Published online Aug 21, 2022. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v28.i31.4390

Peer-review started: April 22, 2022

First decision: May 9, 2022

Revised: May 22, 2022

Accepted: July 25, 2022

Article in press: July 25, 2022

Published online: August 21, 2022

Processing time: 115 Days and 17.5 Hours

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) nucleos(t)ide analog (NA) therapy reduces liver disease but requires prolonged therapy to achieve hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) loss. There is limited North American real-world data using non-invasive tools for fibrosis assessment and few have compared 1st generation NA or lamivudine (LAM) to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF).

To assess impact of NA on virological response and fibrosis regression using liver stiffness measurement (LSM) (i.e., FibroScan®).

Retrospective, observational cohort study from the Canadian HBV Network. Data collected included demographics, NA, HBV DNA, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and LSM. Patients were HBV monoinfected patients, treatment naïve, and received 1 NA with minimum 1 year follow-up.

In 465 (median 49 years, 37% female, 35% hepatitis B e antigen+ at baseline, 84% Asian, 6% White, and 9% Black). Percentage of 64 (n = 299) received TDF and 166 were LAM-treated with similar median duration of 3.9 and 3.7 years, respectively. The mean baseline LSM was 11.2 kPa (TDF) vs 8.3 kPa (LAM) (P = 0.003). At 5-year follow-up, the mean LSM was 7.0 kPa in TDF vs 6.7 kPa in LAM (P = 0.83). There was a significant difference in fibrosis regression between groups (i.e., mean -4.2 kPa change in TDF and -1.6 kPa in LAM, P < 0.05). The last available data on treatment showed that all had normal ALT, but more TDF patients were virologically suppressed (< 10 IU/mL) (n = 170/190, 89%) vs LAM-treated (n = 35/58, 60%) (P < 0.05). None cleared HBsAg.

In this real-world North American study, approximately 5 years of NA achieves liver fibrosis regression rarely leads to HBsAg loss.

Core Tip: In summary in this real-world diverse cohort study of chronic hepatitis B patients in Canada, long-term nucleo(s)ide analog (either 1st or 2nd generation) therapy suppresses hepatitis B virus DNA and improves hepatic inflammation and liver fibrosis, as determined by non-invasive testing (i.e., transient elastography). In patients treated for up to 5 years, none achieved hepatitis B surface antigen loss (functional cure), highlighting the need for improved therapeutic strategies to reduce the life-long burden of antiviral therapy.

- Citation: Ramji A, Doucette K, Cooper C, Minuk GY, Ma M, Wong A, Wong D, Tam E, Conway B, Truong D, Wong P, Barrett L, Ko HH, Haylock-Jacobs S, Patel N, Kaplan GG, Fung S, Coffin CS. Nationwide retrospective study of hepatitis B virological response and liver stiffness improvement in 465 patients on nucleos(t)ide analogue. World J Gastroenterol 2022; 28(31): 4390-4398

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v28/i31/4390.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v28.i31.4390

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) nucleos(t)ide analog (NA) therapy is associated with fibrosis regression, reduced risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and improved clinical outcomes[1]. The ultimate goal of HBV therapy is hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) loss and considered a functional cure enabling treatment cessation, but rarely achieved with current NA. Without HBsAg clearance, stopping treatment may lead to severe viral and biochemical flares. Studies of European patients reported HBsAg loss in 20% patients after stopping long-term NA therapy. HBsAg loss among Asian virally suppressed patients was very low (< 5%) suggesting there are important differences among different groups of patients in terms of off-treatment response[2,3]. The approved 2nd generation NA, i.e., entecavir (ETV), tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) and tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) potently reduce serum viral load (HBV DNA) but they rarely achieve a functional cure despite prolonged therapy[4]. Studies in large Asian cohorts have compared the effect of NA with a low genetic barrier to drug resistance (i.e., lamivudine, LAM) to higher potency (i.e., ETV, TDF/TAF) NA on liver fibrosis regression and viral response[5]. A single centre Asian study of 124 patients treated with anti-HBV NA documented HBV DNA suppression but all had persistently detectable HBsAg, and none achieved intrahepatic viral marker reduction (i.e., HBV covalently closed circular (ccc) DNA)[5]. A large retrospective Korean study showed lower risk of death or transplantation with ETV compared to LAM but no difference in HCC risk[6]. A recent global study involving 299 centers in 24 countries investigated outcomes after 10 years of follow-up of clinical trial patients treated with ETV or alternative NA[2]. The data revealed that 5305 Chinese ETV recipients maintained virological response with lower risk of HBV-related serious adverse events including HCC. However, approximately 17% of the cohort, and similar rate in other cohorts, continued to identify HBV-related liver disease progression[5,7]. Liver disease complications have also been reported in a Korean study of 440 cirrhotic patients (mostly genotype C) after 5 years of ETV therapy, with a 15% rate of liver disease decompensation in those with > 90% treatment adherence and 41% decompensation in patients with < 90% adherence[8].

There is limited real-world data evaluating the clinical impact of 1st vs 2nd generation long-term NA therapy in North American chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients. These patients maybe characterised by greater diversity and genotype heterogeneity based on a diverse regions of origin. Disparities in access to HBV NA is a global issue. Similarly, in Canada, NA reimbursement criteria vary by provincial or territorial jurisdiction[9]. Until recently, antivirals with a high barrier to resistance such as TDF and ETV were not funded as first line therapies for CHB in two large population provincial health jurisdictions [i.e., British Columbia (BC) and Ontario (ON)][9]. In particular, there were historic differences in reimbursement criteria with LAM utilized as first line in BC and ON, and TDF historically (before 2018) only reimbursed for persons with advanced fibrosis and/or decompensated cirrhosis. In BC and ON, HBV patients could access TDF if they failed LAM, developed resistance or very rarely, had intolerance to LAM. In this retrospective, multi-centre cohort study of 465 CHB patients followed in 8 provinces across Canada, we aim to assess HBV viral response, biochemical remission, liver fibrosis regression and HBsAg sero-clearance after treatment with median 4 years of either a 1st or 2nd line NA therapy.

This was a retrospective observational cohort study, utilizing the Canadian Hepatitis B Network cohort data from January 1st, 2012-December 1st, 2019. Participating clinics provided data from electronic and/or paper charts. De-identified information was entered into a registry REDCap® database housed at the University of Calgary (U of C) under an approved U of C Conjoint Ethics Research Board (CHREB) protocol (Ethics ID # REB16-0041), and appropriate legal data sharing agreements[10]. Study subjects provided written informed consent to participate, or were included with a waiver of consent, according to local REB approval. Data extracted included demographics (age, sex, ethnicity), antiviral regimens, HBV DNA, hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and liver stiffness measurement (LSM) prior to and during therapy. Inclusion: Adult patients >18 years, with known chronic HBV (i.e., HBsAg persistence > 6 mo duration), HBV monoinfected, treatment naïve at baseline, and were on only a single antiviral agent for the study duration. Exclusion: Participants were excluded if they had received previous HBV therapy, had a liver transplant or were co-infected with other hepatotropic viruses (e.g., HCV and HDV) or with HIV. ETV treated patients were also excluded for direct comparison of only two antiviral drugs. Persons who had their antiviral regiment switched (includes LAM-resistant patients switching to TDF) were also excluded. All patients had a minimum of 12 mo follow-up from treatment initiation, with at least annual HBV DNA evaluation using commercial assays (i.e., sensitivity 20 IU/mL or 50 copies/mL, Abbott and/or < 20 IU/mL, Roche) and serial LSM performed using FibroScan® (Echosens, Paris, Fr). Liver fibrosis, based on Metavir staging, was classified as F0-F1 (< 7.3 kPa), F2-F3 (7.3-9.5 kPa) and F4 or cirrhosis (> 9.5 kPa)[11]. CHB management and treatment monitoring was directed by the center physician(s) and based on the Canadian consensus guidelines[12].

For all analyses, patients with missing data were excluded. Continuous data were summarized with the mean, 95% confidence interval (CI) and count (n). For comparisons between treatment groups (LAM vs TDF) at a given time point, two-tailed t test was used. Repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc test was used to compare continuous variables at different time points for each treatment group. Categorical data were summarized as proportion using mean % (n/n known). Fisher’s exact test was used for comparison between dichotomous data. A linear mixed model was used to identify change over time in a multivariable linear mixed regression analysis. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS/STAT® software, IBM SPSS Statistics 27.0.1.0 and/or GraphPad Prism 9.0.

The study population included 465 patients who were treatment naïve at baseline. The mean age was 49 (SD 12.9) years, 37% were female, and 35% were HBeAg (+) at baseline. Most were Asian (84%, n = 345) (albeit from different East and/or South-East Asian) countries, 9% Black (n = 37), and 6% White (n = 25). Patients either received TDF (n = 299, 65%) or LAM (n = 166, 35%) therapies with similar median treatment duration of 3.9 and 3.7 years, respectively. There was no difference between treatment groups in sex or ethnicity. However, TDF treated individuals were more likely to be HBeAg positive (Table 1). Historically, patients from one provincial health jurisdiction (i.e., British Columbia), only had access to TDF as first line therapy if they had cirrhosis. Thus, a greater proportion of persons in the TDF group also had advanced fibrosis (> stage F3/4) at baseline, compared to LAM (Table 1).

| LAM treated (n = 166) | TDF treated (n = 299) | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 51.6 (49.7-53.6) | 47.2 (45.7-48.6) | < 0.001c |

| Male sex | 58.4% (97/166) | 64.9% (194/299) | 0.194 |

| Ethnicity (LAM 88%, n = 147/166 known, TDF, 88% n = 266/299 known) | |||

| Asian | 85.0% (125/147) | 82.7% (220/266) | 0.582 |

| Black/African/Caribbean | 5.4% (8/147) | 10.9% (29/266) | 0.072 |

| White | 6.8% (10/147) | 5.6% (15/266) | 0.669 |

| Other | 2.7% (4/147) | 0.4% (1/266) | 0.056 |

| Laboratory | |||

| HBeAg positive | 24.1% (26/108) | 39.9% (99/248) | 0.004b |

| HBV DNA (log10 IU/mL) | 7.5 (6.7-7.7) n = 149 | 7.6 (7.5-7.8) n = 269 | 0.260 |

| ALT (IU/mL) | 74.3 (62.0-86.7) n = 139 | 87.8 (76.8-98.7) n = 264 | 0.225 |

| Mean ALT × ULN | 2.7 (2.1-3.3) n = 139 | 3.7 (2.9-4.4) n = 264 | 0.077 |

| Fibrosis (baseline) | |||

| Mean Baseline Fibrosis (kPa) | 8.3 (7.2-9.5) n = 100 | 11.2 (9.9-12.4) n = 184 | 0.003b |

| F0-F1 Fibrosis (< 7.3 kPa) | 53% (53/100) | 37.5% (69/184) | 0.013a |

| F2-F3 Fibrosis (7.3-9.5 kPa) | 25% (25/100) | 16.9% (31/184) | 0.119 |

| F4 Fibrosis (> 9.5 kPa) | 22% (22/100) | 45.7% (84/184) | < 0.001c |

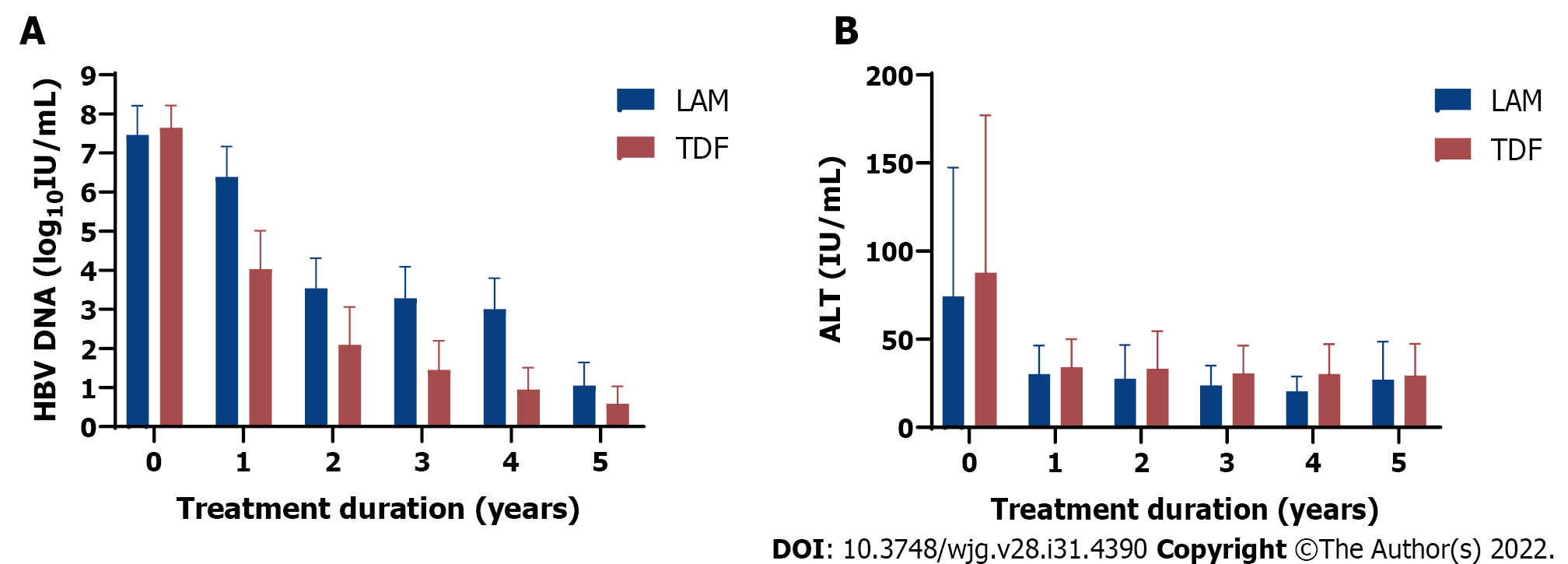

The mean baseline LSM prior to treatment was greater in TDF treated recipients (11.2 kPa, 95%CI: 9.9-12.4) than in those receiving LAM (8.3 kPa, 95%CI: 7.2-9.5) (Table 1). At baseline, serum HBV DNA and ALT levels were similar in both groups (Table 1). Compared to baseline, only TDF treated group achieved significant HBV DNA decline at 5 years follow up (p=0.0011) compared to LAM treated group (P = 0.37) (Figure 1A).

By year 5, 194/299 (64.9%) TDF patients had undetectable HBV DNA (< 10 IU/mL) than 88/166 (53.0%) LAM patients (P = 0.012, Chi-square test, Supplementary Table 1). Furthermore, a higher proportion of TDF treated patients had suppressed HBV DNA (< 10 IU/mL) (n = 170/190, 89%) vs LAM-treated (n = 35/58, 60%) (P < 0.05), but none achieved functional cure (HBsAg loss) at the end of the study period.

Both treatment groups had decline in ALT from baseline to 5-year follow-up (P = 0.014 for LAM and P < 0.0001 for TDF) (Figure 1B). As well, ALT normalization was achieved for both treatment groups by 1-year follow-up. More specifically, by year 5, 167/299 (55.9%) TDF patients achieved ALT normalization compared to 74/166 (44.6%) LAM patients (P = 0.020, Chi square test, Supplementary Table 2).

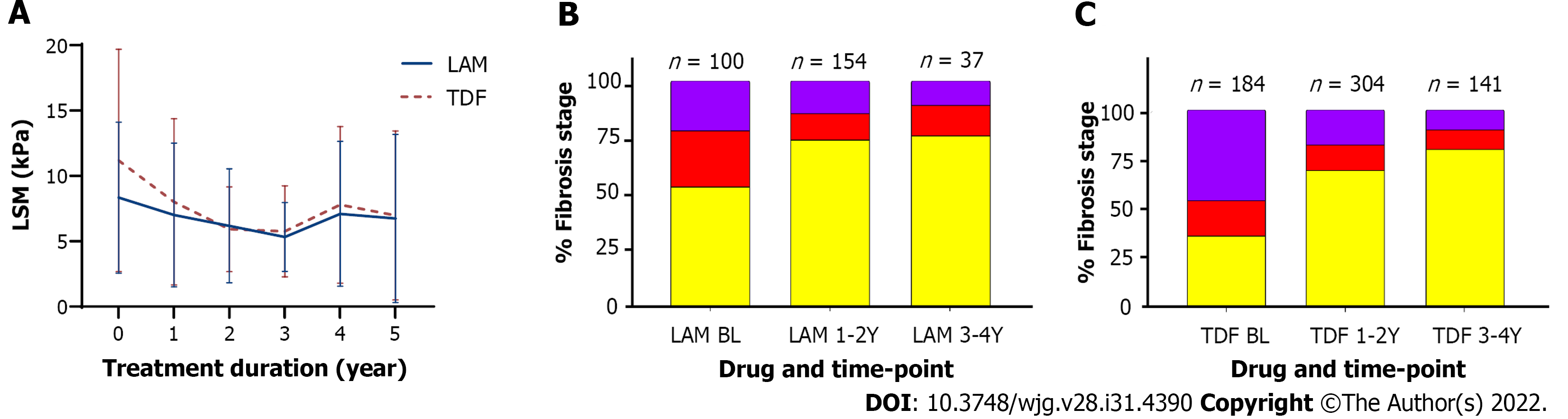

In patients with available serial long-term LSM data, NA treatment also led to improvement in liver inflammation and fibrosis regression with lower mean LSM at 5-year follow-up (7.0 kPa, 95%CI:5.8-8.2 for TDF and 6.7 kPa, 95%CI: 4.9-8.6 for LAM treated patients). Multivariable linear mixed regression with a linear mixed model showed a significant difference in fibrosis regression between antiviral treatment groups. Mean fibrosis regression was greater in TDF treated patients with -4.2 kPa change compared to -1.6 kPa in LAM recipients from baseline, P < 0.05 (Figure 2).

As well, by 4-year follow-up, LSM improved by ≥ 1 stage in 92/299 (20.8%) TDF patients compared to 29/166 (17.5%) LAM patients (P = 0.002, Chi square test).

Of the 26 HBeAg positive patients that received LAM treatment, 6 patients became HBeAg negative (23.1%). Of the 99 HBeAg positive patients that received TDF treatment, 27 patients (27.3%) achieved HBeAg loss. No data was available on LAM resistance however all patients enrolled in the study were on a single NA agent. It is standard clinical practice to switch to TDF in individuals who developed LAM resistance (and criteria for public formulary drug reimbursement in some provinces). Genotype data was not available in most patients.

In this multi-centre, retrospective real-world Canadian study, we assessed clinical outcomes in CHB patients receiving long-term NA therapy. Both 1st generation (LAM) and higher potency antivirals (TDF) reduces HBV DNA and improves liver inflammation and fibrosis based on serial LSM evaluation even after ALT normalization. This study highlights the effectiveness of both antiviral drugs in inducing fibrosis regression in a diverse HBV patient cohort. However, up to 5-year follow-up period no CHB patients achieved HBsAg loss or functional cure. A clinically relevant proportion of patients continued to show low-level viremia, especially if treated with LAM. Persons with LAM- resistance switched to TDF were not included to avoid bias of 2 different regimens. Data on antiviral resistance testing is not available, and it is likely these patients would have been switched to TDF in both BC and ON pharmacare reimbursement criteria. The clinical implications of low-level viremia, especially association with residual HCC risk is unclear and requires further study[13,14].

Many studies including randomized clinical trials, observational cohorts and meta-analyses demonstrate that NA treatment improves clinical outcomes for persons living with chronic hepatitis B[1]. Observational studies from clinical databases also reflect real-world practice and complement clinical trials[15,16]. Single centre real-world Canadian studies have observed reduced HCC risk[17]. The majority of observational studies conducted on long-term NA therapy outcomes were done in HBV-endemic countries with a particular focus on Asia. Canada is non-endemic for HBV but due to high rates of immigration from many endemic regions, CHB remains an important health issue and affects a diverse, multi-ethnic population as persons have from multiple regions and encompasses 40 countries as based on Canadian HBV Network Data. Compared to other published real-world studies, the data is also relevant/applicable in a single-payer universal health care system with equal access care albeit differences in medication re-imbursement providing for the unique aspect of this study. The Canadian health care system does provide some financial assistance to cover the cost of antiviral therapy, and other associated costs (i.e., physician visits, hospitalization, laboratory monitoring, diagnostic imaging etc.) is reimbursed by provincial health care plans.

Our study is similar to previous published work that highlights the benefits of antiviral treatment in improving liver fibrosis. A systemic review and meta-analysis including 34 published studies of treated and untreated CHB patients also found low rates of NA-induced HBsAg seroclearance, highlighting the need for improved curative therapies[18]. In fact, HBsAg seroclearance generally occurred in untreated individuals with less active disease[18], and is consistent with retrospective data from the Canadian HBV Network of CHB patients comparing outcomes in individuals that remained HBsAg positive vs those with HBsAg loss[19].

The current study is limited by retrospective data and missing data at all defined time-points, including serial lab and LSMs, and highlights the limitation of real-world studies (i.e., missed appointments, adherence and incomplete clinician documentation or reporting). We also excluded patients treated with the other approved 2nd generation NA (i.e., ETV) for purposes of the study analysis to compare a single 1st vs 2nd generation NA therapy. Moreover, although our cohort was multi-ethnic most patients were Asian, albeit individuals were born in many different east and south-east Asian countries. Additionally, there was missing ethnicity data on 52 patients (11%). Overall, this data represents immigration from up to 40 countries, based on Canadian HBV Network Data. The 2016 Canadian census reported the top Asian countries of birth for recent immigrants are Philippines, India, China, Iran, Pakistan, Syria and South Korea and Syria (www.statcan.gc.ca). There is increasing data on LSM for assessment of liver inflammation and HBV-related fibrosis, although transient elastography is not widely available in resource limited countries compared to other non-invasive fibrosis markers such as aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index (APRI) and Fibrosis4 (FIB4) calculator[20]. It is noteworthy that our analysis represents the largest North American study conducted to date on long-term follow-up with NA therapy utilizing this novel technology.

In summary in this real-world diverse cohort study of chronic hepatitis B patients in Canada, long-term nucleo(s)ide analog (either 1st or 2nd generation) therapy suppresses HBV DNA and improves hepatic inflammation and liver fibrosis, as determined by non-invasive testing (i.e., transient elastography). In patients treated for up to 5 years, none achieved HBsAg loss (functional cure), highlighting the need for improved therapeutic strategies to reduce the life-long burden of antiviral therapy.

Therapy of hepatitis B virus (HBV) with nucleos(t)ide analogues (NA) can be associated with fibrosis regression. There are both low and high potency agents approved for therapy and access to these therapies maybe variable. There is limited real-world data comparing these agents on their effect to result in fibrosis regression and long term outcomes.

Although high-potency agents are considered the standard of care, there has been variable access to these agents and indeed ongoing use of these agents in 1st world countries to include Canada. It is thus important to provide evidence in outcomes to include fibrosis regression between the high and low potency NA’s. This study may impact the use of these agents in the future, and allow consideration for switching from low to high potency agents if possible.

To assess HBV viral response, biochemical remission, liver fibrosis regression and hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) sero-clearance after treatment with either a 1st or 2nd line NA therapy. These objectives were realized and the future impact would be the consideration of utilizing 1st vs 2nd line NA’s. Further, other outcome measure to include HBsAg loss and development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) may be considered.

We performed a retrospective observational cohort study utilizing a National network in HBV. Novel aspects that allowed this study is the utilization of a National Network which was able to capture differences in NA utilization based on regional differences of reimbursement. The strength of this study lies in the diversity that the Canadian HBV Network provides. The utilization of liver stiffness by transient elastography in a North American cohort for this objective is also unique.

As per differences in utilization, a larger proportion of patients with advanced fibrosis were initiated with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) compared to LAM. At the end of the study period there were similar stages of fibrosis between the 2 groups. There was an increased fibrosis regression in those treated with a high potency compared to a low-potency NA. More patients in the TDF group also achieved virological suppression, though alanine amino transferase (ALT) normalization was similar.

In this diverse cohort treatment with low and high potency NA’s achieves high rates of viral suppression, ALT normalization and a large proportion achieve fibrosis regression. The strength of national collaboration within a network is exemplified in this study in particular taking advantages of diversity within an overall similar medical system. These differences within a Network can be a powerful tool to answer research questions and can reduce a number of biases inherent when comparing populations/studies between countries or regions.

The future direction would include potential for long-term outcomes with differential NA usage to include HBsAg loss or seroconversion and any differences in development of HCC albeit in a population with differences in stage of fibrosis at baseline. This study population and Network provides a unique perspective to answer this question.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Canada

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ferraioli G, Italy; Hua J, China S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Chen YL

| 1. | Lok AS, McMahon BJ, Brown RS Jr, Wong JB, Ahmed AT, Farah W, Almasri J, Alahdab F, Benkhadra K, Mouchli MA, Singh S, Mohamed EA, Abu Dabrh AM, Prokop LJ, Wang Z, Murad MH, Mohammed K. Antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis B viral infection in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2016;63:284-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 452] [Cited by in RCA: 425] [Article Influence: 47.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hou JL, Zhao W, Lee C, Hann HW, Peng CY, Tanwandee T, Morozov V, Klinker H, Sollano JD, Streinu-Cercel A, Cheinquer H, Xie Q, Wang YM, Wei L, Jia JD, Gong G, Han KH, Cao W, Cheng M, Tang X, Tan D, Ren H, Duan Z, Tang H, Gao Z, Chen S, Lin S, Sheng J, Chen C, Shang J, Han T, Ji Y, Niu J, Sun J, Chen Y, Cooney EL, Lim SG. Outcomes of Long-term Treatment of Chronic HBV Infection With Entecavir or Other Agents From a Randomized Trial in 24 Countries. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:457-467.e21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Liaw YF. Undesirable Long-Term Outcome of Entecavir Therapy in Chronic Hepatitis B With Cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:2146-2147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Liem KS, Fung S, Wong DK, Yim C, Noureldin S, Chen J, Feld JJ, Hansen BE, Janssen HLA. Limited sustained response after stopping nucleos(t)ide analogues in patients with chronic hepatitis B: results from a randomised controlled trial (Toronto STOP study). Gut. 2019;68:2206-2213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wong DK, Seto WK, Fung J, Ip P, Huang FY, Lai CL, Yuen MF. Reduction of hepatitis B surface antigen and covalently closed circular DNA by nucleos(t)ide analogues of different potency. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1004-10.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lim YS, Han S, Heo NY, Shim JH, Lee HC, Suh DJ. Mortality, liver transplantation, and hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with chronic hepatitis B treated with entecavir vs lamivudine. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:152-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fan R, Hou J. Reply. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:2147-2148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Shin JW, Jung SW, Lee SB, Lee BU, Park BR, Park EJ, Park NH. Medication Nonadherence Increases Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Cirrhotic Complications, and Mortality in Chronic Hepatitis B Patients Treated With Entecavir. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:998-1008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Congly SE, Brahmania M. Variable access to antiviral treatment of chronic hepatitis B in Canada: a descriptive study. CMAJ Open. 2019;7:E182-E189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Coffin CS, Ramji A, Cooper CL, Miles D, Doucette KE, Wong P, Tam E, Wong DK, Wong A, Ukabam S, Bailey RJ, Tsoi K, Conway B, Barrett L, Michalak TI, Congly SE, Minuk G, Kaita K, Kelly E, Ko HH, Janssen HLA, Uhanova J, Lethebe BC, Haylock-Jacobs S, Ma MM, Osiowy C, Fung SK; Canadian HBV Network. Epidemiologic and clinical features of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in 8 Canadian provinces: a descriptive study by the Canadian HBV Network. CMAJ Open. 2019;7:E610-E617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | de Lédinghen V, Vergniol J. Transient elastography (FibroScan). Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2008;32:58-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Coffin C, Fung S, Alvarez F. Management of Hepatitis B Virus Infection: 2018 Guidelines from the Canadian Association for the Study of Liver Disease and Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Disease Canada. Canadian Liver J. 2018;1:156-217. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kim JH, Sinn DH, Kang W, Gwak GY, Paik YH, Choi MS, Lee JH, Koh KC, Paik SW. Low-level viremia and the increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients receiving entecavir treatment. Hepatology. 2017;66:335-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kim TS, Sinn DH, Kang W, Gwak GY, Paik YH, Choi MS, Lee JH, Koh KC, Paik SW. Hepatitis B virus DNA levels and overall survival in hepatitis B-related hepatocellular carcinoma patients with low-level viremia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;34:2028-2035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kim WR, Loomba R, Berg T, Aguilar Schall RE, Yee LJ, Dinh PV, Flaherty JF, Martins EB, Therneau TM, Jacobson I, Fung S, Gurel S, Buti M, Marcellin P. Impact of long-term tenofovir disoproxil fumarate on incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Cancer. 2015;121:3631-3638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chon YE, Park JY, Myoung SM, Jung KS, Kim BK, Kim SU, Kim DY, Ahn SH, Han KH. Improvement of Liver Fibrosis after Long-Term Antiviral Therapy Assessed by Fibroscan in Chronic Hepatitis B Patients With Advanced Fibrosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:882-891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Coffin CS, Rezaeeaval M, Pang JX, Alcantara L, Klein P, Burak KW, Myers RP. The incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma is reduced in patients with chronic hepatitis B on long-term nucleos(t)ide analogue therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:1262-1269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yeo YH, Ho HJ, Yang HI, Tseng TC, Hosaka T, Trinh HN, Kwak MS, Park YM, Fung JYY, Buti M, Rodríguez M, Treeprasertsuk S, Preda CM, Ungtrakul T, Charatcharoenwitthaya P, Li X, Li J, Zhang J, Le MH, Wei B, Zou B, Le A, Jeong D, Chien N, Kam L, Lee CC, Riveiro-Barciela M, Istratescu D, Sriprayoon T, Chong Y, Tanwandee T, Kobayashi M, Suzuki F, Yuen MF, Lee HS, Kao JH, Lok AS, Wu CY, Nguyen MH. Factors Associated With Rates of HBsAg Seroclearance in Adults With Chronic HBV Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:635-646.e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 30.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Coffin C, Haylock-Jacobs S, Doucette K. Association between quantitative hepatitis B surface antigen levels (qHBsAg) and clinical outcomes of ethnically diverse Canadian chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients: REtrospective and prospectiVe rEAL world evidence study of CHB in Canada (REVEAL- CANADA). The Liver Meeting, Annual Meeting American Association for the Study of Liver Disease; 2021; Canada. Digital Online, 2021. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 20. | Gane EJ, Charlton MR, Mohamed R, Sollano JD, Tun KS, Pham TTT, Payawal DA, Gani RA, Muljono DH, Acharya SK, Zhuang H, Shukla A, Madan K, Saraf N, Tyagi S, Singh KR, Cua IHY, Jargalsaikhan G, Duger D, Sukeepaisarnjaroen W, Purnomo HD, Hasan I, Lesmana LA, Lesmana CRA, Kyi KP, Naing W, Ravishankar AC, Hadigal S. Asian consensus recommendations on optimizing the diagnosis and initiation of treatment of hepatitis B virus infection in resource-limited settings. J Viral Hepat. 2020;27:466-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |