Published online Aug 7, 2021. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i29.4929

Peer-review started: February 25, 2021

First decision: April 18, 2021

Revised: April 29, 2021

Accepted: July 13, 2021

Article in press: July 13, 2021

Published online: August 7, 2021

Processing time: 159 Days and 17.7 Hours

Autoimmune enteropathy (AIE) and primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) are both immune-mediated diseases. AIE or PBC complicated with ulcerative colitis (UC) are rare. There are no cases of AIE and PBC diagnosed after proctocolectomy for UC reported before, and the pathogenesis of these comorbidities has not been revealed.

A middle-aged woman diagnosed with UC underwent subtotal colectomy and ileostomy due to the steroid-resistant refractory disease, and a restorative proctectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis and proximal neoileostomy was postponed due to active residual rectal inflammation in January 2016. A few months after the neoileostomy, she began to suffer from recurrent episodes of watery diarrhea. She was diagnosed with postcolectomy enteritis and stoma closure acquired a good therapeutic effect. However, her symptoms of diarrhea relapsed in 2019, with different histological features of endoscopic biopsies compared with 2016, which showed apoptotic bodies, a lack of goblet and Paneth cells, and villous blunting. A diagnosis of AIE was established, and the patient’s stool volume decreased dramatically with the treatment of methylprednisolone 60 mg/d for 1 wk and tacrolimus 3 mg/d for 4 d. Meanwhile, her constantly evaluated cholestatic enzymes and high titers of antimitochondrial antibodies indicated the diagnosis of PBC, and treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid (16 mg/kg per day) achieved satisfactory results.

Some immune-mediated diseases may be promoted by operation due to microbial alterations in UC patients. Continuous follow-up is essential for UC patients with postoperative complications.

Core Tip: This is the first case report of autoimmune enteropathy and primary biliary cholangitis complicated with ulcerative colitis, and the female patient in this case suffered from a tortuous process of diagnosis and treatment. It is speculated that a microbial shift and subsequent immune response are involved in the pathogenesis of these comorbidities, and surgery may facilitate the progression of coexisting diseases. Understanding the progression of these diseases may help with their early recognition and treatment.

- Citation: Zhou QY, Zhou WX, Sun XY, Wu B, Zheng WY, Li Y, Qian JM. Autoimmune enteropathy and primary biliary cholangitis after proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis: A case report and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol 2021; 27(29): 4929-4938

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v27/i29/4929.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v27.i29.4929

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) affecting the colon and rectum. Dysregulated immune responses to microbial changes and epithelial barrier defects are reported to contribute to the pathogenesis of UC. Small bowel involvement in UC is usually characterized by backwash ileitis or pouchitis[1]. Diffuse and severe enteritis occurring after colectomy for UC, which is referred to as postcolectomy enteritis, has been sporadically reported in the literature[2-5]. The pathogenesis and prognosis remain obscure. A case of postcolectomy enteritis previously reported by our team[3] recently presented recurrent large-volume watery diarrhea and typical pathological features of autoimmune enteropathy (AIE) along with high titers of antimitochondrial antibodies (AMAs) and increased cholestatic enzymes. The association of UC with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) has been commonly reported[6], whereas UC with primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) has been rarely reported, and the underlying pathogenesis may be different. In this report, we present a rare case of progressive AIE and PBC after colectomy for UC and propose a hypothesis to explain the potential associations of these coexisting diseases.

A 54-year-old woman presented to the Emergency Department complaining of large-volume watery diarrhea.

The patient was diagnosed with moderate to severe extensive UC at the age of 49 in December 2014. Subtotal colectomy and ileostomy were performed in February 2015 due to steroid-resistant refractory disease. The UC diagnosis was pathologically confirmed in resected specimens without ileitis. Her general condition improved greatly after ileostomy. A restorative proctectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis and proximal neoileostomy was postponed until January 2016 due to active residual rectal inflammation. Within 3 mo after the neoileostomy, the patient noticed that watery stool from the stoma gradually increased up to 3-4 L per 24 h. She was admitted to our hospital for hypovolemic shock, electrolyte and acid-base distur

The patient had a past medical history of poliomyelitis.

Unremarkable.

The patient was in serious weakness with cold limbs when admitted. Her vital signs were as follows: Temperature was 36.1 °C, heart rate was 109 bpm, respiratory rate was 20 breaths/min, blood pressure was 87/66 mmHg, and oxygen saturation in room air was 99%. The clinical physical examination revealed hyperactive bowel sounds 7-8 times/min, and no abdominal tenderness during palpation.

Blood analysis revealed hemoglobin 181 g/L, platelets 274 × 109/L, white blood cells 11.63 × 109/L, neutrophils 68.7%, and lymphocytes 20.6%. Blood biochemical values were abnormal, with alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 22 U/L, total bilirubin 22.4 μmol/L, albumin 48 g/L, creatinine 206 μmol/L, urea 10.15 mmol/L, serum potassium 5.1 mmol/L, and serum sodium 128 mmol/L. Her arterial blood gas parameters were: pH 7.55, partial pressure CO2 23 mmHg, partial pressure O2 113 mmHg, bicarbonate 20.1 mmol/L, base excess 0.3 mmol/L, and lactic acid 3.1 mmol/L. Serum C-reactive protein was increased at 24.55 mg/L (normal range ≤ 8 mg/L) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate at 34 mm/h. Routine stool test showed 6-8 white blood cells per high power field and occult blood was noted. Stool pathogen screening was negative except for Candida albicans in stool culture.

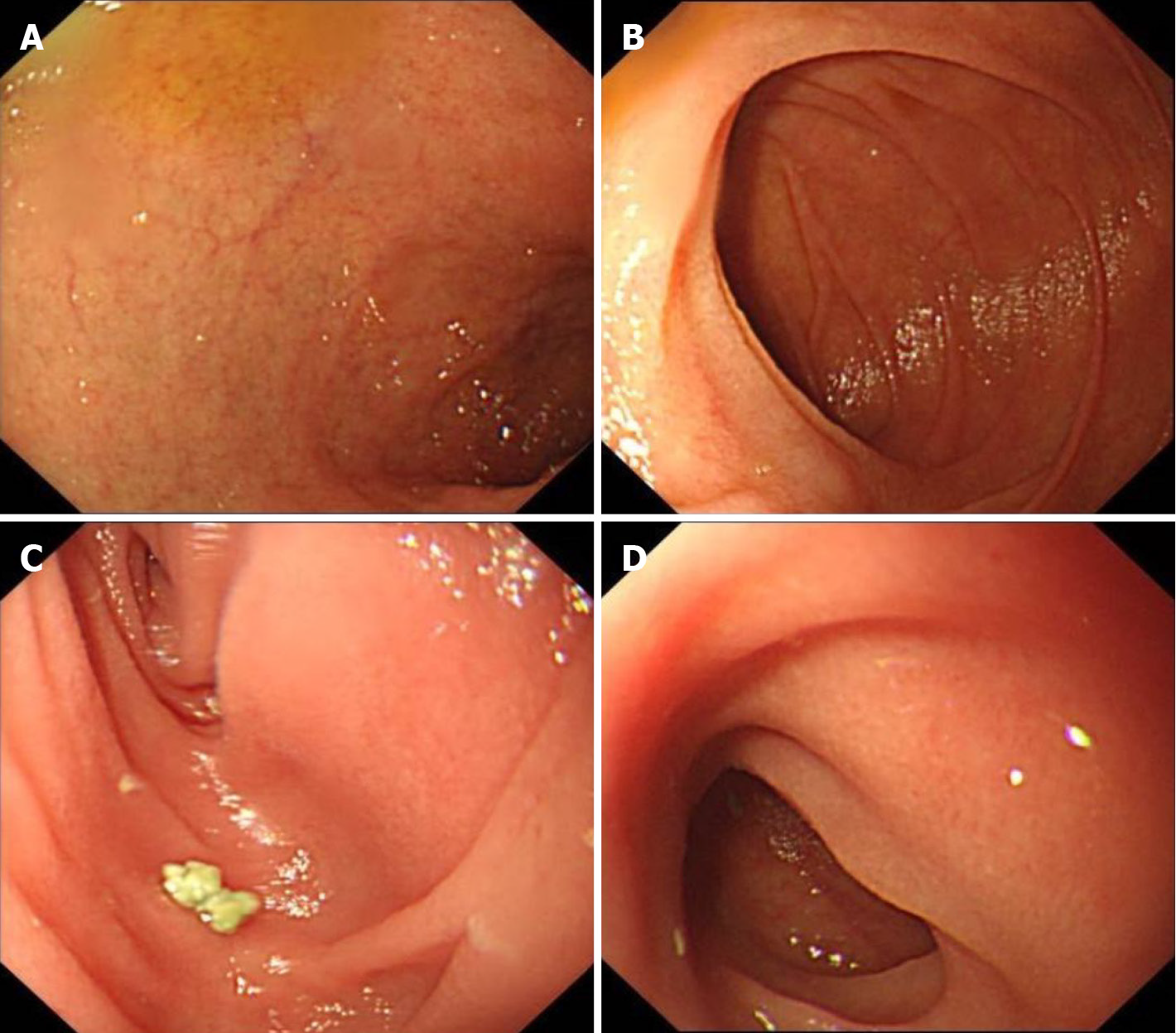

No significantly abnormal signs were found on abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT). Endoscopy revealed an intact mucosa with diffuse villous atrophy in the duodenum, ileum, and ileal pouch (Figure 3). Histopathological findings of biopsies showed apoptotic bodies, a lack of goblet and Paneth cells, and villous blunting, which were not prominent in 2016 (Figure 4).

The principal clinical manifestation of AIE was refractory diarrhea with no response to dietary modification. Characteristic histological features included villous blunting or atrophy, apoptotic bodies, and lymphocytic infiltration in the crypt epithelium. The absence of goblet and Paneth cells also supported a diagnosis of AIE[7]. Given the typical clinical and histological features strongly supporting AIE and no evidence for other diseases causing villous atrophy and mucosal inflammation in this case, a diagnosis of AIE was established. As the sensitivity and specificity of AMA-M2 for PBC diagnosis are both 90%-95%[8], positive AMA-M2 made the diagnosis of PBC definitive. Despite having no signs of extrahepatic biliary obstruction on magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, small duct PSC could not be excluded completely due to a lack of histologic evidence. A previous case report showed the overlap of PBC and small duct PSC[9], indicating that typical onion-skin lesions in biliary ducts, with concentric fibrosis, can be seen in small duct PSC with MRI negativity. As a result, liver biopsy is needed to confirm the diagnosis of PBC, if possible.

Supportive treatments with intravenous infusions, vasoactive drugs, and regulating electrolyte disturbances were performed timely to maintain the stable vital signs. Methylprednisolone 60 mg/d was given intravenously for 1 wk, and tacrolimus 3 mg/d (target blood concentration 3-10 ng/mL) was given to maintain the treatment response when steroids were tapered. As for PBC, ursodeoxycholic acid 16mg/kg per day was prescribed.

The patient’s vital signs became stable under sufficient supportive treatments. After treatment with methylprednisolone 60 mg/d for 1 wk, her stool volume gradually decreased to less than 1.5 L/d. After taking tacrolimus for 4 d, the stool volume decreased to approximately 0.5 L/d and solid components could be seen in the liquid stool. The levels of ALT, aspartate aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, gamma-glutamyl transferase, and serum total bilirubin decreased gradually compared with the peak levels (109 U/L to 67 U/L, 87 U/L to 30 U/L, 404 U/L to 87 U/L, 659 U/L to 137 U/L, and 161.8 μmol/L to 20.3 μmol/L, respectively).

We searched the PubMed and Embase databases for case reports published in English or with an English abstract before June 22, 2020, with the keywords “ulcerative colitis”, “autoimmune enteropathy”, and “primary biliary cholangitis” (or “primary biliary cirrhosis”). There is only one case of AIE in a UC patient[10] and 20 cases of PBC in UC patients[11-13]. Therefore, our patient is the first case of UC complicated with AIE and PBC after colectomy.

This patient presented similar watery diarrhea in 2019 as in 2016, and the pathological features of the small intestine progressed. The diagnosis of postcolectomy enteritis was based on clinical manifestations of diffuse, superficial mucosal inflammation of the small bowel after colectomy in a UC patient, and the underlying pathogenesis remains unknown. In this case, with recurrent enteritis, typical pathological features of AIE were noticed during relapse, and we speculate that this progression was mediated by the same pathogenic mechanisms. We review the 23 previous cases of postcolectomy enteritis in UC (from an English database, including two cases in Japanese with English abstracts)[2,3] and summarize the histological characteristics of small intestinal biopsies[2,4,5,14-25] (Table 1). A large proportion of these cases exhibited typical features of UC, with inflammatory infiltration of the lamina propria by lymphocytes, plasma cells, monocytes, or a few neutrophils found in 19 cases and cryptitis or crypt abscess in 9 cases. Typical features of AIE, including apoptotic bodies and decreased goblet cells (3 and 1 cases, respectively), were also reported in these patients[4,5]. Above all, we propose a hypothesis that these pathological features are present at different stages in a dysregulated immune condition triggered by a microbial shift after colectomy. It is possible that three cases of postcolectomy enteritis with features of AIE (apoptotic bodies)[4,5] may progress to AIE during follow-up because these cases presented with severe clinical manifestations similar to our patient, with one of them even worse (dying of multiorgan failure).

| Ref. | Age1/sex | Extent of UC | Onset of enteritis2 | Extent of enteritis | Histological characteristics of biopsies |

| Corporaal et al[2] | 23/M | Extended left sided | 2 wk after colectomy | J, I | Marked apoptosis of epithelial cells, lamina propria with lymphoplasma cellular infiltrate with eosinophilic and neutrophilic granulocytes |

| Corporaal et al[2] | 61/M | Pancolitis | 1 mo after colectomy | S, D, J, I | Diffuse active chronic inflammatory infiltrate with (sub) total villous atrophy (D), an increase in the apoptosis of crypt epithelial cells (I), and dense active chronic inflammation (S) |

| Gooding et al[14] | 52/M | Pancolitis | 116 d after colectomy | D, I | Infiltration of the lamina propria by lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils; cryptitis and small numbers of neutrophils within the upper-crypt lamina and on the surface (D); shortening and irregularity of villi; mild, diffuse, chronic inflammatory cell infiltration; and mild activity with cryptitis (I) |

| Ikeuchi et al[15] | 29/F | Left sided | 6 yr after colectomy | S, D, I | Severe infiltration of inflammatory cells in the mucosa (I, S) and crypt abscess in the mucous glandules (S), dense, acute, and chronic inflammatory infiltrates accompanied with cryptitis (D) |

| Kawai et al[16] | Young (unknown)/M | Pancolitis | 12 yr after colectomy | D | Lymphoplasmacytic infiltration of the duodenal mucosa without granuloma formation |

| Kawai et al[16] | Unknown/M | Unknown | 2 yr after colectomy | I | Unknown |

| Rubenstein et al[17] | 38/M | Pancolitis | Immediately after colectomy | D, J, I | Diffuse mucosal inflammation with the distortion of the crypt architecture and plasmacytosis |

| Nakayama et al[18] | 41/M | Pancolitis | 3.5 yr after colectomy | D, I | Inflammatory infiltration by neutrophils, eosinophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells |

| Terashima et al[19] | 30/M | Left sided | 7 mo after colectomy, immediately after closure of ileostoma | D | Severe lymphoplasmacytic infiltration withcryptitis |

| Valdez et al[20] | 5/F | Pancolitis | 17 mo after colectomy | D | Diffuse mucosal inflammation, cryptitis, and architectural distortion |

| Valdez et al[20] | 17/F | Pancolitis | 9 mo after colectomy | D, I | Diffuse mucosal inflammation, cryptitis, and architectural distortion |

| Valdez et al[20] | 58/F | Pancolitis | 6 mo after colectomy | D, J | Typical microscopic features of UC (no other details) |

| Valdez et al[20] | 17/M | Pancolitis | 8 d after colectomy | D, I | UC-like active, diffuse duodenitis and ileitis (no other details) |

| Annese et al[21] | 37/M | Pancolitis | 1 mo after colectomy | D, J, I | Architectural disarray and dense inflammatory infiltrate extending beyond the muscularis mucosae, mainly comprised of plasma cells and lymphocytes (D, J). Distorted villi and a heavily inflamed lamina propria with mononuclear cell inflammatory infiltrate (I) |

| Feuerstein et al[4] | 56/F | Left sided | 26 d after colectomy | D, J, I | Severe, active enteritis with ulceration and prominent epithelial cell, apoptotic debris |

| Nakajima et al[5] | 25/F | Pancolitis | Immediately after colectomy | D, J, I | Infiltration of inflammatory cells in the mucosa and decreased goblet cells |

| Hoentjen et al[22] | 23/M | Pancolitis | 3 mo after colectomy | S, D, I | Severe active inflammation with significant neutrophil infiltration in the epithelium and lamina propria |

| Hoentjen et al[22] | 24/F | Pancolitis | 4 mo after colectomy | S, D, I | Mixed cell infiltrates in the lamina propria, including a prominent component of plasma cells and clusters of neutrophils, negative for crypt cell apoptosis and decreased goblet cells |

| Hoentjen et al[22] | 27/M | Pancolitis | 25 yr after colectomy | S, D, I | Active inflammation with prominent eosinophils in the lamina propria (S, D) and remarkable architectural distortion (I) |

| Hoentjen et al[22] | 57/M | Pancolitis | 27 mo after colectomy | S, D, I | Diffuse and active Helicobacter pylori-negative gastritis, duodenitis and ileitis (no other details) |

| Uchino et al[23] | 19/M | Pancolitis | 12 d after colectomy | S, D, I | Neutrophil infiltration and crypt abscess |

| Rush et al[24] | 43/F | Pancolitis | 3 mo after colectomy | S, D, J, I | Moderate to marked active chronic inflammation with cryptitis |

| Rosenfeld et al[25] | 47/F | Pancolitis | 4 mo after colectomy | D, J | Moderate to severe active inflammatory changes in the small bowel mucosa with cryptitis |

The nature of the relationship between PBC and UC is unexplained. Immune-pathogenic mechanisms may be implicated in the pathogenesis of UC complicated with autoimmune hepatobiliary disorders[26]. Lymphocytic infiltration of portal tracts and the presence of circulating antibodies that react with bile ducts[7,27] suggest that the two diseases share common immunological pathways. Our patient initially suffered from refractory and progressive disease after colectomy in 2016, which suggests that surgery may be a potential factor that promotes disease progression. A widely accepted hypothesis regarding the pathogenesis of IBD indicates that the mucosal immune system exhibits an aberrant response towards luminal antigens, including commensal bacteria[28,29]. Meanwhile, some researchers have proposed that molecular mimicry may be a potential pathogenic mechanism underlying immune-mediated biliary damage. Antibodies that bind to the mitochondrial E2 subunit of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC-E2) also cross-react with conserved bacterial proteins, including microbes found on mucosal surfaces and in the feces[26]. Such bacterial mimics of PDC-E2 were believed to trigger AMA-M2 formation in the early stage of PBC pathogenesis[29]. Another “leaky gut” hypothesis proposed to explain the disease process in PSC inspired us to investigate the pathogenesis of hepatobiliary disorders. The disruption of bowel permeability may lead to bacterial translocation and bile colonization and subsequently activate the inflammatory response and fibrosis in the liver by activating cholangiocytes[30]. A case report described a female patient with UC who developed PBC after proctocolectomy[31]. Whether the occurrence of AIE and PBC after proctocolectomy in this patient was accidental or predestined based on the genetic, microbial, and immune background is worthy of further investigation.

We have reported a patient with UC complicated with AIE and PBC and hypothesized the possible underlying pathogenesis. Although there is insufficient clear evidence of the mechanism, this case offers us a new explanation for the spectrum of immune-mediated diseases. Proctocolectomy may promote the progression of UC due to microbial alterations, leading to complications in other target organs. For UC patients with postoperative complications, continuous follow-up is essential for early recognition and comprehensive treatment.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cibor D, Itabashi M, Naswhan AJ S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Ungaro R, Mehandru S, Allen PB, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Colombel JF. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2017;389:1756-1770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2199] [Cited by in RCA: 2484] [Article Influence: 310.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Corporaal S, Karrenbeld A, van der Linde K, Voskuil JH, Kleibeuker JH, Dijkstra G. Diffuse enteritis after colectomy for ulcerative colitis: two case reports and review of the literature. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:710-715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Yang Y, Liu Y, Zheng W, Zhou W, Wu B, Sun X, Chen W, Guo T, Li X, Yang H, Qian J, Li Y. A literature review and case report of severe and refractory post-colectomy enteritis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019;19:61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Feuerstein JD, Shah S, Najarian R, Nagle D, Moss AC. A fatal case of diffuse enteritis after colectomy for ulcerative colitis: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1086-1089. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nakajima M, Nakashima H, Kiyohara K, Sakatoku M, Fujimori H, Terahata S, Nobata H. [Case with diffuse duodenitis and enteritis following total colectomy for ulcerative colitis]. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2008;105:382-390. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Fousekis FS, Theopistos VI, Katsanos KH, Tsianos EV, Christodoulou DK. Hepatobiliary Manifestations and Complications in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Review. Gastroenterology Res. 2018;11:83-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Umetsu SE, Brown I, Langner C, Lauwers GY. Autoimmune enteropathies. Virchows Arch. 2018;472:55-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Leuschner U. Primary biliary cirrhosis--presentation and diagnosis. Clin Liver Dis. 2003;7:741-758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Oliveira EM, Oliveira PM, Becker V, Dellavance A, Andrade LE, Lanzoni V, Silva AE, Ferraz ML. Overlapping of primary biliary cirrhosis and small duct primary sclerosing cholangitis: first case report. J Clin Med Res. 2012;4:429-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rodriguez NJ, Gupta N, Gibson J. Autoimmune Enteropathy in an Ulcerative Colitis Patient. ACG Case Rep J. 2018;5:e78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tada F, Abe M, Nunoi H, Azemoto N, Mashiba T, Furukawa S, Kumagi T, Murakami H, Ikeda Y, Matsuura B, Hiasa Y, Onji M. Ulcerative colitis complicated with primary biliary cirrhosis. Intern Med. 2011;50:2323-2327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Polychronopoulou E, Lygoura V, Gatselis NK, Dalekos GN. Increased cholestatic enzymes in two patients with long-term history of ulcerative colitis: consider primary biliary cholangitis not always primary sclerosing cholangitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Liberal R, Gaspar R, Lopes S, Macedo G. Primary biliary cholangitis in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2020;44:e5-e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gooding IR, Springall R, Talbot IC, Silk DB. Idiopathic small-intestinal inflammation after colectomy for ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:707-709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ikeuchi H, Hori K, Nishigami T, Nakano H, Uchino M, Nakamura M, Kaibe N, Noda M, Yanagi H, Yamamura T. Diffuse gastroduodenitis and pouchitis associated with ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:5913-5915. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kawai K, Watanabe T, Nakayama H, Roberts-Thomson I, Nagawa H. Images of interest. Gastrointestinal: small bowel inflammation and ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:1791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Rubenstein J, Sherif A, Appelman H, Chey WD. Ulcerative colitis associated enteritis: is ulcerative colitis always confined to the colon? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:46-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Nakayama S, Matsuoka M, Yoshida Y, Hayakawa K, Fukuchi S, Matsukuma S. [A case of pouchitis, duodenitis and pancreatitis showing diffuse irregular narrowing of main pancreatic duct after total colectomy for ulcerative colitis]. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2004;101:389-396. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Terashima S, Hoshino Y, Kanzaki N, Kogure M, Gotoh M. Ulcerative duodenitis accompanying ulcerative colitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;32:172-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Valdez R, Appelman HD, Bronner MP, Greenson JK. Diffuse duodenitis associated with ulcerative colitis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1407-1413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Annese V, Caruso N, Bisceglia M, Lombardi G, Clemente R, Modola G, Tardio B, Villani MR, Andriulli A. Fatal ulcerative panenteritis following colectomy in a patient with ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:1189-1195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hoentjen F, Hanauer SB, Hart J, Rubin DT. Long-term treatment of patients with a history of ulcerative colitis who develop gastritis and pan-enteritis after colectomy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:52-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Uchino M, Ikeuchi H, Bando T, Matsuoka H, Hirata A, Takahashi Y, Takesue Y, Inoue S, Tomita N. Diffuse gastroduodenitis and enteritis associated with ulcerative colitis and concomitant cytomegalovirus reactivation after total colectomy: report of a case. Surg Today. 2013;43:321-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Rush B, Berger L, Rosenfeld G, Bressler B. Tacrolimus Therapy for Ulcerative Colitis-Associated Post-Colectomy Enteritis. ACG Case Rep J. 2014;2:33-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Rosenfeld GA, Freeman H, Brown M, Steinbrecher UP. Severe and extensive enteritis following colectomy for ulcerative colitis. Can J Gastroenterol. 2012;26:866-867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Mattner J. Impact of Microbes on the Pathogenesis of Primary Biliary Cirrhosis (PBC) and Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis (PSC). Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kaplan MM, Gershwin ME. Primary biliary cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1261-1273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 965] [Cited by in RCA: 922] [Article Influence: 46.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Podolsky DK. Inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:417-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2693] [Cited by in RCA: 2747] [Article Influence: 119.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 29. | Shimoda S, Nakamura M, Ishibashi H, Kawano A, Kamihira T, Sakamoto N, Matsushita S, Tanaka A, Worman HJ, Gershwin ME, Harada M. Molecular mimicry of mitochondrial and nuclear autoantigens in primary biliary cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1915-1925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Pontecorvi V, Carbone M, Invernizzi P. The "gut microbiota" hypothesis in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4:512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ohge H, Takesue Y, Yokoyama T, Hiyama E, Murakami Y, Imamura Y, Shimamoto F, Matsuura Y. Progression of primary biliary cirrhosis after proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:870-872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |