Published online Oct 28, 2020. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i40.6260

Peer-review started: May 26, 2020

First decision: June 19, 2020

Revised: September 16, 2020

Accepted: September 25, 2020

Article in press: September 25, 2020

Published online: October 28, 2020

Processing time: 154 Days and 12.6 Hours

Bowel preparation in children can be challenging.

To describe the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of sodium picosulfate, magnesium oxide, and citric acid (SPMC) bowel preparation in children.

Phase 3, randomized, assessor-blinded, multicenter study of low-volume, divided dose SPMC enrolled children 9-16 years undergoing elective colonoscopy. Participants 9-12 years were randomized 1:1:1 to SPMC ½ dose × 2, SPMC 1 dose × 2, or polyethylene glycol (PEG). Participants 13-16 years were randomized 1:1 to SPMC 1 dose × 2 or PEG. PEG-based bowel preparations were administered per local protocol. Primary efficacy endpoint for quality of bowel preparation was responders (rating of ‘excellent’ or ‘good’) by modified Aronchick Scale. Secondary efficacy endpoint was participant’s tolerability and satisfaction from a 7-item questionnaire. Safety assessments included adverse events (AEs) and laboratory evaluations.

78 participants were randomized, 48 were 9-12 years, 30 were 13-16 years. For the primary efficacy endpoint in 9-12 years, 50.0%, 87.5%, and 81.3% were responders for SPMC ½ dose × 2, SPMC 1 dose × 2, and PEG groups, respectively. Responder rates for 13-16 years were 81.3% for SPMC 1 dose × 2 and 85.7% for PEG. Overall, 43.8% of participants receiving SPMC 1 dose × 2 reported it was ‘very easy’ or ‘easy’ to drink, compared with 20.0% receiving PEG. Treatment-emergent AEs were reported by 45.5% of participants receiving SPMC 1 dose × 2 and 63.0% receiving PEG.

SPMC was an efficacious and safe for bowel preparation in children 9-16 years, with comparable efficacy to PEG. Tolerability for SPMC was higher compared to PEG.

Core Tip: Bowel preparation selection in children should prioritize safety and tolerability, with efficacy an additional important consideration. Currently, there are no universally preferred bowel preparation regimens for children, and standardized protocols are few. Sodium picosulfate, magnesium oxide, and citric acid (SPMC) low volume bowel preparation had higher tolerability in children 9-16 years compared to polyethylene glycol (PEG)-based preparations, potentially due to a lower volume of bowel preparation to ingest. SPMC bowel preparation efficacy and safety were comparable to PEG.

- Citation: Cuffari C, Ciciora SL, Ando M, Boules M, Croffie JM. Pediatric bowel preparation: Sodium picosulfate, magnesium oxide, citric acid vs polyethylene glycol, a randomized trial. World J Gastroenterol 2020; 26(40): 6260-6269

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v26/i40/6260.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v26.i40.6260

Colonoscopy in the pediatric population is commonly used to evaluate gastrointestinal (GI) concerns and remains essential to diagnosing certain GI diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)[1,2]. Several factors play a role in an optimal colonoscopy, including but not limited to effective bowel preparation for complete visualization of the colonic mucosa[3]. Bowel preparation selection and administration in children can be challenging for a variety of reasons, such as a large volume of preparation to ingest, low tolerability of the preparation, or bothersome side effects[2]. The priority for pediatric bowel preparation should be safety and tolerability of the agent, with efficacy being an important consideration as well[2].

Existing clinical practice position on bowel preparation in children from the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition suggests several single-agent best practice regimens for pediatric bowel preparation, including 1-d polyethylene glycol (PEG 3350); 2-d PEG 3350; nasogastric PEG-electrolyte; nasogastric sulfate-free PEG-electrolyte; and magnesium citrate + bisacodyl[4]. However, there is no preferred option, and some preparations are not approved by the FDA for use in children. Additionally, standardized protocols for bowel preparation are lacking, with significant variability in protocols between medical centers and individual practitioners, likely due to the lack of national standards for pediatric bowel preparations for colonoscopy[1,2,4].

Sodium picosulfate, magnesium oxide, and citric acid (SPMC) is a low-volume bowel preparation approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for cleansing of the colon prior to colonoscopy in adults and pediatric patients ages 9 years and older[5]. The objective of this study was to describe the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of SPMC bowel preparation in children. Oral PEG-based bowel preparation solution, per local standard of care, was included as a concurrent reference group.

This was a phase 3, randomized, assessor-blinded, multicenter, dose-ranging study of low-volume SPMC (Ferring Pharmaceuticals Inc., Parsippany, NJ, United States) (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01928862). The study was conducted at 9 sites in the United States, in accordance with the principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki and in compliance with ICH-GCP standards. The study protocol was approved by Institutional Review Boards for each study site (Supplementary Table 1).

Eligible participants were males and females, aged 9 to 16 years, who were undergoing an elective colonoscopy. Females of childbearing potential must have had a negative pregnancy test at screening and randomization. Eligible participants must have had at least 3 spontaneous bowel movements per week for 1 mo prior to colonoscopy, and have been willing, able, and competent to complete the procedure and comply with instructions. Written informed consent (and assent, if applicable) was obtained at screening.

Exclusion criteria included acute surgical abdominal conditions (e.g., acute GI obstruction or perforation); hospitalization for IBD; any prior colorectal surgery (not including appendectomy, hemorrhoid surgery, or prior endoscopic surgery); colon disease (history of colonic cancer, toxic megacolon, toxic colitis, idiopathicpseudo-obstruction, hypomotility syndrome, colon resection); ascites; GI disorder (active ulcer, outlet obstruction, retention, gastroparesis, ileus); upper GI surgery; significant cardiovascular disease; or a history of renal insufficiency with current serum creatinine or potassium levels outside of normal limits.

Use of certain medications was prohibited during the study: Lithium, laxatives (suspended 24 h prior to colonoscopy; not including laxatives as institutional standard of care for colonoscopy bowel preparation), constipating drugs (suspended 2 d prior), antidiarrheals (suspended 72 h prior), and oral iron preparations (suspended 1 wk prior).

Participants were allocated to treatments according to computer-generated randomization codes that were generated by an independent statistician for all study sites. Participants 9-12 years old were randomized 1:1:1 to SPMC ½ dose × 2, SPMC 1 dose × 2, or PEG. Participants 13-16 years old were randomized 1:1 to SPMC 1 dose × 2 or PEG. Randomization numbers were allocated sequentially to participants at each study site, by the order of enrollment.

An unblinded study coordinator enrolled participants electronically, distributed the study drug, and instructed the participant and caregiver(s) about proper use of the study drug. The endoscopist, who performed the colonoscopy and assessed bowel preparation efficacy, and any assistant(s), were blinded to the participant’s treatment group.

Participants and caregivers were instructed to prepare SPMC according to the package insert instructions, as described previously in the SEE CLEAR studies[6,7]. The preferred method was as a split dose, with the first dose administered the evening before (between 5:00p and 9:00p) and second dose administered the morning of colonoscopy (between 5 h and 9 h before the colonoscopy). The alternative dosing method was day-before dosing, with the first dose administered the day before the colonoscopy during the afternoon or early evening, and the second dose administered 6 h later and before midnight. Oral PEG-based bowel preparation solutions were administered per local protocol/standard of care at each study site. The exact preparation administered was recorded by the unblinded study coordinator.

The primary efficacy endpoint was overall quality of colon cleansing by the modified Aronchick Scale (AS) prior to irrigation of the colon (Supplementary Table 2)[8]. The secondary efficacy endpoint was the participant’s tolerability and satisfaction, as measured by a 7-item questionnaire (a version of the Mayo Clinic Bowel Prep Tolerability Questionnaire[9] that was modified for pediatric use; Supplementary Table 3).

Safety assessments included adverse events (AEs), laboratory evaluations, and physical examination. Blood draws for laboratory evaluations were obtained at Screening (within 21 d before colonoscopy), on Day 0 (colonoscopy), and at Day 5 (follow-up). AEs were classified according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) version 20.1.

A total of at least 45 participants were to be exposed to SPMC. In studies of SPMC for bowel preparation in adults, 81.7% to 87.7% had a successful colon cleansing[6,7,10]. The planned sample size would have provided an exact 95% confidence interval (CI) of 65% to 90% if 80% of the participants receiving SPMC were deemed to have successful colon cleansing.

The efficacy analyses were conducted on the intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis set, which included all participants who were randomized. All summaries for the ITT analysis set were made per the randomized treatment group. The primary efficacy endpoint was also summarized on the per-protocol (PP) analysis set by excluding participants who had major protocol deviations. Safety assessments were conducted on the safety analysis set, which included all participants who consumed at least 1 dose of study drug. All summaries for the safety analysis set were made according to actual treatment received.

The primary efficacy outcome (‘responders’) by AS was the proportion of participants receiving an ‘excellent’ or ‘good’ rating. The proportion of responders was summarized by treatment group within each age group, with a conventional two-sided 95%CI as well as a 90%CI. Considering the small sample size, the 90% CI was intended as the more appropriate estimate to present, but the 95%CI was also calculated as it is more widely used. For the secondary efficacy endpoint, participants were considered to have a tolerable experience if they responded ‘never’ or ‘rarely’ to the relevant questions; likewise, they had a satisfactory experience if they responded ‘very easy/well’ or ‘easy/well’ on the relevant questions (Supplementary Table 3).

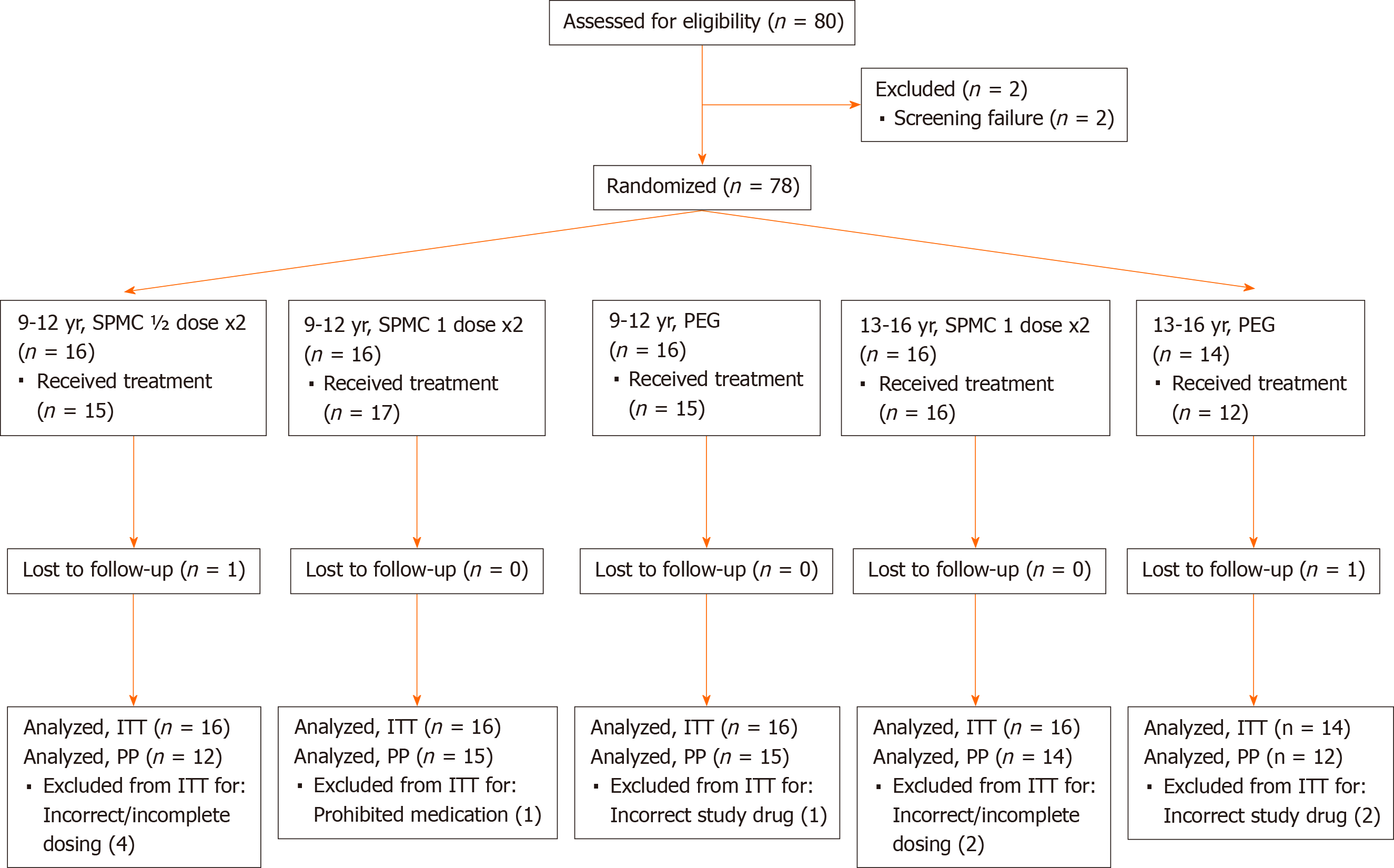

The trial was conducted between June 2014 (first participant enrolled) and March 2017 (last follow-up visit). The trial ended after the expected number of participants had enrolled and completed the trial. A total of 78 participants were randomized, with 48 aged 9-12 years, and 30 aged 13-16 years (Figure 1, Table 1). Of the 48 participants receiving SPMC (safety population), 46 (95.8%) completed both doses of the bowel preparation. Of the 30 participants randomized to PEG arm, 27 received a PEG-based bowel preparation and the remaining 3 received a non-PEG-based preparation (magnesium citrate). All 30 participants randomized to the PEG arm were included in the efficacy analysis set, however only the 27 patients actually ingesting PEG were included in the safety analysis set.

| 9-12 yr old | 13-16 yr old | All SPMC 1 dose × 2 | All PEG | ||||

| n (%) | SPMC ½ dose × 2 | SPMC 1 dose × 2 | PEG | SPMC 1 dose × 2 | PEG | ||

| Age (yr), mean (SD) | 10.8 (1.0) | 10.5 (1.2) | 10.4 (1.2) | 15.0 (1.0) | 14.9 (0.9) | 12.8 (2.5) | 12.5 (2.5) |

| Female, n (%) | 11 (68.8) | 12 (75.0) | 8 (50.0) | 11 (68.8) | 11 (78.6) | 23 (71.9) | 19 (63.3) |

| White race, n (%) | 15 (93.8) | 16 (100) | 11 (68.8) | 15 (93.8) | 14 (100) | 31 (96.9) | 25 (83.3) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 19.0 (4.8) | 20.4 (5.3) | 19.4 (5.2) | 24.9 (7.0) | 23.1 (6.5) | 22.6 (6.5) | 21.1 (6.0) |

A medical history of diarrhea was reported by 27% (13/48) and 27% (8/30) of participants receiving SPMC (any dose) and PEG, respectively; likewise, constipation was reported by 19% (9/48) and 30% (9/30) of participants. In the SPMC treatment arms, split dosing was used for 13/48 (27.1%) participants, and day-before dosing for 35/48 (72.9%). Data on the PEG dosing regimen was available for 22/27 participants, all of whom used a day-before regimen.

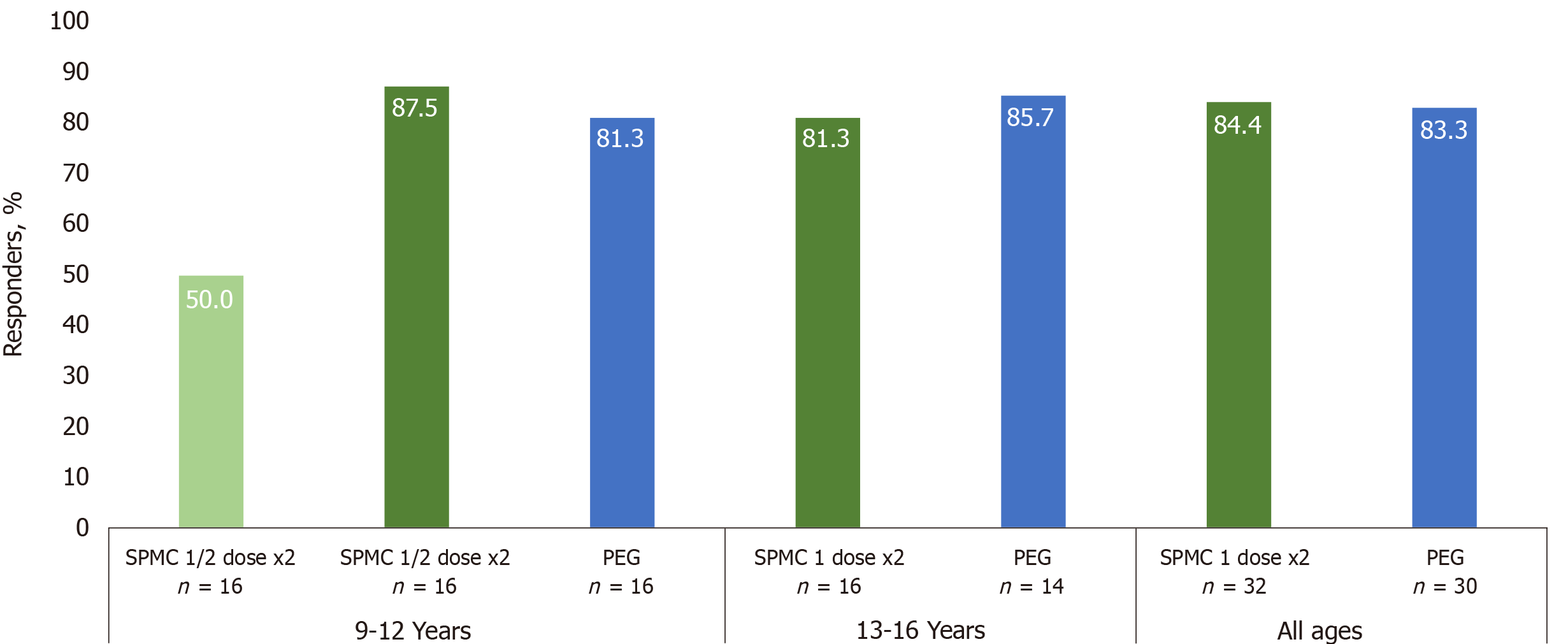

For the primary efficacy endpoint, responders by AS, SPMC 1 dose × 2 showed consistent efficacy compared to PEG in both age groups (Figure 2). In the 9-12 years group, 87.5% (90%CI: 65.6%, 97.7%) were responders for SPMC 1 dose × 2 treatment arm, and 81.3% (90%CI: 58.3%, 94.7%) were responders for PEG treatment arm. In the 13-16 years group, 81.3% (90%CI: 58.3%, 94.7%) were responders for SPMC 1 dose × 2 treatment arm, and 85.7% (90%CI: 61.5%, 97.4%) were responders for PEG treatment arm. In the SPMC ½ dose × 2 arm (9-12 years only), 50.0% (90%CI: 27.9%, 72.1%) of participants were responders.

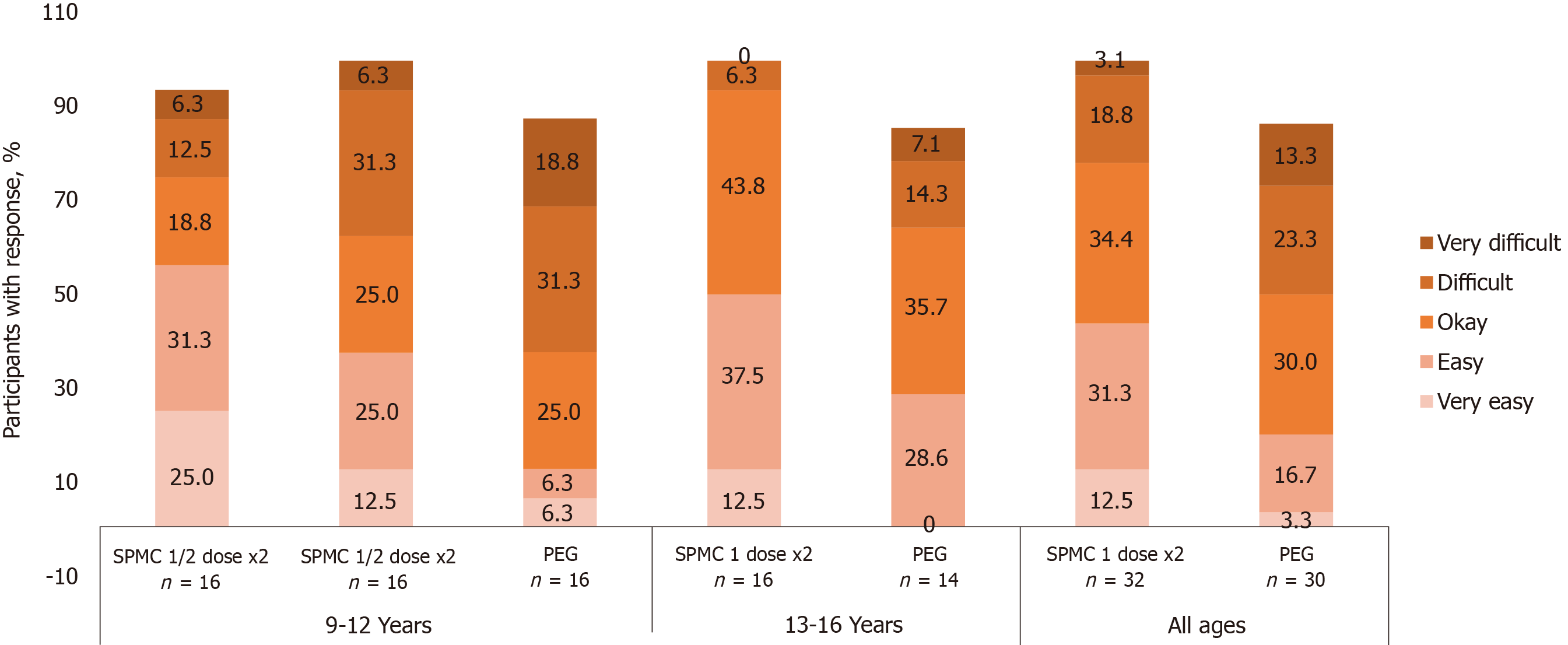

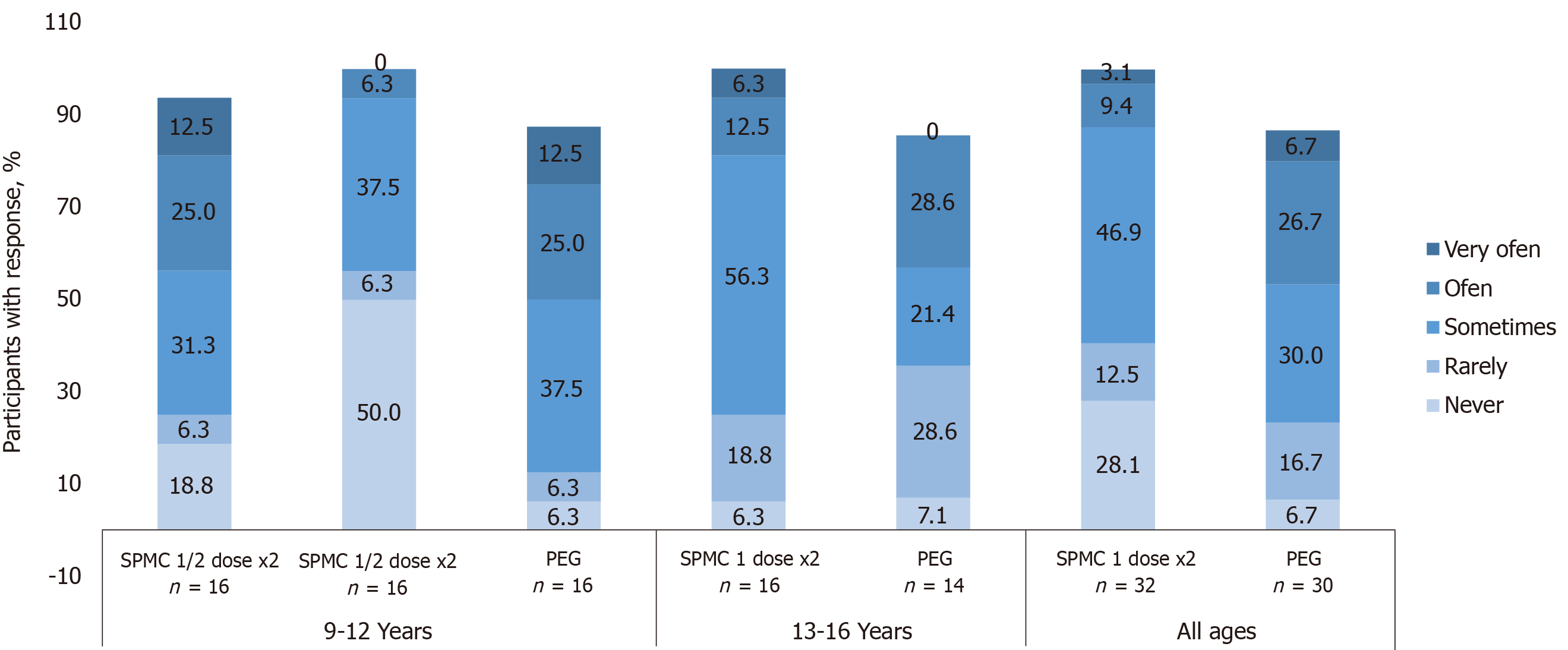

From the tolerability and satisfaction questionnaire, in both age groups, a greater number of participants receiving SPMC 1 dose × 2 found it ‘very easy’ or ‘easy’ to ingest than those receiving PEG (Figure 3). Likewise, fewer patients receiving SPMC 1 dose × 2 reported abdominal discomfort happened ‘often’ or ‘very often’ compared to those receiving PEG (Figure 4). Feeling nausea ‘often’ or ‘very often’ during the bowel preparation was reported by 40% (12/30) of participants receiving PEG and by 18.6% (6/32) of participants receiving SPMC 1 dose × 2. A greater percentage of participants who received SPMC were ‘never’ or ‘rarely’ bothered about going to the bathroom compared to those receiving PEG (43.8% vs 13.3%). No relevant differences were reported between PEG and SPMC for taste or how often the participant woke during the night.

Treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) were reported by 45.5% (15/33) of participants who received SPMC 1 dose x2 and 63.0% (17/27) of participants who received PEG (Table 2). One participant receiving SPMC 1 dose × 2 reported severe AEs: Abdominal pain (considered related to study drug, participant did not receive second dose, AE resolved), GI inflammation (Crohn’s disease, unrelated to study drug), and intestinal ulcer (unrelated to study drug).

| 9-12 yr old | 13-16 yr old | All SPMC 1 dose × 2 (n = 33) | All PEG | ||||

| n (%) | SPMC ½ dose × 2 (n = 15) | SPMC 1 dose × 2 (n = 17) | PEG | SPMC 1 dose × 2 (n = 16) | PEG | ||

| Any TEAE | 8 (53.3) | 5 (29.4) | 6 (40.0) | 10 (62.5) | 11 (91.7) | 15 (45.5) | 17 (63.0) |

| Deaths | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Serious TEAE | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| TEAE leading to study discontinuation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Severe AE | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (6.3) | 0 | 1 (3.0) | 0 |

| ADR | 1 (6.7) | 0 | 1 (6.7) | 4 (25.0) | 4 (33.3) | 4 (12.1) | 5 (18.5) |

| Nausea | 1 (6.7) | 0 | 1 (6.7) | 1 (6.3) | 3 (25.0) | 1 (3.0) | 4 (14.8) |

| Vomiting | 1 (6.7) | 0 | 0 | 2 (12.5) | 1 (8.3) | 2 (6.1) | 1 (3.7) |

| Abdominal pain | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (6.3) | 0 | 1 (3.0) | 0 |

| Retching | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (6.3) | 0 | 1 (3.0) | 0 |

| Migraine | 1 (6.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hyperhidrosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (6.3) | 0 | 1 (3.0) | 0 |

| Serious ADR | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Treatment-emergent adverse drug reactions (ADRs) were reported by 12.1% (4/33) of participants for SPMC and 18.5% (5/27) for PEG (Table 2). The most commonly reported ADRs were vomiting (6.1% vs 3.7%) and nausea (3.0% vs 14.8%) for SPMC 1 dose × 2 and PEG groups, respectively.

Laboratory values and vital signs showed no meaningful changes associated with study drug administration. Three participants had abnormally low blood glucose (40-47 mg/dL) (2 in the SPMC 1 dose × 2 cohort; 1 in the PEG arm), which occurred on Day 0 for 1 participant receiving SPMC, and on Day 5 for 1 participant receiving SPMC and 1 receiving PEG; participants did not experience clinically-meaningful symptoms related to the hypoglycemia. Participants receiving SPMC 1 dose × 2 showed small and transient increases in magnesium, from a mean (SD) of 0.89 (0.07) mmol/L at baseline to 1.04 (0.14) mmol/L on Day 0, which returned to 0.94 (0.22) mmol/L on Day 5 (follow-up), with no clinically-meaningful symptoms.

SPMC was safe for bowel cleansing in children, with no reports of serious adverse events. Numerically, SPMC was associated with fewer reports of any treatment-emergent adverse event or adverse drug reaction compared to PEG, including a much lower rate of nausea (3.0% vs 14.8%). Glucose and magnesium imbalances that were measured by laboratory assessments were transient, not clinically significant, and similar to those reported for adults receiving SPMC[5]. The finding of transient magnesium imbalance is not surprising given the presence of magnesium oxide in SPMC.

The tolerability for SPMC was higher compared to PEG, with more than double the proportion rating the bowel preparation as ‘very easy’ or ‘easy’ to ingest. In children, the tolerability and safety of bowel preparation carries equal or greater importance to the efficacy. Administering bowel preparations in children, and achieving compliance with administration, remains challenging. The tolerability of the pediatric standard of care for bowel preparation, PEG, is recognized to be less than optimal[5]. Here, SPMC was more tolerable than the standard of care for bowel preparation, and almost all participants receiving SPMC ingested both doses. One possible factor for the favorable tolerability for SPMC is the volume of bowel preparation ingested (active medication 5.4 oz per 1 dose, or 10.8 oz in total for both doses) relative to a typical volume of PEG for bowel preparation (approximately 64-72 oz for children 9-16 years)[4,11]. Participants receiving SPMC ingested additional liquid of their choice to complete the bowel preparation. The actual volume of PEG ingested by participants in this study was not available, which may be variable in the pediatric population. A randomized trial showed that split-dosing of PEG (vs single dosing) led to a more tolerable bowel preparation experience in children[11].

SPMC was efficacious in children 9 to 16 years old, and comparable to the bowel cleansing efficacy of PEG. SPMC 1 dose × 2 displayed high and consistent efficacy across the two age groups, 9-12 years and 13-16 years. SPMC demonstrated a dose-response relationship in the 9-12 years group, with SPMC ½ dose × 2 arm showing a 50% responder rate, while the SPMC 1 dose × 2 arm had an 87.5% responder rate.

This study adds new data to the sparse literature on bowel preparation in children. Very few studies have evaluated the use of SPMC for bowel preparation in the pediatric population, and not all commonly used bowel preparations are FDA approved for use in children[12-15]. The results of this study are consistent with earlier studies of sodium picosulfate/SPMC in children, which demonstrated good efficacy of colon cleansing and improved tolerability compared to bisacodyl or PEG[12-15,16].

Existing guidelines suggest PEG as the standard of care for bowel preparation in children, with the caveat that many of the studies used to support the suggestion implemented a 4-d bowel preparation regimen, and some added a stimulant to the preparation (e.g., bisacodyl)[17,18]. Realistically, feasibility of a 4-d preparation regimen becomes more cumbersome and inconvenient, with the potential to reduce cleansing efficacy as patients are more likely to be noncompliant for a 4-d regimen, when compared to a low-volume 2-d regimen[2,4]. Here, the SPMC protocol was a 2-d bowel preparation without the addition of a stimulant, which has been shown to improve patient satisfaction with other preparations. Guidelines also suggest that pediatric bowel preparation regimens should prioritize safety and tolerability and the SPMC protocol seems to achieve such[2].

As the tolerability was higher and the efficacy and safety were consistent with the standard of care for pediatric bowel preparation, SPMC 1 dose × 2 should be considered as a more feasible and easier-to-consume option compared to PEG for all bowel preparations in children 9 to 16 years old.

Quality bowel preparation is a critical factor for colonoscopy success. Bowel preparation selection in children should prioritize safety and tolerability, with efficacy an additional important consideration.

Currently, there are no universally preferred bowel preparation regimens for children, and standardized protocols are few.

The objective of this study was to describe the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of sodium picosulfate, magnesium oxide, and citric acid (SPMC) low volume bowel preparation in pediatric patients 9 to 16 years old.

A phase 3, randomized, assessor-blinded, multicenter, dose-ranging study of low volume SPMC bowel preparation or polyethylene glycol (PEG) bowel preparation. Male and female children, 9 to 16 years, who were undergoing elective colonoscopy were eligible for the study. Participants 9-12 years old were randomized 1:1:1 to SPMC ½ dose × 2, SPMC 1 dose × 2, or PEG. Participants 13-16 years old were randomized 1:1 to SPMC 1 dose × 2 or PEG. Efficacy of overall colon cleansing was assessed by the modified Aronchick scale (AS), tolerability was assessed by a 7-item questionnaire, and safety was assessed by reports of adverse events (AEs) and laboratory evaluations.

A total of 78 participants were randomized, with 48 aged 9-12 years, and 30 aged 13-16 years. In the 9-12 years group, 87.5% (90%CI: 65.6%, 97.7%) were responders for SPMC 1 dose × 2 treatment arm, and 81.3% (90%CI: 58.3%, 94.7%) were responders for PEG treatment arm. In the 13-16 yr group, 81.3% (90% CI: 58.3%, 94.7%) were responders for SPMC 1 dose × 2 treatment arm, and 85.7% (90%CI: 61.5%, 97.4%) were responders for PEG treatment arm. In the SPMC ½ dose × 2 arm (9-12 years only), 50.0% (90%CI: 27.9%, 72.1%) of participants were responders. In both age groups, a greater number of participants receiving SPMC 1 dose × 2 found it ‘very easy’ or ‘easy’ to ingest than those receiving PEG. Treatment-emergent AEs were reported by 45.5% of participants receiving SPMC 1 dose x2 and 63.0% receiving PEG.

Sodium picosulfate, magnesium oxide, and citric acid low volume bowel preparation had higher tolerability in children 9-16 years compared to polyethylene glycol-based preparations, potentially due to a lower volume of bowel preparation to ingest. SPMC bowel preparation efficacy and safety were comparable to PEG.

As the tolerability was higher and the efficacy and safety were consistent with the standard of care for pediatric bowel preparation, SPMC 1 dose x2 should be considered as a more feasible and easier-to-consume option compared to PEG for all bowel preparations in children 9 to 16 years old.

The authors would like to thank the investigators, study staff, and participants who were involved in the trial.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership(s) in Professional Societies: American College of Gastroenterology; American Gastroenterological Association; Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons (Canada).

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Hu LH S-Editor: Wang DM L-Editor: A P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Hunter A, Mamula P. Bowel preparation for pediatric colonoscopy procedures. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51:254-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Lightdale JR; Acosta R; Shergill AK; Chandrasekhara V; Chathadi K; Early D; Evans JA; Fanelli RD; Fisher DA; Fonkalsrud L; Hwang JH; Kashab M; Muthusamy VR; Pasha S; Saltzman JR; Cash BD. Modifications in endoscopic practice for pediatric patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:699-710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Saltzman JR, Cash BD, Pasha SF, Early DS, Muthusamy VR, Khashab MA, Chathadi KV, Fanelli RD, Chandrasekhara V, Lightdale JR, Fonkalsrud L, Shergill AK, Hwang JH, Decker GA, Jue TL, Sharaf R, Fisher DA, Evans JA, Foley K, Shaukat A, Eloubeidi MA, Faulx AL, Wang A, Acosta RD. Bowel preparation before colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:781-794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in RCA: 305] [Article Influence: 30.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Pall H, Zacur GM, Kramer RE, Lirio RA, Manfredi M, Shah M, Stephen TC, Tucker N, Gibbons TE, Sahn B, McOmber M, Friedlander J, Quiros JA, Fishman DS, Mamula P. Bowel preparation for pediatric colonoscopy: report of the NASPGHAN endoscopy and procedures committee. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;59:409-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | CLENPIQ. [package insert]. 2019: Parsippany, NJ: Ferring Pharmaceuticals Inc. |

| 6. | Katz PO, Rex DK, Epstein M, Grandhi NK, Vanner S, Hookey LC, Alderfer V, Joseph RE. A dual-action, low-volume bowel cleanser administered the day before colonoscopy: results from the SEE CLEAR II study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:401-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rex DK, Katz PO, Bertiger G, Vanner S, Hookey LC, Alderfer V, Joseph RE. Split-dose administration of a dual-action, low-volume bowel cleanser for colonoscopy: the SEE CLEAR I study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:132-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Aronchick CA, Lipshutz WH, Wright SH, Dufrayne F, Bergman G. A novel tableted purgative for colonoscopic preparation: efficacy and safety comparisons with Colyte and Fleet Phospho-Soda. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:346-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 283] [Cited by in RCA: 318] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Patel M, Staggs E, Thomas CS, Lukens F, Wallace M, Almansa C. Development and validation of the Mayo Clinic Bowel Prep Tolerability Questionnaire. Dig Liver Dis. 2014;46:808-812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hookey L, Bertiger G, Lee Johnson K 2nd, Ayala J, Seifu Y, Brogadir SP. Efficacy and safety of a ready-to-drink bowel preparation for colonoscopy: a randomized, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2019;12:1756284819851510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tripathi PR, Poddar U, Yachha SK, Sarma MS, Srivastava A. Efficacy of Single- Versus Split-dose Polyethylene Glycol for Colonic Preparation in Children: A Randomized Control Study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2020;70:e1-e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Jimenez-Rivera C, Haas D, Boland M, Barkey JL, Mack DR. Comparison of two common outpatient preparations for colonoscopy in children and youth. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2009;2009:518932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Turner D, Benchimol EI, Dunn H, Griffiths AM, Frost K, Scaini V, Avolio J, Ling SC. Pico-Salax vs polyethylene glycol for bowel cleanout before colonoscopy in children: a randomized controlled trial. Endoscopy. 2009;41:1038-1045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Vejzovic V, Wennick A, Idvall E, Agardh D, Bramhagen AC. Polyethylene Glycol- or Sodium Picosulphate-Based Laxatives Before Colonoscopy in Children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;62:414-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Pinfield A, Stringer MD. Randomised trial of two pharmacological methods of bowel preparation for day case colonoscopy. Arch Dis Child. 1999;80:181-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Di Nardo G, Aloi M, Cucchiara S, Spada C, Hassan C, Civitelli F, Nuti F, Ziparo C, Pession A, Lima M, La Torre G, Oliva S. Bowel preparations for colonoscopy: an RCT. Pediatrics. 2014;134:249-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Pashankar DS, Uc A, Bishop WP. Polyethylene glycol 3350 without electrolytes: a new safe, effective, and palatable bowel preparation for colonoscopy in children. J Pediatr. 2004;144:358-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Safder S, Demintieva Y, Rewalt M, Elitsur Y. Stool consistency and stool frequency are excellent clinical markers for adequate colon preparation after polyethylene glycol 3350 cleansing protocol: a prospective clinical study in children. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:1131-1135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |