Published online May 21, 2023. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v29.i19.3040

Peer-review started: March 14, 2023

First decision: April 10, 2023

Revised: April 17, 2023

Accepted: April 25, 2023

Article in press: April 25, 2023

Published online: May 21, 2023

Processing time: 62 Days and 18.2 Hours

Hepatitis C infection not only damages the liver but also often accompanies many extrahepatic manifestations. Incidences of pulmonary hypertension (PH) caused by hepatitis C are rare, and incidences of concurrent nephrotic syndrome and polymyositis are even rarer.

Herein we describe the case of a 57-year-old woman who was admitted to our department for intermittent chest tightness upon exertion for 5 years, aggravated with dyspnea for 10 d. After relevant examinations she was diagnosed with PH, nephrotic syndrome, and polymyositis due to chronic hepatitis C infection. A multi-disciplinary recommendation was that the patient should be treated with sildenafil and macitentan in combination and methylprednisolone. During treatment autoimmune symptoms, liver function, hepatitis C RNA levels, and cardiac parameters of right heart catheterization were monitored closely. The patient showed significant improvement in 6-min walking distance from 100 to 300 m at 3-mo follow-up and pulmonary artery pressure drops to 50 mmHg. Long-term follow-up is needed to confirm further efficacy and safety.

Increasing evidence supports a relationship between hepatitis C infection and diverse extrahepatic manifestations, but it is very rare to have PH, nephrotic syndrome, and polymyositis in a single patient. We conducted a literature review on the management of several specific extrahepatic manifestations of hepatitis C.

Core Tip: Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection should be considered a systemic disease which is often associated with many extrahepatic manifestations, but it is very rare to have multiple different extrahepatic manifestations in a single patient. In this article, we report a case of pulmonary hypertension (PH), nephrotic syndrome, and polymyositis due to HCV infection. The optimal treatment strategy for hepatitis C-related extrahepatic manifestations remains to be determined. Our case confirms sildenafil and macitentan as effective treatment option for patients suffering from PH due to hepatitis C infection. However, randomized, controlled trials are warranted to confirm the present results.

- Citation: Zhao YN, Liu GH, Wang C, Zhang YX, Yang P, Yu M. Pulmonary hypertension, nephrotic syndrome, and polymyositis due to hepatitis C virus infection: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2023; 29(19): 3040-3047

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v29/i19/3040.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v29.i19.3040

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a sporadic and a common cause of chronic hepatitis after blood transfusion. In recent years various authors have described associations between hepatitis C infection and a heterogeneous group of non-hepatic diseases such as cryoglobulinemia, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjogren’s syndrome, and glomerulonephritis, which are seen as extrahepatic manifestations of chronic hepatitis C infection[1].

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is defined as a mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP) ≥ 20 mmHg at rest with right heart catheterization[2]. PH affects approximately 1% of the global population, up to 10% of individuals aged ≥ 65 years, and at least 50% of patients with heart failure[3]. PH has several different causes with different management and outcomes. However, PH due to hepatitis C has rarely been reported. Herein we describe a case of PH, nephrotic syndrome, and polymyositis following chronic hepatitis C infection in a 57-year-old woman.

A 57-year-old Chinese woman presenting with untreated chest tightness, shortness of breath, and fatigue for 5 years and with dyspnea for 10 d was admitted to the China-Japan Union Hospital of Jilin University.

She had no precordial pain, orthopnea, or palpitation. She had no joint pain, dental ulcers, or rash.

Forty years previously she had received an intravenous blood transfusion for a right ovariectomy. Sixteen years previously she was diagnosed with hepatitis C, nephrotic syndrome, and hypertension, but did not receive standard treatment. Five years previously she developed mild PH with pulmonary arterial pressure of 54 mmHg measured by transthoracic echocardiography, which was not treated further. Three years previously she developed severe myopathy. She was diagnosed with polymyositis and administered methylprednisolone 40 mg once a day (QD) and cyclophosphamide 50 mg QD. She lapsed into intermittent coma due to hyperemic ammonia however, thus cyclophosphamide was discontinued, and methylprednisolone 20 mg QD was initiated and has been maintained to date.

She had no family history of genetically related diseases, but her daughter had hepatitis C and had been treated with interferon.

Physical examination revealed no fever, heart rate 70 bpm, blood pressure 140/90 mmHg, O2 saturation 94% on room air, second heart sound accentuation, and moderate edema in both lower limbs.

Primary laboratory data on admission are shown in Table 1. The 6-min walking distance was 100 m.

| Parameter | Value (admission) | Value (month 1) | References value | Unit |

| N-terminal-pro B-type natriuretic peptide | 590 | 0-125 | pg/mL | |

| Urea | 10.02 | 11.6 | 2.5-6.1 | mmol/L |

| Creatinine | 123.4 | 124.9 | 46-92 | μmol/L |

| Troponin | < 0.01 | 0-0.04 | ng/mL | |

| Myoglobin | 208.1 | 0-120 | ng/mL | |

| Creatine kinase | 576.24 | 98.6 | 30-135 | U/L |

| Creatine kinase MB isoenzyme | 42.1 | 50.2 | 0-16 | U/L |

| Lactic dehydrogenase | 378.88 | 777.2 | 120-246 | U/L |

| D-dimer | 1.28 | 0-0.5 | μg/mL | |

| White blood cell | 9.10 | 14.05 | 4-10 | 109/L |

| Platelet | 140 | 111 | 125-350 | 109/L |

| Hemoglobin | 119 | 152 | 110-150 | g/L |

| Alanine aminotransferase | 18.28 | 41.4 | 5-40 | IU/L |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 15.44 | 16.1 | 8-40 | IU/L |

| Total bilirubin | 16.48 | 30.10 | 5-21 | μmol/L |

| Direct bilirubin | 3.36 | 7.40 | 0-3.4 | μmol/L |

| Indirect bilirubin | 13.12 | 22.70 | 1.6-21 | μmol/L |

| Albumin | 22.73 | 25.65 | 35-52 | g/L |

| Total cholesterol | 7.67 | 3.0-5.7 | mmol/L | |

| Low density lipoprotein cholesterol | 3.65 | < 4.13 | mmol/L | |

| High density lipoprotein cholesterol | 2.86 | 1.29-1.55 | mmol/L | |

| Fasting blood glucose | 4.44 | 3.9-6.1 | Mmol/L | |

| Urinary protein | 4+ | negative | - | |

| 24-h proteinuria | 416.01 | 0-150 | mg/d | |

| Hepatitis B surface antigen | 0 | < 0.05 | IU/mL | |

| Antibody to hepatitis C | 6.04 | < 1 | S/CO | |

| Immunodeficiency virus antigen and antibody | 0.09 | < 1 | S/CO | |

| Antibody to treponema pallidum | 0.07 | < 1 | S/CO | |

| Hepatitis C virus RNA | 0 | 0 | IU/mL | |

| Anti-nuclear antibodies | negative | negative | - | |

| Anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody | 13.89 | < 25 | RU/mL | |

| Anti-cardiolipin antibody | 2.23 | 0-12 | RU/mL | |

| Immunoglobulin G | 4.92 | 7.51-15.60 | g/L | |

| Immunoglobulin A | 2.82 | 0.82-4.53 | g/L | |

| Immunoglobulin M | 1.81 | 0.46-3.04 | g/L | |

| C3 | 0.58 | 0.79-1.52 | g/L | |

| C4 | 0.14 | 0.16-0.38 | g/L | |

| Blood ammonia | 56 | 9-30 | μmol/L | |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | 22 | 6 | 0-20 | mm/h |

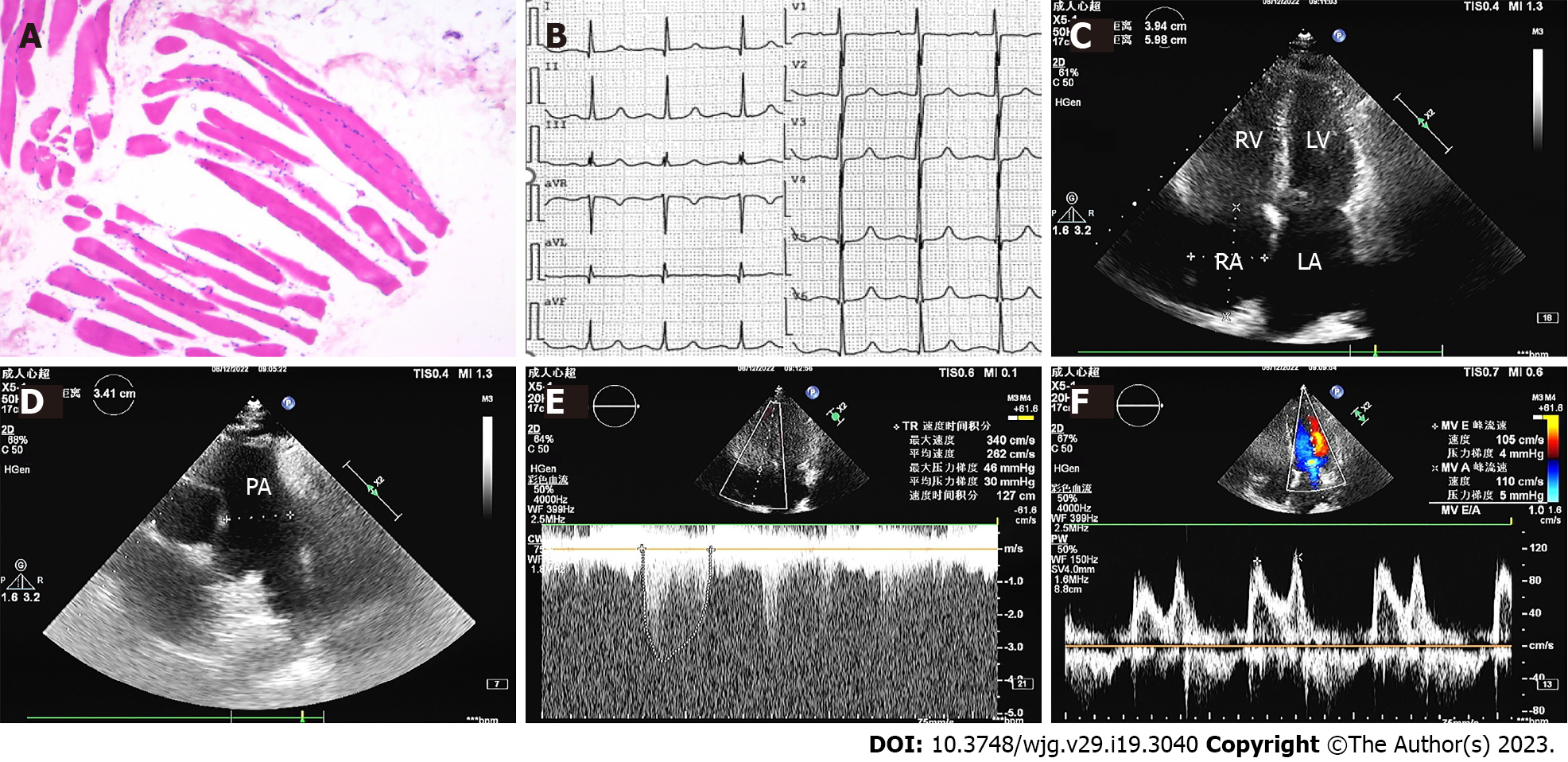

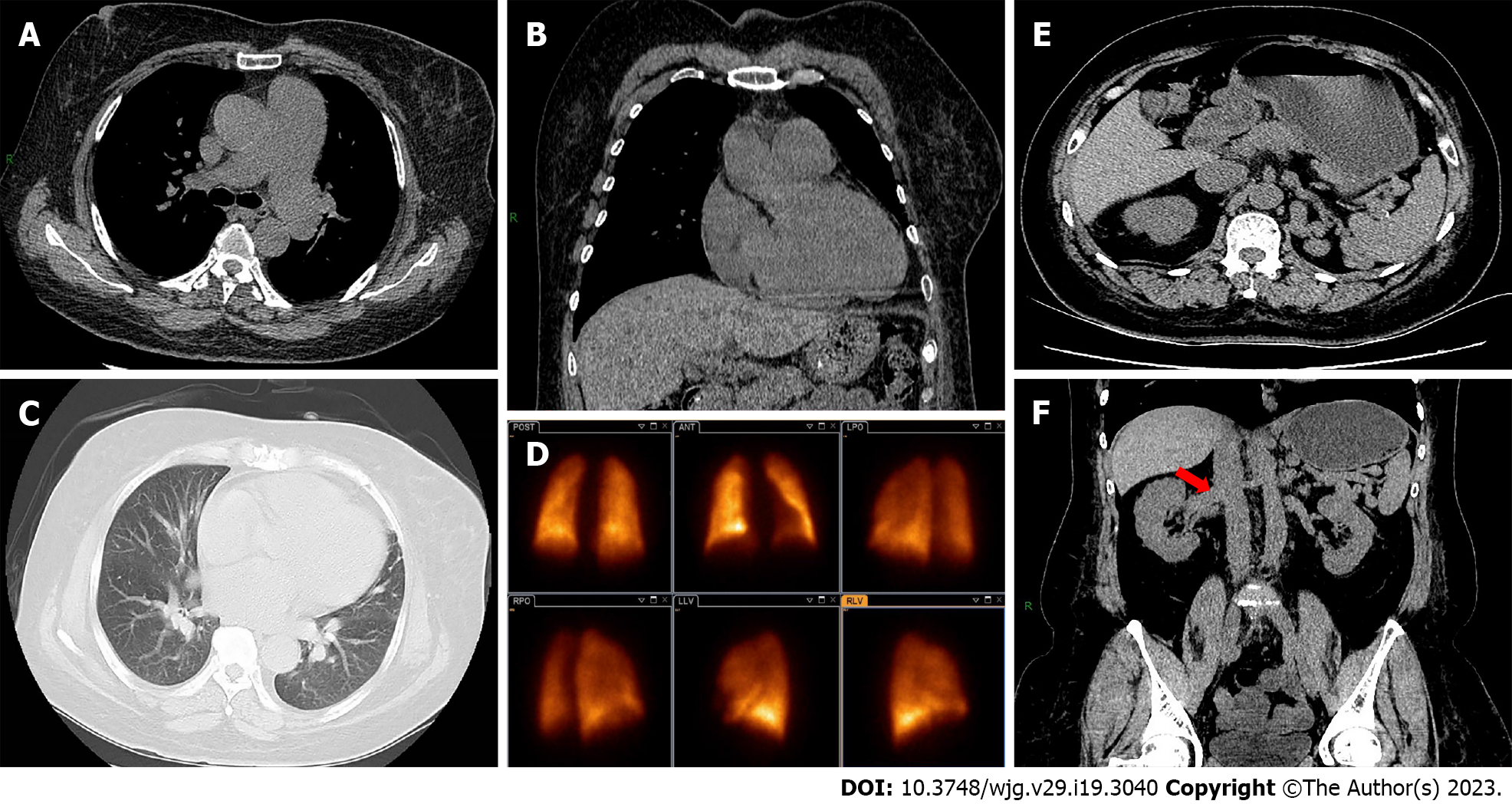

Muscle biopsy showed striated muscle atrophy with inflammatory cell infiltration (Figure 1A). Electrocardiography indicated a normal sinus rhythm (Figure 1B). Transthoracic echocardiography showed enlargement of the left atrium (43.7 × 45.2 × 60.0), right atrium (59.8 × 39.4), and right ventricle (49.3), normal left ventricular ejection fraction (71.3%), elevated pulmonary artery pressure (61 mmHg), and reduced diastolic function (Figure 1C-F). Chest computed tomography (CT) depicted pulmonary arterial hypertension, right atrium and right ventricle enlargement, and no parenchymal lung disease (Figure 2A-C). Pulmonary ventilation/perfusion scanning indicated no evidence of typical signs of thromboembolic disease (Figure 2D). Abdominal CT suggested normal liver size with a hepato-renal shunt and a spleno-renal shunt (Figure 2E and F). Right heart catheterization showed that mPAP was 55.33, pulmonary artery wedge pressure (PAWP) was 24, and pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) was 5.13 Woods units (WU) (Table 2).

| Parameter | Value | Unit |

| Heart rate | 76 | bpm |

| Pulmonary arterial pressure | 90/38/55.33 | mmHg |

| Right atrium pressure | 12.17 | mmHg |

| Pulmonary artery wedge pressure | 34/19/24 | mmHg |

| Pulmonary vascular resistance | 5.13 | Wood units |

| Pulmonary vascular resistance | 410.23 | dyne s/cm |

| Cardiac output | 9.53 | L/min |

| Cardiac index | 4.51 | L/min/m2 |

Based on the medical history, symptoms, and auxiliary examinations, a diagnosis of moderate PH, nephrotic syndrome, polymyositis, hypertension, and hepatitis C was determined.

The patient was treated with sildenafil 20 mg QD, macitentan 10 mg QD, irbesartan and hydrochlo

At the 3-mo follow up the patient’s dyspnea was dramatically improved and the 6-min walking distance was 300 m and pulmonary artery pressure drops to 50 mmHg.

HCV infection should be considered a systemic disease which is often associated with many extrahepatic manifestations. According to different studies, 40%-80% of patients infected with HCV develop at least one extrahepatic manifestation[4]. However, PH associated with HCV is relatively rare.

PH is divided into five clinical subgroups; pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), PH associated with left heart disease, PH associated with chronic lung disease and/or hypoxia, chronic thromboembolic, and PH with unclear and/or multifactorial mechanisms. Pre-capillary PH is hemodynamically defined as mPAP > 20 mmHg, PAWP ≤ 15 mmHg, and PVR > 2 WU. PAWP > 15 mmHg is the threshold of post-capillary PH. PVR is used to distinguish patients with post-capillary PH who have significant components of pre-capillary PH (PVR > 2 WU, combined with post-capillary and pre-capillary PH; CpcPH) from those who do not (PVR ≤ 2 WU, isolated post-capillary PH)[5]. The current patient had no relevant family history to support a heritable cause of PH. Valvular/congenital heart diseases, lung diseases, chronic pulmonary artery obstruction, and human immunodeficiency virus infection were systemically eliminated via relevant tests. Drugs were also unlikely to have caused her PH. The onset of PH predated the polymyositis, and connective tissue disease could also be excluded as a cause of PH. Thus, the possibility remained that PH associated with portal hypertension was due to chronic hepatitis C.

Portal PH (PoPH) is a well-known serious complication of portal hypertension in chronic liver disease. According to statistics, PoPH occurs in 1%–2% of patients with liver disease and portal hypertension[6]. The incidence of PoPH is higher in patients with HCV-related cirrhosis. In PAH registry studies, PoPH patients accounted for 5%–15% of PAH patients[7-9]. Hemodynamically, patients with PoPH had significantly higher cardiac output and lower systemic and PVR than patients with idiopathic PH[10]. The diagnosis of PoPH is based on the presence of otherwise unexplained pre-capillary PH in patients with portal hypertension or a portosystemic shunt[5]. In patients with an established diagnosis of PoPH, treatment should follow the same general principles as in other patients with PAH. PAH medications can affect gas exchange, which may deteriorate with vasodilators in patients with PoPH[11]. Various case series support the use of approved PAH medication in patients with PoPH. The survival and prognostic factors in PoPH remain controversial and are still poorly studied in the current era of PH management[7,12,13]. The current patient had a history of HCV infection, mild liver fibrosis, and hepato-renal shunt, thus the diagnosis of PoPH was considered. The results of right heart catheterization in the present patient were consistent with CpcPH, considering that there may have been other factors involved in PH, not only PoPH. The patient had a history of hypertension with left atrium and right atrium enlargement, and the N-terminal-pro B-type natriuretic peptide was elevated. Therefore, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction was involved in PH. Sildenafil, macitentan, diuretics, and angiotensin receptor blocker were prescribed. Short-term follow-up indicated improvement in respiratory status and increased activity tolerance. Confirmation of further efficacy requires long-term follow-up.

What is intriguing in the current case is the coexistence of PH, nephrotic syndrome, and polymyositis in a chronic hepatitis C patient, which is reported herein for the first time to our knowledge. Increasing epidemiological evidence indicates an association between HCV infection and renal disease, with membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis and membranous nephropathy being the most common[14]. The main clinical manifestations of nephrotic syndrome in HCV-infected patients are proteinuria and hypoalbuminemia, with or without a reduced glomerular filtration rate. Treatments include antiviral and nonspecific immunosuppressive therapy[15], but their efficacy and safety are controversial. HCV infection is often associated with autoimmune diseases such as cryoglobulinemia, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjogren’s syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, and polymyositis[1,16-18]. Most of these diseases appear to be related to virus-induced non-specific activation of the immune system, including autoantibody production, cryoglobulinemia, autoimmune thyroid disorders, and B cell lymphomas[19]. Although most data are based on small series and case reports, the association between chronic HCV infection and systemic autoimmune disease has received increasing attention. The exact etiology is unknown, but interaction between viral infection and autoimmune responses is thought to be one of the mechanisms involved. Chronic HCV infection should be considered as the cause of polymyositis if no other etiology is found. The diagnosis and treatment of HCV-associated autoimmune features has become a clinical challenge in patients with HCV infection. There are few reports on the outcome of corticosteroid treatment in patients with chronic HCV infection. Several studies have described rapid progression of liver disease after immunosuppression therapy in patients with chronic HCV infection[20]. The current patient’s nephrotic syndrome and polymyositis may have been caused by chronic HCV infection via an autoimmune mechanism. The patient was initially treated with methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide at the time of her polymyositis diagnosis. However, cyclophosphamide was discontinued and methylprednisolone was reduced because of her repeated episodes of abnormal behavior and coma due to hyperammonemia.

The optimal treatment strategy for hepatitis C-related extrahepatic manifestations remains to be determined. Due to the limited data available, more information is needed before definitive therapeutic recommendations can be established. The guidelines for treatment of HCV-related extrahepatic manifestations should be based on clinical features rather than underlying pathogenic mechanisms. Because of the poor prognosis and high mortality associated with these manifestations, the establishment of a safe and effective regimen for the therapy of HCV-related extrahepatic features requires further investigation.

Herein we have described a case of chronic hepatitis C with coexisting PoPH, nephrotic syndrome, and polymyositis. Increasing evidence supports a relationship between hepatitis C infection and diverse extrahepatic manifestations, but it is very rare to have multiple different extrahepatic manifestations in a single patient. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case. The exact mechanism by which hepatitis C mediated the development of diverse extrahepatic manifestations remains unclear. Further research on the specific mechanism involved is needed, to facilitated the development of safer and more effective treatment plans.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Beenet L, United States; Rodrigues AT, Brazil; Salvadori M, Italy S-Editor: Li L L-Editor: A P-Editor: Fan JR

| 1. | Ramos-Casals M, Trejo O, García-Carrasco M, Font J. Therapeutic management of extrahepatic manifestations in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2003;42:818-828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Simonneau G, Montani D, Celermajer DS, Denton CP, Gatzoulis MA, Krowka M, Williams PG, Souza R. Haemodynamic definitions and updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2019;53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1668] [Cited by in RCA: 2579] [Article Influence: 429.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hoeper MM, Humbert M, Souza R, Idrees M, Kawut SM, Sliwa-Hahnle K, Jing ZC, Gibbs JS. A global view of pulmonary hypertension. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4:306-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 588] [Article Influence: 65.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (35)] |

| 4. | Böckle BC, Sepp NT. Hepatitis C virus and autoimmunity. Auto Immun Highlights. 2010;1:23-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Humbert M, Kovacs G, Hoeper MM, Badagliacca R, Berger RMF, Brida M, Carlsen J, Coats AJS, Escribano-Subias P, Ferrari P, Ferreira DS, Ghofrani HA, Giannakoulas G, Kiely DG, Mayer E, Meszaros G, Nagavci B, Olsson KM, Pepke-Zaba J, Quint JK, Rådegran G, Simonneau G, Sitbon O, Tonia T, Toshner M, Vachiery JL, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Delcroix M, Rosenkranz S; ESC/ERS Scientific Document Group. 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2023;61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 803] [Cited by in RCA: 841] [Article Influence: 420.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mancuso L, Scordato F, Pieri M, Valerio E, Mancuso A. Management of portopulmonary hypertension: new perspectives. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:8252-8257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Krowka MJ, Miller DP, Barst RJ, Taichman D, Dweik RA, Badesch DB, McGoon MD. Portopulmonary hypertension: a report from the US-based REVEAL Registry. Chest. 2012;141:906-915. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lazaro Salvador M, Quezada Loaiza CA, Rodríguez Padial L, Barberá JA, López-Meseguer M, López-Reyes R, Sala-Llinas E, Alcolea S, Blanco I, Escribano-Subías P; REHAP Investigators. Portopulmonary hypertension: prognosis and management in the current treatment era - results from the REHAP registry. Intern Med J. 2021;51:355-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Savale L, Guimas M, Ebstein N, Fertin M, Jevnikar M, Renard S, Horeau-Langlard D, Tromeur C, Chabanne C, Prevot G, Chaouat A, Moceri P, Artaud-Macari É, Degano B, Tresorier R, Boissin C, Bouvaist H, Simon AC, Riou M, Favrolt N, Palat S, Bourlier D, Magro P, Cottin V, Bergot E, Lamblin N, Jaïs X, Coilly A, Durand F, Francoz C, Conti F, Hervé P, Simonneau G, Montani D, Duclos-Vallée JC, Samuel D, Humbert M, De Groote P, Sitbon O. Portopulmonary hypertension in the current era of pulmonary hypertension management. J Hepatol. 2020;73:130-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Galiè N, Torbicki A, Barst R, Dartevelle P, Haworth S, Higenbottam T, Olschewski H, Peacock A, Pietra G, Rubin LJ, Simonneau G; Grupo de Trabajo sobre el diagnóstico y tratamiento de la Hipertensión Arterial Pulmonar de la Sociedad Europea de Cardiología. [Guidelines on diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension]. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2005;58:523-566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Olsson KM, Meyer K, Berliner D, Hoeper MM. Development of hepatopulmonary syndrome during combination therapy for portopulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2019;53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Le Pavec J, Souza R, Herve P, Lebrec D, Savale L, Tcherakian C, Jaïs X, Yaïci A, Humbert M, Simonneau G, Sitbon O. Portopulmonary hypertension: survival and prognostic factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:637-643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sithamparanathan S, Nair A, Thirugnanasothy L, Coghlan JG, Condliffe R, Dimopoulos K, Elliot CA, Fisher AJ, Gaine S, Gibbs JSR, Gatzoulis MA, E Handler C, Howard LS, Johnson M, Kiely DG, Lordan JL, Peacock AJ, Pepke-Zaba J, Schreiber BE, Sheares KKK, Wort SJ, Corris PA; National Pulmonary Hypertension Service Research Collaboration of the United Kingdom and Ireland. Survival in portopulmonary hypertension: Outcomes of the United Kingdom National Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Registry. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2017;36:770-779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sabry AA, Sobh MA, Sheaashaa HA, Kudesia G, Wild G, Fox S, Wagner BE, Irving WL, Grabowska A, El-Nahas AM. Effect of combination therapy (ribavirin and interferon) in HCV-related glomerulopathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:1924-1930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Fabrizi F, Martin P, Cacoub P, Messa P, Donato FM. Treatment of hepatitis C-related kidney disease. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2015;16:1815-1827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Arrais de Castro R, Vilas P, Borges-Costa J, Tato Marinho R. Hepatitis C virus infection: 'beyond the liver'. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Uruha A, Noguchi S, Hayashi YK, Tsuburaya RS, Yonekawa T, Nonaka I, Nishino I. Hepatitis C virus infection in inclusion body myositis: A case-control study. Neurology. 2016;86:211-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Aisa Y, Yokomori H, Kashiwagi K, Nagata S, Yanagisawa R, Takahashi M, Hasegawa H, Tochikubo Y. Polymyositis, pulmonary fibrosis and malignant lymphoma associated with hepatitis C virus infection. Intern Med. 2001;40:1109-1112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bianchi FB, Muratori P, Granito A, Pappas G, Ferri S, Muratori L. Hepatitis C and autoreactivity. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39 Suppl 1:S22-S24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Rockstroh JK, Spengler U, Sudhop T, Ewig S, Theisen A, Hammerstein U, Bierhoff E, Fischer HP, Oldenburg J, Brackmann HH, Sauerbruch T. Immunosuppression may lead to progression of hepatitis C virus-associated liver disease in hemophiliacs coinfected with HIV. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:2563-2568. [PubMed] |