Published online Apr 21, 2021. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i15.1553

Peer-review started: December 7, 2020

First decision: December 31, 2020

Revised: January 1, 2021

Accepted: March 17, 2021

Article in press: March 17, 2021

Published online: April 21, 2021

Processing time: 127 Days and 12.8 Hours

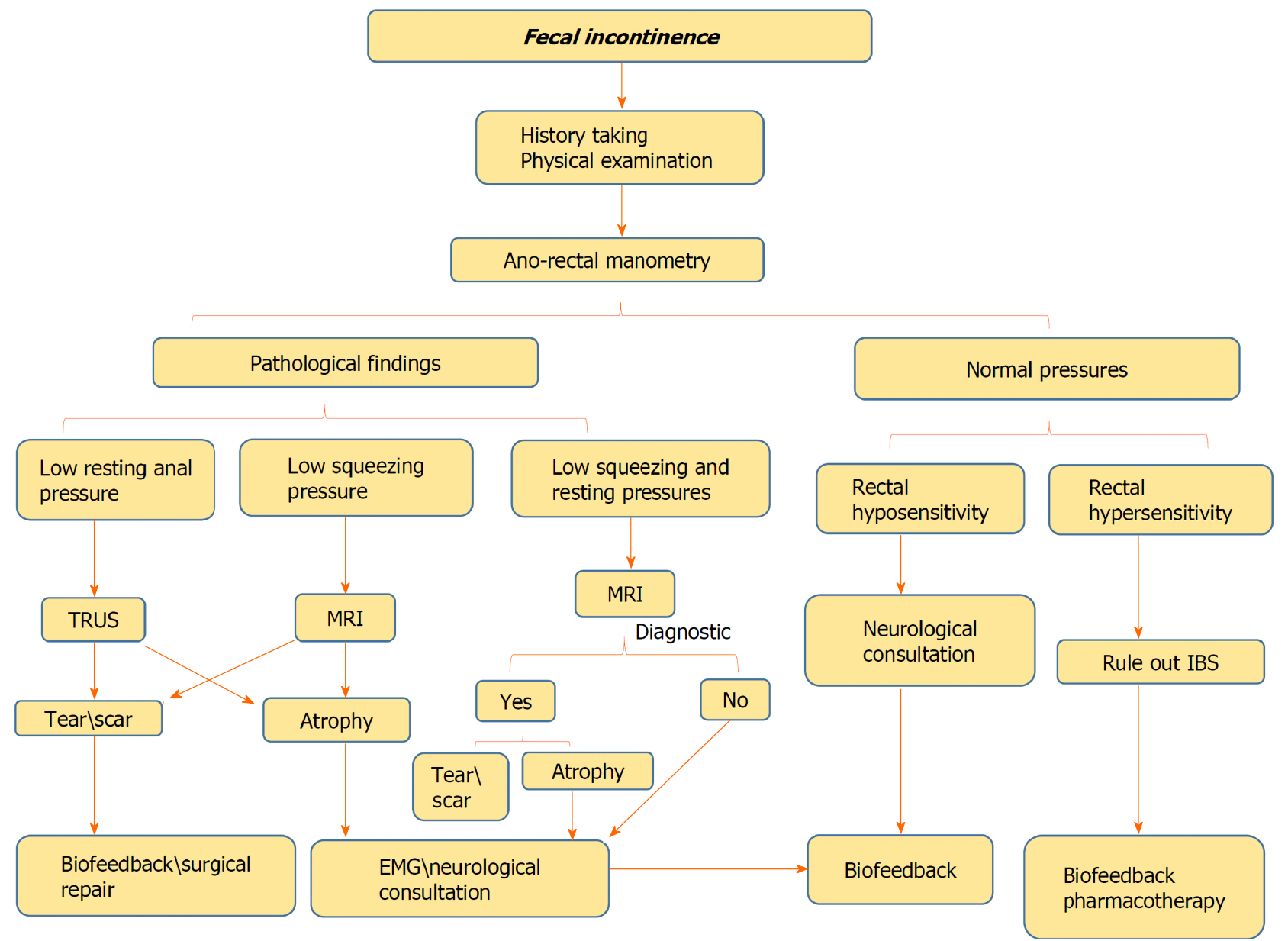

Faecal incontinence (FI) is a debilitating common end result of several diseases affecting the quality of life and leading to patient disability, morbidity, and increased societal burden. Given the various causes of FI, it is important to assess and identify the underlying pathomechanisms. Several investigatory tools are available including high-resolution anorectal manometry, transrectal ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging, and electromyography. This review article provides an overview on the causes and pathophysiology of FI and the author’s perspective of the stepwise investigation of patients with FI based on the available literature. Overall, high-resolution anorectal manometry should be the first investigatory tool for FI, followed by either transrectal ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging for anal internal sphincter and external anal sphincter injury, respectively.

Core Tip: Faecal incontinence (FI) is a debilitating symptom, which causes severe disability that deeply affect patients’ quality of life. Given the various causes of FI, it is important for clinicians to recognize the available diagnostic investigatory tools and be familiar with the clinical approach for FI. Herein, we provide a concise overview of FI and recommend a stepwise algorithm for FI investigation.

- Citation: Sbeit W, Khoury T, Mari A. Diagnostic approach to faecal incontinence: What test and when to perform? World J Gastroenterol 2021; 27(15): 1553-1562

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v27/i15/1553.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v27.i15.1553

Faecal incontinence (FI) is defined as the recurrent involuntary passage of rectal contents (solid or liquid stool) through the anal canal, and the inability to delay evacuation until socially convenient. Crucial factors to consider when defining FI include the duration of symptoms for at least 1 mo and age of onset of at least 4 years with previously attained control[1-3]. FI is considered to be a prevalent disorder with a considerable economic burden, but due to embarrassment, it is generally underreported; hence, its true prevalence is challenging to assess[4]. The prevalence of FI in the adult population of the United States is estimated to be 0.8%-6.2%[5]. The prevalence of FI increases with age from approximately 3% in the age group of 20 to 29 years to 16% in people aged ≥ 70 years[6]. A systematic review by Sharma et al[7] of over 30 studies estimated a prevalence of 1.4% to 19.5%. This discrepancy was clarified by variance in data collection methods applied and FI definition. Unsurprisingly, lower rates of FI were reported in personal interviews compared with anonymous questionnaires. The prevalence of FI is similar in both males and females, while the pathogenesis is often dissimilar between sexes.

FI has important consequences on social activities and quality of life as well as significant economic burden attributable to diagnostics, medications, instruments, procedures, and reduced work ability[8]. FI is regularly classified from a clinical point of view as: urge incontinence (discharge despite active efforts to constrict anal sphincters), passive incontinence (involuntary discharge with no awareness), and faecal seepage (leakage of stool with normal continence and evacuation)[2].

Numerous causes and associated conditions are linked to FI such as anal sphincter dysfunction, rectal disorders, neurological diseases, malignant diseases, psychiatric conditions, and other disease[8]. One major challenge in the management of FI is the hitch in correlating objective with subjective parameters.

In this review article, we shed light on the clinical evaluation and workup of patients with FI, from history taking to diagnostics including high-resolution anorectal manometry (HRAM), transrectal ultrasound (TRUS), perineal ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvic floor including MR proctography, and nerve studies such as anal sphincter electromyography (EMG). The purpose of the review is to provide a practical tool box for clinicians to use when evaluating patients with FI.

FI represents a final pathway of several traumatic and non-traumatic disorders. The most non-traumatic causes include anal sphincters and rectal dysfunctions as well as various inflammatory, congenital, structural, metabolic, neurological, muscular, psychological and functional diseases (Table 1). Alterations in bowel habits, such as diarrhoea for any reason (including inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel disease) and constipation with paradoxical diarrhoea and overflow incontinence are considered to be among the most established risk factors for FI[9]. The most common anal sphincters structural traumatic causes leading to FI are related to obstetrical trauma during vaginal delivery, anorectal surgical procedures including anorectal dilation, haemorrhoidectomy, fistulotomy, fistulectomy, sphincterotomy, rectal prolapse repair, and after ileo-anal reconstructive surgeries[10-12]. Many patients with neurological disorders affecting the brain, spinal cord or peripheral nervous system have FI because of impaired anal sphincter control, reduced or absent anorectal sensibility or abnormal anorectal reflexes. Patients with diabetes may have neuropathy of the anal canal and some have chronic diarrhoea. Connective tissue diseases, remarkable scleroderma, myopathy and atrophy of the internal anal sphincter (IAS) may lead to FI. Rectal surgery may disturb the reservoir function of the rectum as seen in patients after anterior resection surgery. Additionally, pelvic radiotherapy may lead to FI.

| Congenital neurological | Spina bifida |

| Acquired neurological | Pudendal neuropathy; Spinal injury/surgery; Demyelinating diseases; Degenerative diseases; Neurological malignancy |

| Congenital structural disease | Imperforate anus; Cloacal anomalies |

| Acquired structural disease | Vaginal delivery; Obstetric trauma; Ano-rectal surgery; Ano-rectal trauma |

| Gastrointestinal diseases | Inflammatory bowel disease; Irritable bowel syndrome; Radiation proctitis; Microscopic colitis; Malabsorption |

| Neoplastic | Hypersecretory tumours; Colorectal cancer; Ana cancer |

| Psychiatric | Psychiatric diseases |

| Medications | Diarrheal agents; Chemotherapy |

It is important in the early stages of FI evaluation to search for possible causes and risk factors during careful detailed history taking in order to route diagnostics accordingly. The main symptoms of faecal incontinence are the progressive loss of control of rectal contents including solids stool and liquids. Urge incontinence is specified by the patient’s awareness to defecation call but inability to constrict the external anal sphincter (EAS) sufficiently until reaching the toilet, and many patients report “accidents” within a few seconds or minutes. Involuntary discharge without awareness is categorized as passive incontinence and generally caused by disturbed sensation capability of the rectum and anal canal. It is imperative to identify discrete disparities in relation to various triggers such as daytime vs night time, physical activity, cough, stress, stool consistency, or food intake. Other secondary symptoms of FI may arise due to stool leakage including pruritus, perianal skin irritation, and infection as well as urinary tract infections. Notably, these secondary symptoms may be the chief complaints prompting patients to seek medical care without mentioning FI. Moreover, FI may have other important related conditions, which mandates direct exploration with the patient such as urinary incontinence, vaginal bulging (rectocele, cystocele), rectal prolapse, altered bowel habits, defecation disorders, and rectal bleeding.

Physical examination of the anorectal region is of paramount importance and starts with a visual inspection to search for leaked stool, skin irritation and infections, haemorrhoids, fistulas opening, and anal fissures[13]. During digital rectal examination, the experienced index finger is capable of affording a general estimation of the anal resting and squeeze pressures. Moreover, coordinated relaxation of the pelvic floor muscles during straining can be addressed as well during Valsalva manoeuver to search for possible defecation disorders (i.e. functional anismus)[14-16].

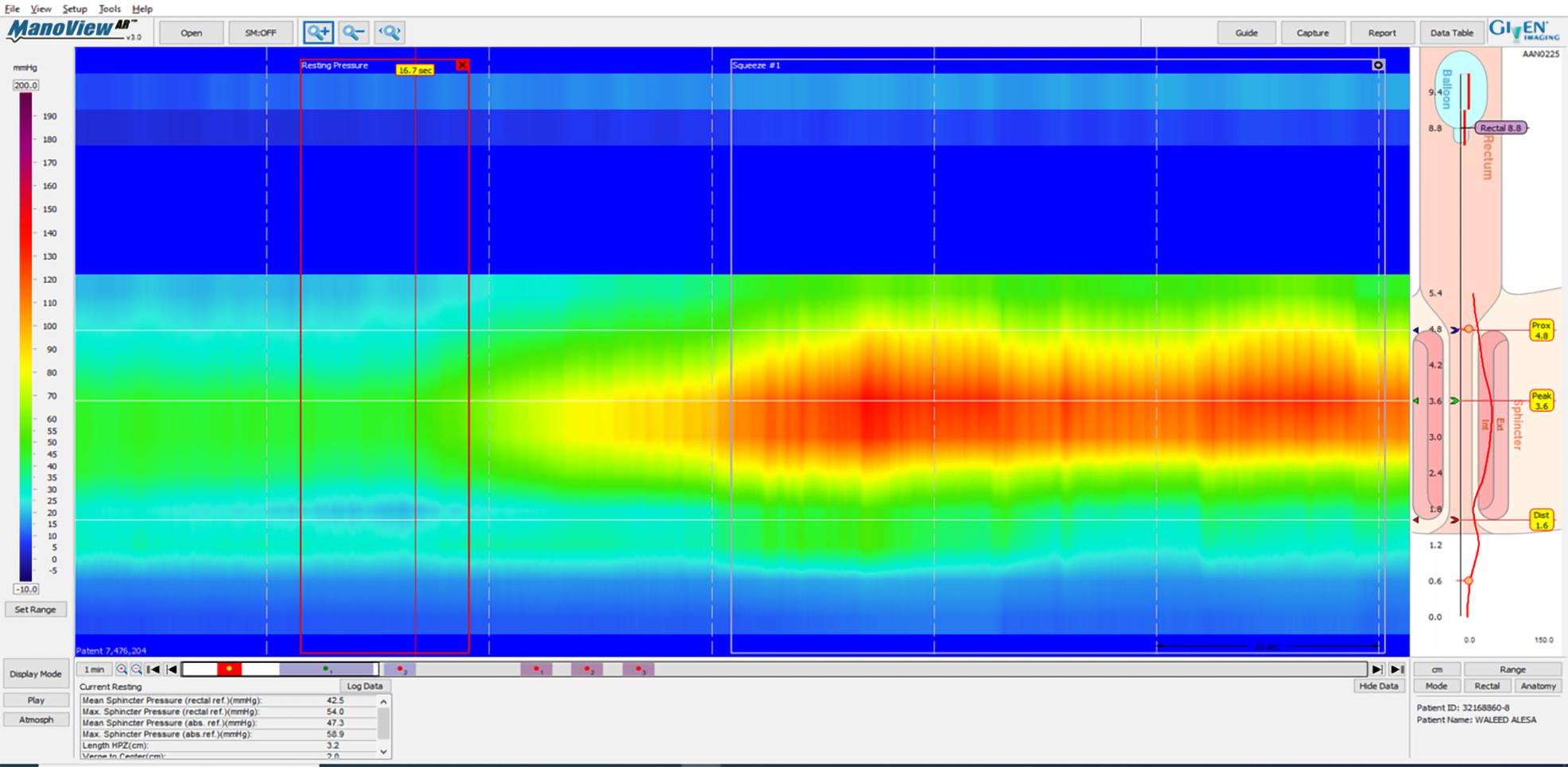

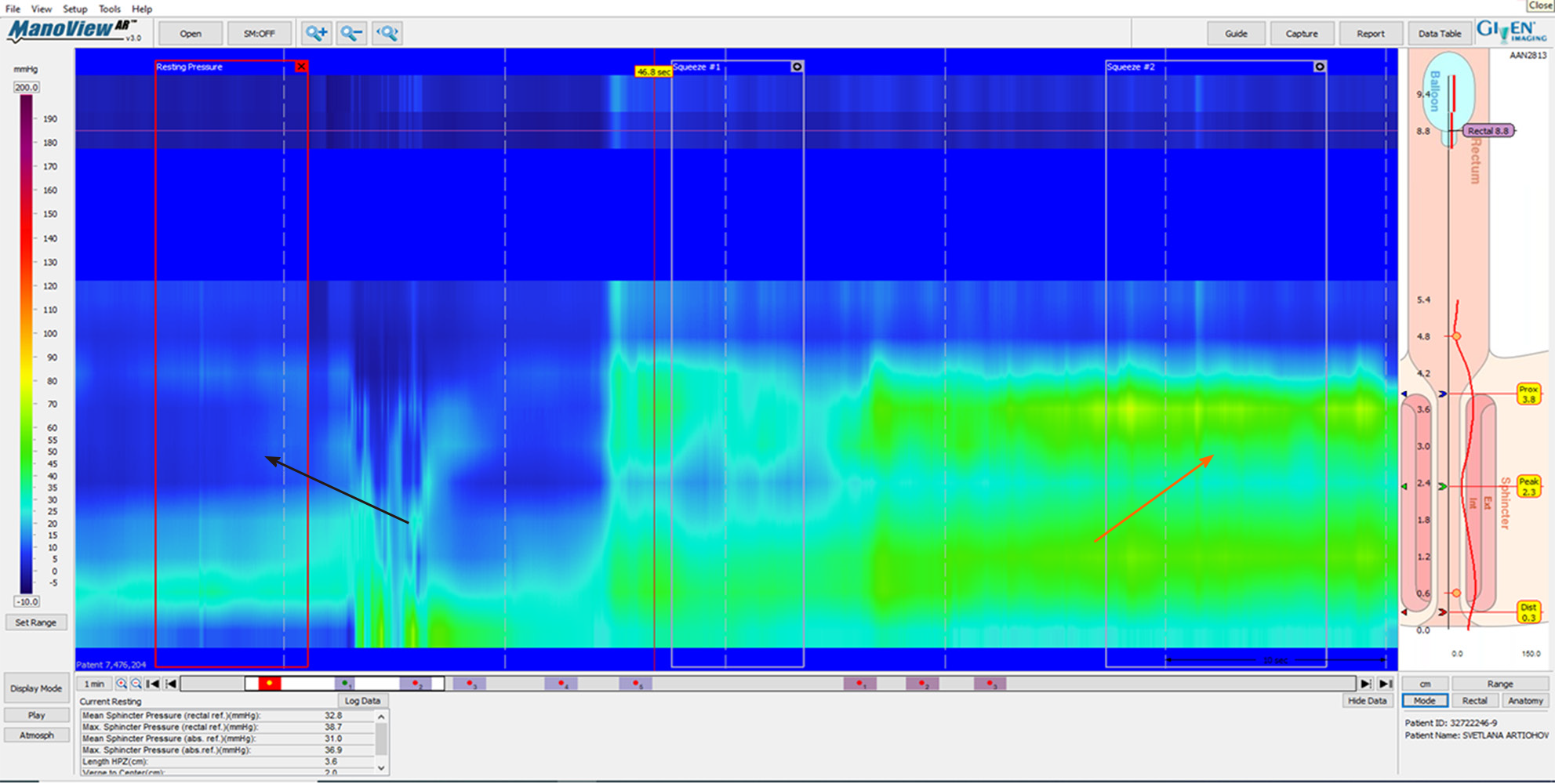

According to American College of Gastroenterology guidelines, in cases of FI, it is worth testing with AM[17]. HRAM is an important diagnostic tool for the assessment of anorectal motor and sensory function[18]. The utilization of HRAM is a necessary diagnostic key tool in the evaluation of FI, as it enhances the understanding of the underlying pathophysiological bases of FI, permitting the delivering of optimal therapy for each specific patient. HRAM, which provides a dynamic recording of the anal sphincters and intraluminal rectal pressures, is considered to be the best-established diagnostic tool that permits an objective evaluation of several factors of anal and rectal function including basal tone and contractility, recto-anal coordination, and reflex function (such as recto-anal inhibitory reflux) as well as rectal sensation thresholds[18,19], which is an important predictor of response to biofeedback training[19]. The recently established international anorectal physiology working group published a consensus guideline paper that proposes a practical standardized protocol for the performance and analysis of anorectal manometry, named the London Classification[20]. Several manometric findings may be linked to FI such as impaired anal sphincter resting pressure tone (hypotension) and impaired squeeze pressure (hypo-contractility) (Figures 1 and 2). Moreover, HRAM enables the assessment of abnormal rectal sensitivity both hypersensitivity and hyposensitivity, two conditions that may cause FI in different manners. Rectal sensation is assessed by inflating a balloon in the rectum and recording balloon volumes needed to produce the first sensation, urge, and discomfort[20]. Rectal hyposensitivity can be caused by neuropathy, mucosal inflammation, or fibrosis and may lead to patient unawareness to the presence of stool in the rectum leading to accumulation of stool and incontinence. Rectal hypersensitivity may lead to urge incontinence and is common among patients with irritable bowel syndrome[13].

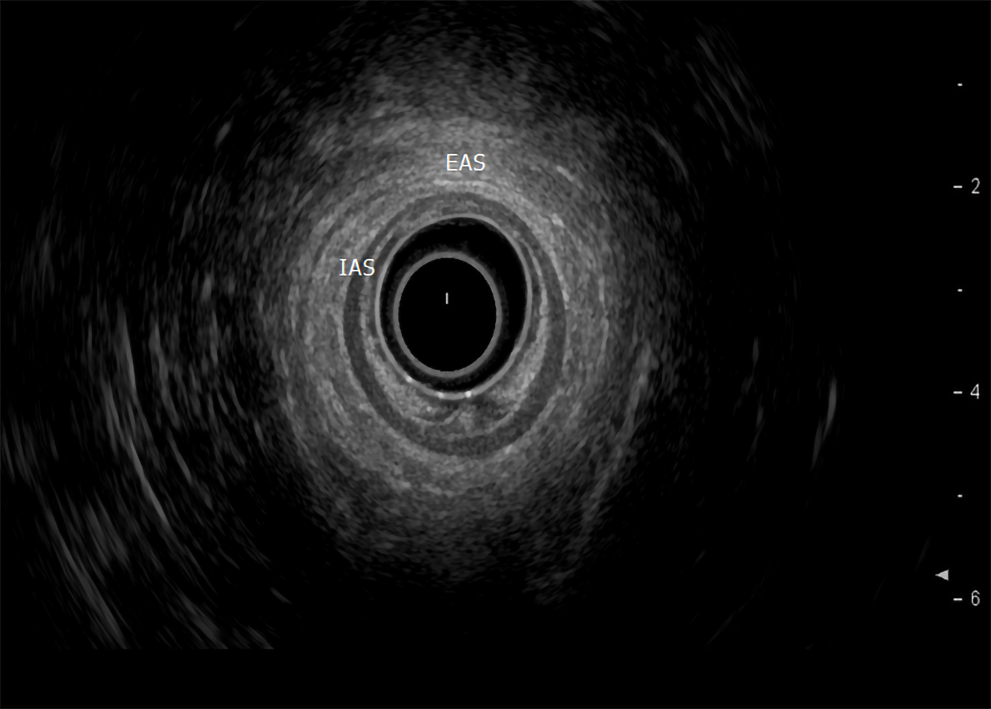

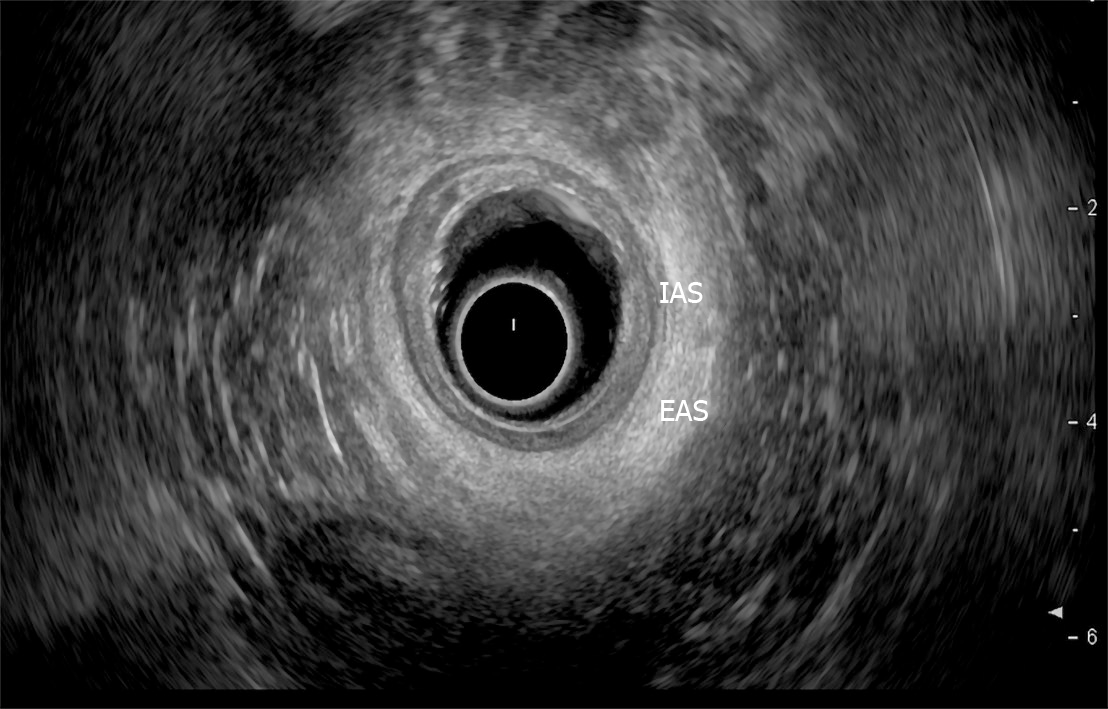

In incontinent patients with reduced anal pressures, especially when surgery is being considered, the anatomic integrity of the anal sphincters, rectal wall, and puborectalis muscle region should be evaluated by either endoscopic ultrasound or MRI[17]. Although, both tests are considered overlapping in identifying abnormalities including scars, defects, marked focal thinning or atrophy however, every test has its uniqueness and diagnostic capabilities. While ultrasound is superior in identifying IAS tears, EAS atrophy is more identified by MRI[21,22]. Additionally, discriminating between an external anal sphincter tear and scar is better with MRI[17].

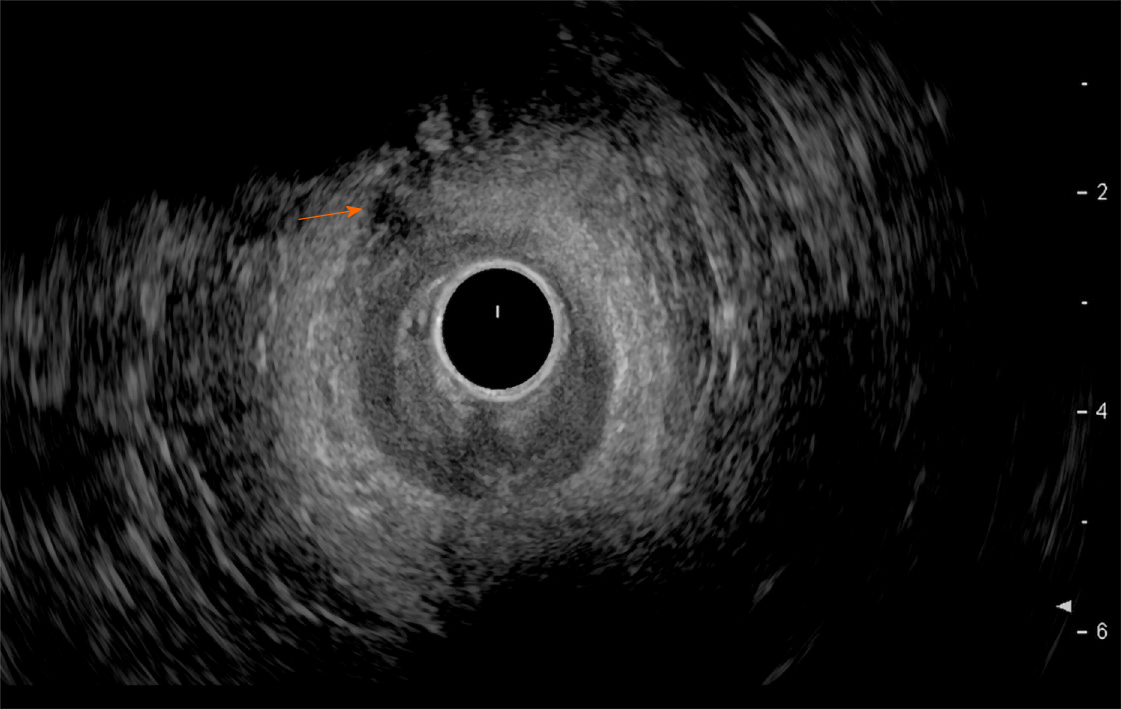

Endoscopic ultrasound: TRUS or endoanal ultrasound (EAUS) is a simple, well tolerated, widely available examination considered the gold standard in investigating the anal sphincter integrity[23,24] (Figure 3). However, its sensitivity and accuracy in identifying sphincter injuries is debated and operator-dependent[25]. Gold et al[26] reported that the interobserver agreement in diagnosing sphincter defects and IAS measurements by EAUS is very good, and better than EAS measurements. Common structural pathologies in patients suffering from FI that are easily identified by EAUS include IAS discontinuity (defect), IAS atrophy (identified by diffuse thinning of the sphincter to less than 1 mm thickness (Figure 4)[27], and EAS discontinuity (defect) or scar manifested as focal thinning (Figure 5)[19,28]. On the other hand, precise determination of EAS atrophy is difficult with EAUS due to its inferiority in determining the EAS boundaries and its inability to distinguish between normal muscle tissue and fatty infiltration[29]. Indeed, EAS atrophy is defined by diffuse reduction in muscle bulk on serial images below the level of the puborectalis, to the point where the muscle is barely identifiable[21]. The leading cause of FI is anal sphincter injury originating from vaginal delivery in females, and it may result from direct anal sphincter laceration or indirectly from sphincter innervation damage[29].

Two-dimensional EAUS, which allows cross sectional images only in the axial plane, remains the mainstay of sphincter inspection[24]; however it does not achieve accurate longitudinal measurements necessary for planning complete surgical intervention. On the other hand, three-dimensional EAUS enables the determination of length, thickness, area, and volume measurements by producing a digital volume that can be seen from any plane[29], and is displayed as either multiplanar images or tomographic slicing, thus allowing more accurate defect visualization[24].

MRI: MRI is expensive, not readily available, and not tolerated by claustrophobic patients and is unsuitable in patients with pacemakers, defibrillators, and other metal implants[29]. Two modalities of MRI are available in clinical practice: the invasive endoanal MRI using endoluminal coils and the non-invasive external phased-array. Both modalities are comparable in identifying EAS defects[30] and atrophy[31]. Compared to EAUS, the accuracy of endoanal MRI in diagnosing IAS defects is lower[32]. Several studies have reported that EAUS and endoanal MRI are equivalent in diagnosing EAS injuries[22,32,33]; however, endo-anal MRI allows better distinction between fat and muscle and in identifying scars[27]. This property underscores the diagnostic ability of EAUS in detecting focal EAS thinning and structural lesions[34-37]. Interestingly, only moderate agreement between EAUS and external phased-array MRI in diagnosing obstetric injuries, which represent the main aetiology for FI, has been reported[38]. Recently, magnetic resonance defecography has gradually emerged as a modern modality substituting the traditional X-ray based defecography. It is non-invasive test that uses MRI to obtain images at various stages of defecation to evaluate how well the pelvic muscles are working and provide insights into rectal function. Magnetic resonance defecography can provide important functional disorders related to the defecation process as well as various important structural abnormalities associated with FI and other pelvic floor disorders. These structural abnormalities include rectocele, enterocele, anorectal descent, and descending perineum[39]. The identification may impact the kind of surgical treatments[40].

A neurophysiological assessment of the anorectum includes an assessment of the conduction of the pudendal and spinal nerves using EMG examination of the sphincter. This test is of particular significance when surgery is being considered; however its availability is mainly reserved for research purposes and its clinical application has been declining recently in many countries[41,42]. However, EMG use has been advocated in patients with refractory symptoms, suspected to originate from neurogenic sphincter weakness especially when it is assumed to result from sacral root injury, it is advocated to assess rectal sensation and compliance by needle EMG of the anal sphincter[43].

FI is considered to be a prevalent disorder with a considerable economic burden, but due to embarrassment it is generally underreported. FI impacts severely patients’ quality of life, leading to various organic and psychological comorbidities. Detailed history taking and anamnesis by physician is mandatory to define the patient’s main complaints with a focus on risk factors for FI and whether passive or urge FI is dominant. Moreover, digital rectal examination is of paramount importance to assess anorectal sensation, anal sphincter resting and importantly the squeeze pressures as well. HRAM is an important initial diagnostic modality to start with, as it can provide crucial information about the anal sphincter functions and can evaluate rectal sensation capability using balloon dilation in the rectum. The anatomic integrity of the anal sphincters, rectal wall, and puborectalis muscle region should be evaluated by either TRUS or MRI. Although, both tests are considered overlapping in identifying abnormalities including scars, defects, marked focal thinning or atrophy, every test has its own uniqueness and diagnostic capabilities. While TRUS is superior in identifying internal anal sphincter tears, external anal sphincter atrophy is more identified by MRI. Additionally, discriminating between an external anal sphincter tear and scar is better with MRI. Figure 6 demonstrates the authors’ perspective of the structured, step-by-step approach for the evaluation and diagnosis of FI. Still, the place of EMG in the evaluation of FI needs to be explored. Finally, this recommended approach should aid clinicians in the stepwise management of patients with FI.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Israel

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gong J S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Wald A. Clinical practice. Fecal incontinence in adults. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1648-1655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Rao SS; American College of Gastroenterology Practice Parameters Committee. Diagnosis and management of fecal incontinence. American College of Gastroenterology Practice Parameters Committee. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1585-1604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 242] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Paquette IM, Varma MG, Kaiser AM, Steele SR, Rafferty JF. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons' Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Fecal Incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:623-636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bharucha AE, Dunivan G, Goode PS, Lukacz ES, Markland AD, Matthews CA, Mott L, Rogers RG, Zinsmeister AR, Whitehead WE, Rao SS, Hamilton FA. Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and classification of fecal incontinence: state of the science summary for the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) workshop. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:127-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 213] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Pretlove SJ, Radley S, Toozs-Hobson PM, Thompson PJ, Coomarasamy A, Khan KS. Prevalence of anal incontinence according to age and gender: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17:407-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ditah I, Devaki P, Luma HN, Ditah C, Njei B, Jaiyeoba C, Salami A, Ditah C, Ewelukwa O, Szarka L. Prevalence, trends, and risk factors for fecal incontinence in United States adults, 2005-2010. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:636-43.e1-2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sharma A, Yuan L, Marshall RJ, Merrie AE, Bissett IP. Systematic review of the prevalence of faecal incontinence. Br J Surg. 2016;103:1589-1597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Duelund-Jakobsen J, Worsoe J, Lundby L, Christensen P, Krogh K. Management of patients with faecal incontinence. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2016;9:86-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Andrews CN, Bharucha AE. The etiology, assessment, and treatment of fecal incontinence. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;2:516-525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ternent CA, Fleming F, Welton ML, Buie WD, Steele S, Rafferty J; American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. Clinical Practice Guideline for Ambulatory Anorectal Surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:915-922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wallenhorst T, Bouguen G, Brochard C, Cunin D, Desfourneaux V, Ropert A, Bretagne JF, Siproudhis L. Long-term impact of full-thickness rectal prolapse treatment on fecal incontinence. Surgery. 2015;158:104-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Markland AD, Dunivan GC, Vaughan CP, Rogers RG. Anal Intercourse and Fecal Incontinence: Evidence from the 2009-2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:269-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Dobben AC, Terra MP, Deutekom M, Gerhards MF, Bijnen AB, Felt-Bersma RJ, Janssen LW, Bossuyt PM, Stoker J. Anal inspection and digital rectal examination compared to anorectal physiology tests and endoanal ultrasonography in evaluating fecal incontinence. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:783-790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Eckardt VF, Kanzler G. How reliable is digital examination for the evaluation of anal sphincter tone? Int J Colorectal Dis. 1993;8:95-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hallan RI, Marzouk DE, Waldron DJ, Womack NR, Williams NS. Comparison of digital and manometric assessment of anal sphincter function. Br J Surg. 1989;76:973-975. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Mimura T, Kaminishi M, Kamm MA. Diagnostic evaluation of patients with faecal incontinence at a specialist institution. Dig Surg. 2004;21:235-41; discussion 241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wald A, Bharucha AE, Cosman BC, Whitehead WE. ACG clinical guideline: management of benign anorectal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1141-57; (Quiz) 1058. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Scott SM, Carrington EV. The London Classification: Improving Characterization and Classification of Anorectal Function with Anorectal Manometry. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2020;22:55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Carrington EV, Scott SM, Bharucha A, Mion F, Remes-Troche JM, Malcolm A, Heinrich H, Fox M, Rao SS; International Anorectal Physiology Working Group and the International Working Group for Disorders of Gastrointestinal Motility and Function. Expert consensus document: Advances in the evaluation of anorectal function. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15:309-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 20.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Carrington EV, Heinrich H, Knowles CH, Fox M, Rao S, Altomare DF, Bharucha AE, Burgell R, Chey WD, Chiarioni G, Dinning P, Emmanuel A, Farouk R, Felt-Bersma RJF, Jung KW, Lembo A, Malcolm A, Mittal RK, Mion F, Myung SJ, O'Connell PR, Pehl C, Remes-Troche JM, Reveille RM, Vaizey CJ, Vitton V, Whitehead WE, Wong RK, Scott SM; All members of the International Anorectal Physiology Working Group. The international anorectal physiology working group (IAPWG) recommendations: Standardized testing protocol and the London classification for disorders of anorectal function. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32:e13679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 36.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bharucha AE, Fletcher JG, Harper CM, Hough D, Daube JR, Stevens C, Seide B, Riederer SJ, Zinsmeister AR. Relationship between symptoms and disordered continence mechanisms in women with idiopathic faecal incontinence. Gut. 2005;54:546-555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | West RL, Dwarkasing S, Briel JW, Hansen BE, Hussain SM, Schouten WR, Kuipers EJ. Can three-dimensional endoanal ultrasonography detect external anal sphincter atrophy? A comparison with endoanal magnetic resonance imaging. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2005;20:328-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Talbot IC, Nicholls RJ, Bartram CI. Anal endosonography for identifying external sphincter defects confirmed histologically. Br J Surg. 1994;81:463-465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 245] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Abdool Z, Sultan AH, Thakar R. Ultrasound imaging of the anal sphincter complex: a review. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:865-875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Jiang AC, Panara A, Yan Y, Rao SSC. Assessing Anorectal Function in Constipation and Fecal Incontinence. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2020;49:589-606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gold DM, Halligan S, Kmiot WA, Bartram CI. Intraobserver and interobserver agreement in anal endosonography. Br J Surg. 1999;86:371-375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Engin G. Endosonographic imaging of anorectal diseases. J Ultrasound Med. 2006;25:57-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Dvorkin LS, Chan CL, Knowles CH, Williams NS, Lunniss PJ, Scott SM. Anal sphincter morphology in patients with full-thickness rectal prolapse. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:198-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Albuquerque A. Endoanal ultrasonography in fecal incontinence: Current and future perspectives. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;7:575-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 30. | Terra MP, Beets-Tan RG, van Der Hulst VP, Dijkgraaf MG, Bossuyt PM, Dobben AC, Baeten CG, Stoker J. Anal sphincter defects in patients with fecal incontinence: endoanal vs external phased-array MR imaging. Radiology. 2005;236:886-895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Terra MP, Beets-Tan RG, van der Hulst VP, Deutekom M, Dijkgraaf MG, Bossuyt PM, Dobben AC, Baeten CG, Stoker J. MRI in evaluating atrophy of the external anal sphincter in patients with fecal incontinence. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:991-999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Malouf AJ, Williams AB, Halligan S, Bartram CI, Dhillon S, Kamm MA. Prospective assessment of accuracy of endoanal MR imaging and endosonography in patients with fecal incontinence. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175:741-745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Dobben AC, Terra MP, Slors JF, Deutekom M, Gerhards MF, Beets-Tan RG, Bossuyt PM, Stoker J. External anal sphincter defects in patients with fecal incontinence: comparison of endoanal MR imaging and endoanal US. Radiology. 2007;242:463-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Williams AB, Bartram CI, Modhwadia D, Nicholls T, Halligan S, Kamm MA, Nicholls RJ, Kmiot WA. Endocoil magnetic resonance imaging quantification of external anal sphincter atrophy. Br J Surg. 2001;88:853-859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Bartram C, Halligan S. Endoanal MR is really complementary to endoanal US. Radiology. 2000;216:918-920. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Rociu E, Stoker J, Zwamborn AW, Laméris JS. Endoanal MR imaging of the anal sphincter in fecal incontinence. Radiographics. 1999;19 Spec No:S171-S177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Rociu E, Stoker J, Eijkemans MJ, Schouten WR, Laméris JS. Fecal incontinence: endoanal US vs endoanal MR imaging. Radiology. 1999;212:453-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Kirss J, Huhtinen H, Niskanen E, Ruohonen J, Kallio-Packalen M, Victorzon S, Victorzon M, Pinta T. Comparison of 3D endoanal ultrasound and external phased array magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of obstetric anal sphincter injuries. Eur Radiol. 2019;29:5717-5722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Piloni V, Bergamasco M, Melara G, Garavello P. The clinical value of magnetic resonance defecography in males with obstructed defecation syndrome. Tech Coloproctol. 2018;22:179-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Thapar RB, Patankar RV, Kamat RD, Thapar RR, Chemburkar V. MR defecography for obstructed defecation syndrome. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2015;25:25-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Bharucha AE, Daube J, Litchy W, Traue J, Edge J, Enck P, Zinsmeister AR. Anal sphincteric neurogenic injury in asymptomatic nulliparous women and fecal incontinence. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;303:G256-G262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Law PJ, Kamm MA, Bartram CI. A comparison between electromyography and anal endosonography in mapping external anal sphincter defects. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990;33:370-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Weledji EP. Electrophysiological Basis of Fecal Incontinence and Its Implications for Treatment. Ann Coloproctol. 2017;33:161-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |