Published online Oct 28, 2020. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i40.6241

Peer-review started: May 16, 2020

First decision: May 29, 2020

Revised: June 9, 2020

Accepted: October 1, 2020

Article in press: October 1, 2020

Published online: October 28, 2020

Processing time: 165 Days and 2.3 Hours

Mirizzi syndrome (MS) is defined as an extrinsic compression of the extrahepatic biliary system by an impacted stone in the gallbladder or the cystic duct leading to obstructive jaundice. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) could serve diagnostic and therapeutic purposes in patients with MS in addition to revealing the relationships between the cystic duct, the gallbladder, and the common bile duct (CBD). Cholecystectomy is a challenging procedure for a laparoscopic surgeon in patients with MS, and the presence of a cholecystocholedochal fistula renders preoperative diagnosis important during ERCP.

To evaluate cholecystocholedochal fistulas in patients with MS during ERCP before cholecystectomy.

From 2004 to 2018, all patients diagnosed with MS during ERCP were enrolled in this study. Patients with associated malignancy or those who had already undergone cholecystectomy before ERCP were excluded. In total, 117 patients with MS diagnosed by ERCP were enrolled in this study. Among them, 21 patients with MS had cholecystocholedochal fistulas. MS was further confirmed during cholecystectomy to check if cholecystocholedochal fistulas were present. The clinical data, cholangiography, and endoscopic findings during ERCP were recorded and analyzed.

Gallbladder opacification on cholangiography is more frequent in patients with MS complicated by cholecystocholedochal fistulas (P < 0.001). Pus in the CBD and stricture length of the CBD longer than 2 cm were two additional independent factors associated with MS, as demonstrated by multivariate analysis (odds ratio 5.82, P = 0.002; 0.12, P = 0.008, respectively).

Gall bladder opacification is commonly seen in patients with MS with cholecystocholedochal fistulas during pre-operative ERCP. Additional findings such as pus in the CBD and stricture length of the CBD longer than 2 cm may aid the diagnosis of MS with cholecystocholedochal fistulas.

Core Tip: The diagnosis of Mirizzi syndrome (MS) and the presence or absence of a cholecystocholedochal fistula is important for surgical planning before cholecystectomy. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography could serve diagnostic and therapeutic purposes in patients with MS and also help detect cholecystocholedochal fistulas before operation. Our study revealed that gall bladder opacification is more frequent in patients with cholecystocholedochal fistula. Pus in the common bile duct is predictive factor for the diagnosis of MS with cholecystocholedochal fistulas, and stricture length of the common bile duct longer than 2 cm is the protective factor for cholecystocholedochal fistulas in patients with MS.

- Citation: Wu CH, Liu NJ, Yeh CN, Wang SY, Jan YY. Predicting cholecystocholedochal fistulas in patients with Mirizzi syndrome undergoing endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. World J Gastroenterol 2020; 26(40): 6241-6249

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v26/i40/6241.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v26.i40.6241

Mirizzi syndrome (MS) is defined as an extrinsic compression of the extrahepatic biliary system by an impacted stone in the gallbladder or the cystic duct, leading to obstructive jaundice. Cholecystectomy in a patient with MS and the presence of a cholecystocholedochal fistula is a complex and challenging procedure for a laparoscopic surgeon, making preoperative diagnosis important during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) examination.

Pablo Mirizzi first described MS in 1948[1]. McSherry et al[2] classified this syndrome into two distinct types: Extrinsic compression of the common hepatic duct by the gallbladder and erosion of the gallstone from the gallbladder or the cystic duct into the common hepatic duct resulting in a cholecystocholedochal fistula. In 1989, Csendes et al[3] further proposed a new classification of patients with MS that also divided patients into two categories: External compression (Type 1) and fistulas from the gallbladder to the common bile or hepatic duct (Types 2-4). Laparoscopic surgery can be used to treat MS of the extrinsic compression type[4]. However, operating on patients with MS with cholecystocholedochal fistulas is still a challenge[5-8]. In such situations, the preoperative diagnosis of the cholecystocholedochal fistula is crucial. In previous studies, cholecystocholedochal fistulas were detected by intraoperative cholangiography during cholecystectomy. Recently, ERCP has not only played a therapeutic-operative role but has also provided diagnostic perspectives before operation. The incidence of MS is estimated to be 1.07% in patients who underwent ERCP[9]. A typical cholangiography of MS consists of dilated intrahepatic ducts and pronounced narrowing of the common hepatic duct due to compression near the cystic duct or the gallbladder. ERCP may be useful in patients with MS in the retrieval of the common bile duct (CBD) stones after a sphincterotomy and placement of stents in the bile duct for drainage. This study is a retrospective analysis that aimed to investigate predictive factors for patients with MS with cholecystocholedochal fistulas during ERCP before laparoscopic surgery.

We conducted a retrospective study involving patients diagnosed with MS during preoperative ERCP examination. All patients underwent cholecystectomy at the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Linkou Branch, which is a tertiary care academic hospital. Data were collected from an extensive retrospective chart review.

From 2004 to 2018, all patients diagnosed with MS during ERCP were enrolled in this study. The diagnosis of MS with or without a cholecystocholedochal fistula was confirmed by intraoperative findings. Patients with associated malignancy or those who had already undergone cholecystectomy before ERCP were excluded from this study. Demographic data, clinical presentation information, and blood test results were recorded. The diagnosis of cholangitis was based on Tokyo Guidelines 2018 for cholangitis, which included acute inflammation, cholestasis, and imaging depicting bile duct dilation[10]. Endoscopic and cholangiographic findings during ERCP were also recorded and analyzed. Pus detected from the bile duct orifice at the papilla of Vater were defined as pus in the CBD. Contrast medium that filled the cystic duct or the gall bladder was defined as cystic duct or gall bladder opacification

The study was approved by the Chang Gung Medical Foundation Institutional Review Board (IRB number: 201801210B0). Data acquisition and analysis were carried out in accordance with guidelines and regulations. Due to the retrospective design of the study, consent was waived by the ethics committee for the entire study.

Continuous variables are presented as means ± SD, and categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages. The differences between patients with MS with or without cholecystocholedochal fistulas were compared using Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was employed to determine independent significant factors. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). A two-sided P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 117 patients were suspected of having MS during ERCP; this was confirmed during operation between 2004 and 2018. The incidence of MS was 0.9% of all ERCP procedures (n approximately 13000) performed during the same period. Twenty-one patients with MS had a cholecystocholedochal fistula, and 96 patients with MS suffered only from external compression. The two groups of patients did not differ in age, sex, clinical findings, or laboratory data. The laboratory data included total bilirubin, serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase, glutamic-pyruvic transaminase, alkaline phosphatase, and leukocyte counts (Table 1).

| MS with fistula formation, n = 21 | MS without fistula formation, n = 96 | P value | |

| Age in yr | 56 ± 15 | 57 ± 15 | 0.72 |

| Sex, male/female | 16/5 | 63/33 | 0.45 |

| Clinical symptom, n (%) | |||

| Abdominal pain | 14 (66.67) | 86 (77.08) | 0.40 |

| Jaundice | 15 (71.42) | 81 (79.17) | 0.56 |

| Cholangitis | 10 (47.62) | 54 (56.25) | 0.48 |

| Laboratory findings | |||

| Bilirubin in mg/dL | 7.60 ± 7.81 | 5.87 ± 5.25 | 0.45 |

| ALK-P in U/L | 243.61 ± 162.74 | 205.20 ± 130.85 | 0.46 |

| SGOT in U/L | 136.53 ± 116.85 | 197.09 ± 202.04 | 0.27 |

| SGPT in U/L | 226.69 ± 177.39 | 304.10 ± 290.84 | 0.47 |

| Leukocytes as × 103/L | 11.56 ± 14.02 | 9.56 ± 3.51 | 0.55 |

For pre-operative diagnosis, all patients who underwent ultrasonography initially revealed stones in the gall bladder. Ninety patients further underwent computed tomography, and 85 patients revealed a dilated intrahepatic or extrahepatic bile duct before ERCP. Moreover, 24 patients underwent magnetic resonance cholangio-pancreatography (MRCP), 20 patients showed external compression of the hepatic ducts and were suspected to have MS. Among the 21 patients with MS with cholecystocholedochal fistula, MRCP was performed in four patients, but none of the patients could be diagnosed with cholecystocholedochal fistula on MRCP.

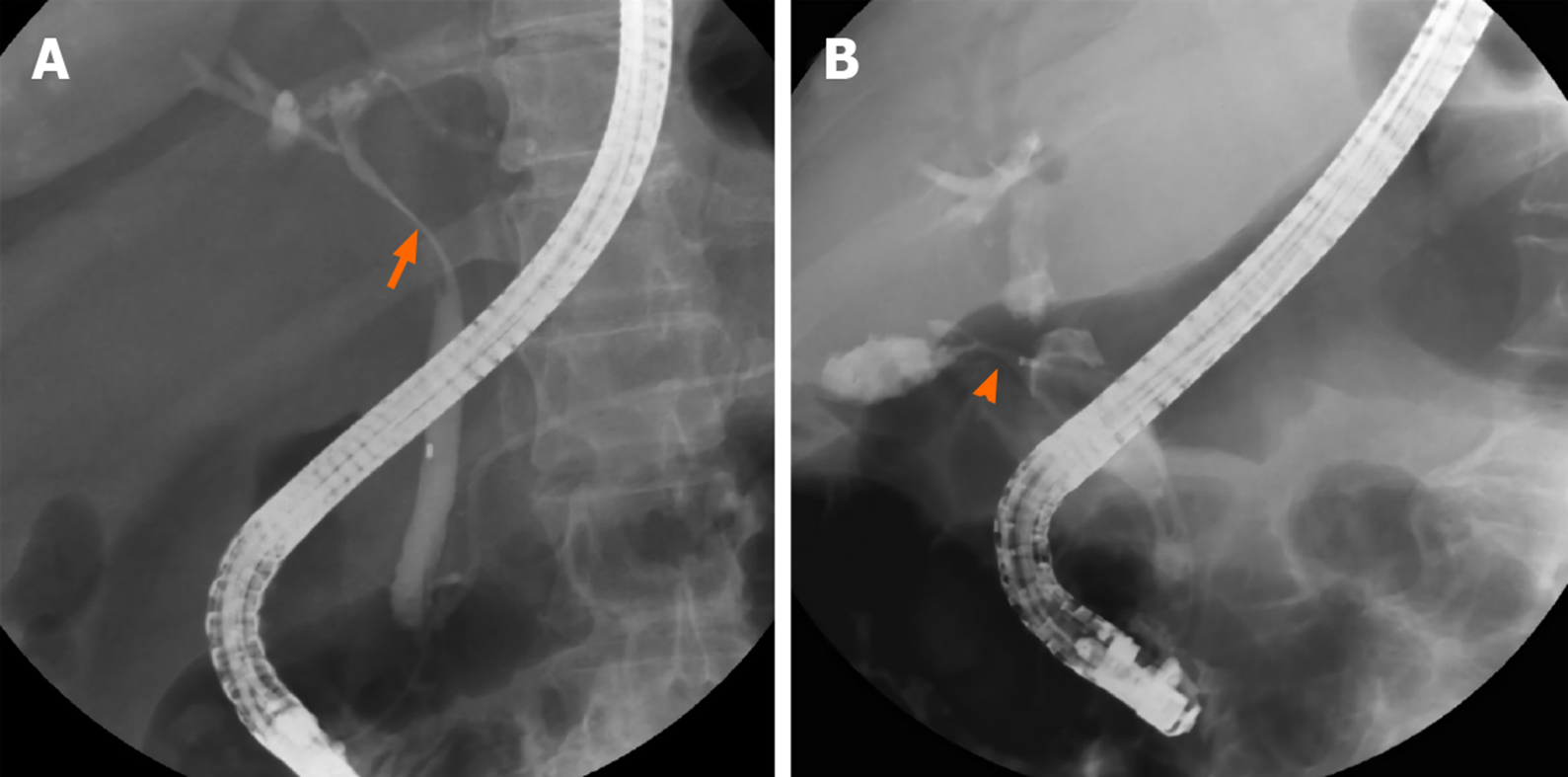

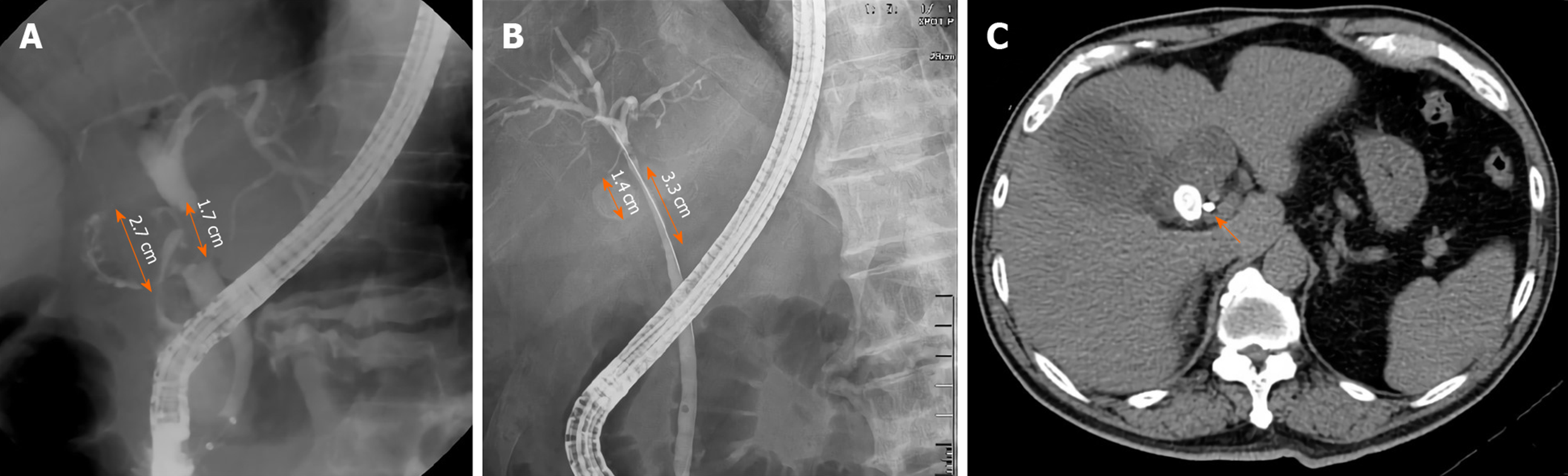

Figure 1 shows the cholangiography during ERCP for patients with MS with and without a cholecystocholedochal fistula (Figure 1). The percentage of cystic duct opacification was similar between the two groups (10/21 patients (47.61%) with a fistula vs 46/96 patients (47.92%) without a fistula; P = 0.81). However, patients with MS and cholecystocholedochal fistula had a significantly higher percentage of gallbladder opacification than those without (76.19% vs 23.96%; P < 0.001).

Other than the original purpose of ERCP, which was to reveal the relationship of the cystic duct, the gall bladder, and the CBD, some additional factors were obtained during the procedure. Stricture length at the CBD longer than 2 cm was more frequent in patients with MS without a cholecystocholedochal fistula than in those with a fistula (42.71% vs 9.52%; P = 0.005). CBD stones are often found during ERCP and are important indications for ERCP. We retrieved as many CBD stones as possible during our routine practice. The incidence of CBD stone retrieval was similar in both groups (2/21 (9.52%) in patients with MS with a cholecystocholedochal fistula, and 28/96 (29.17%) in patients without; P = 0.09). However, both groups of patients had a much lower incidence of CBD stone retrieval compared with the patients in the routine ERCP examination group.

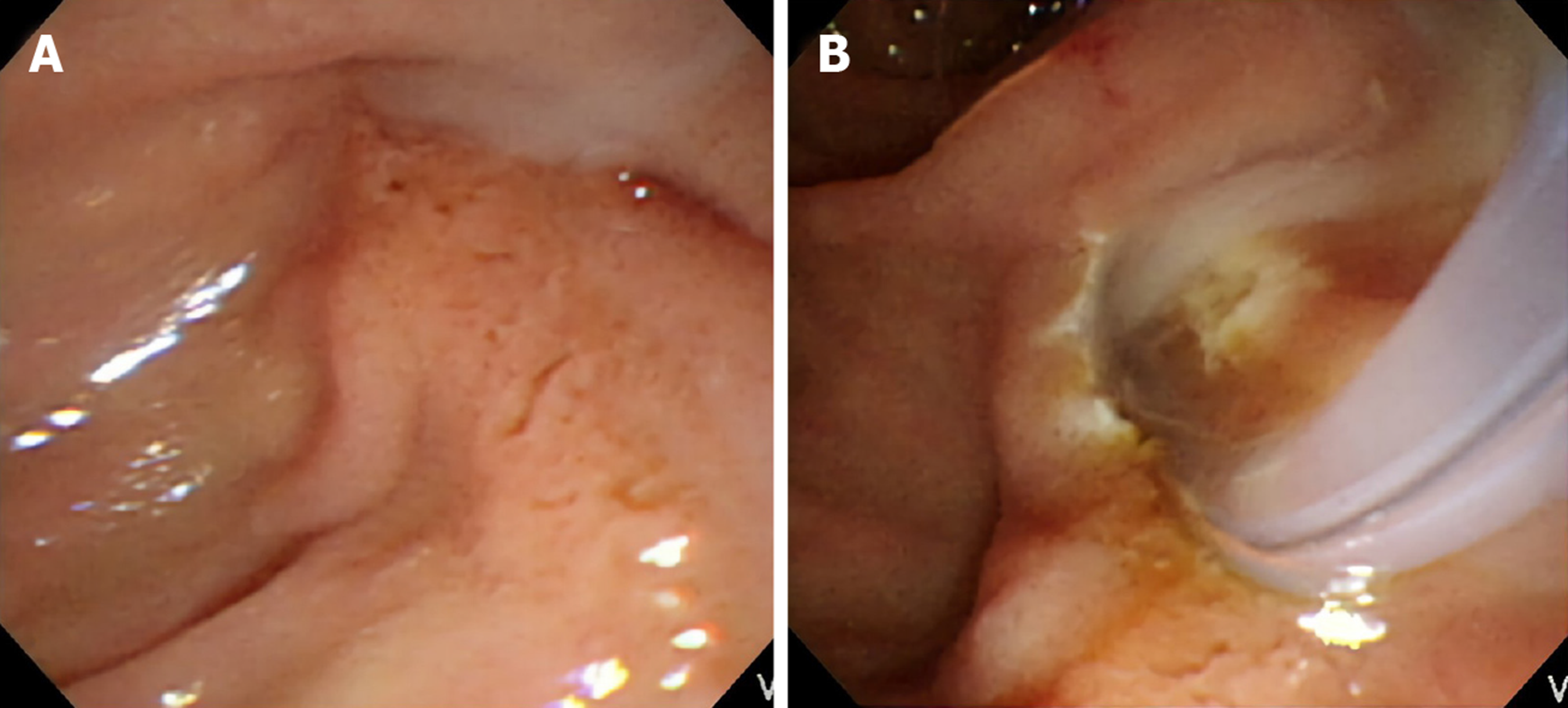

Stress-related peptic ulcers were a common finding with bile duct obstruction, which was previously described in many studies, especially in animal models[11-14]. Six (28.57%) patients had duodenal ulcers found during ERCP in the group affected by MS with a cholecystocholedochal fistula, and 19 (19.79%) patients had duodenal ulcers in the group affected by MS without a cholecystocholedochal fistula. However, the difference between the two groups was not significant (P = 0.39). In contrast, pus formation in the CBD was seen frequently in patients with MS during ERCP (Figure 2). Further, patients with a cholecystocholedochal fistula had a higher percentage of pus in the CBD compared to patients without a cholecystocholedochal fistula (47.62% vs 15.63%; P = 0.003) (Table 2).

| MS with fistula formation, n = 21 | MS without fistula formation, n = 96 | P value | |

| Original findings | |||

| Cystic duct opacification | 10 (47.61) | 46 (47.92) | 0.81 |

| GB opacification | 16 (76.19) | 26 (23.96) | < 0.001 |

| Additional findings | |||

| Stricture length > 2 cm | 2 (9.52) | 41 (42.71) | 0.005 |

| CBD stones retrieved | 2 (9.52) | 28 (29.17) | 0.09 |

| Pus in the CBD | 10 (47.62) | 15 (15.63) | 0.003 |

| Duodenal ulcer | 6 (28.57) | 19 (19.79) | 0.39 |

Logistic regression analysis was used to determine additional factors that could be predictive factors for the presence of a cholecystocholedochal fistula through endoscopic or cholangiography findings during ERCP (Table 3). Significant predictors of a cholecystocholedochal fistula based on univariate analysis were pus in the CBD and stricture length > 2 cm at the CBD. Multivariate analysis with a multiple logistic regression model showed pus in the CBD had greater odds of predicting a cholecystocholedochal fistula in patients with MS (odds ratio (OR) 5.82, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.93-17.58, P = 0.002). Patients with MS with a stricture length longer than 2 cm at the CBD were less likely to have a cholecystocholedochal fistula (OR 0.12, 95%CI: 0.03-0.58, P = 0.008).

| Univariate OR | P value | 95%CI for OR | Multivariate OR | P value | 95%CI for OR | |

| Variate | ||||||

| Stricture length > 2 cm | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.03-0.64 | 0.12 | 0.008 | 0.03-0.58 |

| CBD stones retrieved | 0.26 | 0.08 | 0.06-1.17 | |||

| Pus in the CBD | 4.91 | 0.002 | 1.77-13.59 | 5.82 | 0.002 | 1.93-17.58 |

| Duodenal ulcer | 1.62 | 0.38 | 0.56-4.73 |

All patients received bile duct drainage since they were referred for ERCP due to a clinically suspected bile duct obstruction (18 patients received endoscopic nasobiliary drainage, and 99 patients received endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage with 10 French or 8.5 French plastic stents). Three patients suffered from mild pancreatitis post ERCP and recovered in 1 wk.

In this study, several novel endoscopic findings were identified to predict cases of MS complicated with cholecystocholedochal fistulas. MS is a rare complication of gallstone disease, with a reported incidence ranging from 0.06% to 5.7% in patients undergoing cholecystectomy[15,16]. In 1942, Puestow reported a series of 16 patients who had a spontaneous internal biliary fistula between the gallbladder and CBD[17]. McSherry et al[2] and Csendes et al[3] further described patients with MS and a cholecysto-choledochal fistula. MS without a cholecystocholedochal fistula can initially be treated laparoscopically[18-21]. However, the surgical treatment of MS with a cholecysto-choledochal fistula is more difficult, and laparotomy cholecystectomy was often used. Sometimes a T-tube may be placed in the CBD, away from the fistulous site, to prevent future stricture or worsening of the fistula, or a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy should be performed[3,5-8,22,23]. Hence, predicting a cholecystocholedochal fistula before cholecystectomy could help the surgeon make more precise surgical plans.

Based on the above findings, the preoperative diagnosis of a biliary fistula is crucial. Abdominal ultrasound has a 96% sensitivity for gallstone detection[24]. Computed tomography can demonstrate the level of obstruction and is also able to exclude neoplastic lesions located at the hepatic hilum or the liver in patients with MS[25,26]. However, neither tool is ideal for diagnosing cholecystocholedochal fistulas. MRCP is as good as ERCP in diagnosing and delineating the details of biliary strictures. However, compared with ERCP, MRCP does not offer simultaneous therapeutic stenting[27]. Although intraoperative cholangiography can be performed on patients with MS during cholecystectomy, ERCP provides a cholangiogram and illustrates the relationship between the CBD, the cystic duct, and the gallbladder preoperatively.

First, a higher percentage of opacification of the gallbladder is seen during ERCP examination in patients with MS with a cholecystocholedochal fistula. In most patients with MS, the stones wreck the walls of the bile duct. As time passes, the stone can gradually migrate into the bile duct, causing necrosis of the duct, leading to a cholecystocholedochal fistula[25,28]. The elevated gallbladder pressure due to the cystic duct or the gallbladder neck obstruction in patients without a cholecystocholedochal fistula makes contrast difficult to enhance the gallbladder. The gallbladder pressure is then released after formation of the cholecystocholedochal fistula. Taken together, this could explain the higher percentage of opacification of the gallbladder during ERCP in this study.

Second, a stricture length longer than 2 cm at the CBD is another important endoscopic finding in patients with MS without a fistula. Interestingly, the stone size in patients with MS with a cholecystocholedochal fistula was larger (median 2.25 cm) than in those without a cholecystocholedochal fistula (median 1.5 cm)[29]. Theoretically, the stricture length of the CBD is longer in patients with MS with a cholecystocholedochal fistula. Contrary to our analysis, we hypothesized that the longer stricture of the CBD might be related to the compression of the distended gallbladder or the cystic duct rather than the direct compression by the stone itself. After cholecystocholedochal fistula formation, the gallbladder and cystic duct decompress, and the stricture of the CBD may result from the direct compression by the stone, shortening the stricture length (Figure 3).

ERCP also provides extra information in endoscopic findings not typically seen using intraoperative cholangiography. CBD stone is the most frequent finding during ERCP in patients with gallstones. In our series, we retrieved as many CBD stones as possible but only 10%-30% of patients had CBD stones in each of our groups, which is a much lower rate than in the regular patient population undergoing ERCP[30,31]. In MS, most of the bile duct obstruction is caused by external compression. Even in patients with a cholecystocholedochal fistula, only a small part of the stone eroded into the CBD, making it difficult to retrieve the stone. Previous studies have reported that stones causing MS are not always amenable to removal by ERCP methods[32]. This could explain the low retrieval rate of CBD stones in patients with MS.

The last novel endoscopic finding was that pus in the CBD was more frequently found in patients with MS with cholecystocholedochal fistulas, presenting as an independent predictive factor, as demonstrated by multivariate logistic regression analysis. The incidence of pus in the CBD was up to 50% in patients with MS with a cholecystocholedochal fistula and only 15% in patients with MS without a fistula. Pus in the bile duct, or suppurative cholangitis, caused by calculus obstruction of the CBD and superimposed infection involving the entire biliary tract is associated with increased intraluminal pressure of the CBD[33]. As mentioned before, we consider MS with a cholecystocholedochal fistula as a progressive disease. Patients with impacted stones at the neck of the gallbladder or the cystic duct have elevated gallbladder pressure. The stones lead to repeated inflammation and necrosis of the gallbladder wall, resulting in a cholecystocholedochal fistula. The pressure in the gallbladder is released, but intraductal pressure of the CBD increases due to stone migration, causing serious bile duct obstruction and suppurative cholangitis. This endoscopic finding has been previously confirmed by intraoperative findings[3].

A major limitation of our study is its retrospective nature. In addition, the number of patients with MS with cholecystocholedochal fistulas were relatively small. The factors that were found in our study should also be verified in future clinical studies.

In conclusion, it is important to establish the preoperative diagnosis of a cholecystocholedochal fistula by ERCP to optimize planning for the surgical procedure in patients with MS. In our series, ERCP provided a predictive factor for cholecystocholedochal fistulas, both endoscopically and by cholangiography. Gall bladder opacification is more frequent is patients with cholecystocholedochal fistula. Pus in the CBD during ERCP is more likely to predict an adverse event with a cholecystocholedochal fistula in patients with MS. However, a stricture longer than 2 cm at the CBD is less likely to predict a cholecystocholedochal fistula in these patients.

The authors would like to thank Professor Teng W for reviewing the result of statistical analysis in this study.

Mirizzi syndrome (MS) is defined as an extrinsic compression of the extrahepatic biliary system by an impacted stone in the gallbladder or the cystic duct leading to obstructive jaundice. Cholecystectomy is a challenging procedure for a laparoscopic surgeon in patients with MS, and the presence of a cholecystocholedochal fistula renders preoperative diagnosis important during endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP).

Our study revealed that gall bladder opacification is more frequent in patients with cholecystocholedochal fistula. Pus in the common bile duct is a predictive factor for the diagnosis of MS with cholecystocholedochal fistulas, and stricture length of the common bile duct longer than 2 cm is a protective factor for cholecystocholedochal fistulas in patients with MS.

This study is a retrospective analysis that aimed to investigate predictive factors for patients with MS with cholecystocholedochal fistulas during ERCP before laparoscopic surgery.

Patients with associated malignancy or those who had already undergone cholecystectomy before ERCP were excluded. In total, 117 patients with MS diagnosed by ERCP were enrolled in this study. The clinical data, cholangiography, and endoscopic findings during ERCP were recorded and analyzed.

Gallbladder opacification on cholangiography is more frequent in patients with MS complicated by cholecystocholedochal fistulas. Pus in the common bile duct and stricture length of the common bile duct longer than 2 cm were two additional independent factors associated with MS, as demonstrated by multivariate analysis

It is important to establish the preoperative diagnosis of a cholecystocholedochal fistula by ERCP to optimize planning for the surgical procedure in patients with MS. Gall bladder opacification is more frequent is patients with cholecystocholedochal fistula.

The number of patients with MS with cholecystocholedochal fistulas were relatively small. The factors that were found in our study should also be verified in future clinical studies.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Taiwan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Nishida T, Rabago LR, Saito H, Şentürk H S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Mirizzi P. Sindrome del conducto hepatico. J Int Chir. 1948;8:731-777. |

| 2. | McSherry C. The Mirizzi syndrome: suggested classification and surgical therapy. Surg Gastroenterol. 1982;1:219-225. |

| 3. | Csendes A, Díaz JC, Burdiles P, Maluenda F, Nava O. Mirizzi syndrome and cholecystobiliary fistula: a unifying classification. Br J Surg. 1989;76:1139-1143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Elhanafy E, Atef E, El Nakeeb A, Hamdy E, Elhemaly M, Sultan AM. Mirizzi Syndrome: How it could be a challenge. Hepatogastroenterology. 2014;61:1182-1186. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Baer HU, Matthews JB, Schweizer WP, Gertsch P, Blumgart LH. Management of the Mirizzi syndrome and the surgical implications of cholecystcholedochal fistula. Br J Surg. 1990;77:743-745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Katsohis C, Prousalidis J, Tzardinoglou E, Michalopoulos A, Fahandidis E, Apostolidis S, Aletras H. Subtotal cholecystectomy. HPB Surg. 1996;9:133-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lee KF, Chong CN, Ma KW, Cheung E, Wong J, Cheung S, Lai P. A minimally invasive strategy for Mirizzi syndrome: the combined endoscopic and robotic approach. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:2690-2694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lacerda Pde S, Ruiz MR, Melo A, Guimarães LS, Silva-Junior RA, Nakajima GS. Mirizzi syndrome: a surgical challenge. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2014;27:226-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yonetci N, Kutluana U, Yilmaz M, Sungurtekin U, Tekin K. The incidence of Mirizzi syndrome in patients undergoing endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2008;7:520-524. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Kiriyama S, Kozaka K, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Pitt HA, Gabata T, Hata J, Liau KH, Miura F, Horiguchi A, Liu KH, Su CH, Wada K, Jagannath P, Itoi T, Gouma DJ, Mori Y, Mukai S, Giménez ME, Huang WS, Kim MH, Okamoto K, Belli G, Dervenis C, Chan ACW, Lau WY, Endo I, Gomi H, Yoshida M, Mayumi T, Baron TH, de Santibañes E, Teoh AYB, Hwang TL, Ker CG, Chen MF, Han HS, Yoon YS, Choi IS, Yoon DS, Higuchi R, Kitano S, Inomata M, Deziel DJ, Jonas E, Hirata K, Sumiyama Y, Inui K, Yamamoto M. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: diagnostic criteria and severity grading of acute cholangitis (with videos). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018;25:17-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 468] [Cited by in RCA: 424] [Article Influence: 60.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bollman JL, Mann FC. Peptic ulcer in experimental obstructive jaundice. Arch Surg. 1932;24:126-135. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cingi A, Ahiskali R, Oktar BK, Gülpinar MA, Yegen C, Yegen BC. Biliary decompression reduces the susceptibility to ethanol-induced ulcer in jaundiced rats. Physiol Res. 2002;51:619-627. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Sasaki I, Miyakawa H, Kameyama J, Kamiyama Y, Sato T. Influence of obstructive jaundice on acute gastric ulcer, intragastric pH and potential difference in rats. Tohoku J Exp Med. 1986;150:161-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Cantürk NZ, Cantürk Z, Ozbilim G, Yenisey C. Protective effect of vitamin E on gastric mucosal injury in rats with biliary obstruction. Can J Gastroenterol. 2000;14:499-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Antoniou SA, Antoniou GA, Makridis C. Laparoscopic treatment of Mirizzi syndrome: a systematic review. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:33-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Beltran MA, Csendes A, Cruces KS. The relationship of Mirizzi syndrome and cholecystoenteric fistula: validation of a modified classification. World J Surg. 2008;32:2237-2243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Puestow CB. Spontaneous internal biliary fistulae. Ann Surg. 1942;115:1043-1054. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Binnie NR, Nixon SJ, Palmer KR. Mirizzi syndrome managed by endoscopic stenting and laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 1992;79:647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Paul MG, Burris DG, McGuire AM, Thorfinnson HD, Schönekäs H. Laparoscopic surgery in the treatment of Mirizzi's syndrome. J Laparoendosc Surg. 1992;2:157-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Meng WC, Kwok SP, Kelly SB, Lau WY, Li AK. Management of Mirizzi syndrome by laparoscopic cholecystectomy and laparoscopic ultrasonography. Br J Surg. 1995;82:396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Waisberg J, Corona A, de Abreu IW, Farah JF, Lupinacci RA, Goffi FS. Benign obstruction of the common hepatic duct (Mirizzi syndrome): diagnosis and operative management. Arq Gastroenterol. 2005;42:13-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Karademir S, Astarcioğlu H, Sökmen S, Atila K, Tankurt E, Akpinar H, Coker A, Astarcioğlu I. Mirizzi's syndrome: diagnostic and surgical considerations in 25 patients. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2000;7:72-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yip AW, Chow WC, Chan J, Lam KH. Mirizzi syndrome with cholecystocholedochal fistula: preoperative diagnosis and management. Surgery. 1992;111:335-338. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Costi R, Gnocchi A, Di Mario F, Sarli L. Diagnosis and management of choledocholithiasis in the golden age of imaging, endoscopy and laparoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:13382-13401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 25. | Beltrán MA. Mirizzi syndrome: history, current knowledge and proposal of a simplified classification. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4639-4650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 26. | Abou-Saif A, Al-Kawas FH. Complications of gallstone disease: Mirizzi syndrome, cholecystocholedochal fistula, and gallstone ileus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:249-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Safioleas M, Stamatakos M, Safioleas P, Smyrnis A, Revenas C, Safioleas C. Mirizzi Syndrome: an unexpected problem of cholelithiasis. Our experience with 27 cases. Int Semin Surg Oncol. 2008;5:12. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Marinov L. The Mirizzi Syndrome -Major Cause for Biliary Duct Injury during Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. Biomed J Sci Tech Res. 2017;1:804-805. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | England RE, Martin DF. Endoscopic management of Mirizzi's syndrome. Gut. 1997;40:272-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Rhodes M, Sussman L, Cohen L, Lewis MP. Randomised trial of laparoscopic exploration of common bile duct versus postoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiography for common bile duct stones. Lancet. 1998;351:159-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 329] [Cited by in RCA: 288] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 31. | Palazzo L, Girollet PP, Salmeron M, Silvain C, Roseau G, Canard JM, Chaussade S, Couturier D, Paolaggi JA. Value of endoscopic ultrasonography in the diagnosis of common bile duct stones: comparison with surgical exploration and ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:225-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Bhandari S, Bathini R, Sharma A, Maydeo A. Usefulness of single-operator cholangioscopy-guided laser lithotripsy in patients with Mirizzi syndrome and cystic duct stones: experience at a tertiary care center. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84:56-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Csendes A, Sepúlveda A, Burdiles P, Braghetto I, Bastias J, Schütte H, Díaz JC, Yarmuch J, Maluenda F. Common bile duct pressure in patients with common bile duct stones with or without acute suppurative cholangitis. Arch Surg. 1988;123:697-699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |