[51], stimulating the search for drugs that trigger browning while inhibiting whitening, relevant for metabolic disease control.

PPARα was the first receptor discovered, mapped to chromosome 22q12-13.1 in humans, found in metabolically active tissues such as the liver, kidney, heart, skeletal muscle, and brown fat[52,53]. PPARα has polyunsaturated fatty acids and leukotrienes as natural ligands, which are inflammatory mediators; as pharmacological ligands, the family of hypolipidemic drugs, fibrates, is considered an accessible PPARα agonist[54].

The participation of PPARα in the thermogenic pathway involves directing NEFAs, generated after adrenergic stimulation, to the β-oxidation instead of cellular efflux. β-adrenergic stimulus mobilizes most of NEFA in normal conditions, and this mobilization is related to the inflammatory response and the reduction of cell function in the long term. The chronic stimulation of the beta-3 adrenergic receptor upregulates PPARα expression, increasing adipocytes’ oxidative capacity[55].

Natural or pharmacological ligands mainly control the expression of genes involved in lipid metabolism. If the concentration of fatty acids increases, PPARα is activated and absorbs the oxidized forms of these acids. During the influx of fatty acids, the transcription of PPARα-regulated genes increases, and the systems are activated[55,56]. Thus, PPARα functions as a lipid sensor and controls energy combustion.

A previous study showed that treatment with WY14643 (PPARα agonist) exerted lipolytic effects with reduced fat mass and increased whole-body fat oxidation. These results demonstrate a novel role for PPARα activation in beta-adrenergic regulation of adipose tissue lipolysis[57]. In addition, treatment with WY-14643 has already shown effects in reducing hepatic steatosis, serum insulin, and inflammation in adipose tissue, and these changes are generally observed in obesity onset[58,59].

In BAT, PPARα stimulates lipid oxidation and thermogenesis in synergy with PGC1α[60]. In this scenario, a study demonstrated that the activation of PPARα by a pharmacological agent (fenofibrate) activated NST (and mitochondrial biogenesis in the BAT of obese mice fed a high-fat diet[61]. Subsequently, the chronic intake of a high-fat diet caused BAT whitening, and the treatment with WY14643 mitigated this morphophysiological impairment through anti-inflammatory signals and enhanced VEGFA, resulting in increased thermogenesis. In the same experiment, the high-fructose diet did not trigger whitening, but the WY14643 also attenuated the histological changes caused by excessive dietary fructose[62].

PPARα is the isoform that induces the browning of sWAT more abundantly. Fenofibrate has yielded expressive browning in DIO mice, with an irisin-Pgc1α-Prdm16 interaction driven by PPARα stimulating thermogenesis and mitigating insulin resistance and inflammation, countering obesity[63]. Confirming these results, the PPARα agonist WY14643 yielded Cd137/Prdm16/Ucp1+ beige adipocytes, whereas the PPARβ/δ agonist GW0742 reduced sWAT adipocyte size and increased beta-oxidation without browning induction[59]. PPARβ/δ activation by GW501516 countered adipocyte hypertrophy through suppression of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE)/angiotensin II receptor type 1 (AT1r) axis and downstream potent anti-inflammatory effects[64].

PPARγ received much attention since the mid-1990s as the molecular target of thiazolidinediones (TZDs) or glitazones, a class of insulin-sensitizing and antidiabetic drugs[65]. PPARγ, a transcription factor from the nuclear receptor family, plays a significant role in lipid and glucose metabolism regulation[66]. WAT and BAT, large intestine, and spleen express PPARγ. However, its expression is much higher in adipocytes[67,68].

Ligand-activated PPARγ induces adipocyte differentiation, stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis, and inhibits the production of pro-inflammatory mediators[68]. In addition, PPARγ activated in adipocytes ensures a balanced and adequate secretion of adipokines (adiponectin and leptin), mediators of insulin action in peripheral tissues[69].

In WAT, PPARγ is pivotal to lipid accumulation. In contrast, PPARγ activation in BAT induces the expression of genes related to the thermogenic program, including Pgc1α and Ucp1. PPARγ is crucial for brown adipocyte differentiation, but additional transcription factors, including PRDM16, are required to activate the thermogenic program[70].

The PPARγ1 isoform is expressed in almost all cells, while PPARγ2 is mainly limited to adipose tissue. However, PPARγ2 is a more potent transcriptional activator[71]. Both PPARγ1 and PPARγ2 are essential for adipogenesis and insulin sensitivity control. However, PPARγ2 is the isoform upregulated in response to nutrient intake and obesity[72,73].

TZDs, synthetic PPARγ ligands, are antidiabetic drugs with potent insulin-sensitizing effects that confer long-term glycemic control[74]. However, its clinical use has been contested due to side effects such as weight gain, edema, and bone fractures[75]. The increase in body weight after TZDs administration is due to PPARγ-dependent WAT expansion[76] and fluid retention caused by PPARγ activation in the renal collecting ducts[77].

TZDs improve peripheral insulin sensitivity and have a spectrum of anti-inflammatory properties, including a reduction in plasma inflammatory markers and adipose tissue macrophages[72,78]. In WAT, TZDs promote adipocyte differentiation, insulin action, and the formation of beige adipocytes[66]. In BAT, TZDs activate thermogenic activity[79].

The dual PPARα/γ agonist tesaglitazar reversed iBAT whitening through gut dysbiosis and ultrastructure improvements[80]. Intestinal PPARα activation suppresses postprandial hyperlipidemia by increasing the fatty acid oxidation of intestinal epithelial cells[81]. In addition, intestinal PPARα activation reduces cholesterol esterification, suppresses chylomicron production, and increases enterocytes’ HDL synthesis[82]. These observations pave a new way to treat metabolic diseases through the modulation of gut microbiota by PPARs and the consequent gut-adipose tissue stimulation of thermogenesis due to anti-inflammatory, angiogenic, and high beta-adrenergic signaling[80]. Figure 2 shows the main PPAR effects on the adipose tissue.

The human pancreas is a mixed gland made up of five anatomical divisions: Head (fitted with the duodenum), uncinate process, neck, body, and tail (nearby the spleen); measures 15-25 cm in length; and weighs 100 g to 150 g in a healthy adult[83]. The inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery, the superior pancreaticoduodenal artery, and the splenic artery are responsible for its perfusion, and the pancreatic plexus, celiac ganglia, and vagus nerve innervate this gland[84,85].

The pancreas has endocrine and exocrine functions, encompassing four structural components: The exocrine portion, constituted by acinar and ductal cells; the endocrine region formed by the islet cells; the blood vessels; and the extracellular space[84]. The exocrine portion corresponds to 85% of the pancreas volume, comprehending a ductal system like a bunch of grapes with a blinded end. Each acinus corresponds to a grape and secretes pancreatic juice enzymes that flow into bicarbonate-secreting ductal epithelial cells[83,84]. After passing through accessory ducts, these enzymes reach the main pancreatic duct that connects with the bile duct in the ampulla of Vater in the duodenum. The exocrine pancreatic secretion (amylase, lipase, and zymogens) helps to digest proteins, fats, and carbohydrates, being secreted by the autonomic nervous system stimulation in the presence of food in the duodenum and the consequent release of secretin, cholecystokinin, and other hormones by the enteroendocrine cells[83].

The endocrine portion of the pancreas comprises mini-organs called islets of Langerhans, corresponding to 1%-2% of the total pancreatic volume. Pancreatic islets have a spherical shape and secrete hormones related to glucose homeostasis. There are five islet cell types: Alpha cells (α cells, produce glucagon), beta cells (β cells, insulin), delta cells (δ cells, somatostatin), PP cells (also known as F cells, pancreatic polypeptide-containing cells), and epsilon cells (ε cells, ghrelin). Neuroendocrine, endocrine, paracrine, and endocrine mechanisms influence islet secretion. Therefore, overactivation or inactivation of their regulatory pathways can drastically impact the metabolism, causing metabolic diseases[86-88].

The most prevalent cell types in pancreatic islets are alpha and beta cells. In mice, alpha cells are restricted to the islet periphery, while the beta cells found in the core of the islet are vastly innervated and comprehend 60%-80% of the total islet mass. In humans, alpha and beta cells are interspersed all around the islets, with beta cells comprising 50%-75% of the islet mass with a sparse innervation. The remaining islet cell types do not differ significantly between men and mice. Even though there are cytoarchitectural differences regarding the islets of these species, the dynamics of islet remodeling in obesity and T2DM are similar and propitiates relevant translational studies[87].

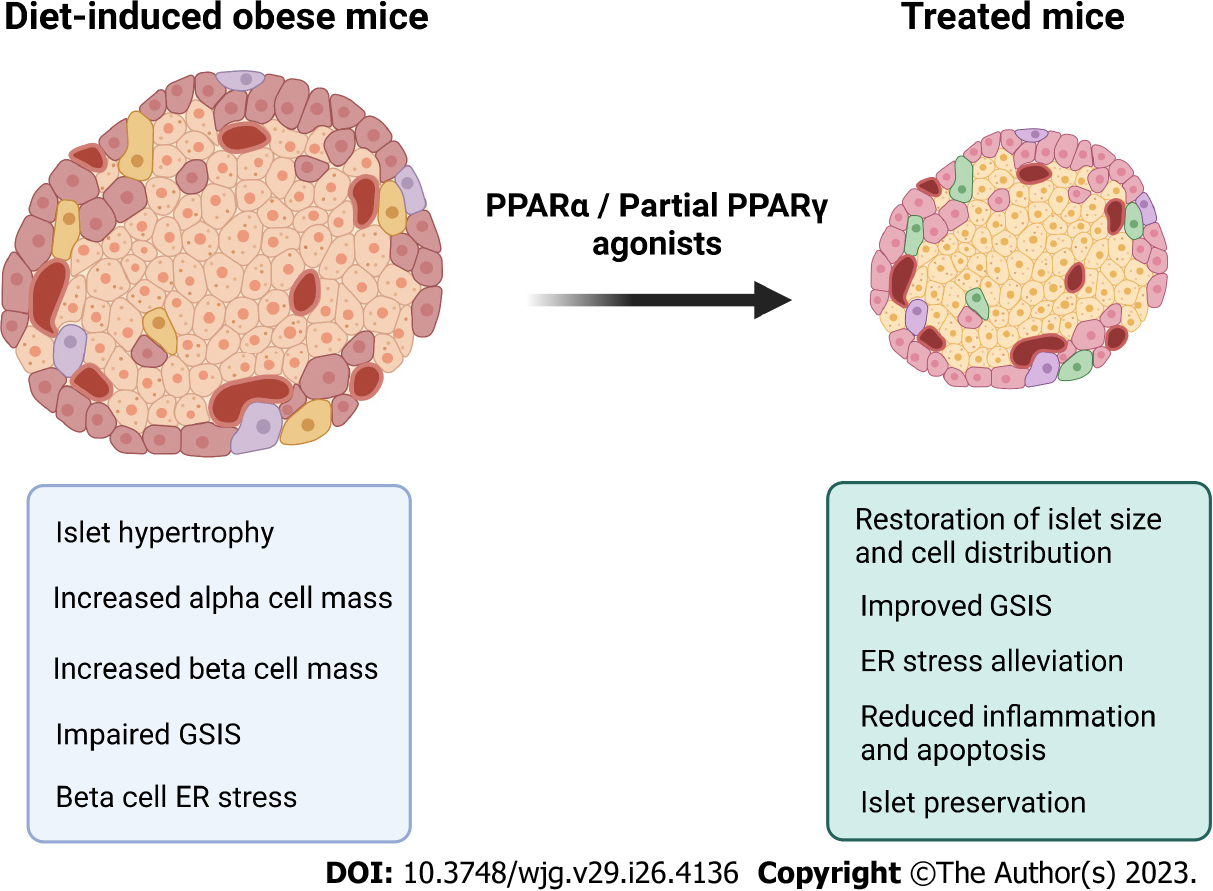

Obesity entails an impaired glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) triggered by the adipoinsular axis deregulation due to increased demand for insulin release. The resistance to insulin action relates to hyperleptinemia, prompted by the inflamed hypertrophied WAT[89,90]. Under an insulin-resistant state, the glucose fails to enter the pancreatic beta cell, resulting in a high demand for insulin to keep euglycemia. Islet hypertrophy and hypersecretion are commonplace features in DIO mice as the expansion of alpha and beta cell masses cope with normal glycemic levels maintenance at the beginning of glucose homeostasis impairments[91-93].

Insulin resistance (IR) precedes the T2DM diagnosis by around ten years[94]. Initially, the compensatory hyperinsulinemia prompts normal fasting glucose levels (IR). As adiposity evolves, hyperinsulinemia cannot cope with adequate glycemic control. At this point, raised plasma insulin and glucose concentrations coexist, characterizing glucose intolerance[91,95]. Glucose-intolerant mice exhibit hyperglycemia, alpha cells infiltrated to the islet core, besides a disrupted GSIS, with endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and loss of beta cell polarity, compromising its secretion and threatening islet survival[96,97].

Glucotoxicity (hyperglycemia) elicits ER stress, which leads to proinsulin misfolding and accumulation, a hallmark of beta cell dysfunction and T2DM onset[98]. Beta cell dysfunction originates from continuing islet hypertrophy and hypersecretion (lipotoxicity), impaired GSIS, beta cell ER stress (glucolipotoxicity), and downregulation of proliferative markers like the pancreatic duodenal homeobox-1 (PDX1)[96,99]. Compromised beta cell proliferation, increased apoptosis rate, and dedifferentiation result in beta cell failure[100]. T2DM is linked to a decreased beta cell mass (-22%-63%) and begins when beta cell mass cannot compensate for the high demand for insulin to sustain glucose homeostasis[101].

As a multi-hormonal disease, T2DM entails decreased beta cell mass coupled with the loss of incretin effect. Incretins are gut-derived hormones that enhance insulin secretion and sensitivity after meal ingestion, participating in the glycemic control at the postprandial state. Chronic high-fat diets lead to loss of the incretin glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) capacity to enhance beta cell responsiveness to glucose and proliferation, resulting in beta cell exhaustion[102,103]. Loss of incretin effect occurs even with normal GLP-1 and gastric inhibitory polypeptide levels in obese subjects, suggesting a possible resistance to their actions like described for insulin and leptin[104].

To avoid the progression of IR towards T2DM onset, therapies that could promote pancreatic alpha cell transdifferentiation into beta cells to maintain glycemic control are promising approaches to tackle beta cell exhaustion and reduced beta cell mass[105]. In this context, PPARs may be therapeutic targets for glycemic homeostasis.

PPARs regulate the expression of several target genes and allow the proper functioning of pathways linked to energy metabolism. An imbalance of these pathways can lead to the development of T2DM and other disorders[106,107]. Thus, PPARs are relevant therapeutic targets for the clinical management of diabetes.

Numerous drugs have been used and developed for the treatment of hyperlipidemia and T2DM such as PPARα agonists (fibrates, e.g., fenofibrate, bezafibrate and clofibrate) and PPARγ agonists (TZDs, e.g., troglitazone, rosiglitazone, pioglitazone and ciglitazone). PPARβ/δ does not have a role well-established in glucose metabolism, but it is known to improve insulin sensitivity by facilitating fatty acid oxidation in some tissues and reducing glucose oxidation[108,109].

PPARα plays an essential role in glucose homeostasis and regulates enzymes and proteins involved in glucose synthesis in the fasting state[110]. In addition, it stimulates pancreatic beta cells and increases fatty acid oxidation and GSIS[111]. Fenofibrate and fish oil countered islet hypertrophy and increased adiponectin levels in diabetic KK mice[112], mitigating lipotoxicity-induced beta cell dysfunction by inhibiting the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and reducing macrophage migration[113]. In agreement, fenofibrate exerted anti-inflammatory and antiapoptotic effects besides enhancing islet innervation in young non-obese diabetic mice, providing adequate glucose handling, and preventing diabetes-associated diseases[114].

Conversely, Fenofibrate long-term use (12 wk, 100 mg/kg) disrupted beta cell function due to increased NF-κB and inducible nitric oxide synthase islet expression in monosodium glutamate-induced obese rats[115]. An in vitro study showed that PPARα activation by WY14643 or bezafibrate (pan-PPAR agonist) enhances GSIS. However, long-term treatments contribute to beta cell dysfunction owing to overstimulation[116]. In a clinical study, bezafibrate showed that parameters related to insulin resistance were attenuated during the follow-up period, while the placebo group showed an increase in this parameter over two years[117].

PPARγ, in turn, controls glucose homeostasis as it increases glucose transporter (GLUT4) expression and its translocation in adipocytes, causing adipose remodeling by reducing visceral fat deposits while selectively increasing sWAT, resulting in a possible insulin sensitization scenario[118,119]. Furthermore, studies have shown that PPARγ activation increases adipocytes’ fatty acid uptake, reducing lipotoxic damage to insulin-sensitive tissues[120], increasing glucose uptake by skeletal muscle, and consequent peripheral reduction[120,121].

PPARγ agonists are the most developed antidiabetic and insulin-sensitizing agents to date. Studies have shown that TZDs (or glitazones) bind specifically to the ligand binding domain (LBD) of recombinant PPARγ but not to PPARα or PPARβ/δ. These agents also selectively stimulate the activity of the PPARγ gene promoter and modulate the expression of several of its target genes[122]. TZDs class increases glucose catabolism and reduces its hepatic production[123,124], sensitizes cells to insulin, improves insulin sensitivity and action[125,126], and promotes pre-adipocyte differentiation along with lipogenesis, which favors a reduction in NEFAs concentrations, attributed to increased glucose utilization and reduced gluconeogenesis.

Human and animal studies indicate that the TZDs (total PPARγ agonists) rosiglitazone and pioglitazone improve hyperglycemia by reversing insulin resistance and improving insulin sensitivity. In addition, both agents also show significant effects on plasma lipoprotein lipids in humans, although pioglitazone results in a relatively better lipid profile than rosiglitazone[127,128]. Of note, the clinical use of rosiglitazone was discouraged owing to the unwanted effects of fluid retention, arterial vasodilation, endothelial alterations[129,130], increased risk of bone fracture and congestive heart failure[131], and weight gain in both animal models and humans due to the master regulatory role of PPARγ in adipogenesis[66].

Pioglitazone (15 mg/kg per mouse) yielded healthy pancreatic islets in db/db mice, enhancing insulin and NK6 homeobox 1 expression and restoring islet function in this mice model[132]. The islet preservation due to PPARγ activation by pioglitazone encompasses anti-inflammatory effects and alleviation of ER stress[133]. Pioglitazone and vildagliptin (DPP-4 inhibitor) combination maximized pioglitazone’s effects on suppressed inflammation and oxidative stress in male rats[134]. In agreement with this, pioglitazone plus sitagliptin enhanced alpha and beta cell functions at the postprandial state in T2DM subjects[135].

Telmisartan, a partial PPARγ agonist and angiotensin receptor blocker, reduces serum insulin levels and mitigates insulin resistance without affecting serum adiponectin levels[136]. The experimental background shows that telmisartan reduced islet hypertrophy, with adequate glycemic control and normalized alpha and beta cell mass in DIO mice. These effects were maximized by telmisartan combination with sitagliptin, reverting oral glucose intolerance and normalizing body mass in this DIO model[93]. Telmisartan combination with linagliptin promoted islet preservation by suppressing oxidative stress[137].

The beneficial effects of telmisartan on islet cytoarchitecture featured ultrastructural remodeling, with polarized cells and mature insulin granules reestablished after the treatment[97]. Telmisartan elicited enhanced islet vascularization, enhanced PDX1 and GLP-1 islet expression plasma concentrations, ameliorating GSIS and preserving pancreatic islets through reduced apoptosis rate and macrophage infiltration[96]. Due to improved islet proliferation capacity, telmisartan might be a candidate for beneficial islet cell transdifferentiation to slow insulin resistance to T2DM onset progression. Figure 3 summarizes the main effects of PPARα and partial PPAR γ agonists on the endocrine pancreas.

Drugs with specificity for at least two PPAR isoforms (e.g., dual PPARα/γ or pan-PPAR agonists) could be more effective and have relatively fewer undesirable side effects compared with currently used agonists with specificity for a single PPAR isoform[138]. In this context, a series of dual PPARα/γ agonists, named glitazars, was designed to combine total PPARα and partial PPARγ activation, retaining the insulin-sensitizing property of PPARγ target genes with the beneficial effects of PPARα activation on energy metabolism[139,140]. However, muraglitazar showed many of the same side effects (weight gain and edema) in patients[141,142], having glitazars development halted due to safety concerns.

Research is ongoing to develop new PPAR agonists without side effects. Since PPARs orchestrate many physiological processes, agonists may play beneficial or non-beneficial effects. So, PPAR actions on pancreatic islets need elucidation to support the development of new drugs with more assertive outcomes.

The liver is a complex organ that concentrates on several physiological processes as macronutrient metabolism, immune system support, fatty acid, and cholesterol homeostasis, besides the degradation of xenobiotic compounds and many medications[143]. It is the largest solid glandular organ in the body. With versatile endocrine and exogenous functions, the liver is considered paramount for metabolic activities[144]. It has a remarkably uniform anatomical structure composed of the regular arrangement of lobules that are the functional unit of the liver. The base of the lobule is composed of hepatocytes, the most prevalent cells of the liver[145]. Hepatocytes arranged between the sinusoids along the portal-central axis demonstrate heterogeneity concerning their biochemical and physiological functions[146]. Additional cell types within the liver include cholangiocytes, Kupffer cells, stellate cells, and endothelial cells, with specialized functions[147].

The liver is enriched with cell organelles to fulfill its metabolic functions. It is one of the organs with the highest number and density of mitochondria, which interact with other organelles such as ER, lipid deposits (LDs), and lysosomes[148,149]. In the gastrointestinal tract, food digestion generates metabolic substrates (glucose, fatty acids, and amino acids) that are absorbed by the bloodstream and conducted to the liver through the portal vein circulation system. In the postprandial state, glucose forwards to glycogen storage, and the excess undergoes de novo lipogenesis (DNL) in the liver. DNL forms new TAG from acetyl-CoA or malonyl-CoA[150,151].

In mammals, acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) and fatty acid synthase (FAS)-an enzyme intricately regulated by several nuclear receptors (NRs, e.g., PPARα, PPARγ, and the bile acid receptor/farnesoid X receptor) catalyze fatty acid production. NRs are also relevant mediators of insulin signaling, whereas DNL occurs under anabolic conditions, linking glucose and lipid metabolism. Further support of this link encompasses insulin stimulation of FAS expression. In hepatocytes, NEFAs are esterified with glycerol-3-phosphate to synthesize TAG. TAG is stored in LDs within hepatocytes or secreted into the circulation as very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) particles. In the fasted state or during exercise, fuel substrates (glucose and TAG) are delivered from the liver into the circulation and metabolized by muscle, adipose tissue, and other extrahepatic tissues[150,151]. However, the increased intake of dietary lipids, associated with upregulated DNL process, causes lipotoxicity and the abnormal accumulation of lipids, often consistent with insulin resistance in steatotic livers, which is related to disturbed ER protein folding homeostasis in hepatocytes[152,153].

The ER in hepatocytes can adapt to extracellular and intracellular changes, allowing the maintenance of essential hepatic metabolic functions. However, several alterations can disturb the ER homeostasis of hepatocytes, contributing to the dysregulation of hepatic lipid metabolism and liver diseases. Consequently, ER includes a progressively conserved pathway called unfolded protein response (UPR) to control liver protein and lipid homeostasis[154]. UPR decreases secretory protein quantity, increases ER protein folding (chaperone and foldase transcription), and enhances deletion capacity by stimulating autophagy and ER-related degradation[152]. Thus, ER stress is a cellular stress in which the demand for folding newly synthesized proteins exceeds ER capacity to fold or to correct it through UPR, generating unfolded protein accumulation[155].

The existence of three transmembrane-ER proteins is understood to reveal and transduce the ER stress response: Protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase (PERK), inositol-requiring protein-1α (IRE-1α) and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6). Activation of ATF6 and PERK elicit the expression of the C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP), whereas IRE-1α induces the activation of the N-terminal C-Jun kinase and also generates an improved form of X-box binding protein-1 (XBP1), the spliced XBP1, which attempts to the depletion of misfolded ER proteins through chaperone, folding proteins, and ERAD components encoding[156].

However, when ER stress is intense to the point that damage is irreversible, the ER cannot restore its function. Hence, inflammatory responses trigger cell death pathways[157]. There is strong communication between ER homeostasis perturbations and mitochondrial dysfunction in the onset of obesity and metabolic syndrome. The mitochondrion organelle plays an essential role in hepatic cellular redox, lipid metabolism, and cell death regulation[158], and genes related to mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation are mostly transcriptionally regulated by PPARα[159]. Fatty acids input into the mitochondria requires carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1a (Cpt1a) (a PPARα target gene), located in the outer mitochondrial membrane. PPARα activation leads to the transcription of Cpt1a, associated with fatty acid oxidation in mitochondria, peroxisomes (acyl-CoA oxidase, ACOX), and cytochrome P450 4A family[160].

Mitochondrial dysfunction is associated with acute and chronic liver diseases, and relevant information indicates that mitophagy, a selective form of autophagy (catabolic process, which manifests itself by selective sequestration of mitochondria by autophagosomes, phagophores, a double membrane that isolates autophagic components)[161] of dysfunctional/excessive mitochondria, plays a pivotal role in liver physiology and pathophysiology[158]. There are specificities and mechanisms mediating mitophagy, many of them mediated by the FUN14 domain containing 1 (FUNDC1), a mitochondrial outer membrane protein tightly regulated at transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels. NRF1 (nuclear respiratory factor 1) and PGC1α, the major transcription factor and related cofactor in mitochondrial biogenesis, beneficially adjust FUNDC1 expression and enhance mitophagy[162]. Therefore, mitophagy favors mitochondrial remodeling, and PPARs are implicated in this pathway[163]. Figure 4 summarizes liver alterations under lipotoxicity in obesity.

Functional studies have demonstrated that PPARα governs hepatic expression of genes involved in nearly all aspects of lipid metabolism, including fatty acid uptake, elongation and desaturation, activation and binding of intracellular fatty acids, formation and degradation of TGs and lipid droplets, and metabolism from plasma lipoproteins[164,165]. The constitutive activity of mitochondrial β-oxidation was significantly reduced in the liver of mice lacking the Pparα gene (Pparα null mice)[166]. Pparα knockout mice fed a high-fat diet increased markers of oxidative stress, inflammation, and cell death[167].

Thus, PPARα has been the target of hypolipidemic drugs from the fibrate family, under investigation for treating non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). PPARα upregulates fatty acid β-oxidation and lipolysis, upregulating the expression of several genes involved in lipid metabolism (Pgc1α and Cpt1a), leading to less fat accumulation in NAFLD[168]. Pgc1α modulates the expression of key metabolic enzymes involved in gluconeogenesis, fatty acid oxidation, and oxidative phosphorylation in the liver through their functional interaction with PPARα[169]. Mitochondrial β-oxidation of long-chain fatty acids is regulated by CPT1a, an enzyme physiologically inhibited by malonyl-CoA, a glucose-derived metabolite and an intermediate in DNL synthesis[170].

Administration of Wy-14643, one of the most potent PPARα agonists, decreased serum insulin, rescued hyperglycemia, and suppressed carbohydrate response element binding protein (ChREBP), mitigating steatosis and hepatic damage. The reductions in ChREBP and FAS activity likely reflect the diminished stimulatory effects of glucose on ChREBP and as a substrate (AcylCoA) for fatty acid synthesis[171]. Moreover, WY-14643 markedly reduced hepatic steatosis in high-fat-fed C57BL/6 mice by augmenting the volume density of mitochondria per area of liver tissue and downregulating hepatic gluconeogenesis and DNL[58]. More recently, WY-14643 treated gut dysbiosis in high-fat and high-fructose-fed-mice, exerting antisteatotic effects through diminished endotoxemic inflammatory inputs to the liver, showing that PPARα mitigates liver steatosis by acting on multiple hits that trigger this outcome[172,173].

Fibrates are a less potent but clinically relevant class of PPARα agonists compared to Wy-14643, which have also been evaluated in experimental models and human studies[174]. In vivo experiments, treatment with pemafibrate, a selective PPARα agonist, identify PPARα as a pharmacological, sexually dimorphic target primarily related to related gene functions to lipid homeostasis, with the female liver being much more responsive to pemafibrate than the male liver[175]. The potency of synthetic PPARα agonists may differ from receptor to species as measured using the PPARα-GAL4 transactivation system, i.e., fenofibrate (mouse receptor, EC50 = 18000 nM vs human receptor, EC50 = 30000 nM), bezafibrate (EC50 = 90000 nM vs 50000 nM, respectively) and Wy14643 (EC50 = 630 nM vs 5000 nM, respectively)[176].

In contrast, several studies have provided evidence that hepatic PPARγ expression markedly increases in many models of obesity (lipoatrophy and hyperphagic obesity), insulin resistance, and diabetes with varying degrees of steatosis[177]. PPARγ expression in the liver is low under healthy conditions but increases as steatosis develops in rodents[178]; this effect is not seen in humans[75,179]. They have tremendous potential in patients with NAFLD because they promote preadipocyte differentiation into adipocytes and may induce fat redistribution from visceral sites such as the liver and muscle to peripheral subcutaneous adipose tissue, increase circulating adiponectin levels, and improve insulin sensitivity[180].

PPARγ agonists, such as the TZDs, stimulate genes that favor the storage of TAG, thus lowering circulating free fatty acid concentrations[181]. In humans, one-year treatment with pioglitazone (at low dosage) significantly improved liver steatosis, inflammation, and systemic and local adipose tissue insulin resistance in patients with T2D. A decrease in sterol regulatory element-binding transcription factor 1c (SREBP-1c) expression by pioglitazone has a primary effect in reducing hepatic steatosis[182]. Pooled results suggest that acetaldehyde produced from ethanol metabolism may increase the synthesis of the mature SREBP-1 protein, which increases hepatic lipogenesis, thus leading to the development of fatty liver[183,184].

Administration of the PPARγ agonist rosiglitazone (5 mg/kg, daily, gavage) accelerated regression of liver fibrosis as associated with increased expression of PPARγ in mice, with similar findings in human hepatic stellate cells (HSCs). Furthermore, in vitro, GATA binding protein 6 (GATA6)-deficient HSCs exhibit a defect in inactivation, suggesting that GATA6 and PPARγ agonists can be used to drive the inactivation of HSCs/myofibroblasts and could compose a combination strategy to halt liver fibrosis in patients[185]. On the other hand, some studies associate TZD therapy with an average weight gain of 4 kg to 5 kg[186,187]. Weight gain combines adiposity and fluid retention as the increased peripheral edema observed during the pre-marketing clinical trials of pioglitazone and rosiglitazone. Increased vascular permeability through high vascular endothelial growth factor secretion and decreased systemic vascular resistance are non-kidney factors that contribute to this edema[188,189].

Recently, dual PPAR-α/γ agonists emerged as a strategy to lessen undesirable side effects related to PPAR-γ agonism. In a randomized controlled clinical trial, Saroglitazar (PPAR-α/γ agonist, 4 mg) significantly improved alanine transaminase, liver fat content, insulin resistance, and atherogenic dyslipidemia in participants with NAFLD/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)[190]. In an in vitro study on HepG2 cells, saroglitazar prevented HSC activation from quiescent cells to highly proliferative and fibrogenic cells. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, upregulated in NAFLD, can activate hepatic stellate cells, causing increased collagen deposition that initiates fibrogenesis. In turn, the use of saroglitazar reduced the expression of pro-inflammatory [tumor necrosis factor-alpha (Tnfα), interleukin (IL)-1β, and IL-6] and pro-fibrogenic (monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, transforming growth factor beta, collagen type I alpha 1 chain, and α-smooth muscle actin) genes in HSC[191]. Evidence is growing in favor of dual PPARα/γ agonism as a candidate for the treatment of NAFLD/NASH due to findings of improvements in all components responsible for these conditions.

In agreement with PPARα beneficial effects on the liver, PPARβ/δ possesses anti-inflammatory effects in the liver by inhibiting NF-κB activity by directly binding to its subunit p65[192-195]. The PPAR-β/δ agonist GW0742 Led to the modulation of the inflammatory response induced by NF-κB in rats, reducing the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and neutrophils infiltration into the liver[193,196]. During the induction of inflammatory responses, the inactivated PPARβ/δ participates in the activation of NF-κB p65. Activation by ligand PPARβ/δ results in a lack of this cooperation, and consequently, activation of PPARβ/δ interferes with the function of NF-κB p65. As a result, inflammatory responses caused by a high concentration of glucose, activation of the receptor for TNF-α, IL-1β, or activation of TLR4 are reduced[197]. Along with the anti-inflammatory effects, GW0742 has recently mitigated hepatic steatosis through attenuating hepatic ER stress (reduced p-eIF2α/ATF4/CHOP expression), yielding anti-apoptotic signals and favored beta-oxidation over lipogenesis in high-fat-fed mice[198].

Despite this, the contribution of PPARβ/δ to hepatic lipid metabolism is still controversial. PPAR-β/δ null mice on a high-fat diet showed an increased rate of hepatic VLDL production and an increase in the plasma VLDL apoB48, apoE, apoAI, and apoAII levels, as well as a reduction in hepatic lipid stores[178]. However, the other potent PPARβ/δ agonist, GW501516, increased the expression of the lipogenic enzyme ACC2 and consequently increased the hepatic TAG content in db/db mice[192,199]. The role that PPAR-β/δ has on liver metabolism is not defined as there is not a PPAR-β/δ agonist available to the population[200]. Figure 5 depicts the beneficial effects of PPAR activation on the liver. Table 1 shows the main mechanisms and endpoints of PPAR agonists on experimental, in vitro, and clinical backgrounds.

| Model | PPAR agonist | Effect/mechanism | Ref. |

| HF diet fed C57BL/6 mice (14 wk) | WY14643 (3.0 mg/kg BM) | Decreased body mass and increased hepatic beta-oxidation | Barbosa-da-Silva et al[57], 2015 |

| HF diet fed C57BL/6 mice (14 wk) | WY14643 (2.5 mg/kg BM) | Decreased insulin, hepatic steatosis, and enhanced mitochondria per area of liver tissue | Veiga et al[58], 2017 |

| HF diet fed C57BL/6 mice (14 wk) | WY14643 (2.5 mg/kg BM) | Browning of subcutaneous WAT, increased thermogenesis | Rachid et al[59], 2018 |

| HF diet or high-fructose-fed C57BL/6 mice (17 wk) | WY14643 (3.5 mg/kg BM) | Reduced whitening in HF-fed mice via increased VEGFA and reduced inflammation | Miranda et al[62], 2020 |

| HF diet fed C57BL/6 mice (15 wk) | Fenofibrate (100.0 mg/kg BM) | Increased irisin-Pgc1α-Prdm16 and induced thermogenic beige adipocytes | Rachid et al[63], 2015 |

| High-fructose diet-fed C57BL/6 mice (11 wk) | GW501516 (3.0 mg/kg/d) | Potent anti-inflammatory effects that reversed adipocyte hypertrophy | Magliano et al[64], 2015 |

| Knockout mice for Pparγ in collecting duct | Rosiglitazone (320.0 mg/kg diet) | PPARγ regulates sodium transport in the collecting ducts and mediates the rosiglitazone-induced edema | Zhang et al[77], 2005 |

| Human subcutaneous white adipose tissue biopsy | Pioglitazone (45 mg daily for two months) | Pioglitazone reduced CD68 and MCP-1 expression in adipose tissue, improving insulin sensitivity | Di Gregorio et al[78], 2005 |

| HF diet fed C57BL/6 mice (16 wk) | Tesaglitazar (4 mg/kg BM) | PPARα/γ synergism treated dysbiosis and favored thermogenesis | Miranda et al[80], 2023 |

| Human jejunal biopsies | Cells treated with GW7647 (600 nM) or GFT505 (1 μM) for 18 h | Intestinal PPARα activation induces HDL production | Colin et al[82], 2013 |

| Knockout mice | 25.0% fish oil in the diet | Increased adiponectin, improved glucose metabolism, and islet hypertrophy | Nakasatomi et al[112], 2018 |

| Non-obese diabetic mice | 0.1% fenofibrate in the diet | Anti-inflammatory, antiapoptotic effects, and enhanced islet innervation, ameliorating glucose handling | Holm et al[114], 2019 |

| Monosodium glutamate induced obese rats | 100 mg/kg fenofibrate for 12 wk | Long-term treatment disrupted beta cell function due to increased NF-κB and iNOS expression | Liu et al[115], 2011 |

| Rat pancreatic islets in vitro | 300 microM bezafibrate for 8 h | Bezafibrate enhanced GSIS through Pparα activation in short-term culture. Long-term culture caused beta cell dysfunction due to overstimulation | Yoshikawa et al[116], 2001 |

| Diabetic subjects | 400 mg bezafibrate for two years | Bezafibrate avoided the progressive decline of beta cell function and insulin resistance increase | Tenenbaum et al[117], 2007 |

| Subjects diagnosed with type 2 diabetes and dyslipidemia | Pioglitazone 30 mg/d for 12 wk and 45 mg/d for additional 12 wk; rosiglitazone 4 mg/d for 12 wk and 8 mg/d for additional 12 wk | Pioglitazone had better effects regarding improvements in triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, LDL particle concentration, and LDL particle size | Goldberg et al[127], 2005 |

| db/db mice | Pioglitazone 15 mg/kg BM for 18 d | Restoration of pancreatic islet function with increased expression of insulin and NK6 Homeobox 1 expression | Collier et al[132], 2021 |

| Knockout-Ay mice | High-fat diet plus pioglitazone 0.02% for 6 wk | Islet preservation through ER stress and inflammation alleviation | Hong et al[133], 2018 |

| Diabetic Wistar rats (low streptozotocin dose) | 10 mg/kg pioglitazone or vildagliptin or their combination for 4 wk | Vildagliptin maximized pioglitazone effects on inflammation and oxidative stress attenuation | Refaat et al[134], 2016 |

| Type 2 diabetic patients | Sitagliptin 100 mg/d or Pioglitazone 30 mg/d or their combination for 12 wk | Both drugs exerted complementary effects on blood glucose control | Alba et al[135], 2013 |

| Non-diabetic hypertensive subjects | Telmisartan (80 mg/d) for 6 wk | Telmisartan enhanced insulin sensitivity in hypertensive patients independent of adiponectin induction | Benndorf et al[136], 2006 |

| High-fat diet-fed mice (16 wk) | Telmisartan (5 mg/kg BM) alone or in combination with sitagliptin (1 g/kg BM) or metformin (300 mg/kg BM) | Treated animals exhibited marked mitigation of hepatic steatosis and islet hypertrophy; telmisartan combination with sitagliptin normalized alpha and beta cell mass | Souza-Mello et al[93], 2010; Souza-Mello et al[97], 2011 |

| High-fat diet-fed mice (15 wk) | Telmisartan (10 mg/kg) | Amelioration of endocrine pancreas structure and function, with enhanced islet vascularization and reduced apoptosis rate | Graus-Nunes et al[96], 2017 |

| db/db mice | Telmisartan (3 mg/kg BM), linagliptin (3 mg/kg BM) or their combination for eight weeks | Combined therapy provided better results than the monotherapies on glucose homeostasis, islet cell functions, and structure via reduced oxidative stress | Zhao et al[137], 2016 |

| High-fat-fed foz/foz obese/diabetic mice for 16 wk | WY14643 (0.1% w/w) for 10 d or 20 d | PPARα activation mitigated steatosis, and hepatocyte ballooning, besides reducing NF-κB and JNK activation. Persistent adipose-derived MCP1 enhanced levels may limit its property to treat NASH | Larter et al[171], 2012 |

| High-fructose diet-fed mice (17 wk) | WY14643 (3.5 mg/kg BM) or linagliptin (15.0 mg/kg BM) or their combination | The WY14643 monotherapy or its combination with linagliptin-treated dysbiosis, controlling endotoxemia and mitigating liver steatosis | Silva-Veiga et al[173], 2020 |

| Type 2 diabetic patients | Metformin 2 g/d + Pioglitazone (15 mg/d, 30 mg/d, or 45 mg/d) | All pioglitazone doses exerted similar effects, with mitigation of liver steatosis and inflammation, with improved systemic insulin resistance | Della Pepa et al[182], 2021 |

| CCl4-injured mice | Rosiglitazone (5 mg/kg BM) for two weeks | Rosiglitazone blocked liver fibrosis progression through the down-regulation of fibrogenic genes and HSCs inactivation | Liu et al[185], 2020 |

| Patients with NAFLD/NASH | Saroglitazar 1 mg, 2 mg, or 4 mg for 16 wk | Saroglitazar 4 mg significantly mitigated insulin resistance and atherogenic dyslipidemia | Gawrieh et al[190], 2021 |

| HF diet fed mice (14 wk) | GW0742 (1 mg/kg BM) for four weeks | PPARβ/δ mitigated hepatic steatosis through improved insulin resistance and ER stress alleviation | Silva-Veiga et al[198], 2018 |

Overall, there is no doubt that PPARs are promising therapeutic targets for metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and NAFLD/NASH. However, more research, improvement, and testing are needed to apply PPAR-targeted agents to human metabolic diseases with increased safety and efficacy. Much as PPARs agonists are widely prescribed to treat dyslipidemia, hypertension, and T2DM, dual agonists are promising in the context of obesity due to the combination of anti-inflammatory, lipid oxidation, insulin-sensitizing, and thermogenesis activation, which prevails from one of the isoforms actions and might be highlighted with suitable modulation of their combined activation. Considering that the jury is still out on defined drug therapy for obesity and NAFLD (one of obesity’s more prevalent comorbidity), PPARs entail a potent target to reach adequate control of the glucolipotoxicity that trigger metabolic diseases, whether as part of a combination of different PPARs isoforms or combined with agents from other drug classes.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Biochemistry and molecular biology

Country/Territory of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Morozov S, Russia; Wu QN, China S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yuan YY

| 1. | GBD 2015 Obesity Collaborators, Afshin A, Forouzanfar MH, Reitsma MB, Sur P, Estep K, Lee A, Marczak L, Mokdad AH, Moradi-Lakeh M, Naghavi M, Salama JS, Vos T, Abate KH, Abbafati C, Ahmed MB, Al-Aly Z, Alkerwi A, Al-Raddadi R, Amare AT, Amberbir A, Amegah AK, Amini E, Amrock SM, Anjana RM, Ärnlöv J, Asayesh H, Banerjee A, Barac A, Baye E, Bennett DA, Beyene AS, Biadgilign S, Biryukov S, Bjertness E, Boneya DJ, Campos-Nonato I, Carrero JJ, Cecilio P, Cercy K, Ciobanu LG, Cornaby L, Damtew SA, Dandona L, Dandona R, Dharmaratne SD, Duncan BB, Eshrati B, Esteghamati A, Feigin VL, Fernandes JC, Fürst T, Gebrehiwot TT, Gold A, Gona PN, Goto A, Habtewold TD, Hadush KT, Hafezi-Nejad N, Hay SI, Horino M, Islami F, Kamal R, Kasaeian A, Katikireddi SV, Kengne AP, Kesavachandran CN, Khader YS, Khang YH, Khubchandani J, Kim D, Kim YJ, Kinfu Y, Kosen S, Ku T, Defo BK, Kumar GA, Larson HJ, Leinsalu M, Liang X, Lim SS, Liu P, Lopez AD, Lozano R, Majeed A, Malekzadeh R, Malta DC, Mazidi M, McAlinden C, McGarvey ST, Mengistu DT, Mensah GA, Mensink GBM, Mezgebe HB, Mirrakhimov EM, Mueller UO, Noubiap JJ, Obermeyer CM, Ogbo FA, Owolabi MO, Patton GC, Pourmalek F, Qorbani M, Rafay A, Rai RK, Ranabhat CL, Reinig N, Safiri S, Salomon JA, Sanabria JR, Santos IS, Sartorius B, Sawhney M, Schmidhuber J, Schutte AE, Schmidt MI, Sepanlou SG, Shamsizadeh M, Sheikhbahaei S, Shin MJ, Shiri R, Shiue I, Roba HS, Silva DAS, Silverberg JI, Singh JA, Stranges S, Swaminathan S, Tabarés-Seisdedos R, Tadese F, Tedla BA, Tegegne BS, Terkawi AS, Thakur JS, Tonelli M, Topor-Madry R, Tyrovolas S, Ukwaja KN, Uthman OA, Vaezghasemi M, Vasankari T, Vlassov VV, Vollset SE, Weiderpass E, Werdecker A, Wesana J, Westerman R, Yano Y, Yonemoto N, Yonga G, Zaidi Z, Zenebe ZM, Zipkin B, Murray CJL. Health Effects of Overweight and Obesity in 195 Countries over 25 Years. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:13-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5669] [Cited by in RCA: 5066] [Article Influence: 633.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Betz MJ, Enerbäck S. Human Brown Adipose Tissue: What We Have Learned So Far. Diabetes. 2015;64:2352-2360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tseng YH, Cypess AM, Kahn CR. Cellular bioenergetics as a target for obesity therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:465-482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 486] [Cited by in RCA: 459] [Article Influence: 30.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gustafson B, Hedjazifar S, Gogg S, Hammarstedt A, Smith U. Insulin resistance and impaired adipogenesis. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2015;26:193-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 242] [Cited by in RCA: 273] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gustafson B, Smith U. Regulation of white adipogenesis and its relation to ectopic fat accumulation and cardiovascular risk. Atherosclerosis. 2015;241:27-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cildir G, Akıncılar SC, Tergaonkar V. Chronic adipose tissue inflammation: all immune cells on the stage. Trends Mol Med. 2013;19:487-500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 225] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gustafson B, Hammarstedt A, Hedjazifar S, Smith U. Restricted adipogenesis in hypertrophic obesity: the role of WISP2, WNT, and BMP4. Diabetes. 2013;62:2997-3004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | DeFronzo RA. Dysfunctional fat cells, lipotoxicity and type 2 diabetes. Int J Clin Pract Suppl. 2004;9-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Longo M, Zatterale F, Naderi J, Parrillo L, Formisano P, Raciti GA, Beguinot F, Miele C. Adipose Tissue Dysfunction as Determinant of Obesity-Associated Metabolic Complications. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 457] [Cited by in RCA: 1013] [Article Influence: 168.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Polyzos SA, Kountouras J, Mantzoros CS. Adipose tissue, obesity and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Minerva Endocrinol. 2017;42:92-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Poitout V, Robertson RP. Minireview: Secondary beta-cell failure in type 2 diabetes--a convergence of glucotoxicity and lipotoxicity. Endocrinology. 2002;143:339-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 403] [Cited by in RCA: 447] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Saponaro C, Gaggini M, Carli F, Gastaldelli A. The Subtle Balance between Lipolysis and Lipogenesis: A Critical Point in Metabolic Homeostasis. Nutrients. 2015;7:9453-9474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 370] [Article Influence: 37.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Harrington WW, S Britt C, G Wilson J, O Milliken N, G Binz J, C Lobe D, R Oliver W, C Lewis M, M Ignar D. The Effect of PPARalpha, PPARdelta, PPARgamma, and PPARpan Agonists on Body Weight, Body Mass, and Serum Lipid Profiles in Diet-Induced Obese AKR/J Mice. PPAR Res. 2007;2007:97125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Li M, Pascual G, Glass CK. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma-dependent repression of the inducible nitric oxide synthase gene. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:4699-4707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 299] [Cited by in RCA: 296] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Delerive P, De Bosscher K, Besnard S, Vanden Berghe W, Peters JM, Gonzalez FJ, Fruchart JC, Tedgui A, Haegeman G, Staels B. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha negatively regulates the vascular inflammatory gene response by negative cross-talk with transcription factors NF-kappaB and AP-1. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:32048-32054. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 832] [Cited by in RCA: 848] [Article Influence: 32.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Dubois V, Eeckhoute J, Lefebvre P, Staels B. Distinct but complementary contributions of PPAR isotypes to energy homeostasis. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:1202-1214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 278] [Article Influence: 34.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Corrales P, Vidal-Puig A, Medina-Gómez G. PPARs and Metabolic Disorders Associated with Challenged Adipose Tissue Plasticity. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Moraes LA, Piqueras L, Bishop-Bailey D. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and inflammation. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;110:371-385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 288] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Fonseca-Alaniz MH, Takada J, Alonso-Vale MI, Lima FB. Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ: from theory to practice. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2007;83:S192-S203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ahima RS, Flier JS. Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2000;11:327-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1004] [Cited by in RCA: 930] [Article Influence: 37.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Pénicaud L, Cousin B, Leloup C, Lorsignol A, Casteilla L. The autonomic nervous system, adipose tissue plasticity, and energy balance. Nutrition. 2000;16:903-908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kreier F, Fliers E, Voshol PJ, Van Eden CG, Havekes LM, Kalsbeek A, Van Heijningen CL, Sluiter AA, Mettenleiter TC, Romijn JA, Sauerwein HP, Buijs RM. Selective parasympathetic innervation of subcutaneous and intra-abdominal fat--functional implications. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1243-1250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Giralt M, Villarroya F. White, brown, beige/brite: different adipose cells for different functions? Endocrinology. 2013;154:2992-3000. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 356] [Cited by in RCA: 405] [Article Influence: 33.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lidell ME, Betz MJ, Enerbäck S. Two types of brown adipose tissue in humans. Adipocyte. 2014;3:63-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wronska A, Kmiec Z. Structural and biochemical characteristics of various white adipose tissue depots. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2012;205:194-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 262] [Article Influence: 20.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Divoux A, Clément K. Architecture and the extracellular matrix: the still unappreciated components of the adipose tissue. Obes Rev. 2011;12:e494-e503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Frederich RC, Hamann A, Anderson S, Löllmann B, Lowell BB, Flier JS. Leptin levels reflect body lipid content in mice: evidence for diet-induced resistance to leptin action. Nat Med. 1995;1:1311-1314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1136] [Cited by in RCA: 1197] [Article Influence: 39.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Lee MW, Lee M, Oh KJ. Adipose Tissue-Derived Signatures for Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes: Adipokines, Batokines and MicroRNAs. J Clin Med. 2019;8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Nedergaard J, Bengtsson T, Cannon B. Unexpected evidence for active brown adipose tissue in adult humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293:E444-E452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1260] [Cited by in RCA: 1321] [Article Influence: 73.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Langin D. Recruitment of brown fat and conversion of white into brown adipocytes: strategies to fight the metabolic complications of obesity? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1801:372-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Brown adipose tissue: function and physiological significance. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:277-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4296] [Cited by in RCA: 4774] [Article Influence: 227.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Lowell BB, Spiegelman BM. Towards a molecular understanding of adaptive thermogenesis. Nature. 2000;404:652-660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1243] [Cited by in RCA: 1212] [Article Influence: 48.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Nedergaard J, Golozoubova V, Matthias A, Asadi A, Jacobsson A, Cannon B. UCP1: the only protein able to mediate adaptive non-shivering thermogenesis and metabolic inefficiency. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1504:82-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 425] [Cited by in RCA: 468] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Timmons JA, Wennmalm K, Larsson O, Walden TB, Lassmann T, Petrovic N, Hamilton DL, Gimeno RE, Wahlestedt C, Baar K, Nedergaard J, Cannon B. Myogenic gene expression signature establishes that brown and white adipocytes originate from distinct cell lineages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4401-4406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 531] [Cited by in RCA: 549] [Article Influence: 30.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Seale P, Kajimura S, Yang W, Chin S, Rohas LM, Uldry M, Tavernier G, Langin D, Spiegelman BM. Transcriptional control of brown fat determination by PRDM16. Cell Metab. 2007;6:38-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 995] [Cited by in RCA: 944] [Article Influence: 52.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Nedergaard J, Bengtsson T, Cannon B. Three years with adult human brown adipose tissue. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1212:E20-E36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Smith RE, Hock RJ. Brown fat: thermogenic effector of arousal in hibernators. Science. 1963;140:199-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Smith RE. Thermoregulatory and adaptive behavior of brown adipose tissue. Science. 1964;146:1686-1689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Shimizu I, Aprahamian T, Kikuchi R, Shimizu A, Papanicolaou KN, MacLauchlan S, Maruyama S, Walsh K. Vascular rarefaction mediates whitening of brown fat in obesity. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:2099-2112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 251] [Cited by in RCA: 320] [Article Influence: 29.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Roberts-Toler C, O'Neill BT, Cypess AM. Diet-induced obesity causes insulin resistance in mouse brown adipose tissue. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015;23:1765-1770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Rangel-Azevedo C, Santana-Oliveira DA, Miranda CS, Martins FF, Mandarim-de-Lacerda CA, Souza-Mello V. Progressive brown adipocyte dysfunction: Whitening and impaired nonshivering thermogenesis as long-term obesity complications. J Nutr Biochem. 2022;105:109002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Xue Y, Petrovic N, Cao R, Larsson O, Lim S, Chen S, Feldmann HM, Liang Z, Zhu Z, Nedergaard J, Cannon B, Cao Y. Hypoxia-independent angiogenesis in adipose tissues during cold acclimation. Cell Metab. 2009;9:99-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 285] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Concha F, Prado G, Quezada J, Ramirez A, Bravo N, Flores C, Herrera JJ, Lopez N, Uribe D, Duarte-Silva L, Lopez-Legarrea P, Garcia-Diaz DF. Nutritional and non-nutritional agents that stimulate white adipose tissue browning. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2019;20:161-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Wu J, Boström P, Sparks LM, Ye L, Choi JH, Giang AH, Khandekar M, Virtanen KA, Nuutila P, Schaart G, Huang K, Tu H, van Marken Lichtenbelt WD, Hoeks J, Enerbäck S, Schrauwen P, Spiegelman BM. Beige adipocytes are a distinct type of thermogenic fat cell in mouse and human. Cell. 2012;150:366-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2276] [Cited by in RCA: 2580] [Article Influence: 198.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Harms MJ, Ishibashi J, Wang W, Lim HW, Goyama S, Sato T, Kurokawa M, Won KJ, Seale P. Prdm16 is required for the maintenance of brown adipocyte identity and function in adult mice. Cell Metab. 2014;19:593-604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in RCA: 312] [Article Influence: 28.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Spiegelman BM. Banting Lecture 2012: Regulation of adipogenesis: toward new therapeutics for metabolic disease. Diabetes. 2013;62:1774-1782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Sanchez-Gurmaches J, Guertin DA. Adipocyte lineages: tracing back the origins of fat. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1842:340-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Long JZ, Svensson KJ, Tsai L, Zeng X, Roh HC, Kong X, Rao RR, Lou J, Lokurkar I, Baur W, Castellot JJ Jr, Rosen ED, Spiegelman BM. A smooth muscle-like origin for beige adipocytes. Cell Metab. 2014;19:810-820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 322] [Cited by in RCA: 354] [Article Influence: 32.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Min SY, Kady J, Nam M, Rojas-Rodriguez R, Berkenwald A, Kim JH, Noh HL, Kim JK, Cooper MP, Fitzgibbons T, Brehm MA, Corvera S. Human 'brite/beige' adipocytes develop from capillary networks, and their implantation improves metabolic homeostasis in mice. Nat Med. 2016;22:312-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 244] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 27.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Martins FF, Souza-Mello V, Aguila MB, Mandarim-de-Lacerda CA. Brown adipose tissue as an endocrine organ: updates on the emerging role of batokines. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig. 2022;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Virtanen KA, Lidell ME, Orava J, Heglind M, Westergren R, Niemi T, Taittonen M, Laine J, Savisto NJ, Enerbäck S, Nuutila P. Functional brown adipose tissue in healthy adults. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1518-1525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2311] [Cited by in RCA: 2376] [Article Influence: 148.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Sher T, Yi HF, McBride OW, Gonzalez FJ. cDNA cloning, chromosomal mapping, and functional characterization of the human peroxisome proliferator activated receptor. Biochemistry. 1993;32:5598-5604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 380] [Cited by in RCA: 376] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Braissant O, Foufelle F, Scotto C, Dauça M, Wahli W. Differential expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs): tissue distribution of PPAR-alpha, -beta, and -gamma in the adult rat. Endocrinology. 1996;137:354-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1162] [Cited by in RCA: 1345] [Article Influence: 46.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Vamecq J, Latruffe N. Medical significance of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Lancet. 1999;354:141-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 359] [Cited by in RCA: 355] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Li P, Zhu Z, Lu Y, Granneman JG. Metabolic and cellular plasticity in white adipose tissue II: role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;289:E617-E626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Rösch S, Ramer R, Brune K, Hinz B. Prostaglandin E2 induces cyclooxygenase-2 expression in human non-pigmented ciliary epithelial cells through activation of p38 and p42/44 mitogen-activated protein kinases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;338:1171-1178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Barbosa-da-Silva S, Souza-Mello V, Magliano DC, Marinho Tde S, Aguila MB, Mandarim-de-Lacerda CA. Singular effects of PPAR agonists on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease of diet-induced obese mice. Life Sci. 2015;127:73-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Veiga FMS, Graus-Nunes F, Rachid TL, Barreto AB, Mandarim-de-Lacerda CA, Souza-Mello V. Anti-obesogenic effects of WY14643 (PPAR-alpha agonist): Hepatic mitochondrial enhancement and suppressed lipogenic pathway in diet-induced obese mice. Biochimie. 2017;140:106-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Rachid TL, Silva-Veiga FM, Graus-Nunes F, Bringhenti I, Mandarim-de-Lacerda CA, Souza-Mello V. Differential actions of PPAR-α and PPAR-β/δ on beige adipocyte formation: A study in the subcutaneous white adipose tissue of obese male mice. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0191365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Seale P. Transcriptional Regulatory Circuits Controlling Brown Fat Development and Activation. Diabetes. 2015;64:2369-2375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Rachid TL, Penna-de-Carvalho A, Bringhenti I, Aguila MB, Mandarim-de-Lacerda CA, Souza-Mello V. PPAR-α agonist elicits metabolically active brown adipocytes and weight loss in diet-induced obese mice. Cell Biochem Funct. 2015;33:249-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Miranda CS, Silva-Veiga F, Martins FF, Rachid TL, Mandarim-De-Lacerda CA, Souza-Mello V. PPAR-α activation counters brown adipose tissue whitening: a comparative study between high-fat- and high-fructose-fed mice. Nutrition. 2020;78:110791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Rachid TL, Penna-de-Carvalho A, Bringhenti I, Aguila MB, Mandarim-de-Lacerda CA, Souza-Mello V. Fenofibrate (PPARalpha agonist) induces beige cell formation in subcutaneous white adipose tissue from diet-induced male obese mice. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;402:86-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Magliano DC, Penna-de-Carvalho A, Vazquez-Carrera M, Mandarim-de-Lacerda CA, Aguila MB. Short-term administration of GW501516 improves inflammatory state in white adipose tissue and liver damage in high-fructose-fed mice through modulation of the renin-angiotensin system. Endocrine. 2015;50:355-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Lehmann JM, Moore LB, Smith-Oliver TA, Wilkison WO, Willson TM, Kliewer SA. An antidiabetic thiazolidinedione is a high affinity ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR gamma). J Biol Chem. 1995;270:12953-12956. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2584] [Cited by in RCA: 2628] [Article Influence: 87.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |