Published online Nov 28, 2020. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i44.7005

Peer-review started: May 5, 2020

First decision: June 4, 2020

Revised: June 10, 2020

Accepted: September 22, 2020

Article in press: September 22, 2020

Published online: November 28, 2020

Processing time: 206 Days and 3 Hours

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with tumor thrombus in the bile duct (BDTT) is easily misdiagnosed or mistreated due to the clinicopathological diversity of the thrombus and its relationship with primary lesions.

To propose a new classification for HCC with BDTT in order to guide its diagnosis and treatment.

A retrospective review of the diagnosis and treatment experience regarding seven typical HCC patients with BDTT between January 2010 and December 2019 was conducted.

BDTT was preoperatively confirmed by computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging in only four patients. Three patients with recurrent HCC and one patient with first-occurring HCC had no visible intrahepatic tumors; of these, misdiagnosis occurred in two patients, and three patients died. One patient was mistreated as having common bile duct stones, and another patient with a history of multiple recurrent HCC was misdiagnosed until obvious biliary dilation could be detected. Only one patient who received hepatectomy accompanied by BDTT extraction exhibited disease-free survival during the follow-up period. A new classification was proposed for HCC with BDTT as follows: HCC with microscopic BDTT (Type I); resectable primary or recurrent HCC mass in the liver with BDTT (Type II); BDTT without an obvious HCC mass in the liver (Type III) and BDTT accompanied with unresectable intra- or extrahepatic HCC lesions (Type IV).

We herein propose a new classification system for HCC with BDTT to reflect its pathological characteristics and emphasize the significance of primary tumor resectability in its treatment.

Core Tip: Hepatocellular carcinoma with a tumor thrombus in the bile duct is easily misdiagnosed or mistreated. We herein review our diagnosis and treatment experiences and propose a new classification for this complicated disease based on its clinicopathological features.

- Citation: Zhou D, Hu GF, Gao WC, Zhang XY, Guan WB, Wang JD, Ma F. Hepatocellular carcinoma with tumor thrombus in bile duct: A proposal of new classification according to resectability of primary lesion. World J Gastroenterol 2020; 26(44): 7005-7021

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v26/i44/7005.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v26.i44.7005

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with tumor thrombus in the bile duct (BDTT), a special pathological morphology in HCC, was gradually discovered and has attracted attention since the middle of the last century. BDTT was first reported by Mallory et al[1] in 1947. In 1975, Lin et al[2] named BDTT “Icteric-Type Hepatocarcinoma” on the basis of the symptoms of jaundice. Prior to the 1990s, the incidence of HCC combined with BDTT was quite low, accounting for only 0.53% to 2% of all HCC cases. Recently, some studies have reported that 12.9% of all HCC patients have BDTT, and many among them do not have gross jaundice at first diagnosis[3-5]. In terms of prognosis, the median tumor-free survival of patients with BDTT is 8 mo and that of patients without BDTT is 33 mo. The 1-, 3-, and 5-yr cumulative tumor-free survival rates of HCC patients with and without BDTT are 37.2%, 11.5%, and 0% and 59.4%, 47.9%, and 24.5%, respectively. The 5-yr survival of HCC patients with BDTT is 20 mo less on average than those without BDTT[6,7].

Pathologically, BDTT is mostly formed in the background liver of nodular cirrhosis caused by hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus(HCV). In general, BDTT is a purple-black, soft thrombus without dense adhesion to the bile duct wall, which is the pathological basis of the commonly used bile duct thrombus extraction in clinical practice[8,9]. There are two pathological types of BDTT. The first is mainly composed of cancer cells, which are yellow-gray in color after fixation. The other type, called ”cancerous thrombosis,” is composed of blood clots and cancer cells caused by invasive hemorrhage of the bile duct wall. Regarding the features of primary HCC lesions that cause BDTT, the tumors are mostly diffuse or invasive with moderate or poor differentiation, no capsule or only partial capsule, and strong invasiveness, which causes BDTT formation. It is worth noting that some primary HCC lesions are too small to be detected by preoperative imaging examinations.

Notably, there are two kinds of BDTT for which the alert should be triggered: (1) BDTT without a macroscopically visible first-occurring HCC mass; and (2) BDTT as the first and only manifestation of recurrent HCC with no liver-occupying lesion. Nonspecific clinical and laboratory findings, such as slight cholangitis without jaundice, normal alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) value and localized bile duct dilatation, are not uncommon among patients with the abovementioned two kinds of HCC with BDTT[10]. Because of insufficient vigilance in this disease, BDTT easily tends to be misdiagnosed as cholangitis or choledocholithiasis, especially in patients with a history of radical hepatectomy with no abnormal clinical manifestations during their follow-up period.

To date, most of the published papers regarding HCC with BDTT have focused on its surgical procedures, but very few have discussed the relationships between the primary tumors and thrombus from the etiological and pathological perspective, which might be more critical for the diagnosis and treatment. In the present retrospective study, we reviewed and analyzed our diagnosis and treatment experience regarding seven HCC patients with BDTT, including misdiagnosed cases. We also propose a new classification for HCC with BDTT based on its clinic-pathological features.

Seven patients diagnosed with HCC with BDTT were admitted to our department between January 2010 and December 2019 (Table 1). Among them, only three were referred to the outpatient clinic due to visible jaundice. Three patients received hepatectomy for first-occurring HCC lesions, and BDTT was treated by liver resection, extrahepatic bile duct resection, and choledocholithotomy with thrombus extraction. Then, the BDTT was extracted through choledocholithotomy without further tumor resection in three patients due to extensive intra- and extrahepatic metastatic tumors or undetectable HCC lesions. The last remaining case was clinically confirmed as HCC with BDTT by the history of multiple recurrent HCC, the rising value of AFP > 700 ng/mL, and distal intrahepatic bile duct dilation.

| No. | Sex | Age | Jaundice before treatment for BDTT | AFP, ng/mL | BDTT with first occurring/recurrent HCC or metastasis | BDTT with PVTT | History of hepatectomy before BDTT diagnosed | Time interval from hepatectomy to diagnosis of BDTT | Location of BDTT | Classification | Treatment for BDTT | Survival state during follow-up | ||

| T-bil, μmol/L | D-bil, μmol/L | Satoh | Ours | |||||||||||

| 1 | M | 58 | 16.0 | 0.0 | 9420.00 | fo-HCC | Yes | / | / | IBD | N/A4 | I | Resected with HCC | Dead |

| 2 | M | 68 | 53.1 | 34.4 | 97.23 | rHCC | No | Yes | 6 yr | CBD | 3 | III | Extraction | Dead |

| 3 | M | 70 | 16.7 | 6.2 | 737.00 | rHCC/LgMT/ACMT | Yes | Yes | 19 mo19 mo2 | IBD | N/A5 | IV | Lenvatinib+Sintilizumab | Alive with tumor |

| 4 | M | 65 | 145.5 | 76.7 | 176.54 | fo-HCC | No | / | / | LHD/RHD/CHD | 2 | IIa | Extrahepatic bile duct resection3 | Dead |

| 5 | M | 75 | 146.9 | 51.90 | 1.37 | No | No | / | / | CBD | 3 | III | Extraction | Alive with tumor |

| 6 | M | 68 | 224.1 | 183.8 | 1.84 | rHCC/LNMT/ACMT | No | Yes | 2 mo | CBD | 3 | III | Extraction | Dead |

| 7 | F | 58 | 37.2 | 27.6 | 45.22 | fo-HCC | No | / | / | CBD | 3 | IIb | Extraction | DFS |

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval for the present study was granted by Xinhua Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University, School of Medicine (Shanghai, China). The study was strictly in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and International Ethical Guidelines for Health-related Research Involving Humans. All the included patients signed an informed consent form. A multidisciplinary team made up of hepatobiliary surgeons, radiologists, oncologists, gastroenterologists, and pathologists selected candidates for the treatment together.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Patients diagnosed as HCC with BDTT based on pathology or typical imaging findings; and (2) Patients with well-defined outcomes including total hospital stay and follow-up results of survival related data.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Patients diagnosed as non-HCC tumors or other diseases causing thrombus in biliary ducts; (2) Patients diagnosed as primary biliary tumors; (3) Patients diagnosed as mixed tumors of hepatobiliary systems with thrombus in the bile ducts; and (4) Patients who did not have well-defined outcomes or follow-up results.

All patients received serum AFP detection and imaging tests, including multidetector computed tomography scans and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) was performed for patients who were suspected to have metastasis. The imaging data (images and diagnostic reports) were reviewed independently by two experienced radiologists, and a consensus was reached upon confirmation of the main findings.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) was performed when patients had difficulty in diagnosis of BDTT or biliary drainage was indicated. ERCP: Side-viewing duodenoscope (JF-260V, Olympus Medical System, Tokyo, Japan) was inserted through the mouth and passed all the way to the duodenum. After the ampulla of Vater was confirmed by camera, catheters and cannulas were passed through the duodenoscope and then into the biliary tree at the ampulla of Vater. Radiographic contrast material (Diatrizoate meglumine, Xudong Haipu Pharmaceutical Co., LTD, Shanghai, China) was injected so the biliary tree was visualized under X-ray. PTC: The right hepatic duct (RHD) was punctured by a 22G needle (Neff Percutaneous Access Set, Cook Medical LLC, Bloomington, IN, United States). The biliary tree was shown by injecting diatrizoate meglumine (Xudong Haipu Pharmaceutical Co., LTD, Shanghai, China) via the needle. After radiography, an 8.5F external drainage tube (Biliary Drainage Catheter, Cook Medical LLC, Bloomington, IN, United States) was placed in the common bile duct (CBD).

Pathological reports were also performed in a similar way by pathologists. The anatomical location of the BDTT was confirmed and categorized according to the Satoh classification system: Type 1 [BDTT located in the first branch of the hepatic duct but not reaching the confluence of the RHD and left hepatic duct (LHD)]; type 2 (BDTT extending across the confluence of the RHD and LHD); type 3 (BDTT separate from the primary HCC lesion and growth in the CBD)[11].

The patients were requested to be re-examined at outpatient visits every 1-2 mo after surgical treatment by receiving physical examinations, routine full blood counts, liver function tests, tumor marker sets, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)/MRCP with data recorded in the electronic medical record. All of the living patients were followed up until December 2019.

A systematic search was performed for the causes of misdiagnosis and mistreatment of HCC with BDTT using PubMed, Embase, Ovid, and Web of Science independently by two researchers. The relevant studies published from January 2000 until January 2020 were searched and gathered through the following terms: Hepatocellular carcinoma with tumor thrombus in the bile duct, BDTT OR BDT OR bile duct tumor thrombus. Studies that focused on nonprimary hepatocellular carcinoma, did not provide enough information on misdiagnosis or mistreatment of HCC with BDTT, and papers published in languages other than English were excluded.

Patients in this study included 6 men and 1 woman who ranged in age from 58 to 75 years. The clinicopathological characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1. Four patients (No. 1, 4, 5, 6) were positive for HBsAg, HBeAb, and HBcAb, and one patient was positive for HCV-AB-IgG (No. 3). Among them, four patients (No. 1, 4, 5, 7) were pathologically diagnosed with cirrhosis. HBV-DNA was detected by means of fluorescent quantitative PCR for patients with positive HBsAg, and the results showed < 0.5 × 103 cps/mL for all of the patients (Table 2).

| No. | HBsAg | HBsAb | HBeAg | HBeAb | HBcAb | HBcIgM | HCV-AB-IgG | |||||||

| Qualitative | Value (IU/mL) | Qualitative | Value (mIU/mL) | Qualitative | Value (S/CO) | Qualitative | Value (S/CO) | Qualitative | Value (S/CO) | Qualitative | Value (S/CO) | Qualitative | Value (S/CO) | |

| 1 | + | > 250 | - | 0.00 | - | 0.304 | + | 0.02 | + | 13.70 | - | 0.26 | - | 0.02 |

| 2 | - | 0 | - | 4.05 | - | 0.270 | + | 0.02 | + | 8.68 | - | 0.05 | - | 0.09 |

| 3 | - | 0.01 | + | 97.28 | - | 0.397 | + | 0.07 | + | 9.79 | - | 0.14 | + | 1.71 |

| 4 | + | > 250 | - | 0.00 | - | 0.107 | + | 0.04 | + | 15.80 | - | 0.07 | - | 0.01 |

| 5 | + | 16.94 | - | 5.43 | - | 0.317 | + | 0.01 | + | 7.96 | - | 0.15 | - | 0.14 |

| 6 | + | 161.53 | - | 0.19 | - | 0.230 | + | 0.01 | + | 8.46 | - | 0.08 | - | 0.06 |

| 7 | - | 0.02 | - | 0.00 | - | 0.400 | + | 0.09 | + | 13.57 | - | 0.05 | - | 0.03 |

The results of CT or MRI suggested HCC with BDTT for 4 patients (No. 2, 4, 6, 7) as the initial diagnosis. However, the primary HCC lesion of patient No. 1 was misdiagnosed as a gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the stomach. For patient No. 5, BDTT was mistreated as CBD stones by ERCP without a pathological examination at his first admission. Missed diagnosis occurred in one patient (No. 3) who had a history of multiple recurrent HCC.

Patient No. 1 was diagnosed with poor differentiation of massive HCC (8 cm × 6 cm × 6 cm) with microscopic BDTT, portal vein tumor thrombus and gastric invasion (Figure 1, Table 3).

| No. | Pathological characteristics of primary or recurrent HCC lesion when BDTT was diagnosed | Pathological characteristics of BDTT | |||||||||

| Location | Size in cm | Morphology of tumor | Differentiation | Necrosis | Extrahepatic infiltration | Location | Size incm | Infiltration outward bile duct | Differentiation | ||

| Macroscopic | Microscopic | ||||||||||

| 1 | Left lobe | 8 × 6 × 6 | Fish-meat like | Platelet/nested/papillary | Poor | + | Full thickness of the stomach wall | LIBD | MicroscopicBDTT | No | Poor |

| 2 | Cannot be detected | / | / | / | / | / | / | CBD | 5.5 × 4 × 2 | No | Moderate |

| 31 | Cannot be detected | / | / | / | / | / | / | IBD | / | / | / |

| 4 | Right lobe | 9 × 4 × 9 | Fish-meat like | Nodular | Moderate | + | No | LHD/RHD/CHD | 5 × 3 × 3 | Yes | Moderate |

| 52 | Cannot be detected | / | / | / | / | / | / | CBD | 6 × 2 × 2 | No | Poor |

| 62 | Cannot be detected | / | / | / | / | / | / | CBD | 3.5 × 3.5 × 2 | No | Moderate |

| 7 | Right lobe | 7 × 4 × 1 | Fish-meat like | Large area of necrosis | Moderate | + | No | CBD | 3 × 3 × 2 | No | Moderate |

For patient No. 2, recurrence in the form of BDTT in CBD (Satoh’s type 3) without visible intrahepatic HCC mass was diagnosed by PET-CT and percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscopy (PTC) 6 years after his first hepatectomy. A 5.5 cm-long BDTT was extracted from the CBD, and moderately differentiated HCC was confirmed by pathology (Figure 2, Table 3).

Notably, patient No. 3, at 19 mo and 9 mo before BDTT was diagnosed, received hepatectomy for poorly differentiated HCC and resection for a single recurrent tumor located in the abdominal cavity, respectively. Although this patient had a history of multiple recurrent HCC, BDTT located in the left intrahepatic bile duct without a mass-like tumor in the liver was finally diagnosed when the AFP level climbed over 700 ng/mL and obvious biliary dilation and metastatic lesions in the omentum majus and lung could be detected (Figure 3).

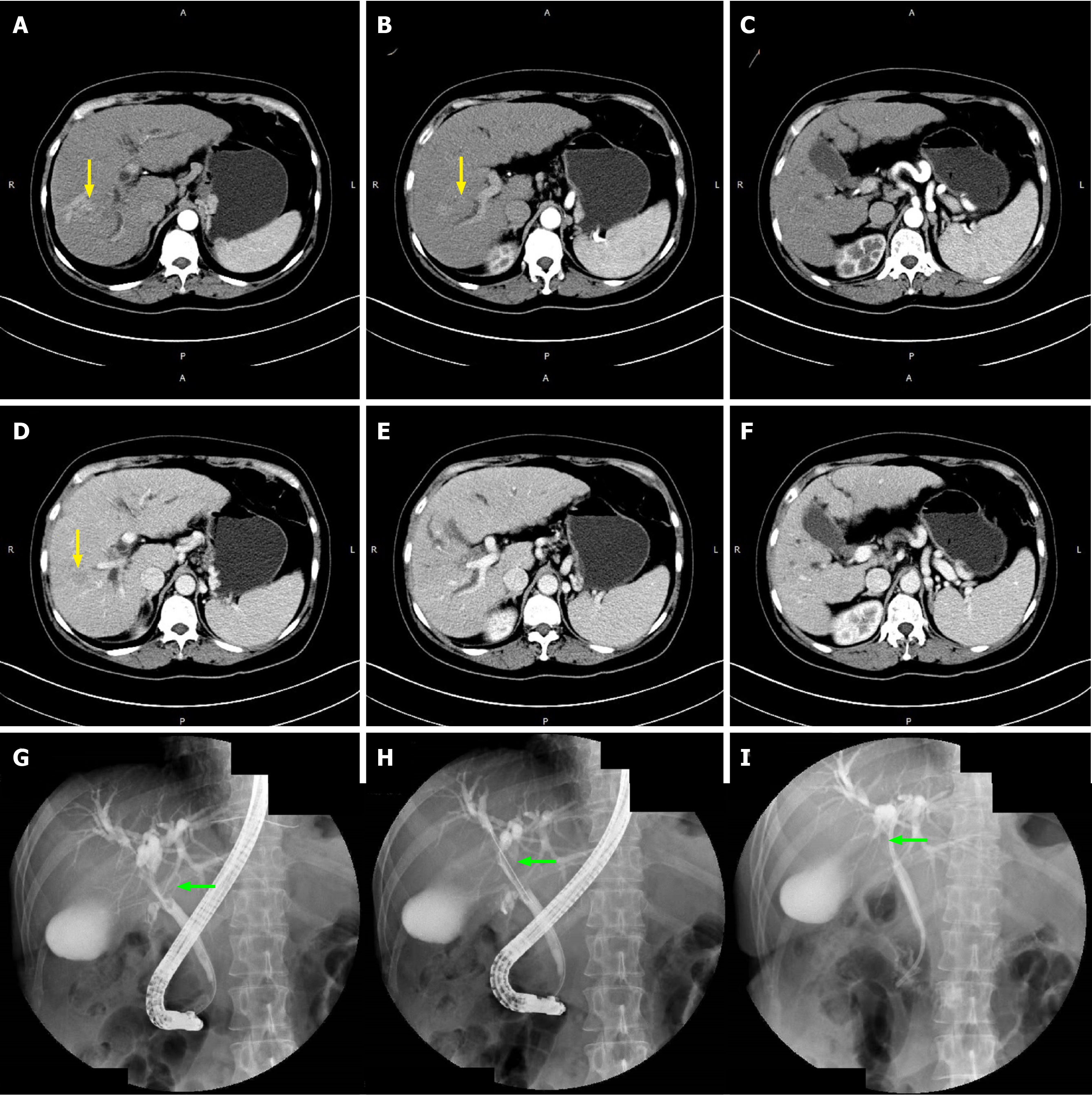

Two patients (No. 5 and 6) were diagnosed with BDTT with invisible first-occurring HCC in the liver. Their thrombi were both located in the CBD (Satoh’s type 3). The AFP values of patients No. 5 and 6 were both within the normal range. This might be the main factor that led to a delay in diagnosis in the above two cases. The extraction of BDTT (moderately differentiated HCC) from CBD was the only choice of surgical treatment for patient No. 6 because recurrent HCC in the celiac lymph nodes and peritoneal metastases had already existed. It was also regrettable to note that BDTT was misdiagnosed as a CBD stone in patient No. 5, whose CT images and AFP did not suggest HCC at his first admission. However, although closely observed during follow-up after ERCP by testing serum tumor markers and imaging detection, BDTT was finally diagnosed as poorly differentiated HCC during CBD exploration at his readmission. At that time, an arterially enhanced mass in the CBD could be detected in CT images (Figure 4). Unfortunately, intrahepatic lesions could not be detected during the operation, and consequently, the patient only received transhepatic arterial chemotherapy and embolization (TACE) after BDTT extraction.

The HCC lesions and BDTTs were both resectable for patients No. 4 and No. 7. The HCC lesion in patient No. 4 was a 9 cm × 4 cm × 9 cm massive tumor occupying the right lobe with a connected thrombus extending across the confluence of the RHD and left hepatic duct (Satoh’s type 2). Radical right hepatectomy combined with extrahepatic bile duct resection was chosen for this patient because the cancerous thrombus infiltrated the outer bile duct wall (Figure 5, Table 3). Patient No. 7, who had obvious signs including elevated AFP levels, a large liver mass (7 cm × 4 cm × 1 cm) on CT scans and a thrombus in the CBD (Satoh’s type 3) confirmed by ERCP, was successfully cured by hepatectomy with thrombus extraction (Figure 6).

Only one patient (No. 7) had disease-free survival after surgery for 60 mo. Four patients (No. 1, 2, 4, 6) died due to multiple recurrent or metastatic tumors in the liver and systemic metastases other than BDTT. Among these cases, multiple intrahepatic metastases occurred in patient No. 1 with microscopic BDTT, while recurrences in a patient with a thrombus infiltrating the CBD (patient No. 4) occurred in the hepatoduodenal ligament as well as the omentum. Patient No. 5 received TACE, while for patient No. 3, lenvatinib + sintilizumab was utilized for adjuvant therapy. The above 2 patients were still alive with tumors during follow-up periods of 1.5 mo and 5 mo, respectively.

Only five retrospective studies met our search criteria (Table 4). Notably, all of the studies were from China[12-16]. The studies included 151 patients with HCC with BDTT who received various treatments from 1984 to 2018. The preoperative diagnostic methods only included ultrasound, CT, MRI, and ERCP. The retrieved data showed that BDTT was most commonly misdiagnosed as choledocholithiasis or cholangiocarcinoma, which occurred in 5.7%-66.7% of the patients. However, none of the included studies mentioned the effect of misdiagnosis on the prognosis of the patients.

| No. | Ref. | Time period | No. of included patients of HCC with BDTT | No. of misdiagnosed patients, % | Diagnostic method | Misdiagnosed as | Treatment | Prognosis |

| 1 | Zhou et al[12], 2020 | 2011/01-2018/08 | 58 | 32 (55.2) | CT | Hilar cholangiocarcinoma | Hepatectomy | DFS: 16.1 mo |

| Hepatectomy with bile duct excision | DFS: 7.3 mo | |||||||

| 2 | Zheng et al[13], 2014 | 2007/01-2012/12 | - | 5 (-) | CT/MRI/ERCP | Choledocholithiasis and cholangitis | ENBD and choledochojejunostomy | POS: 6-22 mo1 alive4 dead |

| thrombus extraction | ||||||||

| ENBD | ||||||||

| 3 | Long et al[14], 2010 | 2000/01-2008/11 | 61 | 4 (66.7)1 | US/CT/MRI/ERCP | Choledocholithiasis and cholangiocarcinoma | Hepatectomy | Not mentioned |

| thrombus extraction | ||||||||

| 4 | Peng et al[15], 2005 | 1984/07-2002/12 | 53 | 3 (5.7) | US/CT/MRI | Hilar cholangiocarcinoma | PTCD + biliary stent | Median survival of 2-17 mo |

| Hepatectomy with thrombus extraction | ||||||||

| TACE | ||||||||

| thrombus extraction | ||||||||

| Hepatectomy | ||||||||

| 5 | Qin et al[16], 2004 | 1987/06-2003/01 | 34 | 9 (26.5) | US/CT | Cholangiocarcinoma | liver resection and thrombus extraction | Survival ≤ 1 yr 10Survival > 1 yr 20Survival > 3 yr 3Survival > 15 yr 1 |

| thrombus extraction combined with TACE |

To date, the greatest challenge of handling HCC with BDTT is how to avoid misdiagnosis of the tumor thrombus rather than the choice of surgical approaches, especially in cases of BDTT without obvious intrahepatic HCC mass. According to our experience and literature review, the major obstacles and loopholes for making correct diagnoses might exist because surgeons are not familiar with the pathophysiological features of HCC with BDTT and because there is relatively low sensitivity of imaging examinations. Unfortunately, in the present study, the initial diagnoses of the 7 included patients were achieved based on imaging examinations, and 3 patients (42.86%) were misdiagnosed and mistreated. Only one patient received ERCP and clarified the range of the thrombus before surgery, but no patient received pathological evidence until the operation was performed. Therefore, to pursue correct diagnosis and R0 resection, a more comprehensive set of diagnostic modalities should be implemented. The key points of making a definite preoperative diagnosis for HCC with BDTT might include: (1) Confirming the location and size of the primary tumor and whether the primary tumor invades the bile duct; (2) Clarifying the extent of BDTT; (3) Acquiring a pathological diagnosis of BDTT before surgical treatment if possible; and (4) Paying more attention to the suggestive role of tumor markers when intrahepatic HCC lesions are hard to detect.

First, understanding the pathophysiological features of HCC with BDTT was helpful to assess clinical signs properly. The mechanisms and hypothesis of the formation of a BDTT are as follows: (1) The primary tumor directly invades the bile duct, and the BDTT is connected with the primary tumor; (2) The primary tumor metastasizes into the biliary system through microvessels and lymphatic vessels; (3) The primary tumor metastasizes through the arteriovenous shunt to the bile duct system; and (4) The primary tumor metastasizes through the nerves around the bile duct[17]. In the latter three mechanisms, there might be a certain distance between the primary tumor and the BDTT, i.e. the bile duct is not directly infiltrated by the tumor. Notably, the primary tumor can invade the bile duct and form a tumor thrombus even when the tumor itself is still minuscule[18].

Second, combined applications of imaging examinations, endoscopy, and pathology might contribute to improving the diagnostic rate of HCC with BDTT. Theoretically, in CT scans, BDTT shows a slightly lower or equal-density soft tissue shadow in the bile duct, which is similar to the original lesion after enhancement. High-medium differentiated tumors may exhibit light-moderate enhancement. For MRI, BDTT shows a heterogeneous or intermittent increased signal on T2-weighted phase imaging or diffusion-weighted imaging compared to that of the surrounding liver parenchyma. There is no significant attenuation of signals in the short time inversion recovery phase. However, in practical use, CT and MRI are not effective enough in diagnosing BDTT and assessing the extent of tumor thrombus progression. This might be due to the imaging findings of tumor thrombi are often intermittent or the density commonly varies greatly. A retrospective study of 392 patients conducted from 1993 to 2011 by Tan et al[19] revealed that HCC with BDTT was easily misdiagnosed by CT or MRI as HCC compressing the hepatic hilum, hilar cholangiocarcinoma, metastatic hepatic cancer with tumor thrombus, bile duct stones, etc. The total misdiagnosis rates of the above diseases were 4.1%, 4.3%, 2.3%, 1.0%, and 3.8%, respectively.

Intraductal ultrasonography (IDUS) might be a good candidate when BDTT is difficult to diagnose by CT or MRI. IDUS can help to determine whether stenosis in the bile duct is caused by intraductally originated neoplasms or extraductal tumor invasion. In patients with BDTT, IDUS showed signs of a ‘polypoid tumor with a narrow base’ and a ‘nodule within a nodule’ with the absence of a ‘papillary-surface pattern’ that were more strongly associated with HCC than with intraductal polypoid-type cholangiocarcinoma[20].

To date, only a few studies have evaluated the effectiveness of preoperative pathological diagnosis of HCC combined with BDTT due to its relatively low incidence rate. As a type of malignant biliary stenosis (cholangiocarcinoma, metastatic liver cancers invading the bile duct and HCC combined with BDTT, etc.), there are three methods for pathological diagnosis of BDTT before surgery: (1) Tissue biopsy, including oral choledochoscopy, peroral cholangioscopy-guided forceps biopsy (POC-FB) and endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy (EUS-FNAB); (2) Biliary tract cytology brushes; and (3) Direct biopsy under cholangiography. In recent years, with clinical application of the SpyGlass system, the ability of pathological diagnosis in the biliary tract has been significantly improved through its three subsystems: Optical probe (SpyGlass); access catheter (SpyScope); and biopsy forceps (SpyBite). A meta-analysis published in 2015 by Navaneethan et al[21] suggested that the sensitivity of SpyBite-based POC-FB is 60.1% for the diagnosis of biliary malignant stenosis, which is much higher than that of cytoplasmic brush (5.8%) and direct biopsy (29.4%). The sensitivity and specificity of SpyBite for diagnosing biliary malignant stenosis were 74.7% and 93.3%, respectively. Regarding the choice of POC-FB and EUS-FNAB, Lee et al[22] recommended EUS-FNAB for BDTT located in the distal part of the CBD, which is closer to the duodenum, while SpyGlass with POC-FB is more advantageous for thrombi in the proximal bile duct.

Third, the sensitivity of AFP for diagnosing HCC is only 33%-65%, and it is also significantly elevated in active hepatitis and cirrhosis. Protein induced by Vitamin K Absence or Antagonist-II (PIVKA II) and hepatoma-specific alpha-fetoprotein (AFP-L3) potentially play a significant role in indicating HCC with BDTT, especially when intrahepatic lesions cannot be detected. PIVKA-II, also known as des gamma-carboxy prothrombin, was first recognized as a tumor marker for HCC in 1984. When compared with AFP, the advantages of PIVKA-II are as follows: (1) PIVKA-II has no correlation but a complementary effect with AFP; (2) PIVKA-II is also not expressed in other malignant tumors but is expressed in up to 91% of HCCs; and (3) The expression level of PIVKA-II is significantly correlated with differentiation, intrahepatic metastasis, tumor metastasis node stage, and recurrence of HCC[23-25]. AFP-L3 is defined as a specific subtype of AFP that binds to Lens culinaris agglutinin with a normal ratio ranging from 0% to 10%. AFP-L3 is effective in differentiating HCC from hepatitis or cirrhosis when the AFP value of the patient is > 50 ng/mL and AFP-L3 accounts for more than 20%[26,27]. For HCC patients with AFP < 20 ng/mL, Choi JY et al[27] reported that the combination of AFP-L3 and PIVKA-II with sensitivity and specificity up to 92.1% and 79.7%, respectively, successfully detected 81.8% of stage I HCC and 86.7% of tumors < 2 cm.

Ueda and Satoh classifications are the two most commonly used typing methods for HCC with BDTT, which are based on the location of the thrombus in the biliary system. However, they did not reflect the whole field of clinicopathological features of HCC with BDTT, which is critical for the diagnosis and treatment. According to our study and literature review, the resectability of intrahepatic HCC lesions and whether the bile duct wall was infiltrated by tumor thrombus might be the two influences on the choice of surgical treatment. In the present study, the 7 cases of HCC with BDTT took many forms but easily fell into 4 types that we identified (Figure 7): Type I: HCC with microscopic BDTT (patient No. 1); Type II: Resectable first-occurring or recurrent HCC mass in the liver with BDTT (patients No. 4, 7); Type III: BDTT without an obvious HCC mass in the liver (patients No. 5, 6); Type IV: BDTT accompanied with unresectable intra- or extrahepatic HCC lesions (patient No. 2), which should be considered as a form of systemic metastases. BDTT can be further divided into two subtypes according to whether tumor cells of the thrombus invade the extrahepatic bile duct wall (e.g., patients No. 4 and No. 7 were categorized as having Type IIIa and Type IIIb, respectively).

For treating BDTT, the controversy mainly lies in the choice of thrombus extraction or choledochotomy for patients without macroscopic bile duct wall invasion. Advocates for choledochotomy suggested that although BDTT could be easily detached, some remaining HCC cells were microscopically observed to infiltrate the full thickness of the bile duct wall and scatter into its peripheral plexus[17]. However, most surgeons believe that it is feasible to perform thrombus extraction if R0 resection of primary HCC could be achieved because metastasis and recurrence rather than BDTT are more important prognostic factors[28,29]. In addition, it is also advantageous to preserve the extrahepatic bile duct so that recurrent tumors can be treated by TACE. Therefore, thrombus extraction might be reasonable, but choledochoscopy should be performed to confirm that there are no tumor residues.

The treatment for patients with BDTT without an obvious HCC mass (abovementioned proposal classification of type III) was another pain point due to a recurrence rate up to 80% after the first treatment with a survival period ranging from only 6 mo to 22 mo[10]. Comprehending the history of recurrent cholangiolithiasis, combined applications of IDUS, endoscopy with preoperative pathology, and intraoperative ultrasound might help to improve its diagnostic rate, but there has been very little related experience until now. Successful early detection of recurrence depends on the implementation of close follow-up after the first treatment. Adjuvant therapies, such as TACE, radiofrequency ablation, and targeted therapy, can improve the prognosis to a certain degree.

In conclusion, BDTT is a special pathological morphology of HCC that is easily misdiagnosed as various benign and malignant hepatobiliary diseases. Routine imaging examinations such as CT or MRI are sometimes insufficient to provide diagnostic evidence. We proposed a new classification for HCC with BDTT in order to reflect its pathological characteristics and emphasize the significance of primary tumor resectability in its treatment. More attention should be paid to different clinical patterns of this disease, especially those without visible HCC mass in the liver.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with bile duct tumor thrombus (BDTT) is easily misdiagnosed or mistreated due to the clinicopathological diversity of the thrombus and its relationship with primary lesions.

To date, most of the published papers regarding HCC with BDTT have focused on its surgical procedures, but very few have discussed the relationships between the primary tumors and thrombus from the etiological and pathological perspective, which might be more critical for the diagnosis and treatment.

In the present retrospective study, we reviewed and analyzed our diagnosis and treatment experience regarding seven HCC patients with BDTT, including misdiagnosed cases. We also propose a new classification for HCC with BDTT based on its clinicopathological features.

A retrospective review of the diagnosis and treatment experience regarding seven typical HCC patients with BDTT between January 2010 and December 2019 was conducted.

BDTT was preoperatively confirmed by computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging in only four patients. Three patients with recurrent HCC and one patient with first-occurring HCC had no visible intrahepatic tumors; of these, misdiagnosis occurred in two patients, and three patients died. One patient was mistreated as having common bile duct stones, and another patient with a history of multiple recurrent HCC was misdiagnosed until obvious biliary dilation could be detected. Only one patient who received hepatectomy accompanied by BDTT extraction exhibited disease-free survival during the follow-up period. A new classification was proposed for HCC with BDTT as follows: HCC with microscopic BDTT (Type I); resectable primary or recurrent HCC mass in the liver with BDTT (Type II); BDTT without an obvious HCC mass in the liver (Type III); and BDTT accompanied with unresectable intra- or extrahepatic HCC lesions (Type IV).

We herein propose a new classification system for HCC with BDTT to reflect its pathological characteristics and emphasize the significance of primary tumor resectability in its treatment.

The classification system and its guiding significance in the treatment of HCC with BDTT.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Athyros VG, Song MJ, Tomizawa M S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Mallory TB, Castleman B, Parris EE. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. N Eng J Med. 1947;237:673-676. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lin TY, Chen KM, Chen YR, Lin WS, Wang TH, Sung JL. Icteric type hepatoma. Med Chir Dig. 1975;4:267-270. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Navadgi S, Chang CC, Bartlett A, McCall J, Pandanaboyana S. Systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes after liver resection in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with and without bile duct thrombus. HPB (Oxford). 2016;18:312-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Huang GT, Sheu JC, Lee HS, Lai MY, Wang TH, Chen DS. Icteric type hepatocellular carcinoma: revisited 20 years later. J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:53-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ueda M, Takeuchi T, Takayasu T, Takahashi K, Okamoto S, Tanaka A, Morimoto T, Mori K, Yamaoka Y. Classification and surgical treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with bile duct thrombi. Hepatogastroenterology. 1994;41:349-354. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Yang X, Qiu Z, Ran R, Cui L, Luo X, Wu M, Tan WF, Jiang X. Prognostic importance of bile duct invasion in surgical resection with curative intent for hepatocellular carcinoma using PSM analysis. Oncol Lett. 2018;16:3593-3602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Dong W, Zhang T, Wang ZG, Liu H. Clinical outcome of small hepatocellular carcinoma after different treatments: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:10174-10182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wang JB, He ZP. The clinical and pathological study of hepatocellular carcinoma invading on the bile duct [Article in Chinese]. Zhonghua Putongwaike Zazhi. 2000;15:676-678. |

| 9. | Qin L, Ma Z, Tang Z. [Diagnosis and treatment of bile duct tumor thrombus in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma]. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2000;22:418-420. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Kim JM, Kwon CH, Joh JW, Sinn DH, Park JB, Lee JH, Kim SJ, Paik SW, Park CK, Yoo BC. Incidental microscopic bile duct tumor thrombi in hepatocellular carcinoma after curative hepatectomy: a matched study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Satoh S, Ikai I, Honda G, Okabe H, Takeyama O, Yamamoto Y, Yamamoto N, Iimuro Y, Shimahara Y, Yamaoka Y. Clinicopathologic evaluation of hepatocellular carcinoma with bile duct thrombi. Surgery. 2000;128:779-783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhou X, Wang J, Tang M, Huang M, Xu L, Peng Z, Li ZP, Feng ST. Hepatocellular carcinoma with hilar bile duct tumor thrombus versus hilar Cholangiocarcinoma on enhanced computed tomography: a diagnostic challenge. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wu Z, Guo K, Sun H, Yu L, Lv Y, Wang B. Caution for diagnosis and surgical treatment of recurrent cholangitis: lessons from 5 cases of bile duct tumor thrombus without a detectable intrahepatic tumor. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014;93:e80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Long XY, Li YX, Wu W, Li L, Cao J. Diagnosis of bile duct hepatocellular carcinoma thrombus without obvious intrahepatic mass. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4998-5004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Peng BG, Liang LJ, Li SQ, Zhou F, Hua YP, Luo SM. Surgical treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma with bile duct tumor thrombi. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:3966-3969. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Qin LX, Ma ZC, Wu ZQ, Fan J, Zhou XD, Sun HC, Ye QH, Wang L, Tang ZY. Diagnosis and surgical treatments of hepatocellular carcinoma with tumor thrombosis in bile duct: experience of 34 patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:1397-1401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Kojiro M, Kawabata K, Kawano Y, Shirai F, Takemoto N, Nakashima T. Hepatocellular carcinoma presenting as intrabile duct tumor growth: a clinicopathologic study of 24 cases. Cancer. 1982;49:2144-2147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Jang YR, Lee KW, Kim H, Lee JM, Yi NJ, Suh KS. Bile duct invasion can be an independent prognostic factor in early stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Korean J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2015;19:167-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tan WF, Ran RZ, Yang HY, Liu SY, Wu MC. Misdiagnosis analysis of hepatocellular carcinoma combined with bile duct tumor thrombi [Article in Chinese]. Di’er Junyi Daxue Xuebao. 2013;34:411-415. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tamada K, Isoda N, Wada S, Tomiyama T, Ohashi A, Satoh Y, Ido K, Sugano K. Intraductal ultrasonography for hepatocellular carcinoma with tumor thrombi in the bile duct: comparison with polypoid cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:801-805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Navaneethan U, Hasan MK, Lourdusamy V, Njei B, Varadarajulu S, Hawes RH. Single-operator cholangioscopy and targeted biopsies in the diagnosis of indeterminate biliary strictures: a systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 82: 608-614. e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lee YN, Moon JH, Choi HJ, Kim HK, Lee HW, Lee TH, Choi MH, Cha SW, Cho YD, Park SH. Tissue acquisition for diagnosis of biliary strictures using peroral cholangioscopy or endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration. Endoscopy. 2019;51:50-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Tang W, Miki K, Kokudo N, Sugawara Y, Imamura H, Minagawa M, Yuan LW, Ohnishi S, Makuuchi M. Des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin in cancer and non-cancer liver tissue of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2003;22:969-975. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Koike Y, Shiratori Y, Sato S, Obi S, Teratani T, Imamura M, Yoshida H, Shiina S, Omata M. Des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin as a useful predisposing factor for the development of portal venous invasion in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective analysis of 227 patients. Cancer. 2001;91:561-569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Taketomi A, Sanefuji K, Soejima Y, Yoshizumi T, Uhciyama H, Ikegami T, Harada N, Yamashita Y, Sugimachi K, Kayashima H, Iguchi T, Maehara Y. Impact of des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin and tumor size on the recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after living donor liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2009;87:531-537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Taketa K, Endo Y, Sekiya C, Tanikawa K, Koji T, Taga H, Satomura S, Matsuura S, Kawai T, Hirai H. A collaborative study for the evaluation of lectin-reactive alpha-fetoproteins in early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1993;53:5419-5423. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Lim TS, Kim DY, Han KH, Kim HS, Shin SH, Jung KS, Kim BK, Kim SU, Park JY, Ahn SH. Combined use of AFP, PIVKA-II, and AFP-L3 as tumor markers enhances diagnostic accuracy for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:344-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Hasegawa K, Yamamoto S, Inoue Y, Shindoh J, Aoki T, Sakamoto Y, Sugawara Y, Kokudo N, Makuuchi M. Hepatocellular Carcinoma With Bile Duct Tumor Thrombus: Extrahepatic Bile Duct Preserving or Not? Ann Surg. 2017;266:e63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 29. | Wang DD, Wu LQ, Wang ZS. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma with bile duct tumor thrombus after R0 resection: a matched study. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2016;15:626-632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |