Published online Sep 7, 2022. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v28.i33.4861

Peer-review started: January 19, 2022

First decision: April 10, 2022

Revised: April 19, 2022

Accepted: August 6, 2022

Article in press: August 6, 2022

Published online: September 7, 2022

Processing time: 223 Days and 22.1 Hours

The Rome IV criteria eliminated abdominal discomfort for irritable bowel syn

To compare bowel symptoms and psychosocial features in IBS patients diagnosed with Rome III criteria with abdominal discomfort, abdominal pain, and pain & discomfort.

We studied IBS patients meeting Rome III criteria. We administered the IBS symptom ques

Of the 367 Rome III IBS patients enrolled, 33.8% (124 cases) failed to meet Rome IV criteria for an IBS diagnosis. There were no meaningful differences between the pain group (n = 233) and the discomfort group (n = 83) for the following: (1) Frequency of defecatory abdominal pain or discomfort; (2) Bowel habits; (3) Coexisting extragastrointestinal pain; (4) Comorbid anxiety and depression; and (5) IBS quality of life scores except more patients in the discomfort group reported mild symptom than the pain group (22.9% vs 9.0%). There is a significant tendency for patients to report their defecatory and non-defecatory abdominal symptom as pain alone, or discomfort alone, or pain & discomfort (all P < 0.001).

IBS patients with abdominal discomfort have similar bowel symptoms and psychosocial features to those with abdominal pain. IBS symptoms manifesting abdominal pain or discomfort may primarily be due to different sensation and reporting experience.

Core Tip: It is generally accepted that abdominal pain is the most predominant symptom of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and Rome IV eliminated abdominal discomfort as diagnostic criteria for IBS. Asian studies showed about one-third of IBS patients diagnosed using Rome III criteria had abdominal discomfort alone. In this study, we compared bowel symptoms, extraintestinal symptoms, IBS-quality of life, psychological status and healthcare-seeking behaviors, and efficacy between the abdominal pain and abdominal discomfort groups expecting to find a difference between the two groups but did not. We also assessed risk factors for symptom reporting for IBS patients.

- Citation: Fang XC, Fan WJ, Drossman DD, Han SM, Ke MY. Are bowel symptoms and psychosocial features different in irritable bowel syndrome patients with abdominal discomfort compared to abdominal pain? World J Gastroenterol 2022; 28(33): 4861-4874

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v28/i33/4861.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v28.i33.4861

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common functional bowel disorder with a global prevalence of 4.1% according to the Rome IV criteria and 10.1% with Rome III criteria[1]. Using the Rome III definition, IBS is characterized by recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort associated with altered bowel frequency or stool form[2]. However, the term “discomfort” was deleted from the 2016 Rome IV diagnostic criteria because some languages do not have a word for discomfort or it has different meanings in different languages or cultures[3,4]. Possibly abdominal discomfort has qualitative and quantitative levels of distinction with abdominal pain[5]. The data from a population-based survey of adults in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom showed that eliminating “discomfort” from the criteria for IBS affected diagnostic rates only slightly[6], and only 10% of Rome III-IBS patients among the Swedish cohort did not fulfill Rome-IV IBS diagnosis due to reporting only abdominal discomfort and not pain[7]. However, clinical studies from Thailand and central China revealed that about one-third of patients with IBS diagnosed using Rome III criteria had abdominal discomfort alone[8,9]. This rate is as high as 84.2% from another clinical retrospective report from Tianjin, China[10]. Evidence regarding pa

This study aimed to: (1) Compare the bowel and extraintestinal symptoms of patients with IBS presenting with abdominal discomfort alone to those with pain alone as well as with pain & discomfort; (2) Evaluate the anxiety, depression, quality of life (QOL), and symptom reporting tendency for patients with pain and discomfort; and (3) Validate whether the discomfort is milder than pain on a continuum of severity for Chinese patients. The clinical data were drawn from the IBS database of Peking Union Medical College Hospital.

Consecutive patients with IBS aged 18-65 years from Peking Union Medical College Hospital gastroenterology clinics were enrolled in this study from June 2009 to February 2016. All patients met Rome III diagnostic and subtype criteria[2], including IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D), IBS with constipation (IBS-C), and mixed IBS. Patients with organic gastrointestinal diseases and metabolic diseases were excluded based on the results of routine tests for blood, urine, stool; liver, kidney, and thyroid function, measurements of carcinoembryonic antigen, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein, and abdominal ultrasound and colonoscopy/barium enema in the past year. The participating patients provided oral or written consent to participate before study enrollment. This study was approved by the Peking Union Medical College Hospital Ethics Committee (S-234).

The IBS symptom questionnaire was administered by well-trained investigators in face-to-face interviews. The questionnaire was adapted from a previous symptom-related questionnaire for adult functional gastrointestinal disorders in Beijing[13], the Rome III diagnostic questionnaire for adult functional gastrointestinal disorders, and the Rome III psychosocial alarm questionnaire for functional gastrointestinal disorders[2]. Information collected included demographic data, IBS disease course, frequency and severity of IBS symptoms, defecation-related symptoms, extraintestinal symptoms, physical examination and supplementary examination results, and IBS treatments in the whole disease course and the last year.

Patients were evaluated according to abdominal pain, abdominal discomfort, or both abdominal pain & discomfort just before defecation (pre-defecatory), at IBS onset, and between IBS symptom episodes without association to defecation (ordinary). Patients with the presence or worsening of pre-defecatory abdominal pain and without pre-defecatory abdominal discomfort were categorized as the pain group regardless of whether they had abdominal pain or discomfort during the ordinary period. Similarly, patients with pre-defecatory abdominal discomfort and without pre-defecatory abdominal pain were categorized as the discomfort group, and patients with pre-defecatory abdominal pain and discomfort were categorized as the pain & discomfort group.

The main intestinal symptom score for IBS-D was calculated according to the report by Zhu et al[14]. Diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease and functional dyspepsia were made according to the Montreal consensus[15] and Rome III diagnostic and subtype criteria[2], respectively. Patients who did not met Rome IV diagnostic criteria for IBS (including patients with pre-defecatory abdominal discomfort alone or symptom frequency < 1 d/wk) were evaluated for possible diagnoses of other functional bowel disorders using Rome IV criteria, including functional diarrhea, functional constipation, functional abdominal bloating/distension, and unspecified functional bowel disorder[3].

The simplified Chinese version of the IBS-QOL instrument was used to evaluate patient QOL[16], which was translated from IBS-QOL[17] and well validated. This instrument was completed by patients according to the instructions provided; the total score and eight domain scores were calculated as in a previous publication[14].

The Hamilton Anxiety (HAMA) and Hamilton Depression (HAMD) scales were used to evaluate patient psychological status by specially trained professionals through conversation and observation. A HAMA score ≥ 14 was judged as anxiety and ≥ 21 as moderate-to-severe anxiety. A HAMD score ≥ 17 was judged as depression and ≥ 24 as moderate-to-severe depression[18,19].

All analyses were performed using SPSS version 19.0 (IBM Corporation, Somers, NY, United States). Parametric distribution was evaluated by Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Parametric and categorical data are presented as mean ± SD or rate, respectively. Nonparametric data were presented as median and interquartile range. Comparisons among the three groups were made by one-way analysis of variance for parametric data, Kruskal-Wallis test for nonparametric data, and χ2test for categorical variables. Spearman’s test was performed to assess nonparametric correlations between two quantitative variables. Bonferroni test was used to adjust for pairwise comparison among the three groups after analysis of variance. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to determine the independent factors for abdominal pain or abdominal discomfort. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

In total, 367 patients meeting Rome III criteria for IBS were enrolled in this study (205 males and 162 females), with an average age of 43.0 ± 11.4 years.

There were 233 patients (63.5%) in the pain group, 83 patients (22.6%) in the discomfort group, and 51 patients (13.9%) in the pain & discomfort group. There were more males in the discomfort group than in the pain group (67.5% vs 50.2%, P = 0.01). There were no significant differences in age, body mass index, educational level, physical work, family economic status, marriage status, the average IBS disease course, and IBS subtype distribution among the three groups (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

| Variable | Pain group (n = 233) | Discomfort group (n = 83) | Pain & discomfort group | P value |

| Male, % | 117 (50.2) | 56 (67.5) | 32 (62.7) | 0.012 |

| Age in yr | 43.7 ± 11.7 | 42.3 ± 10.6 | 40.8 ± 11.0 | 0.23 |

| BMI in kg/m2 | 23.0 ± 4.0 | 22.8 ± 4.0 | 22.3 ± 3.8 | 0.56 |

| Education level, college and above, % | 71 (30.5) | 29 (34.9) | 13 (25.5) | 0.51 |

| Physical labor, % | 135 (57.9) | 42 (50.6) | 34 (66.7) | 0.18 |

| Family economic status, well-off & above, % | 105 (45.1) | 44 (53.0) | 18 (35.3) | 0.13 |

| Marriage status, married, % | 201 (86.3) | 71 (85.5) | 41 (80.4) | 0.56 |

| IBS disease course in yr1 | 6.0 (7.5) | 5.3 (7.0) | 6.0 (7.0) | 0.38 |

| IBS type | 0.06 | |||

| IBS-D, % | 95.7 | 96.4 | 86.3 | |

| IBS-C, % | 3.0 | 2.4 | 7.8 | |

| IBS-M, % | 1.3 | 1.2 | 5.9 |

In the three groups, the locations of abdominal pain, discomfort, or pain & discomfort before defecation were mainly in the umbilical region, lower abdomen, and left lower quadrant. There was no significant difference in distribution of symptom location, even though more patients in the discomfort group reported the symptom location as “others” (indicating varied or obscure locations) than in the pain group (21.7% vs 10.3%, P = 0.009). There was a significant difference in the severity of pain and/or discomfort among the three groups (P = 0.007), and more patients in the discomfort group reported mild symptom than those in the pain group. There was no significant difference in frequency among the three groups (Table 2).

| Variable | Pain group (n = 233) | Discomfort group (n = 83) | Pain & discomfort group (n = 51) | P value |

| Location1, % | 0.213 | |||

| Left lower quadrant | 67 (28.8) | 14 (16.9) | 12 (23.5) | |

| Umbilical | 79 (33.9) | 27 (32.5) | 20 (39.2) | |

| Lower abdomen | 65 (27.9) | 23 (27.7) | 15 (29.4) | |

| Epigastric | 11 (4.7) | 2 (2.4) | 2 (3.9) | |

| Whole abdomen | 12 (4.0) | 8 (9.6) | 5 (9.8) | |

| Others | 24 (10.3) | 18 (21.7) | 7 (13.7) | |

| Severity, % | 0.007 | |||

| Mild | 21 (9.0) | 19 (22.9) | 6 (11.7) | |

| Moderate | 160 (68.7) | 55 (66.3) | 37 (72.6) | |

| Severe | 52 (22.3) | 9 (10.8) | 8 (15.7) | |

| Frequency, % | 0.290 | |||

| 3 d/mo | 37 (15.9) | 11 (13.3) | 4 (7.84) | |

| 1 d/wk | 25 (10.7) | 5 (6.0) | 2 (3.9) | |

| >1 d/wk | 108 (46.4) | 38 (45.8) | 27 (52.94) | |

| Every day | 63 (27.0) | 29 (34.9) | 18 (35.3) | |

| Ordinary pain/discomfort, % | < 0.001 | |||

| Pain alone | 84 (36.1) | 6 (7.2) | 6 (11.8) | |

| Discomfort alone | 21 (9.0) | 43 (51.8) | 3 (5.9) | |

| Pain & discomfort | 7 (3.0) | 2 (2.4) | 28 (54.9) | |

| No pain or discomfort | 121 (51.9) | 32 (38.6) | 14 (27.4) | |

| Defecation-related symptoms, % | ||||

| Abdominal bloating | 93 (39.9) | 43 (51.8) | 35 (68.6) | 0.0013 |

| Abdominal distension | 21 (9.0) | 13(15.7) | 12 (23.5) | 0.013 |

| Urgency | 197 (84.6) | 80 (96.4) | 42 (82.4) | 0.012,4 |

| Defecation straining | 70 (30.0) | 25 (30.1) | 23 (45.1) | 0.10 |

| Sensation of anorectal obstruction | 62 (26.6) | 30 (36.1) | 19 (37.3) | 0.13 |

| Anorectal pain | 28 (12.0) | 15 (18.1) | 17 (33.3) | 0.0013 |

| Sensation of incomplete evacuation | 164 (70.4) | 74 (89.2) | 39 (76.5) | 0.0032 |

| Passing mucus | 141 (60.5) | 66 (79.5) | 39 (76.5) | 0.0022 |

There were significant differences in the prevalence of ordinary abdominal pain or/and discomfort among the three groups (P < 0.001). More patients in the pain group reported ordinary abdominal pain than those in the discomfort group and pain & discomfort group, while more patients in the discomfort group reported ordinary abdominal discomfort than those in the pain group and pain & discomfort group. In the pain & discomfort group, 54.9% of patients reported having ordinary pain and discomfort, which was significantly higher than the other two groups (Table 2).

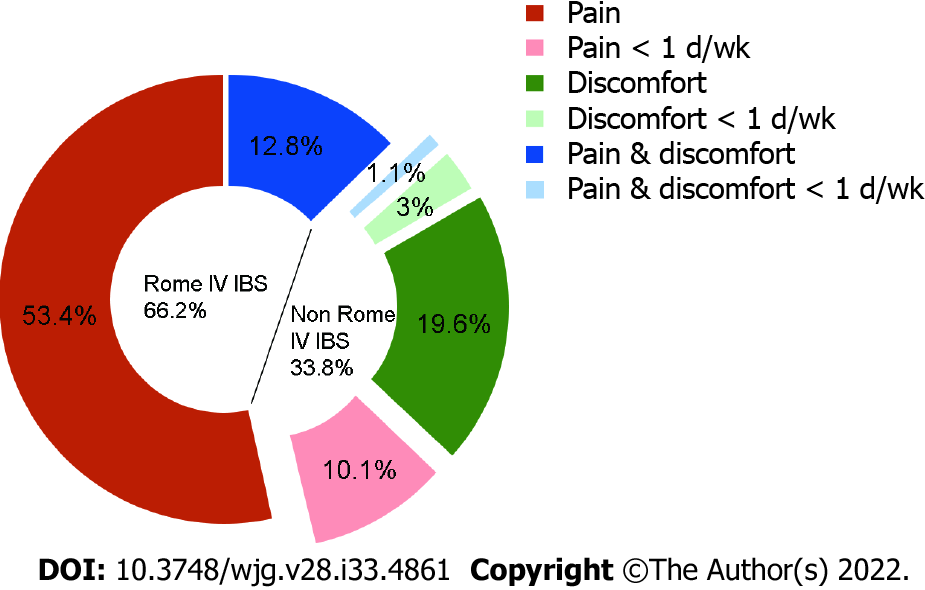

In total, there were 52 patients (14.2%) with onset frequency of < 1 d/wk (i.e. 3 d/mo), including 37 cases in the pain group, 11 cases in the discomfort group, and 4 cases in the pain & discomfort group. The proportion of less frequency was 15.9%, 13.3%, and 7.8%, respectively, without significant difference (P = 0.32). According to Rome IV diagnostic criteria, a total of 124 patients (33.8%) would not meet an IBS diagnosis (Figure 1).

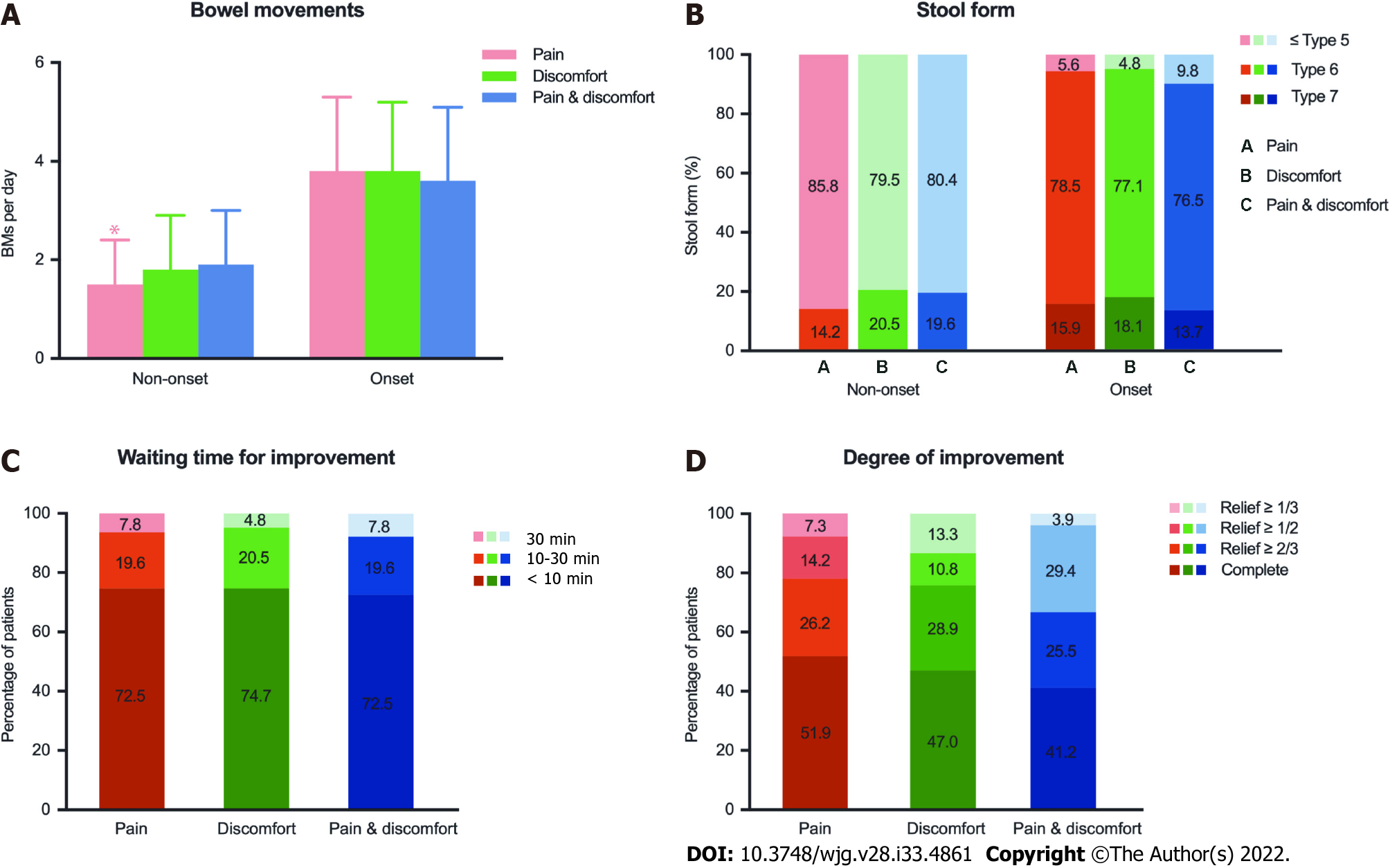

In 345 patients with IBS-D, the average bowel movements during symptom non-onset period of the pain group (1.5 ± 0.9/d) were less than the discomfort group (1.8 ± 1.1/d) and the pain & discomfort group (1.9 ± 1.1/d) (P = 0.004), but there were no significant differences in average bowel movements during symptom onset period (3.8 ± 1.5 vs 3.8 ± 1.4 vs 3.6 ± 1.5, P > 0.05) (Figure 2A). There were no significant differences in stool form during symptom non-onset and onset periods among the three groups (all P > 0.05) (Figure 2B).

Abdominal pain and/or discomfort improved after defecation except for 1 patient in the pain group. There was no significant difference in the waiting time and degree for improvement among the three groups (Figure 2C and D).

In IBS-D patients, the main intestinal symptom score was 9.3 ± 1.6 in the pain group, 9.4 ± 1.5 in the discomfort group, and 9.6 ± 1.3 in the pain & discomfort group (P > 0.05).

The prevalence of defecation related symptoms such as abdominal bloating, urgency, sensation of incomplete evacuation, and passing mucus were high overall for all 3 groups. More patients in the discomfort group reported having urgency, sensation of incomplete evacuation, and passing mucus than those in the pain group (all P < 0.05). In the pain & discomfort group, the prevalence of abdominal bloating, abdominal distension, and anorectal pain was significantly higher than that in the pain group (all P < 0.05) (Table 2).

There were no significant differences in the prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease or functional dyspepsia between the pain group and the discomfort group (P > 0.05), but the prevalence of epigastric pain syndrome, mainly epigastric pain was higher in the pain group than the discomfort group (21.0% vs 7.2%, 18.5% vs 6.0%, P < 0.05). More patients in the pain & discomfort group reported early satiation, dyspareunia, and menstrual pain for women than in the pain group (all P < 0.05). The prevalence of dyspareunia in the pain & discomfort group was also higher than in the discomfort group (P < 0.001) (Table 3).

| Variable | Pain group (n = 233) | Discomfort group (n = 83) | Pain & discomfort group (n = 51) | P value |

| GERD, % | 60 (25.8) | 14 (16.9) | 10 (19.6) | 0.20 |

| Heartburn | 35 (15.0) | 6 (7.2) | 6 (11.8) | 0.18 |

| Acid reflux | 44 (18.9) | 10 (12.1) | 5 (9.8) | 0.15 |

| Food regurgitation | 14 (6.0) | 4 (4.8) | 3 (5.9) | 0.92 |

| Retrosternal chest pain | 10 (4.3) | 3 (3.6) | 2 (3.9) | 0.96 |

| Functional dyspepsia, % | 86 (36.9) | 23 (27.7) | 18 (35.3) | 0.32 |

| Epigastric pain syndrome | 49 (21.0) | 6 (7.2) | 7 (13.7) | 0.012 |

| Epigastric pain | 43 (18.5) | 5 (6.0) | 7 (13.7) | 0.022 |

| Epigastric burning | 12 (5.2) | 2 (2.4) | 3 (5.9) | 0.54 |

| Postprandial distress syndrome | 64 (27.5) | 22 (26.5) | 15 (29.4) | 0.94 |

| Postprandial fullness | 57 (24.5) | 20 (24.1) | 9 (17.7) | 0.57 |

| Early satiation | 14 (6.0) | 6 (7.2) | 9 (17.7) | 0.023 |

| Somatic pain, % | ||||

| Headache | 17 (45.9) | 37 (44.6) | 26 (51.0) | 0.76 |

| Neck pain | 21 (9.0) | 7 (8.4) | 3 (5.9) | 0.77 |

| Backache | 41 (17.6) | 8 (9.6) | 7 (13.7) | 0.21 |

| Dyspareunia | 12 (5.2) | 6 (7.2) | 11 (21.6) | < 0.0013,4 |

| Menstrual pain1 | 30 (25.9) | 10 (37.0) | 11 (57.9) | 0.0163 |

There were no significant differences in HAMA score, HAMD score, or the prevalence and severity of anxiety and depression among the three groups (Table 4).

| Variable | Pain group (n = 233) | Discomfort group (n = 83) | Pain & discomfort group | P value | |

| HAMA score | 16.1 ± 7.3 | 15.5 ± 7.3 | 17.3 ± 7.4 | 0.36 | |

| Comorbid anxiety, % | 141 (60.5) | 49 (59.0) | 38 (74.5) | 0.14 | |

| Mild | 69 (29.6) | 25 (30.1) | 21 (41.2) | 0.26 | |

| Moderate-severe | 72 (30.9) | 24 (28.9) | 17 (33.3) | 0.86 | |

| HAMD score | 13.2 ± 6.2 | 12.3 ± 6.1 | 14.3 ± 5.5 | 0.18 | |

| Comorbid depression, % | 66 (28.3) | 22 (26.5) | 18 (35.3) | 0.53 | |

| Mild | 54 (23.2) | 20 (24.1) | 17 (33.3) | 0.31 | |

| Moderate-severe | 12 (5.2) | 2 (2.4) | 1 (2.0) | 0.40 | |

| Comorbid anxiety & depression, % | 62 (26.6) | 20 (24.1) | 18 (35.3) | 0.35 | |

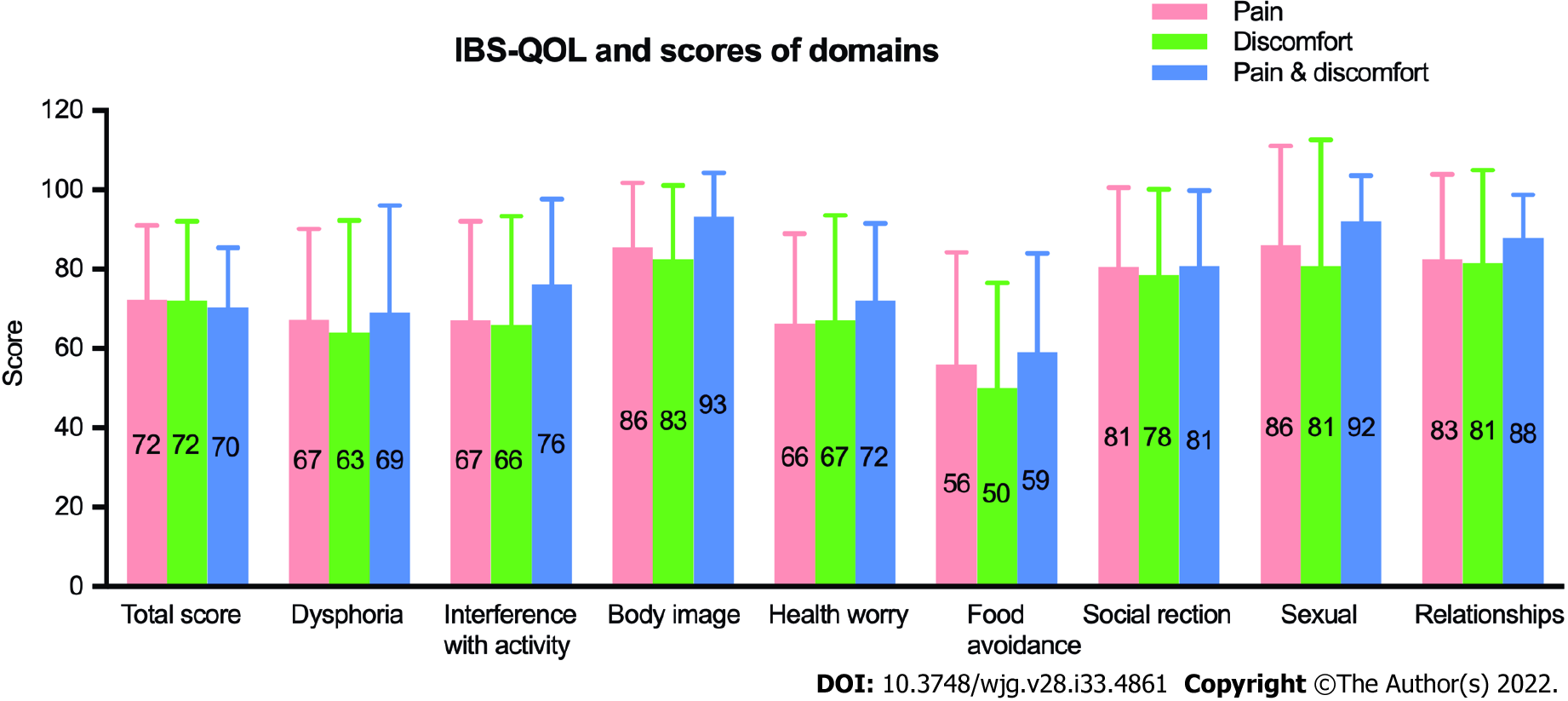

The QOL of patients with IBS showed an obvious decrease with an IBS-QOL score of 72.2 ± 17.9 in the pain group, 72.0 ± 20.0 in the discomfort group, and 70.4 ± 15.0 in the pain & discomfort group while comparing to the mean overall score in healthy Chinese subjects (95.50 ± 6.73 with the scores on each of the eight domains being ≥ 90.00)[16]. The most meaningful impairment for all 3 groups was food avoidance, following by dysphoria, interference with activity, and health worry. There were no significant differences in the eight domain scores between the pain group and discomfort group (Figure 3), while patients in the pain & discomfort group had lower QOL than patients having dis

There were no significant differences among the three groups in the average number of consultations and colonoscopies in the whole disease course and the average consultations and intermittent and long-term medication use in the last year (all P > 0.05). More patients in discomfort group used antispasmodics (muscarinic cholinergic receptor antagonists and selective intestinal calcium channel blockers), and all patients who used the antispasmodics had a reasonably good response (response rate over 50%). The overall satisfaction rate (including complete satisfaction and satisfaction) with medical care showed no significant difference among the three groups (P > 0.05) (Table 5).

| Variable | Pain group (n = 233) | Discomfort group (n = 83) | Pain & discomfort group | P value |

| In the whole disease course | ||||

| Consultation times per year1 | 4.6 ± 6.7 | 5.7 ± 6.2 | 4.2 ± 4.1 | 0.54 |

| Colonoscopies2 | 1.9 ± 1.4 | 1.5 ± 0.8 | 1.6 ± 0.9 | 0.22 |

| In the last year | ||||

| Consultation times1 | 4.0 ± 5.7 | 4.5 ± 4.5 | 4.9 ± 4.7 | 0.54 |

| Medications, intermittent and long-term use, % | 164 (70.4) | 56 (67.5) | 43 (84.3) | 0.09 |

| Antispasmodics use | ||||

| Use rate | 29 (12.4) | 24 (28.9) | 12 (23.5) | 0.0023 |

| Response rate | 22 (75.9) | 13 (54.2) | 10 (83.3) | 0.12 |

| Overall satisfaction to medical care, % | 125 (53.7) | 39 (47.0) | 21 (41.2) | 0.21 |

Twelve variables differing between the pain group and the discomfort group at a P value with significant difference in Tables 1-3 were utilized for a multiple logistic regression analysis. We found that male patients [odds ratio (OR) = 1.955, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.104-3.462, P = 0.021] and patients with mild defecatory abdominal pain or discomfort (OR = 4.020, 95%CI: 1.436-11.253, P = 0.008) were the predictors for patients to describe their pre-defecatory symptoms as abdominal discomfort alone rather than abdominal pain alone (Table 6). Similar analyses were performed between the pain group and the pain & discomfort group (11 variables) and the discomfort group and the pain & discomfort group (10 variables). We found that abdominal bloating (OR = 2.238, 95%CI: 1.080-4.638, P = 0.030) and anorectal pain (OR = 2.979, 95%CI: 1.347-6.585, P = 0.007) were the predictors for patients to describe their symptom as pain & discomfort rather than pain alone (Table 6), and no predictors were found for patients to describe their symptom as discomfort alone or pain & discomfort.

| Partial regression coefficient | Standard error | Wald χ2 | 95%CI | P value | |

| Abdominal discomfort alone vs abdominal pain alone | |||||

| Male sex | 0.671 | 0.291 | 5.293 | 1.955 (1.104-3.462) | 0.021a |

| Severity (mild defecatory pain or discomfort) | 1.391 | 0.525 | 7.018 | 4.020 (1.436-11.253) | 0.008a |

| Abdominal pain alone vs abdominal pain & discomfort | |||||

| Abdominal bloating | 0.805 | 0.372 | 4.692 | 2.238 (1.080-4.638) | 0.030a |

| Anorectal pain | 1.091 | 0.405 | 7.272 | 2.979 (1.347-6.585) | 0.007a |

Among 83 patients having pre-defecatory abdominal discomfort alone and not meeting Rome IV criteria for IBS, 48 patients (57.8%) met the diagnosis for functional diarrhea, 28 patients (33.7%) for functional abdominal bloating/distension, 2 patients (2.4%) for functional constipation, and 5 patients (6.0%) were classified as unspecified functional bowel disorder.

The present study comprehensively compared the bowel symptoms and psychosocial features of IBS patients with pre-defecatory abdominal pain alone to pre-defecatory abdominal discomfort alone, and abdominal pain & discomfort. We found that patients with abdominal discomfort had similar bowel and extraintestinal symptoms, comorbid anxiety and depression, QOL, and healthcare-seeking behaviors to those with abdominal pain.

It is generally accepted that abdominal pain is the most predominant symptom of IBS[3]; however, a previous clinical study from the United States found only 21% of IBS patients with moderate to severe symptoms reported their predominant symptom in terms of abdominal pain[11]. Another study conducted by Lembo et al[12] showed that the proportions of IBS patients who reported pain or gas (bloating-type discomfort) as one of their viscerosensory symptoms were similar (60% vs 66%). Currently, several studies compared the diagnostic rate between Rome III and IV criteria for IBS in the general population and consulting cohorts. The proportions of having abdominal discomfort varied among the western countries (2.4%-9.9%)[6,7,20,21] and the eastern countries (29.8%-84.2%)[8-10]. In this study, IBS patients with abdominal discomfort accounted for 22.6%. The elimination of abdominal discomfort from the diagnostic criteria had little effect on the diagnosis of IBS for the western countries[3], while a significant proportion of IBS patients were no longer IBS in Asian, including in China[8-10].

The significant difference between the western and eastern countries indicates there may be cultural factors that affect the experience and reporting of abdominal symptoms. The definition of abdominal pain is more uniformly accepted, while the definition for abdominal discomfort is ambiguous; “dis

Abdominal pain and discomfort are both visceral perceptions of abnormality on the same continuum with pain appearing at the more severe end of the spectrum[11]. In this study, there were no meaningful differences between the pain alone group and discomfort alone group in frequencies as well as the main intestinal symptom score for IBS-D patients except more patients in the discomfort group reported mild symptoms than the pain group. In addition, we found patients with mild defecatory abdominal pain or discomfort were predisposed to describe their pre-defecatory symptoms as abdominal discomfort alone rather than abdominal pain alone, which indicated abdominal discomfort may appear as the milder form of pain. However, it was reported that more IBS patients rank abdominal discomfort as their most bothersome symptom than abdominal pain (60% vs 29% in America[12], 15.3% vs 4.5% of IBS-C in Japan[22]), and the severity of abdominal discomfort had the strongest independent relationship with QOL impairment[10]. Patients in the three groups had similar healthcare-seeking behavior and satisfaction to medical care in this study. We speculated in terms of the symptom itself, the overall severity of IBS, and occupation of medical resources that abdominal discomfort is as important as abdominal pain.

Nevertheless, more patients in the discomfort group reported accompanying urgency, sensation of incomplete evacuation, and passing mucus than the pain group. Patients with abdominal pain & discomfort had a higher prevalence of abdominal bloating/distension and anorectal pain than patients with abdominal pain alone, and a lower score of QOL than patients with abdominal discomfort alone. In addition, we found that abdominal bloating and anorectal pain were the predictors for patients to describe their symptom as pain & discomfort rather than pain alone, suggesting coexisting symptoms played important roles in the generation of discomfort feeling.

We noticed that the previous studies seldom paid attention to the abdominal symptoms of IBS patients during non-defecatory period. An interesting finding in this study is more patients having pre-defecatory abdominal discomfort alone also reported non-defecatory abdominal discomfort than the other two groups, and a similar report tendency for patients with pain alone and pain & discomfort during defecatory period and non-defecatory period. In terms of extraintestinal symptoms, more patients in the pain group reported coexisting epigastric pain. The possible explanation for this reporting tendency is individual sensation and reporting experience to the similar stimulations and pathophysiological changes[11].

The relationships between diary stress, psychological distress, and severity of abdominal discomfort symptoms in women with IBS have been noted[23]. In this study, the scores of HAMA and HAMD and comorbid anxiety and depression were comparable between the pain group and the discomfort group. The impact of mental status to the symptom sensation and reporting could be ignored.

To date, studies on the pathophysiology of IBS mainly focused on abdominal pain[12,24-27]. As far as we know, there was no direct evidence focused on mechanism of abdominal discomfort or comparison of the difference of pathogenesis between abdominal pain and discomfort. Abdominal discomfort could simultaneously improve with abdominal pain and/or bloating to antispasmodics tiropramide and octylonium, secretagogue linaclotide, or simethicone and Bacillus coagulans for IBS or IBS-C patients[28-31]. It is unclear whether the treatments focused on bloating, diarrhea, or constipation could relieve the abdominal discomfort for those patients having defecatory abdominal discomfort alone while they are diagnosed as other bowel disorders according to Rome IV criteria (as shown in the results). Therefore, we realized that it may be more beneficial to classify patients with bowel-related abdominal discomfort into IBS from a therapeutic consideration.

There are several limitations in this study. We only included the IBS patients with typical changes of bowel habits, i.e. IBS-D and IBS-C. Therefore, some mixed IBS and IBS-unclassified patients might be missed[7,31]. We enrolled patients with Rome III criteria and did not concern the abdominal pain and discomfort during or soon after bowel movement. The proportion of Rome III suspected IBS patients with this kind of pain or discomfort was low (2.9% according to Bai et al[9]). Moreover, we did not ask patients to describe the difference between abdominal pain and discomfort. The data for response to therapies were retrospective recall, including prescription and over-the-counter. In addition, the prevalence of IBS in the general population for males was lower than females (4.1% vs 5.4%)[32], but an equal or higher ratio of male to female consulting patients was reported in clinical studies[9,14]. It is unclear whether male patients have more vigorous healthcare seeking behaviors or priority of medical care than female patients, but more female patients reported frequent consultations and colonoscopies during the whole disease course of IBS than male patients[33]. IBS-D is the predominant subtype, which accounted for 74.1% in the general population of South China[34] and 66.3% in consulting patients[31]. In addition, this was a single-center study.

Chinese patients with IBS can differentiate and report abdominal pain or/and abdominal discomfort as their key bowel symptom. The patients with abdominal discomfort had similar bowel symptoms and psychosocial features to those with abdominal pain. There is a tendency for IBS patients to report their defecatory and non-defecatory abdominal symptom as pain alone, discomfort alone, or pain and discomfort. Pre-defecatory abdominal discomfort should be considered as an important symptom for IBS patients. Further studies focused on the pathophysiology and therapeutic response (including the cultural influence) of abdominal pain and discomfort are needed.

The Rome IV criteria eliminated abdominal discomfort for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), which was previously included in the Rome III criteria. Asian studies showed the rate of IBS patients with abdominal discomfort alone was high.

There are questions as to whether IBS patients with abdominal discomfort (seen in Rome III but not Rome IV) are different from those with abdominal pain (Rome IV).

To compare the bowel and extraintestinal symptoms of patients with IBS presenting with abdominal discomfort alone to those with pain alone as well as with pain & discomfort and to evaluate the anxiety, depression, quality of life, and symptom reporting tendency for patients with pain and discomfort.

We enrolled IBS patients and collected their clinical data. Patients were classified to the pain only group, the discomfort only group, and the pain & discomfort group. We compared bowel symptoms, extraintestinal symptoms, IBS-quality of life, psychological status and healthcare-seeking behaviors, and efficacy among the three groups and tested risk factors for symptom reporting in IBS patients.

About one-third of patients meeting Rome III criteria failed to meet Rome IV criteria for an IBS diagnosis. There were no meaningful differences between the pain group and discomfort group for frequency of defecatory abdominal pain or discomfort, bowel habits, coexisting extragastrointestinal pain, comorbid anxiety and depression, and IBS-quality of life scores.

IBS patients with abdominal discomfort have similar bowel symptoms and psychosocial features to those with abdominal pain.

Further studies focused on the pathophysiology and therapeutic response (including the cultural influence) of abdominal pain and discomfort are needed.

The authors thank their colleagues in the Department of Gastroenterology, Peking Union Medical College Hospital for their contributions to the enrollment of IBS patients.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Caballero-Mateos AM, Spain; Losurdo G, Italy S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Yuan YY

| 1. | Sperber AD, Bangdiwala SI, Drossman DA, Ghoshal UC, Simren M, Tack J, Whitehead WE, Dumitrascu DL, Fang X, Fukudo S, Kellow J, Okeke E, Quigley EMM, Schmulson M, Whorwell P, Archampong T, Adibi P, Andresen V, Benninga MA, Bonaz B, Bor S, Fernandez LB, Choi SC, Corazziari ES, Francisconi C, Hani A, Lazebnik L, Lee YY, Mulak A, Rahman MM, Santos J, Setshedi M, Syam AF, Vanner S, Wong RK, Lopez-Colombo A, Costa V, Dickman R, Kanazawa M, Keshteli AH, Khatun R, Maleki I, Poitras P, Pratap N, Stefanyuk O, Thomson S, Zeevenhooven J, Palsson OS. Worldwide Prevalence and Burden of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders, Results of Rome Foundation Global Study. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:99-114.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1325] [Cited by in RCA: 1198] [Article Influence: 299.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Delvaux M. Rome III-functional gastrointestinal disorders. 3th ed. BW & A Books, inc: Durham, 2006. |

| 3. | Mearin F, Lacy BE, Chang L, Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Simren M, Spiller R. Bowel Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1781] [Cited by in RCA: 1901] [Article Influence: 211.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 4. | Fang X, Francisconi CF, Fukudo S, Gerson MJ, Kang JY, Schmulson W MJ, Sperber AD. Multicultural Aspects in Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders (FGIDs). Gastroenterology. 2016;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Spiegel BM, Bolus R, Agarwal N, Sayuk G, Harris LA, Lucak S, Esrailian E, Chey WD, Lembo A, Karsan H, Tillisch K, Talley J, Chang L. Measuring symptoms in the irritable bowel syndrome: development of a framework for clinical trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:1275-1291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Palsson OS, Whitehead W, Törnblom H, Sperber AD, Simren M. Prevalence of Rome IV Functional Bowel Disorders Among Adults in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1262-1273.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 276] [Article Influence: 55.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Aziz I, Törnblom H, Palsson OS, Whitehead WE, Simrén M. How the Change in IBS Criteria From Rome III to Rome IV Impacts on Clinical Characteristics and Key Pathophysiological Factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:1017-1025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Patcharatrakul T, Thanapirom K, Gonlachanvit S. Application of Rome III vs. Rome IV diagnostic criteria for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) in clinical practice: is the newer the better? Gastroenterology. 2017;152:S717. |

| 9. | Bai T, Xia J, Jiang Y, Cao H, Zhao Y, Zhang L, Wang H, Song J, Hou X. Comparison of the Rome IV and Rome III criteria for IBS diagnosis: A cross-sectional survey. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32:1018-1025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wang B, Zhao W, Zhao C, Jin H, Zhang L, Chen Q, Wang B. What impact do Rome IV criteria have on patients with IBS in China? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54:1433-1440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sach J, Bolus R, Fitzgerald L, Naliboff BD, Chang L, Mayer EA. Is there a difference between abdominal pain and discomfort in moderate to severe IBS patients? Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:3131-3138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lembo T, Naliboff B, Munakata J, Fullerton S, Saba L, Tung S, Schmulson M, Mayer EA. Symptoms and visceral perception in patients with pain-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1320-1326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pan G, Lu S, Ke M, Han S, Guo H, Fang X. Epidemiologic study of the irritable bowel syndrome in Beijing: stratified randomized study by cluster sampling. Chin Med J (Engl). 2000;113:35-39. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Zhu L, Huang D, Shi L, Liang L, Xu T, Chang M, Chen W, Wu D, Zhang F, Fang X. Intestinal symptoms and psychological factors jointly affect quality of life of patients with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R; Global Consensus Group. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900-20; quiz 1943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2368] [Cited by in RCA: 2456] [Article Influence: 129.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 16. | Huang WW, Zhou FS, Bushnell DM, Diakite C, Yang XH. Cultural adaptation and application of the IBS-QOL in China: a disease-specific quality-of-life questionnaire. Qual Life Res. 2007;16:991-996. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Patrick DL, Drossman DA, Frederick IO, DiCesare J, Puder KL. Quality of life in persons with irritable bowel syndrome: development and validation of a new measure. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:400-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 471] [Cited by in RCA: 554] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol. 1959;32:50-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6169] [Cited by in RCA: 6791] [Article Influence: 102.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21041] [Cited by in RCA: 22873] [Article Influence: 351.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Black CJ, Yiannakou Y, Houghton LA, Ford AC. Epidemiological, Clinical, and Psychological Characteristics of Individuals with Self-reported Irritable Bowel Syndrome Based on the Rome IV vs Rome III Criteria. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:392-398.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Vork L, Weerts ZZRM, Mujagic Z, Kruimel JW, Hesselink MAM, Muris JWM, Keszthelyi D, Jonkers DMAE, Masclee AAM. Rome III vs Rome IV criteria for irritable bowel syndrome: A comparison of clinical characteristics in a large cohort study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kanazawa M, Miwa H, Nakagawa A, Kosako M, Akiho H, Fukudo S. Abdominal bloating is the most bothersome symptom in irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C): a large population-based Internet survey in Japan. Biopsychosoc Med. 2016;10:19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hertig VL, Cain KC, Jarrett ME, Burr RL, Heitkemper MM. Daily stress and gastrointestinal symptoms in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Nurs Res. 2007;56:399-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ludidi S, Mujagic Z, Jonkers D, Keszthelyi D, Hesselink M, Kruimel J, Conchillo J, Masclee A. Markers for visceral hypersensitivity in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;26:1104-1111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Josefsson A, Rosendahl A, Jerlstad P, Näslin G, Törnblom H, Simrén M. Visceral sensitivity remains stable over time in patients with irritable bowel syndrome, but with individual fluctuations. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;31:e13603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wouters MM, Balemans D, Van Wanrooy S, Dooley J, Cibert-Goton V, Alpizar YA, Valdez-Morales EE, Nasser Y, Van Veldhoven PP, Vanbrabant W, Van der Merwe S, Mols R, Ghesquière B, Cirillo C, Kortekaas I, Carmeliet P, Peetermans WE, Vermeire S, Rutgeerts P, Augustijns P, Hellings PW, Belmans A, Vanner S, Bulmer DC, Talavera K, Vanden Berghe P, Liston A, Boeckxstaens GE. Histamine Receptor H1-Mediated Sensitization of TRPV1 Mediates Visceral Hypersensitivity and Symptoms in Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:875-87.e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 271] [Article Influence: 30.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Larsson MB, Tillisch K, Craig AD, Engström M, Labus J, Naliboff B, Lundberg P, Ström M, Mayer EA, Walter SA. Brain responses to visceral stimuli reflect visceral sensitivity thresholds in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:463-472.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Lee KN, Lee OY, Choi MG, Sohn CI, Huh KC, Park KS, Kwon JG, Kim N, Rhee PL, Myung SJ, Lee JS, Lee KJ, Park H, Lee YC, Choi SC, Jung HK, Jee SR, Choi CH, Kim GH, Park MI, Sung IK. Efficacy and Safety of Tiropramide in the Treatment of Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Multicenter, Randomized, Double-blind, Non-inferiority Trial, Compared With Octylonium. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;20:113-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Johnston JM, Kurtz CB, Macdougall JE, Lavins BJ, Currie MG, Fitch DA, O'Dea C, Baird M, Lembo AJ. Linaclotide improves abdominal pain and bowel habits in a phase IIb study of patients with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1877-1886.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 30. | Urgesi R, Casale C, Pistelli R, Rapaccini GL, de Vitis I. A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial on efficacy and safety of association of simethicone and Bacillus coagulans (Colinox®) in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2014;18:1344-1353. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Yao X, Yang YS, Cui LH, Zhao KB, Zhang ZH, Peng LH, Guo X, Sun G, Shang J, Wang WF, Feng J, Huang Q. Subtypes of irritable bowel syndrome on Rome III criteria: a multicenter study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:760-765. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Zhao Y, Zou D, Wang R, Ma X, Yan X, Man X, Gao L, Fang J, Yan H, Kang X, Yin P, Hao Y, Li Q, Dent J, Sung J, Halling K, Wernersson B, Johansson S, He J. Dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome in China: a population-based endoscopy study of prevalence and impact. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:562-572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 33. | Fan WJ, Xu D, Chang M, Zhu LM, Fei GJ, Li XQ, Fang XC. Predictors of healthcare-seeking behavior among Chinese patients with irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:7635-7643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Xiong LS, Chen MH, Chen HX, Xu AG, Wang WA, Hu PJ. A population-based epidemiologic study of irritable bowel syndrome in South China: stratified randomized study by cluster sampling. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:1217-1224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |