Published online May 14, 2021. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i18.2193

Peer-review started: January 27, 2021

First decision: March 7, 2021

Revised: March 21, 2021

Accepted: April 20, 2021

Article in press: April 20, 2021

Published online: May 14, 2021

Processing time: 102 Days and 19.7 Hours

Although several methods of totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy (TLTG) have been reported. The best anastomosis technique for LTG has not been established.

To investigate the effectiveness and surgical outcomes of TLTG using the modified overlap method compared with open total gastrectomy (OTG) using the circular stapled method.

We performed 151 and 131 surgeries using TLTG with the modified overlap method and OTG for gastric cancer between March 2012 and December 2018. Surgical and oncological outcomes were compared between groups using propensity score matching. In addition, we analyzed the risk factors associated with postoperative complications.

Patients who underwent TLTG were discharged earlier than those who underwent OTG [TLTG (9.62 ± 5.32) vs OTG (13.51 ± 10.67), P < 0.05]. Time to first flatus and soft diet were significantly shorter in TLTG group. The pain scores at all postoperative periods and administration of opioids were significantly lower in the TLTG group than in the OTG group. No significant difference in early, late and esophagojejunostomy (EJ)-related complications or 5-year recurrence free and overall survival between groups. Multivariate analysis demonstrated that body mass index [odds ratio (OR), 1.824; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.029-3.234, P = 0.040] and American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) score (OR, 3.154; 95%CI: 1.084-9.174, P = 0.035) were independent risk factors of early complications. Additionally, age was associated with ≥ 3 Clavien-Dindo classification and EJ-related complications.

Although TLTG with the modified overlap method showed similar complication rate and oncological outcome with OTG, it yields lower pain score, earlier bowel recovery, and discharge. Surgeons should perform total gastrectomy cautiously and delicately in patients with obesity, high ASA scores, and older ages.

Core Tip: The aim of the present study was to investigate the effectiveness and surgical outcomes of totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy (TLTG) using the modified overlap method compared with open total gastrectomy (OTG) using the circular stapled method. Although TLTG with the modified overlap method demonstrated similar complication rate and oncological outcome with OTG, it resulted in lower pain scores, and earlier bowel recovery and hospital discharge.

- Citation: Ko CS, Choi NR, Kim BS, Yook JH, Kim MJ, Kim BS. Totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy using the modified overlap method and conventional open total gastrectomy: A comparative study. World J Gastroenterol 2021; 27(18): 2193-2204

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v27/i18/2193.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v27.i18.2193

Laparoscopic total gastrectomy (LTG) is becoming increasingly used to treat upper or middle third gastric cancer because it shows earlier recovery and is considered less invasive[1-3]. Of the entire procedure of LTG, esophagojejunal reconstruction is the most crucial process. This is because the failure of esophagojejunostomy (EJ) such as leakage and stricture could induce the patients to suffer[4]. When performing EJ, EJ using linear stapler method is widely adopted due to its simplicity in comparison to the circular stapled method, such as overlap and functional method[5-9]. Nonetheless, the linear stapled method has a fundamental problem that it requires larger space to dissect around the distal esophagus than does the circular stapled method because the linear stapler needs to be inserted in the abdominal hiatus.

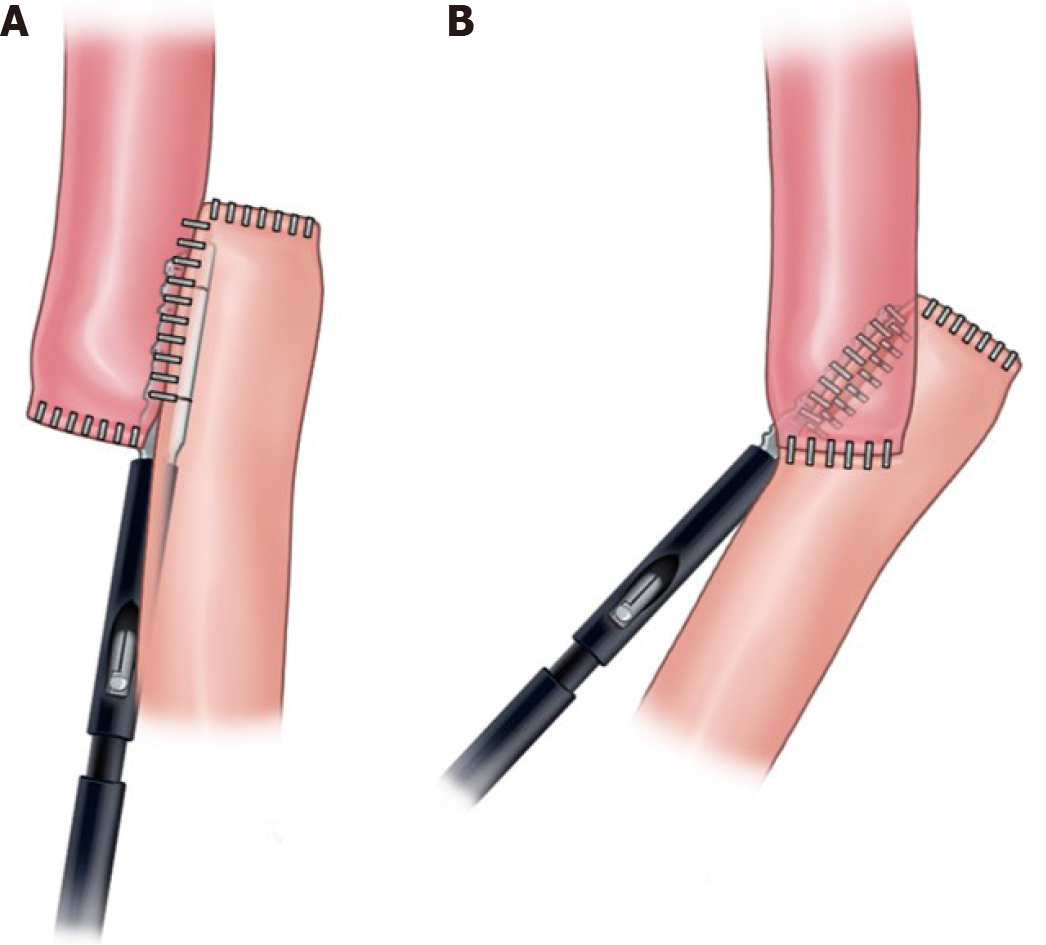

Recently, we developed a modified overlap method for totally LTG (TLTG) for overcoming these disadvantages of linear stapled method[10]. This method is performed with an intracorporeal side to side esophagojejunal anastomosis using a 45-mm linear stapler at 45° from the longitudinal direction of the esophagus (Figure 1). This procedure requires less dissection around abdominal esophagus; therefore, it can create a secure esophagojejunal anastomosis with reduced tension as circular stapled method.

Several studies have investigated the surgical outcomes of the TLTG compared with open total gastrectomy (OTG), including EJ-related complications[11,12]. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are few studies which compared TLTG with the overlap method and OTG with circular stapled method including oncological outcome.

The aim of the present study was to investigate the technical feasibility and oncological outcome of TLTG with the modified overlap method when compared with OTG with circular stapled method in the treatment of upper or middle third gastric cancer.

This study was approved by the institutional review board of the Asan Medical Center. We reviewed the retrospectively collected and analyzed data of 462 patients who underwent curative TLTG (n = 178) and OTG (n = 284) as a treatment for upper or middle third gastric cancer between March 2012 and December 2018 at Asan Medical Center. We excluded all patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, were diagnosed with esophagogastric junction cancer, underwent resection additional organs except for gall bladder, and did not have a gastric cancer diagnosis. Finally, 151 and 131 patients who underwent TLTG and OTG, respectively, were enrolled. All TLTG procedures were performed as TLTG with the modified overlap method. We evaluated TNM (tumor-node-metastasis) stage using the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), 7th edition[13]. Clinical characteristics and pathologic data were compared between TLTG and OTG groups. Additionally, we evaluated surgical outcomes, including EJ-related complications, and oncologic outcomes, including recurrence free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS). Early and late complications were defined as events occurring within or after 30 d postoperatively, respectively. EJ complications, including bleeding, leakage and stricture, were diagnosed via upper gastrointestinal series, esophagogastroduodenoscopy, computed tomography, and clinical signs. These complications were reviewed and classified based on the Clavien-Dindo classification system (CDC)[14]. Patients were matched using propensity score matching (PSM) analysis and surgical and oncological outcomes were evaluated.

We performed TLTG with modified overlap method and OTG with circular stapled method, which was similar to our previous studies[3,10]. Both procedures were performed by a single experienced surgeon who conducts approximately 300 cases of gastrectomy annually.

In the un-matched group, numerical variables were presented as the mean ± SD using the Student’s t-test or Kruskal-Wallis test. Categorical variables was performed using the Chi-square test. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed for the entire patient cohort (un-matched group) using logistic regression. Variables were included in the multivariate analysis if their univariate significance was < 0.1.

To reduce the impact of treatment selection bias and potential confounding factors in this observational study, we performed rigorous adjustments for significant differences in the baseline characteristics of patients using the logistic regression models with generalized estimating equations (GEE) with a propensity score matched set. When that technique was used, the propensity scores were estimated without considering the outcomes using multiple logistic regression analysis. A full non-parsimonious model was developed that included all the variables shown in Table 1. Model discrimination was assessed using the C statistic and model calibration was evaluated using Hosmer-Lemeshow statistics. Overall, the model was well calibrated (Hosmer-Lemeshow test; P = 0.368) with reasonable discrimination (C statistic = 0.858). We matched the two groups (1:1 ratio) using a ‘greedy nearest-neighbour’ algorithm method. The Matching balance was measured based on the standardized mean differences. A > 10% difference in the absolute value was considered significantly imbalanced.

| Variable | Total set (n = 282) | P value | SD | PSM set (1:1) (n = 122) | P value | SD | ||

| TLTG (n = 151) | OTG (n = 131) | TLTG (n = 61) | OTG (n = 61) | |||||

| Age (yr) | 60.74 ± 11.55 | 59.11 ± 11.02 | 0.231 | 0.144 | 58.30 ± 11.26 | 58.70 ± 10.65 | 0.841 | 0.037 |

| Gender | 0.257 | 0.136 | 0.847 | 0.035 | ||||

| Male | 94 (62.25) | 90 (68.70) | 40 (65.57) | 41 (67.21) | ||||

| Female | 57 (37.75) | 41 (31.30) | 21 (34.43) | 20 (32.79) | ||||

| BMI (kg/m²) | 24.57 ± 3.25 | 23.69 ± 3.21 | 0.023 | 0.273 | 24.01 ± 2.98 | 23.98 ± 2.73 | 0.957 | 0.010 |

| ASA score | 0.859 | 0.044 | 0.885 | 0.073 | ||||

| I | 30 (19.87) | 26 (19.85) | 13 (21.31) | 14 (22.95) | ||||

| II | 114 (75.50) | 97 (74.05) | 46 (75.41) | 44 (72.13) | ||||

| III | 7 (4.64) | 8 (6.11) | 2 (3.28) | 3 (4.92) | ||||

| Number of comorbidities | 0.068 | 0.222 | 0.655 | 0.083 | ||||

| 0-2 | 137 (90.73) | 126 (96.18) | 59 (75.41) | 44 (72.13) | ||||

| > 2 | 14 (9.27) | 5 (3.82) | 2 (3.28) | 3 (4.92) | ||||

| Combined operation | 0.176 | 0.161 | > 0.999 | 0 | ||||

| No | 136 (90.07) | 111 (84.73) | 55 (90.16) | 55 (90.16) | ||||

| Yes | 15 (9.93) | 20 (15.27) | 6 (9.84) | 6 (9.84) | ||||

| History of abdominal surgery | 0.061 | 0.254 | 0.846 | 0.103 | ||||

| No | 120 (79.47) | 102 (77.86) | 50 (81.97) | 48 (78.69) | ||||

| Minor surgery | 24 (15.89) | 14 (10.69) | 6 (9.84) | 6 (9.84) | ||||

| Major surgery | 7 (4.64) | 15 (11.45) | 5 (8.20) | 7 (11.48) | ||||

| Tumor size (mm, median) | 31 (22, 46) | 64 (36, 85) | < 0.001 | 0.841 | 39 (27, 62) | 50 (28, 68) | 0.865 | 0.028 |

| Pathologic tumor stage | < 0.001 | 1.012 | 0.824 | 0.085 | ||||

| I | 109 (72.19) | 38 (29.01) | 31 (50.82) | 33 (54.10) | ||||

| II | 28 (18.54) | 41 (31.30) | 19 (31.15) | 19 (31.15) | ||||

| III | 14 (9.27) | 52 (39.69) | 11 (18.03) | 9 (14.75) | ||||

In the matched group, numerical variables were reported as the means ± SD using the paired t-test. Categorical variables were performed using McNemar's test or Marginal homogeniety test. To evaluate the association between type of surgery, and complication and survival (and recurrence), the propensity score adjusted model was applied. Finally, the logistic regression model with GEE was applied using propensity score-based matching. The Cox proportional hazards model was applied using propensity score-based matching with robust standard errors. All reported P values are two-sided; values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data manipulation and statistical analyses were performed using SAS® Version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States).

The clinical variables are summarized in Table 1. There was a significant difference in body mass index (BMI), tumor size, and pathologic tumor stage before PSM between groups (all P < 0.05); however, these differences disappeared after PSM. There were no statistically significant differences in all baseline variables included in the model between groups.

All surgical outcomes and postoperative complications are shown in Table 2. There was no significant difference in operation time between groups (P = 0.351). Patients who underwent TLTG had significantly lower pain scores on all postoperative days than patients who underwent OTG. Moreover, patients in the TLTG group required significantly less analgesic and opioid administration than in the OTG group. The TLTG group reported earlier time to first flatus (3.62 ± 0.84 d vs 4.15 ± 0.87 d, P = 0.002) and soft diet (4.62 ± 2.67 d vs 7.47 ± 7.92 d, P = 0.001). Furthermore, patients who underwent TLTG stayed statistically significantly fewer days at the hospital after surgery than patients who underwent OTG (9.62 ± 5.32 d vs 13.51 ± 10.67 d; P < 0.001). No significant differences in postoperative complications were noted between the two groups (P = 0.161).

| Variable | Total set (n = 282) | P value | PSM set (1:1) (n = 122) | P value | ||

| TLTG (n = 151) | OTG (n = 131) | TLTG (n = 61) | OTG (n = 61) | |||

| Operative time (min) | 147.68 ± 29.64 | 145.24 ± 35.48 | 0.282 | 147.11 ± 25.48 | 143.46 ± 38.09 | 0.351 |

| Time to first flatus (d) | 3.73 ± 0.90 | 4.14 ± 0.81 | < 0.001 | 3.62 ± 0.84 | 4.15 ± 0.87 | 0.002 |

| Time to soft diet (d) | 4.99 ± 3.78 | 7.24 ± 6.29 | < 0.001 | 4.62 ± 2.67 | 7.47 ± 7.92 | 0.001 |

| Perioperative transfusion (n) | < 0.001 | 0.035 | ||||

| No | 145 (96.03) | 107 (81.68) | 59 (96.72) | 52 (85.25) | ||

| Yes | 6 (3.97) | 24 (18.32) | 2 (3.28) | 9 (14.75) | ||

| Hospital day after surgery (d) | 9.96 ± 6.36 | 13.06 ± 11.09 | < 0.001 | 9.62 ± 5.32 | 13.51 ± 10.67 | < 0.001 |

| Pick of pain score (VAS) | 4 (3.92) | 5 (2.51) | 0.494 | 3 (3.16) | 1 (1.05) | 0.317 |

| Pain score at postoperative day | 3.19 ± 1.04 | 3.83 ± 1.14 | < 0.001 | 3.23 ± 1.09 | 4.07 ± 1.35 | < 0.001 |

| Pain score at postoperative day 1 | 2.98 ± 1.07 | 3.76 ± 1.13 | < 0.001 | 2.97 ± 0.87 | 3.77 ± 1.07 | < 0.001 |

| Pain score at postoperative day 3 | 2.68 ± 1.17 | 3.10 ± 1.28 | < 0.001 | 2.75 ± 1.31 | 3.16 ± 1.27 | < 0.001 |

| Pain score at postoperative day 5 | 1.93 ± 1.13 | 2.61 ± 1.49 | < 0.001 | 1.82 ± 1.13 | 2.64 ± 1.21 | < 0.001 |

| Administration of analgesics (n) | 9.74 ± 8.92 | 16.22 ± 18.06 | < 0.001 | 10.61 ± 11.07 | 16.92 ± 13.72 | < 0.001 |

| Administration of opioid (n) | 2.89 ± 5.49 | 5.43 ± 11.51 | < 0.001 | 3.21 ± 6.98 | 4.48 ± 5.15 | 0.031 |

| Retrieved LN | 39.53 ± 15.59 | 41.03 ± 15.31 | 0.265 | 38.67 ± 13.82 | 38.13 ± 14.52 | 0.713 |

Postoperative complications, including EJ-related complications, are summarized in Table 3. There were no significant differences in the early and late postoperative overall complications between groups (P = 0.317 and P = 0.257, respectively). In addition, there was no difference in the incidence of patients with ≥ 3 CDC complications in the early and late postoperative periods between groups (P = 0.428 and P > 0.999, respectively). There was no significant differences in EJ-related complications. Table 4 shows the details of EJ-related complications. Five cases of EJ leakage were observed, and two cases of EJ bleeding were found. Four patients with CDC 3 complications required interventions such as endoscopic management and pigtail drainage, whereas 2 patients with CDC 2 complications fully recovered by conservative treatment. One postoperative mortality occurred due to EJ bleeding.

| Variable | Total set (n = 282) | P value | PSM set (1:1) (n = 122) | P value | ||

| TLTG (n = 151) | OTG (n = 131) | TLTG (n = 61) | OTG (n = 61) | |||

| Early complications | ||||||

| No | 119 (78.81) | 99 (75.57) | 0.518 | 48 (78.69) | 43 (70.49) | 0.317 |

| Yes | 32 (21.19) | 32 (24.43) | 13 (21.31) | 18 (29.51) | ||

| Late complications | ||||||

| No | 142 (94.04) | 125 (95.42) | 0.607 | 56 (91.80) | 59 (96.72) | 0.257 |

| Yes | 9 (5.96) | 6 (4.58) | 5 (8.20) | 2 (3.28) | ||

| CDC | 0.426 | 0.564 | ||||

| 0-2 | 138 (91.39) | 116 (88.55) | 56 (91.80) | 54 (88.52) | ||

| ≥ 3 | 13 (8.61) | 15 (11.45) | 5 (8.20) | 7 (11.48) | ||

| EJ related complications | 0.090 | 0.270 | ||||

| No | 148 (98.01) | 123 (93.89) | 59 (96.72) | 56 (91.80) | ||

| Yes | 3 (1.99) | 8 (6.11) | 2 (3.28) | 5 (8.20) | ||

| Case | Sex | Age | Primary operation | TNMstage | Early or late | Type of complication | CDC | Treatment | Hospital day |

| 1 | F | 79 | TLTG | III | Early | Bleeding | 5 | Operation | 8 |

| 2 | M | 65 | TLTG | II | Early | Leakage | 3A | Intervention | 20 |

| 3 | M | 74 | OTG | I | Early | Leakage | 2 | Conservative | 14 |

| 4 | M | 74 | OTG | I | Early | Bleeding | 3A | Intervention | 72 |

| 5 | M | 60 | OTG | I | Early | Leakage | 3A | Intervention | 48 |

| 6 | M | 66 | OTG | I | Early | Leakage | 2 | Conservative | 25 |

| 7 | M | 63 | OTG | I | Early | Leakage | 3A | Intervention | 32 |

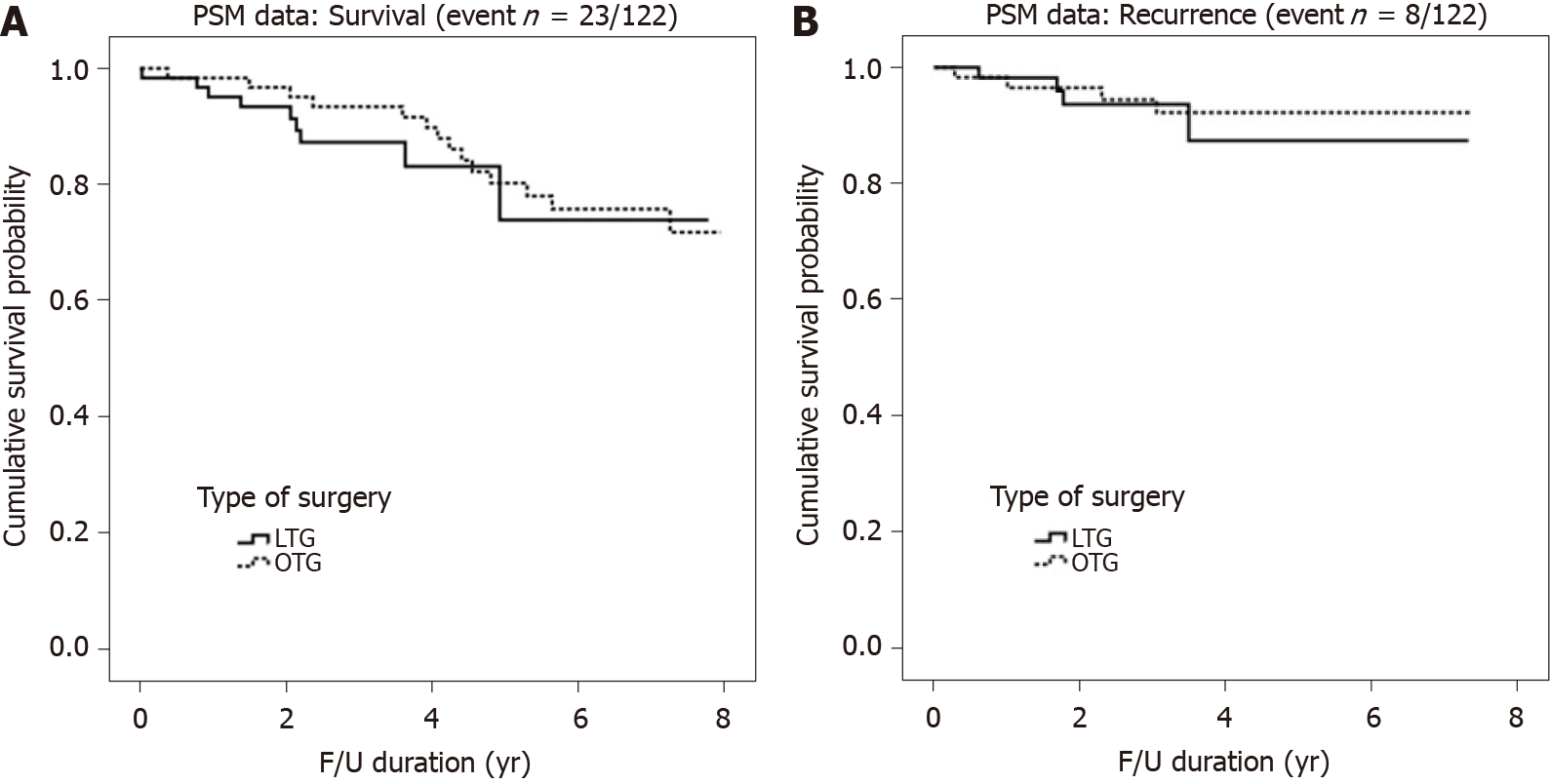

There were no significant differences in the number of retrieved lymph nodes between groups (P = 0.713). The 5-year RFS and OS are shown in Figure 2. There were no significant differences in pathologic tumor stage between groups after PSM. The 5-year RFS rates of patients who underwent TLTG and OTG were 87.7% and 92.3%, respectively; however, these differences were no significant (P = 0.653). The 5-year OS rates of patients who underwent TLTG and OTG were 74.6% and 80.4%, respectively (P = 0.476).

Tables 5 and 6 demonstrate the risk factors for postoperative complications after TLTG and OTG. BMI and American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) scores were significantly associated with the occurrence of early complications in the univariate analysis. In addition, ASA score and age were significantly associated with the incidence of ≥ 3 CDC and EJ-related complications, respectively. Multivariate analysis demonstrated that BMI [odds ratio (OR), 1.824; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.029-3.234, P = 0.040] and ASA score (OR, 3.154; 95%CI: 1.084-9.174, P = 0.035) were independent risk factors of early complications. Furthermore, multivariate analysis revealed that age was associated with ≥ 3 CDC and EJ-related complications.

| Variables | Early complications | CDC ≥ 3 complications | EJ-related complications | |||

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Type of surgery | 0.518 | 0.428 | 0.090 | |||

| TLTG | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| OTG | 1.202 (0.688-2.100) | 1.373 (0.628-3.002) | 3.209 (0.833–12.356) | |||

| Age | 0.289 | 0.051 | 0.035 | |||

| < 60 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| ≥ 60 | 1.358 (0.772-2.390) | 2.347 (0.997-5.525) | 9.220 (1.164-73.022) | |||

| BMI | 0.045 | 0.380 | 0.402 | |||

| < 25 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| ≥ 25 | 1.773 (1.012-3.109) | 1.419 (0.649-3.101) | 1.678 (0.500-5.633) | |||

| ASA score | 0.030 | 0.036 | ||||

| 1-2 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 3 | 3.224 (1.122-9.265) | 3.682 (1.088-12.456) | ||||

| Number of comorbidities | 0.342 | 0.752 | ||||

| 0-2 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| > 2 | 1.631 (0.594-4.480) | 1.406 (0.170-11.599) | ||||

| Combined operation | 0.685 | 0.381 | 0.735 | |||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 0.833 (0.346-2.008) | 0.515 (0.117-2.272) | 0.697 (0.086-5.618) | |||

| History of abdominal surgery | 0.130 | 0.323 | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 1.640 (0.864-3.111) | 1.554 (0.648-3.726) | 1.408 (0.362-5.478) | 0.622 | ||

| Tumor size | 0.521 | 0.442 | 0.053 | |||

| < 5 cm | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| ≥ 5 cm | 0.830 (0.470-1.466) | 0.521 | 0.727 (0.323-1.638) | 3.786 (0.983-14.585) | ||

| Operation time | 0.225 | 0.605 | 0.805 | |||

| < 150 min | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| ≥ 150 min | 1.414 (0.808-2.477) | 1.230 (0.562-2.692) | 1.165 (0.347-3.912) | |||

| Retrieved lymph node | 0.714 | 0.662 | 0.246 | |||

| < 30 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| ≥ 30 | 0.888 (0.471-1.676) | 1.235 (0.480-3.181) | 3.416 (0.429-27.170) | |||

| Pathologic tumor stage | 0.418 | 0.864 | 0.875 | |||

| I | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| II | 0.666 (0.328-1.351) | 1.246 (0.497-3.126) | 0.701 (0.138-3.568) | |||

| III | 0.704 (0.346-1.431) | 0.950 (0.348-2.592) | 1.119 (0.27-4.617) | |||

| Variables | Early complications | CDC ≥ 3 complications | EJ related complications | |||

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Type of surgery | ||||||

| TLTG | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| OTG | 1.275 (0.719-2.262) | 0.405 | 1.431 (0.650-3.153) | 0.373 | 3.546 (0.908-13.854) | 0.069 |

| Age | ||||||

| < 60 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥ 60 | 2.391 (1.013-5.641) | 0.047 | 9.925 (1.245-79.107) | 0.030 | ||

| BMI | ||||||

| < 25 | 1 | |||||

| ≥ 25 | 1.824 (1.029-3.234) | 0.040 | ||||

| ASA score | ||||||

| 1-2 | 1 | |||||

| 3 | 3.154 (1.084-9.174) | 0.035 | ||||

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to compare feasibility and oncological outcomes between patients who underwent TLTG with the modified overlap method and OTG. This study demonstrated that TLTG with the modified overlap method is a technically safe procedure based on acceptable postoperative complications, including EJ-related complications.

The overlap method is a widely used EJ reconstruction method in TLTG, it which can lessen the tension in the anastomosis and reduce mesentery division. This secures additional jejunum length for anastomosis[15,16]. This method involves a linear stapler for anastomosis; therefore, the area around the abdominal esophagus requires sufficient dissection. Furthermore, and space in the hiatus and length of the esophagus in which the stapler will be placed should be secured. This may lead to tension in the esophagus after anastomosis and hiatal hernia caused by excessive hiatus dissection. We have devised a novel method to minimize these risks, named the modified overlap method. We use a linear stapler; however, compared with the existing side-to-side anastomosis, less esophageal dissection is required. Further, anastomosis is completed obliquely at 45°; therefore, the resulting anastomosis is similar to when a circular stapler is used because end to side anastomosis is possible. This study proved the TLTG with this modified overlap method showed no significant difference in EJ complications when compared with OTG.

A previous comparative study of LTG and OTG reported similar EJ anastomotic complications; however, a previous large multicenter cohort study in Japan has shown that open surgery is safer for EJ reconstruction[11,12,17]. This indicates that controversy remains regarding the superior method for EJ anastomosis between OTG and LTG. Furthermore, international treatment guidelines, including the Korean gastric cancer treatment and Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines, do not yet recognize LTG as a standard treatment[18,19]. Nonetheless, our data indicate that a randomized clinical trial assessing the surgical and oncological outcomes using the modified overlap method should be conducted to confirm its safety and efficacy.

In this study, we overcame operative time and lymphadenectomy issues using the TLTG with the modified overlap method. First, laparoscopic gastrectomy surgery is longer than open gastrectomy[2,20,21]. However, the institution in which this study was conducted is a high-volume center where more than a thousand laparoscopic gastrectomies are performed annually. The lead surgeon in this study performs > 300 gastric cancer operations per year. All surgical team members in this institution are skilled and experienced; therefore, we predicted a reduced operative time while maintaining acceptable surgical and oncological outcomes. However, it may be difficult to apply the results of this study to low-volume centers or inexperienced surgeons.

Second, lymph node dissection is an important procedure in gastric cancer surgery because the oncologic outcome is dependent on a proper lymphadenectomy[22]. The AJCC recommends that ≥ 30 lymph nodes be removed for lymphadenectomy in gastric cancer[23]. In this study, there was no statistically significant difference in the number of retrieved lymph nodes between groups; ≥ 30 lymph nodes were removed in both groups. In addition, this study showed that the 5-year overall and RFS after PSM analysis did not differ between groups.

In general, the risk factors associated with surgical complications in laparoscopic gastrectomy are comorbidity, surgeon experience, age, malnutrition, gender, and chronic liver disease[24-26]. Most studies have included and analyzed patients who underwent total and distal gastrectomies. Fewer studies have analyzed total gastrectomy alone. Kosuga et al[25] and Martin et al[26] have classified total gastrectomy as a risk factor for complications (OR 1.63 and 3.13, respectively). This indicates that it is important to evaluate risk factors relative to limited total gastrectomy. Li et al[27] have shown that old age combined with splenectomy is a risk factor for overall complications after total gastrectomy. In this study, preoperative BMI and ASA scores were risk factors associated with early complications. Further, old age was a risk factor associated with EJ complications. Patients over 60-year-old with a BMI over 25 and ASA scores of ≥ 3 were more likely to have surgical complications; therefore, caution is required during surgery and careful perioperative management is necessary.

This study has some limitations. First, it is a retrospective study performed by a single experienced surgeon at a high-volume center. Therefore, our method might not be appropriate for relatively inexperienced surgeons or small-volume institutes. Second, the number of enrolled patients is relatively small; therefore, subgroup analysis, such as distinguishing between early gastric cancer and advanced gastric cancer or grouping by stage, was not possible.

In conclusion, we confirmed that TLTG with the modified overlap method had several advantages over OTG. These included a lower pain score, earlier bowel recovery, and discharge based on acceptable postoperative complications and oncological outcomes.

Although several methods of totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy (TLTG) have been reported, the best anastomosis technique of TLTG has not been conclusively established. Recently, we developed a modified overlap method for TLTG for overcoming these disadvantages of linear stapled method. This procedure requires less dissection around abdominal esophagus; therefore, it can create a secure esophagojejunal anastomosis with reduced tension as circular stapled method.

Whether is a more optimal anastomotic method of esophagojejunostomy in TLTG and open total gastrectomy (OTG) remains unclear. Especially, there was no report about comparing between TLTG with overlap method and OTG.

The aim of this study was to investigate the effectiveness and surgical outcomes including recurrence and survival of TLTG using the modified overlap method compared with OTG using the circular stapled method.

We performed 151 TLTG with modified overlap method and 131 OTG for gastric cancer between March 2012 and December 2018 at Asan Medical Center. We evaluated surgical and oncological outcomes between the two groups using propensity score matching. In addition, we analyzed risk factors associated with postoperative complications for improvement of postoperative management of gastric cancer surgery.

The patients who underwent TLTG were discharged earlier than those who underwent OTG. Time to first flatus and soft diet were significantly shorter in TLTG group. Pain score at all postoperative period and administration of opioid were significantly lower after the TLTG. No statistically significant difference was found between the two groups in terms of early, late and esophagojejunostomy-related complications. Significant differences were observed not with respect to 5-year recurrence free survival and overall survival.

TLTG with modified overlap method have favorable surgical and oncological outcomes compared with OTG. Furthermore, the surgeon should perform total gastrectomy cautiously and delicately especially with the patients with obese, high American Society of Anaesthesiologists score and old age.

Based on our results, we confirmed that the TLTG with modified overlap method has several advantages over OTG. However, this study has certain limitations. It is a retrospective study performed by a single experienced surgeon at a high-volume center, and the number of enrolled patients is relatively small.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): D, D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Balducci G, Garbarino GM, Laracca GG, Zhou XP S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Chen K, Pan Y, Zhai ST, Yu WH, Pan JH, Zhu YP, Chen QL, Wang XF. Totally laparoscopic vs open total gastrectomy for gastric cancer: A case-matched study about short-term outcomes. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e8061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Haverkamp L, Weijs TJ, van der Sluis PC, van der Tweel I, Ruurda JP, van Hillegersberg R. Laparoscopic total gastrectomy vs open total gastrectomy for cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:1509-1520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kim HS, Kim BS, Lee IS, Lee S, Yook JH. Comparison of totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy and open total gastrectomy for gastric cancer. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2013;23:323-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gong W, Li J. Combat with esophagojejunal anastomotic leakage after total gastrectomy for gastric cancer: A critical review of the literature. Int J Surg. 2017;47:18-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ebihara Y, Okushiba S, Kawarada Y, Kitashiro S, Katoh H. Outcome of functional end-to-end esophagojejunostomy in totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2013;398:475-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ito H, Inoue H, Odaka N, Satodate H, Onimaru M, Ikeda H, Takayanagi D, Nakahara K, Kudo SE. Evaluation of the safety and efficacy of esophagojejunostomy after totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy using a trans-orally inserted anvil: a single-center comparative study. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1929-1935. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jeong O, Jung MR, Kim GY, Kim HS, Ryu SY, Park YK. Comparison of short-term surgical outcomes between laparoscopic and open total gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma: case-control study using propensity score matching method. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216:184-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Okabe H, Obama K, Tanaka E, Nomura A, Kawamura J, Nagayama S, Itami A, Watanabe G, Kanaya S, Sakai Y. Intracorporeal esophagojejunal anastomosis after laparoscopic total gastrectomy for patients with gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:2167-2171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Shim JH, Yoo HM, Oh SI, Nam MJ, Jeon HM, Park CH, Song KY. Various types of intracorporeal esophagojejunostomy after laparoscopic total gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2013;16:420-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Choi M, Ko CS, Yook JH, Kim BS. Comparative outcomes between totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy with the modified overlap method for early gastric cancer and advanced gastric cancer: review of 149 consecutive cases. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne. 2020;15:437-445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Inokuchi M, Otsuki S, Fujimori Y, Sato Y, Nakagawa M, Kojima K. Systematic review of anastomotic complications of esophagojejunostomy after laparoscopic total gastrectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:9656-9665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lee JH, Nam BH, Ryu KW, Ryu SY, Park YK, Kim S, Kim YW. Comparison of outcomes after laparoscopy-assisted and open total gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2015;102:1500-1505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Union for International Cancer Control. What is TNM cancer staging system? [cited 17 March 2021]. In: Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) homepage [Internet]. Available from: https://www.uicc.org/resources/tnm. |

| 14. | Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18532] [Cited by in RCA: 24813] [Article Influence: 1181.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kawamura H, Ohno Y, Ichikawa N, Yoshida T, Homma S, Takahashi M, Taketomi A. Anastomotic complications after laparoscopic total gastrectomy with esophagojejunostomy constructed by circular stapler (OrVil™) vs linear stapler (overlap method). Surg Endosc. 2017;31:5175-5182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Son SY, Cui LH, Shin HJ, Byun C, Hur H, Han SU, Cho YK. Modified overlap method using knotless barbed sutures (MOBS) for intracorporeal esophagojejunostomy after totally laparoscopic gastrectomy. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:2697-2704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kodera Y, Yoshida K, Kumamaru H, Kakeji Y, Hiki N, Etoh T, Honda M, Miyata H, Yamashita Y, Seto Y, Kitano S, Konno H. Introducing laparoscopic total gastrectomy for gastric cancer in general practice: a retrospective cohort study based on a nationwide registry database in Japan. Gastric Cancer. 2019;22:202-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Guideline Committee of the Korean Gastric Cancer Association (KGCA); Development Working Group & Review Panel. Erratum: Korean Practice Guideline for Gastric Cancer 2018: an Evidence-based, Multi-disciplinary Approach. J Gastric Cancer. 2019;19:372-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2018 (5th edition). Gastric Cancer. 2021;24:1-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 735] [Cited by in RCA: 1336] [Article Influence: 334.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 20. | Deng Y, Zhang Y, Guo TK. Laparoscopy-assisted vs open distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: A meta-analysis based on seven randomized controlled trials. Surg Oncol. 2015;24:71-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zeng YK, Yang ZL, Peng JS, Lin HS, Cai L. Laparoscopy-assisted vs open distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: evidence from randomized and nonrandomized clinical trials. Ann Surg. 2012;256:39-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Schwarz RE, Smith DD. Clinical impact of lymphadenectomy extent in resectable gastric cancer of advanced stage. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:317-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti AI; American Joint Committee of Cancer. AJCC cancer staging manual. 7th ed. New York: Springer, 2010. |

| 24. | Kim MC, Kim W, Kim HH, Ryu SW, Ryu SY, Song KY, Lee HJ, Cho GS, Han SU, Hyung WJ; Korean Laparoscopic Gastrointestinal Surgery Study (KLASS) Group. Risk factors associated with complication following laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a large-scale korean multicenter study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:2692-2700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kosuga T, Ichikawa D, Komatsu S, Kubota T, Okamoto K, Konishi H, Shiozaki A, Fujiwara H, Otsuji E. Clinical and surgical factors associated with organ/space surgical site infection after laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:1667-1674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Martin AN, Das D, Turrentine FE, Bauer TW, Adams RB, Zaydfudim VM. Morbidity and Mortality After Gastrectomy: Identification of Modifiable Risk Factors. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20:1554-1564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Li Z, Liu Y, Bai B, Yu D, Lian B, Zhao Q. Surgical and Long-Term Survival Outcomes After Laparoscopic and Open Total Gastrectomy for Locally Advanced Gastric Cancer: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. World J Surg. 2019;43:594-603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |