Published online Jul 7, 2023. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v29.i25.4085

Peer-review started: March 23, 2023

First decision: March 28, 2023

Revised: April 1, 2023

Accepted: April 28, 2023

Article in press: April 28, 2023

Published online: July 7, 2023

Processing time: 96 Days and 9.2 Hours

It is estimated that 58 million people worldwide are infected with the hepatitis C virus (HCV). Patients with severe psychiatric disorders could not be treated with previously available interferon-based therapies due to their unfavorable side effect profile. This has changed with the introduction of direct-acting antivirals (DAA), although their real-life tolerance and effectiveness in patients with different psychiatric disorders remain to be demonstrated.

To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of DAA in patients with various mental illnesses.

This was a retrospective observational study encompassing 14272 patients treated with DAA for chronic hepatitis C in 22 Polish hepatology centers, including 942 individuals diagnosed with a mental disorder (anxiety disorder, bipolar affective disorder, depression, anxiety-depressive disorder, personality disorder, schizophrenia, sleep disorder, substance abuse disorder, and mental illness without a specific diagnosis). The safety and effectiveness of DAA in this group were compared to those in a group without psychiatric illness (n = 13330). Antiviral therapy was considered successful if serum ribonucleic acid (RNA) of HCV was undetectable 12 wk after its completion [sustained virologic response (SVR)]. Safety data, including the incidence of adverse events (AEs), serious AEs (SAEs), and deaths, and the frequency of treatment modification and discontinuation, were collected during therapy and up to 12 wk after treatment completion. The entire study population was included in the intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis. Per-protocol (PP) analysis concerned patients who underwent HCV RNA evaluation 12 wk after completing treatment.

Among patients with mental illness, there was a significantly higher percentage of men, treatment-naive patients, obese, human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis B virus-coinfected, patients with cirrhosis, and those infected with genotype 3 (GT3) while infection with GT1b was more frequent in the population without psychiatric disorders. The cure rate calculated PP was not significantly different in the two groups analyzed, with a SVR of 96.9% and 97.7%, respectively. Although patients with bipolar disorder achieved a significantly lower SVR, the multivariate analysis excluded it as an independent predictor of treatment non-response. Male sex, GT3 infection, cirrhosis, and failure of previous therapy were identified as independent negative predictors. The percentage of patients who completed the planned therapy did not differ between groups with and without mental disorders. In six patients, symptoms of mental illness (depression, schizophrenia) worsened, of which two discontinued treatments for this reason. New episodes of sleep disorders occurred significantly more often in patients with mental disorders. Patients with mental illness were more frequently lost to follow-up (4.2% vs 2.5%).

DAA treatment is safe and effective in HCV-infected patients with mental disorders. No specific psychiatric diagnosis lowered the chance of successful antiviral treatment.

Core Tip: In the population of patients with mental illness, the prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection is many times higher than in the general population. In the era of interferon-based therapy, these patients had minimal access to antiviral treatment due to contraindications to interferon with the risk of exacerbation of psychiatric diseases. Their situation has improved with the introduction of direct-acting antivirals, but data from real-world studies are scarce. This retrospective analysis carried out in clinical practice confirmed that the good safety profile and treatment effectiveness are not inferior to those obtained in a population without mental disorders.

- Citation: Dybowska D, Zarębska-Michaluk D, Rzymski P, Berak H, Lorenc B, Sitko M, Dybowski M, Mazur W, Tudrujek-Zdunek M, Janocha-Litwin J, Janczewska E, Klapaczyński J, Parfieniuk-Kowerda A, Piekarska A, Sobala-Szczygieł B, Dobrowolska K, Pawłowska M, Flisiak R. Real-world effectiveness and safety of direct-acting antivirals in hepatitis C virus patients with mental disorders. World J Gastroenterol 2023; 29(25): 4085-4098

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v29/i25/4085.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v29.i25.4085

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, currently affecting approximately 58 million individuals worldwide, still poses a severe global issue[1]. It remains a major cause of chronic liver disease worldwide, liable to progress to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, and can lead to various extrahepatic manifestations[2]. The prevalence of HCV infection is significantly increased (3-fold to 20-fold) in individuals with mental disorders compared to the general population. This includes patients with depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and personality disorders. In patients with substance abuse, particularly with intravenous drug use, the reported percentage of HCV infection is as high as 60%-70%[3,4]. In addition, preexisting mental illness may complicate HCV treatment by adversely affecting treatment adherence[5-7]. Moreover, HCV infection itself can further exacerbate or accelerate psychiatric symptoms[6,8].

In the past, treatment of patients with severe psychiatric disorders infected with HCV was highly challenging due to neuropsychiatric side effects (e.g., anxiety, affective, cognitive, and psychotic symptoms) of previously used interferon (IFN)-based therapies[9]. Their situation has improved with the introduction of direct-acting antivirals (DAA), which are well tolerated and easier to dose[10]. Whether they are also effective in different mental disorders requires further studies. Observations from the IFN-era period indicate that these disorders were not necessarily associated with a worse sustained viral response (SVR) rate[11-13]. However, the observations encompassing the period when DAA were introduced are scarce, include small study groups, only particular diseases (e.g., depression), or treat them collectively as mental disorders[14-17]. The results of one multicenter study evaluating a single DAA regimen among psychiatric patients by type of mental disorder have recently been published, but evidence is still needed from large populations of real-world experience that discriminate between individual psychiatric diseases treated with different DAA options and compare the results to the group without mental disorders while controlling for confounding variables[18].

To this end, the present study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of DAA in patients with various mental illnesses: Anxiety, anxiety-depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, depression, personality disorder, schizophrenia, sleep disorder, substance abuse, and mental illness without a specific diagnosis. In order to achieve this goal, a retrospective, real-world analysis of the Polish population of HCV-infected patients treated with DAA between 2015 and 2022 was conducted.

The data of 14272 patients treated with DAA for chronic hepatitis C (CHC) from 1 July 2015 to 30 December 2022, included in the EpiTer-2 observational study database, were analyzed. This study was conducted under the auspices of the Polish Association of Epidemiologists and Infectiologists and included data from 22 Polish hepatology centers on treating CHC in everyday practice. The choice of CHC therapy was at the physician’s discretion and followed the existing recommendations of the Polish Group of Experts for HCV and the recommendations of the National Health Fund. The data were collected retrospectively and included age, sex, body mass index, the severity of liver disease, HCV genotype (GT), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and/or hepatitis B virus (HBV) coinfection, previous and current CHC treatment, presence of hepatocellular carcinoma, HCV viral load, alanine transaminase activity, albumin, hemoglobin, creatinine, and platelets level.

The patients were divided into two groups: 942 patients with concomitant mental illness (group A) and 13330 without psychiatric disorders (group B). Mentally ill patients were under the care of psychiatrists, who diagnosed their mental illness, prescribed and monitored psychiatric treatment.

The severity of liver disease was assessed using non-invasive methods of fibrosis assessment: Transient elastography or shear-wave elastography with an Aixplorer device (SuperSonic Imagine, Aix-en-Provence, France) or transient FibroScan. Based on the METAVIR score, according to the guidelines of the European Association for the Study of the Liver, the cutoff value of 13 kPa was used to predict individuals considered to be cirrhotic[19]. These patients were evaluated for the presence of decom

Antiviral therapy was considered successful if ribonucleic acid of the virus (HCV RNA) in serum was undetectable 12 wk after its completion, meaning that the patient achieved a sustained virologic response (SVR). Patients with detectable viral load at this time point were considered virologic failures, while those lost to follow-up without HCV RNA evaluation 12 wk after the end of therapy were recognized as non-virological failures and not included in the PP analysis.

An analysis of potential drug-drug interactions was carried out before the start of DAA therapy using an online tool on the University of Liverpool website[20]. The results of this analysis influenced the choice of DAA regimen or modification of psychiatric therapy. Safety data, including the incidence of adverse events (AEs), serious AEs (SEAs), and deaths, as well as the frequency of treatment modification and discontinuation, were collected during therapy and up to 12 wk after treatment completion.

The data were originally collected not for scientific purposes but to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of real-world treatment with registered drugs. Patients were not exposed to any experimental interventions. According to local law (Law of 6 September 2001, Pharmaceutical Law, Article 37al), non-interventional studies do not require ethics committee approval. Due to the retrospective design of the analysis, the requirement for patient consent was not necessary. Patient data were collected and analyzed in accordance with applicable data protection rules.

Statistical analyses were performed using Statistica v. 13 (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK, United States) and MedCalc v. 15.8 (MedCalc Software Ltd, Ostend, Belgium). The entire study population was included in the ITT analysis. The PP analysis concerned patients who underwent HCV RNA evaluation 12 wk after completing treatment. Differences in frequencies of events between groups with and without mental disorders were assessed with χ2 Pearson’s test or Fisher exact test (when the number of observations was < 10). The differences in data expressed on the interval scale were evaluated with a non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test because they did not meet the Gaussian assumption (Shapiro-Wilk’s test, P < 0.05). Multiple logistic regression was used to predict the odds of no response to HCV treatment for mental disorders (for which a lower frequency of SVR was observed) while controlling for known factors affecting the chance of SVR in the IFN and IFN-free era: male sex, obesity, GT3, cirrhosis, history of HCV treatment failure, HIV coinfection, HBV coinfection, and three antiviral combinations: asunaprevir (ASV) and daclatasvir (DCV), sofosbuvir (SOF) and velpatasvir (VEL), and SOF/VEL with ribavirin (RBV)[21-24]. A P value below 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

The demographic characteristics of the groups are summarized in Table 1. Group A included 503 patients who had depression (55.6%), 121 with schizophrenia (12.8%), 36 with mental illness without a specific diagnosis (3.8%), 26 with anxiety-depressive disorders (2.8%), 24 with bipolar affective disorder (2.6%), 21 with anxiety disorders (2.2%), 16 with personality disorders (1.7%), and 6 with sleep disorders (0.6%). Substance abuse disorder was diagnosed in 159 cases (16.9%). Moreover, in 30 patients (3.2%), substance abuse and other mental illness coexisted: Depression in 21 patients (2.2%), personality disorders in 4 (0.4%), schizophrenia in 2 (0.2%), anxiety disorders in 2 (0.2%), and an anxiety-depressive disorder in 1 patient (0.1%).

| Parameter | All patients (n = 14272) | Group A (n = 942) | Group B (n = 13330) | P value | |

| Age, mean (min-max yr) | 51.2 (18-92) | 50.8 (19-90) | 51.2 (18-92) | 0.599 (U = 6216478) | |

| Men/women | 49.3/50.7 (7035/7237) | 54.9/45.1, 507/435 | 49.0/51.0, 6528/6802 | 0.004 (χ2 = 8.3) | |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 26.2 (4.5) | 26.9 (5.1) | 26.1 (4.5) | 0.0001 (U = 5811710) | |

| BMI ≥ 30 | 17.4 (2486) | 23.9 (225) | 17.0 (2261) | < 0.0001 (χ2 = 29.4) | |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Hypertension | 32.0 (4567) | 34.4 (324) | 31.8 (4243) | 0.103 (χ2 = 2.6) | |

| Diabetes | 11.3 (1614) | 13.0 (122) | 11.2 (1492) | 0.100 (χ2 = 0.5) | |

| Renal disease | 3.8 (543) | 3.4 (32) | 3.8 (511) | 0.498 (χ2 = 0.5) | |

| Autoimmune disease | 2.1 (304) | 2.0 (19) | 2.1 (285) | 0.803 (χ2 = 0.06) | |

| Non-HCC tumor | 2.0 (279) | 2.1 (20) | 1.9 (259) | 0.700 (χ2 = 0.15) | |

| ALT (IU/L), median (IQR) | 58.0 (37.0-97.0) | 59.0 (36.0-96.0) | 58.0 (37.0-97.0) | 0.581 (U = 6204221) | |

| Albumin (g/dL), median (IQR) | 4.1 (3.8-4.4) | 4.1 (3.8-4.4) | 4.1 (3.8-4.4) | 0.633 (U = 6222478) | |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL), median (IQR) | 0.6 (0.5-0.9) | 0.6 (0.5-0.9) | 0.6 (0.5-0.9) | 0.060 (U = 6050856) | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL), median (IQR) | 14.5 (13.4-15.5) | 14.4 (13.4-15.4) | 14.5 (13.4-15.6) | 0.307 (U = 6120464) | |

| Platelets (× 1000/μL), median (IQR) | 197.0 (146.0-244.0) | 190.0 (136.0-240.0) | 197.0 (146.0-244.0) | 0.01 (U = 597757) | |

| Creatinine (mg/dL), median (IQR) | 0.8 (0.7-0.9) | 0.8 (0.7-0.9) | 0.8 (0.7-0.9) | 0.798 (U = 6101372) | |

| HCV RNA, × 106 IU/mL, median (IQR) | 0.97 (0.32-2.53) | 1.17 (0.38-3.0) | 0.96 (0.31-2.48) | 0.0005 (U = 5856849) | |

The mean age of patients in both groups was comparable. Group A included a higher percentage of men, obese individuals, patients with more advanced liver fibrosis, and a higher percentage of CP class B and C patients. Similar to group B, the GT1b prevailed, although its frequency was lower, while the higher percentage of HCV-infections with GTs 3 and 4 were noted. Coinfections with HIV and/or HBV were also more common in the group of patients with mental disorders (Table 2).

| Parameters | All patients (n = 14272) | Group A (n = 942) | Group B (n = 13330) | P value |

| Genotype | ||||

| 1a | 4.4 (633) | 4.1 (39) | 4.5 (594) | 0.649 (χ2 = 0.2) |

| 1b | 77.3 (11029) | 67.8 (639) | 77.9 (10390) | < 0.0001 (χ2 = 51.2) |

| 1 | 2.1 (303) | 2.4 (23) | 2.1 (280) | 0.483 (χ2 = 0.5) |

| 2 | 0.2 (29) | 0.2 (2) | 0.2 (27) | > 0.948 (χ2 = 0.004) |

| 3 | 11.1 (1580) | 17.5 (165) | 10.6 (1415) | < 0.0001 (χ2 = 42.6) |

| 4 | 4.9 (695) | 8.0 (74) | 4.7 (621) | < 0.0001 (χ2 = 19.4) |

| 5 | 0.007 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.007 (1) | 1.0 |

| 6 | 0.01 (2) | (0.0) 0 | 0.01 (2) | 1.012 |

| Liver fibrosis | ||||

| F0 | 2.5 (361) | 1.4 (13) | 2.6 (348) | 0.02 (χ2 = 5.4) |

| F1 | 40.8 (5831) | 34.8 (328) | 41.3 (5503) | < 0.0001 (χ2 = 15.2) |

| F2 | 19.2 (2743) | 21.0 (198) | 19.1 (2545) | 0.147 (χ2 = 2.1) |

| F3 | 13.5 (1925) | 13.2 (124) | 13.5 (1801) | 0.763 (χ2 = 0.09) |

| F4 | 23.9 (3412) | 29.6 (279) | 23.5 (3133) | < 0.0001 (χ2 = 18.1) |

| Child-Pugh | ||||

| Child-Pugh-B | 2.8 (398) | 4.4 (41) | 2.7 (357) | 0.003 (χ2 = 9.1) |

| Child-Pugh-C | 0.2 (23) | 0.4 (4) | 0.1 (19) | 0.061 |

| HCC history | 1.3 (191) | 1.2 (11) | 1.3 (180) | 0.637 (χ2 = 0.2) |

| Coinfection | ||||

| HIV | 5.9 (848) | 9.1 (86) | 5.7 (762) | < 0.0001 (χ2 = 18.4) |

| HBV | 13.5 (1933) | 17.5 (165) | 13.3 (1768) | 0.0002 (χ2 = 13.6) |

| HIV/HBV | 1.6 (225) | 3.4 (32) | 1.4 (193) | < 0.0001 (χ2 = 21.6) |

This group was also characterized by a higher baseline HCV viral load. Most patients in group A (80.6%) were treatment-naïve, while 16.7% (n = 157) of the cases had previously been treated with IFN. Of these, 34 patients discontinued IFN-based therapy due to AEs. During current therapy, 12/34 (35%) had mild AEs, the most common of which was headache (n = 3), and one patient in this group experienced increased insomnia. All patients in this group completed therapy as planned, 31 achieved SVR, and 1 patient was lost to follow-up. Patients with mental illnesses were more often treated with pangenotypic therapy for CHC (Table 3).

| Parameter | All patients (n = 14272) | Group A (n = 942) | Group B (n = 13330) | P value |

| History of antiviral treatment | ||||

| Treatment-naïve | 78.7 (11238) | 80.6 (760) | 78.6 (10478) | 0.132 (χ2 = 2.2) |

| Nonresponder to IFN-based regimens | 19.6 (2791) | 16.7 (157) | 19.8 (2634) | 0.02 (χ2 = 5.3) |

| Nonresponder to IFN-free regimens | 1.7 (247) | 2.7 (25) | 1.6 (222) | 0.02 (χ2 = 5.1) |

| Current treatment regimen | ||||

| Pangenotypic regimens | 35.2 (5028) | 43.0 (405) | 34.7 (4619) | < 0.0001 (χ2 = 26.0) |

| Genotype-specific regimens | 64.8 (9248) | 57.0 (537) | 65.3 (8711) | |

| Current-RBV-containing regimens | 16.2 (2308) | 16.5 (155) | 16.1 (2153) | 0.807 (χ2 = 0.05) |

| Genotype-specific treatment regimens | ||||

| ASV + DCV | 0.8 (118) | 1.3 (12) | 0.8 (106) | 0.117 (χ2 = 2.5) |

| SOF/LDV ± RBV | 19.6 (2795) | 21.8 (205) | 19.4 (2590) | 0.081 (χ2 = 3.1) |

| OBV/PTV/r ± DSV ± RBV | 25.4 (3626) | 14.1 (133) | 26.2 (3493) | < 0.0001 (χ2 = 67.8) |

| GZR/EBR ± RBV | 16.8 (2400) | 16.3 (154) | 16.8 (2246) | 0.691 (χ2 = 0.1) |

| Other SOF ± SMV ± DCV ± RBV, SMV ± DCV ± RBV | 2.2 (305) | 3.2 (33) | 2.1 (272) | 0.02 (χ2 = 5.7) |

| Pangenotypic regimens | ||||

| GLE/PIB | 20.6 (2940) | 20.6 (194) | 20.6 (2746) | 0.997 (χ2 = 0.0) |

| GLE/PIB + SOF + RBV | 0.05 (6) | 0.0 (0) | 0.05 (6) | 1.0 |

| SOF/VEL ± RBV | 14.4 (2058) | 22.2 (209) | 13.9 (1849) | < 0.0001 (χ2 = 49.3) |

| SOF/VEL/VOX | 0.2 (24) | 0.2 (2) | 0.2 (22) | 0.670 |

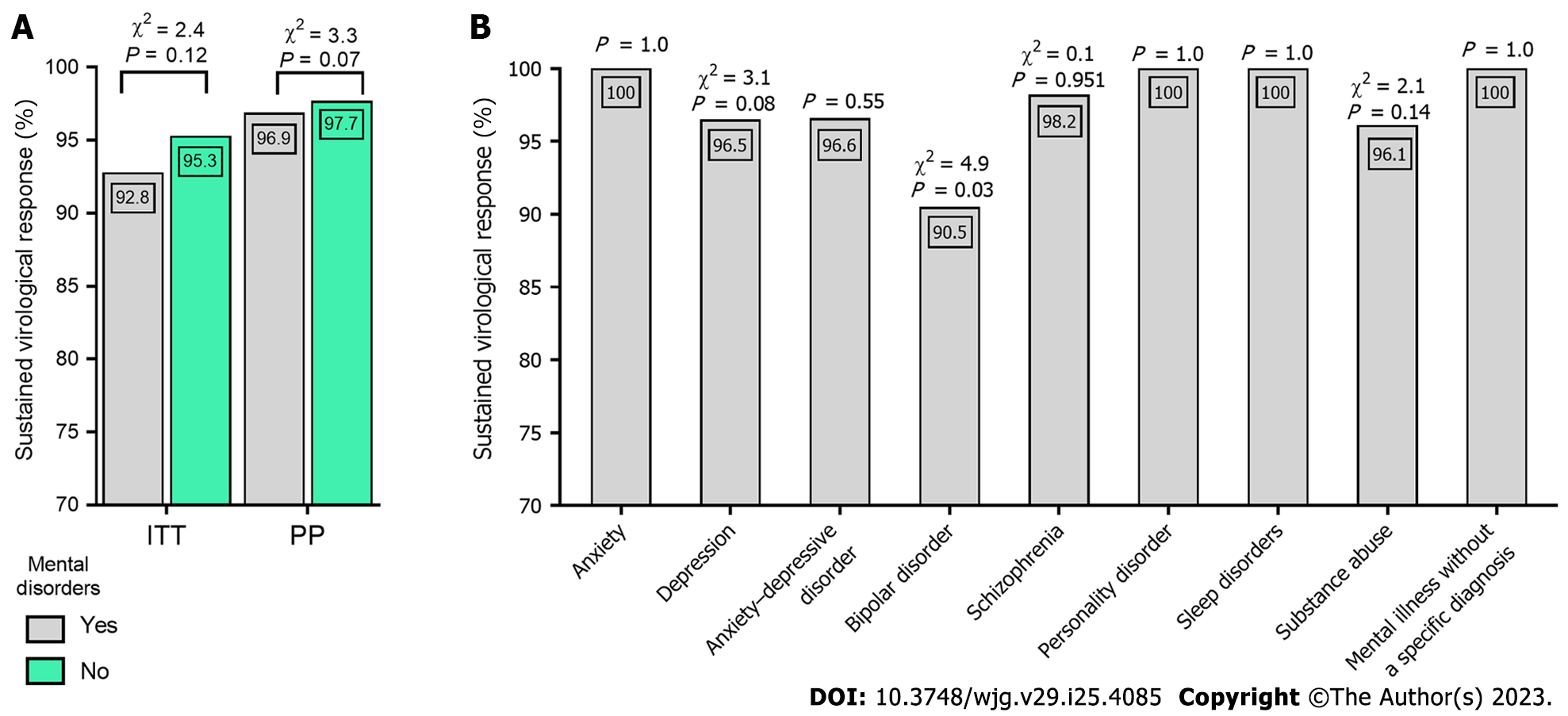

There were no statistically significant differences in the achievement of SVR in groups A and B in both the ITT (92.8% vs 95.3%, respectively) and PP (96.9% vs 97.7%) analyses (Figure 1A). A significantly lower percentage of SVR was observed in patients with bipolar disorder (Figure 1B). In multivariate analyses, a lower chance of SVR was associated with male sex, GT3, cirrhosis, history of previous HCV-treatment failure, and two DAA regimens: ASV + DCV and SOF + VEL + RBV (Table 4).

| Parameter | OR | 95%CI | P value |

| Bipolar disorder | 3.52 | 0.76-16.34 | 0.109 |

| Male sex | 1.93 | 1.51-2.45 | < 0.0001 |

| Obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2) | 1.08 | 0.82-1.43 | 0.579 |

| GT3 | 3.26 | 2.50-4.27 | < 0.0001 |

| Cirrhosis | 2.55 | 2.01-3.22 | < 0.0001 |

| HIV-coinfection | 1.37 | 0.88-2.13 | 0.165 |

| HBV-coinfection | 0.85 | 0.61-1.18 | 0.323 |

| History of HCV-treatment failure | 1.46 | 1.14-1.87 | 0.003 |

| ASV+DCV | 4.97 | 2.60-9.55 | < 0.0001 |

| SOF/VEL | 0.86 | 0.61-1.20 | 0.371 |

| SOF/VEL+RBV | 2.37 | 1.34-4.17 | 0.003 |

Patients with mental illness more often belonged to the group lost to follow-up (4.2% vs 2.5%). In six patients symptoms of mental illness (depression - 5, schizophrenia - 1) worsened during antiviral therapy, of which two permanently discontinued treatment for this reason. New episodes of sleep disorders occurred significantly more often in group A during DAA therapy. In group B, one patient experienced an episode of schizophrenia, and six were diagnosed with depression. In both groups, a similar percentage of patients completed the planned treatment. There were no statistically significant differences in discontinued and modified treatments (Table 5).

| Parameter | All patients (n = 14272) | Group A (n = 942) | Group B (n = 13330) | P value |

| Treatment course | ||||

| According to schedule | 97.5 (13848) | 96.8 (907) | 97.6 (12941) | 0.164 (χ2 = 1.9) |

| Therapy discontinuation | 1.1 (157) | 1.4 (13) | 1.1 (144) | 0.394 (χ2 = 0.7) |

| Therapy modification | 1.4 (194) | 1.8 (17) | 1.3 (177) | 0.222 (χ2 = 1.5) |

| No data | 0.5 (73) | 0.5 (5) | 0.5 (68) | 0.813 |

| Death | 0.5 (71) | 0.4 (4) | 0.5 (67) | 1.0 |

| SAE | 1.0 (145) | 1.6 (15) | 0.97 (130) | 0.068 (χ2 = 3.3) |

| Psychiatric complications | ||||

| New incidence of depression | 0.1 (8) | 0.2 (2) | 0.05 (6) | 0.093 |

| New incidence of schizophrenia | 0.0 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (1) | 1.0 |

| New incidence of sleep disorders | 1.8 (262) | 3.3 (31) | 1.7 (231) | 0.001 (χ2 = 10.4) |

| New incidence of anxiety | 0.0 (1) | 0.1 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 1.0 |

| Drinking binge | 0.0 (1) | 0.1 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 1.0 |

| Exacerbation of psychiatric disease | 0.6 (6) | |||

| Depression | 0.5 (5) | |||

| Schizophrenia | 0.1 (1) |

Modification of therapy concerned only a change in the dose of RBV. Possible drug interactions were analyzed prior to antiviral therapy. Patients in group A were treated with neuroleptics, anticonvulsants, antidepressants, sedatives, anxiolytics, and methadone. Only carbamazepine could have clinically relevant interactions. This drug was used in 3 patients in group A and in 12 patients in group B. All patients with mental diseases using carbamazepine completed the treatment as planned without AEs, and all achieved SVR.

By documenting the high rate of SVR in patients with mental diseases, our study proves that this patient population does not differ in their response to DAA treatment from those with CHC not affected by psychiatric conditions supporting the findings of a recently published multicenter analysis[18]. Thus, there is no rationale for considering these patients as a difficult-to-treat population in terms of virologic response to therapy, as they were previously recognized in the era of IFN-based regimens. Antiviral therapy for mentally ill patients has been a challenge due to contraindications to the use of IFN and the side effects of this cytokine[9,25]. Neuropsychiatric disorders of various caliber during IFN therapy have been widely reported[26-28]. Most were mild in severity and transient in nature, but severe psychosis and suicide attempts have also been described as a reason for discontinuing therapy. Such side effects of therapy have been described even in patients with no prior mental disorders[29]. Due to the risk of exacerbating psychiatric conditions, many patients with a diagnosed mental illness were not eligible for treatment. The mental state of those included in therapy had to be closely monitored, requiring cooperation with the patient’s attending psychiatrist[30]. This was the only way to keep the patient in therapy and in the event of exacerbation of mental disorders, to react swiftly and to modify or discontinue antiviral treatment, if necessary for safety reasons[5,31]. At the same time, this was a population of patients in whom successful antiviral therapy offered a chance for mental improvement[32]. In addition to causing liver disease, HCV can potentially induce extrahepatic manifestations, i.e., disorders of other organs and systems that are pathogenetically associated with infection[33]. One of them is the central nervous system, whose involvement results in neurological and psychiatric disorders[6,7,34]. The mechanism of the virus’s impact on the nervous system is complex and includes both a direct cytopathic effect related to the infection of nerve cells, as well as the impact of the immune response triggered by the HCV and the effects of psychogenic stressors[8,34,35].

The frequent co-occurrence of CHC and psychiatric disorders was confirmed by numerous studies analyzing this issue in Real World Evidence (RWE) populations[36,37]. The estimated frequency of active mental illness in patients with CHC assessed in the large cohort of American Veterans was as high as one-third, while in our analysis, the percentage of patients was 6.6%[38]. Among them, depression, addiction, and schizophrenia were the most common. On the other hand, the pooled prevalence of HCV infection among patients with severe psychiatric diseases evaluated in a meta-analysis that included papers from 1989-2020 was 8%, which is several times higher compared to the general population[38,39]. However, the fact that patients with mental illnesses are disproportionately affected by HCV is also influenced by other factors beyond the pathogenetic relationship. One that seems to be historical is exposure to infection through frequent contact with healthcare facilities, and it cannot be overlooked that hospitalizations for mental illness are very long. Another factor contributing to the higher prevalence of HCV infections in this population, the importance of which persists to the present day, is that persons diagnosed with mental disorders are much more likely to abuse substances, including injection drugs and needle sharing used for intravenous drug administration is the most common route of HCV transmission[17]. This was also documented in our analysis. Moreover, the population of HCV-infected patients with mental diseases, which was underserved in the era of IFN, has gained its opportunity in the time of DAA therapy. The much shorter course of treatment and the lack of contraindications to the drugs has enabled patients with psychiatric disorders to access therapy on the same principles as for other HCV-infected individuals and has provided a basis for predicting HCV microelimination in this population[18]. In the current analysis, we found no statistically significant differences in the course of treatment in mentally ill patients compared to others. The percentage of those who had their therapy modified or discontinued was comparable; the modification in both groups concerned only RBV dose reduction according to the label. The safety profile was also comparable with the percentage of patients experiencing SEAs and deaths. Similar conclusions on the good tolerability of DAA can be drawn from the observations of other researchers in RWE cohorts[40,41]. When analyzing psychiatric complications occurring during therapy, we found a significantly higher percentage of sleep disorders in patients with psychiatric diseases than in those without mental conditions. Other researchers evaluating the quality of sleep in patients with mental disorders did not find any significant differences during DAA therapy compared to the baseline, demonstrating that DAA regimens are free of mental side effects regardless of current and/or past psychiatric history[14,15].

In our analysis, however, in six patients, the underlying disease (five cases of depression and one of schizophrenia) worsened during antiviral therapy, which in 2 cases was the reason for discontinuing treatment. However, we cannot exclude the potential influence of other factors. It should be noted that the cited analyses were prospective, while ours is a retrospective study with limitations in data collection. Interestingly, another prospective study reported some degree of neuropsychiatric impairment associated with IFN-free treatment in 10 cirrhotic patients, suggesting their susceptibility to mild DAA neurotoxicity[42].

Despite the significant change in access to treatment, there are still some challenges for a group of patients with mental illness. These are related to potential drug interactions. For this reason, this is carefully reviewed before therapy, and if there are contraindications to combining medications, psychiatric drugs are modified to allow the patient to receive antiviral treatment. This is not always possible; in our study, three patients were on carbamazepine, which could not be discontinued as it was the only drug that stabilized their mental state. Although this drug is not recommended in combination with DAA because it can reduce their levels below therapeutic levels, all patients completed the treatment as planned without AEs and achieved SVR. It should be emphasized that a possible modification in psychiatric treatment in case of expected drug interactions, as well as monitoring the mental state of the patient, requires the cooperation of a hepatologist and a psychiatrist. However, the scope of supervision is significantly smaller than in the case of IFN-based therapy[17,43]. The issue we highlighted in our analysis was the significantly higher percentage of patients lost to follow-up without SVR evaluation in the population of patients with mental illness compared to those without mental disorders, 4.2% vs 2.5%, respectively. The problem with adherence, concerning not only the use of drugs which was not evaluated in our study but, as in this case, keeping the dates of follow-up visits, is also raised by other authors[18]. However, some analyses did not report the difference in adherence between mentally ill patients (including those with substance abuse disorder) and the general HCV-infected population[3,40,44].

In patients with available SVR, we did not observe significant differences in the effectiveness of DAA therapy depending on the diagnosis of mental illness, which is consistent with reports from other RWE cohorts[40,45]. A 96.9% cure rate was achieved in the mentally affected group compared to 97.7% in the patients without psychiatric disorders, despite a higher proportion of men, those with liver cirrhosis, and a higher prevalence of GT3 infection in this population, which are considered negative predictors of SVR in HCV-infected patients treated with DAA[21]. Significantly lower SVR rates have been documented in patients with bipolar disorder, which is consistent with the results of the analysis by Wedemeyer et al[18]. However, this multicenter study did not control for potential confounders, while in our research, the multivariate analysis clearly excluded bipolar disorder as an independent predictor of non-response to treatment. The identified independent negative predictors included the presence of liver cirrhosis, GT3 infection, history of prior therapy failure, and male gender, which is in line with available data concerning the general HCV-infected population[21,46]. However, apart from the abovementioned factors, administration of the ASV + DCV regimen or SOF/(VEL + RBV) combination was also associated with a lower chance of SVR. The ASV + DCV option was registered only for patients with GT1b infection and used until 2018. Due to its cumulative efficacy of 85%, evaluated in a meta-analysis of 9 clinical trials, it was considered suboptimal[23]. The SOF/(VEL + RBV) regimen is registered in patients with decompensated cirrhosis, and its efficacy in a randomized clinical trial was 83%[47]. In our analysis, 23/26 (88.5%) patients with mental disorders responded to this type of treatment. There are no papers evaluating this regimen exclusively in patients with mental illness, so we cannot relate our results to another study.

Our study has some limitations which we wish to stress. This is a retrospective study with all its consequences, such as incomplete data, including information on side effects, data entry errors, and possible bias. The database includes information from baseline to 12 wk after the end of therapy, and there are no data on the number of patients who had their psychiatric treatment modified before treatment, as well as the nature of these modifications. Additionally, no data were collected on the adjustment of psychiatric treatment during DAA therapy. Another limitation is the lack of systematic monitoring of the patient’s mental state, such as with appropriate questionnaires. The main strength of the current study is the large group of patients from different centers in our country treated in routine clinical practice, which affects the quality of the results and the possibility of generalizing conclusions. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to address the problem of treating CHC with various DAA regimens in patients with mental disorders, highlighting the differences in specific psychiatric illnesses.

This study provides real-world evidence for the effectiveness and safety of DAA treatment of HCV infection in patients with preexisting psychiatric disorders. As shown, most of these patients achieve SVR. No specific psychiatric diagnosis lowered the chance of successful DAA treatment. Negative predictors of virologic response do not differ for these patients compared to the general HCV-infected population and include cirrhosis, GT3 infection, male gender, and failure of previous therapy.

In the era of interferon (IFN)-based therapies, patients with psychiatric disorders had limited access to therapy due to their unfavorable safety profile. This changed with the introduction of direct-acting antiviral (DAA) drugs.

We aimed to evaluate the tolerability and effectiveness of IFN-free therapies in patients with various psychiatric disorders and to identify predictors of virologic response in this patient population.

Data of 14272 patients treated with IFN-free regimens for chronic hepatitis C included in the EpiTer-2 database were analyzed. The patients were divided into two groups: 942 patients with mental disorders and 13330 without psychiatric diseases.

The effectiveness and safety of antiviral treatment were compared between both populations. Effectiveness was assessed by the percentage of patients with sustained virologic response (SVR). Multiple logistic regression was used to predict the odds of no SVR in patients with mental illness. Safety data were collected through the treatment period and 12 wk of follow-up.

The cure rate was not significantly different in the two groups analyzed, with an SVR of 96.9% in patients with psychiatric disorders and 97.7% without psychiatric disorders. Patients with bipolar disorder achieved a lower SVR (90.5%), but multivariate analysis excluded it as an independent predictor of treatment non-response. Male gender, genotype 3 infection, cirrhosis and failure of previous therapy were identified as independent negative predictors. The percentage of patients who completed the planned therapy did not differ between the groups with and without mental disorders. In six patients, symptoms of mental illness (depression, schizophrenia) worsened, of which two discontinued treatment for this reason. New episodes of sleep disorders occurred significantly more often in patients with mental disorders. Patients with mental illness were more frequently lost to follow-up (4.2% vs 2.5%).

DAA treatment is safe and effective in hepatitis C virus (HCV)-infected patients with mental disorders. No specific psychiatric diagnosis lowered the chance of successful antiviral treatment.

The data obtained provide real-world evidence of the effectiveness and safety of DAA for HCV infection in patients with mental disorders, indicating that there are no differences compared with the general HCV-infected population.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author’s Membership in Professional Societies: Polish Association of Hepatology; Polish Society of Epidemiologists and Infectiologists.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Poland

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Isakov V, Russia; Liu CH, Taiwan S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Zhao S

| 1. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Global Viral Hepatitis: Millions of People are Affected. [cited 8 March 2023]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/global/index.htm. |

| 2. | Lavanchy D. Evolving epidemiology of hepatitis C virus. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:107-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 919] [Cited by in RCA: 945] [Article Influence: 67.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Gutiérrez-Rojas L, de la Gándara Martín JJ, García Buey L, Uriz Otano JI, Mena Á, Roncero C. Patients with severe mental illness and hepatitis C virus infection benefit from new pangenotypic direct-acting antivirals: Results of a literature review. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;46:382-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Roncero C, Littlewood R, Vega P, Martinez-Raga J, Torrens M. Chronic hepatitis C and individuals with a history of injecting drugs in Spain: population assessment, challenges for successful treatment. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29:629-633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rifai MA, Gleason OC, Sabouni D. Psychiatric care of the patient with hepatitis C: a review of the literature. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Faccioli J, Nardelli S, Gioia S, Riggio O, Ridola L. Neurological and psychiatric effects of hepatitis C virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:4846-4861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 7. | Adinolfi LE, Nevola R, Lus G, Restivo L, Guerrera B, Romano C, Zampino R, Rinaldi L, Sellitto A, Giordano M, Marrone A. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection and neurological and psychiatric disorders: an overview. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:2269-2280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Mathew S, Faheem M, Ibrahim SM, Iqbal W, Rauff B, Fatima K, Qadri I. Hepatitis C virus and neurological damage. World J Hepatol. 2016;8:545-556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Davoodi L, Masoum B, Moosazadeh M, Jafarpour H, Haghshenas MR, Mousavi T. Psychiatric side effects of pegylated interferon-α and ribavirin therapy in Iranian patients with chronic hepatitis C: A meta-analysis. Exp Ther Med. 2018;16:971-978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | McGlynn EA, Adams JL, Kramer J, Sahota AK, Silverberg MJ, Shenkman E, Nelson DR. Assessing the Safety of Direct-Acting Antiviral Agents for Hepatitis C. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e194765. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Niederau C, Mauss S, Schober A, Stoehr A, Zimmermann T, Waizmann M, Moog G, Pape S, Weber B, Isernhagen K, Sandow P, Bokemeyer B, Alshuth U, Steffens H, Hüppe D. Predictive factors for sustained virological response after treatment with pegylated interferon α-2a and ribavirin in patients infected with HCV genotypes 2 and 3. PLoS One. 2014;9:e107592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Schäfer A, Scheurlen M, Weissbrich B, Schöttker K, Kraus MR. Sustained virological response in the antiviral therapy of chronic hepatitis C: is there a predictive value of interferon-induced depression? Chemotherapy. 2007;53:292-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Elsherif O, Bannan C, Keating S, McKiernan S, Bergin C, Norris S. Outcomes from a large 10 year hepatitis C treatment programme in people who inject drugs: No effect of recent or former injecting drug use on treatment adherence or therapeutic response. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0178398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fabrazzo M, Zampino R, Vitrone M, Sampogna G, Del Gaudio L, Nunziata D, Agnese S, Santagata A, Durante-Mangoni E, Fiorillo A. Effects of Direct-Acting Antiviral Agents on the Mental Health of Patients with Chronic Hepatitis C: A Prospective Observational Study. Brain Sci. 2020;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sundberg I, Lannergård A, Ramklint M, Cunningham JL. Direct-acting antiviral treatment in real world patients with hepatitis C not associated with psychiatric side effects: a prospective observational study. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18:157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Janjua NZ, Wong S, Darvishian M, Butt ZA, Yu A, Binka M, Alvarez M, Woods R, Yoshida EM, Ramji A, Feld J, Krajden M. The impact of SVR from direct-acting antiviral- and interferon-based treatments for HCV on hepatocellular carcinoma risk. J Viral Hepat. 2020;27:781-793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sockalingam S, Sheehan K, Feld JJ, Shah H. Psychiatric care during hepatitis C treatment: the changing role of psychiatrists in the era of direct-acting antivirals. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172:512-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wedemeyer H, Di Marco V, Garcia-Retortillo M, Teti E, Fraser C, Morano Amado LE, Rodriguez-Tajes S, Acosta-López S, O'Loan J, Milella M, Buti M, Guerra-Veloz MF, Ramji A, Fenech M, Martins A, Borgia SM, Vanstraelen K, Mertens M, Hernández C, Ntalla I, Ramroth H, Milligan S. Global Real-World Evidence of Sofosbuvir/Velpatasvir as a Highly Effective Treatment and Elimination Tool in People with Hepatitis C Infection Experiencing Mental Health Disorders. Viruses. 2022;14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. Clinical Practice Guidelines Panel: Chair:; EASL Governing Board representative:; Panel members:. EASL recommendations on treatment of hepatitis C: Final update of the series(☆). J Hepatol. 2020;73:1170-1218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 567] [Cited by in RCA: 779] [Article Influence: 155.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | University of Liverpool. Liverpool HEP Interactions. [cited 8 March 2023]. Available from: https://www.hep-druginteractions.org/. |

| 21. | Pabjan P, Brzdęk M, Chrapek M, Dziedzic K, Dobrowolska K, Paluch K, Garbat A, Błoniarczyk P, Reczko K, Stępień P, Zarębska-Michaluk D. Are There Still Difficult-to-Treat Patients with Chronic Hepatitis C in the Era of Direct-Acting Antivirals? Viruses. 2022;14:96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Brzdęk M, Zarębska-Michaluk D, Rzymski P, Lorenc B, Kazek A, Tudrujek-Zdunek M, Janocha-Litwin J, Mazur W, Dybowska D, Berak H, Parfieniuk-Kowerda A, Klapaczyński J, Sitko M, Sobala-Szczygieł B, Piekarska A, Flisiak R. Changes in characteristics of patients with hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis from the beginning of the interferon-free era. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29:2015-2033. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Nguyen Thi Thu P, Ngo Thi Quynh M, Pham Van L, Nguyen Van H, Nguyen Thanh H. Determination of Risk Factors Associated with the Failure of 12 Weeks of Direct-Acting Antiviral Therapy in Patients with Hepatitis C: A Prospective Study. Biomed Res Int. 2022;2022:6054677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Xie J, Xu B, Wei L, Huang C, Liu W. Effectiveness and Safety of Sofosbuvir/Velpatasvir/Voxilaprevir as a Hepatitis C Virus Infection Salvage Therapy in the Real World: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Infect Dis Ther. 2022;11:1661-1682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ho SB, Nguyen H, Tetrick LL, Opitz GA, Basara ML, Dieperink E. Influence of psychiatric diagnoses on interferon-alpha treatment for chronic hepatitis C in a veteran population. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:157-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Trask PC, Esper P, Riba M, Redman B. Psychiatric side effects of interferon therapy: prevalence, proposed mechanisms, and future directions. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2316-2326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Juszczyk J, Baka-Cwierz B, Beniowski M, Berak H, Bolewska B, Boroń-Kaczmarska A, Cianciara J, Cieśla A, Dziambor A, Gasiorowski J, Gietka A, Gliwińska E, Gładysz A, Gonciarz Z, Halota W, Horban A, Inglot M, Janas-Skulina U, Janczewska-Kazek E, Jaskowska J, Jurczyk K, Knysz B, Kryczka W, Kuydowicz J, Lakomy EA, Logiewa-Bazger B, Lyczak A, Mach T, Mazur W, Michalska Z, Modrzewska R, Nazzal K, Pabjan P, Piekarska A, Piszko P, Sikorska K, Szamotulska K, Sliwińska M, Swietek K, Tomasiewicz K, Topczewska-Staubach E, Trocha H, Wasilewski M, Wawrzynowicz-Syczewska M, Wrodycki W, Zarebska-Michaluk D, Zejc-Bajsarowicz M. [Pegylated interferon-alfa 2a with ribavirin in chronic viral hepatitis C (final report)]. Przegl Epidemiol. 2005;59:651-660. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Raison CL, Borisov AS, Broadwell SD, Capuron L, Woolwine BJ, Jacobson IM, Nemeroff CB, Miller AH. Depression during pegylated interferon-alpha plus ribavirin therapy: prevalence and prediction. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:41-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Drozdz W, Borkowska A, Wilkosc M, Halota W, Dybowska D, Rybakowski JK. Chronic paranoid psychosis and dementia following interferon-alpha treatment of hepatitis C: a case report. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2007;40:146-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Lotrich F. Management of Psychiatric Disease in Hepatitis C Treatment Candidates. Curr Hepat Rep. 2010;9:113-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Quelhas R, Lopes A. Psychiatric problems in patients infected with hepatitis C before and during antiviral treatment with interferon-alpha: a review. J Psychiatr Pract. 2009;15:262-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Goñi Esarte S, Juanbeltz R, Martínez-Baz I, Castilla J, San Miguel R, Herrero JI, Zozaya JM. Long-term changes on health-related quality of life in patients with chronic hepatitis C after viral clearance with direct-acting antiviral agents. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2019;111:445-452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Zarebska-Michaluk DA, Lebensztejn DM, Kryczka WM, Skiba E. Extrahepatic manifestations associated with chronic hepatitis C infections in Poland. Adv Med Sci. 2010;55:67-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Yarlott L, Heald E, Forton D. Hepatitis C virus infection, and neurological and psychiatric disorders - A review. J Adv Res. 2017;8:139-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Więdłocha M, Marcinowicz P, Sokalla D, Stańczykiewicz B. The neuropsychiatric aspect of the HCV infection. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2017;26:167-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Perry W, Hilsabeck RC, Hassanein TI. Cognitive dysfunction in chronic hepatitis C: a review. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:307-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Butt AA, Khan UA, McGinnis KA, Skanderson M, Kent Kwoh C. Co-morbid medical and psychiatric illness and substance abuse in HCV-infected and uninfected veterans. J Viral Hepat. 2007;14:890-896. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | el-Serag HB, Kunik M, Richardson P, Rabeneck L. Psychiatric disorders among veterans with hepatitis C infection. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:476-482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Braude MR, Phan T, Dev A, Sievert W. Determinants of Hepatitis C Virus Prevalence in People With Serious Mental Illness: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2021;83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Fiore V, De Vito A, Colpani A, Manca V, Maida I, Madeddu G, Babudieri S. Viral Hepatitis C New Microelimination Pathways Objective: Psychiatric Communities HCV Free. Life (Basel). 2022;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | de Gennaro N, Diella L, Monno L, Angarano G, Milella M, Saracino A. Efficacy and tolerability of DAAs in HCV-monoinfected and HCV/HIV-coinfected patients with psychiatric disorders. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20:196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Volpato S, Montagnese S, Zanetto A, Turco M, De Rui M, Ferrarese A, Amodio P, Germani G, Senzolo M, Gambato M, Russo FP, Burra P. Neuropsychiatric performance and treatment of hepatitis C with direct-acting antivirals: a prospective study. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2017;4:e000183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Chasser Y, Kim AY, Freudenreich O. Hepatitis C Treatment: Clinical Issues for Psychiatrists in the Post-Interferon Era. Psychosomatics. 2017;58:1-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2101-2107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2682] [Cited by in RCA: 2745] [Article Influence: 109.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Back D, Belperio P, Bondin M, Negro F, Talal AH, Park C, Zhang Z, Pinsky B, Crown E, Mensa FJ, Marra F. Efficacy and safety of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir in patients with chronic HCV infection and psychiatric disorders: An integrated analysis. J Viral Hepat. 2019;26:951-960. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Wang HL, Lu X, Yang X, Xu N. Effectiveness and safety of daclatasvir plus asunaprevir for hepatitis C virus genotype 1b: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32:45-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Curry MP, O'Leary JG, Bzowej N, Muir AJ, Korenblat KM, Fenkel JM, Reddy KR, Lawitz E, Flamm SL, Schiano T, Teperman L, Fontana R, Schiff E, Fried M, Doehle B, An D, McNally J, Osinusi A, Brainard DM, McHutchison JG, Brown RS Jr, Charlton M; ASTRAL-4 Investigators. Sofosbuvir and Velpatasvir for HCV in Patients with Decompensated Cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2618-2628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 599] [Cited by in RCA: 613] [Article Influence: 61.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |