Published online Dec 14, 2022. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v28.i46.6573

Peer-review started: June 27, 2022

First decision: August 19, 2022

Revised: September 9, 2022

Accepted: November 16, 2022

Article in press: November 16, 2022

Published online: December 14, 2022

Processing time: 163 Days and 22.1 Hours

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a highly prevalent gastrointestinal disorder with poor response to treatment. IBS with predominant diarrhea (IBS-D) is accompanied by abdominal pain as well as high stool frequency and urgency. Purified clinoptilolite-tuff (PCT), which is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use as a dietary supplement with the brand name G-PUR®, has previously shown therapeutic potential in other indications based on its physical adsorption capacity.

To assess whether symptoms of IBS-D can be ameliorated by oral treatment with PCT.

In this randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind pilot study, 30 patients with IBS-D diagnosis based on Rome IV criteria were enrolled. Following a 4-wk run-in phase, 14 patients were randomized to receive a 12-wk treatment with G-PUR® (2 g three times daily), and 16 patients received placebo. The relief from IBS-D symptoms as measured by the proportion of responders according to the Subject’s Global Assessment (SGA) of Relief was assessed as the primary outcome. For the secondary outcomes, validated IBS-D associated symptom questionnaires, exploratory biomarkers and microbiome data were collected.

The proportions of SGA of Relief responders after 12 wk were comparable in both groups, namely 21% in the G-PUR® group and 25% in the placebo group. After 4 wk of treatment, 36% of patients in the G-PUR® group vs 0% in the placebo group reported complete or considerable relief. An improvement in daily abdominal pain was noted in 94% vs 83% (P = 0.0353), and the median number of days with diarrhea per week decreased by 2.4 d vs 0.3 d in the G-PUR® and placebo groups, respectively. Positive trends were observed for 50% of responders in the Bristol Stool Form Scale. Positive trends were also noted for combined abdominal pain and stool consistency response and the Perceived Stress Questionnaire score. Only 64% in the G-PUR® group compared to 86% in the placebo group required rescue medication intake during the study. Stool microbiome studies showed a minor increase in diversity in the G-PUR® group but not in the placebo group. No PCT-related serious adverse events were reported.

In this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, the PCT product, G-PUR®, demonstrated safety and clinical benefit towards some symptoms of IBS-D, representing a promising novel treatment option for these patients.

Core Tip: The purified clinoptilolite-tuff (PCT) product, G-PUR®, provided improvement in abdominal symptoms and stool abnormalities in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) with predominant diarrhea. Additionally, it reduced the use of rescue medication and tended to enrich gut microbiome diversity compared to placebo, while showing no safety concerns. Hence, the PCT product, G-PUR®, represents a promising novel treatment option for patients with IBS with predominant diarrhea.

- Citation: Anderle K, Wolzt M, Moser G, Keip B, Peter J, Meisslitzer C, Gouya G, Freissmuth M, Tschegg C. Safety and efficacy of purified clinoptilolite-tuff treatment in patients with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea: Randomized controlled trial. World J Gastroenterol 2022; 28(46): 6573-6588

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v28/i46/6573.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v28.i46.6573

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a chronic gastrointestinal disorder of high global prevalence with a substantial impact on quality of life and is associated with abdominal pain and altered bowel habits. According to the Rome IV criteria, IBS is characterized by recurrent abdominalgia occurring at least once a week over a period of 3 mo, together with at least two of the following criteria: Pain related to defecation; change in stool frequency; or change in form/appearance of stool, with the onset of symptoms at least 6 mo prior to diagnosis. IBS can be divided into IBS subgroups with predominant constipation, diarrhea (IBS-D), mixed bowel habits, or unclassified[1,2]. The prevalence of IBS reported in the literature ranges between 1%-45%, reflecting the geographical and methodological variety. IBS affects at least twice as many women as men, occurring in women primarily in the late teenage years to the mid-40s[3].

While no underlying morphologic correlation has yet been identified in IBS, the multifactorial biopsychosocial model postulates a contribution of genetic predisposition, history of gastrointestinal infections with possible increase in gut permeability and activation of the immune system, malab

Several natural mineral adsorbents, e.g., dioctahedral smectite, spherical carbon, bentonite or zeolites, have been investigated in patients with IBS and have shown variable degrees of effectiveness in alleviating symptoms[7-11]. Clinoptilolite, a commonly found mineral from the group of natural zeolites, is characterized by high ad/absorptive capacity, the ability to support ion exchange and to act as a molecular sieve, owing to its microporous crystalline structure with multiple microcavities[12,13]. A number of clinical studies have evaluated the potential of clinoptilolite-based products in relieving symptoms of gastric discomfort, such as diarrhea[14], gastric hyperacidity[15,16], or veisalgia[17]. Furthermore, clinoptilolite has shown benefits in enhancing the intestinal wall integrity as indicated by decreased concentrations of the tight-junction modulator zonulin, reduction of inflammation-associated markers, such as α1-antitrypsin and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and a trend towards beneficial microbiome changes[10,18].

In a pilot study with clinoptilolite in IBS patients, significant decreases in clinical parameters such as pain, distension or bowel habits were reported. Despite the pronounced placebo effect seen in this study, clinoptilolite showed a trend towards an augmented clinical benefit[19]. Based on these encouraging results, we aimed to determine the clinical effectiveness and safety of purified clinoptilolite-tuff (PCT) product G-PUR® in patients with IBS-D symptoms in a randomized controlled trial.

We conducted a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, parallel-arm study to evaluate the safety and clinical efficacy of a 12-wk oral treatment with G-PUR® (2 g three times daily) or matching placebo in a cohort of 30 patients with IBS-D diagnosis based on Rome IV criteria[2]. Glock Health, Science and Research GmbH acted as sponsor of this multicenter study and was responsible for the design and report of this study. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Vienna (No. 1295/2019), Ethics Committee of Upper Austria (No. 1208/2019) and the Austrian Federal Office for Safety in Health Care (BASG) and is registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04138186). This study was conducted at the Department of Clinical Pharmacology at the Medical University of Vienna and Klinikum Wels-Grieskirchen, Department of Internal Medicine in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the ISO 14155 guideline. All study participants provided written informed consent before any study-specific procedures were performed. The clinical investigation was initiated in September 2019 and completed in February 2021.

Eligible patients had to be between 18-75 years of age and fulfill the Rome IV criteria for IBS-D, i.e. more than 25% of the bowel movements graded as the Bristol Stool Form Scale (BSFS) type 6 or 7 (equivalent to mild/severe diarrhea) and less than 25% of bowel movements graded as type 1 or 2 (equivalent to mild/severe constipation)[20]. Moreover, patients had to have moderate to severe abdominal pain as defined by an IBS Symptoms Severity Scale (IBS-SSS) score > 175 and stable eating habits 1 mo prior to randomization. Patients > 50 years of age had to have an unremarkable colonoscopy within the preceding 5 years. Patients were excluded if they failed to record > 50% of daily diary entries during the screening/run-in phase, had rectal bleeding in the absence of documented bleeding hemorrhoids or anal fissures, had a history of major gastrointestinal surgery, had been or were being treated with antibiotic medicines, including rifaximin, or used pro- or antikinetic agents (except as a rescue medication, see below), tricyclic antidepressants or immunosuppressive therapy. Patients with a history of positive tests for ova, parasites, or Clostridioides difficile infection had to undergo repeated testing with negative results during the screening/run-in phase.

G-PUR® is a PCT, prepared from a high-grade raw material with low heavy metal content, sourced from a mine in the eastern Slovak Republic[21,22] and has been marketed in the United States as a dietary supplement since 2016. G-PUR® has been successfully applied in different therapeutic indications[23,24]. The patented purification process is technically based on ion exchange mechanisms of the clinoptilolite mineral, micronization and terminal heating, which results in the removal of all natural impurities and a homogeneous, very fine-grained particle size[25]. The production process is thoroughly quality-assured, meeting all required regulatory standards. The purified product has been evaluated by independent laboratories and conforms with the safety requirements for human consumption. Besides the very high clinoptilolite content in the purified product (> 75%), other mineral phases like cristobalite, feldspars, accessory biotite and quartz are contents of G-PUR®. The almost completely inert product is characterized by a high adsorption capacity for a variety of toxins, heavy metals and other undesirable substances[26-28]. G-PUR® is not absorbed or metabolized in the gastrointestinal tract and therefore excreted unchanged via stool. The therapeutic potential is based on the physical adsorption capacity of G-PUR®[23,24].

For this clinical investigation, G-PUR® was provided in hard-gelatin Capsugel® AAA capsules, each containing 400 mg of PCT. Colloidal silicon dioxide (Aerosil®) was added as an excipient at a concentration of 0.5% to enhance flowability and enable accurate filling of the capsules. Placebo was provided in identical-looking capsules, each containing 400 mg maltodextrin and 0.5% magnesium stearate as excipient.

Randomization was performed by Assign Data Management and Biostatistics GmbH (Innsbruck, Austria). Based on the randomization list, blinding was performed centrally by NUVISAN Pharma Services. The randomization list was prepared by computer software (random permuted blocks with confidential block size) using a 1:1 ratio. One sealed randomization list was stored at Assign Data Management and Biostatistics and was not to be opened until after database lock. Patients fulfilling all eligibility criteria as confirmed at visit 3 were enrolled into the clinical investigation and randomized. Enrolled patients were allocated to the next highest randomization number (medication kit identification number). Investigational site staff, including the investigator, and patients were blinded to treatment allocation.

Eligible patients underwent a 4-wk screening/run-in phase, followed by a 12-wk double-blind treatment phase and a 2-wk withdrawal phase. The total study duration per patient was 18–21 wk and included seven study visits. Patients also had to complete at least 14 d of baseline diary entries over the 28-d screening/run-in phase. Throughout the double-blind 12-wk treatment phase and the 2-wk withdrawal phase, a limited use of loperamide and hyoscine butylbromide was allowed as rescue medication. Following the run-in phase, patients were randomized to receive five G-PUR® capsules or identical-looking placebo capsules, three times a day before meals with a minimum of 200 mL tap water. The total daily dose of PCT in the treatment arm was 6 g. Due to the high adsorption capacity and the possible risk of interaction between the PCT product G-PUR® and other medicines, participants were instructed to allow for a minimum 2-h window between G-PUR® and other oral medication intake. Throughout the entire study duration, patients were supported by health care professionals and psychological therapists.

According to the guidelines by the European Medicines Agency (EMA)[29] and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)[30], abdominal pain based on an 11-point numerical rating scale as well as stool consistency according to the BSFS should be assessed daily to determine the effect of medicine treatment in patients with IBS-D. Accordingly, patients kept daily diaries of abdominal pain, bloating, urgency, stress, stool frequency, stool consistency, treatment adherence and use of any concomitant or rescue medications by using an electronic patient-reported outcome (ePRO) system throughout the study. At the end of the treatment phase, i.e. at visit 6, ePRO diary usability was evaluated.

The primary objective of this clinical investigation was to assess the relief from IBS-D symptoms after a 12-wk treatment with G-PUR® (2 g three times daily) vs placebo as measured by the Subject’s Global Assessment (SGA) of Relief questionnaire[31]. The secondary objectives were to assess the safety and tolerability of treatment with G-PUR®, impact of treatment on additional IBS-related symptoms, bowel habits, health-related quality of life, psychological status (i.e. anxiety, depression, and stress), patient satisfaction with the ePRO diary and additional exploratory parameters including microbiome analysis.

The primary endpoint of this clinical investigation was the proportion of responders according to the SGA of Relief[31] using the last four post-randomization assessments in the treatment period, or if fewer than four post-randomization SGAs were available, then on all post-randomization SGA of Relief questionnaires. Patients were considered responders if they answered “considerably relieved” or “completely relieved” at least 50% of the time or at least “somewhat relieved” 100% of the time.

The following variables were assessed as secondary endpoints: (1) SGA of Relief estimated by time point, absolute change in SGA of Relief compared to baseline and relationship between SGA of Relief by treatment groups in a logistic regression model with IBS-SSS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), pain intensity, stool frequency and stool consistency at visit 3 as independent variables; (2) Incidence of (serious) adverse events (AEs); (3) Daily intensity of abdominal pain using an 11-point numerical rating scale (NRS), including the proportion of abdominal pain responders, with abdominal pain response defined as an at least 30% improvement in abdominal pain on at least 50% of days with available ePRO diary entries compared to the patient’s worst abdominal pain reported in the screening/run-in phase (baseline abdominal pain), additional analyses of abdominal pain response, defined as an at least (a) 40%, 50% or 60% improvement in abdominal pain on at least 50% of days; (b) 30%, 40%, 50% or 60% improvement in abdominal pain on at least 40% of days; or (c) 30%, 40%, 50% or 60% improvement in abdominal pain on at least 30% of days, with available ePRO entries compared to the patient’s worst baseline abdominal pain or proportion of days with an at least 30% improvement in abdominal pain compared to the patient’s worst baseline abdominal pain; (4) Daily intensity of bloating using an 11-point NRS; (5) Daily intensity of urgency using an 11-point NRS; (6) Daily stress level using an 11-point NRS; (7) Daily stool frequency; (8) Daily stool consistency using the BSFS[32], including the proportion of BSFS responders, with BSFS response defined as an at least 50% reduction in the number of days per week with at least one BSFS type 6 or 7 stool (‘diarrhea’) compared to the screening/run-in phase (‘baseline diarrhea’), daily proportion of patients with BSFS type 6 or 7 (i.e. diarrhea) and number of days per week with diarrhea; (9) Proportion of patients with a combined abdominal pain and BSFS response; (10) Patient compliance with daily ePRO diary reporting; (11) ePRO diary usability; (12) Gastrointestinal symptoms using the IBS-SSS[33] during each study visit assessing the proportion of patients with a ≥ 50% reduction in the IBS-SSS score and number of pain-free days using the IBS-SSS; (13) Quality of life using the 12-item Short Form Survey (commonly referred to as SF-12)[34]; (14) Anxiety and depression using the HADS[35]; (15) Stress response using the Perceived Stress Ques

The following variables were assessed as exploratory endpoints before and after 12 wk of treatment: (1) Indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO)[40] and zonulin[41] in capillary blood; (2) Bile acid[42], human beta defensin 2 (HBD2)[43], gluten[44] and zonulin[45] in stool; and (3) Microbiome in stool (next-generation sequencing; myBioma GmbH, Vienna, Austria).

Safety analysis included AEs and adverse device effects (ADEs), device deficiency, laboratory results and aluminum levels.

No formal sample size calculation was performed owing to the exploratory pilot study design. Overall, 30 patients were randomized to treatment with either G-PUR® or placebo. Analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis Software 9.3 or higher (SAS Inc., Cary, NC, United States). The Full Analysis Set analysis was provided in this publication including data from all patients who were randomized. Patients were analyzed in the treatment group they were randomized to, regardless of the actual treatment received. For the inferential analysis of the primary endpoint, the rate of responders according to SGA was compared in an intention-to-treat analysis between the two treatment groups using Fisher’s exact test. A two-sided significance level of 5% was applied. For all secondary efficacy endpoints, categorical variables were compared between treatment groups using Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables were compared using a Wilcoxon rank-sum test (Mann-Whitney U test). In general, the last available post-randomization assessment during the treatment period was used to compare secondary efficacy parameters between treatment groups. Data were summarized by treatment group and, where appropriate, by visit. Descriptive statistics (number of observations, mean, standard deviation, minimum, median and maximum) were provided for continuous variables. Frequency counts and percentages were presented for categorical variables. Five patients who were withdrawn from the study prematurely were not included in this assessment of adherence and efficacy. Logistic regression analysis for parameters SGA of Relief and IBS-SSS, HADS, NRS and stool frequency and consistency included only patients with available results for all relevant independent variables (n = 27).

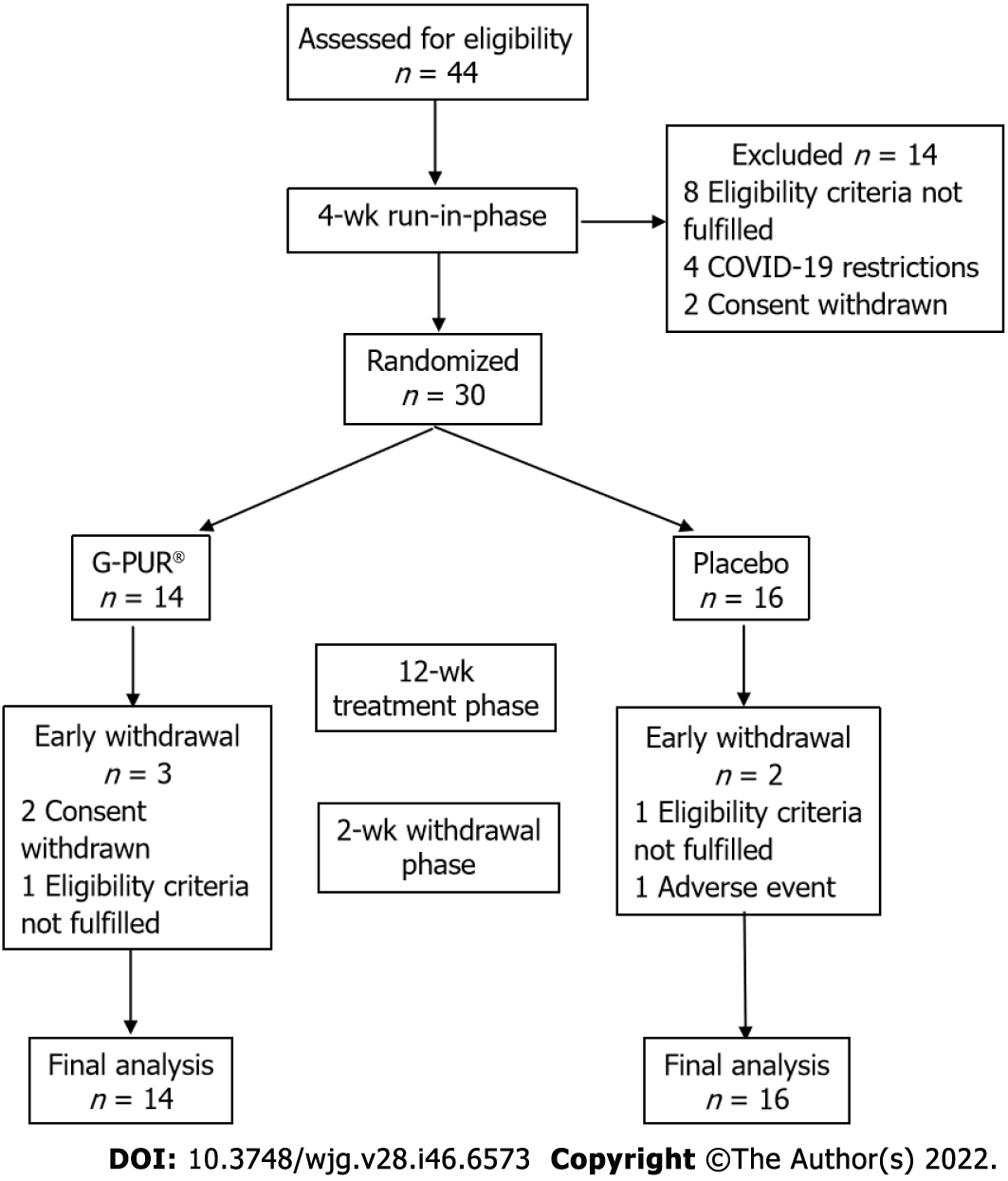

We screened 44 patients in order to include 30 trial participants, of whom 14 were randomized into the G-PUR® arm and 16 into the placebo arm (Figure 1). The two study groups were similar regarding their demographic and baseline characteristics, but patients in the G-PUR® group had a slightly longer disease duration. The median age of the study population was 34 years (range: 20–73), and 21 of the 30 patients (70%) were women. Baseline patient demographics and concomitant medications are summarized in Table 1 and medical history in Table 2. At baseline, analgesic and antipyretic medications were used by 2 patients (14%) in the G-PUR® arm and 8 patients (50%) in the placebo arm; the use of medicines for functional gastrointestinal disorder was comparable in both groups.

| Characteristics and medications | G-PUR®, n = 14 | Placebo, n = 16 | Total, n = 30 | |

| Age, yr | 34 (range: 24–61) | 35 (range: 20–73) | 34 (range: 20–73) | |

| Sex | Male | 5 (35%) | 4 (25%) | 9 (30%) |

| Female | 9 (64%) | 12 (75%) | 21 (70%) | |

| Duration of IBS symptoms, yr | 12 (IQR: 6–19) | 9 (IQR: 6–21) | 11 (IQR: 6–20) | |

| Duration of IBS diagnosis, yr | 8 (IQR: 3–11) | 2 (IQR: 1–11) | 4 (IQR: 1–11) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 21 (IQR: 20–25) | 24 (IQR: 21–26) | 23 (IQR: 20–26) | |

| Smoking status | Non-smoker | 9 (64%) | 11 (69%) | 20 (67%) |

| Ex-smoker | 3 (21%) | 4 (25%) | 7 (23%) | |

| Smoker | 2 (14%) | 1 (6%) | 3 (10%) | |

| Concomitant medications | ||||

| Any concomitant medication | 12 (86%) | 15 (94%) | 27 (90%) | |

| Analgesics | 2 (14%) | 8 (50%) | 10 (33%) | |

| Drugs for functional gastrointestinal disorders | 4 (29%) | 5 (31%) | 9 (30%) | |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | 4 (29%) | 4 (25%) | 8 (27%) | |

| Systemic antihistamines | 5 (36%) | 1 (6%) | 6 (20%) | |

| Loperamide PRN | 2 (14%) | 2 (13%) | 4 (13%) | |

| Antacids | 1 (7%) | 1 (6%) | 2 (7%) | |

| Hypnotics, sedatives, antipsychotics | 0 (0%) | 2 (13%) | 2 (7%) | |

| Tonics | 1 (7%) | 1 (6%) | 2 (7%) | |

| Systemic antibiotics1 | 0 (0%) | 1 (6%) | 1 (3%) | |

| Digestives, incl. enzymes | 1 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | |

| Drugs for constipation | 1 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | |

| System organ class | G-PUR®, n = 14 | Placebo, n = 16 | Total, n = 30 |

| MedDRA term | |||

| Immune system disorders | 10 (71%) | 6 (38%) | 16 (53%) |

| Seasonal allergy | 7 (50%) | 3 (19%) | 10 (33%) |

| Drug hypersensitivity | 2 (14%) | 2 (13%) | 4 (13%) |

| Allergy to animal | 1 (7%) | 1 (6%) | 2 (7%) |

| Allergy to plants | 2 (14%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (7%) |

| Food allergy | 1 (7%) | 1 (6%) | 2 (7%) |

| Mite allergy | 1 (7%) | 1 (6%) | 2 (7%) |

| Perfume sensitivity | 1 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 3 (21%) | 7 (44%) | 10 (33%) |

| Vitamin D deficiency | 1 (7%) | 5 (31%) | 6 (20%) |

| Lactose intolerance | 2 (14%) | 1 (6%) | 3 (10%) |

| Fructose intolerance | 1 (7%) | 1 (6%) | 2 (7%) |

| Folate deficiency | 0 (0%) | 1 (6%) | 1 (3%) |

| Food intolerance | 0 (0%) | 1 (6%) | 1 (3%) |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 0 (0%) | 1 (6%) | 1 (3%) |

| Psychiatric disorders | 3 (21%) | 5 (31%) | 8 (27%) |

| Depression | 2 (14%) | 2 (13%) | 4 (13%) |

| Anxiety disorder | 0 (0%) | 3 (19%) | 3 (10%) |

| Burnout syndrome | 1 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) |

| Sleep disorder | 1 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 1 (7%) | 5 (31%) | 6 (20%) |

| Gastritis | 0 (0%) | 3 (19%) | 3 (10%) |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 1 (7%) | 1 (6%) | 2 (7%) |

| Hiatus hernia | 0 (0%) | 1 (6%) | 1 (3%) |

| Nausea | 0 (0%) | 1 (6%) | 1 (3%) |

After 12 wk of treatment the proportion of responders according to the SGA of Relief was 21% (n = 3) in the G-PUR® group and 25% (n = 4) in the placebo group (P = 1.0; Table 3).

| Outcome variable | G-PUR®, n = 14 | Placebo, n = 16 | RD/MD (95%CI) | Odds ratio (95%CI) | P value | |

| SGA of Relief responders, end of study1 | 3 (21%) | 4 (25%) | 0.04 (-0.28-0.38) | 0.82 (0.18-3.73) | 1.0000 | |

| Abdominal pain responders2 | 13 (93%) | 13 (81%) | 0.12 (-0.20-0.40) | 3 (0.39-41.55) | 0.6015 | |

| Daily abdominal pain reduction3 | 94 (IQR: 81-100) | 83 (IQR: 65-92) | -14.9 (-31.87-2.07) | N/A | 0.0353 | |

| Proportion of BSFS 50% responders | 7 (50%) | 5 (31%) | 0.19 (-0.19-0.51) | 2.2 (0.55-11.05) | 0.4572 | |

| Proportion of BSFS 30% responders | 10 (71%) | 7 (44%) | 0.28 (-0.11-0.58) | 3.21 (0.76-12.03) | 0.1590 | |

| Combined abdominal pain and BSFS 50% response | 6 (43%) | 4 (25%) | 0.18 (-0.19-0.50) | 2.25 (0.49-8.68) | 0.4421 | |

| Decrease in d with diarrhea per week | 2.4 | 0.3 | N/A | N/A | 0.4176 | |

| IBS-SSS | -90 (IQR: -170 to -40) | -55 (IQR: -100 to -10) | 31.6 (-42.25-105.5) | N/A | 0.3950 | |

| SF-12 | 53 (IQR: 50-55) | 49 (IQR: 42-51) | -5.40 (-9.15 to -1.65) | N/A | 0.0127 | |

| PSQ absolute change | Total | -7 (IQR: -28-0) | 5 (IQR: -5-12) | 11.0 (-2.65-24.65) | N/A | 0.0843 |

| Tension | -20 (IQR: -40-0) | -3 (IQR: -13-13) | 16.2 (0.7-31.7) | N/A | 0.0399 | |

| Joy | 13 (IQR: -7-20) | -10 (IQR: -20-0) | -10.4 (-25.3-4.5) | N/A | 0.1176 | |

| Demands | -7 (IQR: -33-13) | 10 (IQR: -7-20) | 14.3 (-5.35-33.95) | N/A | 0.1795 | |

| Worries | 0 (IQR: -13-0) | 0 (IQR: -7-13) | 3.2 (-11.56-17.96) | N/A | 0.5587 | |

A between-group difference in SGA of Relief was obvious after 4 wk of treatment, with 36% of patients in the G-PUR® group reporting complete or considerable relief, compared to 0% in the placebo group (Figure 2). Consistent with this observation, the median proportion of days with an at least 30% improvement in abdominal pain compared to the patient’s worst abdominal pain at baseline was higher in the G-PUR® group (94%) than in the placebo group (83%, P = 0.0353). This was also seen for abdominal pain response, where 93% of patients (n = 13) in the G-PUR® group were classified as responders compared with 81% (n = 13) in the placebo group (P = 0.6015). Although not reaching the threshold for statistical significance, the proportion of BSFS responders was more pronounced in the G-PUR® group. However, the median number of days with diarrhea per week decreased by 2.4 d in the G-PUR® group and by only 0.3 d in the placebo group.

Quality of life as assessed using the SF-12, anxiety and depression evaluated using the HADS, and IBS-SSS scores showed no absolute differences between groups. The significant difference between groups at the end of the study was likely related to the less favorable baseline PCS-12 in the placebo group. Overall, 7/11 patients (64%) in the G-PUR® group and 12/14 patients (86%) in the placebo group reported intake of rescue medication during the trial. In the analysis of perceived stress level, the change in total PSQ score was not different between groups. When score items were analyzed separately, ‘tension’ was significantly relieved in patients receiving G-PUR® (P = 0.0399 vs placebo). The main secondary outcomes are summarized in Table 3.

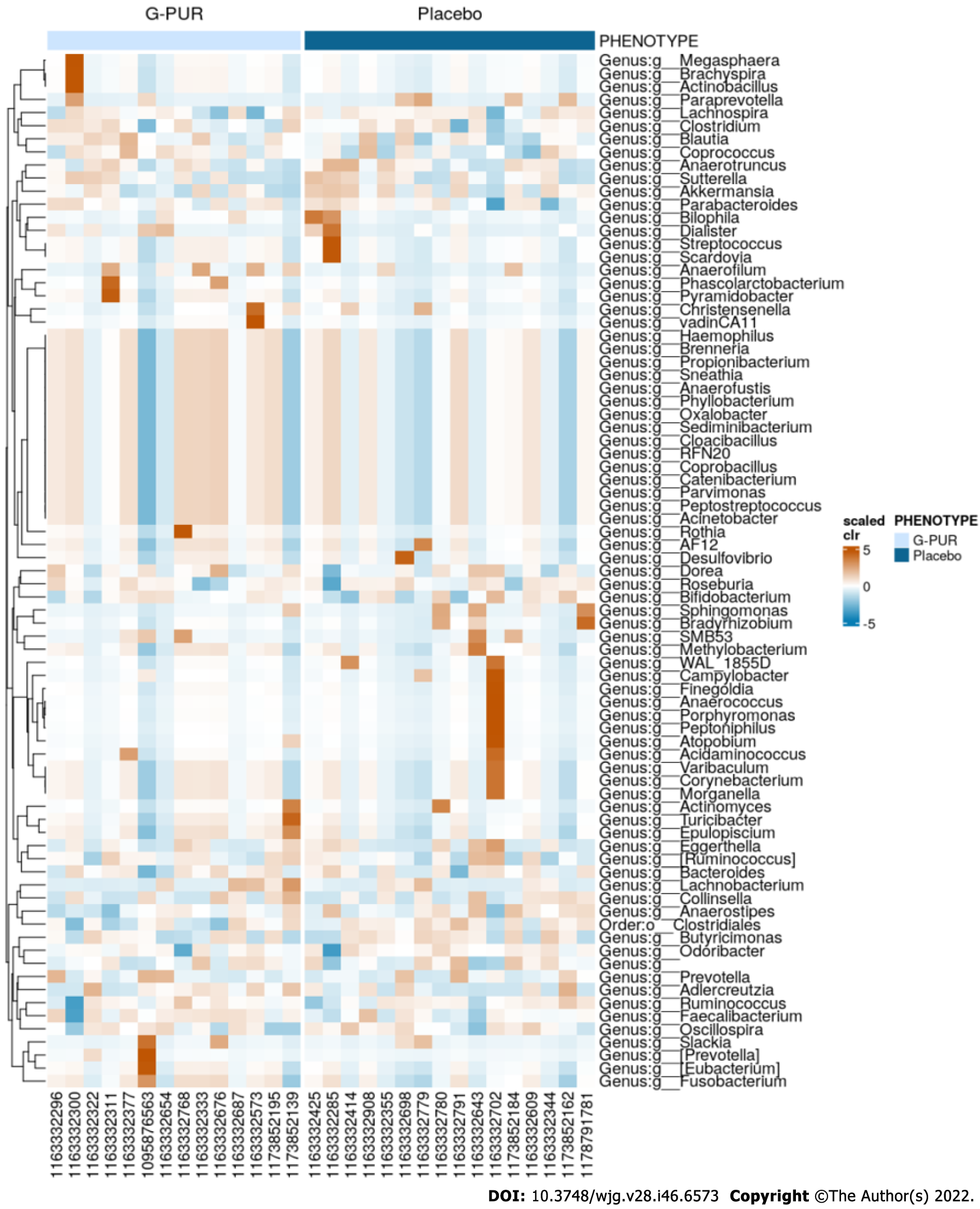

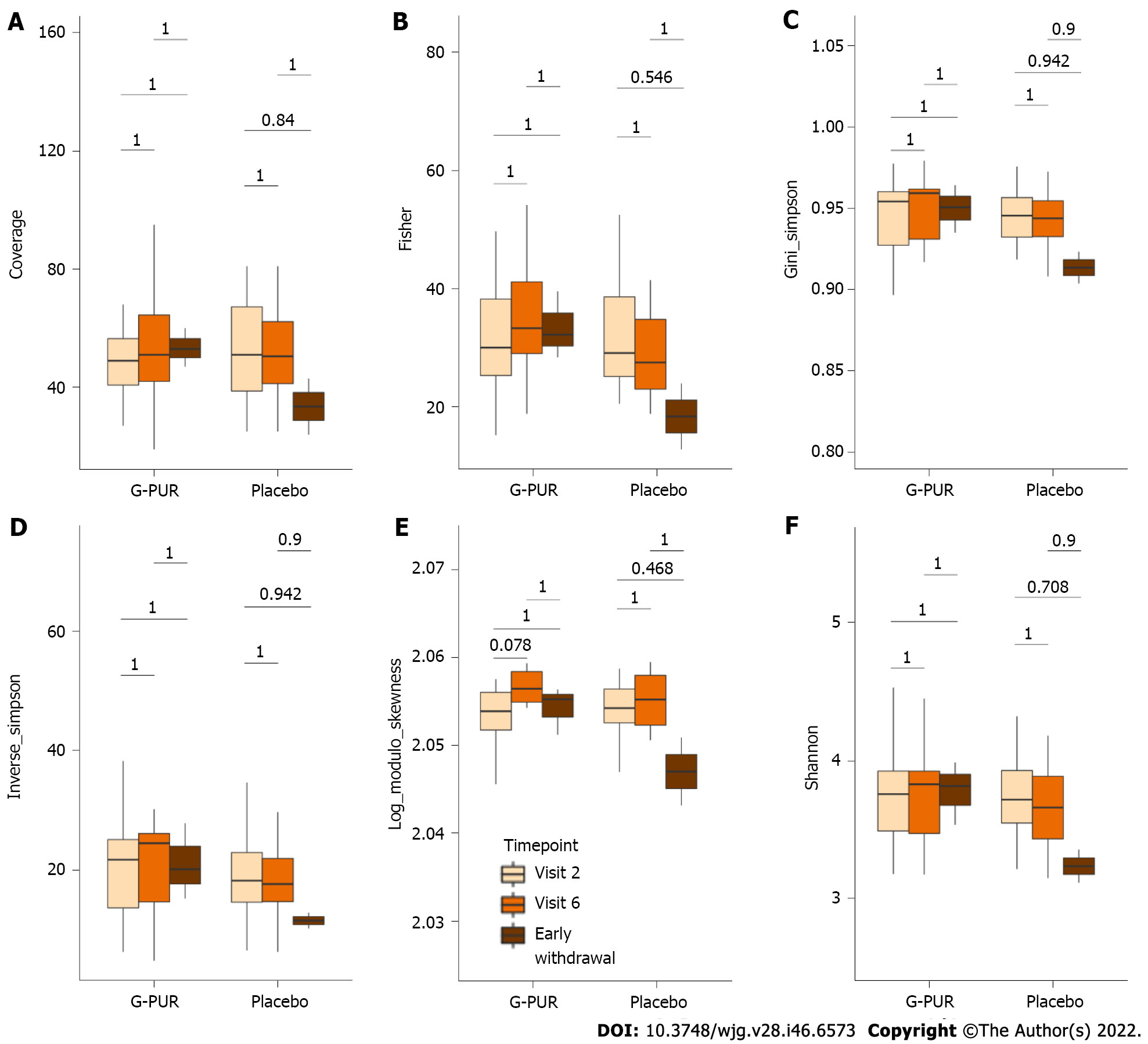

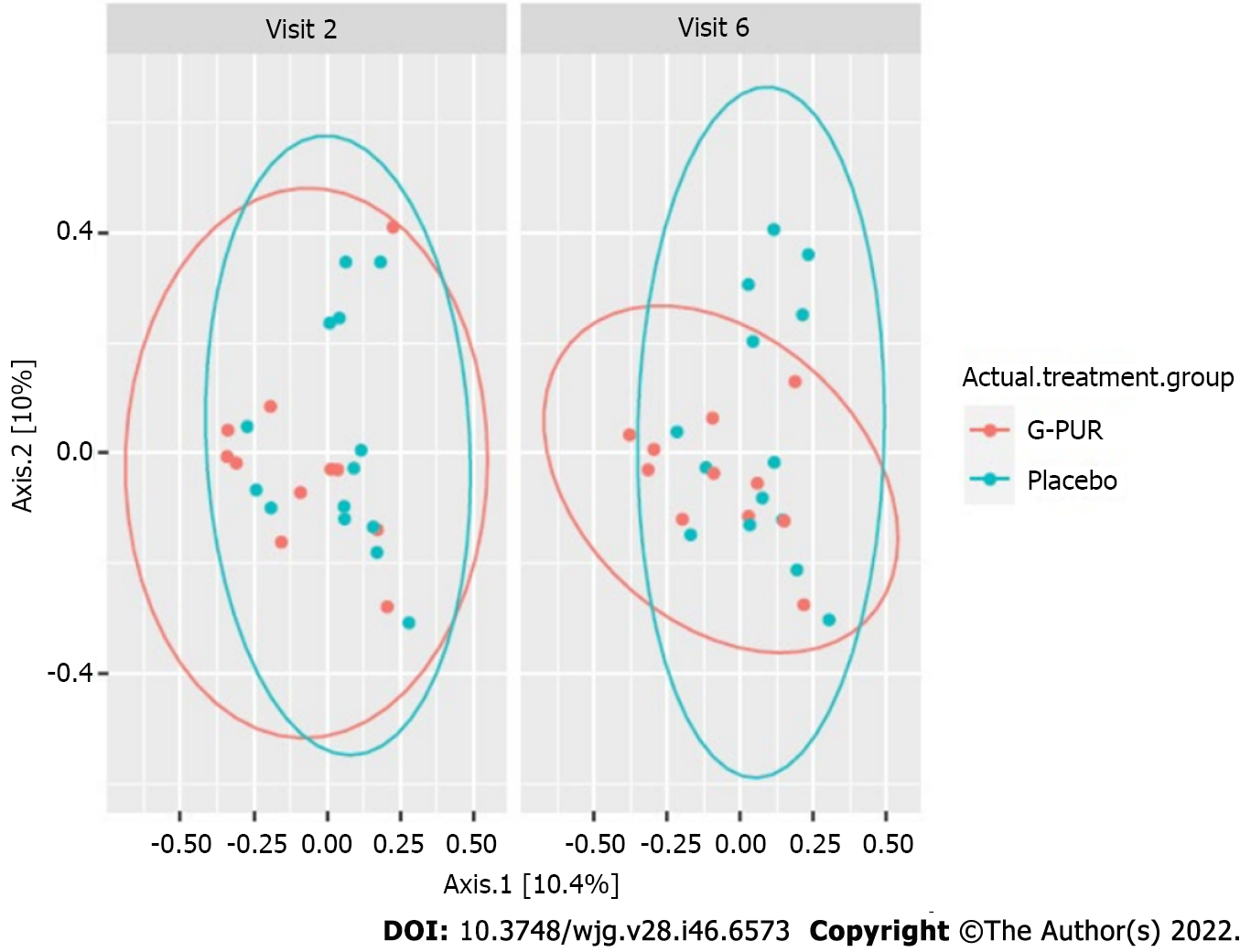

In the exploratory biomarker analysis, IDO and zonulin levels in capillary blood and levels of bile acid, HBD2 and zonulin in stool were not altered during the observation period. Microbiome studies in stool showed a mild increase in diversity in the G-PUR® group but not in the placebo group. Although these effects were minor, this finding was further supported by the spatial changes of beta diversity seen in the G-PUR® group but not in the placebo group (Figures 3-5).

G-PUR® was well tolerated throughout the study. Only 2 of the 69 AEs in the G-PUR® group, i.e. mild mucosal dryness and mild abdominal distension, were considered treatment-related ADEs. With an overall exposure of 805 treatment days in the G-PUR® group, this corresponds to an ADE rate per patient year of 0.9, which was similar to placebo (0.7 per patient year). The AE rate per patient year differed between groups, with 31 events per patient year in the G-PUR® group and 90 in the placebo group. With many of the reported AEs related to the patients’ IBS symptoms, this large between-group difference in AE frequency may be at least in part related to the effects of treatment. Because G-PUR® contains alumino-silicates, the release of aluminum has been a potential source of concern. In this study, an elevation in aluminum levels above normal limits was not seen in any of the patients of the entire cohort. In the G-PUR® group, the proportion of patients with aluminum levels below the reference range increased from 14% (n = 2) at baseline to 40% (n = 4) at the end of treatment. In the placebo group, this proportion was 13% (n = 2) at baseline and 0% (n = 0) at the end of treatment.

This study provided evidence for the effectiveness and safety of the PCT product G-PUR® in the treatment of IBS-D. While no consistent change in SGA of Relief in response to G-PUR® was demonstrable, the favorable results of G-PUR® were seen in the reduction of cardinal symptoms of IBS-D, i.e. abdominal pain and improvement in stool consistency, compared to placebo. This is further supported by symptom improvements over time and lower use of rescue medications in the G-PUR® group than in the placebo group. Importantly, the proportion of days with an at least 30% improvement in abdominal pain was significantly higher in the G-PUR® group compared to placebo. The particular attention and patient support in this study by health care professionals and psychological therapists might have contributed to the strong placebo effect and reduced disease-associated anxiety in both groups. While the PSQ total score improved in the G-PUR® group, it deteriorated in the placebo group, with the between-group difference in change over time trending towards significance (P = 0.0843). This advantage of G-PUR® was driven mainly by the ‘tension’ subscore, whose absolute change differed significantly between groups (P = 0.0399) and to a lesser extent by the ‘joy’ and ‘demands’ subscores.

The comparison of IBS treatment efficacy is generally difficult because there have been only a few head-to-head RCTs. The fluctuations of IBS symptoms over time and the scale of the placebo effect complicates endpoint assessment at scheduled time points. Hence, our primary endpoint of symptom relief at week 12 does not necessarily cover the wide range of symptoms associated with IBS-D, and it cannot be used to describe a continuous clinical improvement over the treatment period.

In a clinical trial, micro-activation zeolite improved IBS-associated symptoms of abdominal discomfort with stool frequency and stool consistency to the same extent as placebo, indicating a pronounced placebo effect[10]. A recent randomized trial in 190 IBS patients[46] found some improvement for abdominal pain, discomfort and IBS severity after an 8-wk treatment with small-intestinal-release peppermint oil. However, the main outcomes including abdominal pain response or overall symptom relief were not significant when using endpoints recommended by the FDA and the EMA. Similarly, another study assessing peppermint oil treatment in IBS patients based on an IBS-SSS endpoint did not lead to a significant result[47].

In this trial, G-PUR® was administered over a period of 12 wk. The daily dose of 6 g G-PUR® was well tolerated, and there were no clinical or laboratory safety signals throughout the study. The overall rate of AEs was lower in the G-PUR® group than in the placebo group, and the low ADE rate per patient year was the same as the placebo. Although G-PUR® is an aluminum-containing substance, no elevation in serum aluminum levels were observed in patients in this trial. This is related to the fact that within the product’s mineral phases, aluminum is not mobile but tightly bound, building up the silicate mineral crystal lattice[21]. Interestingly, the proportion of patients in whom aluminum was below the reference range at the end of the study increased in the G-PUR® group. This may also be related to the ability of clinoptilolite to adsorb metal ions in the gastrointestinal tract.

Currently, various pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapeutic interventions are available for the management of IBS-D. The treatment is individualized for the patients’ needs and predominant symptoms by their physician, considering the risk-benefit ratio for each strategy. Loperamide, which was used as rescue therapy in the present trial, is often used as a first-line agent to treat diarrhea in IBS-D. However, despite its widespread clinical use, it is worth noting that loperamide is not effective against IBS-associated abdominal pain and bloating[48-50]. Similarly, eluxadoline, a mixed opioid receptor drug, can reduce visceral hypersensitivity and prolong the gastrointestinal transit time, but the effects on abdominal pain relief are modest[51,52]. In a recent meta-analysis of established traditional therapies in IBS, tricyclic antidepressants are recommended for treatment of abdominal pain, but careful dosing is warranted based on the side-effect profile[53,54].

Dietary and lifestyle changes constitute an important non-pharmacological approach in treating IBS symptoms. A recent meta-analysis showed that patients receiving a diet low in fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols in RCTs experienced a statistically significant reduction in pain and bloating compared to patients receiving a traditional diet[55]. Overall, the exclusion of foods high in fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols may reduce IBS symptoms and can be recommended to affected patients, but there is still a need for higher-quality evidence to guide management[56]. Similarly, supplements such as vitamin D have shown modest effects compared to placebo[57-59]. PCT has been shown to be an effective sorbent for gluten derived from food sources[27], which could also contribute to its supposed benefit.

In research concerning functional disorders, treatment effects are generally assessed via patient-reported outcomes, which renders the objective evaluation difficult. A strength of this study is that it was designed to meet all of the essential methodological quality criteria for functional gastrointestinal research[60], including a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind design, the use of the Rome IV criteria for enrollment, the selection of patients with moderate to severe IBS based on the IBS-SSS, the prohibition of a wide range of concomitant medications, a treatment duration of 12 wk, the use of validated symptom scores and the formal documentation of safety data. Despite the limitation of small sample size, the clinical benefit of PCT could be demonstrated in various clinically meaningful endpoints.

The gut microbiome analysis of the patients revealed a trend towards greater alpha and beta microbial diversity in the treatment group, which has been associated with a healthy gut microbiome and improved symptoms. This change has not been observed in the placebo group. Larger cohorts would be needed to identify a causal relationship to the change in abundance of a single or several bacteria species. A pilot study with 41 patients who received 3 g of zeolite or microcrystalline cellulose twice daily showed that zeolite may lower intestinal inflammation of IBS patients. A positive effect on the gut microbiome was in line with our results[10]. Alterations in gut microbiome may impact the intestinal immune, barrier and neuromuscular junction functions and cause imbalance in the bidirectionally communicating gut-brain axis. However, the exact composition of a healthy microbiome remains unclear[61,62].

In conclusion, this randomized placebo-controlled, double-blind pilot study provided evidence that the PCT product G-PUR® can be used safely over a prolonged period of 12 wk for the treatment of patients with IBS-D. A favorable result of G-PUR® was detectable for some symptoms of IBS, i.e. abdominal pain and stool consistency. Further, a lower use of rescue medication in the G-PUR® group than in the placebo group and a trend towards greater microbial diversity generally associated with a healthy gut microbiome was observed.

Irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea (IBS-D) is a highly prevalent chronic gastrointestinal disorder with a substantial impact on quality of life. Despite the advancements in the available treatment, there is a need for effective therapy options with a favorable safety profile.

Previous studies have shown positive effects of clinoptilolite-tuff G-PUR® in multiple indications, especially for its adsorption capacity for a variety of toxins, heavy metals and other undesirable substances. Thus, clinoptilolite-tuff might be an effective therapy in IBS-D.

The primary objective of this clinical investigation was to assess the relief from IBS-D symptoms after a 12-wk treatment with G-PUR®. The main secondary objectives were to assess the safety and tolerability of treatment with G-PUR®, the impact of treatment on IBS-related symptoms, quality of life and additional exploratory parameters including microbiome analysis.

We performed a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind pilot study on 30 patients with IBS-D. Over a treatment period of 12 wk, 14 patients received 2 g of G-PUR® three times daily, and 16 patients received placebo. The response was assessed with validated IBS-D associated symptom questionnaires. Exploratory biomarkers and microbiome data were collected and analyzed.

After 12 wk of treatment, the proportions of Subject’s Guide of Assessment of Relief responders were comparable in both groups, while after 4 wk of treatment significantly more patients in the G-PUR® group vs placebo group reported complete or considerable relief. An improvement in daily abdominal pain, diarrhea-free days, abdominal pain and stool consistency response was seen in the G-PUR® group compared to the placebo group.

In this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, the purified clinoptilolite-tuff product G-PUR® demonstrated safety and clinical benefit towards some symptoms of IBS-D, representing a promising novel treatment option for these patients.

Further research is needed to evaluate clinical efficacy of clinoptilolite-tuff product G-PUR® in larger cohorts.

We thank myBioma GmbH for the microbiome analyses and designing the corresponding figures for the manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Austria

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Belkova N, Russia; Ng QX, Singapore; Qin Z, China S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Fan JR

| 1. | Drossman DA, Hasler WL. Rome IV-Functional GI Disorders: Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1257-1261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 731] [Cited by in RCA: 1034] [Article Influence: 114.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mearin F, Lacy BE, Chang L, Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Simren M, Spiller R. Bowel Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1781] [Cited by in RCA: 1896] [Article Influence: 210.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 3. | Kim YS, Kim N. Sex-Gender Differences in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;24:544-558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 27.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tanaka Y, Kanazawa M, Fukudo S, Drossman DA. Biopsychosocial model of irritable bowel syndrome. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;17:131-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Engel GL. The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. Am J Psychiatry. 1980;137:535-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1699] [Cited by in RCA: 1310] [Article Influence: 29.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ng QX, Soh AYS, Loke W, Lim DY, Yeo WS. The role of inflammation in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). J Inflamm Res. 2018;11:345-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 241] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 30.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 7. | Chang FY, Lu CL, Chen CY, Luo JC. Efficacy of dioctahedral smectite in treating patients of diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:2266-2272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cheung KH, Yuen WL. Treatment of Acute Diarrhoea in Adults with Dioctahedral Smectite (Smecta): A Prospective Randomised Study. Hong Kong J Emer Med. 2006;13:84-89. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tack JF, Miner PB Jr, Fischer L, Harris MS. Randomised clinical trial: the safety and efficacy of AST-120 in non-constipating irritable bowel syndrome - a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:868-877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Petkov V, Schütz B, Eisenwagen S, Muss C, Mosgoeller W. PMA-zeolite can modulate inflammation associated markers in irritable bowel disease - an explorative randomized, double blinded, controlled pilot trial. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2021;42:1-12. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Ducrotte P, Dapoigny M, Bonaz B, Siproudhis L. Symptomatic efficacy of beidellitic montmorillonite in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized, controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:435-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Laurino C, Palmieri B. Zeolite: "The magic stone"; Main nutritional, environmental, experimental and clinical fields of application. Nutr Hosp. 2015;32:573-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mastinu A, Kumar A, Maccarinelli G, Bonini SA, Premoli M, Aria F, Gianoncelli A, Memo M. Zeolite Clinoptilolite: Therapeutic Virtues of an Ancient Mineral. Molecules. 2019;24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lamprecht J, Ellis S, Snyman J, Laurens I. The effects of an artificially enhanced clinoptilolite in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. South Afr Fam Prac. 2017;59:18-22. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Rodriguez-Fuentes G, Denis A, Álvarez B, Iraizoz A. Antacid drug based on purified natural clinoptilolite. Micro Mesop Material. 2006;94:200-207. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Potgieter W, Samuels CS, Snyman JR. Potentiated clinoptilolite: artificially enhanced aluminosilicate reduces symptoms associated with endoscopically negative gastroesophageal reflux disease and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug induced gastritis. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2014;7:215-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gandy JJ, Laurens I, Snyman JR. Potentiated clinoptilolite reduces signs and symptoms associated with veisalgia. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2015;8:271-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lamprecht M, Bogner S, Steinbauer K, Schuetz B, Greilberger JF, Leber B, Wagner B, Zinser E, Petek T, Wallner-Liebmann S, Oberwinkler T, Bachl N, Schippinger G. Effects of zeolite supplementation on parameters of intestinal barrier integrity, inflammation, redoxbiology and performance in aerobically trained subjects. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2015;12:40. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kloppers JR. A andomized controlled trial of Absorbatox™ C35 in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A pilot study. Institutional Repository of the North-West University 2008. |

| 20. | Drossman DA. Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: History, Pathophysiology, Clinical Features and Rome IV. Gastroenterology. 2016;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1366] [Cited by in RCA: 1386] [Article Influence: 154.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Tschegg C, Rice AHN, Grasemann B, Matiasek E, Kobulej P, Dzivák M, Berger T. Petrogenesis of a Large-Scale Miocene Zeolite Tuff in the Eastern Slovak Republic: The Nižný Hrabovec Open-Pit Clinoptilolite Mine. Econo Geolo. 2019;114:1177-1194. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 22. | Tschegg C, Hou Z, Rice AHN, Fendrych J, Matiasek E, Berger T, Grasemann B. Fault zone structures and strain localization in clinoptilolite-tuff (Nižný Hrabovec, Slovak Republic). J Structural Geology. 2020;138:104090. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 23. | Deinsberger J, Marquart E, Nizet S, Meisslitzer C, Tschegg C, Uspenska K, Gouya G, Niederdöckl J, Freissmuth M, Wolzt M, Weber B. Topically administered purified clinoptilolite-tuff for the treatment of cutaneous wounds: A prospective, andomized phase I clinical trial. Wound Repair Regen. 2022;30:198-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Samekova K, Firbas C, Irrgeher J, Opper C, Prohaska T, Retzmann A, Tschegg C, Meisslitzer C, Tchaikovsky A, Gouya G, Freissmuth M, Wolzt M. Concomitant oral intake of purified clinoptilolite tuff (G-PUR) reduces enteral lead uptake in healthy humans. Sci Rep. 2021;11:14796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Glock G. Inventor VALUE PRIVATSTIFTUNG, assignee. Method for removal of heavy metals. United States Patent US8173101B2; 2012. |

| 26. | Haemmerle MM, Fendrych J, Matiasek E, Tschegg C. Adsorption and Release Characteristics of Purified and Non-Purified Clinoptilolite Tuffs towards Health-Relevant Heavy Metals. Crystals. 2021;11:1343. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ranftler C, Röhrich A, Sparer A, Tschegg C, Nagl D. Purified Clinoptilolite-Tuff as an Efficient Sorbent for Gluten Derived from Food. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ranftler C, Nagl D, Sparer A, Röhrich A, Freissmuth M, El-Kasaby A, Nasrollahi Shirazi S, Koban F, Tschegg C, Nizet S. Binding and neutralization of C. difficile toxins A and B by purified clinoptilolite-tuff. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0252211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | EMA CfMPfHuC. Guideline on the evaluation of medicinal products for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. CPMP/EWP/785/97 Rev.1. [cited 25 September 2014]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-evaluation-medicinal-products-treatment-irritable-bowel-syndrome-revision-1_en.pdf. |

| 30. | FDA. Guidance for Industry Irritable Bowel Syndrome—Clinical Evaluation of Drugs for Treatment, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). May 2012. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/78622/download. |

| 31. | Müller-Lissner S, Koch G, Talley NJ, Drossman D, Rueegg P, Dunger-Baldauf C, Lefkowitz M. Subject's Global Assessment of Relief: an appropriate method to assess the impact of treatment on irritable bowel syndrome-related symptoms in clinical trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:310-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Blake MR, Raker JM, Whelan K. Validity and reliability of the Bristol Stool Form Scale in healthy adults and patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:693-703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 300] [Article Influence: 33.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Francis CY, Morris J, Whorwell PJ. The irritable bowel severity scoring system: a simple method of monitoring irritable bowel syndrome and its progress. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:395-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 973] [Cited by in RCA: 1223] [Article Influence: 43.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 34. | Morfeld M, Kirchberger I, Bullinger M. SF-36 Fragebogen zum Gesundheitszustand: Deutsche Version des Short Form-36 Health Survey. 2., ergänzte und überarbeitete Auflage ed: Hogrefe-Verlag, 2011: 1-221. |

| 35. | Herrmann-Lingen C, Buss U, Snaith RP. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Deutsche Version (HADS-D). [cited 25 October 2022]. Available from: https://www.testzentrale.de/shop/hospital-anxiety-and-depression-scale-deutsche-version-69320.html. |

| 36. | Fliege H, Rose M, Arck P, Levenstein S, Klapp BF. Validierung des “Perceived Stress Questionnaire“ (PSQ) an einer deutschen Stichprobe. Diagnostica. 2001;47:142-152. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Moser G, Trägner S, Gajowniczek EE, Mikulits A, Michalski M, Kazemi-Shirazi L, Kulnigg-Dabsch S, Führer M, Ponocny-Seliger E, Dejaco C, Miehsler W. Long-term success of GUT-directed group hypnosis for patients with refractory irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:602-609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Nutri-Science, GmbH. Freiburger. Ernährungsprotokoll. [cited 25 October 2022]. Available from: https://www.ernaehrung.de/static/pdf/freiburger-ernaehrungsprotokoll.pdf. |

| 39. | WHO. Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) – Analysis Guide. [cited 25 October 2022]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/global-physical-activity-questionnaire. |

| 40. | Immundiagnostik AG. IDK®IDO activity ELISA, 2021. [cited 25 October 2022]. Available from: https://www.immundiagnostik.com/en/testkits/k-7726. |

| 41. | Immundiagnostik AG. IDK®Zonulin (Serum) ELISA, 2021. [cited 25 October 2022]. Available from: https://www.immundiagnostik.com/en/testkits/k-5601. |

| 42. | Immundiagnostik AG. IDK®Bile Acids (Stool), photometric, 2021. [cited 25 October 2022]. Available from: https://www.immundiagnostik.com/en/testkits/k-7878w. |

| 43. | Immundiagnostik AG. β-Defensin 2 ELISA, 2021. [cited 25 October 2022]. Available from: https://www.immundiagnostik.com/en/testkits/k-6500. |

| 44. | Immundiagnostik AG. IDK® Gluten Fecal ELISA, 2021. [cited 25 October 2022]. Available from: https://www.immundiagnostik.com/de/testkits/kt-5739. |

| 45. | Immundiagnostik AG. IDK® Zonulin (Stuhl) ELISA, 2021. [cited 25 October 2022]. Available from: https://www.immundiagnostik.com/de/testkits/k-5600. |

| 46. | Weerts ZZRM, Masclee AAM, Witteman BJM, Clemens CHM, Winkens B, Brouwers JRBJ, Frijlink HW, Muris JWM, De Wit NJ, Essers BAB, Tack J, Snijkers JTW, Bours AMH, de Ruiter-van der Ploeg AS, Jonkers DMAE, Keszthelyi D. Efficacy and Safety of Peppermint Oil in a Randomized, Double-Blind Trial of Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:123-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Nee J, Ballou S, Kelley JM, Kaptchuk TJ, Hirsch W, Katon J, Cheng V, Rangan V, Lembo A, Iturrino J. Peppermint Oil Treatment for Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:2279-2285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Efskind PS, Bernklev T, Vatn MH. A Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial with Loperamide in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:463-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Kaplan MA, Prior MJ, Ash RR, McKonly KI, Helzner EC, Nelson EB. Loperamide-simethicone vs loperamide alone, simethicone alone, and placebo in the treatment of acute diarrhea with gas-related abdominal discomfort. A randomized controlled trial. Arch Fam Med. 1999;8:243-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Cann PA, Read NW, Holdsworth CD, Barends D. Role of loperamide and placebo in management of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Dig Dis Sci. 1984;29:239-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Lembo AJ, Lacy BE, Zuckerman MJ, Schey R, Dove LS, Andrae DA, Davenport JM, McIntyre G, Lopez R, Turner L, Covington PS. Eluxadoline for Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Diarrhea. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:242-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 25.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Brenner DM, Sayuk GS, Gutman CR, Jo E, Elmes SJR, Liu LWC, Cash BD. Efficacy and Safety of Eluxadoline in Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome With Diarrhea Who Report Inadequate Symptom Control With Loperamide: RELIEF Phase 4 Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:1502-1511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Fadgyas Stanculete M, Dumitrascu DL, Drossman D. Neuromodulators in the Brain-Gut Axis: their Role in the Therapy of the Irritable Bowel Syndrome. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2021;30:517-525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Black CJ, Yuan Y, Selinger CP, Camilleri M, Quigley EMM, Moayyedi P, Ford AC. Efficacy of soluble fibre, antispasmodic drugs, and gut-brain neuromodulators in irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:117-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Altobelli E, Del Negro V, Angeletti PM, Latella G. Low-FODMAP Diet Improves Irritable Bowel Syndrome Symptoms: A Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2017;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Black CJ, Ford AC. Best management of irritable bowel syndrome. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2021;12:303-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Chong RIH, Yaow CYL, Loh CYL, Teoh SE, Masuda Y, Ng WK, Lim YL, Ng QX. Vitamin D supplementation for irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;37:993-1003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Huang H, Lu L, Chen Y, Zeng Y, Xu C. The efficacy of vitamin D supplementation for irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Nutr J. 2022;21:24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Abuelazm M, Muhammad S, Gamal M, Labieb F, Amin MA, Abdelazeem B, Brašić JR. The Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation on the Severity of Symptoms and the Quality of Life in Irritable Bowel Syndrome Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients. 2022;14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Ford AC, Vandvik PO. Irritable bowel syndrome. BMJ Clin Evid. 2012;2012. [PubMed] |

| 61. | Chong PP, Chin VK, Looi CY, Wong WF, Madhavan P, Yong VC. The Microbiome and Irritable Bowel Syndrome - A Review on the Pathophysiology, Current Research and Future Therapy. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 30.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Asha MZ, Khalil SFH. Efficacy and Safety of Probiotics, Prebiotics and Synbiotics in the Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2020;20:e13-e24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |