Published online Mar 7, 2020. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i9.984

Peer-review started: October 16, 2019

First decision: November 22, 2019

Revised: December 4, 2019

Accepted: February 21, 2020

Article in press: February 21, 2020

Published online: March 7, 2020

Processing time: 141 Days and 11.3 Hours

Although deficient procedures performed by impaired physicians have been reported for many specialists, such as surgeons and anesthesiologists, systematic literature review failed to reveal any reported cases of deficient endoscopies performed by gastroenterologists due to toxic encephalopathy. Yet gastroenterologists, like any individual, can rarely suffer acute-changes-in-mental-status from medical disorders, and these disorders may first manifest while performing gastrointestinal endoscopy because endoscopy comprises so much of their workday.

Among 181767 endoscopies performed by gastroenterologists at William-Beaumont-Hospital at Royal-Oak, two endoscopies were performed by normally highly qualified endoscopists who manifested bizarre endoscopic interpretation and technique during these endoscopies due to toxic encephalopathy. Case-1-endoscopist repeatedly insisted that gastric polyps were colonic polyps, and absurdly “pressed” endoscopic steering dials to “take” endoscopic photographs; Case-2-endoscopist repeatedly insisted that had intubated duodenum when intubating antrum, and wildly turned steering dials and bumped endoscopic tip forcefully against antral wall. Endoscopy nurses recognized endoscopists as impaired and informed endoscopy-unit-nurse-manager. She called Chief-of-Gastroenterology who advised endoscopists to terminate their esophagogastroduodenoscopies (fulfilling ethical imperative of “physician, first-do-no-harm”), and go to emergency room for medical evaluation. Both endoscopists complied. In-hospital-work-up revealed toxic encephalopathy in both from: case-1-urosepsis and left-ureteral-impacted-nephrolithiasis; and case-2-dehydration and accidental ingestion of suspected illicit drug given by unidentified stranger. Endoscopists rapidly recovered with medical therapy.

This rare syndrome (0.0011% of endoscopies) may manifest abruptly as bizarre endoscopic interpretation and technique due to impairment of endoscopists by toxic encephalopathy. Recommended management (followed in both cases): 1-recognize incident as medical emergency demanding immediate action to prevent iatrogenic patient injury; 2- inform Chief-of-Gastroenterology; and 3-immediately intervene to abort endoscopy to protect patient. Syndromic features require further study.

Core tip: Two novel cases are reported of impaired endoscopists manifesting bizarre-endoscopic-interpretation-and-technique due to toxic encephalopathy among 181767 endoscopies performed at William-Beaumont-Hospital-Royal-Oak. Case-1-endoscopist repeatedly insisted that gastric polyps were colonic polyps, and absurdly “pressed” endoscopic steering dials to photograph gastric lesions. Case-2-endoscopist repeatedly insisted that had intubated duodenum when intubating antrum, and erratically turned steering dials and bumped endoscopic tip against antral wall. Endoscopists were advised to terminate their esophagogastroduodenoscopies, fulfilling ethical imperative: “physician-first-do-no-harm”. In-hospital-work-up revealed toxic encephalopathies from urosepsis, or inadvertently ingesting “illicit drug”. Both endoscopists rapidly recovered with medical therapy. These potential-medical-emergencies require aborting endoscopy to prevent iatrogenic patient injury.

- Citation: Cappell MS. Two case reports of novel syndrome of bizarre performance of gastrointestinal endoscopy due to toxic encephalopathy of endoscopists among 181767 endoscopies in a 13-year-university hospital review: Endoscopists, first do no harm! World J Gastroenterol 2020; 26(9): 984-991

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v26/i9/984.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v26.i9.984

Gastroenterologists (GIs), like any individual, can suffer acute-changes-in-mental-status from medical disorders, and these medical disorders may rarely first manifest while performing gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy because endoscopy comprises so much of their workday. Review of 181767 GI endoscopies performed by GIs at a large university teaching hospital revealed 2 cases (0.0011%) of acute-change-in-mental-status by GIs first manifesting during endoscopy, as reported herein. This novel work reports syndromic features, including nature of bizarre endoscopic performance, health professionals who reported incidents, and medical causes of transient impairment; recommends chain-of-command to manage medical crises; and emphasizes the need to immediately abort endoscopy to prevent iatrogenic patient injury (fulfilling ethical imperative of Hippocratic Oath, “Physician, first do no harm!”)[1].

Dr. Cappell prospectively intervened administratively during both incidents, and was involved soon thereafter in investigating the incidents for quality assurance as Chief-of-Gastroenterology (GI), November 2006-September 2019, at William Beaumont Hospital, Royal Oak, a large university hospital of Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine. Computerized search of all outpatient and inpatient esophagogastroduodenoscopies (EGDs), sigmoidoscopies, and colonoscopies performed in hospital endoscopy unit by GIs using Provations (800 Washington Avenue North, Minneapolis, MN 555401), a computerized endoscopy reporting system (using terms “abort”, “aborted”, “incomplete”, “stop”, “stopped”, “terminate”, “terminated”, “impaired”, or “unsatisfactory” [endoscopy /endoscopist]), did not reveal any more aborted endoscopies because of impaired endoscopists. Study excluded surgeons performing GI endoscopy because Chief-of-GI lacked prospective knowledge of such incidents due to a separate quality assurance pathway. This study was exempted/approved by the William Beaumont Hospital Institutional Review Board on 9/4/19. Dr. Cappell claims expertise in quality assurance based on professional experience as senior GI administrator (1995-2019) at the five following teaching hospitals (with medical residencies and GI fellowships): Maimonides Hospital, Brooklyn, NY; Woodhull Hospital, Brooklyn, NY; Saint Barnabas Hospital, Bronx, NY; Albert Einstein Hospital, Philadelphia, PA; and William Beaumont Hospital, Royal Oak, MI.

Literature related to impaired endoscopists at endoscopy was systematically searched using Pubmed and Ovid with the following terms [“incapacitated” or “impaired” or “incompetent”] AND [“gastroenterologist” or “endoscopist” or “surgeon” or “physician” or “doctor”]. Abstracts of all identified publications were reviewed. This search failed to reveal prior publications on impaired endoscopists, although several papers were identified about impaired physicians, surgeons, anesthesiologists, or other specialists due to alcoholism or drug dependency.

For clarification, the subjects of these two case reports are not the patients undergoing the endoscopies, but the gastroenterologists performing the endoscopies.

Chief-of-GI was paged stat by the endoscopy-unit-nurse-administrator about an elderly, highly experienced, and normally, highly competent endoscopist who suffered an acute-change-in-mental-status while performing EGD manifested by bizarre behavior, including repeatedly insisting that gastric polyps were in colon, and attempting to endoscopically photograph these polyps by absurdly pressing the steering dials instead of the photography button. Endoscopy nurse recognized this behavior as bizarre and immediately notified endoscopy-unit-nurse-administrator. The summoned Chief-of-GI noted the endoscopist was confused, dizzy, and unsteady; and advised this endoscopist to immediately abort the EGD, cancel upcoming endoscopies, and go to emergency room (ER) for medical evaluation. The endoscopist complied. The Chief-of-GI accompanied the impaired endoscopist to ER.

The impaired endoscopist was experiencing progressive left lower quadrant abdominal pain, hardly eating or drinking fluids, and experiencing orthostatic dizziness during the past 24 h. He had chronic, benign, prostatic hypertrophy. He had no history of neuropsychiatric-disorders/illicit-drug-use/alcoholism/prior similar episodes. Family history was noncontributory. He was bending over in pain and clutching his left lower abdominal quadrant while walking several steps to a waiting wheelchair. Physical examination on admission revealed blood pressure of 181/85 mmHg, pulse of 84 beats/min with orthostasis, respiratory rate of 18 breaths/min, and temperature of 37.9 °C. Mucous membranes were dry, skin turgor was deceased, and axillary sweat was absent. The abdomen was soft, nontender, non-distended, and without hepatosplenomegaly. The left flank was moderately tender. Digital rectal examination revealed guaiac negative stool, and diffuse severe prostatomegaly, without induration. He was moderately confused; oriented to place, person, and year but not month and day. He was conversant and cognizant of his confusion. Formal neurologic examination by a neurologist revealed no other neurologic abnormalities.

There were 16800 leukocytes/mm3 (normal: 3500-10100 leukocytes/mm3), and 13700 neutrophils/mm3 (normal: 1600-7200 neutrophils/mm3). Hemoglobin was within normal limits. Levels of routine serum electrolytes, serum glucose, basic metabolic panel, lactic acid, and routine thyroid function tests were within normal limits. An electrocardiogram (EKG) and serial troponin levels showed no cardiac ischemia or cardiac arrhythmia. Blood alcohol level and urine screen for 8 commonly abused drugs were negative.

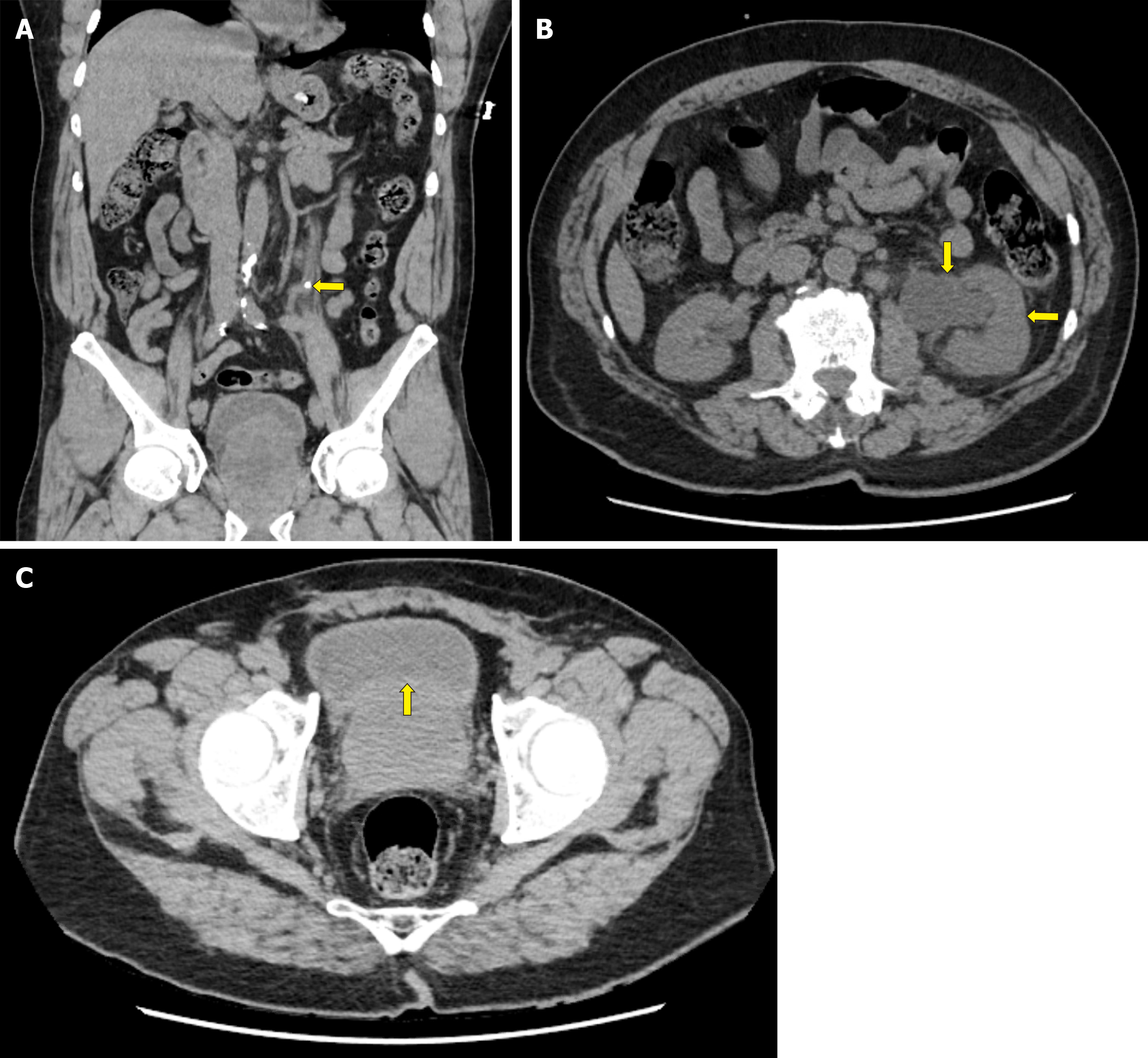

Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) level was 19 mg/dL (normal: 8-22 mg/dL), and creatinine was 2.01 mg/dL (normal: 0.60-1.40 mg/dL). Abdomino-pelvic CT revealed moderate, left-sided, hydroureteronephrosis, mild left perinephric stranding, a 5.5-mm-wide-radioopaque-stone obstructing the left mid-ureter (Figure 1A and B), and an extremely large prostate gland protruding into the bladder (Figure 1C). Urinalysis revealed ketonuria (likely from early starvation ketosis), and microscopic hematuria (from kidney stone). Head computerized tomography (CT) and brain magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) showed unremarkable cerebral anatomy and cerebral vessels, respectively.

The Chief-of-GI was paged stat by the endoscopy-unit-nurse-administrator about a middle-aged, highly experienced, and normally highly competent endoscopist who suffered an acute-change-in-mental-status while performing EGD manifested by bizarre behavior, including insisting that he was intubated in duodenum when he had actually intubated gastric antrum, and wildly turning the steering dials and bumping forcefully against antral wall while trying to intubate the pylorus. The prior evening, he had taken diazepam 5 mg orally, and drank 24 ounces of beer to relieve lower back pain after twisting his lower back while carrying a heavy pile of medical charts (incident preceded advent of electronic medical records). The endoscopist had not eaten any food or drank any fluids for 16 h before EGD because of residual back pain. After performing one EGD in the morning without incident, he took two purported “motrin” pills of unknown dosage donated by an unidentified stranger (this event was witnessed). He soon became dizzy and disoriented. The endoscopy nurse noted the endoscopist’s bizarre behavior during the next EGD and immediately notified the endoscopy-unit-nurse-administrator who paged the Chief-of-GI stat. After noting that the endoscopist was confused, dizzy, lethargic, unsteady, and oriented to place and person but not time, the summoned Chief-of-GI advised the endoscopist to abort the EGD, cancel upcoming endoscopies, and go to ER for medical evaluation. The endoscopist complied. The Chief-of-GI accompanied the impaired endoscopist to ER.

Past medical history revealed chronic back pain for which he intermittently took motrin 200 mg orally, three times daily; and mild anxiety occasionally requiring diazepam, 5 mg orally, as needed. The endoscopist had no history of neuropsychiatric-disorders/illicit-drug-use/alcoholism/prior similar episodes. Family history was noncontributory. Upon evaluation in ER 30 min later, the endoscopist was asymptomatic and appeared completely recovered from his change-in-mental-status. His blood pressure was 130/91 mmHg, pulse was 82 beats/min and regular, respiratory rate was 18 breaths/min, and temperature was 36.2 °C. He had dry mucous membranes, absent axillary sweat, and poor skin turgor. His abdomen was soft and nontender. He was alert; oriented to time, place, and person; and not anymore confused. Formal neurologic examination by a neurologist revealed no neurologic abnormalities. Routine serum electrolytes, basic metabolic panel, BUN, creatinine, complete hemogram, and urinalysis were within normal limits. Blood alcohol level and urine screen for 8 commonly abused drugs were negative. EKG and serial troponin levels showed no cardiac ischemia or cardiac arrhythmias. Head CT and brain MRA with IV contrast revealed no abnormalities.

Endoscopist was confused and disoriented at EGD due to toxic encephalopathy secondary to kidney stone obstructing left ureter, complicated by left-sided hydroureteronephrosis, urosepsis, and dehydration.

Transient confusion during EGD attributed to brief toxic encephalopathy attributed to potential neuropsychiatric effects of alleged “motrin” pills given by a stranger, exacerbated by dehydration and acute back pain.

Endoscopist received profuse IV hydration, and IV ceftriaxone 1 g/d for presumed urosepsis. Cystourethroscopy revealed left, mid-ureteral obstruction from an impacted kidney stone. A J-stent was inserted into left ureter to bypass the ureteral obstruction, and stone removal was deferred. Urine culture obtained from left ureter during cystourethroscopy revealed > 10000 colony-forming-units/mL (normal: < 10000 cfu/mL). He was discharged 1 d later when the creatinine level declined to 1.8 mg/dL, and received trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole orally for 5 d as an outpatient. At repeat cystourethroscopy 10 d later, the left ureteral stone was successfully extracted via basket.

Patient was admitted overnight for vigorous hydration and observation.

The patient’s creatinine and BUN levels rapidly normalized. Chemical analysis revealed a calcium oxalate monohydrate and dehydrate stone. The endoscopist resumed seeing patients and performing GI endoscopy 10 d later with no neurologic sequelae.

Patient became asymptomatic and was discharged the next morning. He resumed seeing patients and performing endoscopy 3 d after hospital discharge, with no neurologic sequelae.

Both cases exhibited five notable syndromic features. First, this syndrome is rare (0.0011% of GI endoscopies performed by GIs). This is not surprising because GIs performing endoscopy are generally healthy. Contrariwise, this syndrome can rarely occur because GIs, like other individuals, are subject to human frailties, and these frailties could manifest during endoscopy, which comprises a large part of their workday. Second, impairment first manifested abruptly as bizarre endoscopic interpretation and technique at endoscopy. Changes-in-mental-status may only be first appreciated during endoscopy because endoscopy requires sophisticated cognitive and technical skills which can be readily affected by a change-in-mental-status. Third, in both cases endoscopy nurses first detected this impairment. Endoscopy nurses are highly trained, highly focused on endoscopy, and can directly view endoscopic findings by video-monitor, to detect aberrant cognitive and technical behavior by endoscopists. Both nurses recognizing bizarre behavior were very experienced (> 8 years nursing experience). Fourth, in both cases the change-in-mental-status was caused by metabolic encephalopathy: Case-1-from urosepsis from left ureteral obstruction from kidney stone impacted in left ureter (prostatomegaly a possible predisposing factor), which was compounded by dehydration and ketonuria; and case-2-occurring soon after taking two putative “motrin” pills given by a stranger and resolving soon thereafter, suggesting that the putative “motrin” pills were the proximate cause of impairment, probably exacerbated by dehydration. The impaired endoscopist in case-2 speculated that the pill was not “motrin” but a neuropsychiatric drug which could have been administered mistakenly or deliberately (as in “slipping a Mickey Finn” alluding to Mickey Finn, a bartender who would spike alcoholic drinks with chloral hydrate to make clients sleepy to rob them later)[2]. Change-in-mental-status was not likely an allergic reaction to motrin because the endoscopist had previously taken motrin frequently without toxicity. Fifth, both impaired endoscopists rapidly recovered from their toxic encephalopathies, and resumed seeing patients and performing endoscopy within 10 d after hospitalization.

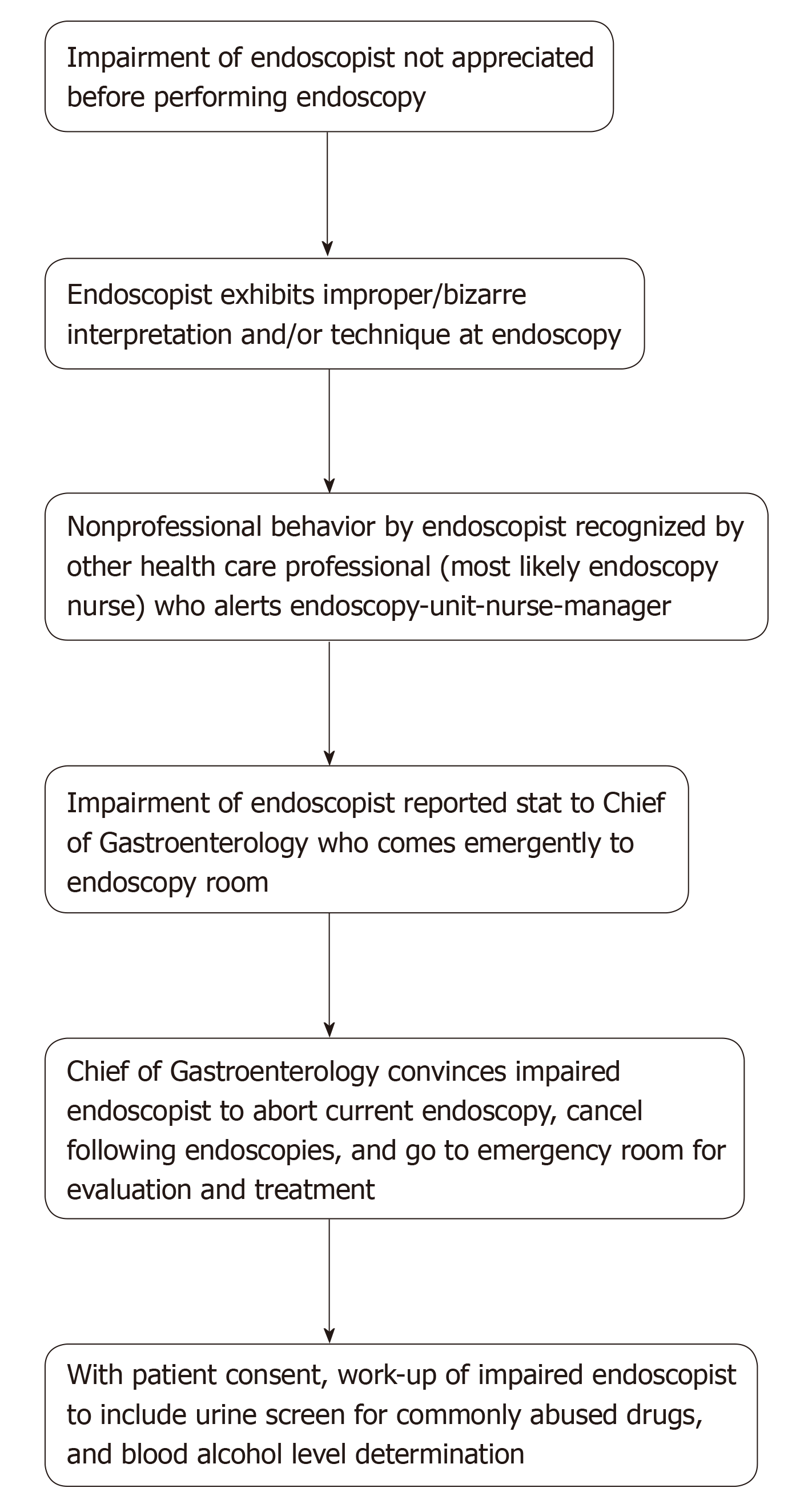

The following five administrative actions are recommended to manage the crises (Figure 2). First, hospital administrators should recognize such incidents as medical emergencies because of potential iatrogenic patient injury (e.g. GI perforation) by impaired endoscopists. For example, the second impaired endoscopist wildly turned the steering dials, and forcefully bumped the endoscopic tip against the antral wall. These effects of metabolic encephalopathy are biologically reasonable. Like a drunken driver crashing a car due to erratic driving, an impaired endoscopist may bump the endoscopic tip forcefully against the GI wall due to erratic steering and potentially cause GI perforation. Inebriated drivers often fail the field sobriety test because they cannot walk in a straight line. The neurologist, Oliver Sacks, published numerous case reports of bizarre behavior due to neurologic impairments, such as a patient who mistook his wife for a hat due to visual agnosia[3]. Second, this work illustrates a reasonable chain-of-command for crisis management: Endoscopy nurse to endoscopy-unit-nurse-administrator to Chief-of-GI. This avoids endoscopy nurses awkwardly confronting endoscopists about faulty endoscopic technique, and defers action until after evaluation by Chief-of-GI, who as a practitioner and peer of impaired endoscopists, should be highly familiar with endoscopic standards of care. Third, the Chief-of-GI was paged stat, and responded immediately, as required for an emergency. Fourth, the Chief-of-GI strongly advised impaired endoscopists in both cases to abort the EGDs, and cancel all upcoming endoscopies to prevent iatrogenic injury (following ethical imperative of “Physician, first do no harm!”)[1]; this was accomplished by persuasion. Fifth, impaired endoscopists should be advised to go to ER as recommended for diagnosis and treatment of acute-changes-in-mental-status.

The following two optional recommendations are proposed. First, if the patient agrees, the Chief-of-GI may accompany an impaired endoscopist to demonstrate professional camaraderie and facilitate ER evaluation. Second, with patient consent, a urine screen for commonly abused drugs and a blood alcohol level should be determined, because these agents account for approximately 30% of cases of acute-change-in-mental-status[4]. Moreover, detection of drug addiction by physicians is imperative to prevent patient harm[1,5].

Systematic literature review revealed that the reported cases are novel, even though some literature exists on impaired physicians, surgeons, anesthesiologists, and other specialists, especially from alcoholism or drug dependency[6-10].

Toxic encephalopathy can affect the cognitive behavior of any physician in any specialty or subspecialty performing medical, surgical, or other specialty consults; can affect the technical performance of procedures or surgery by physicians in any medical, surgical, or other specialty, such as cardiac catheterization, interventional angiography, or intestinal surgery, as illustrated for GI endoscopy. Moreover, toxic encephalopathy can affect other activities, such as driving a car or operating heavy machinery, due to cognitive impairment. Individuals suffering from toxic encephalopathy should refrain from these activities, and their supervisors should intervene appropriately if necessary.

This study has limitations. First, it is retrospective. However, the author, as Chief-of-GI, prospectively investigated and managed the work-up of the impaired endoscopists in real time, and thoroughly analyzed the events shortly thereafter for quality assurance. Second, the author cannot exclude missed cases of this syndrome during the study period, but such cases seem unlikely because this syndrome is so conspicuous. Third, recommendations on incident management are based on expert opinion by one GI, which may be subject to individual bias. However, Dr. Cappell has extensive experience in senior administrative positions in academic gastroenterology (see Methods), has published very extensively on GI endoscopy[11-13], and has published on GI quality assurance[14,15]. Fourth, this syndrome cannot be reliably characterized by just two cases, and the findings require corroboration, even though all reported syndromic features are biologically reasonable.

Two novel cases are reported of acute-change-in-mental-status manifesting as bizarre endoscopic interpretation and technique from toxic encephalopathy. Such incidents should be handled emergently to disengage impaired endoscopists from their patients undergoing endoscopy because of dangers of impaired endoscopists causing iatrogenic injury (e.g., GI perforation).

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: American Gastroenterology Association; American College of Gastroenterology.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Dutta A, Efthymiou A, Dinç T S-Editor: Wang YQ L-Editor: A E-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Glasscheibe HS. New York: Putnam 1964; 164 The march of medicine: The emergence and triumph of modern medicine, 1964: 164. |

| 2. | Wikipedia. Mickey Finn (drugs). Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mickey_Finn_(drugs). |

| 3. | Sacks O. The man who mistook his wife for a hat and other clinical tales. New York: Summit Books, 1985: 8-22. |

| 5. | Watkins D. Substance abuse and the impaired provider. J Healthc Risk Manag. 2010;30:26-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | The impaired surgeon. Diagnosis, treatment, and reentry. Committee on the Impaired Physician, American College of Surgeons Board of Governors. Bull Am Coll Surg. 1992;77:29-32, 39. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Jones JW, McCullough LB, Richman BW. An impaired surgeon, a conflict of interest, and supervisory responsibilities. Surgery. 2004;135:449-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jones JW, McCullough LB. The question of an impaired surgeon dilemma. J Vasc Surg. 2012;56:1761-1762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Killewich LA. The impaired surgeon: revisiting Halstead. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50:440-441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sudan R, Seymour K. The Impaired Surgeon. Surg Clin North Am. 2016;96:89-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cappell MS. Evaluating the Safety of Endoscopy During Pregnancy: The Robust Statistical Power vs Limitations of a National Registry Study. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:475-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cappell MS, Iacovone FM Jr. Safety and efficacy of esophagogastroduodenoscopy after myocardial infarction. Am J Med. 1999;106:29-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cappell MS. Safety and efficacy of colonoscopy after myocardial infarction: an analysis of 100 study patients and 100 control patients at two tertiary cardiac referral hospitals. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:901-909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Cappell MS. Complaints against gastroenterology fellows. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:153-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cappell MS, Friedel DM. Stricter national standards are required for credentialing of endoscopic-retrograde-cholangiopancreatography in the United States. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:3468-3483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |