Published online Jan 14, 2020. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i2.184

Peer-review started: October 8, 2019

First decision: November 11, 2019

Revised: December 14, 2019

Accepted: December 21, 2019

Article in press: December 21, 2019

Published online: January 14, 2020

Processing time: 97 Days and 8.2 Hours

The expression of the membrane receptor protein GFRA1 is frequently upregulated in many cancers, which can promote cancer development by activating the classic RET-RAS-ERK and RET-RAS-PI3K-AKT pathways. Several therapeutic anti-GFRA1 antibody-drug conjugates are under development. Demethylation (or hypomethylation) of GFRA1 CpG islands (dmGFRA1) is associated with increased gene expression and metastasis risk of gastric cancer. However, it is unknown whether dmGFRA1 affects the metastasis of other cancers, including colon cancer (CC).

To study whether dmGFRA1 is a driver for CC metastasis and GFRA1 is a potential therapeutic target.

CC and paired surgical margin tissue samples from 144 inpatients and normal colon mucosal biopsies from 21 noncancer patients were included in this study. The methylation status of GFRA1 islands was determined by MethyLight and denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography and bisulfite-sequencing. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to explore the effect of dmGFRA1 on the survival of CC patients. Impacts of GFRA1 on CC cell proliferation and migration were evaluated by a battery of biological assays in vitro and in vivo. The phosphorylation of AKT and ERK proteins was examined by Western blot analysis.

The proportion of dmGFRA1 in CC, surgical margin, and normal colon tissues by MethyLight was 68.4%, 73.4%, and 35.9% (median; nonparametric test, P = 0.001 and < 0.001), respectively. Using the median value of dmGFRA1 peak area proportion as the cutoff, the proportion of dmGFRA1-high samples was much higher in poorly differentiated CC samples than in moderately or well-differentiated samples (92.3%% vs 55.8%, Chi-square test, P = 0.002) and significantly higher in CC samples with distant metastasis than in samples without (77.8% vs 46.0%, P = 0.021). The overall survival of patients with dmGFRA1-low CC was significantly longer than that of patients with dmGFRA1-high CC (adjusted hazard ratio = 0.49, 95% confidence interval: 0.24-0.98), especially for 89 CC patients with metastatic CC (adjusted hazard ratio = 0.41, 95% confidence interval: 0.18-0.91). These data were confirmed by the mining results from TCGA datasets. Furthermore, GFRA1 overexpression significantly promoted the proliferation/invasion of RKO and HCT116 cells and the growth of RKO cells in nude mice but did not affect their migration. GFRA1 overexpression markedly increased the phosphorylation levels of AKT and ERK proteins, two key molecules in two classic GFRA1 downstream pathways.

GFRA1 expression is frequently reactivated by DNA demethylation in CC tissues and is significantly associated with a poor prognosis in patients with CC, especially those with metastatic CC. GFRA1 can promote the proliferation/growth of CC cells, probably by the activation of AKT and ERK pathways. GFRA1 might be a therapeutic target for CC patients, especially those with metastatic potential.

Core tip: GFRA1 reactivation by DNA demethylation is a frequent event in colon cancer (CC) development and that the high level of GFRA1 demethylation in CC tissues is correlated with high metastasis risk of CC and shorter overall survival of patients, especially patients with metastatic CC. We find that GFRA1 overexpression enhances the proliferation and growth of CC cells in vitro and in vivo, probably by activation of the GFRA1-GDNF downstream pathway. These data indicate that reactivation of GFRA1 by DNA demethylation is an important prognosis factor for CC and the cancer-related cell membrane protein GFRA1 may be a therapeutic target for CC patients.

- Citation: Ma WR, Xu P, Liu ZJ, Zhou J, Gu LK, Zhang J, Deng DJ. Impact of GFRA1 gene reactivation by DNA demethylation on prognosis of patients with metastatic colon cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2020; 26(2): 184-198

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v26/i2/184.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v26.i2.184

Although advances have been made in the treatment of colorectal carcinoma (CRC), it remains the most common gastrointestinal cancer worldwide[1]. CRC is annually diagnosed in 1.4 million individuals and leads to 700000 deaths worldwide[2]. Metastasis is the leading cause of CRC-related death[3]. Although the biological mechanisms associated with CRC metastasis have been extensively studied[4], the sensitivity and specificity of existing clinical biomarkers for predicting the prognosis of CRC patients are not satisfactory. Recognition of specific biomarkers is important for predicting prognosis, including metastasis, of colorectal cancer. Molecular therapy targets for patients with metastatic CRC are also urgently needed.

GFRA1 is a cell surface membrane receptor for glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF)[5,6]. The GDNF-GFRA1 complex binds to and activates the tran-smembrane RET proto-oncogene receptor, induces the phosphorylation of RET tyrosine residues, and activates the RAS-ERK and PI3K-AKT signaling pathways, thus mediating the development of the nervous system and kidneys, as well as cancer growth[6-9]. The GFRA1 gene is not only normally expressed in neural cells, especially in enteric neurons, but is also abnormally overexpressed in many cancers[9-17]. GFRA1 overexpression can affect multiple biological behaviors of cancer cells, including proliferation, metastasis, and perineural invasion. GFRA1 overexpression is associated with a poor overall survival (OS) of patients with pancreatic or breast cancer[12,16]. Anti-GFRA1 autoantibodies can be detected in patients with luminal A (hormone receptor-positive) breast cancer[18,19]. Apparently, the cancer-associated GFRA1 protein is a potential therapeutic target. Several preclinical anti-GFRA1 antibody-drug conjugates for breast cancer treatment have been developed[20,21].

It is well known that the methylation of CpG islands around the transcription start site (TSS-CGIs) epigenetically inactivates gene transcription, and TSS-CGI demethylation is essential for methylated gene reactivation. Our recent studies have shown that GFRA1 alleles are epigenetically silenced by the methylation of GFRA1 TSS-CGI (mGFRA1) in many normal non-nervous cells in adult tissues and are abnormally reactivated in cancer cells by the demethylation (or hypomethylation) of the GFRA1 TSS-CGI (dmGFRA1)[22]. The presence of dmGFRA1 was consistently found to be associated with an increased metastasis risk of gastric carcinoma and short OS in multiple cohorts in China, Japan, and Korea[22]. The results of our prospective study further showed that dmGFRA1 could be a potential biomarker for prediction of metastasis of gastric carcinoma in Chinese patients[23]. However, no studies have reported the impacts of the reactivation of GFRA1 expression by dmGFRA1 on CRC progression.

In this study, we examined the demethylation status of TSS-CGIs in GFRA1 alleles in colon carcinoma (CC) and paired surgical margin (SM) tissue samples and normal colon mucosal biopsy samples from noncancer patients. We observed that GFRA1 was significantly demethylated in both CC and SM tissues compared with that in normal colon biopsies and that the high dmGFRA1 level was significantly correlated with poor differentiation, metastasis, and short OS for CC patients, especially those with metastatic CC. GFRA1 overexpression could promote the proliferation/growth of CC cells in vitro and in vivo, probably by increasing the phosphorylation levels of two key proteins ERK and AKT in two classical GDNF-GFRA1 downstream pathways in CC cells.

CC and paired SM (> 5 cm from the cancerous mass) tissue samples and related clinicopathological information were obtained from 144 patients at Peking University Cancer Hospital. Normal colon mucosal biopsies from 21 noncancer patients from the same hospital were also included in this study. The Institutional Review Board of the Peking University Cancer Hospital and Institute approved the study, and all of the patients provided written informed consent.

The human CC cell line HCT116 was kindly provided by Professor Yuanjia Chen at Peking Union Medical College Hospital, and RKO was purchased from American Type Culture Collection. The HEK293FT cell line was provided by Dr. Zhang ZQ at Peking University Cancer Hospital and Institute. These cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, GrandIsland, NY, United States) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco), and maintained at 37 °C in a 5% CO2-containing atmosphere. These cell lines were tested and authenticated by Beijing JianLian Genes Technology Co., LTD before they were used in this study. STR patterns were analyzed using the Goldeneye 20A STR Identifiler PCR Amplification Kit as we previously reported[22].

More human cell lines were used in the pilot study, including the gastric cell lines BGC823, GES1, MGC803, and SGC7901, cervical cancer cell lines HeLa and Siha, and breast cancer cell line MCF7, kindly provided by Dr. Yang K; the gastric cancer cell line AGS and lung cancer cell line H1299 provided by Dr. Shou CC; the lung cancer cell line A549 provided by Dr. Zhang ZQ at Peking University Cancer Hospital; the gastric cell line MKN74 provided by Dr. Yashuhito Y at Tokyo Medical and Dental University; the prostate cancer cell line PC-3 purchased from Cell Line Bank, Chinese Acad Med Sci; the liver cancer cell line HepG2 provided by Dr. Zhang ZQ; the gastric cancer cell line MKN45 purchased from National Laboratory Cell Resource Sharing Platform; and the colon cancer (CC) cell lines Colo205 and SW480 provided by Professor Chen YJ at Peking Union Medical College Hospital. A549, BGC823 GES1, H1299, HepG2, MGC803, MKN45, MKN74, and SGC7901 cells were cultured in RPMI1640 medium with 10% FBS. Colo205, HeLa, MCF7, Siha, and SW480 cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS. AGS and PC3 cells were cultured in F12 medium with 10% FBS. AGS and PC3 cells were cultured in F12 medium with 10% FBS.

The methylation information on 31 CpG sites within the GFRA1 TSS-CGI (by the 450K methylation array) in CC and SM samples from 268 of 454 patients and related clinical information were downloaded from the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database. OS information was available for 190 patients. The methylation level for each CpG site was expressed using the β value, calculated as M/(M+U), where M is the signal from methylated beads, and U is the signal from unmethylated beads at the targeted CpG site. When the β value for a CpG site was < 0.2, it was classified as demethylation-positive CpG (dmCpG). The total number of dmCpG sites was used to represent the GFRA1 demethylation level for each sample. The median dmCpG number of 2 for the 268 samples was used as the cutoff value to define dmGFRA1. A sample containing ≥ 2 dmCpG sites was classified as dmGFRA1-high; otherwise, dmGFRA1-low (Table S1). The information on the GFRA1 mRNA level in CC samples from 453 patients was also downloaded from the TCGA database. The OS information for 350 patients was used in the online OS analysis at the website (bioinformatica. Mty.itesm.mx: 8080/Biomatec/SurvivaX.Jsp)[24].

GFRA1 transcript isoform b (GFRA1b, 1380 nt) is the main mature mRNA for this gene in cancer[7,25]. Therefore, the full-length human GFRA1b viral expression vector supernatant (pLenti-GFRA1b) was purchased from Obio Technology Corp (Cat. no.CK1116, Shanghai, China). The GFRA1b expression viral supernatant or mock viral supernatant control was used to transfect HCT116 and RKO cells following the manufacturer’s instructions. To obtain stably-transfected cells, we selected the transfected cells by culturing them in medium containing 0.5 μg/mL puromycin (Sigma, St Louis, MO, United States) for at least two weeks after transfection.

Total RNA was extracted using the Ultrapure RNA Kit (Beijing ComWin Biotech Co., Ltd, China) and the quality and concentration of RNA samples were monitored using the Nanodrop 2000 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States). Qualified RNA samples were used to synthesize cDNA using the Trans-Script First-Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China). GFRA1 mRNA 150-bp amplicon was detected by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) using a primer set (forward, 5’-GATATATTCC GGGTGGTCCC ATTC-3’, and reverse 5’-GGTGCACGGG GTGATGTACGC-3’) and SYBR Green PCR master mix reagents (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) at an annealing temperature of 58.5 °C on an ABI-7500 platform[22]. GFRA1 mRNA levels were normalized to Alu reference RNA as previously reported[25,26]. The relative mRNA level was calculated using the classic ΔΔCt method. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate.

Genomic DNA was extracted using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Cat# 51306, Hiden, Germany). Bisulfite conversion was performed by adding 5 M sodium bisulfite to 1.8 μg DNA samples[27].

A CpG-free universal primer set (forward, 5’-GGTGTTGGAA ATTTTTTAAAGG-3’ and reverse, 5’-AAAACACTTC TTCCTTCCACAT-3’) and bisulfite-modified DNA were used to amplify both methylated and demethylated GFRA1 TSS-CGIs at an annealing temperature of 55.0 °C[22]. The PCR products were clone-sequenced and then analyzed quantitatively by denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography (DHPLC) using the WAVE DNA Fragment Analysis System[22,28]. Briefly, 522-bp PCR products of methylated and demethylated GFRA1 were separated using a DNASep analytical column (Transgenomic) at a partial denaturing temperature of 55.5 °C. Genomic DNA obtained from blood samples with and without M.sssI methylation was used as the mGFRA1- and dmGFRA1-positive controls, respectively. The peak areas corresponding to the mGFRA1 and dmGFRA1 products were used to calculate the proportion of dmGFRA1 (the proportion of dmGFRA1-peak area = dmGFRA1-peak area/the sum of the dmGFRA1-peak and mGFRA1-peak areas). When a dmGFRA1-peak was detected in a sample, it was defined as dmGFRA1-positive sample; otherwise, dmGFRA1-negative (Table S1).

The dmGFRA1 levels in all of tissue samples were detected with the MethyLight assay, a previously established and optimized quantitative assay at our lab[22,27]. The median value of dmGFRA1 proportion for CC tissue samples was used as the cutoff to define dmGFRA1-high and dmGFRA1-low CC (Table S1).

Cells were collected and lysed to obtain protein lysates. The resulting proteins were then electrophoresed using a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred onto a PVDF membrane. After blocking with 5% nonfat milk overnight at 4 °C, the membrane was incubated with the corresponding primary antibodies [anti-GFRA1 (AF714), R&D systems, Minneapolis, United States; anti-GAPDH (60004-1), Protein Tech, China; anti-ERK (4695S), anti-p-ERK (4370S), anti-AKT (4691T), and anti-p-AKT (4060T), Cell Signaling Technology, United States] for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane was then washed three times with PBST (PBS with 0.1% Tween-20). After washing, the membrane was incubated with the corresponding horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-goat or mouse IgG at room temperature for 1 h. Signals were visualized using the Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate Kit (Millipore, United States).

HCT116 and RKO cells were seeded in 96-well plates (2000 cells/well, 5 wells/group) and cultured for at least 96 h to obtain the proliferation curves. Cells were photographed every 6 h in a long-term dynamic observation platform (IncuCyte, Essen, MI, United States). Cell confluence was analyzed using IncuCyte ZOOM software (Essen, Ann Arbor, MI, United States). For continuous observation of cell migration, the cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 10000 cells/well and cultured for 24 h. After a scratch wound was created, the cells were washed three times with PBS. The cells were regularly cultured and photographed every 6 h for at least 96 h. The relative wound width was calculated using the same software[29].

RKO cells stably transfected with the control or GFRA1b expression vector were trypsinized, washed twice with PBS, and then subcutaneously injected into the bilateral inguinal regions of female BALB/c mice (body weight 18-20 g; age 6 weeks, Beijing Huafukang Bioscience Co. Inc.; 2 × 106 cells per injection). There were eight mice in each experimental group. On the 29th day post-transplantation, the mice were sacrificed. The tumors were then removed from the mice and weighed.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 18.0 software. The Mann–Whitney U-test was conducted for non-normally distributed data. Student’s t-test was used for normally distributed data. The log-rank test was used to compare survival durations between groups. All statistical tests were two-sided, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

To study the relationship between dmGFRA1 and GFRA1 mRNA levels, we first analyzed the demethylation status of GFRA1 CpG islands in a set of cancer cell lines (n = 20). The peak for dmGFRA1 products was detected in seven cell lines (GES1, HEK293T, PC3, MCF7, A549, and HepG2) using the DHPLC analysis (Figure 1A). Bisulfite sequencing confirmed the DHPLC results (Figure 1B). High levels of GFRA1 mRNA were detected in five dmGFRA-positive cell lines but not in 15 dmGFRA1-negative cell lines (including the four CC cell lines Colo205, HCT116, RKO, and SW480) (P < 0.001, Figure 1C). Correlation analysis showed that the dmGFRA1 proportion was positively and significantly correlated with the GFRA1 mRNA levels in these cell lines (Spearman’s test, R = + 0.33, P = 0.041, Figure 1D). This was confirmed by bioinformatics analysis using TCGA demethylation and expression datasets for 267 CC patients: Higher levels of GFRA1 mRNA were detected in dmGFRA1-high CC samples than in dmGFRA1-low CC samples (P = 0.005, Figure S1).

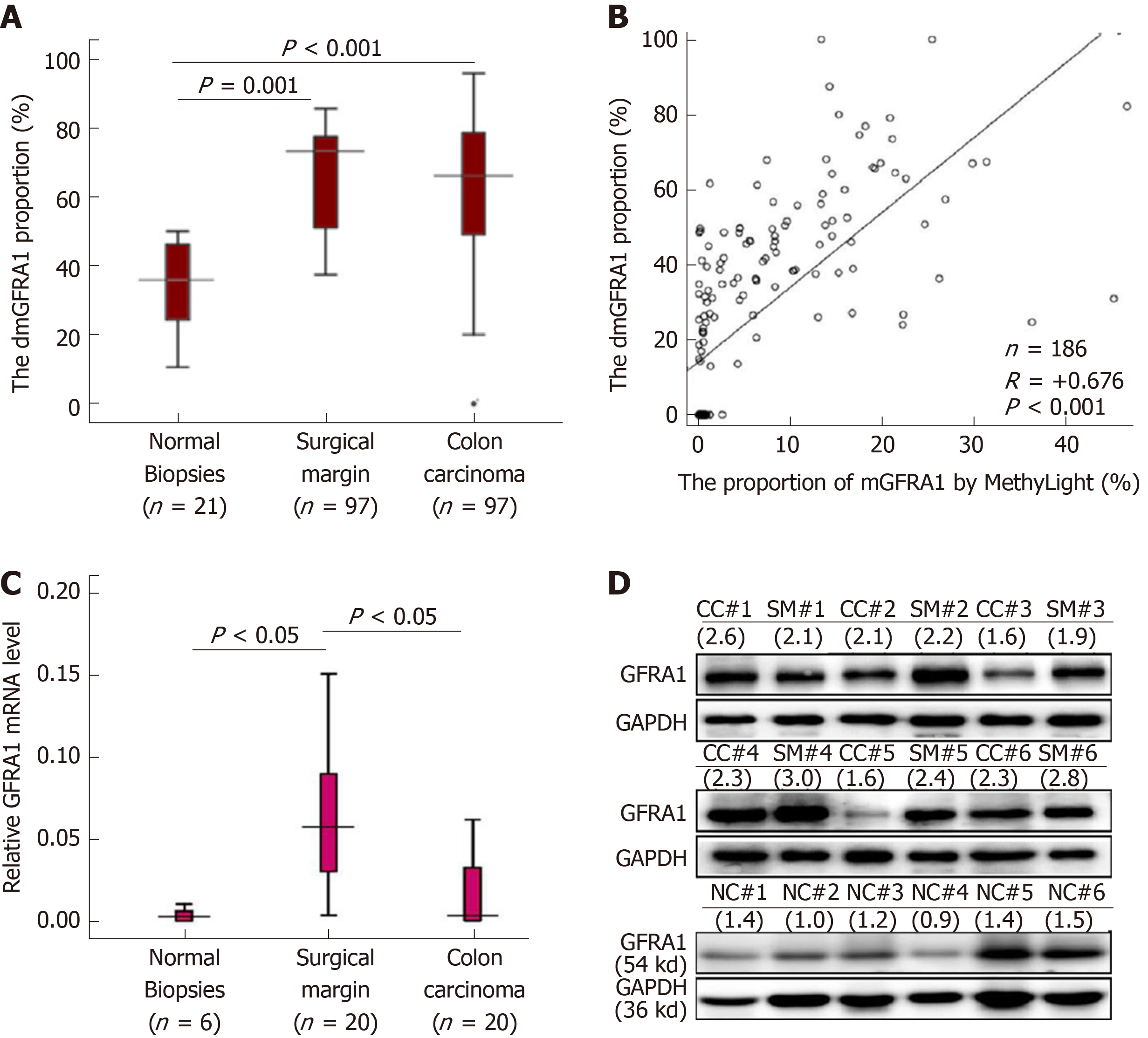

Then, a MethyLight assay established by us was used to determine the dmGFRA1 proportion in tissue samples. Compared with that in the normal colon biopsies from noncancer patients (n = 21), the dmGFRA1 peak area proportion in CC and SM samples from inpatients (n = 97) was significantly increased (median: 35.9% vs 68.4% vs 73.4%; Mann-Whitney U-test, P = 0.001 and < 0.001, Figure 2A). The DHPLC results were confirmed by MethyLight analysis (Pearson correlation: R = + 0.676, P < 0.001, Figure 2B). Bisulfite-sequencing confirmed these results of five representative CC samples (Figure S2). The mRNA and protein levels of the GFRA1 gene were significantly higher in the representative SM samples than in the normal biopsies (Figure 2C and 2D). Interestingly, the dmGFRA1, mRNA, and protein levels for the GFRA1 gene in the SM samples were slightly higher than those in the CC samples. According to the publicly available human protein atlas database[30], relative to the normal colon mucosa, GFRA1 protein was mainly increased in the cytoplasm of stromal cells in immunohistochemical staining analysis (Figure S3). These results indicate that dmGFRA1 is a prevalent event in CC development and is associated with increased gene expression.

To study the impact of dmGFRA1 on metastasis of CC, CC and paired SM tissue samples from total 144 inpatients were included in this study. Higher dmGFRA1 levels (by MethyLight) were detected in poorly differentiated CC tissues than in moderately or well-differentiated CC tissues (Mann-Whitney U-test, P < 0.001, Table S2). To better demonstrate the demethylation difference for the GFRA1 gene between CC patients with different clinicopathological characteristics and to characterize survival factors, we further subclassified these patients into dmGFRA1-high and dmGFRA1-low groups using the median dmGFRA1 proportion as the cutoff value. The proportion of dmGFRA1-high samples remained significantly higher in the poorly differentiated CC samples than in the moderately or well-differentiated CC samples (92.3% vs 45.8%, Chi-square test, P = 0.002, Table 1). Most importantly, the proportion of dmGFRA1-high samples was significantly higher in CC tissues with distant metastasis than in those without (P = 0.021, Table 1). A similar difference was also found between CC tissues with and without lymphatic metastasis (P = 0.134). This suggests that GFRA1 reactivation by DNA demethylation may favor CC metastasis.

| dmGFRA11-high cases | dmGFRA1-low cases | dmGFRA1-high proportion (%) | P value1 | ||

| Age (yr) | < 60 | 35 | 25 | 58.3 | 0.091 |

| ≥ 60 | 37 | 47 | 44.0 | ||

| Sex | Male | 42 | 46 | 47.7 | 0.494 |

| Female | 30 | 26 | 53.6 | ||

| Location | Sigmoid | 33 | 40 | 45.2 | 0.243 |

| Others | 39 | 32 | 54.9 | ||

| Differentiation | Poor | 12 | 1 | 92.3 | 0.0022 |

| Moderate/well | 62 | 69 | 45.8 | ||

| Vascular embolus | Negative | 58 | 65 | 47.2 | 0.098 |

| Positive | 14 | 7 | 66.7 | ||

| pTNM stage | I/II | 33 | 39 | 45.8 | 0.314 |

| III/IV | 38 | 32 | 54.3 | ||

| Local invasion | T1-2 | 5 | 6 | 45.5 | |

| T3 | 44 | 27 | 62.0 | 0.0043 | |

| T4 | 22 | 38 | 36.7 | ||

| Lymphatic metastasis | N0 | 32 | 41 | 43.8 | 0.134 |

| N1-3 | 40 | 31 | 56.3 | ||

| Distant metastasis | M0 | 58 | 68 | 46.0 | 0.0212 |

| M1 | 14 | 4 | 77.8 |

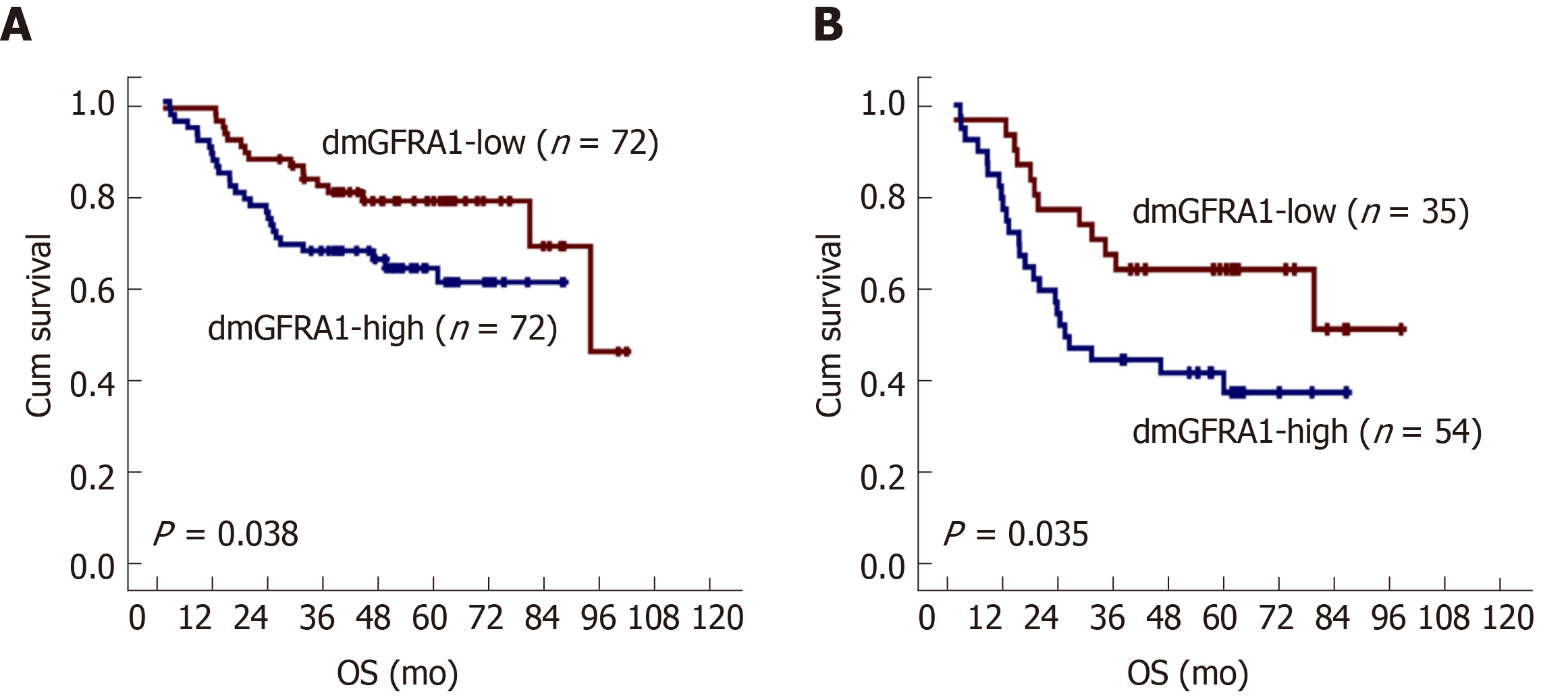

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed that patients with dmGFRA1-high CC had a shorter OS than patients with dmGFRA1-low CC (log-rank test, P = 0.038, Figure 3A). Multivariate analysis showed that dmGFRA1-low CC was an independent favor survival factor after adjustment for age, sex, CC location, differentiation, presence of vascular embolus, local invasion, and metastasis [adjusted hazard ratio (HR) = 0.49, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.24-0.98, P = 0.044, Table 2]. Notably, sub-stratification analysis revealed that dmGFRA1-low CC was also a significant factor for good OS in 89 CC patients with distant or lymphatic metastasis (log-rank test, P = 0.035, Figure 3B; adjusted HR = 0.41, 95%CI: 0.18-0.91, P = 0.029, Table 2).

| All patients (n = 144) | Patients with metastatic CC (n = 89) | |||

| Adjusted HR (95%CI) | P value | Adjusted HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Low dmGFRA1 | 0.49 (0.24-0.98) | 0.044 | 0.41 (0.18-0.91) | 0.029 |

| Age | 1.68 (0.83-3.40) | 0.147 | 1.69 (0.77-3.73) | 0.191 |

| Sex | 1.45 (0.76-2.76) | 0.256 | 1.44 (0.71-2.91) | 0.317 |

| Location | 2.60 (1.32-5.14) | 0.006 | 3.22 (1.48-7.01) | 0.003 |

| Differentiation | 1.95 (0.65-5.89) | 0.235 | 2.02 (0.62-6.61) | 0.246 |

| Vascular embolus | 0.32 (0.15-0.68) | 0.003 | 0.33 (0.15-0.74) | 0.007 |

| Local invasion | 1.27 (0.71-2.28) | 0.421 | 1.16 (0.60-2.24) | 0.668 |

| Metastasis | 4.92 (2.04-11.84) | 0.000 | ||

These data were confirmed by the analysis results using TCGA datasets. Higher levels of GFRA1 mRNA were detected in CC samples with vascular embolus than in those without (Mann-Whitney U-test P = 0.039, Table S3). The proportion of samples with high GFRA1 expression was also slightly higher in CC tissues with distant metastasis than in those without (59.4% vs 47.5%, Chi-square test, P = 0.080). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis indicated that patients with dmGFRA1-high and GFRA1 expression-high CC had a shorter OS than patients with dmGFRA1-low and GFRA1 expression-low CC, but this difference was not statistically significant (Figure S4). Moreover, patients with GFRA1 expression-high CC had a shorter OS than patients with GFRA1 expression-low CC among the 350 CC patients in TCGA (P < 0.005; HR = 2.95, 95%CI: 1.26-4.17, Figure S5).

GFRA1b is the main GFRA1 mRNA isoform in gastrointestinal cancers[25]. To study the effect of GFRA1b on the proliferation and migration of CC cells, we stably transfected RKO and HCT116 cells with human GFRA1b-encoding lentiviral vectors (Figure 4A). The effects of GFRA1b on biological behaviors of cells were examined using a long-term dynamic observation platform (IncuCyte). The results showed that the proliferation of RKO and HCT116 cells was significantly increased by GFRA1b overexpression (Figure 4B). Although GFRA1b overexpression did not affect the migration of these cells based on wound-healing analysis (Figure 4C), however, it promoted the invasion of both cell lines (Figure 4D). Because the GFRA1 gene is silenced by DNA methylation in any of the tested CC cell lines (SW480, Colo205, HCT116, and RKO; Figure 1A and 1B), we did not study the effect of downregulation of GFRA1 expression on the biological behavior of CC cells.

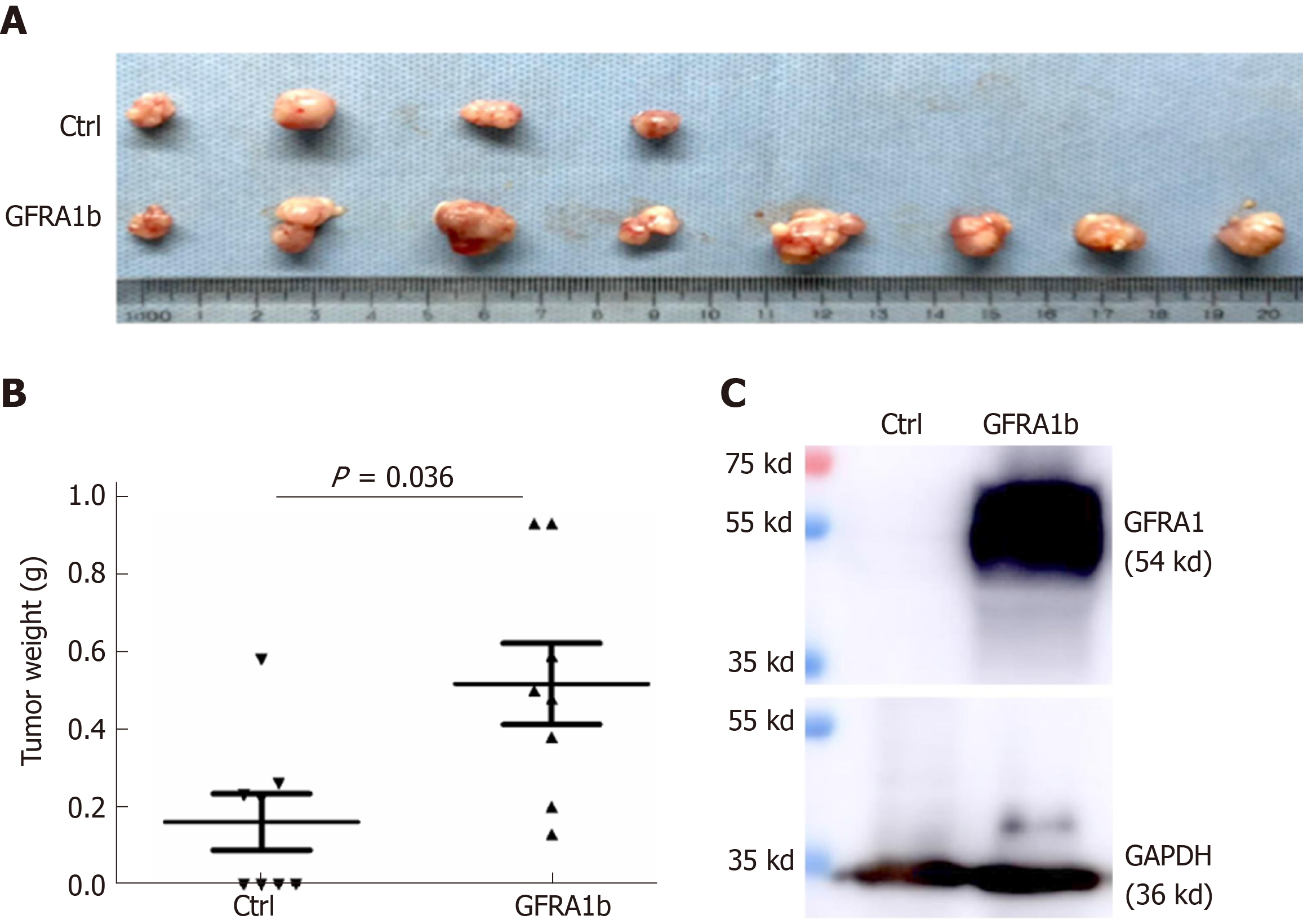

To further investigate whether GFRA1b overexpression could promote the growth of CC cells in vivo, we subcutaneously injected RKO cells stably transfected with the GFRA1b or empty control vector into the bilateral inguinal regions of female BALB/c mice (eight mice per group). Tumor establishment was observed in all eight mice injected with GFRA1b-expressing RKO cells but in only four of eight mice injected with RKO cells without GFRA1b expression on the 29th day post-transplantation (Figure 5A). The average tumor weight in the GFRA1b-expressing group was significantly higher than that in the control group (median, 0.518 g vs 0.161 g, P = 0.036) (Figure 5B). The GFRA1 protein was detected at a high level in a representative tumor from the GFRA1b-expressing group using the Western blot analysis (Figure 5C).

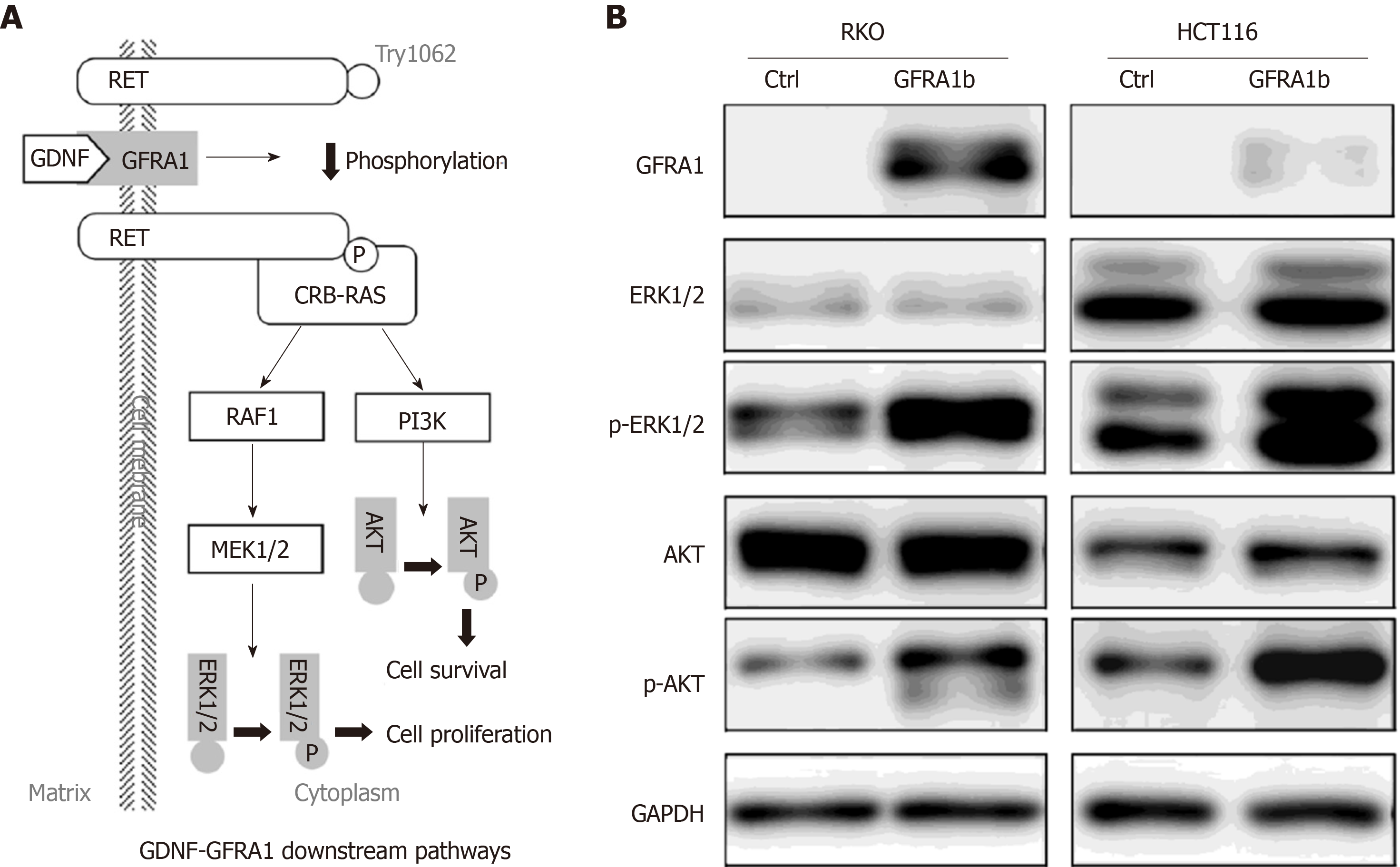

To explore the effect of GFRA1b overexpression on GDNF-GFRA1 downstream signaling pathways in CC cells, we analyzed the phosphorylation status of ERK and AKT proteins, two important molecules in the classic GDNF-GFRA1 downstream pathways (Figure 6A) in RKO and HCT116 cells with and without GFRA1b overexpression. The results of Western blot analysis showed that the phosphorylation levels of ERK and AKT proteins (p-AKT and p-ERK) in the GFRA1b-expressing cells were higher than those in the control cells, although the total amounts of AKT and ERK proteins were not changed in either cell line (Figure 6B). This suggests that overexpression of GFRA1b could increase the phosphorylation levels of ERK and AKT proteins, indicating activation of the GDNF-GFRA1 downstream pathways in CC cells.

GDNF-GFRA1 binding can induce phosphorylation of the RET protein and subsequently activate SRC, MAPK, AKT, Rho, and other downstream signaling pathways to regulate cell survival, differentiation, proliferation, and migration[5-8]. GFRA1 is overexpressed in a variety of cancers and promotes cancer cell proliferation and migration[9-17]. In our recent studies, we consistently found that the GFRA1 gene was abnormally reactivated by TSS-CGI demethylation in gastric carcinomas and this alteration could be used as a biomarker for the prediction of metastasis of gastric carcinoma and OS in Chinese, Japan, and Korean patients in both cross section and prospective cohorts[22,23]. In the present study, we further report that demethylation of GFRA1 TSS-CGIs was a frequent event during CC development and that high dmGFRA1 level could significantly increase the metastasis risk of CC and decrease the OS of patients with metastatic CC, probably by activating the GDNF-GFRA1-RET-RAS pathways.

GDNF-GFRA1 determines enteric neuron number by controlling precursor proliferation[31,32]. Dysfunction and downregulation of the GFRA1 gene can trigger neuronal death in the colon and cause Hirschsprung's disease[33,34]. As a growth factor, the GFRA1 protein also promotes the proliferation and perineural invasion of pancreatic, breast, and bile duct cancer cells[12,16,35]. We found that GFRA1 reactivation by TSS-CGI demethylation was associated with increased CC metastasis risk and decreased OS in patients with metastatic CC, and that GFRA1b overexpression promoted the growth of CC cells and enhanced the phosphorylation levels of the AKT and ERK1/2 proteins. These results suggest that GFRA1 reactivation by DNA demethylation may enhance CC metastasis. Anti-GFRA1 antibody-drug conjugates are under development[20,21]. It is worth studying whether the CC membrane protein GFRA1 may serve as a molecular target for the intervention of CC metastasis using these anti-GFRA1 antibody agents in the future.

Generally, both TSS-CGI methylation and mRNA and protein levels are used to represent the expression states of target genes. It is well recognized that the methylation status of TSS-CGIs is epigenetically maintained in adult human cells and that changes in DNA methylation are more stable than mRNA and protein alterations. TSS-CGI methylation or demethylation changes in a small proportion of the cell population can be very sensitively detected. Thus, DNA methylation alterations may be optimal cancer biomarkers[36]. We previously reported that analysis of the GFRA1 protein in gastric carcinomas from 40 patients in a tissue microarray by immunohistochemical staining failed to demonstrate a statistically significant association of the GFRA1 protein level with clinicopathological parameters and patient OS[22]. By mining the TCGA dataset, we observed that the GFRA1 mRNA level (by cDNA array) was significantly higher in the dmGFRA1-high CC samples (by 450K array) than in the dmGFRA1-low samples (Figure S1) and that high GFRA1 expression was also a significant factor for poor survival in CC patients (n = 350, Figure S5). While fresh/frozen tissue samples should be used to detect the mRNA level of genes, both fresh and paraffin-fixed tissue samples are suitable for methylation analysis of target CpG islands. Interestingly, significant associations of dmGFRA1 (by MethyLight) with CC differentiation, distant metastasis, and OS were successfully demonstrated among 144 patients, implying that dmGFRA1 is a good biomarker.

In the present study, we also found that the upregulation of GFRA1b, the main GFRA1 mRNA isoform in CC tissues, could promote the proliferation or growth of HCT116 and RKO cells in vitro and in vivo. The increased levels of GDNF-GFRA1 downstream phosphoproteins, p-AKT and p-ERK1/2, in GFRA1b-expressing HCT116 and RKO cells indicate that activation of the MAPK signaling pathways by the GFRA1 protein may contribute to the enhancement of proliferation in CC cells.

Compared to other studies, our study is the only one that focused on correlation between the dmGFRA1 level and CC metastasis. One of the limitations of our study is that we did not interfere with the expression of GFRA1 to observe changes of biological behavior by downregulation of GFRA1 expression, because none of tested colon cell lines highly express GFRA1. Effect of GFRA1 reactivation by dmGFRA1 on CC metastasis should be confirmed in animal models.

In addition, it was reported that, in addition to CpG methylation, non-CpG methylation was also correlated with gene expression and prognosis of diseases[37-39]. Non-CpG demethylation (or hypomethylation) changes in the GFRA1 gene was not analyzed in the present study.

In this study, we found that DNA demethylation of GFRA1 TSS-CGIs was associated with the reactivation of gene expression, CC metastasis, and OS of patients. High dmGFRA1 level is a potential biomarker for predicting the prognosis of patients with metastatic CC. A prospective study is expected to confirm our present findings. In addition, it is worth further studying whether dysfunctions of the GFRA1 protein by antibody could prevent metastasis in CC patients.

The membrane receptor protein GFRA1 is normally expressed in neural cells in many organs, including the colon. The GFRA1 gene is abnormally and frequently expressed in cancer cells. Anti-GFRA1 autoantibodies can be detected in patients with breast cancer. Several preclinical anti-GFRA1 antibody-drug conjugates for breast cancer treatment have been developed.

Recently, we reported that the GFRA1 gene is reactivated by DNA demethylation in gastric cancer, which could be used to predict cancer metastasis. Because GFRA1 is normally expressed in neural cells in the colon, it is interesting to study whether GFRA1 reactivation by DNA demethylation is associated with colon cancer (CC) progression and can be used as a therapy target.

To study whether abnormal GFRA1 demethylation is a driver for CC metastasis and the membrane protein GFRA1 is a potential therapeutic target.

CC tissues from 144 patients were included in this study. The level of GFRA1 demethylation was analyzed by quantitative methylation-specific PCR and bisulfite-sequencing. A set of in vitro and in vivo experimental assays were used to evaluate the effect of abnormal GFRA1 expression on CC development.

The level of GFRA1 demethylated alleles was significantly increased during CC development and positively associated with poor CC differentiation, distant CC metastasis, and short OS of CC patients. GFRA1 overexpression significantly promoted CC cell proliferation and invasion in vitro and CC growth in nude mice.

GFRA1 is frequently reactivated by DNA demethylation in CC tissues. GFRA1 demethylation may be a driver for CC development. GFRA1 protein might be a therapeutic target for CC patients, especially those with metastatic potential.

A prospective study is expected to confirm our present findings. It is worth further studying whether dysfunctions of the GFRA1 protein by antibody could prevent CC metastasis.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kim SY, Lucarelli M S-Editor: Wang J L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Mercier J, Voutsadakis IA. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Retrospective Series of Regorafenib for Treatment of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2017;37:5925-5934. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, Mathers C, Parkin DM, Piñeros M, Znaor A, Bray F. Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int J Cancer. 2019;144:1941-1953. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3585] [Cited by in RCA: 4901] [Article Influence: 700.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Liu X, Ji Q, Fan Z, Li Q. Cellular signaling pathways implicated in metastasis of colorectal cancer and the associated targeted agents. Future Oncol. 2015;11:2911-2922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Liu E, Kinnebrew G, Li J, Zhang P, Zhang Y, Cheng L, Li L. A Fast and Furious Bayesian Network and Its Application of Identifying Colon Cancer to Liver Metastasis Gene Regulatory Networks. IEEE/ACM Trans Comput Biol Bioinform. 2019;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cacalano G, Fariñas I, Wang LC, Hagler K, Forgie A, Moore M, Armanini M, Phillips H, Ryan AM, Reichardt LF, Hynes M, Davies A, Rosenthal A. GFRalpha1 is an essential receptor component for GDNF in the developing nervous system and kidney. Neuron. 1998;21:53-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 447] [Cited by in RCA: 436] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Airaksinen MS, Saarma M. The GDNF family: signalling, biological functions and therapeutic value. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:383-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1320] [Cited by in RCA: 1370] [Article Influence: 59.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Charlet-Berguerand N, Le Hir H, Incoronato M, di Porzio U, Yu Y, Jing S, de Franciscis V, Thermes C. Expression of GFRalpha1 receptor splicing variants with different biochemical properties is modulated during kidney development. Cell Signal. 2004;16:1425-1434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Parkash V, Leppänen VM, Virtanen H, Jurvansuu JM, Bespalov MM, Sidorova YA, Runeberg-Roos P, Saarma M, Goldman A. The structure of the glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor-coreceptor complex: insights into RET signaling and heparin binding. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:35164-35172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | He R, Liu P, Xie X, Zhou Y, Liao Q, Xiong W, Li X, Li G, Zeng Z, Tang H. circGFRA1 and GFRA1 act as ceRNAs in triple negative breast cancer by regulating miR-34a. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2017;36:145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 274] [Article Influence: 34.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Fan TC, Yeo HL, Hsu HM, Yu JC, Ho MY, Lin WD, Chang NC, Yu J, Yu AL. Reciprocal feedback regulation of ST3GAL1 and GFRA1 signaling in breast cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2018;434:184-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cavel O, Shomron O, Shabtay A, Vital J, Trejo-Leider L, Weizman N, Krelin Y, Fong Y, Wong RJ, Amit M, Gil Z. Endoneurial macrophages induce perineural invasion of pancreatic cancer cells by secretion of GDNF and activation of RET tyrosine kinase receptor. Cancer Res. 2012;72:5733-5743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gil Z, Cavel O, Kelly K, Brader P, Rein A, Gao SP, Carlson DL, Shah JP, Fong Y, Wong RJ. Paracrine regulation of pancreatic cancer cell invasion by peripheral nerves. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:107-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Borrego S, Fernández RM, Dziema H, Japón MA, Marcos I, Eng C, Antiñolo G. Evaluation of germline sequence variants of GFRA1, GFRA2, and GFRA3 genes in a cohort of Spanish patients with sporadic medullary thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2002;12:1017-1022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Frisk T, Farnebo F, Zedenius J, Grimelius L, Höög A, Wallin G, Larsson C. Expression of RET and its ligand complexes, GDNF/GFRalpha-1 and NTN/GFRalpha-2, in medullary thyroid carcinomas. Eur J Endocrinol. 2000;142:643-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wiesenhofer B, Stockhammer G, Kostron H, Maier H, Hinterhuber H, Humpel C. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) and its receptor (GFR-alpha 1) are strongly expressed in human gliomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2000;99:131-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wu ZS, Pandey V, Wu WY, Ye S, Zhu T, Lobie PE. Prognostic significance of the expression of GFRα1, GFRα3 and syndecan-3, proteins binding ARTEMIN, in mammary carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | He S, Chen CH, Chernichenko N, He S, Bakst RL, Barajas F, Deborde S, Allen PJ, Vakiani E, Yu Z, Wong RJ. GFRα1 released by nerves enhances cancer cell perineural invasion through GDNF-RET signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:E2008-E2017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Evans RL, Pottala JV, Egland KA. Classifying patients for breast cancer by detection of autoantibodies against a panel of conformation-carrying antigens. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2014;7:545-555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Evans RL, Pottala JV, Nagata S, Egland KA. Longitudinal autoantibody responses against tumor-associated antigens decrease in breast cancer patients according to treatment modality. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bhakta S, Crocker LM, Chen Y, Hazen M, Schutten MM, Li D, Kuijl C, Ohri R, Zhong F, Poon KA, Go MAT, Cheng E, Piskol R, Firestein R, Fourie-O'Donohue A, Kozak KR, Raab H, Hongo JA, Sampath D, Dennis MS, Scheller RH, Polakis P, Junutula JR. An Anti-GDNF Family Receptor Alpha 1 (GFRA1) Antibody-Drug Conjugate for the Treatment of Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2018;17:638-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bosco EE, Christie RJ, Carrasco R, Sabol D, Zha J, DaCosta K, Brown L, Kennedy M, Meekin J, Phipps S, Ayriss J, Du Q, Bezabeh B, Chowdhury P, Breen S, Chen C, Reed M, Hinrichs M, Zhong H, Xiao Z, Dixit R, Herbst R, Tice DA. Preclinical evaluation of a GFRA1 targeted antibody-drug conjugate in breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2018;9:22960-22975. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Liu Z, Zhang J, Gao Y, Pei L, Zhou J, Gu L, Zhang L, Zhu B, Hattori N, Ji J, Yuasa Y, Kim W, Ushijima T, Shi H, Deng D. Large-scale characterization of DNA methylation changes in human gastric carcinomas with and without metastasis. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:4598-4612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Liu Z, Cheng X, Zhang L, Zhou J, Deng D, Ji J. A panel of DNA methylated markers predicts metastasis of pN0M0 gastric carcinoma: a prospective cohort study. Br J Cancer. 2019;121:529-536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Aguirre-Gamboa R, Gomez-Rueda H, Martínez-Ledesma E, Martínez-Torteya A, Chacolla-Huaringa R, Rodriguez-Barrientos A, Tamez-Peña JG, Treviño V. SurvExpress: an online biomarker validation tool and database for cancer gene expression data using survival analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 510] [Cited by in RCA: 583] [Article Influence: 48.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Peng XU, Liu Z, Wei LI, Wang C, Xiaodan HA, Xie J, Zhang J. The mRNA Expression of Different Splice Variants of GFRa1 in Gastric Cancer and Colon Cancer Development Process. Journal of Shihezi University. 2015;727-731. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 26. | Zheng X, Zhou J, Zhang B, Zhang J, Wilson J, Gu L, Zhu B, Gu J, Ji J, Deng D. Critical evaluation of Cbx7 downregulation in primary colon carcinomas and its clinical significance in Chinese patients. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Liu Z, Zhou J, Gu L, Deng D. Significant impact of amount of PCR input templates on various PCR-based DNA methylation analysis and countermeasure. Oncotarget. 2016;7:56447-56455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Deng D, Deng G, Smith MF, Zhou J, Xin H, Powell SM, Lu Y. Simultaneous detection of CpG methylation and single nucleotide polymorphism by denaturing high performance liquid chromatography. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:E13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Tian W, Du Y, Ma Y, Gu L, Zhou J, Deng D. MALAT1-miR663a negative feedback loop in colon cancer cell functions through direct miRNA-lncRNA binding. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, Sivertsson Å, Kampf C, Sjöstedt E, Asplund A, Olsson I, Edlund K, Lundberg E, Navani S, Szigyarto CA, Odeberg J, Djureinovic D, Takanen JO, Hober S, Alm T, Edqvist PH, Berling H, Tegel H, Mulder J, Rockberg J, Nilsson P, Schwenk JM, Hamsten M, von Feilitzen K, Forsberg M, Persson L, Johansson F, Zwahlen M, von Heijne G, Nielsen J, Pontén F. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science. 2015;347:1260419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7696] [Cited by in RCA: 10536] [Article Influence: 1053.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Gianino S, Grider JR, Cresswell J, Enomoto H, Heuckeroth RO. GDNF availability determines enteric neuron number by controlling precursor proliferation. Development. 2003;130:2187-2198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Nishiyama C, Uesaka T, Manabe T, Yonekura Y, Nagasawa T, Newgreen DF, Young HM, Enomoto H. Trans-mesenteric neural crest cells are the principal source of the colonic enteric nervous system. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:1211-1218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Uesaka T, Jain S, Yonemura S, Uchiyama Y, Milbrandt J, Enomoto H. Conditional ablation of GFRalpha1 in postmigratory enteric neurons triggers unconventional neuronal death in the colon and causes a Hirschsprung's disease phenotype. Development. 2007;134:2171-2181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Camilleri M, Wieben E, Eckert D, Carlson P, Hurley O'Dwyer R, Gibbons D, Acosta A, Klee EW. Familial chronic megacolon presenting in childhood or adulthood: Seeking the presumed gene association. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;31:e13550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Iwahashi N, Nagasaka T, Tezel G, Iwashita T, Asai N, Murakumo Y, Kiuchi K, Sakata K, Nimura Y, Takahashi M. Expression of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor correlates with perineural invasion of bile duct carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;94:167-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Deng D, Liu Z, Du Y. Epigenetic alterations as cancer diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive biomarkers. Adv Genet. 2010;71:125-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Nicolia V, Cavallaro RA, López-González I, Maccarrone M, Scarpa S, Ferrer I, Fuso A. DNA Methylation Profiles of Selected Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines in Alzheimer Disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2017;76:27-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Fuso A, Ferraguti G, Scarpa S, Ferrer I, Lucarelli M. Disclosing bias in bisulfite assay: MethPrimers underestimate high DNA methylation. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0118318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Fuso A, Scarpa S, Grandoni F, Strom R, Lucarelli M. A reassessment of semiquantitative analytical procedures for DNA methylation: comparison of bisulfite- and HpaII polymerase-chain-reaction-based methods. Anal Biochem. 2006;350:24-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |