INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has spread rapidly worldwide and poses a serious threat to healthcare systems globally. It is common to encounter patients with both COVID-19 and abnormal liver function. Because COVID-19 is a newly discovered disease, additional data are needed to improve our understanding of its impact on the liver and of the appropriate management of such patients[1-15]. Information on how COVID-19 infection affects the liver and the relevance of pre-existing liver disease in acquiring the infection or developing severe disease is increasing, although we still do not know the exact mechanism. Additionally, considerations with regard to liver transplant patients, those with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and those under immunosuppressive therapy are being analyzed as information is being generated. Various treatments for COVID-19 are currently under study but some of these may be potentially hepatotoxic[4-6,15].

The first and most evident consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic is its impact on the routine care of patients with chronic liver disease (CLD). The COVID-19 pandemic shifted our perception of ambulatory patient care from face-to-face examinations to virtual patient management[15-18]. Expert recommendations guiding clinicians in the treatment of patients with CLD and of transplanted patients during the pandemic are available in the form of guidelines published by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD)[16-18].

Although patients with CLD are not at higher risk of acquiring the infection, whether COVID-19 and the underlying liver disease will follow an unfavorable course remains to be answered[19]. Nonetheless, questions regarding the treatment of patients with CLD following resolution of the COVID-19 pandemic remain unknown. One must consider that a considerable number of patients with CLD did not attend regular appointments, prevented by fear of acquiring the infection. Preventive, surgical and transplant programs have become secondary focuses. In light of the present circumstances, it is evident that the burdens of the pandemic-related consequences have yet to be elucidated, not only regarding global economics but also global health[19].

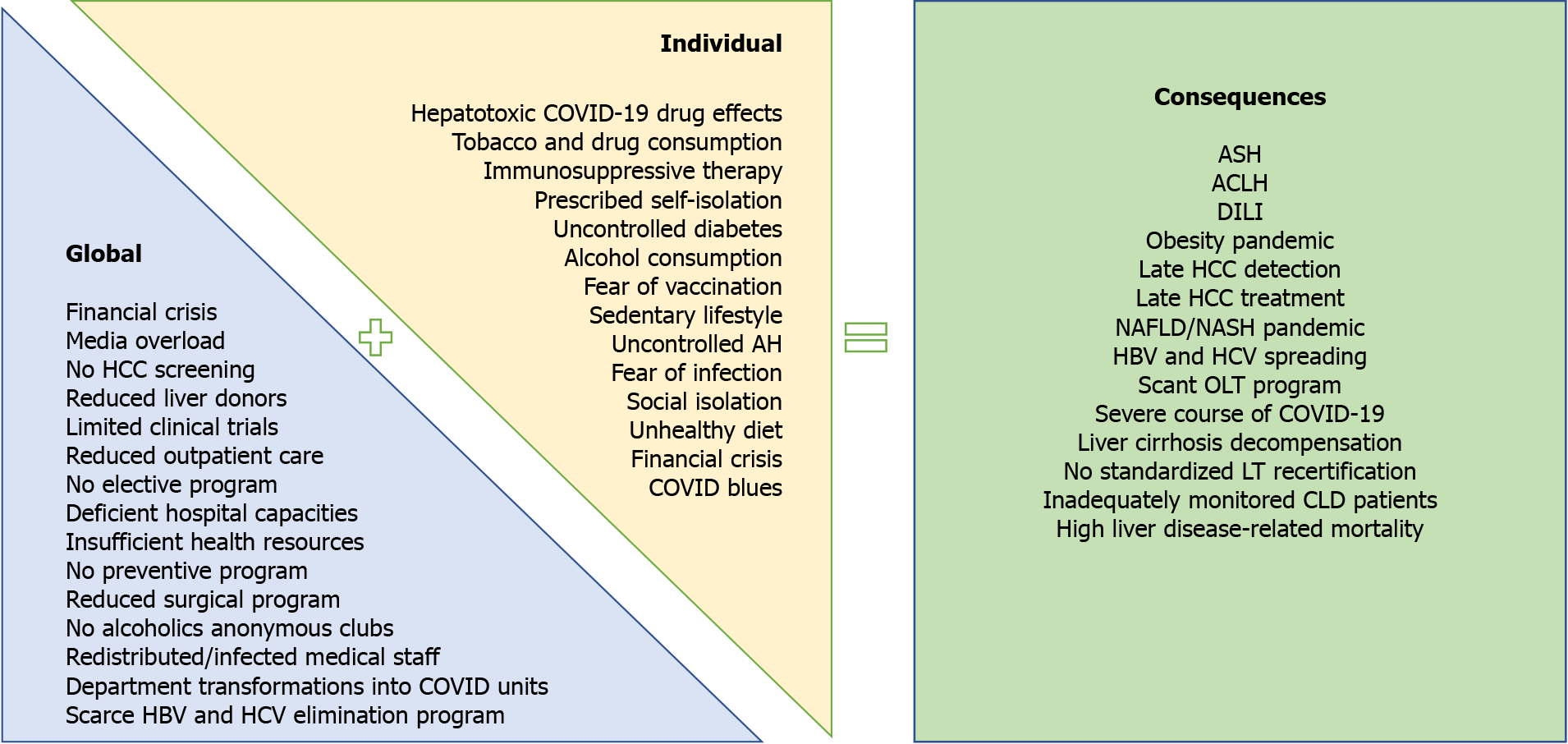

This article reviews the effects of COVID-19 in patients with liver disease during the pandemic, with particular emphasis on the disease course associated with pandemic resolution (Figure 1). We performed a PubMed search using the keywords “chronic liver disease” and “COVID-19”. When using this algorithm there were 396 results. In this review, 74 articles with particular emphasis on COVID-19 and liver disease were analyzed.

Figure 1 Global and individual effects of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on liver-related morbidity and mortality.

ACLF: Acute-on-chronic liver failure; AH: Arterial hypertension; ASH: Alcoholic steatohepatitis; CLD: Chronic liver disease; COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019; DILI: Drug-induced liver injury; HBV: Hepatitis B virus; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV: Hepatitis C virus; NAFLD: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; NASH: Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; OLT: Orthotopic liver transplantation.

PRE-EXISTING CLD AND COVID-19

The reported prevalence of patients with CLD in cohorts of patients with COVID-19 does not exceed 1%, suggesting that the risk of infection acquisition is similar to that in the general population[18,20]. However, the risk of a severe course of disease might be increased due to the etiology of the underlying liver disease along with the degree of liver fibrosis[18].

Liver test abnormalities

According to reports from regular and intensive care units, elevated liver enzymes, lactate dehydrogenase, creatinine kinase and myoglobin, as well as prolonged prothrombin time, are found in more than one-third of patients during COVID-19 progression[21]. A retrospective Chinese study revealed a dynamic pattern of liver molecules regardless of the severity of infection: Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) increased, followed by an increase in alanine aminotransferase (ALT) concurrent with mild oscillations in bilirubin levels. AST levels were significantly associated with mortality risk in this group of patients[22]. Another comprehensive Chinese review also reported elevated AST and ALT levels in 6%-22% and 21%-28% of patients, respectively[23]. Compared to other Chinese regions in which 16% of patients had AST elevation, studies from Wuhan reported a higher percentage, ranging from 24% to 37%. Studies have revealed a high prevalence of liver test abnormalities in men and elderly individuals[23,24]. A large American study including 5700 patients reported that 58.4% of patients had elevated AST levels (> 40 U/L) and 39% had elevated ALT levels (> 60 U/L)[25]. Two percent of patients developed acute hepatic injury and the majority of this subgroup (95%) did not survive[25]. A severe cholestatic pattern has not been reported as correlating with COVID-19 but studies have reported hyperbilirubinemia in 11%-18% of cases[21].

Several pathological mechanisms are considered to be involved in liver injury, including direct viral infection of liver cells, drug hepatotoxicity, cytokine storm and pneumonia-associated hypoxia[15,26,27]. According to several studies, the expression of ACE2 receptors on liver cells facilitates SARS CoV-2 entrance; expression is increased in bile duct cells, whose destruction appears to be primarily responsible for COVID-19-related liver injury[15,26]. Studies clarifying the exact mechanisms of liver injury are warranted[15,27-30].

It must be considered that elevated aminotransferases might be of cardiac or muscular origin and that abnormalities in liver tests are frequently transient. On the other hand, studies have reported an increased risk of severe disease in patients who present with liver injury on admission[15,28]. The severity of liver dysfunction seems to be closely associated with the severity of COVID-19[15]. As predicted by multiple studies, the usual culprits of pathological biochemical liver abnormalities are underlying CLD, sepsis-related cholestasis and drug hepatotoxicity[6]. We must not ignore the fact that the frequency and severity of liver injury in asymptomatic individuals and patients under out-of-hospital treatment remains unknown[6]. Therefore, further investigations are needed to strengthen conclusions.

Finally, the most crucial question for clinicians treating COVID-19 patients is in whom and how often to perform liver function tests. The optimal interval has not yet been defined, but physicians should certainly be attentive when treating severely ill patients and individuals taking novel antiviral drugs such as remdesivir or tocilizumab[6].

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and COVID-19

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), also known as metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease, is a common manifestation of metabolic syndrome and is remarkably prevalent in Western industrialized countries[21]. It is usually comorbid with obesity, which represents a significant risk factor for severe COVID-19 pneumonia[3,18,31]. The assumed mechanism relies on the immunological properties of adipose tissue, which also plays a role as a viral reservoir[3,18,25]. Additional risk factors accompanying NAFLD, such as arterial hypertension, obesity and diabetes, are also commonly observed in patients with a severe COVID-19 course[3,18,25].

As predicted in several studies, patients with NAFLD seem to have a longer period of viral replication and dispersion[32] and experience progression to the severe form of disease, with worsening dyspnea, hypoxia and typical radiological findings [32], even in younger patients without other comorbidities[33,34]. Among patients with NAFLD, the underlying liver fibrosis seems to correlate with severe COVID-19 presentation, regardless of other metabolic comorbidities[11,21,35]. Targher et al[35] also found an interrelation between advanced liver fibrosis (defined as increased Fibrosis 4 and NAFLD fibrosis scores) and severe COVID-19 presentation in a subgroup of 94 (30.3%) patients with NAFLD. However, Lopez-Mendez et al[36] did not confirm these findings. According to their study, although the prevalence of NAFLD and significant liver fibrosis was high in COVID-19 patients, it was not associated with worse clinical outcomes.

The exact mechanism of NAFLD-associated liver fibrosis leading to an undesired COVID-19 course has not yet been defined but presumably is potentiated by the hepatic release of multiple proinflammatory cytokines, exacerbating the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)-induced cytokine storm[35]. On the other hand, virus-related cytokines might increase the risk of liver inflammation. This interplay of cytokine-related events forms a vicious cycle, making the NAFLD population at very high risk of COVID-19 complications[11,21].

Additional large-scale analyses are needed to determine whether NAFLD is an independent risk factor for severe COVID-19 or whether confounding factors are responsible for the previously published results. Studies based on other available noninvasive methods, including transient elastography and acoustic radiation force impulse-based techniques, are also warranted.

It is also important to note the increased predisposition for drug-induced liver injury in patients with liver steatosis[6]. Antiretrovirals such as lopinavir/ritonavir, antibiotics, antifungal agents and other drugs required to treat acute respiratory distress syndrome and systemic inflammation may induce drug-induced liver injury[37]. The possible mechanism of increased susceptibility in this group of patients is associated with oxidative stress, diminished activity of xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes, mitochondrial malfunction and changes in lipid homeostasis[37-39]. Caution must be taken with steatogenic drugs such as amiodarone, sodium valproate, tamoxifen, methotrexate and frequently used glucocorticoids because they may induce steatohepatitis in predisposed individuals[40].

Finally, the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the social aspects of an individual’s daily routine is the last but not least important undesirable sequela. A sedentary lifestyle, social isolation and increased consumption of processed foods are all metabolic antagonists that are especially unfavorable in patients with NAFLD[18]. The COVID-19 “blues” associated with lockdowns, loss of income and deterioration of socioeconomic status might lead to unhealthy lifestyles and consequently the promotion of obesity and associated metabolic diseases[41]. Therefore, COVID-19 will presumably be an indirect cause of expansion of the NAFLD epidemic[42]. In light of the global psychosociological COVID-19 burden, the Mayo Clinic advocates increased caution against NAFLD-promoting behaviors[42,43].

Increases in body mass index uncontrollable arterial hypertension and underregulated diabetes will certainly contribute to the worsening of NAFLD. It is therefore mandatory to treat associated metabolic comorbidities in these patients[18]. In addition, the deleterious effects of delayed detection of HCC in hepatic steatosis patients are the consequences of missed routine ultrasound examinations.

In conclusion, the EASL suggests considering early admission for all patients with NAFLD and COVID-19[18]. Encouraged by the AASLD guidelines, we recommend regular monitoring of liver function in all hospitalized COVID-19 patients[17,21]. Governments and policy makers should implement certain interventions in response to the increase in NAFLD that will insidiously follow after the COVID-19 pandemic[41]. Finally, when contemplating the introduction of lockdown in the future, the potential consequences on metabolic health should be considered[41].

Autoimmune liver disease and COVID-19

Evidence of the influence of immunosuppressive regimens on the acquisition of COVID-19 is still scarce. However, observational studies have suggested an association between glucocorticoid therapy and a severe COVID-19 course[18,44]. When treating autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) flares, the EASL suggests the administration of budesonide rather than systemic corticosteroid therapy in patients without liver cirrhosis[18]. In the clinical setting of a chronic immunosuppressive regimen it is recommended to continue treatment, except in cases of severe COVID-19, superinfections or lymphopenia that frequently follow SARS-CoV-2 infection[16]. According to the largest study of patients with AIH and COVID-19 infection there were no significant differences in the incidence of major adverse COVID-19 outcomes between patients with AIH and those with other CLD[10]. However, in this study, independent risk factors for adverse events (i.e., death) in these patients were age and baseline liver disease severity. In this study, the use of immunosuppression was not associated with death in AIH patients[10]. Additional studies are needed to determine whether AIH per se or adjacent immunosuppressive treatment affect COVID-19 outcomes[18].

Alcoholic liver disease and COVID-19

Patients with alcohol use disorder (AUD) and alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD) are exemplars of the wide range of potentially negative impacts of COVID-19[45]. Primarily, social isolation and the unavailability of professional help may lead to psychological decompensation and an increased risk of relapse[45]. Depressed immune systems and other underlying comorbidities, including renal failure, obesity, chronic viral hepatitis, sarcopenia, alcoholic cardiomyopathy, tobacco use disorder and many others, make these patients easy targets for viral infection. Finally, according to published data, these patients are more prone to developing interstitial pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome secondary to SARS-CoV-2 infection than their counterparts[18]. Case series of ALD individuals reported a rapid disease course, including bilobar pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome requiring mechanical ventilation, with unfavorable outcomes including cardiopulmonary insufficiency and multiorgan failure[46,47]. Patients admitted for acute alcoholic steatohepatitis (ASH) are usually assessed using Maddrey’s discriminant function (DF) score, with DF > 32 predicting a higher mortality rate[46]. The usual treatment of ASH in patients with DF > 32 using the classical prednisone regimen is an additional risk factor for a severe course of COVID-19 and is therefore not recommended for patients who are self-isolating or considered at high risk of acquiring SARS-CoV-2 infection[45]. Liver impairment is frequently observed in patients with COVID-19[46]. It is also well known that ASH increases the risk of hepatorenal syndrome development, especially after contrast agent application. Cytokine damage, inadequate organ perfusion, nephrotoxic drug effects and nosocomial infections all potentiate the acute kidney injury, usually resulting in the need for continuous renal replacement therapy[47].

In order to obviate the described critical disease course with severe consequences and high mortality rate, we should focus on two main aspects in the care of ALD patients. The primary focus is the prevention, of infection by following strict epidemiologic recommendations, as well as the prevention of AUD relapse by implementing vigorous social and psychiatric care by telephone. The unavailability of support groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous should be bridged using individual or smaller group treatment[47]. The secondary focus is the prevention of a deleterious disease course using vigilant intrahospital clinical care and timely recognition of hepatobiliary, renal and respiratory complications[18].

Viral hepatitis and COVID-19

Whether chronic viral hepatitis specifically affects the COVID-19 course remains unknown. In a retrospective Italian multicenter study that included 50 patients with liver cirrhosis and SARS-CoV-2 infection, 28% had hepatitis C virus (HCV)-related cirrhosis and 10% had hepatitis B virus (HBV)-related cirrhosis. The patients were either HCV-RNA negative after anti-HCV treatment or on long-term anti-HBV treatment. The severity of liver disease was an independent predictor of mortality[29]. The same conclusion was derived from an international registry that included 152 patients with CLD and COVID-19, among which 22.5% of the CLD was due to chronic HBV or HCV infection[30].

In the last year, the COVID-19 outbreak has redirected attention from other morbidities, including viral hepatitis: as a consequence of this pandemic, most viral hepatitis elimination programs have diminished or stopped altogether[14,19,48,49]. The World Health Organization’s goal of eliminating HBV and HCV and thus significantly reducing the associated mortality until 2030 has therefore been put on hold. Elimination programs are already scarce, as well as involvement by liver disease societies, epidemiologists, infection specialists and general practitioners, despite the WHO Global Hepatitis Report 2017 stating that the viral hepatitis global mortality is 1.5 million per year[19,48,49]. Preventing mother-to-child transmission and promoting blood safety are presumably the only intact weapons in the battle against HBV and HCV[19,48]. Although we will realize the full impact of reducing or delaying programs targeting hepatitis elimination in the near future, there are some mathematical models that can predict the possible impact on the global burden of viral hepatitis and hepatitis-associated morbidity and mortality that will result as a consequence of program delay[49]. A recent study used certain mathematical models to analyze the impact of delayed programs on viral hepatitis elimination[49]. The authors reported that a 1-year delay in viral hepatitis diagnosis and treatment will result in an additional 44800 HCC cases as well as 72300 deaths from HCV globally in the next 10 years[49].

If we cannot make progress in achieving the aforementioned elimination goals due to the COVID-19 crisis, then education campaigns, extensive screening, diagnostic tests, vaccination programs and treatment should at least be maintained at the former level[19,48,49].

Liver cirrhosis and COVID-19

Patients with liver cirrhosis, particularly decompensated cirrhosis, are by far the most vulnerable liver disease patients. Immune dysfunction makes them prone to any kind of infection, including SARS-CoV-2, with potentially deleterious effects on the disease course. Data suggest that the course of COVID-19 is directly connected to the degree of liver disease defined by the Child-Pugh (CP) and Model for End Stage Liver Disease scores[18].

An international registry including 103 patients with liver cirrhosis reported a 40% mortality rate, strongly correlated with the grade of liver failure: 23.9% mortality in patients with CP class A, 43.3% mortality in patients with CP class B and 63.0% mortality in patients with CP class C cirrhosis[50]. Similarly, an Italian study involving 50 patients with liver cirrhosis suffering from COVID-19 found a 30-d mortality rate of 34%, among which 71% of patients died due to COVID-related respiratory failure[51].

The largest published study to date was based on two international registries and included 745 patients with CLD (among which 52% had liver cirrhosis) and acute COVID-19 infection. When compared to the data of non-CLD patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection in a UK hospital network, a statistically significant difference in mortality (P < 0.001) was reported: 32% in patients with liver cirrhosis compared to 8% in those without[52]. The main cause of death was respiratory failure, with acute decompensation of liver cirrhosis occurring in 46% of patients. The authors concluded that the CP score and ALD were independent risk factors for death due to COVID-19[52].

A prospective American multicenter study by Singh and Khan[53] compared patients with both liver cirrhosis and COVID-19 to patients with only COVID-19 and found a significant difference in the outcome (30% vs 13%, P = 0.03). However, the fact that there was no significant difference in the outcomes of patients with liver cirrhosis regarding COVID-19 infection is intriguing. It seems important to emphasize that the proportion of SARS-CoV-2-positive cirrhosis patients in this study was approximately three times lower than that in the other two subgroups.

In summary, in patients suffering from COVID-19, mortality is significantly greater in those with liver cirrhosis than in those without and is directly related to the stage of liver failure[18]. However, it remains unclear whether COVID-19-related mortality is higher than that related to other causes of decompensation that are often also infective in origin[18].

Liver cirrhosis causes 2 million deaths globally per year. Prevention of liver decompensation and prompt diagnosis and treatment of cirrhosis-related complications are of the utmost importance[54,55]. Management with endoscopic variceal screening, primary and secondary prophylaxis, implementation of telecommunication and electronic communication in drug titration, especially regarding beta-blockers and diuretic therapies, is warranted. HCC screening and diagnostic persuasion, including radiologic methods and liver biopsy, as well as therapeutic treatments ranging from radiofrequency ablation to liver transplantation (LT), should be preserved despite scarce resources, physician burnout and lack of hospital capacity[54,55].

Tapper and Asrani[55] proposed a three-wave theory to explain the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on liver cirrhosis from the current period to future years. The first wave describes the period of physical distancing and is defined by high-acuity care and delayed elective procedures[55]. For example, patients with esophageal varices are admitted only for bleeding episodes, and elective endoscopic band ligation (EBL) is not performed due to fear of viral spread and limited healthcare resources. The direct consequence of the first phase is the second wave, appearing after the resolution of physical distancing and characterized by a high frequency of cirrhosis decompensation[55]. Continuing with the given example, a substantial number of patients with indefinitely delayed or skipped EBL procedures will begin to experience variceal bleeding episodes, leading to cirrhosis decompensation or even acute-on-chronic liver failure. Accessible, inexpensive, processed foods rich in salt, as well as alcoholic beverages, both highly consumed during pandemics, will result in the exacerbation of volume overload and also potentiate sarcopenia, which is a well-known risk factor for cirrhosis-associated morbidity and mortality[55]. The third wave will presumably comprise long-term complications. Delayed diagnosis of hepatobiliary malignancies, progression of HCC reaching the Milan criteria and the consequent elimination of patients from transplant lists, insidious deterioration of renal function, no standardized recertification of patients awaiting LT and many more complications are to be encountered. As Tapper and Asrani[55] stated, the curable will be transformed into the incurable.

HCC and COVID-19

Although there are no specific data on the outcomes of patients with HCC and COVID-19 infection, it is assumed that HCC patients will have poor outcomes, similar to those in other oncology patients[15]. However, we know that most HCC patients have pre-existing CLD and in comparison to other patients with cancers we can assume that such patients are more susceptible to the effects of COVID-19: that is, hepatic injury caused by COVID-19 can complicate existing CLD in most patients with HCC. The COVID-19 pandemic has greatly limited the medical care of HCC patients, with effects ranging from early diagnosis to treatment. As ultrasound screening examinations have mostly been delayed indefinitely, without precise upcoming appointment dates and resulting in prolonged periods without control, the risk of discovering HCC at a later stage increased in approximately 25% of patients with the biologically aggressive type of disease[55,56].

Elective hospital admissions were also delayed in the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic due to low hospital capacity and the fear of viral spread. Outpatient ambulatory care was unavailable for a certain time. Subsequently, a substantial number of patients were afraid to visit medical facilities. Therefore, diagnostic procedures such as contrast-enhanced ultrasound, multislice computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging and liver biopsies have been delayed. Additionally, treatment options have been insufficiently maintained. Surgical resection and LT are the most affected due to a shortage of anesthetists and other medical personnel[6]. Procedures such as transarterial (chemo)embolization (TACE/TAE) and radiofrequency ablation are therefore the most important tools in treating patients with HCC. Data on the impact of COVID-19 on HCC patient care are underrepresented[56,57]. A colleague from an Italian center managed HCC patients with the goal of minimizing the impact of COVID-19 and reported their experience from February 24 to March 20, 2020, regarding the treatment of HCC patients in comparison to the same period during 2019[57]. The authors found that 11% of patients had delayed treatment of HCC for 2 mo or longer. The delayed treatment modalities comprised transarterial procedures in eight HCC patients, thermal ablation in three HCC patients and systemic therapy in two patients. Thermal ablation in the three patients was performed as an alternative procedure to surgical treatment. The results of this study represent the best efforts of clinicians to manage HCC during the COVID-19 pandemic[57].

In the case of early-stage HCC, the capacity of most hospitals for surgical treatment (resection) is limited due to the limited number of anesthesiologists as well as shortages in intensive care unit beds. Clinicians can select some patients who have been prioritized for resection and have a relatively low disease burden. Treatment modalities such as radiofrequency and microwave ablation, upfront transarterial treatment and systemic therapy may be considered as alternative methods according to the guidelines for each treatment modality[56,58]. Additionally, during the pandemic, the number of LTs were reduced or reached zero for some time due to reduced anesthetic capacity as well as a shortage of donors[56,58]. In the case of intermediate-stage HCC, a more selective approach can be used with respect to TACE in hospitals that are greatly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, if a specific center cannot perform TACE, systemic therapy or adequate surveillance, then imaging could be an alternative approach[56,58]. Finally, in the case of advanced-stage HCC, HCC patients who receive oral multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors could be followed by clinicians for prolonged intervals or monitored by telephone or another telemedicine interface, depending on the patient’s tolerance and clinical status during the COVID-19 pandemic[56,58]. The impact on the long-term outcomes of HCC due to these modifications in treatment options, as well as the delays in treatment, will soon be realized[57].

The decision to treat HCC during the pandemic should consider the availability of medical staff, risk of infection and the risk-benefit ratio for an individual patient. The management of HCC in patients is complex because it relies heavily on multidisciplinary approaches involving gastroenterologists, radiologists, hepatobiliary surgeons and oncologists, who are significantly burdened during this pandemic[15,56]. Extra coordination among different specialties is necessary to maintain clinical services for patients with HCC. It is recommended that the care and treatment of HCC patients is maintained according to the guidelines by using alternative methods of communication whenever possible in order to minimize the COVID-19 exposure risk to medical staff[15]. Widely available SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction testing is recommended before elective hospital admission, although there can never be a definite guarantee for medical personnel because a patient may be in the incubation phase of infection or the patient may contract the infection in the hospital. If the patient is acutely infected, it is reasonable to defer HCC treatment for a few weeks until after recovery from COVID-19[6].

LT AND COVID-19

LT programs have been weakened globally, even in regions where the COVID-19 prevalence has been low[59-61]. During this period of readjustment no specific guidelines were offered; however, multiple organizations released recommendations for medical personnel involved in solid organ transplantation[59-66].

Primarily, obtaining an organ from a SARS-CoV-2-infected patient is contraindicated. Moreover, screening of deceased donors, as well as recipients, is highly recommended[59-66]. In the case of unidentified infection, the donor could spread the virus to multiple recipients, which would presumably have an unfavorable or even lethal course under severe immunosuppression[6,62].

As the risk of contracting the virus is high, even under hospital conditions, it would be appropriate to limit the number of face-to-face contacts for patients at risk of severe COVID-19. They should be advised against travel and should strictly practice physical distancing[6]. Due to cirrhosis-associated immune dysfunction, the aforementioned recommendations apply to all patients awaiting transplantation.

A further challenge is related to the staff involved in LT, who cannot be easily replaced. Quarantined, infected or redistributed personnel can prevent program realization for a certain period of time, which can have deleterious effects on potential LT recipients[59]. Therefore, splitting the team involved in LT and postoperative care into smaller subteams, as well as screening and segregating staff working with immediate post-LT patients, is recommended[59]. Compared to some other solid organ transplantations, LT is performed to preserve life. In contrast, although renal transplantation reduces dialysis morbidity and future medical costs, it is not directly lifesaving and can therefore be postponed[62]. Lifesaving transplantations, such as liver, heart and lung, have far more urgent indications and postponement may have deleterious consequences. Accordingly, it is of utmost importance that LT centers worldwide aim to restore their transplantation services.

Finally, according to preliminary data, age and comorbidity are key to determining the outcome from SARS-CoV-2 infection in LT patients[6,9].

Whether to receive vaccination is currently an unavoidable global question potentiated by substantial social media involvement. Three vaccines were approved by February 2021. Two of these, the BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) and mRNA-1273 (Moderna) vaccines, are based on mRNAs that encode variants of the SARS-CoV-2-spiked glycoprotein[63]. Both must be administered twice, 21-28 d apart. The third approved vaccine is AZD1222, also known as the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine. This is an adenovirus vector that contains the full-length, codon-optimized gene that encodes the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and should also be administered in two doses, with the second dose administered 4-12 wk after the first dose[63]. The EASL position paper recommends vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 in patients with CLD, hepatobiliary cancer and LT[63].

Post-transplant patients and COVID-19

Patients taking immunosuppressive drugs after transplantation are at increased risk of infection or viral reactivation. The exact influence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in post-LT patients is unclear[15].

Regarding the disease course in post-transplant patients, it seems that immunosuppression might have favorable effects by disabling cytokine release syndrome, characterized by increased serum levels of interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8 and tumor necrosis factor[15,64]. A Spanish study analyzed 111 LT patients diagnosed with COVID-19[65]. During a median follow-up of approximately 3 wk, 86.5% of patients were admitted to hospital, among which 19.8% required respiratory support[65]. Surprisingly, their mortality rate (18%) was lower than in the complementary general population. Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) administered at a dose of > 1000 mg/d was an independent predictor of severe COVID-19[65]. In contrast, treatment with calcineurin inhibitors and the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor everolimus were not associated with a severe COVID-19 course. Complete withdrawal of immunosuppression showed no benefit[65]. Therefore, MMF withdrawal or transient conversion to calcineurin inhibitors or everolimus could be beneficial for hospitalized patients until the COVID-19 resolves[65].

Vaccination in post-LT patients is recommended at approximately 3-6 mo after transplantation when immunosuppression can be reduced. This is because the immune system is too suppressed to mount the proper vaccination response in the early post-transplant period. Accordingly, vaccination of household members and of healthcare professionals caring for immunocompromised patients is advocated[63].

CONCLUSION

The global social, economic and political crises related to the COVID-19 pandemic presumably had more indirect than direct negative impacts on health systems. Drastic lifestyle changes, social isolation and distancing, and individual and global financial crises resulted in a robust population forfeiting healthy habits and seeking comfort in alcoholic beverages, drugs and unhealthy diets[19,41]. The inevitable consequences are the rising incidence of NAFLD, viral hepatitis, acute alcoholic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis decompensation and ultimately liver-related mortality[19].

The inaccessibility of regular clinical and sonographic examinations has resulted in difficulties in the treatment of patients with CLD or prompt HCC detection and treatment. A dramatic reduction in the number of liver donors and the transformation of numerous transplantation centers into COVID-19 units have greatly reduced the rate of orthotopic LT.

The indirect unavoidable effects of the COVID-19 pandemic in the following years have yet to be determined[19]. Although the health system has been tremendously challenged, resulting in overwhelming damage that is continuously being revealed, focus should remain on the current and upcoming periods involving patients with uncontrolled chronic diseases[16,19]. Swift resumption of care practices, especially for patients with HCC or individuals requiring LT, must be initiated while simultaneously maintaining social distancing and balancing inadequate hospital resources[16,19].

Substantial efforts should be initiated for the management of patients with liver disease in order to prevent and control the inevitable COVID-19-related morbidity and mortality that will follow.

Several questions regarding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on liver disease remain. One of the most important questions is: What will be the effect of long-term anticoagulants on liver disease? The main question for general CLD patients is: How will the modification of clinical practice during this pandemic affect outcomes in CLD patients.