Published online Sep 7, 2021. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i33.5595

Peer-review started: April 6, 2021

First decision: June 24, 2021

Revised: July 9, 2021

Accepted: August 12, 2021

Article in press: August 12, 2021

Published online: September 7, 2021

Processing time: 150 Days and 5.9 Hours

Despite its decreased incidence in Japan, gastric cancer continues among the leading causes of cancer-related deaths in both men and women. Accordingly, efforts are still required to lower the mortality rate of gastric cancer in Japan. Maebashi City introduced endoscopic gastric cancer screening in 2004, and par

To evaluate the impact on gastric cancer mortality rate of two types of gastric cancer screening in Maebashi City, Japan.

Participants aged 40 to 79 years of the Maebashi City gastric cancer screening program in 2006 who were screened by direct radiography (n = 11155) or endo

Gastric cancer was detected in 22 participants undergoing direct radiography (detection rate, 0.20%) and in 52 participants undergoing endoscopy (detection rate, 0.48%). However, most gastric cancers detected by endoscopic screening were early cancers that may not have resulted in death. We found no significant difference in gastric cancer mortality rate between participants receiving annual screening and those who do not. When the number of gastric cancer deaths in the direct radiography group was set as 1 in the Cox proportional hazard analysis, the HR of gastric cancer death was 1.368 (95%CI: 0.7308–2.562) in the overall group of participants. The results showed no significant difference between the two scree

Although endoscopic screening detected more gastric cancer than direct radio

Core Tip: Although the incidence rate has declined in Japan, gastric cancer is still the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in men and women. Therefore, Japan still needs to work hard to reduce the death rate of gastric cancer. Maebashi City introduced endoscopic gastric cancer screening in 2004. Endoscopic screening detects more gastric cancer than direct radiographic screening does, but both screening methods have similar effects on reducing the mortality rate from gastric cancer.

- Citation: Hagiwara H, Moki F, Yamashita Y, Saji K, Iesaki K, Suda H. Gastric cancer mortality related to direct radiographic and endoscopic screening: A retrospective study. World J Gastroenterol 2021; 27(33): 5595-5609

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v27/i33/5595.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v27.i33.5595

In 2017, 24.5 million patients globally had a cancer diagnosis, and 9.6 million patients died of cancer. Of these deaths, 861000 were due to gastric cancer (men, n = 542000; women, n = 319000). Furthermore, gastric cancer was the third-highest cause of death among men dying from cancer and the fourth-highest in women dying from cancer[1].

In Japan, the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori (Hp) infection—a known cause of gastric cancer—has decreased, and the incidence of gastric cancer and the age-adjusted mortality rate from gastric cancer have also been decreasing. Nonetheless, in 2018 gastric cancer was the second-highest cause of death among Japanese men dying from any cancer and the fourth-highest among Japanese women dying from any cancer[2]. Accordingly, further efforts are still required to lower the mortality rate of gastric cancer in Japan.

In Japan, for many years, gastric cancer mass screening programs conducted by municipal governments were performed by using indirect radiography to examine large numbers of people, and direct radiography was used to examine individual patients at medical institutions. However, in 2015 the Gastric Cancer Screening Guidelines were revised to recommend endoscopy for organized gastric cancer scree

In Maebashi City, endoscopic gastric cancer screening was introduced in 2004, and subsequently, participants were able to choose between direct radiography and en

Citizens aged 40 years and older are eligible to participate in the Maebashi City gastric cancer screening as part of their personal health check, and participants can choose between direct radiography and endoscopy every year. Gastric cancer screening is conducted at practitioner clinics or at hospitals in Maebashi City that have elected to participate in the screening program, and institutions do not have to fulfill any eli

The present study included participants aged 40 to 79 years; 79 years was chosen as the upper age limit because, in Japan, the average lifespan is 79.00 years in men and 85.81 years in women[5]. A total of 21802 participants were included, comprising 11155 individuals who underwent direct radiography and 10747 who underwent en

First, we investigated the number of gastric cancers detected and the cancer stage at detection. Next, we compared the detection rate between the two participant groups undergoing direct radiography or endoscopy. Then, we compared the mortality rate between the two groups. The clinical data of the present study cohort, including the name, sex, date of birth, and history of participation in gastric cancer screening, were extracted from the Maebashi Medical Association cancer screening database. The participants were followed up until March 31, 2012, using the Gunma Prefectural Cancer Registry data. The 2006 Maebashi City gastric cancer screening was conducted from May 2006 until the end of February 2007, and participants could choose to be screened by either of the two imaging methods. The follow-up period ranged from 5 years, 1 mo, to 5 years, 11 mo.

The two screening methods are offered by at least 80 institutions each year. Direct radiographic examination is performed by the standard imaging method (8-image method). For endoscopic gastric cancer screening, 30 to 40 images are taken that cover the esophagus and duodenum. Screening physicians are required to submit the images to the Maebashi Medical Association, where they are reviewed by two other physi

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the re

The primary outcome was death from gastric cancer. We compared the incidence rate of the primary outcome between the two screening methods in the whole group of participants and between those participants who had also participated in the gastric cancer screening in the previous year and those who had not.

The secondary outcome was the incidence rate of death from any cancer except gastric cancer, and the same comparisons were performed for the secondary outcome as for the primary outcome.

To obtain additional information on causes of death, we compared the data in the Gunma Prefectural Cancer Registry with the death certificates.

The accuracy of the 2006 Gunma Prefectural Cancer Registry was low with 40.5% of incidence cancer rate registered as death certified only; however, the data of death was perfectly obtained.

We compared the participants’ background factors between the two groups using Fisher’s exact test and Student’s t-test. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate the hazard ratio (HR) of gastric cancer death, and death from any cancer other than gastric cancer, in the overall group of participants and the subsets of participants who had or had not participated in gastric cancer screening in the pre

The percentages of male participants and participants aged 60 years or older were slightly higher in the endoscopic screening group (Table 1). Similar results were found in the subsets of participants who had also participated in the screening in the pre

| Screening method | ||||

| Endoscopy | Radiography | P value | ||

| Participants, n | 10747 | 11155 | ||

| Sex, n (%) | Male | 4323 (40.2) | 4103 (36.8) | < 0.001 |

| Female | 6424 (59.8) | 7052 (63.2) | ||

| Age group, n (%) | 40–49 yr | 952 (8.9) | 1005 (9.0) | NA |

| 50–59 yr | 2043 (19.0) | 2264 (20.3) | ||

| 60–69 yr | 3667 (34.1) | 3986 (35.7) | ||

| 70–79 yr | 4085 (38.0) | 3900 (35.0) | ||

| Age group, n (%) | 40–59 yr | 2995 (27.9) | 3269 (29.3) | 0.019 |

| 60–79 yr | 7752 (72.1) | 7886 (70.7) | ||

| Age, mean (SD), yr | 64.75 (9.69) | 64.30 (9.57) | < 0.001 | |

| Screening method | ||||

| Endoscopy | Radiography | P value | ||

| Participants, n | 6915 | 4382 | ||

| Sex, n (%) | Male | 2680 (38.8) | 1570 (35.8) | 0.002 |

| Female | 4235 (61.2) | 2812 (64.2) | ||

| Age group, n (%) | 40–49 yr | 764 (11.0) | 552 (12.6) | NA |

| 50–59 yr | 1483 (21.4) | 1032 (23.6) | ||

| 60–69 yr | 2372 (34.3) | 1528 (34.9) | ||

| 70–79 yr | 2296 (33.2) | 1270 (29.0) | ||

| Age group, n (%) | 40–59 yr | 2247 (32.5) | 1584 (36.1) | < 0.001 |

| 60–79 yr | 4668 (67.5) | 2798 (63.9) | ||

| Age, mean (SD), yr | 63.54 (9.99) | 62.51 (10.08) | < 0.001 | |

| Screening method | ||||

| Endoscopy | Radiography | P value | ||

| Participants, n | 3832 | 6773 | ||

| Sex, n (%) | Male | 1643 (42.9) | 2533 (37.4) | < 0.001 |

| Female | 2189 (57.1) | 4240 (62.6) | ||

| Age group, n (%) | 40–49 yr | 188 (4.9) | 453 (6.7) | NA |

| 50–59 yr | 560 (14.6) | 1232 (18.2) | ||

| 60–69 yr | 1295 (33.8) | 2458 (36.3) | ||

| 70–79 yr | 1789 (46.7) | 2630 (38.8) | ||

| Age group, n (%) | 40–59 yr | 748 (19.5) | 1685 (24.9) | < 0.001 |

| 60–79 yr | 3084 (80.5) | 5088 (75.1) | ||

| Age, mean (SD), b | 66.95 (8.71) | 65.46 (9.03) | < 0.001 | |

Among all screening program participants, gastric cancer was detected in 25 par

In the participants aged from 40 to 79 years, the categories of gastric cancer lesions detected by direct radiographic screening and respective numbers and percentages of participants were as follows: Stage IA, n = 6 (27.2%); stage IB, n = 2 (9.1%); stage II, n = 3 (13.6%); stage IIIA, n = 1 (4.5%); stage IIIB, n = 4 (18.2%); stage IV, n = 5 (22.7%); and unspecified stage, n = 1 (4.5%). The respective data for gastric cancer detected by endoscopic screening were as follows: Stage IA, n = 30 (57.7%); stage IB, n = 3 in

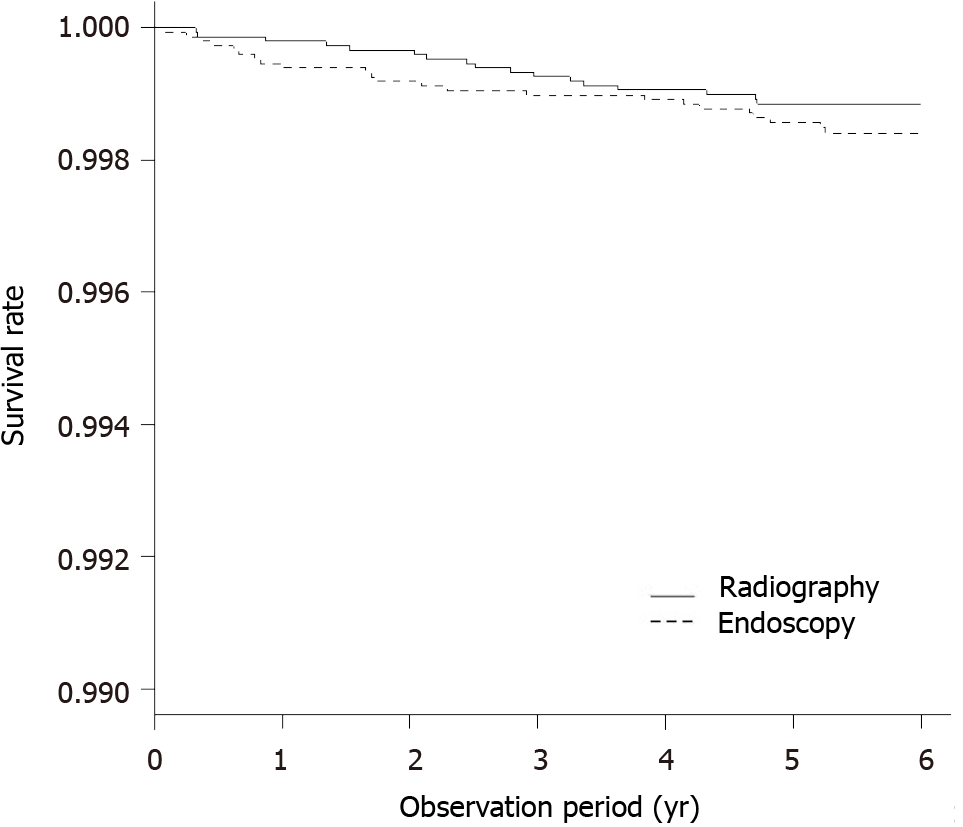

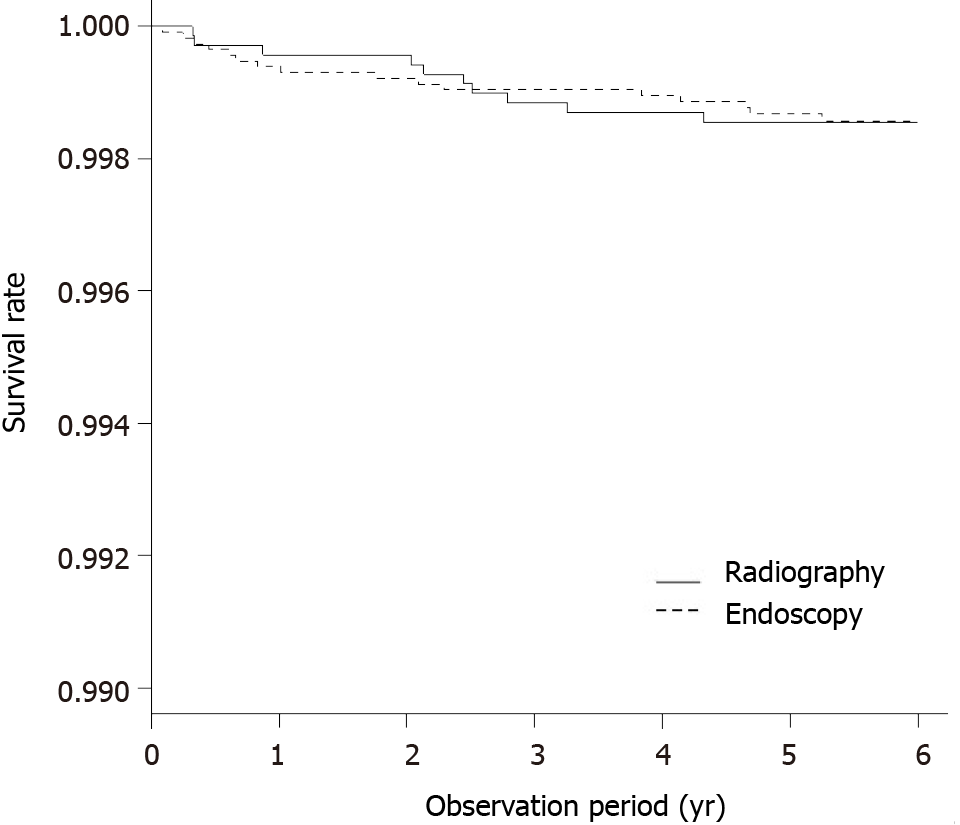

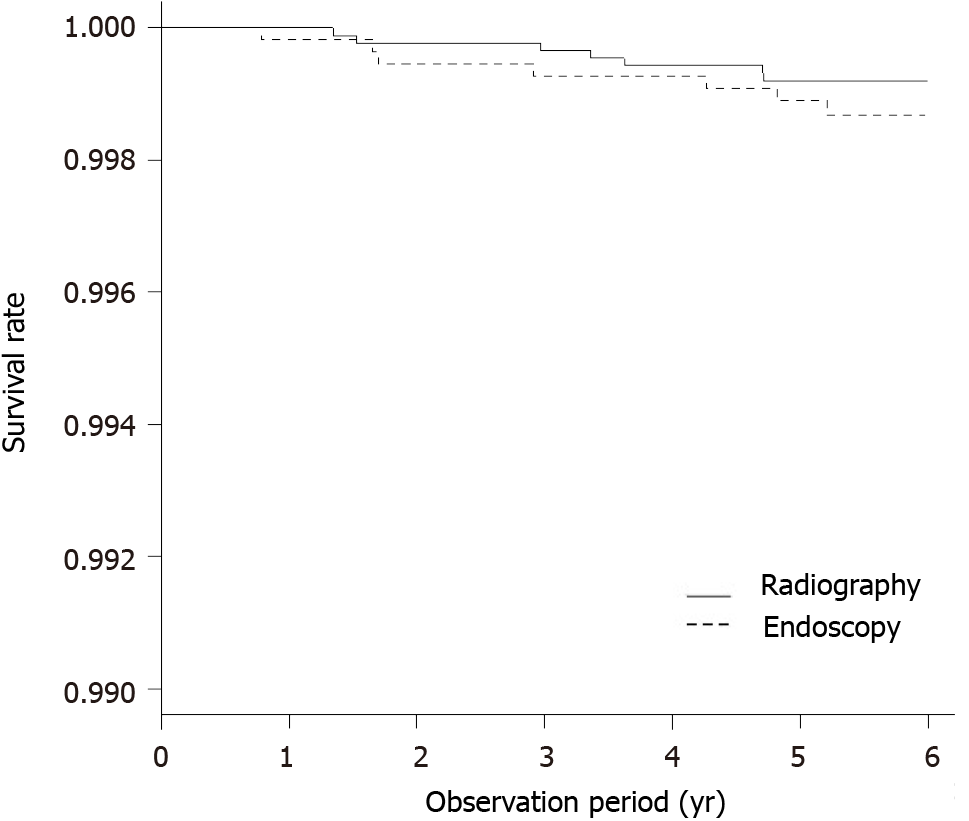

Gastric cancer deaths were detected in 17 of the 11 155 individuals who underwent direct radiography and in 23 of the 10 747 individuals who underwent endoscopy. The five-year survival by the Kaplan-Meier method was 0.998 (95%CI: 0.998–0.999) in individuals who underwent direct radiography and 0.998 (95%CI: 0.997–0.999) in individuals who underwent endoscopy. Overall, no significant difference was ob

A Cox hazard analysis was conducted. Because the proportional hazard was not maintained for participants who had not participated in the previous year, the HR was estimated for participants who had also participated in the screening in the previous year and those who did not. When the number of gastric cancer deaths in the direct radiography group was set as 1 in the Cox proportional hazard analysis, the adjusted HR of gastric cancer death was 1.368 (95%CI: 0.7308–2.562) in the overall group of participants and 1.600 (95%CI: 0.5604–4.569) in the subset of participants who had also participated in gastric cancer screening in the previous year. These results showed no significant difference between the two screening methods in any of the analysis groups (Table 4).

| Screening method | Participants, n (%) | Gastric cancer deaths, n (%) | Adjusted reduction rate1 | 95%CI | |

| All participants | Radiography | 11155 | 17 | 1.000 | |

| Endoscopy | 10747 | 23 | 1.368 | 0.7308–2.562 | |

| Participants receiving annual screening after 2006 | Radiography | 6773 | 7 | 1.000 | |

| Endoscopy | 3832 | 7 | 1.600 | 0.5604–4.569 |

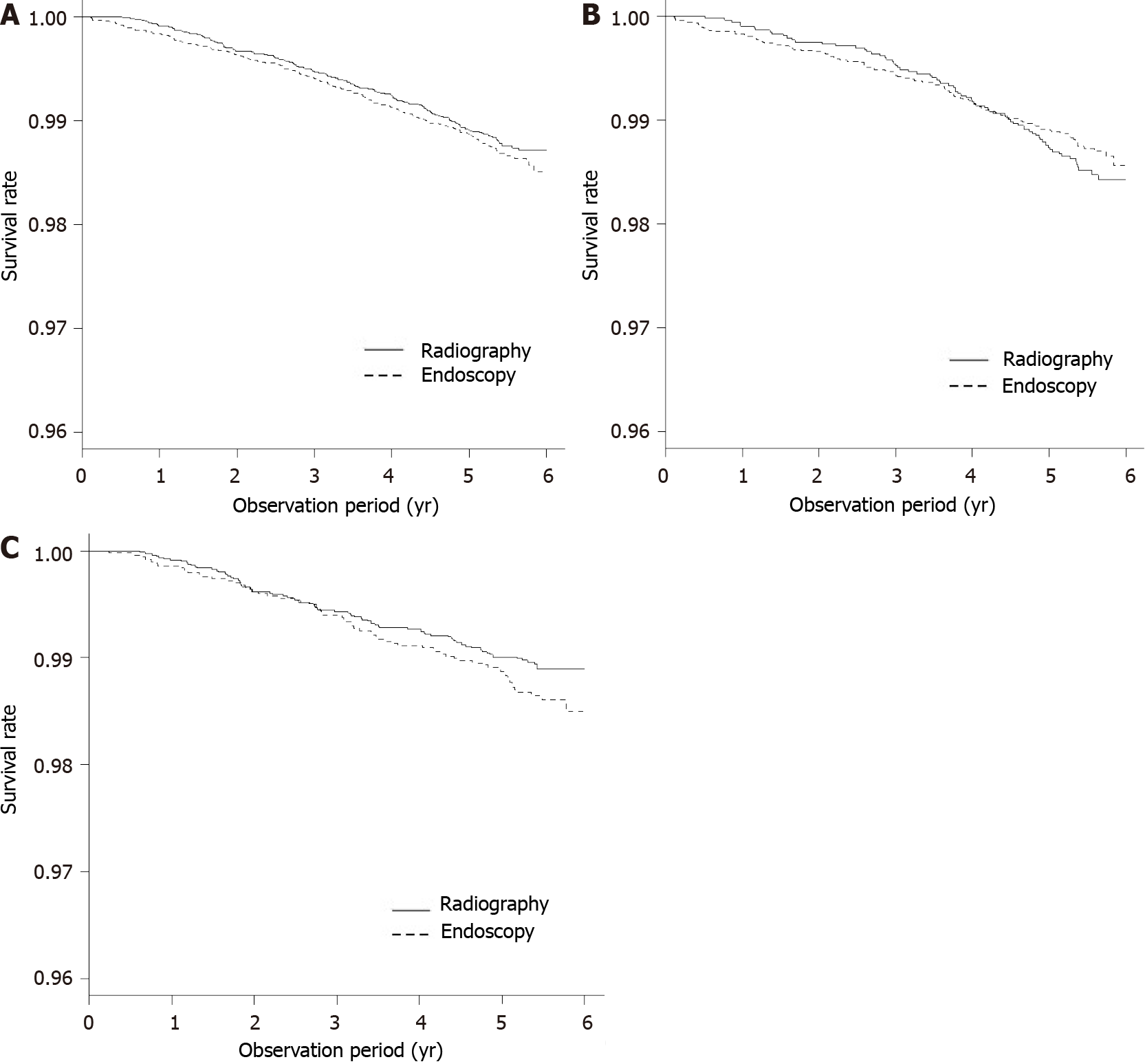

Deaths from any cancer other than gastric cancer occurred in 163 of 11 155 individuals who underwent direct radiography and 178 of 10 747 individuals who underwent endoscopy. The five-year survival rate was 0.987 (95%CI: 0.985–0.989) in individuals who underwent direct radiography and 0.986 (95%CI: 0.984–0.988) in individuals who underwent endoscopy. No significant difference between the two screening methods was observed in the overall population (P = 0.249) (Figure 4A).

Among participants who had not participated in screening in the previous year, gastric cancer deaths were detected in 77 of 4 382 individuals who underwent direct radiography and 110 of 6 915 individuals who underwent endoscopy. The five-year survival rate was 0.985 (95%CI: 0.981–0.988) in individuals who underwent direct radiography and 0.986 (95%CI: 0.983–0.989) in individuals who underwent endoscopy. No significant difference was observed between the two screening methods (P = 0.509) (Figure 4B).

Among participants who had also participated in screening in the previous year, gastric cancer deaths were detected in 86 of 6 773 individuals who underwent direct radiography and 68 of 3 832 individuals who underwent endoscopy. The five-year survival rate was 0.988 (95%CI: 0.985–0.990) in individuals who underwent direct radiography and 0.985 (95%CI: 0.981–0.989) in individuals who underwent endoscopy. A significant difference was observed between the two screening methods (P = 0.038) (Figure 4C). The Cox proportional hazard test was conducted. For participants who had not participated in the previous year, the Cox hazard was not maintained. Ac

When the number of deaths from any cancer other than gastric cancer in the participants who received direct radiographic screening was set as 1 in the Cox proportional hazard analysis, the adjusted HR of deaths from any cancer other than gastric cancer was 1.090 (95%CI: 0.8813-1.3480) in the overall group, 1.284 (95%CI: 0.9334–1.7650) in the participants who had also participated in the screening in the previous year. Again, no significant difference was found between the two screening methods in terms of death from any cancer except gastric cancer (Table 5).

In this study, we examined clinical data from participants in the Maebashi City gastric cancer screening program in 2006 to assess whether the mortality rate from gastric cancer decreased after endoscopy was introduced as an additional screening method in addition to direct radiography. We found that although endoscopy detected more gastric cancers than direct radiography, the mortality rate from gastric cancer showed no difference between the two screening methods. Hence, endoscopy likely detected relatively slowly progressing gastric cancer (mainly differentiated gastric cancer common in older adults), whereas failed to detect gastric cancer that rapidly pro

Hamashima et al[10] performed a study, the Tottori Cohort Study, on data from gastric cancer screening by radiography and endoscopy conducted in Yonago City and Tottori City in 2007 and 2008[10]. This study included people aged 40 to 79 years who had not participated in gastric cancer screening in the previous year and followed them until the end of 2013 by using data from the Tottori Prefectural cancer registry. The authors reported that endoscopic screening reduced the gastric cancer mortality rate by 67% compared with radiographic screening[10]. In contrast, our study results found that the introduction of endoscopy in an organized gastric cancer screening program did not significantly reduce the gastric cancer mortality rate compared with direct radiographic screening. In Tottori Prefecture, institutions are allowed to conduct endoscopic screening if they perform at least 50 endoscopies annually, submit ar

Endoscopy of the upper gastrointestinal tract has become the more common evaluation method in routine clinical care in Japan. In 2014, endoscopies were per

In Japan, endoscopies are not always performed by endoscopists with specialized training in the procedure, particularly at general clinics, and most of the general clinics in Maebashi City that routinely perform endoscopies participated in the 2006 gastric cancer screening. In this study, endoscopies were performed by endoscopy experts only at 22 of the 82 participating clinics. Shimodate et al[13] reported that expert physicians certified by the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society detected gastric cancer in 1462 patients and that the gastric cancer lesions had been missed in the previous endoscopies in 157 of these patients; in 13 of the 157 patients, the lesion had progressed to advanced gastric cancer at the time of detection. Hosokawa et al[14] evaluated the precision of endoscopy for cancer detection and found a false-negative rate during the three years after endoscopy of 22.2%. They also reported that the false-negative rate was higher when the screening doctors had less experience. However, false-negative results were observed in 19.6% of patients even when the endoscopy was performed by trained doctors certified by the Japan Gastroenterological Endo

Physicians of varying skill levels participate in endoscopic gastric cancer screening. Therefore, secondary review of endoscopic images by physicians who are board-certified by the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society is considered mandatory to compensate for any skill gaps among physicians and to standardize image in

The “Manual for Organized Gastric Endoscopic Screening” published by the Ja

The efficacy of radiographic screening in reducing mortality has been well verified. A recent study found that the efficacy of radiographic screening in reducing gastric cancer mortality rate is equivalent to that of endoscopic screening[18]. In contrast, another study found that radiographic screening did not show efficacy in reducing the gastric cancer mortality rate[19]. The Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society has recommended “a new radiography method” based on a double-contrast examination that uses high-density, low-viscosity barium sulfate[20]. Radiographic screening by this new method was reported to increase the detection rate of early cancer and reduce the requirement rate for detailed examinations when compared with the conventional screening method that uses medium-density barium sulfate[21,22].

The maximum follow-up period in our study was 5 years and 11 mo (i.e., 71 mo). Early cancer was reported to become advanced cancer over 44 mo and to lead to death over 75 mo[23]. The Tottori Cohort Study showed a significant difference in gastric cancer mortality rate from 3 years after the screening. Therefore, the present study may have had a different result if the follow-up period were longer.

In the present study, we were unable to evaluate the difference between the two screening methods based on the number of times participants had previously un

The analyses revealed no significant difference between the screening methods in any of the analysis sets, suggesting no noteworthy difference in the history of un

Stage IA gastric cancer detected by endoscopy was treated by ESD in 70% of the participants who were found to have a lesion. Intramucosal gastric cancer was more commonly detected by endoscopic screening. On the other hand, all cases of stage IA cancer detected by direct radiographic screening were treated by gastrectomy. The

Endoscopy is able to detect early gastric cancers more frequently than direct ra

Infection with Hp, current smoking, and salt and alcohol intake are known risk factors of gastric cancer. A previous study reported odds ratios of 2.56 for Hp infection, 1.61 for current smoking, 1.34 for salt intake, and 1.19 for alcohol intake[26]. We did not investigate the presence of Hp infection in participants in the 2006 Maebashi City gastric cancer screening because testing for Hp infection only began to be covered by health insurance in 2013. We also did not investigate smoking, salt intake, or drinking habits. Smoking and alcohol drinking are also risk factors for other cancers, but the present study found no significant difference between the two screening methods in terms of mortality rate from any cancer, which indicates that our comparison of the two screening methods had no risk factor-related bias.

The number of participants undergoing direct radiographic gastric cancer screening has decreased since its peak of 6.9 million or more in 2012[27]. Therefore, the in

The present study had some limitations. First, because of the low reporting rate to the Gunma Prefecture cancer registry in 2006, we were unable to determine whether the gastric cancer incidence rate in screening participants was similar across the two screening methods, even though we were able to collect information on cancer deaths from death certificates. Therefore, the incidences of gastric cancer may not be com

We used the data from the Maebashi City gastric cancer screening program in 2006 to compare the efficacy of direct radiography and endoscopy in reducing the gastric cancer mortality rate. In Maebashi City, a larger number of older adults participated in endoscopic gastric cancer screening than in direct radiographic screening. As a result, endoscopic screening detected more early gastric cancers than direct radiographic screening; however, the mortality rate showed no significant difference between the two screening methods. For future gastric cancer screening, physicians’ technical level gap across screening institutions should be corrected, and physicians’ interpretation accuracy in secondary review should also be further supported.

Gastric cancer is among the leading causes of cancer mortality worldwide, including in Japan. Initiatives have been implemented to lower the mortality rate of gastric cancer in Japan, including mass screening programs. In 2015, guidelines were revised to recommend endoscopy.

In Maebashi City, endoscopic gastric cancer screening was introduced in 2004, allowing eligible participants to choose between direct radiography and endoscopy. Comparing outcomes is essential to reduce gastric cancer mortality and ensure an effective and efficient screening program.

This study aimed to assess whether the mortality rate from gastric cancer decreased after the introduction of endoscopic screening in Maebashi City and compare gastric cancer mortality rates between screening methods.

A retrospective analysis of the Maebashi City Gastric Cancer Screening Program in 2006 was conducted. Participants aged 40 to 79 were screened by direct radiography (n = 11155) or endoscopy (n = 10747) and followed until March 31, 2012. Data was cross-referenced against the Gunma Prefecture cancer registry data. The detection rate of gastric cancer and gastric cancer mortality rate were compared between the two screening groups.

Gastric cancer detection rate for direct radiography was 0.20% and 0.48% for endo

No significant difference in gastric cancer mortality rate was found between direct radiographic screening and endoscopic screening. Screening programs should address gaps in endoscopists’ skill levels across screening institutions to ensure the quality of endoscopic examination. Finally, an efficient gastric cancer screening system should consider gastric cancer risk by combining endoscopic and radiographic screening.

Further research with a larger number of participants and high-quality cancer inci

The authors are deeply grateful to the doctors at medical institutions in Maebashi City for performing gastric cancer screening and secondary reading, as well as the staff members of the Maebashi Medical Association office for collecting data on gastric cancer screening.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Li BF, Li K, Sun QL, Yang Y S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yuan YY

| 1. | Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration, Fitzmaurice C, Abate D, Abbasi N, Abbastabar H, Abd-Allah F, Abdel-Rahman O, Abdelalim A, Abdoli A, Abdollahpour I, Abdulle ASM, Abebe ND, Abraha HN, Abu-Raddad LJ, Abualhasan A, Adedeji IA, Advani SM, Afarideh M, Afshari M, Aghaali M, Agius D, Agrawal S, Ahmadi A, Ahmadian E, Ahmadpour E, Ahmed MB, Akbari ME, Akinyemiju T, Al-Aly Z, AlAbdulKader AM, Alahdab F, Alam T, Alamene GM, Alemnew BTT, Alene KA, Alinia C, Alipour V, Aljunid SM, Bakeshei FA, Almadi MAH, Almasi-Hashiani A, Alsharif U, Alsowaidi S, Alvis-Guzman N, Amini E, Amini S, Amoako YA, Anbari Z, Anber NH, Andrei CL, Anjomshoa M, Ansari F, Ansariadi A, Appiah SCY, Arab-Zozani M, Arabloo J, Arefi Z, Aremu O, Areri HA, Artaman A, Asayesh H, Asfaw ET, Ashagre AF, Assadi R, Ataeinia B, Atalay HT, Ataro Z, Atique S, Ausloos M, Avila-Burgos L, Avokpaho EFGA, Awasthi A, Awoke N, Ayala Quintanilla BP, Ayanore MA, Ayele HT, Babaee E, Bacha U, Badawi A, Bagherzadeh M, Bagli E, Balakrishnan S, Balouchi A, Bärnighausen TW, Battista RJ, Behzadifar M, Bekele BB, Belay YB, Belayneh YM, Berfield KKS, Berhane A, Bernabe E, Beuran M, Bhakta N, Bhattacharyya K, Biadgo B, Bijani A, Bin Sayeed MS, Birungi C, Bisignano C, Bitew H, Bjørge T, Bleyer A, Bogale KA, Bojia HA, Borzì AM, Bosetti C, Bou-Orm IR, Brenner H, Brewer JD, Briko AN, Briko NI, Bustamante-Teixeira MT, Butt ZA, Carreras G, Carrero JJ, Carvalho F, Castro C, Castro F, Catalá-López F, Cerin E, Chaiah Y, Chanie WF, Chattu VK, Chaturvedi P, Chauhan NS, Chehrazi M, Chiang PP, Chichiabellu TY, Chido-Amajuoyi OG, Chimed-Ochir O, Choi JJ, Christopher DJ, Chu DT, Constantin MM, Costa VM, Crocetti E, Crowe CS, Curado MP, Dahlawi SMA, Damiani G, Darwish AH, Daryani A, das Neves J, Demeke FM, Demis AB, Demissie BW, Demoz GT, Denova-Gutiérrez E, Derakhshani A, Deribe KS, Desai R, Desalegn BB, Desta M, Dey S, Dharmaratne SD, Dhimal M, Diaz D, Dinberu MTT, Djalalinia S, Doku DT, Drake TM, Dubey M, Dubljanin E, Duken EE, Ebrahimi H, Effiong A, Eftekhari A, El Sayed I, Zaki MES, El-Jaafary SI, El-Khatib Z, Elemineh DA, Elkout H, Ellenbogen RG, Elsharkawy A, Emamian MH, Endalew DA, Endries AY, Eshrati B, Fadhil I, Fallah Omrani V, Faramarzi M, Farhangi MA, Farioli A, Farzadfar F, Fentahun N, Fernandes E, Feyissa GT, Filip I, Fischer F, Fisher JL, Force LM, Foroutan M, Freitas M, Fukumoto T, Futran ND, Gallus S, Gankpe FG, Gayesa RT, Gebrehiwot TT, Gebremeskel GG, Gedefaw GA, Gelaw BK, Geta B, Getachew S, Gezae KE, Ghafourifard M, Ghajar A, Ghashghaee A, Gholamian A, Gill PS, Ginindza TTG, Girmay A, Gizaw M, Gomez RS, Gopalani SV, Gorini G, Goulart BNG, Grada A, Ribeiro Guerra M, Guimaraes ALS, Gupta PC, Gupta R, Hadkhale K, Haj-Mirzaian A, Hamadeh RR, Hamidi S, Hanfore LK, Haro JM, Hasankhani M, Hasanzadeh A, Hassen HY, Hay RJ, Hay SI, Henok A, Henry NJ, Herteliu C, Hidru HD, Hoang CL, Hole MK, Hoogar P, Horita N, Hosgood HD, Hosseini M, Hosseinzadeh M, Hostiuc M, Hostiuc S, Househ M, Hussen MM, Ileanu B, Ilic MD, Innos K, Irvani SSN, Iseh KR, Islam SMS, Islami F, Jafari Balalami N, Jafarinia M, Jahangiry L, Jahani MA, Jahanmehr N, Jakovljevic M, James SL, Javanbakht M, Jayaraman S, Jee SH, Jenabi E, Jha RP, Jonas JB, Jonnagaddala J, Joo T, Jungari SB, Jürisson M, Kabir A, Kamangar F, Karch A, Karimi N, Karimian A, Kasaeian A, Kasahun GG, Kassa B, Kassa TD, Kassaw MW, Kaul A, Keiyoro PN, Kelbore AG, Kerbo AA, Khader YS, Khalilarjmandi M, Khan EA, Khan G, Khang YH, Khatab K, Khater A, Khayamzadeh M, Khazaee-Pool M, Khazaei S, Khoja AT, Khosravi MH, Khubchandani J, Kianipour N, Kim D, Kim YJ, Kisa A, Kisa S, Kissimova-Skarbek K, Komaki H, Koyanagi A, Krohn KJ, Bicer BK, Kugbey N, Kumar V, Kuupiel D, La Vecchia C, Lad DP, Lake EA, Lakew AM, Lal DK, Lami FH, Lan Q, Lasrado S, Lauriola P, Lazarus JV, Leigh J, Leshargie CT, Liao Y, Limenih MA, Listl S, Lopez AD, Lopukhov PD, Lunevicius R, Madadin M, Magdeldin S, El Razek HMA, Majeed A, Maleki A, Malekzadeh R, Manafi A, Manafi N, Manamo WA, Mansourian M, Mansournia MA, Mantovani LG, Maroufizadeh S, Martini SMS, Mashamba-Thompson TP, Massenburg BB, Maswabi MT, Mathur MR, McAlinden C, McKee M, Meheretu HAA, Mehrotra R, Mehta V, Meier T, Melaku YA, Meles GG, Meles HG, Melese A, Melku M, Memiah PTN, Mendoza W, Menezes RG, Merat S, Meretoja TJ, Mestrovic T, Miazgowski B, Miazgowski T, Mihretie KMM, Miller TR, Mills EJ, Mir SM, Mirzaei H, Mirzaei HR, Mishra R, Moazen B, Mohammad DK, Mohammad KA, Mohammad Y, Darwesh AM, Mohammadbeigi A, Mohammadi H, Mohammadi M, Mohammadian M, Mohammadian-Hafshejani A, Mohammadoo-Khorasani M, Mohammadpourhodki R, Mohammed AS, Mohammed JA, Mohammed S, Mohebi F, Mokdad AH, Monasta L, Moodley Y, Moosazadeh M, Moossavi M, Moradi G, Moradi-Joo M, Moradi-Lakeh M, Moradpour F, Morawska L, Morgado-da-Costa J, Morisaki N, Morrison SD, Mosapour A, Mousavi SM, Muche AA, Muhammed OSS, Musa J, Nabhan AF, Naderi M, Nagarajan AJ, Nagel G, Nahvijou A, Naik G, Najafi F, Naldi L, Nam HS, Nasiri N, Nazari J, Negoi I, Neupane S, Newcomb PA, Nggada HA, Ngunjiri JW, Nguyen CT, Nikniaz L, Ningrum DNA, Nirayo YL, Nixon MR, Nnaji CA, Nojomi M, Nosratnejad S, Shiadeh MN, Obsa MS, Ofori-Asenso R, Ogbo FA, Oh IH, Olagunju AT, Olagunju TO, Oluwasanu MM, Omonisi AE, Onwujekwe OE, Oommen AM, Oren E, Ortega-Altamirano DDV, Ota E, Otstavnov SS, Owolabi MO, P A M, Padubidri JR, Pakhale S, Pakpour AH, Pana A, Park EK, Parsian H, Pashaei T, Patel S, Patil ST, Pennini A, Pereira DM, Piccinelli C, Pillay JD, Pirestani M, Pishgar F, Postma MJ, Pourjafar H, Pourmalek F, Pourshams A, Prakash S, Prasad N, Qorbani M, Rabiee M, Rabiee N, Radfar A, Rafiei A, Rahim F, Rahimi M, Rahman MA, Rajati F, Rana SM, Raoofi S, Rath GK, Rawaf DL, Rawaf S, Reiner RC, Renzaho AMN, Rezaei N, Rezapour A, Ribeiro AI, Ribeiro D, Ronfani L, Roro EM, Roshandel G, Rostami A, Saad RS, Sabbagh P, Sabour S, Saddik B, Safiri S, Sahebkar A, Salahshoor MR, Salehi F, Salem H, Salem MR, Salimzadeh H, Salomon JA, Samy AM, Sanabria J, Santric Milicevic MM, Sartorius B, Sarveazad A, Sathian B, Satpathy M, Savic M, Sawhney M, Sayyah M, Schneider IJC, Schöttker B, Sekerija M, Sepanlou SG, Sepehrimanesh M, Seyedmousavi S, Shaahmadi F, Shabaninejad H, Shahbaz M, Shaikh MA, Shamshirian A, Shamsizadeh M, Sharafi H, Sharafi Z, Sharif M, Sharifi A, Sharifi H, Sharma R, Sheikh A, Shirkoohi R, Shukla SR, Si S, Siabani S, Silva DAS, Silveira DGA, Singh A, Singh JA, Sisay S, Sitas F, Sobngwi E, Soofi M, Soriano JB, Stathopoulou V, Sufiyan MB, Tabarés-Seisdedos R, Tabuchi T, Takahashi K, Tamtaji OR, Tarawneh MR, Tassew SG, Taymoori P, Tehrani-Banihashemi A, Temsah MH, Temsah O, Tesfay BE, Tesfay FH, Teshale MY, Tessema GA, Thapa S, Tlaye KG, Topor-Madry R, Tovani-Palone MR, Traini E, Tran BX, Tran KB, Tsadik AG, Ullah I, Uthman OA, Vacante M, Vaezi M, Varona Pérez P, Veisani Y, Vidale S, Violante FS, Vlassov V, Vollset SE, Vos T, Vosoughi K, Vu GT, Vujcic IS, Wabinga H, Wachamo TM, Wagnew FS, Waheed Y, Weldegebreal F, Weldesamuel GT, Wijeratne T, Wondafrash DZ, Wonde TE, Wondmieneh AB, Workie HM, Yadav R, Yadegar A, Yadollahpour A, Yaseri M, Yazdi-Feyzabadi V, Yeshaneh A, Yimam MA, Yimer EM, Yisma E, Yonemoto N, Younis MZ, Yousefi B, Yousefifard M, Yu C, Zabeh E, Zadnik V, Moghadam TZ, Zaidi Z, Zamani M, Zandian H, Zangeneh A, Zaki L, Zendehdel K, Zenebe ZM, Zewale TA, Ziapour A, Zodpey S, Murray CJL. Global, Regional, and National Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Years of Life Lost, Years Lived With Disability, and Disability-Adjusted Life-Years for 29 Cancer Groups, 1990 to 2017: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:1749-1768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1723] [Cited by in RCA: 1750] [Article Influence: 291.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | National Cancer Center. Cancer Information Services. [cited 4 December 2020]. Available from: https://ganjoho.jp/reg_stat/statistics/stat/summary.html. |

| 3. | Hamashima C; Systematic Review Group and Guideline Development Group for Gastric Cancer Screening Guidelines. Update version of the Japanese Guidelines for Gastric Cancer Screening. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2018;48:673-683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 281] [Cited by in RCA: 268] [Article Influence: 38.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hagiwara H, Yamashita Y, Yagi T, Koitabashi T, Ishida M, Sekiguchi T, Imai T. Present situation and problems in individual gastric cancer screening conducted by endoscopy at multiple facilities. J Gastrointestinal Cancer Screen. 2008;46:472-481. |

| 5. | Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. [cited 14 December 2020]. Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/Life/Life06/01.html. |

| 6. | Neuberger J, Altman DG, Christensen E, Tygstrup N, Williams R. Use of a prognostic index in evaluation of liver transplantation for primary biliary cirrhosis. Transplantation. 1986;41:713-716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Nieto FJ, Coresh J. Adjusting survival curves for confounders: a review and a new method. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;143:1059-1068. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software 'EZR' for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:452-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9275] [Cited by in RCA: 13272] [Article Influence: 1106.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma. 13th edition. Tokyo: KANEHARA&Co., Ltd, 1999: 39. |

| 10. | Hamashima C, Shabana M, Okada K, Okamoto M, Osaki Y. Mortality reduction from gastric cancer by endoscopic and radiographic screening. Cancer Sci. 2015;106:1744-1749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | The Japanese Society of Gastrointestinal Cancer Screening. Quality Assurance of Endoscopic Screening for Gastric Cancer in Japanese Communities. 2017. [cited 14 December 2020]. Available from: https://www.jsgcs.or.jp. |

| 12. | e-Stat. Official Statistics of Japan. [Cited 14 December 2020]. Available from: https://www.e-stat.go.jp/dbview?sid=0003026748,003026801,0003289757,0003289801. |

| 13. | Shimodate Y, Mizuno M, Doi A, Nishimura N, Mouri H, Matsueda K, Yamamoto H. Gastric superficial neoplasia: high miss rate but slow progression. Endosc Int Open. 2017;5:E722-E726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hosokawa O, Hattori M, Takeda T, Watanabe K, Fujita M. Accuracy of endoscopy in detecting gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol Mass Sur. 2004;42:33-39. |

| 15. | Ogoshi K, Narisawa R, Kato T, Saito Y, Funakoshi K, Kinameri K. Evaluation of endoscopic screening for gastric cancer in Niigata City: the reduction of the mortality rate. J Gastrointestinal Cancer Screen. 2009;47:531-541. |

| 16. | Ohno K, Takabatake I, Nishimura G, Ueno T, Kaji K, Hashiba A, Takeda Y. Examination of the Kanazawa-shi method (the third reading shadow) in multicenter endoscopic for gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2014;52:715-722. |

| 17. | Hagiwara H, Yamashita Y, Yagi T, Koitabashi T, Moki F. Current status of use of transnasal endoscopy in personal health checkup and its accuracy in screening gastric cancers at multiple institutions. J Gastrointestinal Cancer Screen. 2009;47:683-692. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 18. | Matsumoto S, Ishikawa S, Yoshida Y. Reduction of gastric cancer mortality by endoscopic and radiographic screening in an isolated island: A retrospective cohort study. Aust J Rural Health. 2013;21:319-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hamashima C, Ogoshi K, Okamoto M, Shabana M, Kishimoto T, Fukao A. A community-based, case-control study evaluating mortality reduction from gastric cancer by endoscopic screening in Japan. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | The Japanese Society of Gastrointestinal Cancer Screening. New Guidelines of Radiography for Gastric Cancer Screening. 2011. [cited 14 December 2020]. Available from: https://www.jsgcs.or.jp. |

| 21. | Shimizu K, Kunihiro K, Onoda H, Tanabe M, Matsukuma M, Matsunaga N. Evaluation of gastric mass screening during the shift to a new standard method focused on the detection of early gastric cancers. Nihon Shoukaki Gan Kenshin Gakkai zasshi. 2009;47:35-42. |

| 22. | Murakami H, Tuchigame T, Murata Y, Awazu Y, Maeda M, Ogata I, Nishi J. Evaluation of mass screening for stomach cancers. Nihon Shoukaki Gan Kenshin Gakkai zasshi. 2007;45:399-404. |

| 23. | Tsukuma H, Oshima A, Narahara H, Morii T. Natural history of early gastric cancer: a non-concurrent, long term, follow up study. Gut. 2000;47:618-621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hagiwara H, Moki F, Sekiguchi T, Yamashita Y, Yagi T, Koitabashi T. Effectiveness of gastroendoscopic examination in individual screening for stomach cancer. Nihon Shoukaki Gan Kenshin Gakkai zasshi. 2015;53:376-382. |

| 25. | Hamashima C, Sobue T, Muramatsu Y, Saito H, Moriyama N, Kakizoe T. Comparison of observed and expected numbers of detected cancers in the research center for cancer prevention and screening program. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2006;36:301-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Poorolajal J, Moradi L, Mohammadi Y, Cheraghi Z, Gohari-Ensaf F. Risk factors for stomach cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol Health. 2020;42:e2020004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 33.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | The Japanese Society of Gastrointestinal Cancer Screening. Annual Report of Gastrointestinal Cancer Screening 2014. [cited 14 December 2020]. Available from: https://www.jsgcs.or.jp. |