Published online Jun 28, 2022. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v28.i24.2689

Peer-review started: January 15, 2022

First decision: February 7, 2022

Revised: February 21, 2022

Accepted: May 7, 2022

Article in press: May 7, 2022

Published online: June 28, 2022

Processing time: 159 Days and 18.2 Hours

Chronic inflammation due to Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection promotes gastric carcinogenesis. Tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), a key mediator of inflammation, induces cell survival or apoptosis by binding to two receptors (TNFR1 and TNFR2). TNFR1 can induce both survival and apoptosis, while TNFR2 results only in cell survival. The dysregulation of these processes may contribute to carcinogenesis.

To evaluate the effects of TNFR1 and TNFR2 downregulation in AGS cells treated with H. pylori extract on the TNF-α pathway.

AGS cell lines containing TNFR1 and TNFR2 receptors downregulated by specific shRNAs and nonsilenced AGS cells were treated with H. pylori extract for 6 h. Subsequently, quantitative polymerase chain reaction with TaqMan® assays was used for the relative quantification of the mRNAs (TNFA, TNFR1, TNFR2, TRADD, TRAF2, CFLIP, NFKB1, NFKB2, CASP8, CASP3) and miRNAs (miR-19a, miR-34a, miR-103a, miR-130a, miR-181c) related to the TNF-α signalling pathway. Flow cytometry was employed for cell cycle analysis and apoptosis assays.

In nonsilenced AGS cells, H. pylori extract treatment increased the expression of genes involved in cell survival and inhibited both apoptosis (NFKB1, NFKB2 and CFLIP) and the TNFR1 receptor. TNFR1 downregulation significantly decreased the expression of the TRADD and CFLIP genes, although no change was observed in the cellular process or miRNA expression. In contrast, TNFR2 downregulation decreased the expression of the TRADD and TRAF2 genes, which are both important downstream mediators of the TNFR1-mediated pathway, as well as that of the NFKB1 and CFLIP genes, while upregulating the expression of miR-19a and miR-34a. Consequently, a reduction in the number of cells in the G0/G1 phase and an increase in the number of cells in the S phase were observed, as well as the promotion of early apoptosis.

Our findings mainly highlight the important role of TNFR2 in the TNF-α pathway in gastric cancer, indicating that silencing it can reduce the expression of survival and anti-apoptotic genes.

Core Tip: This study demonstrated for the first time the effect of TNFR1 and TNFR2 downregulation on an AGS cell line treated with Helicobacter pylori extract. Although TNFR1 downregulation did not promote significant changes in the expression of mRNA and miRNAs of the tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) signalling pathway, TNFR2 downregulation promoted important changes in the signalling mediators evaluated. We observed a reduction in the expression of cell survival and anti-apoptotic genes and an increase in the expression of miR-19a and miR-34a, which affected cell cycle kinetics and contributed to early apoptosis. Thus, our findings highlight the important role of TNFR2 in the TNF-α signalling pathway in gastric carcinogenesis.

- Citation: Rossi AFT, da Silva Manoel-Caetano F, Biselli JM, Cabral ÁS, Saiki MFC, Ribeiro ML, Silva AE. Downregulation of TNFR2 decreases survival gene expression, promotes apoptosis and affects the cell cycle of gastric cancer cells. World J Gastroenterol 2022; 28(24): 2689-2704

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v28/i24/2689.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v28.i24.2689

Gastric cancer (GC) has high rates of incidence and mortality worldwide, especially in Eastern Asia, Eastern Europe and Latin America[1]. In Brazil, it is the fourth most common cancer in men and the sixth most common in women[2]. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is the main risk factor for the development of gastric neoplasms, since it is responsible for chronic inflammation in the gastric mucosa and for the GC progression cascade[3]. Consequently, it can trigger the host’s immune response, which leads to changes in the expression of genes related to inflammation, cell kinetic regulation and miRNAs[4-6]. After infection by this bacterium, tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) stands out among the mediators of inflammation and is considered to be a key mediator linking inflammation and cancer[7,8].

TNF-α is a pleiotropic proinflammatory cytokine that is important in the signalling and regulation of multiple cellular responses and processes, such as the production of other inflammatory cytokines, and cell communication, survival, proliferation and apoptosis[9]. These different functions are accomplished due to the ability of TNF-α to bind to TNFR1 (TNFRSF1A) or TNFR2 (TNFRSF1B) receptors, thus resulting in different cellular processes. Both receptors are transmembrane proteins, and although they are largely similar in terms of extracellular structure, their intracellular domains are different, and thus dictate the cellular fate for either survival or death. Though only TNFR1 has a death domain, the TNF-α signalling pathway triggered by this receptor is able to induce both cell survival and apoptosis, while TNFR2 results only in cell survival[10,11]. The signalling cascade after TNF-α/TNFR1 binding that results in cell survival starts with the recruitment of TRADD and is mediated by activation of nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-κB) and transcription of pro-survival and anti-apoptotic genes, such as cellular inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (cIAP), TRAF2 and cFLIP, and of inflammatory cytokines. However, this signal complex is transient; TNF-α rapidly dissociates from TNFR1 and binds to the Fas-associated death domain protein to form another signal complex, which coordinates downstream signalling of the caspase cascade and apoptosis. Conversely, as TNFR2 does not have a death domain, it induces long-lasting NF-kB activation by recruiting existing cytoplasmic TRAF-2/cIAP-1/cIAP-2 complexes that can inhibit pro-apoptotic factors and maintain cell survival and proliferation[9-12].

Regulation of signal transduction triggered by TNF-α requires a constant balance between the opposing functions of cell survival and cell death to maintain homeostasis. Thus, an imbalance in these processes due to changes in the expression of receptors, downstream genes, ligands and pro-/anti-apoptotic mediators may support the tumorigenic process[13]. A recent study by our research group showed dysregulation in the TNF-α signalling pathway in GC samples with an upregulation of cell survival-related genes and of TNFR2 expression, thus suggesting a prominent protumor role by TNA-α/TNFR2 binding in gastric neoplasm[14]. Furthermore, we showed through a miRNA:mRNA interaction network that this signalling pathway can be regulated by miRNAs. In addition, H. pylori infection was also associated with an increased expression of TNF-α mRNA and protein, and dysregulated miRNA expression in chronic gastritis patients. The expression pattern of these genes/miRNAs was normalized after treatment to eradicate bacteria, indicating that this pathogen influences the host’s inflammatory response in part by its action on miRNAs[6].

In accordance with our previous results, we thought it was important to evaluate the effect of silencing TNFR1 and TNFR2 receptors in an AGS gastric cell line after treatment with an H. pylori extract on TNF-α mRNA expression and on downstream genes related to its signalling pathway (TRADD, TRAF2, CFLIP, NFKB1, NFKB2, CASP8 and CASP3). In addition, we also investigated the same miRNAs previously studied (miR-19a, miR-34a, miR-103a, miR-130a and miR-181c)[14], as well as the cell cycle and apoptosis. Overall, our results highlight the main role of the TNFR2 in TNF-α signalling in an AGS cell line, while treatment with H. pylori extract induces prosurvival gene expression mainly through TNFR1.

AGS GC cells from the Cell Bank of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (BCRJ code 0311) were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in HAM-F10 medium (Cultilab, SP, Brazil) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum and 1× antibiotic/antimycotic (Gibco, Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, United States). The culture medium was replaced every two to three days. The HGC-27 GC cell line, provided by Dr Marcelo Lima Ribeiro (São Francisco University-USF, SP, Brazil), was also used in early experiments as an alternative line for follow-up experiments, and 293T cells of human embryonic kidney were provided by Dr Luisa Lina Villa (University of São Paulo–USP, SP, Brazil) for transfection experiments. The cells were maintained under the same conditions as the AGS cell line except for the culture medium, which was Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (Gibco, Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, United States). Stable shRNA-expressing cell lines with reduced expression of TNFR1 (called shTNFR1) and TNFR2 (called shTNFR2) were kept in a similar culture medium to the nonsilenced AGS cells, and further supplemented with 0.5 μg/mL puromycin or 200 μg/mL G418, respectively.

The previously described H. pylori Tox+ strain (cagA+/vacA s1m1) was grown in a selective medium (pylori-Gelose; BioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France) at 37 °C under microaerophilic conditions[15]. This strain is not resistant to any antibiotic used to treat H. pylori. H. pylori extract was prepared according to the protocol described by Li et al[16]. In brief, the H. pylori Tox+ strain was harvested and suspended in distilled water at a concentration of 2 × 108 CFU/mL. Next, the suspension was incubated at room temperature for 40 min and centrifuged at 20000 g for 20 min. The supernatant was filtered using a 0.2 mm filter and stored at -20 °C until use. The extract was tested several times (4, 6 and 24 h) using differing H. pylori extract volumes (50, 100, 150 and 200 μL) to verify the best experimental conditions. Then, 2 × 105 nonsilenced AGS cells and AGS cells with downregulation of TNFR1 (shTNFR1) and TNFR2 (shTNFR2) were seeded in 12-well plates. After 48 h, the medium was replaced with 500 μL of HAM-F10 containing 30% v/v H. pylori extract or the same proportion of water (control). Cells were incubated with H. pylori extract for 6 h in an incubator at 37 °C. For all experiments, three temporally independent events were performed.

MTT ([3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide]) assays (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States) were employed to evaluate the viability of silenced and nonsilenced AGS cells after different treatment conditions with H. pylori extract (times and H. pylori extract volumes). In summary, the culture medium was removed, and 300 μL of fresh medium containing 1 mg/mL MTT reagent was added to each well. After 30 min of incubation at 37 °C, the medium with MTT reagent was replaced by the same volume of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States). The absorbance at 540 nm was measured using a FLUOstar Omega spectrophotometer (BMG Labtech, Ortenberg, Germany).

MISSION® Lentiviral Transduction Particles (Cat. SHCLNV, Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States) were used to integrate shRNA into the genome of AGS cells to knockdown TNFR1 and TNFR2 expression. Verified viral vectors were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich, and the standard manu-facturer’s protocol was followed to generate the cell line. Stably transfected clones were selected by growing the cells in the presence of puromycin or G418, which acted as selection pressure (for TNFR1: 1 μg/mL puromycin and for TNFR2: 400 μg/mL G418). Different plasmids containing shRNAs were used to generate clones, of which the one showing the best knockdown efficiency was used for all experiments. The sequence of the shRNA in the construct was CTTGAAGGAACTACTACTAAG for TNFR1 and GCCGGCTCAGAGAATACTATG for TNFR2. TNFR1 and TNFR2 levels were assessed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and Western blotting to verify the knockdown. Similar transfections were carried out with an empty vector (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States), which served as the transfection control.

Protein extraction was performed by lysis of nonsilenced AGS cells and AGS cells containing a shRNA or an empty vector with CelLyticTM MT Cell Lysis Reagent (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States). The lysis reaction was centrifuged at 12000 g for 10 min after a 15 min incubation. The protein concentration was determined using a PierceTM BCA Protein Assay kit (Thermo Scientific, Massachusetts, United States) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Thirty micrograms of protein was separated on an 8%-12% sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel by electrophoresis (120 min) and then transferred to PVDF or nitrocellulose membranes (MilliPore Corporation, Burlington, Massachusetts, EUA) using an Electrotransfer TE70XP system (Hoefer) for 80 min. Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk for 60 min and were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following primary antibodies: Anti-TNFR1 (dilution 1:500) (Cell Signalling, Massachusetts, United States), anti-TNFR2 (dilution 1:5000) (Abcam Cambridge, United Kingdom) and anti-GAPDH (dilution 1:30000) (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom). After being washed, the membranes were incubated at room temperature under stirring with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (dilution 1:2000) secondary antibodies (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom). Bands were revealed by enhanced chemiluminescence, visualized in a ChemiDocTM Imaging System (BioRad, Hercules, California, United States) and quantified using Image Lab 6.0 Software (BioRad, Hercules, California, United States).

After 6 h of incubation, the medium containing H. pylori extract or water was removed, and total RNA was extracted from AGS cells with a miRNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, United States) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Complementary DNA (cDNA) for mRNA and miRNA was synthesized using a High-Capacity cDNA Archive Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States) and a TaqMan® MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States), respectively. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed with TaqMan® assays (Applied Biosystems, California, United States) for the genes TNFA (Hs01113624_g1), TNFR1 (TNFRSF1A) (Hs01042313_m1), TNFR2 (TNFRSF1B) (Hs00961749_m1), TRADD (Hs00182558_m1), TRAF2 (Hs00184192_m1), CFLIP (CFLAR) (Hs00153439_m1), NFKB1 (Hs 00765730_m1), NFKB2 (Hs01028901_g1), CASP8 (Hs01116281_m1) and CASP3 (Hs00234387_m1) and for the target miRNAs hsa-miR-19a-3p (MIMAT0000073; ID 000395), hsa-miR-34a-3p (MIMAT0004557; ID 002316), hsa-miR-103a-3p (MIMAT0000101; ID 000439), hsa-miR-130a-3p (MIMAT0000425; ID 000454) and hsa-miR-181c-5p (MIMAT0000258; ID 000482) (Applied Biosystems, California, United States), as described in our previous study[14]. ACTB (Catalogue#: 4352935E) and GAPDH (Catalogue#: 4352934E) genes were used for normalization of mRNA quantification, while endogenous RNU6B (ID 001093) and RNU48 (ID 001006) levels were used for miRNAs. All reactions were performed in triplicate. Relative quantification (RQ) of mRNA and miRNA expression was calculated by the 2(-∆∆Ct) method[17], and nonsilenced AGS without H. pylori extract treatment was used as a calibrator (AGS-C). RQ values are expressed as the mean ± SD of gene and miRNA expression for all experimental groups in relation to nonsilenced and untreated AGS, with RQ = 1.

The cell distribution at different phases of the cell cycle was estimated by measuring the cellular DNA content using flow cytometry. After incubation with H. pylori extract or water, nonsilenced AGS, shTNFR1 and shTNFR2 cell lines were harvested with trypsin and fixed in 70% ethanol at 4 °C for at least 24 h. Subsequently, the cells were washed, centrifuged and incubated with 200 μL of Guava® Cell Cycle Reagent (Merck Millipore, Burlington, Massachusetts, United States) for 30 min in the dark. Cell cycle distribution was measured by a Guava® EasyCyte Flow Cytometer and analysed with Guava® InCyte software (Merck Millipore, Burlington, Massachusetts, United States).

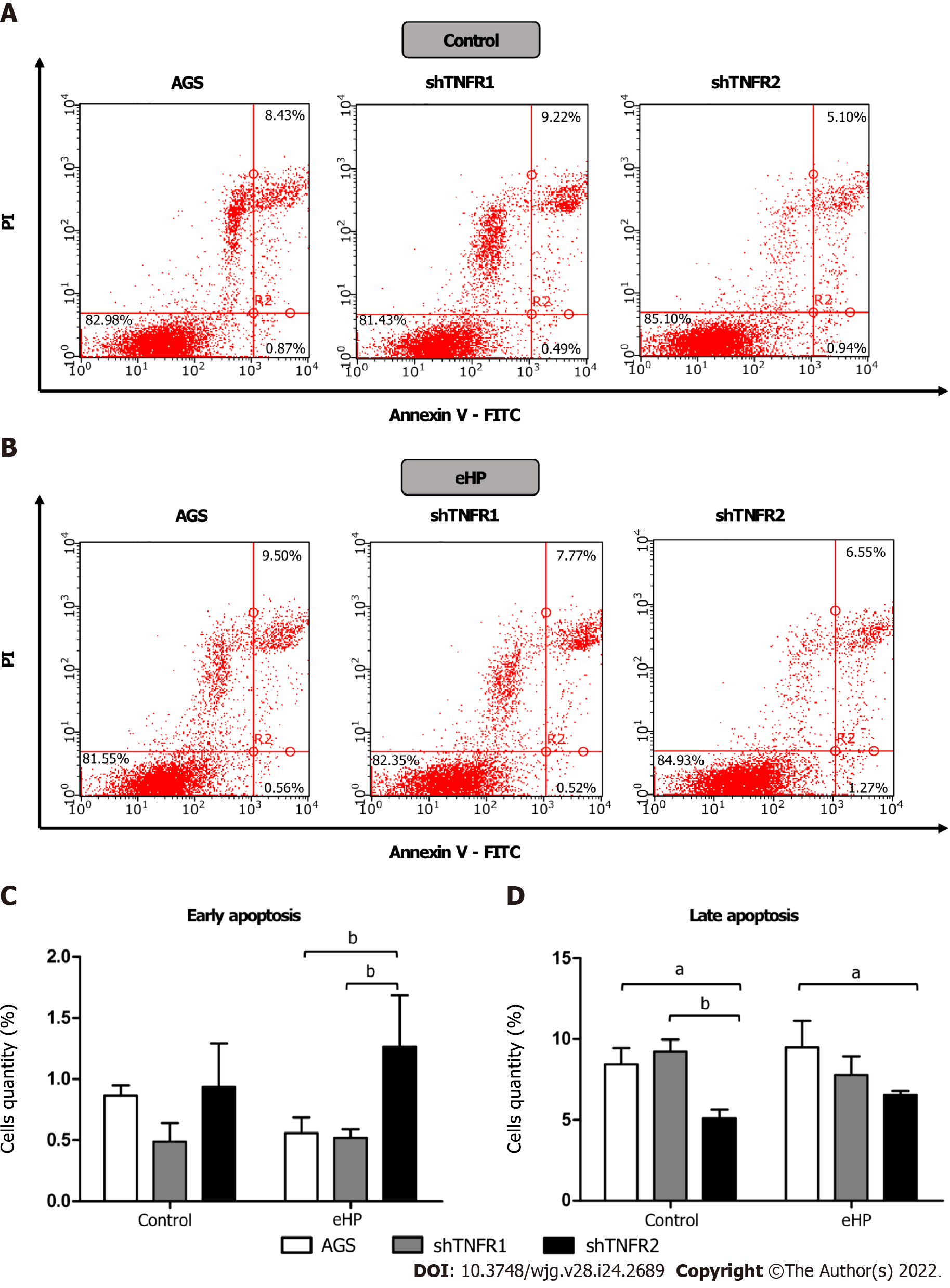

Apoptotic cell death was also measured by flow cytometry using a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit (BD PharmingenTM; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, United States) according to the modified manufacturer’s protocol. After treatment, adherent cells were harvested with Accutase® (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States) since this solution avoids membrane damage[18]. After this step, the cells were washed with cold phosphate-buffered saline, centrifuged, resuspended in 1× binding buffer and stained with 5 μL of Annexin V-FITC and 5 μL of propidium iodide (PI, 50 μg/mL) for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. The labelling of cells was evaluated using a flow cytometer and was analysed with Guava® InCyte software. From the scatter diagram and quadrant plotting, the results are presented as follows: Living cells (FITC-/PI-) located in the lower left quadrant, early apoptotic cells (FITC+/PI-) in the lower right quadrant and late apoptotic cells (FITC+/PI+) in the upper right quadrant.

Statistical analysis of the data was performed in GraphPad Prism Software version 6.01 using two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. The results are expressed as the mean ± SD from three experiments conducted independently. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Initially, both AGS and HGC-27 cell lines were cultured to evaluate the mRNA expression levels of TNFA, TNFR1 and TNFR2 receptors by qPCR. The analyses showed that both cell lines expressed TNFA and TNFR1, but TNFR2 was expressed at lower levels in HGC-27 cells than it was in AGS cells (Supplementary Figure 1). The AGS cell line was chosen for additional experiments since it was not reasonable to use HGC-27 in the TNFR2 silencing experiments.

To standardize treatment conditions, several volumes of H. pylori extract (50, 100, 150 and 200 μL) were tested at different incubation times (4, 6 and 24 h) in the AGS cell line to establish the best conditions for inducing TNFA expression without reducing cell viability. The best results were obtained with an H. pylori extract concentration of 30% v/v (150 μL) at 6 h of incubation (Supplementary Figures 2 and 3). Under these conditions, there was an increase in TNFA expression (RQ = 3.59) without an impact on cell viability (98.9%).

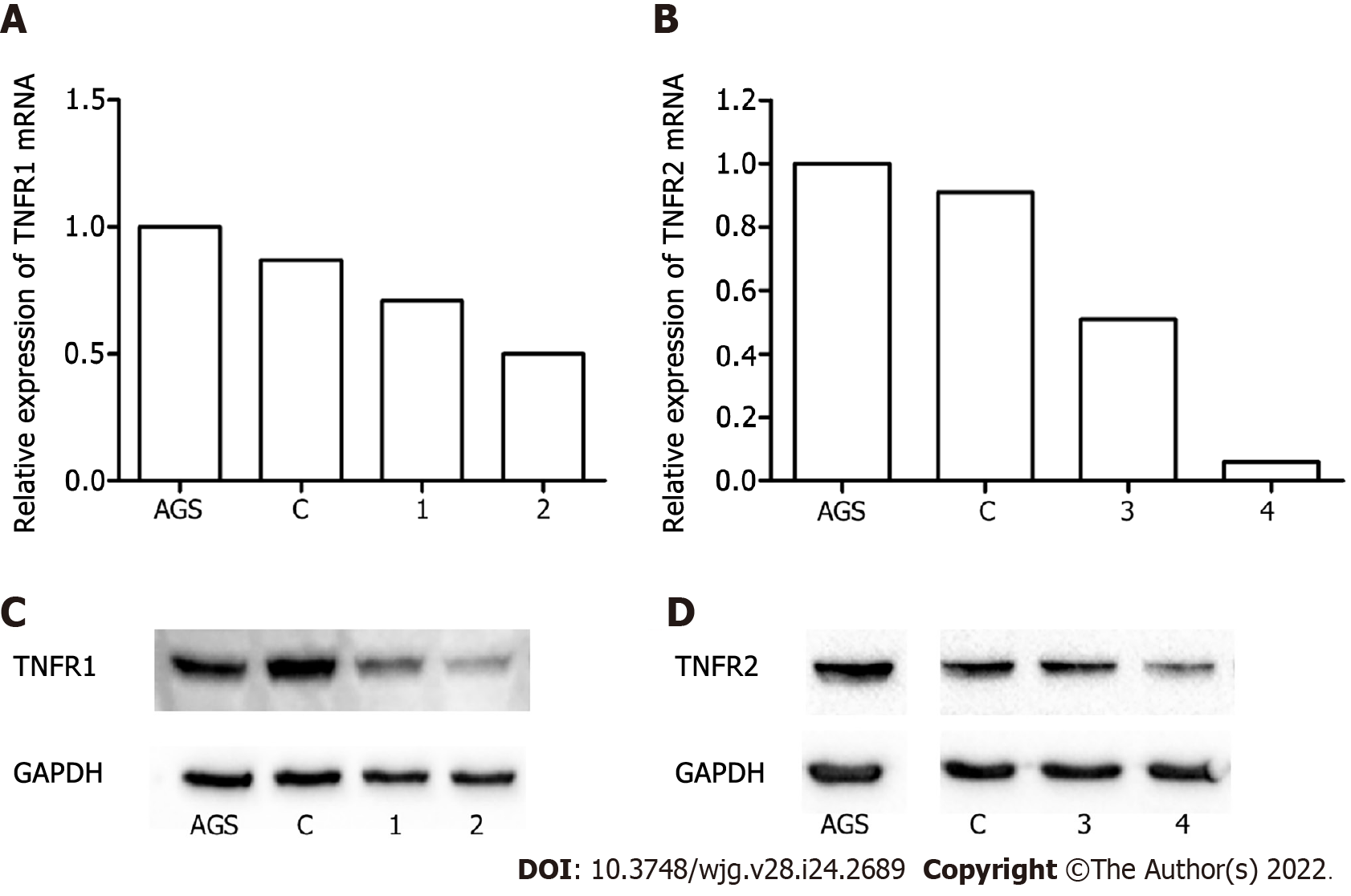

The effect of TNFR1 and TNFR2 downregulation on GC cells was evaluated after transfection of the AGS cell line with two specific shRNAs targeting the genes, TNFR1 (called shTNFR1) and TNFR2 (called shTNFR2), followed by antibiotic selection. RT–qPCR and Western blotting were used to evaluate the efficiency of silencing. Stable lines with the shRNAs exhibited a 59% reduction in TNFR1 and a 63% reduction in TNFR2 protein expression (Figure 1).

Initially, we evaluated the effect of treatment with H. pylori extract on the expression of genes of the TNF-α signalling pathway in nonsilenced AGS cells. After H. pylori extract treatment (AGS-H. pylori extract), nonsilenced AGS cells showed significantly upregulated mRNA expression of TNFR1 and of anti-apoptotic and cell proliferation genes, such as CFLIP, NFKB1 and NFKB2 (Supplementa-ry Figure 4A), compared to the control (AGS-C). In addition, H. pylori extract treatment increased the mRNA expression of NFKB1 and NFKB2 in a TNFR1-downregulated cell line (shTNFR1-H. pylori extract), whereas the expression of TNFR2 and TRADD was reduced (Supplementary Figure 4B). On the other hand, the expression of the evaluated genes was not significantly changed by H. pylori extract treatment in the shTNFR2 cell line (Supplementary Figure 4C).

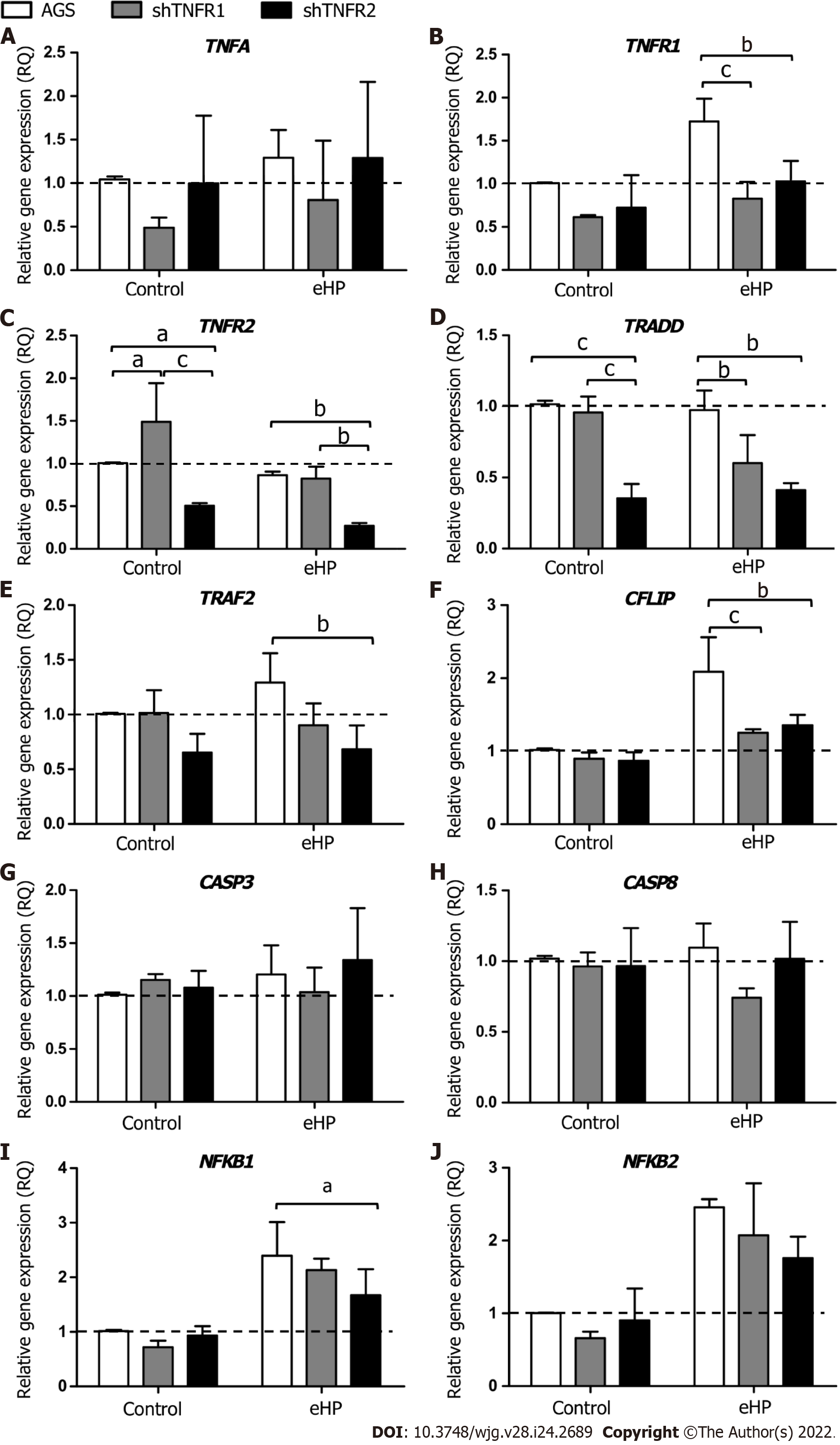

With regard to the influence of TNFR1 and TNFR2 downregulation on the expression of TNF-α signalling genes (Figure 2), a significantly downregulated mRNA expression of TNFR1 (RQ = 0.83 and 1.03, respectively), TRADD (RQ = 0.60 and 0.41, respectively) and CFLIP (RQ = 1.25 and 1.36, respectively) was observed in shTNFR1-H. pylori extract and shTNFR2-H. pylori extract cells compared to that in AGS-H. pylori extract cells (RQ = 1.73, 0.98 and 2.09, respectively) (Figure 2B, D and F). Furthermore, TNFR2 (RQ = 0.27, P < 0.05), TRAF2 (RQ = 0.68, P < 0.05) and NFKB1 (RQ = 1.67, P < 0.05) were reduced in shTNFR2-H. pylori extract cells compared to AGS-H. pylori extract cells (RQ = 0.86, 1.29 and 2.39, respectively) (Figure 2C, E and I). When we compared the nonsilenced and silenced AGS cell lines without H. pylori extract treatment (control-C), TNFR2 mRNA expression was increased in shTNFR1-C (RQ = 1.49) compared to AGS-C (RQ = 1.00) and reduced in shTNFR2-C (RQ = 0.50) compared to shTNFR1-C and AGS-C. Likewise, TRADD mRNA expression was downregulated in shTNFR2-C (RQ = 0.35) compared to the other control groups (AGS-C and shTNFR1-C). There was no significant change in TNFA, CASP3, CASP8 and NFKB2 mRNA expression.

In general, the downregulation of TNFR1 and TNFR2 significantly influenced the mRNA expression of TRADD (P < 0.001) and TRAF2 (P < 0.01), whereas the expression of TNFR1, TNFR2 and CFLIP was also affected by treatment with H. pylori extract (P < 0.01 for all). In contrast, only the H. pylori extract treatment contributed to the differences observed in NFKB1 and NFKB2 mRNA expression (P < 0.001 for both).

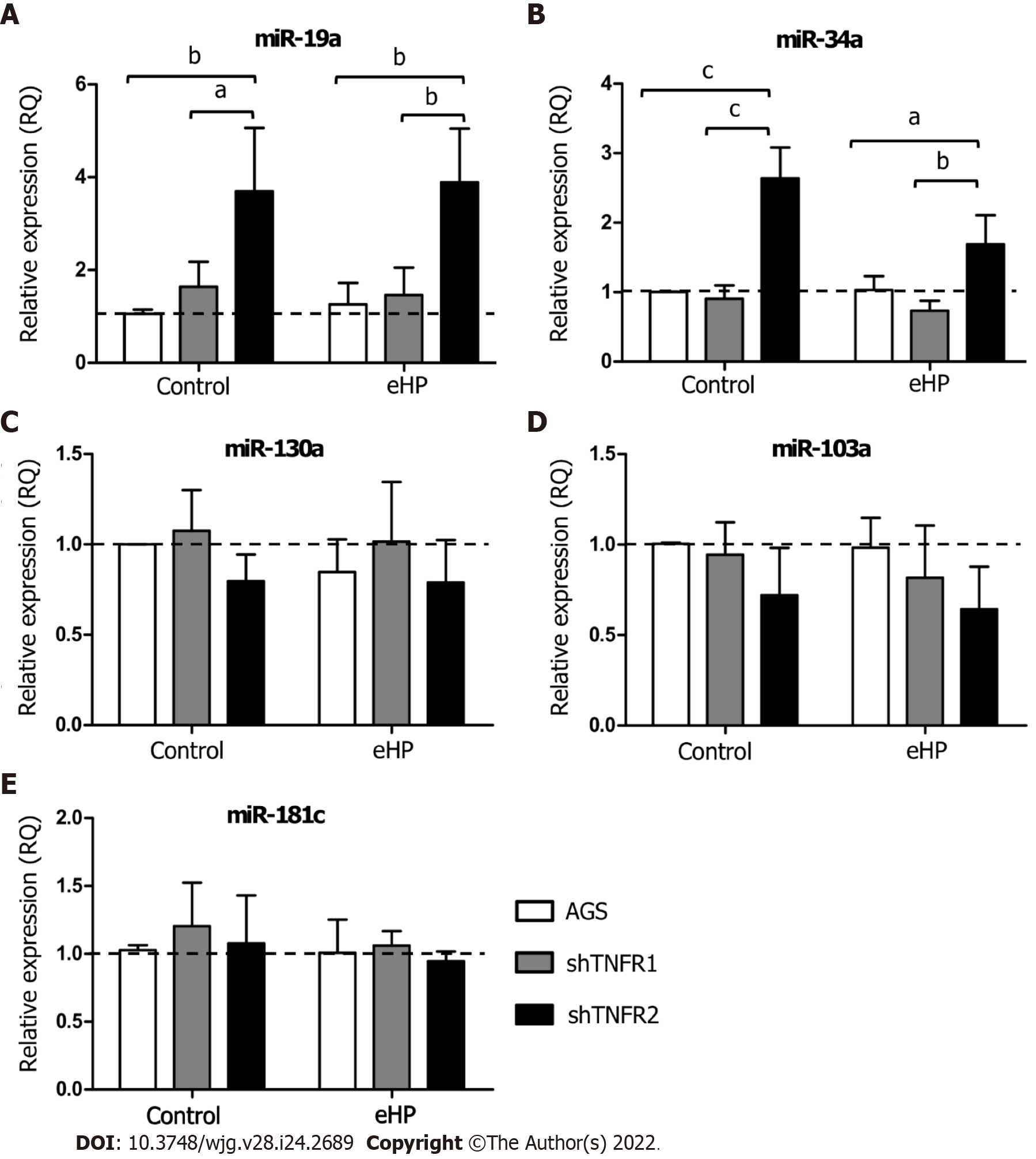

The expression of miRNAs miR-19a, miR-34a, miR-103a, miR-130a and miR-181c was evaluated in the AGS, shTNFR1 and shTNFR2 cell lines with and without H. pylori extract treatment (Figure 3 and Supplementary Figure 5). No significant change in the expression of these miRNAs was found in AGS and shTNFR1 cells regardless of H. pylori extract treatment. However, TNFR2 receptor downregulation resulted in a significant increase in the expression of miR-19a and miR-34a in shTNFR2-C cells (RQ = 3.70 and 2.64, respectively) compared with that of the AGS-C (P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively) and shTNFR1-C cells (P < 0.05 and P < 0.001, respectively) cells and in shTNFR2-H. pylori extract cells (RQ = 3.89 and 1.69, respectively) compared to AGS-H. pylori extract (P < 0.01 and P < 0.05, respectively) and shTNFR1-H. pylori extract cells (P < 0.01 and P < 0.01, respectively) (Figure 3A and B).

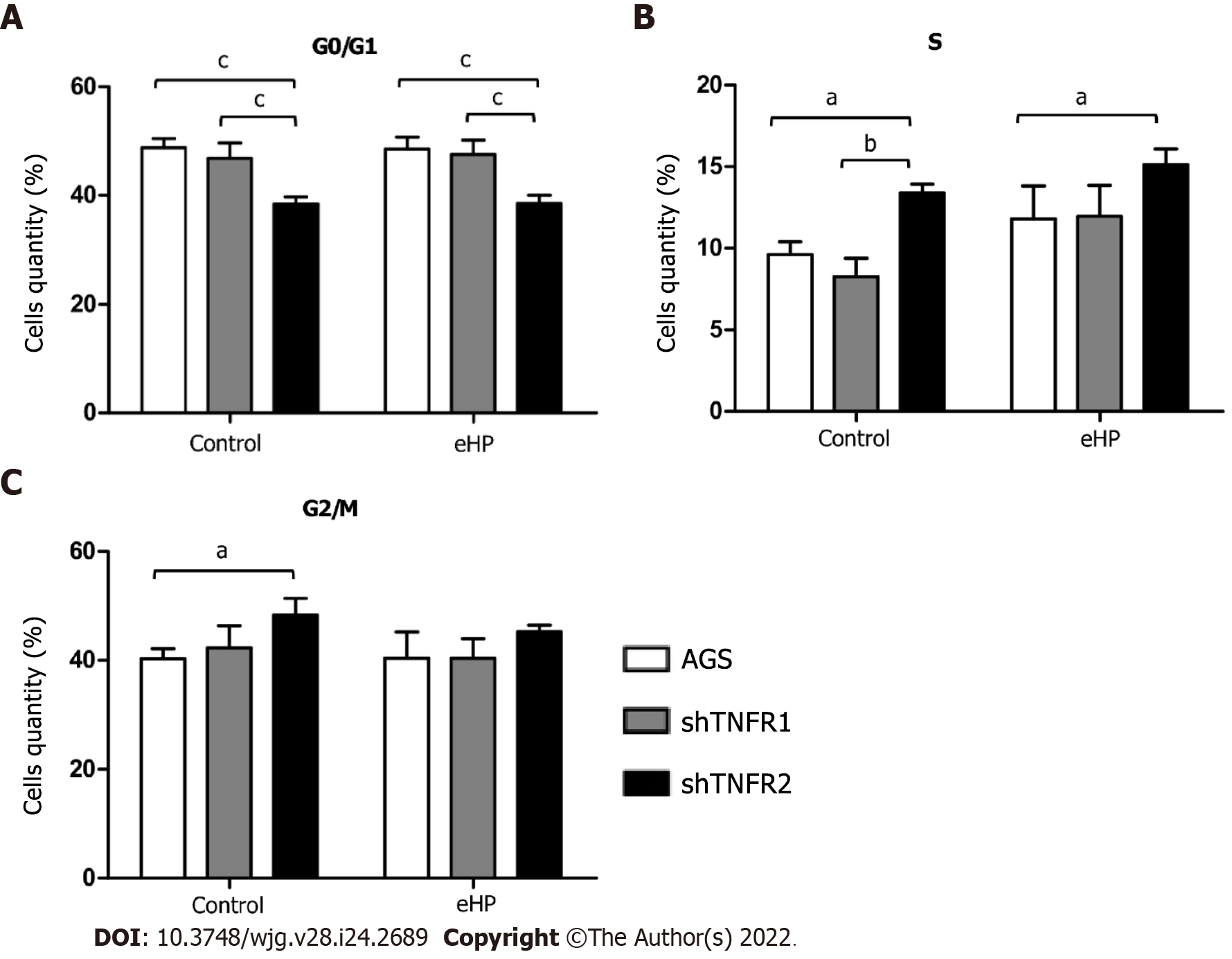

The effect of TNFR1 and TNFR2 downregulation after H. pylori extract treatment on cell cycle progression was evaluated by flow cytometry. Overall, H. pylori extract treatment did not affect the cellular distribution in the G0/G1, S and G2/M phases in nonsilenced AGS, shTNFR1 and shTNFR2 cells (Supplementary Figure 6). However, TNFR2 downregulation significantly reduced the number of cells in G0/G1 phase regardless of H. pylori extract treatment and led to an increase in the number of cells in S and G2/M phases in shTNFR2-C cells compared to that of the AGS-C cells (Figure 4).

In addition, we also investigated the effect of partial TNFR1 and TNFR2 inhibition and H. pylori extract treatment on apoptosis, which was evaluated through Annexin-V and PI double staining by flow cytometry. Treatment with H. pylori extract did not induce changes in the rates of early and late apoptosis in the nonsilenced AGS and both silenced AGS cell lines compared to the respective untreated cell lines (Supplementary Figure 7). However, after H. pylori extract treatment, the percentage of early apoptotic cells was significantly higher in shTNFR2 cells (1.27%) than in AGS (0.56%) and shTNFR1 cells (0.52%), whereas the percentage of late apoptotic cells was significantly reduced after H. pylori extract treatment (Figure 5). Together with the cell cycle results, these data indicate a relationship between decreased cell quantity in the G0/G1 phase and increased early apoptosis as a result of TNFR2 downregulation.

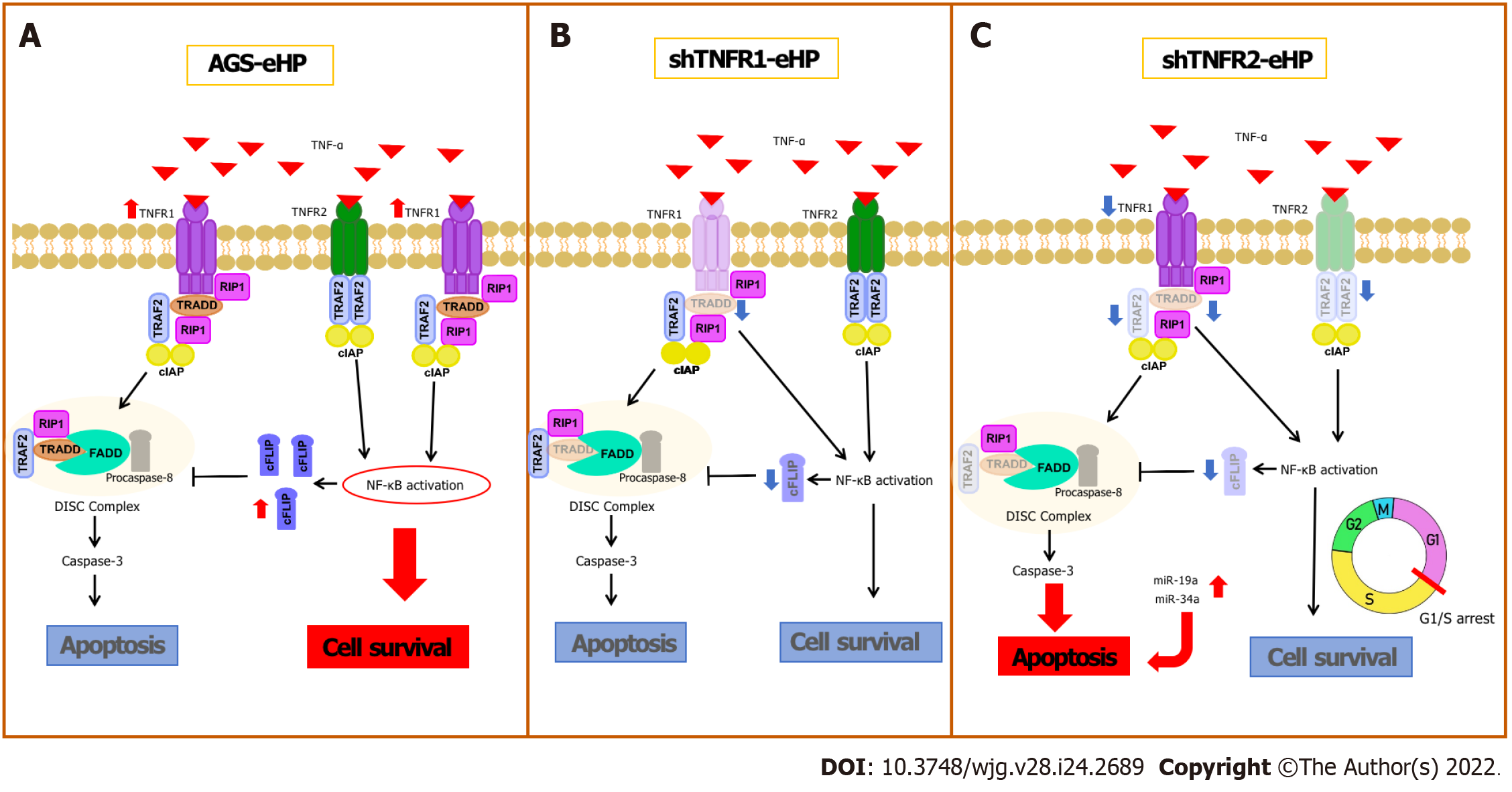

TNFR1 and TNFR2 differ in their intracellular domains and cellular expression; thus, the role of each receptor in the TNF-α-triggered signalling pathway varies according to the pathological condition, activating different cellular processes, such as cell survival and apoptosis[10]. This is the first study to investigate the effect of TNFR1 and TNFR2 downregulation on AGS cells treated with H. pylori extract. Our results show that H. pylori extract treatment of nonsilenced AGS cells upregulated the mRNA expression of proliferation (NFKB1 and NFKB2) and antiapoptotic genes (CFLIP) by activating TNFR1. TNFR1 downregulation did not promote extensive changes in the expression of genes or miRNAs involved in the TNF-α signalling pathway or in cellular processes. In contrast, TNFR2 downregulation significantly decreased TRADD and TRAF2 mRNA expression, which may impair TNFR1-mediated TNF-α signalling, and increased miRNA expression, which promoted a block in the G1/S transition and an increase in early apoptosis.

H. pylori infection can deregulate the expression of several genes and miRNAs, as previously shown by our research group[6]. Recently, increased mRNA levels of TNFA and other proinflammatory mediators, such as interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-8, have been reported in an AGS cell line after infection by H. pylori[19]. Our results show high TNFR1 mRNA expression after H. pylori extract treatment in nonsilenced AGS cells, suggesting that H. pylori infection promotes activation of the TNFR1-mediated TNF-α signalling pathway in AGS cells, directing signal transduction to the cell survival pathway due to the increased expression of NFKB1, NFKB2 and CFLIP (Figure 6A). In agreement with this finding, previous studies showed that H. pylori activates NF-κB in a manner dependent on the bacterial cell number[20] due to significant IκB-α degradation[21], resulting in the induction of anti-apoptotic gene transcription, such as CFLIP transcription[22]. Therefore, our results indicate that H. pylori extract also induces cell survival and inflammation due to TNFR1-mediated TNF-α signalling, which leads to NF-κB activation and the consequent production of antiapoptotic mediators, such as cFLIP.

TNFR1 downregulation resulted in a significant increase in TNFR2 mRNA expression in nontreated AGS cells, while a decrease in the expression of TRADD and CFLIP mRNA was observed in cells treated with H. pylori extract, although no change was observed in apoptosis and cell cycle assays (Figure 6B). In oesophageal carcinoma cells treated with TNFR1-siRNA, Changhui et al[23] demonstrated an increase in cell proliferation and a reduction in apoptosis rate after 24 h of transfection, and the cell proliferation level was time-dependent[19]. The present study, when evaluated together with the results of H. pylori extract, suggests that the assays of cellular processes after 6 h of treatment may have been insufficient in shTNFR1 and nonsilenced AGS cells. Wan et al[24] showed that AGS cell coculture with H. pylori inhibited apoptosis and increased viability through upregulation of TRAF1, which was triggered by NF-κB activation. However, the peak of TRAF1 expression occurred after 12 h of infection, and its effect on cell viability started only after 24 h. Therefore, the role of TNFR1 downregulation in GC cell lines still needs to be further investigated.

Conversely, the downregulation of TNFR2 expression significantly decreased the expression of two important mediators of the TNFR1-mediated signalling pathway, TRAF2 and TRADD, in addition to NFKB1, CFLIP and TNFR1 expression. Moreover, there was an increase in early apoptosis, with concomitant G1/S transition phase arrest (Figure 6C). These results agree with those previously reported by our group in GC patient samples, in which we found upregulation of TNF/TNFR2 and cellular survival genes such as TRAF2, CFLIP, and NFKB2 and downregulation of TNFR1 and CASP3[14], thus emphasizing the important role of TNFR2 in gastric carcinogenesis and TNFR2 silencing as a promising strategy for anticancer therapy[25].

TRADD is an essential adaptor protein that functions in TNFR1-mediated apoptotic signalling under physiological conditions[26]. However, the dependence of this mediator seems to be cell-type specific[27], as TRADD knockout mice were resistant to TNFR1-induced toxicity in a hepatitis model[28]. However, this pathway was not completely impaired in macrophages deprived of TRADD[27]. Therefore, apoptosis can occur even with reduced expression of TRADD, as observed in the present study after TNFR2 downregulation. In turn, TRADD inhibition reduces NF-κB activation[12], impairing the transcription of anti-apoptotic genes, such as TRAF2 and CFLIP, as observed in this study.

As mentioned, shTNFR2 cells also exhibited reduced expression of TRAF2. This protein has an essential role in signal transduction and is triggered by both TNFR1 and TNFR2, suggesting the existence of crosstalk between them[29], which influences the signalling outcome after TNF binding[30]. TRAF2 recruits cIAP1 and cIAP2 after interaction with these receptors, thereby triggering nuclear translocation of NF-κB[30]. Therefore, TRAF2 is a negative regulator of TNF-induced apoptosis[30], and the use of this protein after TNFR2 activation results in TNFR1-induced apoptosis to the detriment of proliferation[25]. Therefore, a decrease in TRAF2 expression favours TNFR1-mediated apoptosis, contributing to the increase in the percentage of early apoptotic cells after TNFR2 downregulation.

Moreover, we found that TNFR2 downregulation also promoted a decrease in the ratio of cells in the G0/G1 phase and an increase the ratio of cells in the S and G2/M phases, suggesting that TNFR2 inhibition may delay cell cycle progression and arrest cells at the G1/S transition[31]. These changes in the cell cycle could also be related to the DNA damage response[32], leading cells to early apoptosis, as seen in our results. Recent studies have shown increased expression of genes related to the response to DNA damage and repair, such as APE1, H2AX and PARP-1, in GC samples, thus possibly influencing the survival of tumour cells[33,34]. Yang et al[35] demonstrated that TNFR2 enhances DNA damage repair by regulating PARP expression in breast cancer cells. Furthermore, they showed that TNFR2 silencing led to an increase in pH2AX, which is a DNA damage marker.

Based on the function of each receptor and the existence of crosstalk between them, it is possible that the simultaneous inhibition of both TNFR1 and TNFR2 may have a greater antitumor effect on GC than the downregulation of TNFR2 alone. Furthermore, TNF-α and its receptors, in addition to being expressed by tumour cells, are also expressed by cells present in the tumour microenvironment as immune cells[36]. Oshima et al[8] demonstrated that the stimulation of TNFR1-mediated TNF-α signalling in cells in the tumour microenvironment promoted gastric tumorigenesis through the induction of tumour-promoting factors (Noxo1 and Gna14) in tumour epithelial cells, highlighting the importance of the tumour microenvironment[37] and the need for in vivo studies.

Furthermore, considering the important role of miRNAs in the development of cancer, as they act as regulators of signalling pathways and are consequently involved in various cellular processes, we also evaluated the expression of miRNAs miR-19a, miR-34a, miR-103a, miR-130a and miR-181c. These miRNAs were chosen from data analysis publishedin public databases[38-42] and due to their interaction with TNF-α pathway genes, as observed in our recent study[14]. Regardless of H. pylori extract treatment, shTNFR1 and nonsilenced AGS cells did not dysregulate miRNA expression. However, TNFR2 downregulation caused an upregulation of miR-19a and miR-34a (Figure 3A and B).

MiR-34a is dysregulated in different types of cancer and is linked to the proliferation, differentiation, migration, invasion, treatment, and prognosis of cancer[43]. Although most studies suggest a tumour-suppressor role for miR-34a[44-46], we recently observed overexpression of this miRNA in GC samples[14], thus also indicating its oncogenic action. In contrast, in both AGS and BGC-823 cell lines, an upregulation of this miRNA inhibited proliferative and migratory abilities in sevoflurane-induced GC cells, whereas in vivo knockdown of miR-34a stimulated tumour growth, indicating its action as a tumour suppressor in the AGS cell line[47]. In addition, stable transfection of pre-mir-34a in KatoII cells increased the percentage of apoptotic cells and reduced the proliferation rate, suggesting that its high expression promotes apoptosis[48]. In the present study, upregulation of this miRNA in shTNFR2 cells suggests that miR-34a expression can be modulated by TNFR2-mediated TNF-α signalling and is able to exert an anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effect. Similarly, miR-19a was overexpressed in the shTNFR2 cell line, indicating that miR-19a and TNFR2 are related to each other in GC. miR-19a has a known oncogenic function in various kinds of cancer[49], with TNFA, TNFR1 and TNFR2 being its validated targets[38,39,50]. However, miR19a may play a tumour-suppressive role, as reported in prostate cancer, by suppressing invasion and migration in bone metastasis[51], and in rectal cancer cells, by inducing apoptosis[52]. For both miRNAs, functional studies are needed to assess what targets the miRNAs are related to with respect to TNF-α signalling in GC.

The other miRNAs evaluated (miR-103a, miR-130a and miR-181c) were not dysregulated in the AGS cell line. Although different studies have shown the involvement of these miRNAs in gastric neoplasms[53-55], their pro- or antitumor roles are still controversial. This is due to the influence of several factors in the regulation of gene expression, such as the stage of tumour development and the presence or absence of infectious agents[6].

In conclusion, based on our results, shRNA-mediated downregulation of TNFR2 in AGS cells was able to reduce the expression of pro-survival and anti-apoptotic genes, in addition to affecting miRNA expression, the cell cycle, and promoter apoptosis. The blocking of TNFR2 expression may cause antitumor effects, suggesting possible targets for future studies into therapeutic strategies for treating GC. Furthermore, the H. pylori extract increased the expression of prosurvival genes, mainly through TNFR1-mediated TNF-α signalling, thus emphasizing the role of bacterial infection in promoting GC progression.

The tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) signalling pathway triggered by TNFR1 and TNFR2 controls several biological processes, influencing cell fate. Thus, the deregulation of this pathway to cause an imbalance between the processes of cell survival and death may contribute to the tumorigenic process. This variety of functions is exercised by the ability of TNF-α to bind to TNFR1 or TNFR2, which results in different cellular processes. Both receptors are transmembrane proteins and are largely similar in extracellular structure, but their intracellular domains are different, and dictate the cellular fate for either survival or death. Since only TNFR1 has a death domain, the TNF-α signalling pathway triggered by TNFR1 is able to induce both cell survival and apoptosis, whereas TNFR2 results only in cell survival. The TNF-α signalling pathway also modulates the immune response and inflammation, so deregulation of this pathway has been implicated in inflammatory diseases and cancer. Therefore, studies are needed to better understand the relationships of this signalling network via TNFR1 and TNFR2 and its protumorigenic or antitumorigenic effects.

We proposed the present study based on our previous studies, which showed deregulation in the expression of genes and miRNAs of the TNF-α signalling pathway and its receptors TNFR1 and TNFR2 in fresh tissues of chronic gastritis and gastric cancer (GC) patients. Therefore, we decided to evaluate the effect of silencing TNFR1 and TNFR2 on GC cell lines.

According to the role of TNFR1 and TNFR2 in cellular responses triggered by TNF-α, and considering that studies addressing the role of these receptors in gastric neoplasm are limited and inconclusive, we proposed to couple the silencing of TNFR1 and TNFR2 receptors in an AGS gastric cell line and the treatment with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) extract to determine the effects on TNF-α mRNA expression and on downstream genes related to its signalling pathway. Moreover, we also investigated previously studied miRNAs that target genes in the TNF-α pathway to jointly determine their influence on the cell cycle and apoptosis.

Stable AGS GC cells containing TNFR1 and TNFR2 receptors downregulated by specific shRNAs and nonsilenced cell lines were treated with 30% v/v H. pylori extract [H. pylori Tox+ strain (cagA+/vacA s1m1)] for 6 h. After silencing, TNFR1 and TNFR2 levels were assessed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and Western blotting to confirm the knockdown effect. Subsequently, mRNA and miRNAs were quantified by qPCR using TaqMan gene and miRNA expression assays. The MTT assay was employed to evaluate the viability of silenced and nonsilenced AGS cells after different treatment conditions with H. pylori extract, and flow cytometry was used for cell cycle analysis and apoptosis.

Our results showed that H. pylori extract treatment increased the expression of genes involved in cell survival (NFKB1 and NFKB2) and inhibited apoptosis (CFLIP) and TNFR1 in nonsilenced AGS cells. TNFR1 downregulation significantly decreased the expression of the TRADD and CFLIP genes; however, no change in the cell cycle, apoptosis or miRNA levels was observed. In turn, TNFR2 downregulation decreased the expression of the TRADD and TRAF2 genes, which are both important downstream mediators of the TNFR1-mediated pathway, as well as the NFKB1 and CFLIP genes, while upregulating the expression of miR-19a and miR-34a. Consequently, there was a decrease in the ratio of cells in the G0/G1 phase and an increase in cells in the S phase, as well as the promotion of early apoptosis.

Our findings highlight that treatment with H. pylori extract increased the expression of pro-survival genes, mainly through TNFR1-mediated TNF-α signalling, emphasizing the role of bacterial infection in promoting GC progression. In the AGS cell line, TNFR1 and TNFR2 downregulation decreased the expression of prosurvival and antiapoptotic genes and affected miRNA expression and cellular processes, such as the cell cycle and apoptosis, emphasizing that shRNA-mediated downregulation of these receptors can have an antitumor effect.

According to our results, we can mainly highlight the important role of TNFR2 in the TNF-α pathway in GC, indicating that silencing TNFR2 can reduce the expression of survival and anti-apoptotic genes. Thus, blocking this receptor may result in antitumor effects, suggesting possible targets for future in vivo studies into therapeutic strategies for treating GC.

We thank Dr Sonia Maria Oliani, Department of Biological Sciences, UNESP, for making the flow cytometer available, Janesly Prates for training on the flow cytometer, Dr Fernando Ferrari, Department of Computer Science and Statistics, UNESP, for the statistical support, André Brandão do Amaral for contribution to Figure 6, and Marilanda Ferreira Bellini for recording the audio core tip.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A, A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Keikha M, Iran; Tilahun M, Ethiopia S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Chen YX

| 1. | International Agency for Research on Cancer. Cancer Today fact Sheets, 2018. [cited 11 January 2022]. Available from http://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/7-Stomach-fact-sheet.pdf. |

| 2. | Ministério da Saúde, Instituto Nacional de Câncer José Alencar Gomes da Silva. Estimativa 2020-Incidência de câncer no Brasil. 2019. [cited 11 January 2022]. Available from: https://www.inca.gov.br/sites/ufu.sti.inca.local/files//media/document//estimativa-2020-incidencia-de-cancer-no-brasil.pdf. |

| 3. | Yousefi B, Mohammadlou M, Abdollahi M, Salek Farrokhi A, Karbalaei M, Keikha M, Kokhaei P, Valizadeh S, Rezaiemanesh A, Arabkari V, Eslami M. Epigenetic changes in gastric cancer induction by Helicobacter pylori. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:21770-21784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cadamuro AC, Rossi AF, Maniezzo NM, Silva AE. Helicobacter pylori infection: host immune response, implications on gene expression and microRNAs. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:1424-1437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 5. | Chen R, Yang M, Huang W, Wang B. Cascades between miRNAs, lncRNAs and the NF-κB signaling pathway in gastric cancer (Review). Exp Ther Med. 2021;22:769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rossi AF, Cadamuro AC, Biselli-Périco JM, Leite KR, Severino FE, Reis PP, Cordeiro JA, Silva AE. Interaction between inflammatory mediators and miRNAs in Helicobacter pylori infection. Cell Microbiol. 2016;18:1444-1458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mahdavi Sharif P, Jabbari P, Razi S, Keshavarz-Fathi M, Rezaei N. Importance of TNF-alpha and its alterations in the development of cancers. Cytokine. 2020;130:155066. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Oshima H, Ishikawa T, Yoshida GJ, Naoi K, Maeda Y, Naka K, Ju X, Yamada Y, Minamoto T, Mukaida N, Saya H, Oshima M. TNF-α/TNFR1 signaling promotes gastric tumorigenesis through induction of Noxo1 and Gna14 in tumor cells. Oncogene. 2014;33:3820-3829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yang S, Wang J, Brand DD, Zheng SG. Role of TNF-TNF Receptor 2 Signal in Regulatory T Cells and Its Therapeutic Implications. Front Immunol. 2018;9:784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 271] [Article Influence: 38.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gough P, Myles IA. Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptors: Pleiotropic Signaling Complexes and Their Differential Effects. Front Immunol. 2020;11:585880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 34.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Josephs SF, Ichim TE, Prince SM, Kesari S, Marincola FM, Escobedo AR, Jafri A. Unleashing endogenous TNF-alpha as a cancer immunotherapeutic. J Transl Med. 2018;16:242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 26.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Li Z, Yuan W, Lin Z. Functional roles in cell signaling of adaptor protein TRADD from a structural perspective. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2020;18:2867-2876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Brenner D, Blaser H, Mak TW. Regulation of tumour necrosis factor signalling: live or let die. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:362-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 559] [Cited by in RCA: 727] [Article Influence: 72.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rossi AFT, Contiero JC, Manoel-Caetano FDS, Severino FE, Silva AE. Up-regulation of tumor necrosis factor-α pathway survival genes and of the receptor TNFR2 in gastric cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2019;11:281-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Santos JC, Gambeloni RZ, Roque AT, Oeck S, Ribeiro ML. Epigenetic Mechanisms of ATM Activation after Helicobacter pylori Infection. Am J Pathol. 2018;188:329-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Li HQ, Xu C, Li HS, Xiao ZP, Shi L, Zhu HL. Metronidazole-flavonoid derivatives as anti-Helicobacter pylori agents with potent inhibitory activity against HPE-induced interleukin-8 production by AGS cells. ChemMedChem. 2007;2:1361-1369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149116] [Cited by in RCA: 133837] [Article Influence: 5576.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Riedl S, Rinner B, Asslaber M, Schaider H, Walzer S, Novak A, Lohner K, Zweytick D. In search of a novel target - phosphatidylserine exposed by non-apoptotic tumor cells and metastases of malignancies with poor treatment efficacy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1808:2638-2645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 256] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yeon MJ, Lee MH, Kim DH, Yang JY, Woo HJ, Kwon HJ, Moon C, Kim SH, Kim JB. Anti-inflammatory effects of Kaempferol on Helicobacter pylori-induced inflammation. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2019;83:166-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Maeda S, Yoshida H, Ogura K, Mitsuno Y, Hirata Y, Yamaji Y, Akanuma M, Shiratori Y, Omata M. H. pylori activates NF-kappaB through a signaling pathway involving IkappaB kinases, NF-kappaB-inducing kinase, TRAF2, and TRAF6 in gastric cancer cells. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:97-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ham B, Fernandez MC, D'Costa Z, Brodt P. The diverse roles of the TNF axis in cancer progression and metastasis. Trends Cancer Res. 2016;11:1-27. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Micheau O, Lens S, Gaide O, Alevizopoulos K, Tschopp J. NF-kappaB signals induce the expression of c-FLIP. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:5299-5305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 645] [Cited by in RCA: 658] [Article Influence: 27.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Changhui M, Tianzhong M, Zhongjing S, Ling C, Ning W, Ningxia Z, Xiancai C, Haibin C. Silencing of tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 by siRNA in EC109 cells affects cell proliferation and apoptosis. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2009;2009:760540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wan XK, Yuan SL, Wang YC, Tao HX, Jiang W, Guan ZY, Cao C, Liu CJ. Helicobacter pylori inhibits the cleavage of TRAF1 via a CagA-dependent mechanism. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:10566-10574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Moatti A, Cohen JL. The TNF-α/TNFR2 Pathway: Targeting a Brake to Release the Anti-tumor Immune Response. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:725473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Pobezinskaya YL, Liu Z. The role of TRADD in death receptor signaling. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:871-876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Pobezinskaya YL, Kim YS, Choksi S, Morgan MJ, Li T, Liu C, Liu Z. The function of TRADD in signaling through tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 and TRIF-dependent Toll-like receptors. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1047-1054. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ermolaeva MA, Michallet MC, Papadopoulou N, Utermöhlen O, Kranidioti K, Kollias G, Tschopp J, Pasparakis M. Function of TRADD in tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 signaling and in TRIF-dependent inflammatory responses. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1037-1046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Naudé PJ, den Boer JA, Luiten PG, Eisel UL. Tumor necrosis factor receptor cross-talk. FEBS J. 2011;278:888-898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Borghi A, Verstrepen L, Beyaert R. TRAF2 multitasking in TNF receptor-induced signaling to NF-κB, MAP kinases and cell death. Biochem Pharmacol. 2016;116:1-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Qiao F, Gong P, Song Y, Shen X, Su X, Li Y, Wu H, Zhao Z, Fan H. Downregulated PITX1 Modulated by MiR-19a-3p Promotes Cell Malignancy and Predicts a Poor Prognosis of Gastric Cancer by Affecting Transcriptionally Activated PDCD5. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;46:2215-2231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | DiPaola RS. To arrest or not to G(2)-M Cell-cycle arrest : commentary re: A. K. Tyagi et al, Silibinin strongly synergizes human prostate carcinoma DU145 cells to doxorubicin-induced growth inhibition, G(2)-M arrest, and apoptosis. Clin. cancer res., 8: 3512-3519, 2002. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:3311-3314. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Afzal H, Yousaf S, Rahman F, Ahmed MW, Akram Z, Akhtar Kayani M, Mahjabeen I. PARP1: A potential biomarker for gastric cancer. Pathol Res Pract. 2019;215:152472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Manoel-Caetano FS, Rossi AFT, Calvet de Morais G, Severino FE, Silva AE. Upregulation of the APE1 and H2AX genes and miRNAs involved in DNA damage response and repair in gastric cancer. Genes Dis. 2019;6:176-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Yang F, Zhao N, Wu N. TNFR2 promotes Adriamycin resistance in breast cancer cells by repairing DNA damage. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16:2962-2968. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Wu Y, Zhou BP. TNF-alpha/NF-kappaB/Snail pathway in cancer cell migration and invasion. Br J Cancer. 2010;102:639-644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 455] [Cited by in RCA: 604] [Article Influence: 40.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Bubnovskaya L, Osinsky D. Tumor microenvironment and metabolic factors: contribution to gastric cancer. Exp Oncol. 2020;42:2-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Vlachos IS, Paraskevopoulou MD, Karagkouni D, Georgakilas G, Vergoulis T, Kanellos I, Anastasopoulos IL, Maniou S, Karathanou K, Kalfakakou D, Fevgas A, Dalamagas T, Hatzigeorgiou AG. DIANA-TarBase v7.0: indexing more than half a million experimentally supported miRNA:mRNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D153-D159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 541] [Cited by in RCA: 614] [Article Influence: 55.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Dweep H, Gretz N. miRWalk2.0: a comprehensive atlas of microRNA-target interactions. Nat Methods. 2015;12:697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 905] [Cited by in RCA: 1024] [Article Influence: 102.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Liu W, Wang X. Prediction of functional microRNA targets by integrative modeling of microRNA binding and target expression data. Genome Biol. 2019;20:18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 444] [Cited by in RCA: 564] [Article Influence: 94.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Agarwal V, Bell GW, Nam JW, Bartel DP. Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs. Elife. 2015;4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4013] [Cited by in RCA: 5411] [Article Influence: 541.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Miranda KC, Huynh T, Tay Y, Ang YS, Tam WL, Thomson AM, Lim B, Rigoutsos I. A pattern-based method for the identification of MicroRNA binding sites and their corresponding heteroduplexes. Cell. 2006;126:1203-1217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1440] [Cited by in RCA: 1547] [Article Influence: 81.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Kong J, Wang W. A Systemic Review on the Regulatory Roles of miR-34a in Gastrointestinal Cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2020;13:2855-2872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Deng X, Zheng H, Li D, Xue Y, Wang Q, Yan S, Zhu Y, Deng M. MicroRNA-34a regulates proliferation and apoptosis of gastric cancer cells by targeting silent information regulator 1. Exp Ther Med. 2018;15:3705-3714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Yu Y, Wei SG, Weiss RM, Felder RB. TNF-α receptor 1 knockdown in the subfornical organ ameliorates sympathetic excitation and cardiac hemodynamics in heart failure rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2017;313:H744-H756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Wang B, Li D, Kovalchuk I, Apel IJ, Chinnaiyan AM, Wóycicki RK, Cantor CR, Kovalchuk O. miR-34a directly targets tRNAiMet precursors and affects cellular proliferation, cell cycle, and apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:7392-7397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Chen H, Zhu XM, Luo ZL, Hu YJ, Cai XC, Gu QH. Sevoflurane induction alleviates the progression of gastric cancer by upregulating the miR-34a/TGIF2 axis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24:11883-11890. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Jafari N, Abediankenari S, Hossein-Nataj H. miR-34a mimic or pre-mir-34a, which is the better option for cancer therapy? Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21:178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Cheng J, Yang A, Cheng S, Feng L, Wu X, Lu X, Zu M, Cui J, Yu H, Zou L. Circulating miR-19a-3p and miR-483-5p as Novel Diagnostic Biomarkers for the Early Diagnosis of Gastric Cancer. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:e923444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Liu M, Wang Z, Yang S, Zhang W, He S, Hu C, Zhu H, Quan L, Bai J, Xu N. TNF-α is a novel target of miR-19a. Int J Oncol. 2011;38:1013-1022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Wa Q, Li L, Lin H, Peng X, Ren D, Huang Y, He P, Huang S. Downregulation of miR19a3p promotes invasion, migration and bone metastasis via activating TGFβ signaling in prostate cancer. Oncol Rep. 2018;39:81-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Su YF, Zang YF, Wang YH, Ding YL. MiR-19-3p Induces Tumor Cell Apoptosis via Targeting FAS in Rectal Cancer Cells. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2020;19:1533033820917978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Cui M, Yue L, Fu Y, Yu W, Hou X, Zhang X. Association of microRNA-181c expression with the progression and prognosis of human gastric carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2013;60:961-964. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Hu X, Miao J, Zhang M, Wang X, Wang Z, Han J, Tong D, Huang C. miRNA-103a-3p Promotes Human Gastric Cancer Cell Proliferation by Targeting and Suppressing ATF7 in vitro. Mol Cells. 2018;41:390-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Wang S, Han H, Hu Y, Yang W, Lv Y, Wang L, Zhang L, Ji J. MicroRNA-130a-3p suppresses cell migration and invasion by inhibition of TBL1XR1-mediated EMT in human gastric carcinoma. Mol Carcinog. 2018;57:383-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |