Published online Mar 28, 2021. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i12.1213

Peer-review started: November 28, 2020

First decision: December 24, 2020

Revised: January 7, 2021

Accepted: March 12, 2021

Article in press: March 12, 2021

Published online: March 28, 2021

Processing time: 113 Days and 12.5 Hours

We recently demonstrated that the odds of contracting coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in patients with celiac disease (CeD) is similar to that of the general population. However, how patients with CeD perceive their COVID-19 risk may differ from their actual risk.

To investigate risk perceptions of contracting COVID-19 in patients with CeD and determine the factors that may influence their perception.

We distributed a survey throughout 10 countries between March and June 2020 and collected data on demographics, diet, COVID-19 testing, and risk perceptions of COVID-19 in patients with CeD. Participants were recruited through various celiac associations, clinic visits, and social media. Risk perception was assessed by asking individuals whether they believe patients with CeD are at an increased risk of contracting COVID-19 when compared to the general population. Logistic regression was used to determine the influencing factors associated with COVID-19 risk perception, such as age, sex, adherence to a gluten-free diet (GFD), and comorbidities such as cardiac conditions, respiratory conditions, and diabetes. Data was presented as adjusted odds ratios (aORs)

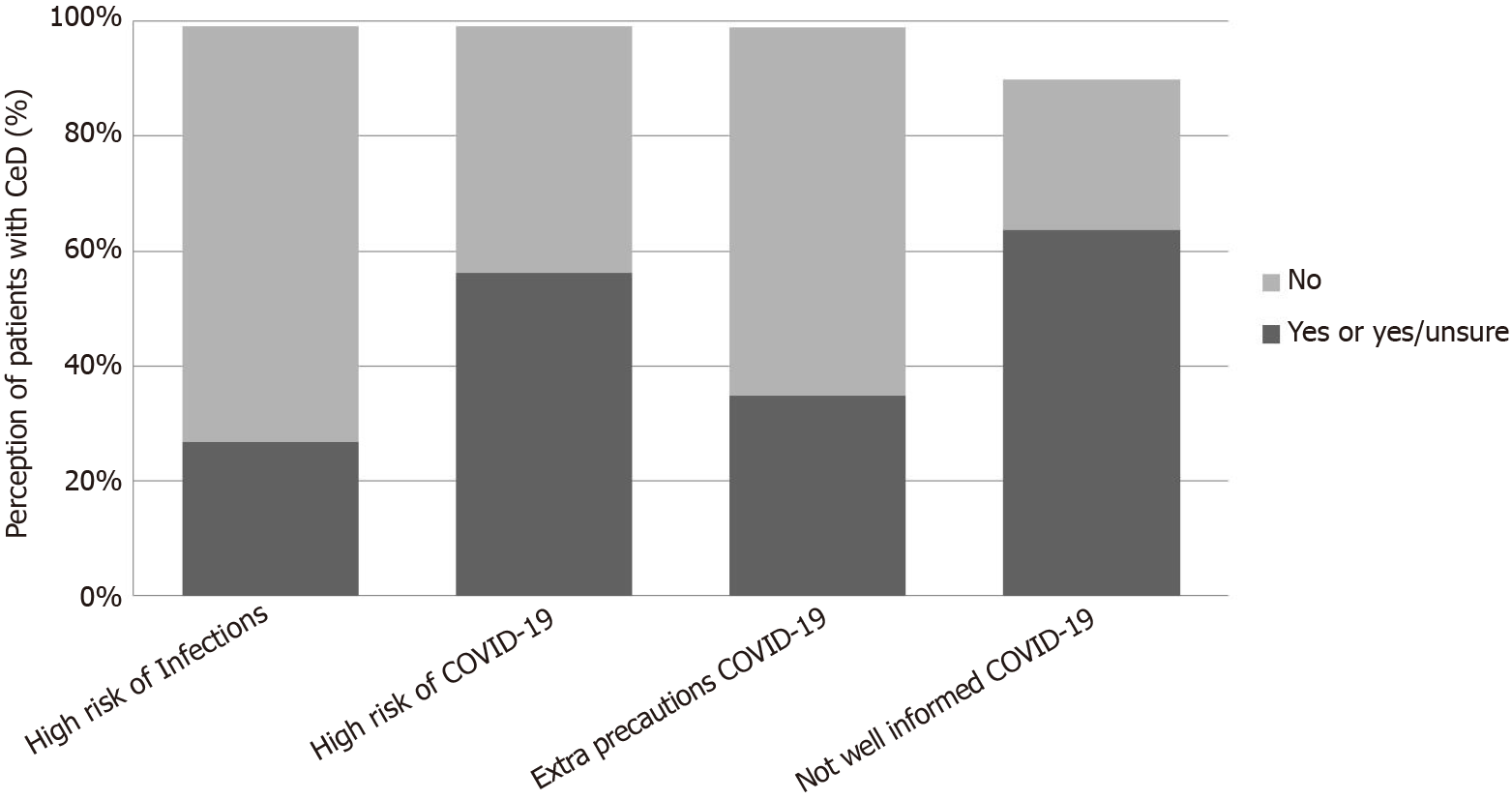

A total of 10737 participants with CeD completed the survey. From them, 6019 (56.1%) patients with CeD perceived they were at a higher risk or were unsure if they were at a higher risk of contracting COVID-19 compared to the non-CeD population. A greater proportion of patients with CeD perceived an increased risk of contracting COVID-19 when compared to infections in general due to their CeD (56.1% vs 26.7%, P < 0.0001). Consequently, 34.8% reported taking extra COVID-19 precautions as a result of their CeD. Members of celiac associations were less likely to perceive an increased risk of COVID-19 when compared to non-members (49.5% vs 57.4%, P < 0.0001). Older age (aOR: 0.99; 95%CI: 0.99 to 0.99, P < 0.001), male sex (aOR: 0.84; 95%CI: 0.76 to 0.93, P = 0.001), and strict adherence to a GFD (aOR: 0.89; 95%CI: 0.82 to 0.96, P = 0.007) were associated with a lower perception of COVID-19 risk and the presence of comorbidities was associated with a higher perception of COVID-19 risk (aOR: 1.38; 95%CI: 1.22 to 1.54, P < 0.001).

Overall, high levels of risk perceptions, such as those found in patients with CeD, may increase an individual’s pandemic-related stress and contribute to negative mental health consequences. Therefore, it is encouraged that public health officials maintain consistent communication with the public and healthcare providers with the celiac community. Future studies specifically evaluating mental health in CeD could help determine the consequences of increased risk perceptions in this population.

Core Tip: Risk perceptions describe an individual’s perceived susceptibility to a threat and directly influence their behavior. We conducted an international cross-sectional study to evaluate risk of contracting contracting coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in celiac disease and evaluated risk perception. Patients with celiac disease perceive they are at an increased risk of contracting COVID-19 due to their condition, which is opposite to current scientific evidence. A higher risk perception may have a negative impact in mental health, and therefore, we encourage healthcare providers, patient care groups, and public health officials to discuss the implications that COVID-19 may have on patients in relation to their specific conditions.

- Citation: Zhen J, Stefanolo JP, Temprano MLP, Seiler CL, Caminero A, de-Madaria E, Huguet MM, Santiago V, Niveloni SI, Smecuol EG, Dominguez LU, Trucco E, Lopez V, Olano C, Mansueto P, Carroccio A, Green PH, Duerksen D, Day AS, Tye-Din JA, Bai JC, Ciacci C, Verdú EF, Lebwohl B, Pinto-Sanchez MI. Risk perception and knowledge of COVID-19 in patients with celiac disease. World J Gastroenterol 2021; 27(12): 1213-1225

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v27/i12/1213.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v27.i12.1213

Coronaviruses, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus and middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus which arose in 2003 and 2012, respectively, represent a family of positive-stranded RNA viruses that infect the respiratory system[1]. Later, the Chinese city of Wuhan reported an outbreak of a novel infectious agent causing severe cases of pneumonia and alerted the World Health Organization (WHO) of its presence on December 31, 2019[2]. The disease caused by this infectious agent was later named coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Since the WHO declared COVID-19 a global pandemic in March 2020, there has been over 105 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 across 216 countries and territories and the disease has killed over 2300000 people worldwide[3].

Due to the rapid spread and detrimental health consequences of COVID-19, there is an urgent need to determine which groups of individuals may have an increased susceptibility to infection and understand the perceptions they have regarding their susceptibility. A particular group of interest are patients with celiac disease (CeD), a chronic immune-mediated gastrointestinal disease that is triggered by dietary gluten intake in genetically predisposed individuals. Numerous studies suggest that CeD is associated with an increased risk of respiratory infections, particularly pneumonia, tuberculosis, and influenza[4-6]. However, we have shown that the odds of contracting COVID-19 in patients with CeD is similar to that of the general population[7].

As a result of the discrepancies between the risks of contracting different infections in patients with CeD, patient-specific risk perceptions of COVID-19 are of particular interest. Risk perceptions describe an individual’s perceived susceptibility to a threat and directly influence their health behaviors[8-10]. Further, risk perception is a complex, psychological construct that varies markedly between individuals and is influenced by their emotional, social, cultural, geographical, and cognitive state[11].

The concept of risk perception is especially important in the context of a pandemic because a group’s perception of their susceptibility to infection influences their willingness to cooperate with and adopt preventative safety measures such as travel restrictions, hand washing, social distancing, and personal protective equipment (PPE) use[11]. Although strict implementation of infection control measures, such as social distancing, can reduce infection rate, they may also increase the risk for mental health conditions[12]. These mental health risks are even more likely to occur in individuals who are or believe they are more vulnerable to COVID-19[13]. Patients with CeD, especially those with a higher risk perception, may be more vulnerable to the negative mental health consequences of COVID-19 due to the high rates of mood disorders commonly associated with CeD[14]. However, studies of risk perception in patients with CeD have been limited to an Italian study of 276 patients which found that 26.1% of their patients either felt neutral or felt they were at an increased risk of COVID-19 because of their CeD[15].

To validate and explore this further, we conducted an international, cross-sectional survey investigating the COVID-19 risk perceptions of patients with a self-reported diagnosis of CeD and examined the factors that may influence their perceptions.

The study was approved by the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (Hamilton, Ontario), No. HIREB# 5414. The methods of this study were previously described[8].

This observational, cross-sectional study included participants of all ages with a self-reported diagnosis of CeD and non-celiac population residing in either Argentina, Australia, Canada, Italy, Mexico, New Zealand, Spain, Uruguay, or the United States. The survey was open to participants from other countries, but extensive distribution of the survey was limited to the above-mentioned countries.

We designed a web-based survey consisting of 41 items. Participants were offered a different link to the survey depending on whether they reported a diagnosis of CeD or not. The study questionnaire was divided into specific sections to capture information on their demographics, adherence to a gluten-free diet (GFD), symptomatology, comorbidities, medications, COVID-19 testing, and patient knowledge/perception of the relationship between COVID-19 and CeD[16]. Individuals who believed they were at an increased risk or were unsure if they are at an increased risk of contracting COVID-19 due to their CeD were considered to have high COVID-19 risk perceptions. Patient knowledge and perception was only assessed in the CeD population. After piloting and testing by the authors, the English survey was placed into the secure online electronic case report platform, Research Electronic Data capture[17], and later translated into Italian and Spanish by the authors. We further collected information on country-specific COVID-19 control and safety measures implemented during the study period.

Participants were recruited from March 2020 to June 2020. Recruitment of self-reported CeD patients was performed through national celiac associations (via electronic newsletter and social media) and at clinic visits.

Statistical analyses were carried out using IBM-SPSS (IBM-SPSS Inc, Version 25.0, Armonk, NY, United States) and STATA (Stata version 13.0 Corp, College Station, TX, United States). Graphics were created using Microsoft Excel and GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Version 8.4 San Diego, CA, United States). Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages, whereas continuous variables were reported as mean (SD) or median and interquartile range when applicable. Comparisons of categorical variables between groups were performed using χ2 test. Haldane corrections were applied to χ2 tests when necessary. A two-sided test was used and P values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Logistic regression was used to assess the predictors of high COVID-19 risk perceptions. The model included COVID-19 risk perception as a dependent variable and factors including age, sex, adherence to a GFD, comorbidities, and use of corticosteroids, as independent variables.

Overall, out of the 18022 participants who completed the survey, 10737 participants self-reported a diagnosis of CeD. The demographics for the included population can be found in Table 1. Missing data constituted less than 3% for each variable and thus were not replaced.

| Demographic | CeD, n = 10737 |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 41 (28-57) |

| Gender, n (%) | 10646 (99.2) |

| Male | 1575 (14.8) |

| Female | 9017 (84.7) |

| CeD diagnosis, n (%) | 10570 (98.4) |

| Bloodwork1 | 1304 (12.1) |

| Biopsy | 1334 (12.4) |

| Bloodwork + biopsy | 7506 (69.9) |

| Unsure | 426 (4.0) |

| Years since diagnosis, median (IQR) | 7 (3-13) |

| Member of celiac association, n (%) | 2766 (25.8) |

| Diet, n (%) | |

| Unrestricted | 61 (0.6) |

| Other restrictions-non gluten | 29 (0.3) |

| GFD-sometimes | 118 (1.1) |

| GFD-most of the time | 283 (2.6) |

| GFD-rare intentional gluten | 418 (3.9) |

| GFD-rare accidental gluten | 1566 (14.6) |

| GFD-possible cross-contamination | 1136 (10.6) |

| Strict GFD | 7052 (65.7) |

| Years diet restriction, Median (IQR) | 7 (3-12) |

| Any household member following GFD, n (%) | 2688 (25.0) |

| Some members | 1949 (18.2) |

| All members | 409 (3.8) |

| Other | 221 (2.1) |

| Management of CeD symptoms, n (%) | |

| Well controlled | 7336 (68.3) |

| Symptoms < 2 mo | 2362 (22.0) |

| Symptoms > 2 mo | 938 (8.7) |

| Travel outside of the country2, n (%) | 202 (1.9) |

| Contact with COVID-19 positive, n (%) | 175 (1.6) |

| Tested for COVID-19, n (%) | 478 (4.5) |

| Fever2, n (%) | 252 (2.3) |

| Respiratory symptoms2, n (%) | 1124 (10.5) |

| Hospitalizations for respiratory infection2, n (%) | 21 (0.2) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |

| Chronic lung condition | 708 (6.6) |

| Chronic heart condition | 376 (3.5) |

| Diabetes | 413 (3.8) |

| Receiving steroids | 322 (3.0) |

| Receiving immune suppressive medications | 393 (3.7) |

| Pregnancy, n (%) | 96 (0.9) |

| Information about COVID-19 in celiac disease | |

| Internet | 2942 (27.4) |

| My doctor | 291 (2.7) |

| Other healthcare providers | 313 (2.9) |

| Celiac association website | 2465 (23.0) |

| Other | 731 (6.8) |

The median age of the participants was 41 years, of which 1575 (14.8%) were male. The highest proportions of respondents were from Argentina and Canada followed by Australia, New Zealand, and the United States. The detailed geographical distribution of participants by country, states, provinces and departments can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

The majority of self-reported patients with CeD had been diagnosed via CeD-specific serology [anti-tissue transglutaminase immunoglobulin (Ig) A and/or anti-deaminated gliadin peptide IgG] and confirmed via duodenal biopsy (n = 7506; 69.9%). The median time since diagnosis was 7 years. Out of all the participants with CeD, 25.8% were affiliated with a regional/national celiac association.

The majority of patients with CeD reported following a strict GFD (65.7%) with 33.4% adopting a GFD with some transgressions and 0.9% following a diet without gluten restriction. Of the patients following a GFD, the median time of gluten restriction was 7 years. Further, 24.1% of patients with CeD reported having household members who were also following a GFD. The majority of participants with CeD reported having their symptoms well-controlled (68.3%), while 31.7% had persistent symptoms.

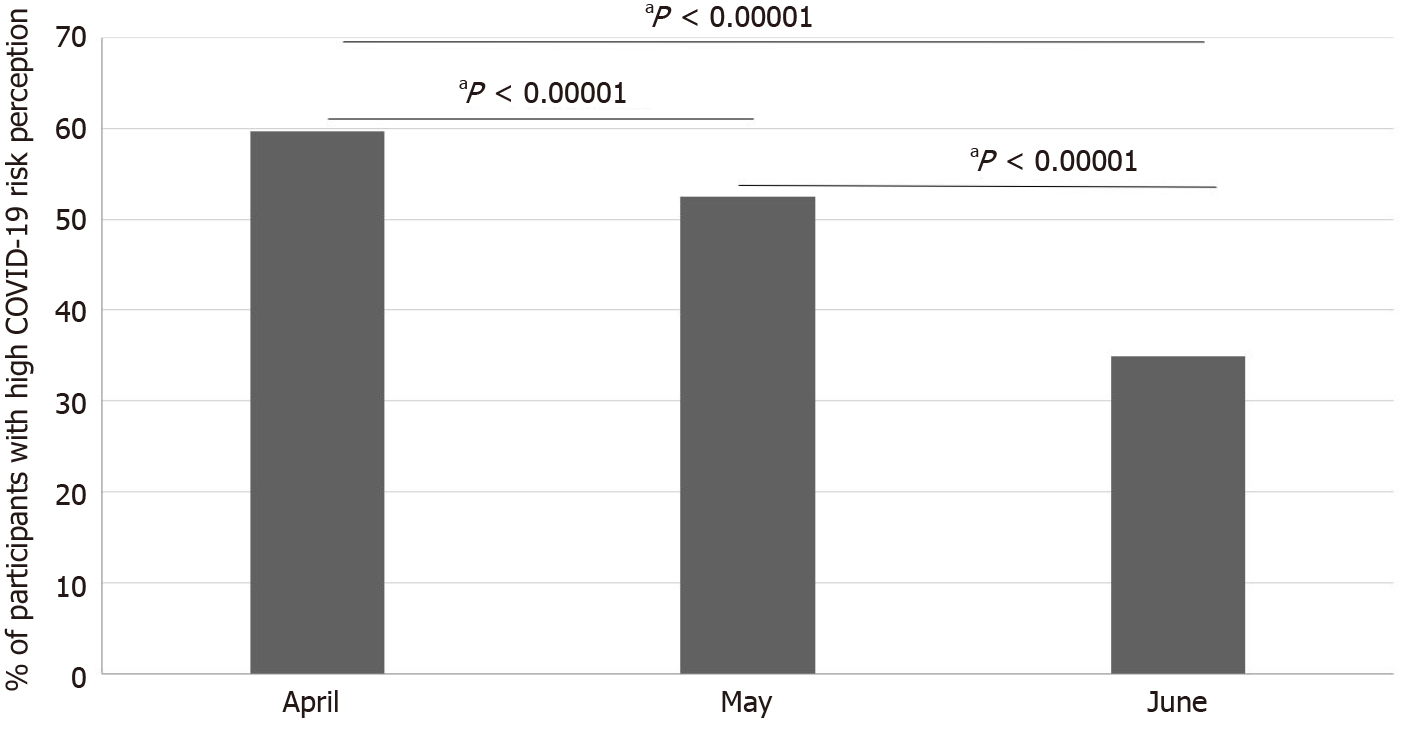

Patients with CeD obtained information about the relationship between COVID-19 and CeD through the internet (n = 2942; 27.4%) or through celiac association websites (n = 2465; 23%) (Table 1). Only a small proportion of patients reported learning through their physicians or other healthcare team members (n = 604; 5.6%). When asked to comment on their understanding regarding the relationship between COVID-19 and CeD, the majority of participants with CeD (n = 8815; 63.6%) reported that they did not have a very good understanding of their risk of contracting COVID-19 in relation to their condition. Consequently, 63.6% of patients requested more information on how COVID-19 may affect them. Further, while only 26.7% of participants with CeD believed they either were or were unsure whether they were more susceptible to infections because of their CeD, this proportion increased significantly when asked about their susceptibility to contracting COVID-19 in particular (26.7% vs 56.1%, P < 0.0001) (Figure 1). Participants who were members of their local celiac associations had lower rates of perceiving an increased risk of contracting COVID-19 compared to non-members (49.5% vs 57.4%, P < 0.0001) (Table 2). There was a stepwise decline in the proportion of patients with high-risk perceptions of contracting COVID-19 as the pandemic progressed (Figure 2).

| Member of a celiac association | CeD respondents, n = 7296 | Respondents with high COVID-19 risk perceptions | P value |

| Yes | 2766 | 1368 (49.5) | < 0.0001 |

| No | 4530 | 2600 (57.4) |

Country-specific COVID-19 risk perceptions were highest in the United States (73.1%), Australia (67.3%), New Zealand (65.0%), and Argentina (62.9%) and lowest in Spain (19.1%) and Uruguay (23.3%) (Table 3).

| Country | Infection rate1 | ORs for contracting COVID-19 (CeD vs controls) | 95%CI | CeD patients believing they are more susceptible to COVID-19, n (%) |

| Argentina | 0.14 | 1.41 | 0.48-4.12 | 2637 (62.9) |

| Canada | 0.04 | 0.80 | 0.31-2.01 | 1962 (52.1) |

| Australia | 0 | 1.92 | 0.03-99.21 | 449 (67.3) |

| New Zealand | 0 | 0.88 | 0.01-43.32 | 295 (65.0) |

| Spain | 0.21 | 0.73 | 0.21-2.57 | 85 (19.1) |

| United States | 0.16 | 3.28 | 0.61-17.44 | 304 (73.1) |

| Uruguay | 0 | 0.24 | 0.01-6.68 | 78 (23.3) |

| Italy | 0 | 0.27 | 0.01-6.37 | 85 (41.5) |

| Mexico | 0.6 | 1.50 | 0.15-14.42 | 62 (42.8) |

| Other2 | 0.17 | 0.70 | 0.08-6.22 | 62 (68.1) |

There were 3745 participants (34.8%) who reported that they were taking extra precautions for COVID-19 as a result of being diagnosed with CeD. The most common precautions included at least one of the following: Extensive isolation/social distancing (68.6%), extended PPE use (gloves, face masks) before widespread recommendations (32.7%), and consistent hand washing/sanitization (23.4%). Further infection control measures included paying extra attention to maintaining a GFD (6.1%), getting grocery/food delivery (2.9%), strict adherence to public health recommendations (2.4%), implementing vitamins, supplements, and healthy foods into their diet (2.0%), showering/washing clothes after returning home (1.4%), getting the influenza vaccine (0.8%), and one participant noted that they stopped their immunosuppressant medication use. Information on the country-specific infection control/safety measures implemented in the general population during the study period is shown in the Supplementary Material (Supplementary Table 2).

Older age [odds ratios (aORs): 0.99; 95%CI: 0.99 to 0.99, P < 0.001], male sex (aOR: 0.84; 95%CI: 0.76 to 0.93, P = 0.001), and adherence to a strict GFD (aOR: 0.89; 95%CI 0.82 to 0.96, P = 0.007) were associated with a lower perception of COVID-19 risk. However, the presence of comorbidities such as chronic lung conditions, chronic heart conditions (including hypertension), and diabetes, was associated with an increased perception of COVID-19 risk (aOR: 1.38; 95%CI: 1.22 to 1.54, P < 0.001). The use of corticosteroids or immunosuppressants did not change risk perception levels for contracting COVID-19 (aOR: 0.86; 95%CI: 0.68 to 1.08, P = 0.19) (Table 4).

| Risk perception | ||||

| Crude [OR (95%CI)] | P value | Adjusted1 [OR (95%CI)] | P value | |

| Older age | 0.99 (0.99-0.99) | 0.012 | 0.99 (0.99-0.99) | < 0.001 |

| Sex (M) | 0.84 (0.76-0.93) | 0.001 | 0.84 (0.75-0.93) | 0.001 |

| Strict GFD | 0.88 (0.81-0.95) | 0.002 | 0.89 (0.82-0.96) | 0.007 |

| Comorbidities2 | 1.29 (1.17-1.43) | < 0.001 | 1.37 (1.22-1.54) | < 0.001 |

| Use of corticosteroids or immunosuppressants | 1.11 (0.91-1.37) | 0.28 | 0.86 (0.68-1.08) | 0.19 |

This study included over 10500 CeD patients and to our knowledge, is the first large-scale, international study to examine COVID-19 risk perceptions in patients with CeD. Despite demonstrating that the odds of contracting COVID-19 in patients with CeD is similar to that of the non-CeD population in our previous study[7], the majority of patients with CeD either believed they were at an increased risk or were uncertain of whether they were at an increased risk of contracting COVID-19 when compared to the general population.

A significant number of patients (44.0%) reported that their knowledge of the relationship between COVID-19 and CeD is poor or very poor with the majority of patients requesting more information. Further, while many patients learn about COVID-19 and CeD through the internet, very few learn about the relationship from their healthcare team. This is consistent with previous studies on CeD suggesting that patients are dissatisfied with the information offered by their physicians and feel like their general knowledge about CeD is inadequate[18]. Accordingly, previous reports suggest that many physicians have inadequate knowledge/awareness of the features associated with CeD which consequently has a direct impact on their patients’ education regarding their condition[19,20]. As a result, while studies have demonstrated that CeD is associated with an increased risk of general infections, we found that only 26.7% of patients with CeD in our study believed they were at an increased risk. This supports the view that patients are generally uninformed about the potential consequences of CeD. This also represents a potential area for improvement as physicians and healthcare providers should be encouraged to thoroughly discuss the implications of COVID-19 in relation to their patients’ conditions based on the emerging evidence.

Patient perceptions are particularly relevant during the COVID-19 pandemic as high rates of depression and mood disorders have been associated with patients with higher risk perceptions of COVID-19[21]. Notably, in contrast to the generally low risk-perception that patients with CeD had regarding infections overall, more than half of our participants with CeD perceived they were at an increased risk or were unsure whether they were at a higher risk of contracting COVID-19 compared to the general population. As there are major uncertainties related to the novel coronavirus, this drastically affects the ability to properly and accurately inform patients of its potential implications. A recent study identified the lack of information regarding the virus as one of the major elements that contribute to fear and its associated high risk perception related to COVID-19[22]. Conversely, the study conducted by Siniscalchi et al[15] in March 2020, found that the majority of their patients with CeD (56.6%) did not feel more vulnerable to COVID-19 due to their condition[15]. One potential consideration contributing to the discrepancy between our results could be related to differences in study populations, as their study was limited to an Italian population. However, our results show the same trend when the analysis is sub-grouped by country and demonstrated similar results within our Italian participants (Table 3). These results suggest that risk perceptions vary markedly depending on the geographical area of the participants, as suggested by others[11]. In particular, country-specific differences in risk perception may be attributed to a variety of factors such as differences in culture, political climate, government communication, phase/timing of the pandemic, country-specific impacts of COVID-19, rates of infection, testing amounts and indications, and infection control measures (Supplementary Table 2). Notably, patients with CeD from Spain and Uruguay were found to have generally low risk perceptions for COVID-19. This aligns with previous studies that have found that the impact of COVID-19 has been relatively small in Uruguay as a result of swift lockdowns[23] and that individuals from Spain have been noted to have low personal concern about COVID-19[24]. Additionally, as the time of data collection was early in the pandemic for the study conducted by Siniscalchi et al[15], it is possible that patient perceptions may have changed as the pandemic progressed. Our analysis of risk perceptions by month found a stepwise decline in the proportion of participants with high COVID-19 risk perceptions as the pandemic progressed. This may be a result of timing because later in the study period, many countries have already passed the first wave of the pandemic and it may be due to the release of information regarding the link between COVID-19 and CeD from national celiac associations later on in the pandemic. It is also possible that this could be a result from “COVID-19 fatigue” as people become less concerned and more inclined to return to normal life as they recognize that the pandemic will persist for long periods of time.

We further investigated the different factors that we anticipated may modify the odds of having high risk perceptions for contracting COVID-19 in patients with CeD. Our results demonstrate a small, although significant, association between both younger age and female sex with higher risk perceptions of contracting COVID-19. These results align with a study conducted by Rimal and Juon[25] which noted that younger, more educated individuals, have a higher risk perception of breast cancer. Further, our sex-specific findings are consistent with studies investigating both COVID-19 risk perceptions in the general population[11,26] and in patients with CeD[15].

Importantly, CeD has been associated with a large number of concomitant conditions such as cardiovascular conditions including hypertension, coronary artery disease, and arrhythmias, respiratory conditions such as asthma[27], and type 1 diabetes mellitus[28]. Further, it has been noted that the above-mentioned comorbidities may also predispose individuals to contracting COVID-19 and may contribute to a more severe disease course and mortality[29]. Accordingly, in our regression analysis, we noted that the presence of comorbidities such as chronic lung conditions, chronic heart conditions, and diabetes, increased the odds of patients believing they are at a higher risk of contracting COVID-19.

Notably, we found the use of corticosteroids or immunosuppressive therapies did not influence the odds of having high risk perceptions of COVID-19. This may potentially be attributed to nearly universal guidelines suggesting the continuation of immunosuppressive treatment during the pandemic and studies suggesting that the morbidity and mortality rates of patients who are immunosuppressed or have an autoimmune condition may be similar to that of the general population[30]. However, it is also possible that there was a selection bias if patients who perceived themselves to be at higher risk of contracting COVID-19 decided to stop the use of immuno-suppressive therapies; as expressed in a comment by one participant. It also is possible that this action was taken by other participants; however, this was not systematically investigated in our study. Further, while it has been hypothesized that patients with active CeD (unmanaged or incompletely managed) may be at an increased risk of infection, our results demonstrate that individuals who follow a strict GFD have lower odds of perceiving themselves to be at an increased risk of contracting COVID-19.

Overestimation of risk can lead to being overly anxious, overly cautious, negative mental and physical health consequences[8], and not visiting a healthcare provider even when they believe they should[15,31]. Studies investigating healthcare use during the COVID-19 pandemic found significant reductions in emergency department visits, hospital admissions, and non-urgent healthcare visits[32,33]. Researchers have suggested that this decrease may be due to a perceived fear of contracting COVID-19 in high-risk areas such as hospitals. As a result, virtual patient care has been rapidly adopted to minimize this risk. However, patients in low-resource areas, such as those without technology or internet, are unable to access these alternate forms of healthcare and may be unequally affected by the pandemic[34]. Therefore, the role of governmental and non-governmental organizations in promoting awareness and knowledge in underserved/underdeveloped communities is especially important during the current health crisis.

In our participants with CeD, we found that 34.8% were taking extra COVID-19 precautions as a result of their condition. Importantly, we found that patients who were members of national celiac associations had overall lower risk perceptions for contracting COVID-19. Nearly a quarter of our patients reported learning about the relationship between COVID-19 and CeD through celiac association websites, which are often responsible for distributing patient-centred educational resources[35]. Previous studies have suggested that membership in a patient association has been correlated to increased physical/psychological well-being and social adjustment[36]. As over 60% of our participants reported that they would like more information on how COVID-19 may affect patients with CeD patient associations, such as national celiac associations, represent a promising avenue to help effectively disseminate health information, educate patients, and encourage healthy social relationships.

We acknowledge the presence of limitations associated with our study. First, this study did not assess risk perceptions in the general population and in the CeD group, there may have been potential selection/referral bias towards patients belonging to celiac associations as these associations acted as our primary mode of recruitment. Further, the cross-sectional nature of this study design only allowed us to evaluate COVID-19 risk perceptions during our study period which may change over time. Therefore, future prospective longitudinal studies may help assess changes over different time periods of the pandemic. In addition, although we investigated several dimensions of risk perception, some potential factors were not assessed. For example, we did not assess risk perceptions related to mortality or concerns of infecting family and friends. We also did not assess the mental health outcomes related to high levels of risk perception. As a result, future studies investigating additional factors and potential mediators of COVID-19 risk perception in patients with CeD will inform physicians and celiac associations on how to best design and communicate risk mitigation strategies to support a potentially vulnerable patient population.

In conclusion, this international survey of patients with self-reported CeD demonstrates that a large proportion of patients with CeD perceive themselves to be at a high or unknown risk of contracting COVID-19. This association is more evident in females, those with comorbidities, and those who are not following a strict GFD. As a result of the uncertainty surrounding COVID-19, particularly at the start of the pandemic, and lack of information regarding the link between COVID-19 and CeD, patients typically have high levels of COVID-19 risk perceptions. Therefore, efforts should be made towards improving communication with patients with CeD and educating them based on emerging scientific evidence.

We recently demonstrated that the odds of contracting coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in patients with celiac disease (CeD) is similar to that of the general population. However, how patients with CeD perceive their COVID-19 risk may differ from their actual risk.

Risk perceptions are important in the context of a pandemic because a group’s perception of their susceptibility to infection influences their willingness to cooperate with preventative safety measures such as travel restrictions, hand washing, social distancing, and personal protective equipment use. However, overestimation of risk can contribute to negative mental and physical health consequences

The aim of this study was to investigate risk perceptions of contracting COVID-19 in patients with CeD and determine the factors that may influence their perception.

We distributed an international survey throughout 10 countries and collected data on demographics, diet, COVID-19 testing, and risk perceptions of COVID-19 in patients with CeD. Risk perception was assessed by asking individuals whether they believe patients with CeD are at an increased risk of contracting COVID-19 when compared to the general population. Logistic regression was used to determine the influencing factors associated with COVID-19 risk perception.

A total of 10737 participants with CeD completed the survey. The majority of patients with CeD perceived they were at a higher risk or were unsure if they were at a higher risk of contracting COVID-19 compared to the non-CeD population. A greater proportion of patients with CeD perceived an increased risk of contracting COVID-19 when compared to infections in general due to their CeD. Consequently, 34.8% reported taking extra COVID-19 precautions as a result of their CeD. Members of celiac associations were less likely to perceive an increased risk of COVID-19 when compared to non-members. Older age, male sex, and strict adherence to a GFD were associated with a lower perception of COVID-19 risk and the presence of comorbidities was associated with a higher perception of COVID-19 risk.

Overall, high levels of risk perceptions, such as those found in patients with CeD, may increase an individual’s pandemic-related stress and contribute to negative mental health consequences. Therefore, it is encouraged that public health officials maintain consistent communication with the public and healthcare providers with the celiac community.

Future studies specifically evaluating mental health in CeD could help determine the consequences of increased risk perceptions in this population.

We would like to thank all the individuals and associations who kindly participated in this study. We would also like to acknowledge the following individuals and associations for their major contributions to the recruitment of participants: Canadian Celiac Association - Melissa Secord (CEO) and Professional Advisory Committee (PAC); Beyond Celiac - Alice Bast and Kate Avery; Celiac Disease Foundation - Marilyn Geller; Coeliac Australia; Coeliac New Zealand; Aglutenados.- Carolina Rocha; Federación de Asociaciones de celiacos de España (FACE); Asociación de enfermos celiacos y sensibles al gluten de la Comunidad de Madrid; Asociación de celiacos de Cataluña; Asociación Celíaca Argentina (ACA); Asistencia al Celíaco de Argentina (ACELA); Grupo Promotor de la Ley Celíaca (GPLC); Canadian Association of Gastroenterology (CAG), Dr Juan Pinto Bruchmann (Sociedad de Gastroenterologia de Santiago del Estero); Mayur Tailor, M.Guadalupe, M.del Pilar, Magdalena Pinto-Sanchez, and Nonstopbsas - Roxana Baroni; De celiaco a celiaco - N. Groisman and G. Arce, for their contributions with social media distribution; president of ACELA, Santiago del Estero, Mrs. Reina Palavecino, Sociedad Argentina de Gastroenterologia (SAGE), Federacion Argentina de Gastroenterologia (FAGE), and Mrs. Julia Molina, director of Market Dixit Graphic Design and Digital marketing for their in kind support with promotion materials.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Canadian Association of Gastroenterology; American Gastroenterological Association; Society for the study of Celiac Disease; and Canadian Nutrition Society.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Canada

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Li J, Shu X S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Paules CI, Marston HD, Fauci AS. Coronavirus Infections-More Than Just the Common Cold. JAMA. 2020;323:707-708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1204] [Cited by in RCA: 1135] [Article Influence: 227.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cascella M, Rajnik M, Cuomo A, Dulebohn SC, Di Napoli R. Features, Evaluation, and Treatment of Coronavirus (COVID-19). January 16, 2021. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan–. [PubMed] |

| 3. | WHO. World Health Organization COVID-19 Explorer Geneva 2020. [Cited October 20, 2020]. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/. |

| 4. | Mårild K, Fredlund H, Ludvigsson JF. Increased risk of hospital admission for influenza in patients with celiac disease: a nationwide cohort study in Sweden. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2465-2473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Simons M, Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Risech-Neyman Y, Moss SF, Ludvigsson JF, Green PHR. Celiac Disease and Increased Risk of Pneumococcal Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Med. 2018;131:83-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ludvigsson JF, Wahlstrom J, Grunewald J, Ekbom A, Montgomery SM. Coeliac disease and risk of tuberculosis: a population based cohort study. Thorax. 2007;62:23-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zhen J, Stefanolo JP, Temprano MP, Tedesco S, Seiler C, Caminero AF, de-Madaria E, Huguet MM, Vivas S, Niveloni SI, Bercik P, Smecuol E, Uscanga L, Trucco E, Lopez V, Olano C, Mansueto P, Carroccio A, Green PHR, Day A, Tye-Din J, Bai JC, Ciacci C, Verdu EF, Lebwohl B, Pinto-Sanchez MI. The Risk of Contracting COVID-19 Is Not Increased in Patients With Celiac Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:391-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ferrer R, Klein WM. Risk perceptions and health behavior. Curr Opin Psychol. 2015;5:85-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 524] [Cited by in RCA: 526] [Article Influence: 52.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Adefuye AS, Abiona TC, Balogun JA, Lukobo-Durrell M. HIV sexual risk behaviors and perception of risk among college students: implications for planning interventions. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Brewer NT, Chapman GB, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, McCaul KD, Weinstein ND. Meta-analysis of the relationship between risk perception and health behavior: the example of vaccination. Health Psychol. 2007;26:136-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1097] [Cited by in RCA: 1116] [Article Influence: 62.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Dryhurst S, Schneider CR, Kerr J, Freeman ALJ, Recchia G, van der Bles AM, Spiegelhalter D, van der Linden S. Risk perceptions of COVID-19 around the world. J Risk Resear. 2020: 1-13. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 885] [Cited by in RCA: 775] [Article Influence: 155.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hiremath P, Suhas Kowshik CS, Manjunath M, Shettar M. COVID 19: Impact of lock-down on mental health and tips to overcome. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:102088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rajkumar RP. COVID-19 and mental health: A review of the existing literature. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;52:102066. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1943] [Cited by in RCA: 1826] [Article Influence: 365.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Clappison E, Hadjivassiliou M, Zis P. Psychiatric Manifestations of Coeliac Disease, a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2020;12:142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Siniscalchi M, Zingone F, Savarino EV, D'Odorico A, Ciacci C. COVID-19 pandemic perception in adults with celiac disease: an impulse to implement the use of telemedicine. Dig Liver Dis. 2020;52:1071-1075. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Silvester JA, Comino I, Kelly CP, Sousa C, Duerksen DR; DOGGIE BAG Study Group. Most Patients With Celiac Disease on Gluten-Free Diets Consume Measurable Amounts of Gluten. Gastroenterology 2020; 158: 1497-1499. e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38562] [Cited by in RCA: 36883] [Article Influence: 2305.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ludvigsson JF, Card T, Ciclitira PJ, Swift GL, Nasr I, Sanders DS, Ciacci C. Support for patients with celiac disease: A literature review. United European Gastroenterol J. 2015;3:146-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Jinga M, Popp A, Balaban DV, Dima A, Jurcut C. Physicians' attitude and perception regarding celiac disease: A questionnaire-based study. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2018;29:419-426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zipser RD, Farid M, Baisch D, Patel B, Patel D. Physician awareness of celiac disease: a need for further education. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:644-646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Li JB, Yang A, Dou K, Wang LX, Zhang MC, Lin XQ. Chinese public's knowledge, perceived severity, and perceived controllability of COVID-19 and their associations with emotional and behavioural reactions, social participation, and precautionary behaviour: a national survey. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 27.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Cori L, Bianchi F, Cadum E, Anthonj C. Risk Perception and COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 34.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Taylor L. Uruguay is winning against covid-19. This is how. BMJ. 2020;370:m3575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | de la Vega R, Ruíz-Barquín R, Boros S, Szabo A. Could attitudes toward COVID-19 in Spain render men more vulnerable than women? Glob Public Health. 2020;15:1278-1291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Rimal RN, Juon HS. Use of the Risk Perception Attitude Framework for Promoting Breast Cancer Prevention. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2010;40:287-310. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ding Y, Du X, Li Q, Zhang M, Zhang Q, Tan X, Liu Q. Risk perception of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and its related factors among college students in China during quarantine. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0237626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Canova C, Pitter G, Ludvigsson JF, Romor P, Zanier L, Zanotti R, Simonato L. Coeliac disease and asthma association in children: the role of antibiotic consumption. Eur Respir J. 2015;46:115-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Caio G, Volta U, Sapone A, Leffler DA, De Giorgio R, Catassi C, Fasano A. Celiac disease: a comprehensive current review. BMC Med. 2019;17:142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 564] [Cited by in RCA: 565] [Article Influence: 94.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sanyaolu A, Okorie C, Marinkovic A, Patidar R, Younis K, Desai P, Hosein Z, Padda I, Mangat J, Altaf M. Comorbidity and its Impact on Patients with COVID-19. SN Compr Clin Med. 2020: 1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 973] [Cited by in RCA: 781] [Article Influence: 156.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Thng ZX, De Smet MD, Lee CS, Gupta V, Smith JR, McCluskey PJ, Thorne JE, Kempen JH, Zierhut M, Nguyen QD, Pavesio C, Agrawal R. COVID-19 and immunosuppression: a review of current clinical experiences and implications for ophthalmology patients taking immunosuppressive drugs. Br J Ophthalmol. 2021;105:306-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Persoskie A, Ferrer RA, Klein WM. Association of cancer worry and perceived risk with doctor avoidance: an analysis of information avoidance in a nationally representative US sample. J Behav Med. 2014;37:977-987. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Nourazari S, Davis SR, Granovsky R, Austin R, Straff DJ, Joseph JW, Sanchez LD. Decreased hospital admissions through emergency departments during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Valitutti F, Zenzeri L, Mauro A, Pacifico R, Borrelli M, Muzzica S, Boccia G, Tipo V, Vajro P. Effect of Population Lockdown on Pediatric Emergency Room Demands in the Era of COVID-19. Front Pediatr. 2020;8:521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Saleem T, Sheikh N, Abbasi MH, Javed I, Khawar MB. COVID-19 containment and its unrestrained impact on epilepsy management in resource-limited areas of Pakistan. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;112:107476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Carlsson C, Baigi A, Killander D, Larsson US. Motives for becoming and remaining member of patient associations: a study of 1,810 Swedish individuals with cancer associations. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13:1035-1043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Carlsson C, Bendahl PO, Nilsson K, Nilbert M. Benefits from membership in cancer patient associations: relations to gender and involvement. Acta Oncol. 2006;45:559-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |