Published online Nov 28, 2020. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i44.7036

Peer-review started: August 20, 2020

First decision: September 12, 2020

Revised: September 24, 2020

Accepted: October 13, 2020

Article in press: October 13, 2020

Published online: November 28, 2020

Processing time: 98 Days and 23.8 Hours

Endoscopic papillectomy (EP) is rapidly replacing traditional surgical resection and is a less invasive procedure for the treatment of duodenal papillary tumors in selected patients. With the expansion of indications, concerns regarding EP include not only technical difficulties, but also the risk of complications, especially delayed duodenal perforation. Delayed perforation after EP is a rare but fatal complication. Exposure of the artificial ulcer to bile and pancreatic juice is considered to be one of the causes of delayed perforation after EP. Draining bile and pancreatic juice away from the wound may help to prevent delayed perforation.

To evaluate the feasibility and safety of placing overlength biliary and pancreatic stents after EP.

This is a single-center, retrospective study. Five patients with exposure or injury of the muscularis propria after EP were included. A 7-Fr overlength biliary stent and a 7-Fr overlength pancreatic stent, modified by an endoscopic nasobiliary drainage tube, were placed in the common bile duct and pancreatic duct, respectively, and the bile and pancreatic juice were drained to the proximal jejunum.

EP and overlength stents placement were technically feasible in all five patients (63 ± 12 years), with an average operative time of 63.0 ± 5.6 min. Of the five lesions (median size 20 mm, range 15-35 mm), four achieved en bloc excision and curative resection. The final histopathological diagnoses of the endoscopic specimen were one tubular adenoma with high-grade dysplasia (HGD), one tubulovillous adenoma with low-grade dysplasia, one hamartomatous polyp with HGD, one poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma and one atypical juvenile polyposis with tubulovillous adenoma, HGD and field cancerization invading the muscularis mucosae and submucosa. There were no stent-related complications, but one papillectomy-related complication (mild acute pancreatitis) occurred without any episodes of bleeding, perforation, cholangitis or late-onset duct stenosis.

For patients with exposure or injury of the muscularis propria after EP, the placement of overlength biliary and pancreatic stents is a feasible and useful technique to prevent delayed perforation.

Core Tip: This is a retrospective study to evaluate the feasibility and safety of overlength biliary and pancreatic stents placement after endoscopic papillectomy (EP). Five patients with exposure or injury of the muscularis propria after EP were included. Overlength biliary and pancreatic stents, modified by an endoscopic nasobiliary drainage tube, were placed, respectively, and the bile and pancreatic juice were drained to the proximal jejunum. EP and stents placement were technically feasible in all patients. One papillectomy-related complication (mild acute pancreatitis) occurred without any episodes of bleeding, perforation or cholangitis. Overlength biliary and pancreatic stents placement after EP is a feasible and useful technique to prevent delayed perforation.

- Citation: Wu L, Liu F, Zhang N, Wang XP, Li W. Endoscopic pancreaticobiliary drainage with overlength stents to prevent delayed perforation after endoscopic papillectomy: A pilot study. World J Gastroenterol 2020; 26(44): 7036-7045

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v26/i44/7036.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v26.i44.7036

Tumors arising in the major duodenal papilla can potentially undergo the adenoma-carcinoma sequence, making complete removal mandatory for curative therapy[1]. Endoscopic papillectomy (EP) is rapidly replacing classic surgical resection and is a less invasive procedure. However, the indications for endoscopic resection have not been fully established, and endoscopic procedures have not been standardized. The main criteria for EP include a lesion size less than 5 cm, absence of extension into the biliary or pancreatic duct, no invasion of the duodenal muscular layer and no evidence of malignancy in endoscopic findings, such as ulceration, spontaneous bleeding and friability[2,3]. However, with the application of techniques such as endoscopic piecemeal resection and balloon traction, as well as the popularization of the concept of “total biopsy”, more and more larger size, intraductal growth, suspected malignant and even early cancerous papillary lesions can be treated by EP[4-8].

With the expansion of indications, concerns regarding EP include not only technical difficulties, but also the risk of complications, especially delayed duodenal perforation. The duodenal wall is very thin, and the artificial ulcer after resection is exposed to bile and pancreatic juice, which are two important causes of delayed perforation[9,10]. Although the application of an endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) tube can achieve external drainage of bile, it is generally unable to drain pancreatic juice at the same time and may cause stress due to naso-pharyngeal discomfort; while the conventional plastic biliary and pancreatic stents cannot drain bile and pancreatic juice to a distance because of its limited length. These drainage methods cannot avoid the erosion of the artificial ulcer by bile and/or pancreatic juice after EP. Therefore, we modified the ENBD tubes into overlength biliary and pancreatic stents to drain bile and pancreatic juice to the proximal jejunum. The aim of the present study was to determine the feasibility and the safety of this method.

Between February 2019 and December 2019, a total of twenty patients with major duodenal papilla lesions were admitted to The Third Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, The First Medical Center of Chinese PLA General Hospital. Prior to EP, the platelet count, prothrombin time, and partial thromboplastin time were measured to confirm the absence of a tendency toward bleeding. A computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen was performed to determine whether there was local spread or distant metastasis, and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) and/or intraductal ultrasonography (IDUS) were performed to evaluate the anatomy of the pancreatic duct and intraductal extension of the tumor. Endoscopic biopsy was used to evaluate the histopathology of papillary lesions.

Indications for EP were as follows: Lesions of the duodenal major papilla (regardless of size and laterally spreading component) without muscularis propria invasion, with less than 1 cm (from the edge of the papillar to the end of the bile duct) intraductal growth and no evidence of invasive malignancy on endoscopic assessment (i.e., ulceration, spontaneous bleeding, hard consistency and friability)[2-8]. After EP, patients with exposure or injury of the muscularis propria were included for overlength biliary and pancreatic stents placement. Exposure or injury of the muscularis propria after EP was defined as obvious exposure or even damage of muscle fibrous tissue found in the wound on endoscopic assessment.

Of the twenty patients, five had advanced duodenal papillary carcinoma and were unsuitable for endoscopic resection, and ten cases (Supplementary Figure 1) had no obvious exposure or injury of the muscularis propria after EP (then designated for conventional plastic biliary and/or pancreatic stents placement), were excluded. Finally, only five patients (Supplementary Figure 2) with exposure or injury of the muscularis propria after EP were selected for overlength biliary and pancreatic stents placement. All patients gave informed consent to the procedure and were aware of the option of surgical treatment. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Chinese PLA General Hospital.

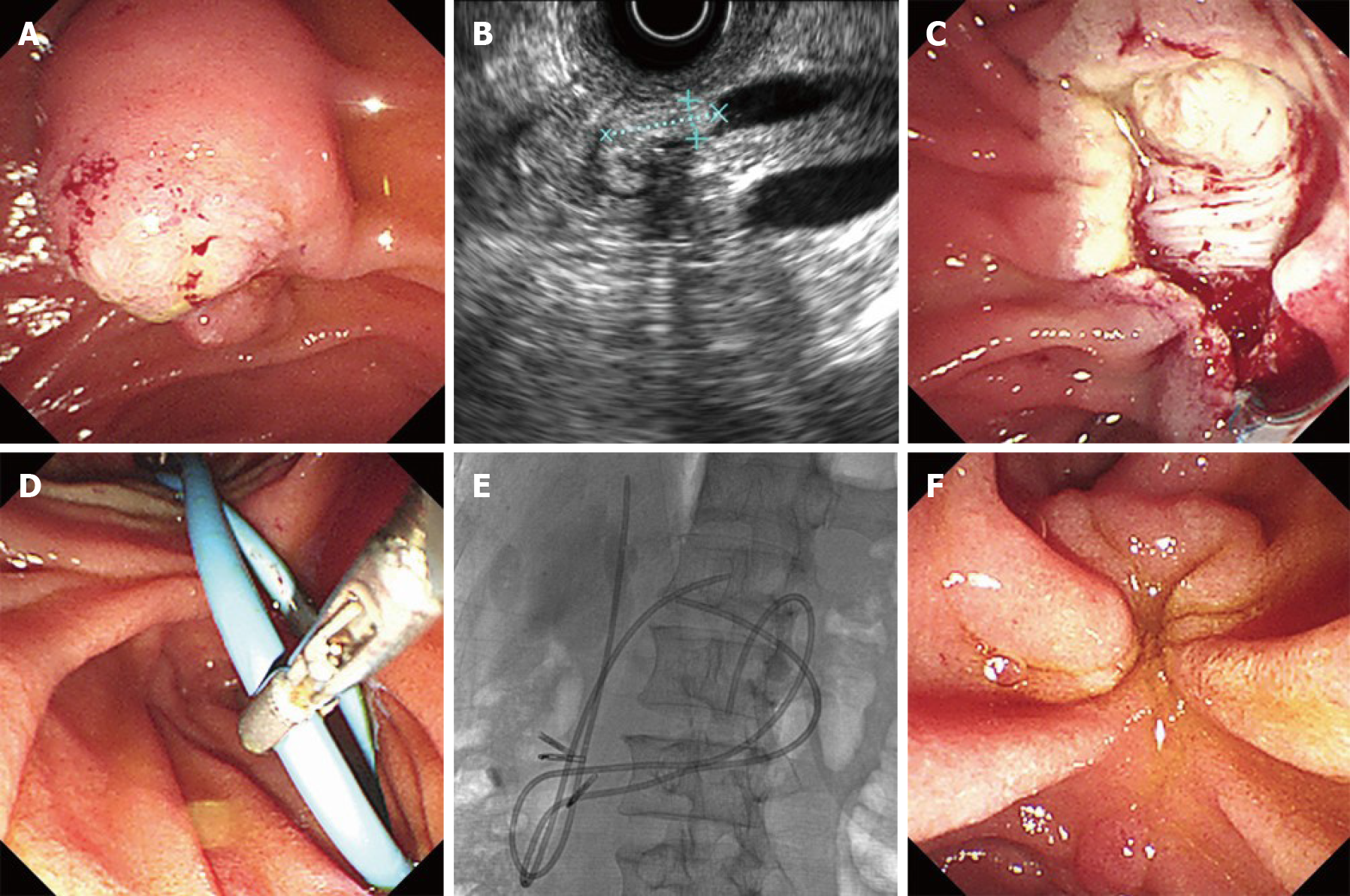

EP was performed by Dr. Li W, who has more than twenty years of experience in interventional endoscopy. The procedure was detailed in our previous report[3]. Briefly, the patients were placed in the prone position, intravenously sedated with midazolam and/or propofol, and monitored by pulse oximetry. Prophylactic antibiotics were given to all patients, and all papillectomies were performed with patients under intravenous anesthesia. The duodenoscope (TJF-240/TJF-260V; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was advanced to the descending portion of the duodenum, and the morphology of the duodenal papilla was carefully inspected. Before resection, submucosal injection was not generally performed, except in lesions involving the duodenal wall. A snare device (SD-7P-1/SD-221L-25; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was inserted via the endoscopic biopsy port, and then, the endoscopist adjusted the snare to grasp the lesion, which was then excised using standard electrocautery (Figure 1A and C). In order to achieve radical resection, we expanded the depth and breadth of resection in EP. Lesions that could not be resected en bloc were resected in a piecemeal fashion, and any suspicious residual tissue after resection was removed by argon plasma coagulation or a polypectomy multipolar probe. When a large mucosal defect (length ≥ 2 cm) was noted after EP, endoscopic closure was performed at the anal side of cutting using endoscopic hemoclips. A basket or grasper was used to extract the resected specimens. All resected specimens were immediately retrieved and submitted for histological analysis by serial sectioning.

After EP, in all five patients with exposure or injury of the muscularis propria, a 7-Fr overlength biliary stent and a 7-Fr overlength pancreatic stent, modified by ENBD tubes (ENBD-7-NAG-C; COOK, Ireland), were placed in the common bile duct and in the pancreatic duct. The overlength bile duct or pancreatic duct stent was divided into two parts: The duct segment and the intestinal segment, in which the length of the duct segment was the measured length of the common bile duct or the main pancreatic duct, while the intestinal segment length was extended by about 20 cm on the basis of the length of the duct segment to ensure that the distal end of the stent reached the jejunum (Figure 1D and E). The biliary and pancreatic stents were typically removed during the first follow-up visit at three months.

Complications were divided into early (acute pancreatitis, bleeding, and perforation) and late (post-EP stenosis) complications. Any bleeding during the procedure was immediately controlled with a local injection of 1:10000 epinephrine, hot-biopsy forceps (Coagrasper; Olympus) and/or hemoclips (Olympus), and was not considered a bleeding complication. Only clinically evident bleeding such as hematemesis or hematochezia with a progressive decrease in hemoglobin that occurred after completion of the procedure was regarded as a complication. Post-EP pancreatitis was defined as a threefold increase in pancreatic enzymes with abdominal pain[11]. Upper abdominal CT scan was routinely performed in all cases after EP. Delayed perforation was defined as the presence of a transmural defect by emergency gastroscopy or radiographic evidence of free retroperitoneal or intraperitoneal air by CT scan.

The definitions of complete resection, endoscopic success, and recurrence were described in our previous study[3]: Complete resection of ampullary adenomas was confirmed when no residual tissue was found at the 3-mo follow-up endoscopy and endoscopic forceps biopsy; endoscopic success was defined as complete resection of the lesion without residual tumor tissue and when no recurrence was evident at the 6-mo follow-up after EP; recurrence was defined as discovery of a lesion after the most recent negative surveillance endoscopy or endoscopic biopsy. The need for surgical resection after EP was regarded as endoscopic failure.

Follow-up endoscopy with biopsy was then performed after 3 and 6 mo. If the biopsy results showed no tumor remnants or the absence of possible recurrence, annual endoscopic follow-up examinations were recommended. Successful resection of the tumor, successful stent placement, operative time, early complications, late complications and tumor recurrence, were evaluated. Normally distributed continuous variables, non-normally distributed variables and dichotomous variables were presented as mean (± SD), median (range) or simple proportions, respectively.

The five patients included were men, with a mean age of 63 ± 12 years. Three of these patients were asymptomatic at diagnosis and two presented with abdominal pain. The median size of the tumors was 20 mm (range 15-35 mm). Pre-operative EUS and/or IDUS showed extension of the biliary duct in one case (Figure 1B), absence of any extension of the pancreatic duct in all cases, a tumor confined to the mucosal layer in three cases and a tumor invading the submucosa in two cases; none of these patients were found to be positive for intra-abdominal neoplastic nodes. Preoperative histology was available in all five cases, and showed adenomatoid hyperplasia in two cases, tubular adenoma with adenomatoid hyperplasia in one case, tubular adenoma in one case, and inflammation with high-grade dysplasia (HGD) and suspected field cancerization in one case (Table 1).

| No. | Sex | Age (yr) | Clinical presentation | Tumor size (mm) | Biopsy pathology |

| 1 | M | 58 | Abdominal pain | 20 | Adenomatoid hyperplasia/LGD |

| 2 | M | 73 | Incidental finding | 17 | Tubular adenoma |

| 3 | M | 50 | Incidental finding | 25 | Adenomatoid hyperplasia |

| 4 | M | 79 | Incidental finding | 35 | Inflammation/adenomatoid hyperplasia |

| 5 | M | 56 | Abdominal pain | 15 | Inflammation/HGD/field cancerization? |

An EP was technically feasible in all five patients. Submucosal injection was performed in one of the five cases. En bloc resection was achieved in four cases, piecemeal resection in one case, and exposure or injury of the muscularis propria was observed in all five cases. After EP, overlength biliary and pancreatic stents were placed. The length of overlength biliary stents varied from 35 cm to 38 cm, and the length of the duct segment was 13 cm to 14 cm. The total length of the pancreatic stents varied from 30 cm to 35 cm, and the duct segment was 11 cm to 12 cm. The average operative time was 63.0 ± 5.6 min (Table 2).

| No. | Tumor size (mm) | Submucosal injection | Resection | Length of biliary stent T/D (mm) | Length of pancreatic stents T/D (mm) | Operative time (min) | Complications | Additional therapy | Recurrence | Follow-up (mo) |

| 1 | 20 | (-) | En bloc | 35/13 | 35/12 | 61 | (-) | PPPD | (-) | 17 |

| 2 | 17 | (+) | En bloc | 35/13 | 35/12 | 55 | Panceatitis | (-) | (-) | 15 |

| 3 | 25 | (-) | Two Pieces | 35/14 | 35/12 | 63 | (-) | (-) | (-) | 12 |

| 4 | 35 | (-) | En bloc | 33/14 | 30/12 | 70 | (-) | (-) | (-) | 8 |

| 5 | 15 | (-) | En bloc | 38/13 | 35/11 | 66 | (-) | (-) | (-) | 8 |

One patient developed mild pancreatitis which resolved with conservative management. No bleeding, perforation, cholangitis or late-onset duct stenosis occurred. There was no procedure-related mortality.

Of the five lesions, four were completely resected with tumor-free lateral and basal margins. The final histopathological diagnoses of the endoscopic specimens were: One tubular adenoma, one tubulovillous adenoma, one hamartomatous polyp, one adenocarcinoma and one atypical juvenile polyposis with tubulovillous adenoma (Table 3). Compared with biopsy pathology, the final pathological diagnosis was underestimated in four of the five cases. Among the three cases of adenomas, two cases were associated with HGD, and one case with low-grade dysplasia (LGD) and the depth of invasion was confined to the mucosa. In the case of atypical juvenile polyposis with tubulovillous adenoma, HGD and field cancerization were found. The depth of cancerization invaded muscularis mucosae and submucosa, but the surgical margin was negative. The case of adenocarcinoma was pathologically proved to be poorly differentiated, and the depth of invasion reached the proper muscle layer of the intestinal wall, close to the incisal margin, which was significantly degenerated by electrocoagulation. After a multidisciplinary collaborative case discussion, the patient was referred for surgery and underwent pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy. The patients have been followed-up for a mean of 12 mo (range 8-17 mo), and no recurrences have been observed.

| No. | Tumor size (mm) | Biopsy pathology | Final pathology | Depth of invasion | Mucosal margin | Deep margin |

| 1 | 20 | Adenomatoid hyperplasia/LGD | Adenocarcinoma/poorly differentiated | Muscularis propria | (-) | (+) |

| 2 | 17 | Tubular adenoma | Tubular adenoma/HGD | Mucosa | (-) | (-) |

| 3 | 25 | Adenomatoid hyperplasia | Tubulovillous adenoma/HGD | Mucosa | (-) | (-) |

| 4 | 35 | Inflammation/adenomatoid hyperplasia | Hamartomatous polyp/LGD | Mucosa | (-) | (-) |

| 5 | 15 | Inflammation/HGD/field cancerization? | Atypical juvenile polyposis/tubulovillous adenoma/HGD/field cancerization | Muscularis mucosae and submucosa | (-) | (-) |

Endoscopic polypectomy is considered a first-line approach for selected patients with papillary tumors. Compared with traditional surgery, this technique has obvious advantages in procedure-related risks, but it is technically challenging and is not without complications[12,13].

With the application of endoscopic piecemeal resection, balloon traction, and the popularization of the concept of “total biopsy”, more and more lesions previously considered unsuitable for endoscopic resection, such as larger size, intraductal growth, suspected malignant and even early cancerous papillary lesions, can now be treated with EP[4-8,14]. In the present study, the median size of the tumors was 20 mm and final histopathological diagnoses of the endoscopic specimens were one tubular adenoma with HGD, one tubulovillous adenoma with LGD, one hamartomatous polyp with HGD, one poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma and one atypical juvenile polyposis with tubulovillous adenoma, HGD and field cancerization invading the muscularis mucosae and submucosa. EP was technically feasible in all five patients, and four of these patients achieved en bloc excision and curative resection. However, compared with final pathology, the biopsy pathological diagnosis was underestimated in three of five cases and only two cases showed consistency in our study. It was reported that the diagnostic accuracy of ampullary biopsy is 40% to 88%, while 16% to 60% cancer patients are false negative, indicating that an accurate differentiation of malignant from benign lesions cannot be based solely on a pathologic report of biopsy specimens[3,15-19].

The complexity of the EP technique and the expansion of the depth and breadth of resection may lead to an increase in the incidence of complications. EP-related complications were divided into early (acute pancreatitis, bleeding, and perforation) and late (post-ESP stenosis) complications. The overall reported incidence of complications was between 8% and 36%, and the most common complications are acute pancreatitis (5%-15%) and bleeding (2%-20%)[3,4,20,21]. Most episodes of acute pancreatitis are mild and can be relieved by conservative treatment, while most episodes of bleeding can be controlled by conservative treatment and endoscopic hemostasis. The rate of pancreatic and/or biliary ductal stenosis varies between 0%-8%[22], and can be treated by sphincterotomy, stent placement, and balloon dilation. Delayed perforation after EP is a rare (0%-4%)[22] but fatal complication. Due to the anatomical location, duodenal surgery as a treatment for delayed perforation is highly invasive, while non-surgical treatment may require long-term conservative treatment for recovery[23]. Therefore, it is important to prevent the occurrence of delayed perforation after EP.

Tumor location distal to the main papilla is significantly associated with the occurrence of delayed perforation[23]. After endoscopic resection, the duodenal ulcer is directly exposed to bile and pancreatic juice, resulting in delayed perforation[9,10]. Therefore, shunting bile and pancreatic juice to avoid erosion of the duodenal ulcer may be an option to prevent delayed perforation after EP. In this study, we placed overlength biliary and pancreatic stents in five patients with propria muscle exposure or injury after EP to drain bile and pancreatic juice to the proximal jejunum. In order to achieve radical resection, we expanded the depth and breadth of resection in EP, which may be an important cause of exposure or injury of muscularis propria. Endoscopic overlength stents placement was technically feasible in all five patients. There were no stent-related complications, but one papillectomy-related complication (mild acute pancreatitis) occurred without any episodes of bleeding, perforation, cholangitis or late-onset duct stenosis during a mean follow-up period of 12 mo.

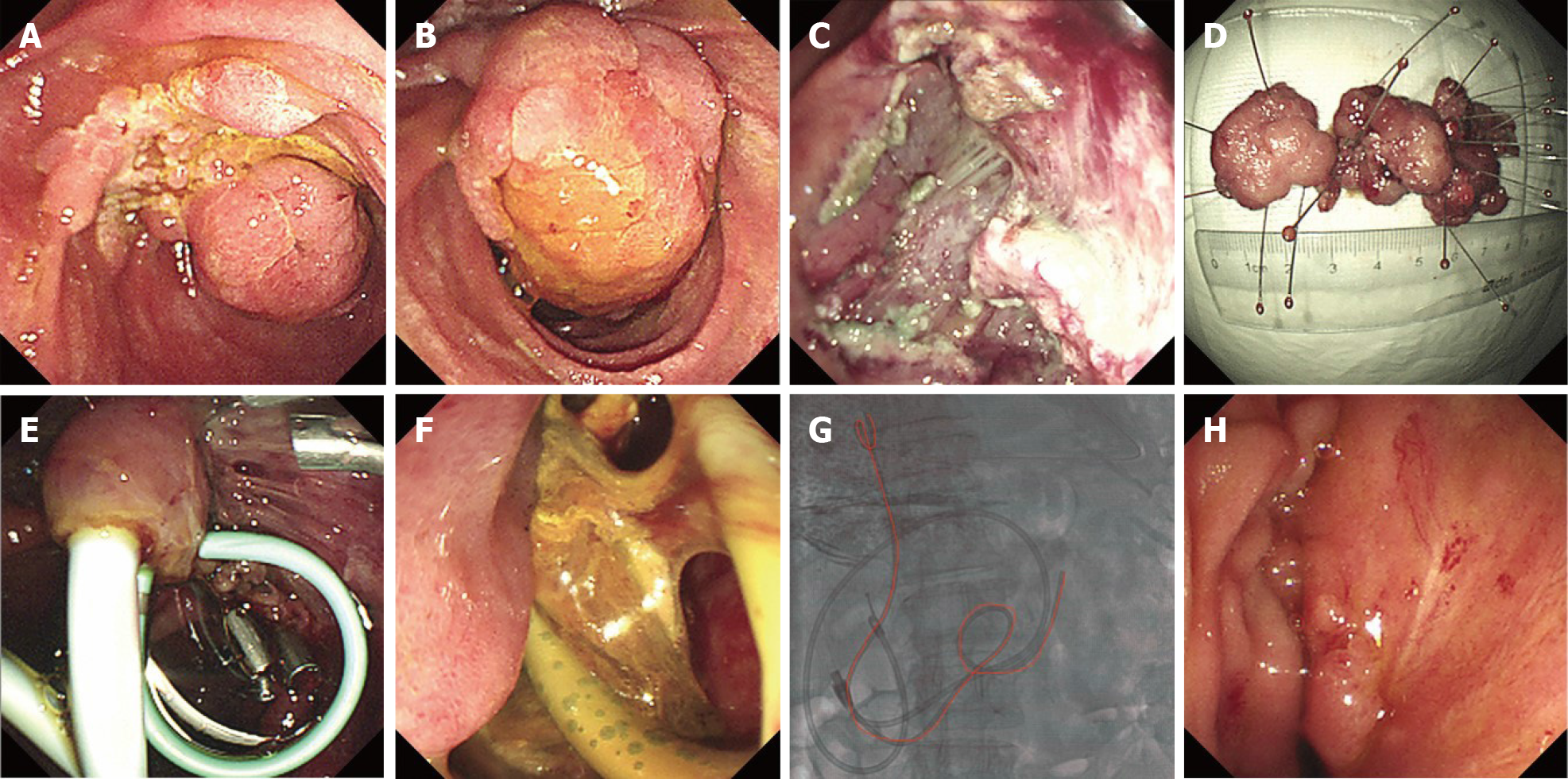

Overlength stents placement can also play a role in the adjuvant treatment of delayed perforation after EP. In June 2018 and October 2018, we treated two cases of major duodenal papilla lesions by EP: One case with a 7 cm villous tubular adenoma with HGD (Figure 2A, B and D), and one case with a 3 cm tubular adenoma. The former lesion was resected in a piecemeal fashion, and the latter was resected in an en bloc manner. Although complete resection was achieved in both cases, there was obvious exposure of the muscularis propria (Figure 2C). We placed conventional biliary and pancreatic plastic stents immediately and covered the exposed wound with fibrin glue after EP (Figure 2E), but delayed perforation still occurred (Figure 2F). Following the occurrence of delayed perforation, we used a multidisciplinary approach involving a combination of multiple clipping, fibrin glue filling, percutaneous drainage, and endoscopic nasobiliary duct drainage tube insertion (which was removed a few days later, due to nasopharyngeal discomfort). However, the perforation failed to heal for a long time. Later, we used an overlength biliary stent to drain bile to the proximal jejunum (Figure 2G), which finally promoted rapid healing of the perforation (Figure 2H).

The main limitations of this study were the small number of cases and the relatively short follow-up time, which limits the statistical power of the results. Given these limitations, the current results on the association between the incidence of complications and EP should be interpreted with caution. In addition, this is a retrospective, uncontrolled, single-center study, involving only cases of muscularis propria exposure or injury, so there is an obvious selection bias. Nonetheless, this is the first study to focus on endoscopic pancreaticobiliary drainage with overlength stents to prevent delayed perforation after EP.

In conclusion, overlength biliary and pancreatic stents placement after EP is a feasible, useful and safe technique to prevent papillectomy-related complications, especially delayed perforation. However, due to the unique physiology and intricate anatomy of the duodenum, it is often difficult and time-consuming to place the distal ends of overlength stents into the jejunum. In view of the limited number of patients and the short-term follow-up, a further larger study with long-term follow-up is needed to confirm our results.

Endoscopic papillectomy (EP) is rapidly replacing traditional surgical resection and is a less invasive procedure for the treatment of duodenal papillary tumors in selected patients. With the expansion of indications, concerns regarding EP include not only technical difficulties, but also the risk of complications, especially delayed duodenal perforation. Delayed perforation after EP is a rare but fatal complication. Exposure of the artificial ulcer to bile and pancreatic juice is considered to be one of the causes of delayed perforation after EP. To drain bile and pancreatic juice away from the wound may help to prevent delayed perforation.

Although the application of an endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) tube can achieve external drainage of bile, it is generally unable to drain pancreatic juice at the same time and may cause stress due to nasopharyngeal discomfort; while the conventional plastic biliary and pancreatic stents cannot drain bile and pancreatic juice a distance due to their limited length. These drainage methods cannot avoid erosion of the artificial ulcer by bile and/or pancreatic juice after EP. Therefore, we modified the ENBD tubes into overlength biliary and pancreatic stents to drain bile and pancreatic juice to the proximal jejunum.

The present study aimed to evaluate the feasibility and safety of placing overlength biliary and pancreatic stents after EP.

This is a single-center, retrospective study. Five patients with exposure or injury of the muscularis propria after EP were included. A 7-Fr overlength biliary stent and a 7-Fr overlength pancreatic stent, modified by an ENBD tube, were placed in the common bile duct and pancreatic duct, respectively, and the bile and pancreatic juice were drained to the proximal jejunum.

EP and overlength stents placement were technically feasible in all five patients, with an average operative time of 63.0 ± 5.6 min. Of the five lesions (median size 20 mm, range 15-35 mm), en bloc excision and curative resection was achieved in four. The final histopathological diagnoses of the endoscopic specimens were one tubular adenoma with high-grade dysplasia (HGD), one tubulovillous adenoma with low-grade dysplasia, one hamartomatous polyp with HGD, one poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma and one atypical juvenile polyposis with tubulovillous adenoma, HGD and field cancerization invading the muscularis mucosae and submucosa. There were no stent-related complications, but one papillectomy-related complication (mild acute pancreatitis) occurred without any episodes of bleeding, perforation, cholangitis or late-onset duct stenosis.

For patients with exposure or injury of muscularis propria after EP, the placement of overlength biliary and pancreatic stents is a feasible and useful technique to prevent delayed perforation.

Overlength biliary and pancreatic stents placement after EP is a feasible, useful and safe technique to prevent papillectomy-related complications, especially delayed perforation, in selected patients by experienced endoscopists. However, due to the unique physiology and intricate anatomy of the duodenum, it is often difficult and time-consuming to place the distal ends of overlength stents into the jejunum. In view of the limited number of patients and the short-term follow-up, a further larger prospective study with long-term follow-up is needed to confirm our results.

We are indebted to Dr. Zhang DW for the helpful suggestions and language polishing of this paper.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: American Gastroenterological Association, No. 0000915672.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Masuda A S-Editor: Huang P L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Bohnacker S, Soehendra N, Maguchi H, Chung JB, Howell DA. Endoscopic resection of benign tumors of the papilla of vater. Endoscopy. 2006;38:521-525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | El Hajj II, Coté GA. Endoscopic diagnosis and management of ampullary lesions. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2013;23:95-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Li S, Wang Z, Cai F, Linghu E, Sun G, Wang X, Meng J, Du H, Yang Y, Li W. New experience of endoscopic papillectomy for ampullary neoplasms. Surg Endosc. 2019;33:612-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ito K, Fujita N, Noda Y, Kobayashi G, Obana T, Horaguchi J, Koshita S, Kanno Y, Ogawa T, Kato Y, Yamashita Y. Impact of technical modification of endoscopic papillectomy for ampullary neoplasm on the occurrence of complications. Dig Endosc. 2012;24:30-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Aiura K, Imaeda H, Kitajima M, Kumai K. Balloon-catheter-assisted endoscopic snare papillectomy for benign tumors of the major duodenal papilla. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:743-747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kim HK, Lo SK. Endoscopic approach to the patient with benign or malignant ampullary lesions. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2013;23:347-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Petrone G, Ricci R, Familiari P, Inzani F, Matsuoka M, Mutignani M, Delle Fave G, Costamagna G, Rindi G. Endoscopic snare papillectomy: a possible radical treatment for a subgroup of T1 ampullary adenocarcinomas. Endoscopy. 2013;45:401-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ogawa T, Ito K, Fujita N, Noda Y, Kobayashi G, Horaguchi J, Koshita S, Kanno Y, Masu K, Ishii S. Endoscopic papillectomy as a method of total biopsy for possible early ampullary cancer. Dig Endosc. 2012;24:291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Honda T, Yamamoto H, Osawa H, Yoshizawa M, Nakano H, Sunada K, Hanatsuka K, Sugano K. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial duodenal neoplasms. Dig Endosc. 2009;21:270-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Shinoda M, Makino A, Wada M, Kabeshima Y, Takahashi T, Kawakubo H, Shito M, Sugiura H, Omori T. Successful endoscopic submucosal dissection for mucosal cancer of the duodenum. Dig Endosc. 2010;22:49-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bohnacker S, Seitz U, Nguyen D, Thonke F, Seewald S, deWeerth A, Ponnudurai R, Omar S, Soehendra N. Endoscopic resection of benign tumors of the duodenal papilla without and with intraductal growth. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:551-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Dubois M, Labgaa I, Dorta G, Halkic N. Endoscopic and surgical ampullectomy for non-invasive ampullary tumors: Short-term outcomes. Biosci Trends. 2017;10:507-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ochiai Y, Kato M, Kiguchi Y, Akimoto T, Nakayama A, Sasaki M, Fujimoto A, Maehata T, Goto O, Yahagi N. Current Status and Challenges of Endoscopic Treatments for Duodenal Tumors. Digestion. 2019;99:21-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hopper AD, Bourke MJ, Williams SJ, Swan MP. Giant laterally spreading tumors of the papilla: endoscopic features, resection technique, and outcome (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:967-975. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Stolte M, Pscherer C. Adenoma-carcinoma sequence in the papilla of Vater. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:376-382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Irani S, Arai A, Ayub K, Biehl T, Brandabur JJ, Dorer R, Gluck M, Jiranek G, Patterson D, Schembre D, Traverso LW, Kozarek RA. Papillectomy for ampullary neoplasm: results of a single referral center over a 10-year period. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:923-932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yamaguchi K, Enjoji M, Kitamura K. Endoscopic biopsy has limited accuracy in diagnosis of ampullary tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:588-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kang SH, Kim KH, Kim TN, Jung MK, Cho CM, Cho KB, Han JM, Kim HG, Kim HS. Therapeutic outcomes of endoscopic papillectomy for ampullary neoplasms: retrospective analysis of a multicenter study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017;17:69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Seifert E, Schulte F, Stolte M. Adenoma and carcinoma of the duodenum and papilla of Vater: a clinicopathologic study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:37-42. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Patel R, Varadarajulu S, Wilcox CM. Endoscopic ampullectomy: techniques and outcomes. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:8-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Norton ID, Gostout CJ, Baron TH, Geller A, Petersen BT, Wiersema MJ. Safety and outcome of endoscopic snare excision of the major duodenal papilla. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:239-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Han J, Kim MH. Endoscopic papillectomy for adenomas of the major duodenal papilla (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:292-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Inoue T, Uedo N, Yamashina T, Yamamoto S, Hanaoka N, Takeuchi Y, Higashino K, Ishihara R, Iishi H, Tatsuta M, Takahashi H, Eguchi H, Ohigashi H. Delayed perforation: a hazardous complication of endoscopic resection for non-ampullary duodenal neoplasm. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:220-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |