Published online Apr 14, 2021. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i14.1497

Peer-review started: January 14, 2021

First decision: February 10, 2021

Revised: February 21, 2021

Accepted: March 17, 2021

Article in press: March 17, 2021

Published online: April 14, 2021

Processing time: 84 Days and 23.2 Hours

Nucleos(t)ide analogs (NAs) cessation in chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients remains a matter of debate in clinical practice. Current guidelines recommend that patients with hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) seroconversion discontinue NAs after relatively long-term consolidation therapy. However, many patients fail to achieve HBeAg seroconversion after the long-term loss of HBeAg, even if hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) loss occurs. It remains unclear whether NAs can be discontinued in this subset of patients.

To investigate the outcomes and factors associated with HBeAg-positive CHB patients with HBeAg loss (without hepatitis B e antibody) after cessation of NAs.

We studied patients who discontinued NAs after achieving HBeAg loss. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to identify predictors for virological relapse after cessation of NAs. The cut-off value of the consolidation period was confirmed using receiver operating characteristic curves; we confirmed the cut-off value of HBsAg according to a previous study. The log-rank test was used to compare cumulative relapse rates among groups. We also studied patients with CHB who achieved HBeAg seroconversion and compared their cumulative relapse rates. Propensity score matching analysis (PSM) was used to balance baseline characteristics between the groups.

We included 83 patients with HBeAg loss. The mean age of these patients was 32.1 ± 9.5 years, and the majority was male (67.5%). Thirty-eight patients relapsed, and the cumulative relapse rate at months 3, 6, 12, 24, 36, 60, 120, and 180 were 22.9%, 36.1%, 41.0%, 43.5%, 45.0%, 45.0%, 45.0%, and 52.8%, respectively. Twenty-six (68.4%) patients relapsed in the first 3 mo after NAs cessation, and 35 patients (92.1%) relapsed in the first year after NAs cessation. Consolidation period (≥ 24 mo vs < 24 mo) (HR 0.506, P = 0.043) and HBsAg at cessation (≥ 100 IU/mL vs < 100 IU/mL) (HR 14.869, P = 0.008) were significant predictors in multivariate Cox regression. In the PSM cohort, which included 144 patients, there were lower cumulative relapse rates in patients with HBeAg seroconversion (P = 0.036).

HBeAg-positive CHB patients with HBeAg loss may be able to discontinue NAs therapy after long-term consolidation, especially in patients with HBsAg at cessation < 100 IU/mL. Careful monitoring, especially in the early stages after cessation, may ensure a favorable outcome.

Core Tip: A considerable proportion of patients fail to achieve hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) seroconversion after the long-term loss of HBeAg, even if hepatitis B surface antigen loss occurs. It remains unclear whether nucleos(t)ide analogs (NAs) can be discontinued in this subset of patients. The current study included patients who discontinued NAs after achieving HBeAg loss (without hepatitis B e antibody) for long periods since 2001. It was concluded that these patients may be able to discontinue NAs therapy after long-term consolidation. HBsAg at cessation < 100 IU/mL predicts sustained virological response after NAs cessation. Careful monitoring, especially in the early stages after cessation, may ensure a favorable outcome.

- Citation: Xue Y, Zhang M, Li T, Liu F, Zhang LX, Fan XP, Yang BH, Wang L. Exploration of nucleos(t)ide analogs cessation in chronic hepatitis B patients with hepatitis B e antigen loss. World J Gastroenterol 2021; 27(14): 1497-1506

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v27/i14/1497.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v27.i14.1497

Nucleos(t)ide analogues (NAs) are primary therapeutic agents for hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection; they significantly improved outcomes in patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB)[1-3]. However, taking these medicines for life presents a substantial obstacle to compliance among patients with CHB. Therefore, NAs withdrawal is being studied[4-6].

Hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) has been proved to be associated with several immunomodulatory functions in HBeAg-positive patients with CHB, including replication of HBV and responses of the host to the virus[7,8]. Current guidelines recommend that patients with HBeAg seroconversion discontinue NAs after relatively long-term consolidation therapy[1-3]. Although only a small number of patients achieved a loss of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), our previous study showed acceptable cumulative relapse rates for HBeAg-positive patients who achieved HBeAg seroconversion[5].

A considerable proportion of patients fail to achieve HBeAg seroconversion after the long-term loss of HBeAg, even if HBsAg loss occurs[9,10]. It remains unclear whether NAs can be discontinued in this subset of patients[1-3,11,12]. In an outcome study of patients with CHB and HBeAg loss after NAs cessation, 17 of 25 patients maintained sustained virological response (SVR)[10]. Another study also included CHB patients with HBeAg loss and the off-treatment virologic responses remained poor[13]. However, these studies were not explicitly designed for this subpopulation; furthermore, the sample sizes were small, and the consolidation periods were short[10,13]. Therefore, the persuasiveness of the conclusions was limited.

Some patients in our previous cohort[5,14] discontinued NAs after achieving HBeAg loss for long periods because of personal decisions and were not included in our previous analyses, while some maintained SVR. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to determine the outcomes and related factors in patients with HBeAg-positive CHB with HBeAg loss [without hepatitis B e antibody (HBeAb)] after NAs cessation.

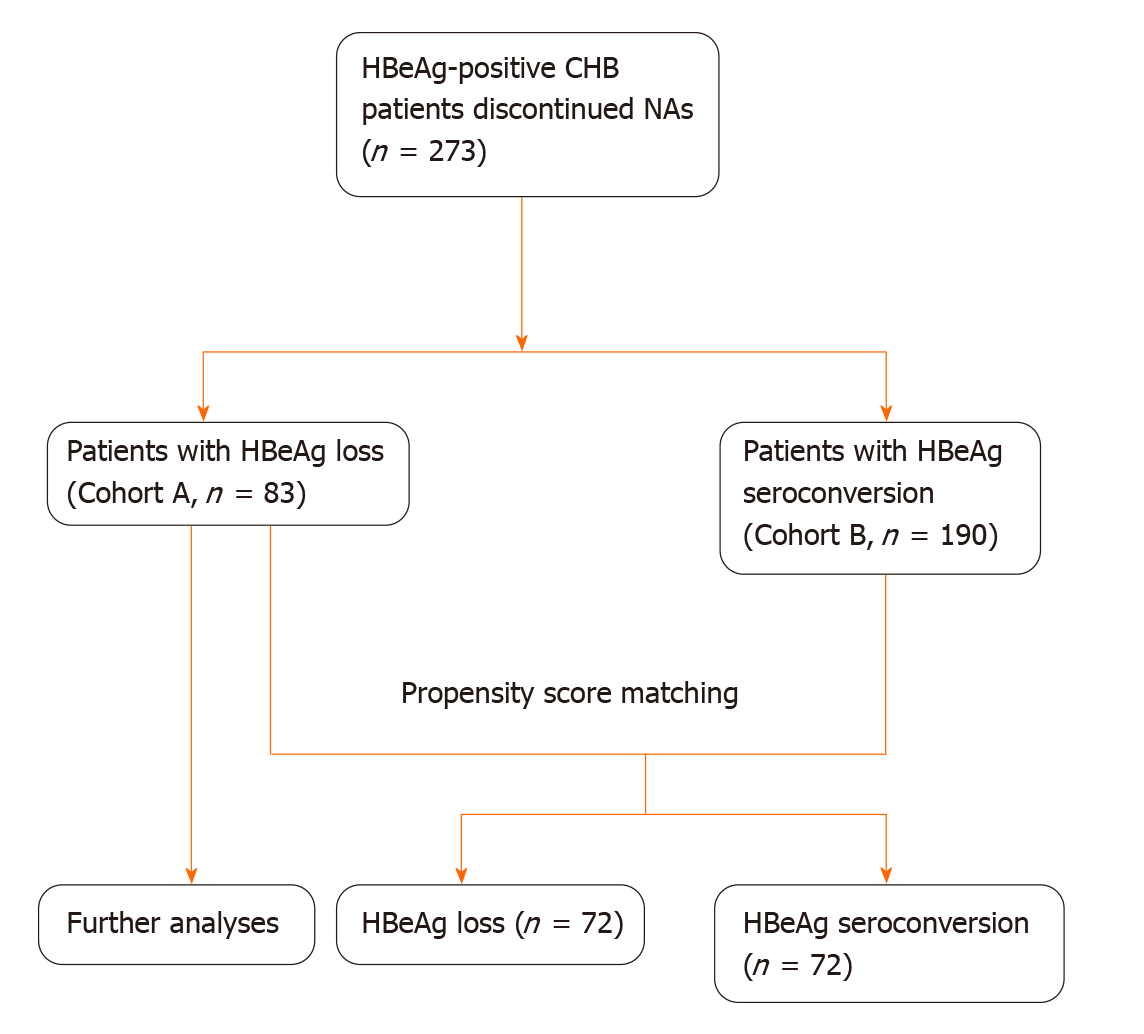

Patients: In our previous observational cohort, including CHB patients who discontinued NAs therapy and underwent regular follow-up, some discontinued NAs after achieving HBeAg loss (without HBeAb) for long periods. We included them in the current study (Cohort A). Before the decision to discontinue NAs, we informed all patients of the current guidelines, and we carefully evaluated all patients for potential risks. The patients decided to discontinue NAs according to their values and the state of their illness. We closely monitored them during follow-up after NAs cessation. Cumulative relapse rates were compared between HBeAg-positive patients with CHB who achieved HBeAg seroconversion (Cohort B) and Cohort A. Figure 1 describes the flowchart of patient inclusion. We recruited all patients from The Second Hospital, Cheeloo College of Medicine, Shandong University, between December 2001 and January 2020. All patients provided written informed consent. The Ethical Committee of The Second Hospital, Cheeloo College of Medicine, Shandong University, approved the study protocol. The study followed the principles of the Helsinki Declaration.

We previously published treatment criteria for NAs[5]. Cessation criteria required that patients in Cohort A receive at least 6 mo consolidation therapy after achieving HBeAg loss, with undetectable HBV DNA and normal alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and total therapy duration should last at least 18 mo. Patients in Cohort B should receive at least 6 mo consolidation therapy after achieving HBeAg seroconversion, with undetectable HBV DNA and normal ALT, and total therapy duration should be at least 12 mo. As per updated guidelines, consolidation therapy in these groups extended to at least 12 mo.

Exclusion criteria were signs of cirrhosis or decompensated liver disease and NAs resistance.

We retrospectively collected pretreatment baseline data. After NAs cessation, the patients were followed-up at months 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 9, and 12, and every 6 mo thereafter. The follow-up evaluation included liver biochemistry, serology of HBV, and quantification of HBV DNA.

The current study's observational endpoint was virological relapse, which was defined as serum HBV DNA > 104 copies/mL after NAs cessation confirmed 2 wk apart.

Variables were expressed as mean ± SD, median [interquartile range (IQR)], or number (percent) and were compared using the t-test, Mann–Whitney U test, chi-squared test, or Fisher's exact test. Cox proportional hazards model was used to identify predictors for response status after NAs cessation. The cut-off value of the consolidation period was confirmed using receiver operating characteristic curves; we confirmed the cut-off value of HBsAg according to a previous study[15]. The log-rank test was performed to compare cumulative relapse rates across groups. Propensity score matching (PSM) analysis was used to balance baseline characteristics between patients with HBeAg loss (Cohort A) and HBeAg seroconversion (Cohort B). We used 1:1 nearest-neighbor matching and a match tolerance of 0.10. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). The statistical procedure was reviewed by a biomedical statistician (Zhang Y).

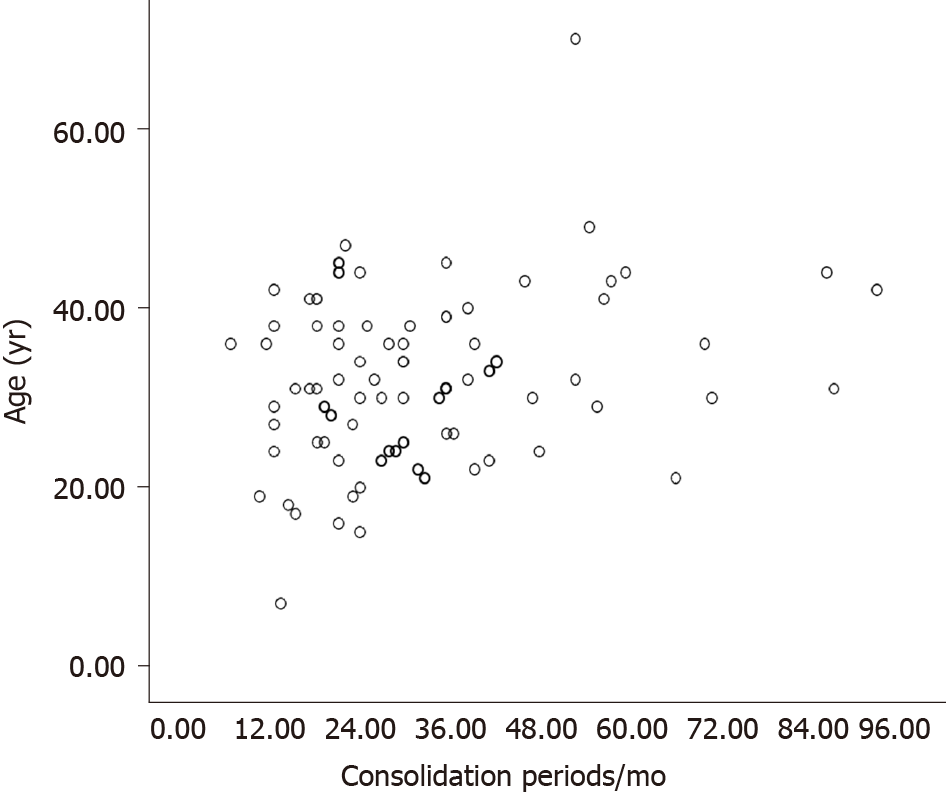

There were 83 patients in Cohort A. The mean age of these patients was 32.1 ± 9.5 years, and the majority was male (56 patients, 67.5%). We treated patients for a median of 49 (IQR 36–61) mo. The median follow-up period for patients with SVR was 72 (IQR 36–108) mo. Patients received single NAs, including lamivudine in 45 patients, adefovir dipivoxil in 24 patients, telbivudine in nine patients, entecavir in four patients, and tenofovir in one patient. Table 1 displays the baseline characteristics of the patients. Figure 2 describes the distribution of ages and consolidation periods.

| Total (n = 83) | Relapser (n = 38) | Non-relapser (n = 45) | P values2 | |

| Age at cessation (yr) | 32.1 ± 9.5 | 33.5 ± 9.8 | 31.0 ± 9.3 | 0.232 |

| Male, n (%) | 56 (67.5) | 24 (63.2) | 32 (71.1) | 0.441 |

| HBsAg < 100 IU/mL, n (%) | 19 (22.9) | 1 (2.6) | 18 (40.0) | < 0.001 |

| Pretreatment HBV DNA (log10 copies/mL)1 | 7.17 (6.71-7.68) | 7.29 (6.93-7.69) | 7.00 (6.10-7.68) | 0.123 |

| Total treatment period (mo)1 | 49 (36-61) | 50 (36-63) | 49 (37-61) | 0.876 |

| Pretreatment ALT1 | 151 (115-287) | 149 (118-256) | 163 (112 -305) | 0.721 |

| Pretreatment AST1 | 103 (68-180) | 105 (69 -181) | 102 (68 -169) | 0.927 |

| HBV DNA negativity last time (mo)1 | 44 (33-58) | 44 (33-60) | 44 (34-57) | 0.964 |

| Time to HBeAg loss (mo)1 | 14 (6-31) | 19 (9-33) | 12 (6-30) | 0.241 |

| Consolidation periods (mo)1 | 28 (19-40) | 23 (18-38) | 30 (21-40) | 0.102 |

Thirty-eight patients relapsed and the cumulative relapse rates at month 3, 6, 12, 24, 36, 60, 120, and 180 were 22.9%, 36.1%, 41.0%, 43.5%, 45.0%, 45.0%, 45.0%, and 52.8%, respectively. Twenty-six (68.4%) patients relapsed in the first 3 mo after NAs cessation, and 35 patients (92.1%) relapsed in the first year after NAs cessation. The latest relapse occurred at month 129 after NAs cessation. Table 1 displays the baseline characteristics of relapsed patients and patients with SVR. All relapsed patients received close follow-up or salvage treatments according to their condition and treatment history. No liver failure or hepatic decompensation occurred.

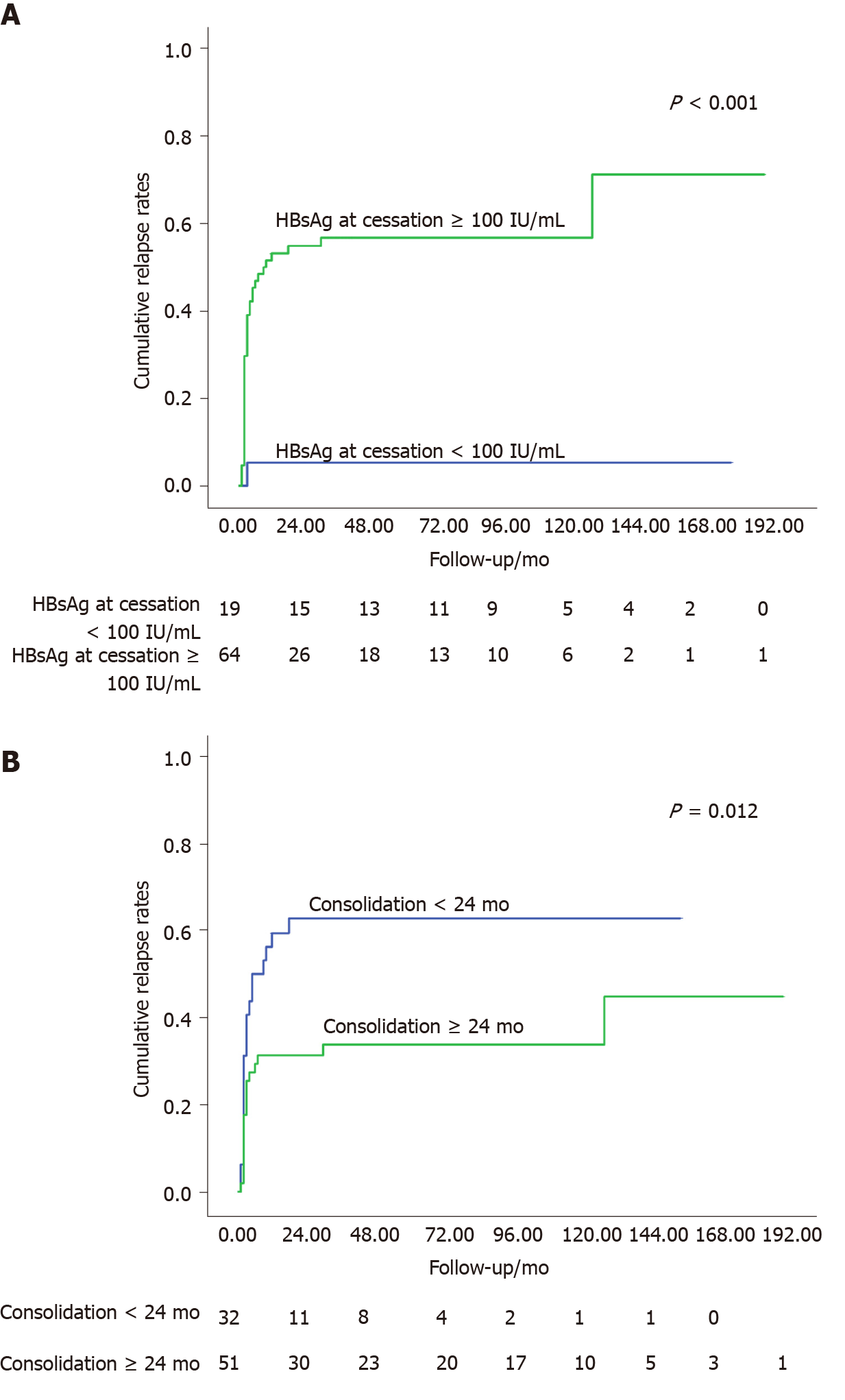

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression determined predictors for virological relapse. Only consolidation period (≥ 24 mo vs < 24 mo) (HR 0.506, P = 0.043) and HBsAg at cessation (≥ 100 IU/mL vs < 100 IU/mL) (HR 14.869, P = 0.008) were significant predictors in multivariate regression (Table 2).

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

| HR | 95%CI | P values | HR | 95%CI | P values | |

| Age at cessation | 1.021 | 0.987-1.056 | 0.235 | |||

| Gender | 0.783 | 0.405-1.515 | 0.468 | |||

| Pretreatment ALT | 0.999 | 0.998-1.001 | 0.451 | |||

| Pretreatment AST | 1.000 | 0.997-1.002 | 0.716 | |||

| Pretreatment HBV DNA (log10 copies/mL) | 1.391 | 0.942-2.054 | 0.097 | 1.256 | 0.816-1.933 | 0.300 |

| Total treatment duration | 1.001 | 0.989-1.013 | 0.826 | |||

| HBV DNA negativity last time | 1.001 | 0.988-1.013 | 0.915 | |||

| Consolidation periods (≥ 24 mo vs < 24 mo) | 0.469 | 0.247-0.891 | 0.021 | 0.506 | 0.262-0.978 | 0.043 |

| HBsAg at cessation (≥ 100 IU/mL vs < 100 IU/mL) | 15.515 | 2.119-113.575 | 0.007 | 14.869 | 2.027-109.084 | 0.008 |

Among the 19 patients with HBsAg at cessation < 100 IU/mL, only one patient relapsed at month 3 after NAs cessation, and the cumulative relapse rates were significantly lower than those of patients with HBsAg at cessation ≥ 100 IU/mL (log-rank test, P < 0.001, Figure 3A). For the 51 patients with longer consolidation periods (≥ 24 mo), the cumulative relapse rates at month 3, 6, 12, 24, 36, 60, 120, and 180 were 17.6%, 27.5%, 31.4%, 31.4%, 33.8%, 33.8%, 33.8%, and 44.9%, respectively, which maintained significantly lower relapse rates than patients with shorter consolidation periods (< 24 mo) (log-rank test, P = 0.012, Figure 3B).

Six of 83 patients achieved functional cure (HBsAg loss) at cessation. All these patients maintained SVR and HBsAg loss during follow-up. The other 11 patients, although they had detectable HBsAg at cessation, also achieved HBsAg loss during follow-up after cessation and maintained SVR. The median follow-up period of these 11 patients was 108 (IQR 78–180) mo.

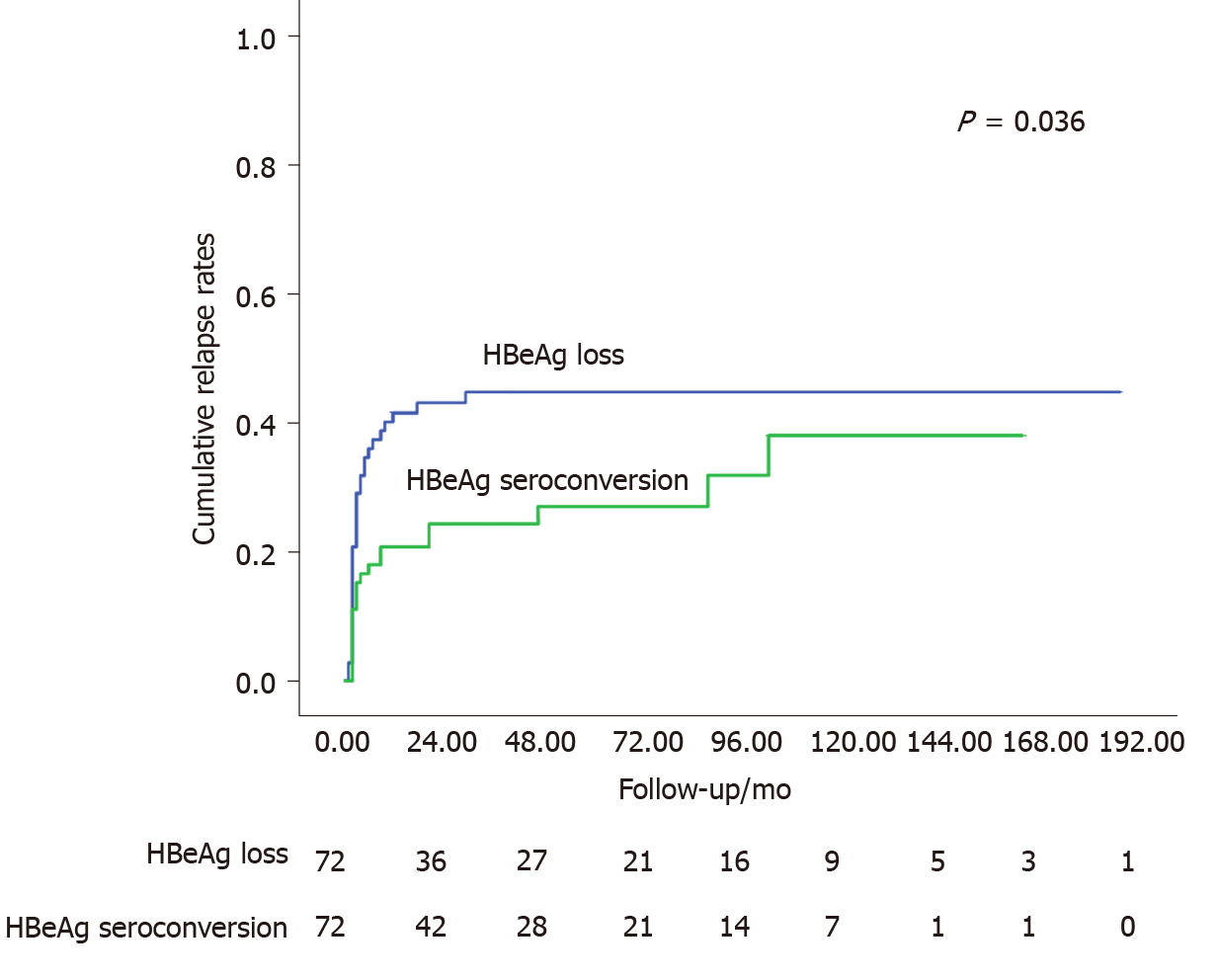

We preliminarily screened 83 patients in Cohort A and 190 patients in Cohort B for PSM. We included 144 patients (72 pairs) in the PSM cohort (Figure 1). The baseline characteristics remained comparable between the two groups (Table 3). The log-rank test revealed lower cumulative relapse rates in patients with HBeAg seroconversion (P = 0.036, Figure 4).

| HBeAg loss (n = 72) | HBeAg seroconversion (n = 72) | P values2 | |

| Age at cessation (yr) | 31.8 ± 10.0 | 31.5 ± 11.8 | 0.873 |

| Male, n (%) | 49 (68.1) | 48 (66.7) | 0.859 |

| Functional cure, n (%) | 15 (20.8) | 8 (11.1) | 0.111 |

| Pretreatment HBV DNA (log10 copies/mL)1 | 7.14 (6.70-7.65) | 7.00 (6.67-7.67) | 0.781 |

| Pretreatment ALT1 | 151 (114-287) | 200 (117-301) | 0.394 |

| Pretreatment AST1 | 102 (69 -188) | 122 (72 -204) | 0.327 |

| Consolidation periods (mo)1 | 28 (21-40) | 23 (15-37) | 0.065 |

| Time to HBeAg loss/conversion1 | 12 (6-25) | 15 (7-27) | 0.566 |

The response status of patients with HBeAg-positive CHB with HBeAg loss after NAs cessation was evaluated. Despite the absence of HBeAb, these patients maintained acceptable virological response after relatively long-term consolidation therapy, especially in patients with HBsAg at cessation < 100 IU/mL. After PSM, the cumulative relapse rates were higher than those in patients with HBeAg seroconversion. More extended consolidation periods (≥ 24 mo) and low HBsAg at cessation (< 100 IU/mL) predicted better response after NAs cessation.

NAs cessation remains a matter of debate in clinical practice. Although a functional cure has been recognized as a feasible goal and an acknowledged treatment endpoint of NAs therapy[12,16,17], the low incidence rates are an essential obstacle to its clinical application. Furthermore, a considerable proportion of HBeAg-positive patients with CHB stopped NAs before achieving HBsAg loss; nevertheless, the response status remained acceptable[5,14]. For these reasons, NAs cessation following HBeAg seroconversion plus more than 1–3-year consolidation therapy is recommended by current guidelines for HBeAg-positive patients with CHB[1-3]. Because some patients in our cohort discontinued NAs after achieving HBeAg loss (without HBeAb) for long periods, the current study compared cumulative relapse rates between CHB patients with HBeAg loss and those with HBeAg seroconversion. Although the cumulative relapse rates remained acceptable in patients with HBeAg loss (45.0% at year 10), better outcomes were observed in patients with HBeAg seroconversion.

To achieve better outcomes for CHB patients with HBeAg loss, we recommend sufficient consolidation periods. In the present study, the consolidation period (≥ 24 mo) was considered an independent predictor for SVR. There were similar conclusions in previous studies exploring factors predicting drug withdrawal for patients with CHB achieving HBeAg seroconversion[5,10,18-21]. Nevertheless, the consolidation periods remain controversial. The three cut-off values (12 mo, 18 mo, and 36 mo) adopted by different cohorts might be attributed to various sample size distributions in different consolidation periods. In the current study, more than one-third of patients received consolidation for more than 36 mo (Figure 2), which ensured the cut-off value's credibility (≥ 24 mo). In addition, according to recommendations of early guidelines, three patients in Cohort A discontinued NAs with consolidation periods less than 12 mo. All these patients relapsed and were re-treated with good outcomes.

In addition to lengthier consolidation, several other factors in Cohort A patients may help obtain better outcomes. As mentioned above, HBsAg is an essential predictor of response status after NAs cessation[15]. Lower HBsAg at cessation predicted better outcomes[15], and our present results corroborate this finding. In Cohort A, seventeen patients achieved HBsAg loss (six patients at cessation and another 11 patients during follow-up) in the present study, a relatively high percentage (20.5%). All these patients maintained HBsAg loss and SVR during follow-up. Second, younger age predicted SVR in both HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative CHB patients[5,10,13,22,23]. However, age was not a predictor in the current study. The mean age of the patients in Cohort A was 32.1 ± 9.5 years, a relatively young sample. Furthermore, 82 patients (98.8%) were under 50 years old, while 65 patients (78.3%) were under 40 years old (Figure 2). The narrow age spectrum may also conceal the role of age in prognosis after cessation. Third, we excluded patients with cirrhosis and decompensated liver disease. The current guidelines recommend indefinite antiviral therapy for these patients[1-3]. We also excluded patients with NAs resistance to obtain better outcomes.

We followed patients in the current study regularly to identify relapse as early as possible. Most patients (92.1%) relapsed in the first year after NAs cessation, especially during the first 3 mo (68.4%), suggesting that more careful monitoring is critical in the early stages after cessation. These characteristics were similar to those in patients achieving HBeAg seroconversion[5,14].

There are some limitations to the current study. First, most patients did not receive first-line NAs because of their enrollment in a relatively early period (since 2001), and we followed them for relatively long periods. We excluded patients with NAs resistance to minimize the influence of low-genetic barrier NAs. Second, as an exploratory study, some features of the included patients made them more likely to achieve a sustained response, which might decrease the representativeness of the current study.

In conclusion, HBeAg-positive CHB patients with HBeAg loss may be able to discontinue NAs therapy after long-term consolidation. HBsAg at cessation < 100 IU/mL predicts SVR after NAs cessation. Careful monitoring, especially in the early stages after cessation, should be adopted to ensure favorable outcomes

Nucleos(t)ide analogs (NAs) cessation in chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients remains a matter of debate in clinical practice, especially in patients who fail to achieve hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) seroconversion after the long-term loss of HBeAg. Few studies were explicitly designed for this subpopulation.

To determine whether chronic hepatitis B patients with HBeAg loss could discontinue NAs after long-term consolidation.

We investigated the outcomes and factors associated with HBeAg-positive CHB patients with HBeAg loss [without hepatitis B e antibody (HBeAb)] after cessation of NAs.

Patients who discontinued NAs after achieving HBeAg loss (without HBeAb) for long periods were included and predictive factors were explored. CHB patients who achieved HBeAg seroconversion were also included for controls.

HBeAg-positive CHB patients with HBeAg loss maintained acceptable virological response after NAs cessation, especially in patients with hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) at cessation < 100 IU/mL. After PSM, the cumulative relapse rates were higher than those in patients with HBeAg seroconversion. More extended consolidation periods (≥ 24 mo) and low HBsAg at cessation (< 100 IU/mL) predicted better response after NAs cessation.

HBeAg-positive CHB patients with HBeAg loss may be able to discontinue NAs therapy after long-term consolidation, especially in patients with HBsAg at cessation < 100 IU/mL.

HBeAg-positive CHB patients with HBeAg loss may be able to discontinue NAs therapy after long-term consolidation and lower HBsAg at cessation is preferred. Careful monitoring, especially in the early stages after cessation, may ensure a favorable outcome.

We thank Dr. Yuan Zhang for the statistical review of the study.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Castao YP, Naveed A, Popping S S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Terrault NA, Lok ASF, McMahon BJ, Chang KM, Hwang JP, Jonas MM, Brown RS Jr, Bzowej NH, Wong JB. Update on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 hepatitis B guidance. Hepatology. 2018;67:1560-1599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2290] [Cited by in RCA: 2827] [Article Influence: 403.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL 2017 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2017;67:370-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3745] [Cited by in RCA: 3779] [Article Influence: 472.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Sarin SK, Kumar M, Lau GK, Abbas Z, Chan HL, Chen CJ, Chen DS, Chen HL, Chen PJ, Chien RN, Dokmeci AK, Gane E, Hou JL, Jafri W, Jia J, Kim JH, Lai CL, Lee HC, Lim SG, Liu CJ, Locarnini S, Al Mahtab M, Mohamed R, Omata M, Park J, Piratvisuth T, Sharma BC, Sollano J, Wang FS, Wei L, Yuen MF, Zheng SS, Kao JH. Asian-Pacific clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatitis B: a 2015 update. Hepatol Int. 2016;10:1-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1985] [Cited by in RCA: 1951] [Article Influence: 216.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Papatheodoridi M, Papatheodoridis G. Emerging Diagnostic Tools to Decide When to Discontinue Nucleos(t)ide Analogues in Chronic Hepatitis B. Cells. 2020;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Liu F, Liu ZR, Li T, Liu Y, Zhang M, Xue Y, Zhang LX, Ye Q, Fan XP, Wang L. Varying 10-year off-treatment responses to nucleos(t)ide analogues in patients with chronic hepatitis B according to their pretreatment hepatitis B e antigen status. J Dig Dis. 2018;19:561-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yip TC, Lok AS. How Do We Determine Whether a Functional Cure for HBV Infection Has Been Achieved? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:548-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kadelka S, Ciupe SM. Mathematical investigation of HBeAg seroclearance. Math Biosci Eng. 2019;16:7616-7658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Milich DR. Is the function of the HBeAg really unknown? Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15:2187-2191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Damiris K, Tafesh ZH, Pyrsopoulos N. Efficacy and safety of anti-hepatic fibrosis drugs. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:6304-6321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 10. | Lee HW, Lee HJ, Hwang JS, Sohn JH, Jang JY, Han KJ, Park JY, Kim DY, Ahn SH, Paik YH, Lee CK, Lee KS, Chon CY, Han KH. Lamivudine maintenance beyond one year after HBeAg seroconversion is a major factor for sustained virologic response in HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2010;51:415-421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Terrault NA, Bzowej NH, Chang KM, Hwang JP, Jonas MM, Murad MH; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. AASLD guidelines for treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2016;63:261-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1532] [Cited by in RCA: 1581] [Article Influence: 175.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 12. | Cornberg M, Lok AS, Terrault NA, Zoulim F; 2019 EASL-AASLD HBV Treatment Endpoints Conference Faculty. Guidance for design and endpoints of clinical trials in chronic hepatitis B - Report from the 2019 EASL-AASLD HBV Treatment Endpoints Conference‡. J Hepatol. 2020;72:539-557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 47.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sohn HR, Min BY, Song JC, Seong MH, Lee SS, Jang ES, Shin CM, Park YS, Hwang JH, Jeong SH, Kim N, Lee DH, Kim JW. Off-treatment virologic relapse and outcomes of re-treatment in chronic hepatitis B patients who achieved complete viral suppression with oral nucleos(t)ide analogs. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wang L, Liu F, Liu YD, Li XY, Wang JB, Zhang ZH, Wang YZ. Stringent cessation criterion results in better durability of lamivudine treatment: a prospective clinical study in hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B patients. J Viral Hepat. 2010;17:298-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Liu J, Li T, Zhang L, Xu A. The Role of Hepatitis B Surface Antigen in Nucleos(t)ide Analogues Cessation Among Asian Patients With Chronic Hepatitis B: A Systematic Review. Hepatology. 2019;70:1045-1055. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lok AS, Zoulim F, Dusheiko G, Ghany MG. Hepatitis B cure: From discovery to regulatory approval. Hepatology. 2017;66:1296-1313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 247] [Cited by in RCA: 245] [Article Influence: 30.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Alawad AS, Auh S, Suarez D, Ghany MG. Durability of Spontaneous and Treatment-Related Loss of Hepatitis B s Antigen. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020; 18: 700-709. e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chi H, Hansen BE, Yim C, Arends P, Abu-Amara M, van der Eijk AA, Feld JJ, de Knegt RJ, Wong DK, Janssen HL. Reduced risk of relapse after long-term nucleos(t)ide analogue consolidation therapy for chronic hepatitis B. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:867-876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Dai CY, Tseng TC, Wong GL, Huang JF, Wong VW, Liu CJ, Yu ML, Chuang WL, Kao JH, Chan HL, Chen DS. Consolidation therapy for HBeAg-positive Asian chronic hepatitis B patients receiving lamivudine treatment: a multicentre study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68:2332-2338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kuo YH, Chen CH, Wang JH, Hung CH, Tseng PL, Lu SN, Changchien CS, Lee CM. Extended lamivudine consolidation therapy in hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B patients improves sustained hepatitis B e antigen seroconversion. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:75-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Jun BG, Lee SH, Kim HS, Kim SG, Kim YS, Kim BS, Jeong SW, Jang JY, Kim YD, Cheon GJ. Predictive Factors for Sustained Remission after Discontinuation of Antiviral Therapy in Patients with HBeAg-positive Chronic Hepatitis B. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2016;67:28-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Liu F, Wang L, Li XY, Liu YD, Wang JB, Zhang ZH, Wang YZ. Poor durability of lamivudine effectiveness despite stringent cessation criteria: a prospective clinical study in hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:456-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chen CH, Hung CH, Hu TH, Wang JH, Lu SN, Su PF, Lee CM. Association Between Level of Hepatitis B Surface Antigen and Relapse After Entecavir Therapy for Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 13: 1984-92. e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |