Published online Apr 28, 2020. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i16.1950

Peer-review started: January 10, 2020

First decision: March 6, 2020

Revised: March 26, 2020

Accepted: April 21, 2020

Article in press: April 21, 2020

Published online: April 28, 2020

Processing time: 108 Days and 14.2 Hours

The effectiveness of colonoscopy strictly depends on adequate bowel cleansing. Recently, a 1 L polyethylene glycol plus ascorbate (PEG-ASC) solution (Plenvu; Norgine, Harefield, United Kingdom) has been introduced on the evidence of three phase-3 randomized controlled trials, but it had never been tested in the real-life.

To assess the effectiveness and tolerability of the 1 L preparation compared to 4 L and 2 L- PEG solutions in a real-life setting.

All patients undergoing a screening or diagnostic colonoscopy after a 4, 2 or 1 L PEG preparation, were consecutively enrolled in 5 Italian centers from September 2018 to February 2019. The primary endpoints of the study were the assessment of bowel cleansing success and high-quality cleansing of the right colon. The secondary endpoints were the evaluation of tolerability, adherence and safety of the different bowel preparations. Bowel cleansing was assessed through the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale. Adherence was defined as consumption of at least 75% of each dose, while tolerability was evaluated through a semi-quantitative scale. Safety was systematically monitored through adverse events reporting.

Overall, 1289 met the inclusion criteria and were enrolled in the study. Of these, 490 patients performed a 4 L-PEG preparation (Selgesse®), 566 a 2 L-PEG cleansing (Moviprep® or Clensia®) and 233 a 1 L-PEG preparation (Plenvu®). Bowel cleansing by Boston Bowel Preparation Scale was 6.5 ± 1.5 overall and 6.3 ± 1.5, 6.2 ± 1.5, 7.3 ± 1.5 (P < 0.001) in the subgroups of 4 L, 2 L and 1 L-PEG preparation, respectively. Cleansing success was achieved in 72.4%, 74.1% and 90.1% (P < 0.001), while a high-quality cleansing of the right colon in 15.9%, 12.0% and 41.4% (P < 0.001) for 4 L, 2 L and 1 L-PEG preparation groups, respectively. The 1 L preparation was the most tolerated compared to the 2 and 4 L-PEG solutions in the absence of serious adverse events within any of the three groups. Multiple regression models confirmed 1 L PEG-ASC preparation as an independent predictor of overall cleansing success, high-quality cleansing of the right colon and of tolerability.

This study supports the effectiveness and tolerability of 1 L PEG-ASC, also showing it is an independent predictor of overall cleansing success, high-quality cleansing of the right colon and of tolerability.

Core tip: The effectiveness of colonoscopy strictly depends on adequate bowel cleansing. Nevertheless, bowel preparation is not always well accepted and tolerated by all patients. Recently, a 1 L polyethylene glycol plus ascorbate solution has been introduced on the evidence of three phase-3 randomized controlled trials, but it had never been tested in the real-life. This prospective, multicenter, observational study performed on 1289 patients undergoing screening or diagnostic colonoscopy, confirmed the effectiveness and tolerability of very low-volume preparation for colonoscopy, also showing that it is an independent predictor of overall cleansing success, high-quality cleansing of the right colon and of tolerability.

- Citation: Maida M, Sinagra E, Morreale GC, Sferrazza S, Scalisi G, Schillaci D, Ventimiglia M, Macaluso FS, Vettori G, Conoscenti G, Di Bartolo C, Garufi S, Catarella D, Manganaro M, Virgilio CM, Camilleri S. Effectiveness of very low-volume preparation for colonoscopy: A prospective, multicenter observational study. World J Gastroenterol 2020; 26(16): 1950-1961

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v26/i16/1950.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v26.i16.1950

Colonoscopy is one of the most widely diffused methods for screening of colorectal cancer (CRC), and regular screening is of primary importance since early detection of the cancer is associated with a long-term reduction of disease incidence and mortality[1,2].

Effectiveness of colonoscopy strictly depends on adequate bowel cleansing, since it can affect the diagnostic accuracy and the adenoma detection rate[3]. Moreover, recent data show that high-quality bowel cleansing is also necessary to improve the detection of sessile serrated polyps[4]. On the contrary, a suboptimal bowel preparation negatively affects the performance of colonoscopy, since it results in the increase of procedural duration, potential greater risks of adverse events (AEs), rescheduling of procedures and higher costs[4-8]. More recent guidelines recommend the use of high volume or low volume polyethylene glycol (PEG) based regimens as well as that of non-PEG-based agents that have been clinically validated for routine bowel preparation, in a split-dose regimen[9]. Nevertheless, many solutions require the ingestion of volumes of up to 4 L, which may reduce patients’ compliance resulting in a suboptimal bowel cleansing that is still reported in about one-quarter of procedures[10]. The same issue has been confirmed by a large Italian study showing that inadequate bowel preparation is found in about 17% of colonoscopies[11], and the results from the United Kingdom screening program show that more than 20% of incomplete procedures are caused by poor preparation[12].

A very low-volume 1 L PEG plus ascorbate (PEG-ASC) solution (Plenvu; Norgine, Harefield, United Kingdom) has been recently introduced on the market to improve patients’ experience in colonoscopy by reducing the total intake of liquids to be consumed.

Development of this very low volume 1 L preparation was made possible by increasing the content of ascorbate, which enhances the laxative effect, permitting the delivery of the solution in a smaller volume.

After the evidence from a first phase-2 study[13], three parallel phase-3 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing effectiveness of 1 L PEG-ASC vs trisulfate (NOCT)[14], sodium picosulfate plus magnesium citrate (DAYB)[15] and 2 L PEG (MORA)[16] have been conducted, showing a non-inferiority respect to comparators.

Nevertheless, despite positive data from RCTs, this product has never been tested in a real-life setting, where patients’ characteristics may differ from those of RCTs volunteers, and where the incidence of AEs may even be higher.

This is a prospective, multicenter, commercially unfunded, observational study performed across 5 Italian Gastroenterology and Endoscopy units.

All men and women, in- and out-patients aged > 18 years old undergoing a screening, surveillance or diagnostic colonoscopy, after an afternoon-only or afternoon-morning preparation with 4 L-PEG with Selgesse (Alfasigma, Milan, Italy), 2 L-PEG with Moviprep (Norgine, Harefield, United Kingdom) or Clensia (Selgesse, Alfasigma, Milan, Italy) and 1 L-PEG with Plenvu (Norgine, Harefield, United Kingdom) were consecutively enrolled from September 2018 to February 2019.

Patients with known or suspected ileus, gastrointestinal obstruction, bowel perforation, toxic colitis, or megacolon, ongoing severe acute inflammatory bowel disease, previous colonic resection, recent or active gastrointestinal bleeding, pregnancy, allergy or hypersensitivity to the product were excluded.

At the time of colonoscopy scheduling, each patient was provided with a form containing the names of the four solutions (Selgesse, Moviprep, Clensia and Plenvu) and, for each, separate instructions for bowel preparation. The solution was independently chosen by the patient based on personal preference, costs, and availability. In the afternoon-morning regimen, all bowel preparations were self-administered taking the first dose the afternoon before the colonoscopy at 6:00 pm ± 2 h, and the second dose at 5:00 am ± 2 h the following morning. In the afternoon-only regimen, bowel preparations were entirely consumed the afternoon before the colonoscopy, taking the first dose at 6:00 pm ± 2 h, and the second dose after an interval of 1-2 h. The 1 L and 2 L-PEG solutions were prepared with 500 mL of additional clear fluids after each dose, and additional clear fluids “ad libitum” were permitted up to two hours before the procedure. A low-fiber diet was recommended in the three days preceding the colonoscopy, while on the day before the colonoscopy, patients were permitted a light breakfast and lunch.

The primary endpoints of the study were the assessment of bowel cleansing success and high-quality cleansing of the right colon. The secondary endpoints were the evaluation of tolerability, adherence and safety of the different bowel preparations.

Bowel cleansing was assessed through the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS), by site unblinded colonoscopists after specific training. A bowel cleansing success was defined as a total BBPS ≥ 6 with a partial BBPS ≥ 2 in each segment and a high-quality cleansing of the right colon as a partial BBPS = 3.

Adherence was defined as consumption of at least 75% of each dose, while tolerability was evaluated through a semi-quantitative scale with a score ranging from 1 to 10 (1 = lowest rank, 10 = highest rank). Safety was systematically monitored through AEs reporting, collected at the pre-colonoscopy interview.

Continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation, and categoric variables were summarized as frequency and percentage. Independent-samples t-test and χ2 test were used for comparison of continuous and categorical variables respectively. Pairwise comparisons were adjusted for multiple testing with Benjamini and Hochberg method. Logistic regression models were performed to assess bowel cleansing success and high-quality cleansing of the right colon and to identify the presence of variables associated with outcomes. A generalized linear model was performed to assess tolerability and identify independent predictors. Variables considered into the models were selected through stepwise model selection by Akaike Information Criterion and guided by clinical relevance.

All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.5.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and the statistical review of the study was performed by a biomedical statistician.

The study received Ethics Committee approval and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and good clinical practice. Patients provided written informed consent.

A total of 1566 consecutive patients were evaluated. Of these, 1289 met the inclusion criteria and were enrolled in the study. The main indication for colonoscopy was screening or surveillance for CRC (57.9%). Overall, 52.8% were male, the mean age was 60.5 ± 14.1, 44.8% of patients were ≥ 65 years old. Hypertension was present in 38.2% of cases, diabetes in 11.2%, obesity in 18.3%, and chronic renal failure in 2.3% of patients.

In the entire cohort, 490 patients performed a 4 L-PEG preparation (Selgesse®), 566 a 2 L-PEG cleansing (Moviprep® or Clensia®) and 233 a 1 L-PEG preparation (Plenvu®). The three populations were homogeneous according to the main characteristics (Table 1).

| Overall (n = 1289) | 4 L PEG (Selgesse®) (n = 490) | 2 L PEG (Moviprep® or Clensia®) (n = 566) | 1 L PEG (Plenvu®) (n = 233) | |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 681 (52.8) | 268 (54.7) | 291 (51.4) | 122 (52.4) |

| Female | 608 (47.2) | 222 (45.3) | 275 (48.6) | 111 (47.6) |

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 60.5 ± 14.1 | 61.1 ± 14.1 | 60.5 ± 13.5 | 59.5 ± 15.9 |

| Age group, n (%) | ||||

| < 65 yr | 708 (55.2) | 259 (53.1) | 318 (56.5) | 131 (56.5) |

| ≥ 65 yr | 575 (44.8) | 229 (46.9) | 245 (43.5) | 101 (43.5) |

| Race group | ||||

| White or Caucasian | 1254 (97.3%) | 479 (97.8%) | 550 (97.2%) | 225 (96.6%) |

| Other | 35 (2.7%) | 11 (2.2%) | 16 (2.8%) | 8 (3.4%) |

| Weight, kg, mean ± SD | 72.3 ± 14.6 | 73.3 ± 14.4 | 72.0 ± 15.4 | 71.1 ± 13.0 |

| Height, cm, mean ± SD | 165.8 ± 9.0 | 165.9 ± 9.8 | 165.6 ± 8.5 | 166.3 ± 8.7 |

| BMI, mean ± SD | 26.2 ± 4.6 | 26.6 ± 4.6 | 26.2 ± 4.9 | 25.6 ± 4.0 |

| Obesity | 236 (18.3%) | 101 (20.6%) | 105 (18.6%) | 30 (12.9%) |

| Chronic constipation | 215 (16.7%) | 84 (17.1%) | 101 (17.8%) | 30 (12.9%) |

| Diabetes | 144 (11.2%) | 68 (13.9%) | 62 (11.0%) | 14 (6.0%) |

| Hypertension | 492 (38.2%) | 218 (44.5%) | 223 (39.4%) | 51 (21.9%) |

| Chronic renal failure | 30 (2.3%) | 11 (2.2%) | 12 (2.1%) | 7 (3.0%) |

| Colonoscopy indication, n (%) | ||||

| Screening | 443 (34.4%) | 159 (32.5%) | 201 (35.5%) | 83 (35.6%) |

| Surveillance | 303 (23.5%) | 128 (26.1%) | 121 (21.4%) | 54 (23.2%) |

| Diagnostic | 543 (42.1%) | 203 (41.4%) | 244 (43.1%) | 96 (41.2%) |

With regard to the preparation regimen, 62.5% of patients performed an afternoon-only and 37.5% an afternoon-morning (split) preparation, with a similar distribution among the three groups. The mean time between the assumption of the last dose and the beginning of the colonoscopy was 11.9 ± 2.8 in the afternoon-only and 4.9 ± 1.8 h in the split group, respectively.

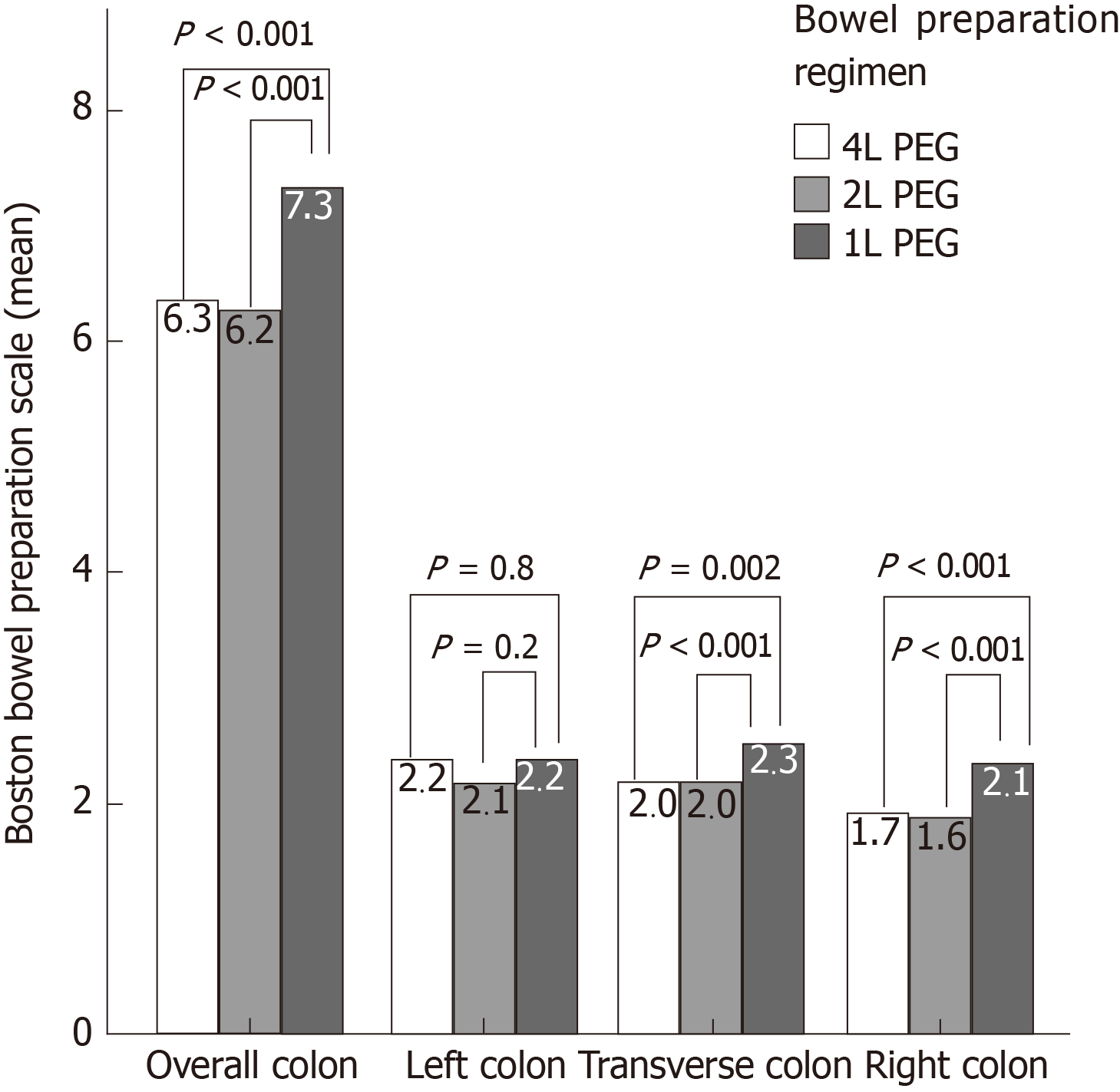

Bowel cleansing by BBPS was 6.5 ± 1.5 overall and 6.3 ± 1.5, 6.2 ± 1.5, 7.3 ± 1.5 (P < 0.001) in the subgroups of 4 L, 2 L and 1 L-PEG preparation, respectively. The average cleansing in the right colon was 1.8 ± 0.6 overall and 1.7 ± 0.6, 1.6 ± 0.6, 2.1 ± 0.6 in the subgroups of 4 L, 2 L, and 1 L-PEG (P < 0.001) (Figure 1).

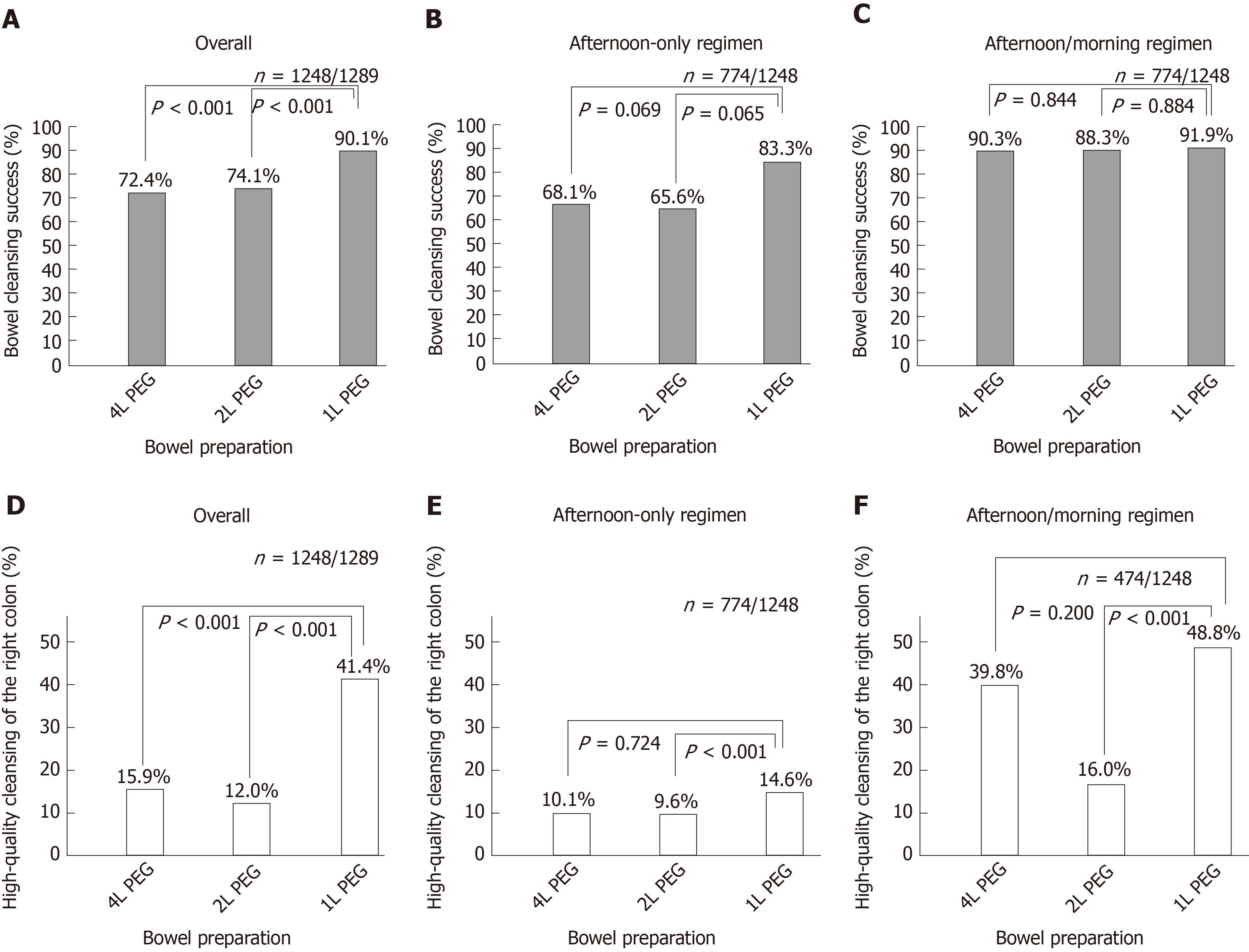

Cleansing success and high-quality cleansing of the right colon were assessed in 1248 out of 1289 patients with a complete colonscopy up to the cecum. An overall cleansing success was achieved in 72.4%, 74.1% and 90.1% (P < 0.001 for 1 L vs 2 L; P < 0.001 for 1 L vs 4 L) of patients after a 4 L, 2 L and 1 L-PEG preparation (Figure 2A). When assessed by preparation modality, cleansing success was 68.1%, 65.6% and 83.3% (P = 0.065 for 1 L vs 2 L; P = 0.069 for 1 L vs 4 L) for afternoon-only preparation and 90.3%, 88.3% and 91.9% (P = 0.84 for 1 L vs 2 L; P = 0.84 for 1 L vs 4 L) for split preparation in the three groups, respectively (Figure 2B and 2C).

A high-quality cleansing of the right colon was achieved in 15.9%, 12.0% and 41.4% (P < 0.001 for 1 L vs 2 L; P < 0.001 for 1 L vs 4 L) of patients after a 4 L, 2 L and 1 L-PEG preparation (Figure 2D). By subgroup analysis, cleansing success was 10.1%, 9.6% and 14.6% (P = 0.72 for 1 L vs 2 L; P = 0.72 for 1 L vs 4 L) in the group of afternoon-only preparation and 39.8%, 16.0% and 48.8% (P < 0.001 for 1 L vs 2 L; P = 0.20 for 1 L vs 4 L) in the group of split preparation in the three groups of 4 L, 2 L and 1 L-PEG preparation (Figure 2E and 2F).

The logistic multiple regression model for overall bowel cleansing success showed that age (OR = 0.99, 95%CI: 0.98-1.00; P = 0.024), absence of diabetes (OR = 1.55, 95%CI: 1.01-2.38; P = 0.046), adequate cleansing at previous colonoscopy (OR = 2.23, 95%CI: 1.30-3.85; P = 0.004), preparation with the 1 L-PEG over the 2 L-PEG (OR = 1.79, 95%CI: 1.04-3.08; P = 0.035), afternoon-morning split regimen (OR = 2.52, 95%CI: 1.62-3.92; P < 0.001), low-fiber diet for at least 3 days preceding colonoscopy (OR = 2.49, 95%CI: 1.71-3.64; P < 0.001), colonoscopy within 5 h after the end of the preparation (OR = 2.35, 95%CI: 1.34-4.10; P = 0.003) were independently associated with overall bowel cleansing success (Table 2).

| Predictors | Odds ratios | 95%CI | P value |

| Female gender | 1.00 | 0.75-1.34 | 0.975 |

| Age, yr | 0.99 | 0.98-1.00 | 0.024 |

| BMI | 0.98 | 0.95-1.01 | 0.217 |

| Diabetes (absence) | 1.55 | 1.01-2.38 | 0.046 |

| Hypertension | 1.35 | 0.97-1.89 | 0.077 |

| Chronic constipation (absence) | 1.11 | 0.77-1.61 | 0.578 |

| Previous adequate cleansing | 2.23 | 1.30-3.85 | 0.004 |

| Preparation (ref = 4 L PEG) | |||

| 2 L PEG | 0.89 | 0.66-1.20 | 0.458 |

| 1 L PEG | 1.60 | 0.91-2.80 | 0.099 |

| Preparation (ref = 2 L PEG) | |||

| 4 L PEG | 1.12 | 0.83-1.51 | 0.458 |

| 1 L PEG | 1.79 | 1.04-3.08 | 0.035 |

| Afternoon-morning split regimen | 2.52 | 1.62-3.92 | < 0.001 |

| Low fiber diet ≥ 3 d | 2.49 | 1.71-3.64 | < 0.001 |

| Time lag ≤ 5 h | 2.35 | 1.34-4.10 | 0.003 |

The logistic multiple regression model for high-quality cleansing of the right colon showed that absence of diabetes (OR = 1.93, 95%CI: 1.02-3.65; P = 0.043), preparation with the 1 L-PEG both over the 4 L-PEG (OR = 1.58, 95%CI: 1.02-2.44; P = 0.041) and the 2 L-PEG (OR = 3.13, 95%CI: 2.08-4.72; P < 0.001), preparation with the 4 L PEG over the 2 L-PEG (OR = 1.99, 95%CI: 1.35-2.91; P < 0.001), and afternoon-morning split regimen (OR = 3.33, 95%CI: 2.19-5.06; P < 0.001) were independently associated with high-quality cleansing of the right colon (Table 3).

| Predictors | Odds ratios | 95%CI | P value |

| Female Gender | 1.25 | 0.91-1.72 | 0.169 |

| Age, yr | 1.00 | 0.99-1.01 | 0.927 |

| BMI | 0.98 | 0.95-1.02 | 0.336 |

| Diabetes (absence) | 1.93 | 1.02-3.65 | 0.043 |

| Hypertension | 1.00 | 0.69-1.44 | 0.983 |

| Chronic constipation (absence) | 0.70 | 0.47-1.04 | 0.080 |

| Previous adequate cleansing | 1.06 | 0.52-2.18 | 0.863 |

| Preparation (ref = 4 L PEG) | |||

| 2 L PEG | 0.50 | 0.34-0.74 | < 0.001 |

| 1 L PEG | 1.58 | 1.02-2.44 | 0.041 |

| Preparation (ref = 2 L PEG) | |||

| 4 L PEG | 1.99 | 1.35-2.91 | < 0.001 |

| 1 L PEG | 3.13 | 2.08-4.72 | < 0.001 |

| Afternoon-morning split regimen | 3.33 | 2.19-5.06 | < 0.001 |

| Low fiber diet ≥ 3 d | 0.99 | 0.63-1.56 | 0.967 |

| Time lag ≤ 5 h | 1.22 | 0.81-1.83 | 0.337 |

Self-reported adherence to preparation was 95% across all treatment groups and greater for patients undergoing a split vs an afternoon-only preparation (98.3% vs 93.5; P < 0.001).

The adherence was higher, even if not statistically significant, in the group of patients assuming the 1 L-PEG solution compared to the 2 and 4 L solutions and achieved respectively in 98.7%, 95.9% and 93.1% of patients (P = 0.357 for 1 L vs 2 L; P = 0.078 for 1 L vs 4 L) (Figure 3A).

Similarly, tolerability was higher for the 1 L preparation compared to the 2 and 4 L-PEG solutions, with an average score of 7.9 ± 1.3 vs 7.1 ± 2.0 and 7.3 ± 1.9 (P < 0.001 for 1 L vs 2 L; P < 0.001 for 1 L vs 4 L) (Figure 3B). Interestingly, a tolerability rating < 6 was observed in 13.7% and 18.9% of subjects undergoing a 4 and 2 L solution, but only in 3.5% of patients taking a 1 L preparation (P < 0.001).

The multiple regression model showed that female gender (estimate -0.51, 95%CI: -0.72, -0.30; P < 0.001), adequate cleansing at previous colonoscopy (estimate 0.65, 95%CI: 0.19-1.10; P = 0.006), preparation with the 1 L-PEG both over the 4 L-PEG (estimate 0.57, 95%CI: 0.25-0.90; P = 0.001) and the 2 L-PEG (estimate 0.72, 95%CI: 0.41-1.03; P < 0.001) and afternoon-morning split regimen (estimate 0.36, 95%CI: 0.06-0.66; P = 0.019) were independently associated with tolerability of bowel preparation (Table 4).

| Predictors | Estimates | 95%CI | P value |

| Female Gender | -0.51 | -0.72, -0.30 | < 0.001 |

| Age, yr | -0.00 | -0.01-0.01 | 0.858 |

| BMI | -0.00 | -0.02-0.02 | 0.889 |

| Diabetes (absence) | 0.12 | -0.22-0.46 | 0.489 |

| Hypertension | 0.25 | -0.04-0.49 | 0.084 |

| Chronic constipation (absence) | -0.20 | -0.48-0.07 | 0.153 |

| Previous adequate cleansing | 0.65 | 0.19-1.10 | 0.006 |

| Preparation (ref = 4 L PEG) | |||

| 2 L PEG | -0.15 | -0.37-0.08 | 0.204 |

| 1 L PEG | 0.57 | 0.25-0.90 | 0.001 |

| Preparation (ref = 2 L PEG) | |||

| 4 L PEG | 0.15 | -0.08-0.37 | 0.204 |

| 1 L PEG | 0.72 | 0.41-1.03 | < 0.001 |

| Afternoon-morning split regimen | 0.36 | 0.06-0.66 | 0.019 |

| Low fiber diet ≥ 3 d | 0.16 | -0.09-0.41 | 0.219 |

Mild and moderate treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs), considered to be associated with bowel preparation, were reported in 16.8% of patients overall. By subgroup analysis, TEAEs were reported in 18.4%, 15.7%, and 15.9% (P = 0.4) of patients undergoing a 4, 2 and 1 L-PEG preparation, showing no significant difference among the three groups (Supplementary Table 1). The most frequent TEAE was nausea, reported in 5.7% of subjects overall, with a higher incidence of 6.7% in the 4 L group compared to 5.7% and 3.9% of 2 and 1 L groups (P = 0.4 for 4 L vs 2 L; P = 0.1 for 4 L vs 1 L). Vomit was reported in 2.3% of patients, with a significantly higher incidence in the 1 L compared to the 2 and 4 L groups, respectively of 6.0%, 1.4% and 1.6% (P = 0.001 for 4 L vs 1 L; P < 0.001 for 4 L vs 2 L). Abdominal pain was present in 2.0% of cases, and mostly in patients undergoing a 4 L preparation compared to the 2 L and the 1 L group, respectively in 3.1%, 1.8% and 0.4% (P = 0.1 for 4 L vs 2 L; P = 0.02 for 4 L vs 1 L). Dehydration was complained by 0.7% of patients overall, and respectively by 0.8%, 0.4%, and 1.3% of patients in the 4, 2 and 1 L groups (P = 0.3). No severe or serious TEAEs were reported.

Lower volume preparations may enhance patients’ experience in colonoscopy since a reduced liquid intake may be better tolerated. Plenvu has already shown high efficacy in RCTs, with a non-inferiority compared to the higher volume solutions[14-16]. In this large prospective, multicenter observational study, 1 L PEG-ASC confirmed a higher bowel cleansing effectiveness over the comparators both as average BBPS score overall and in the right colon, both as cleansing success rate overall. The 1 L PEG-ASC solution presented a marginally significant superiority for cleansing success in the subgroup of the afternoon-only preparation, but it did not achieve superiority in the afternoon-morning split subgroup, where it was found to be equivalent to the 4 and 2 L solutions. This is probably secondary to the effectiveness of a split modality, widely shown by several lines of evidence, which may smooth out the differences of efficacy between the three solutions. Nevertheless, the multiple regression model showed Plenvu to be an independent predictor of overall success over the 2 L-PEG preparation and, marginally, over the 4 L-PEG solution.

In addition, Plenvu showed a greater high-quality cleansing of the right colon overall and in the subgroups of afternoon-only and afternoon-morning preparations. This is of primary importance since recent data showed that a high-quality cleansing vs adequate cleansing allows doubling the detection rate of high-risk sessile serrated lesions[4]. Of note, multiple regression model confirmed Plenvu to be an independent predictor of high-quality cleansing of the right colon both over the 2 L and the 4 L preparations.

Our study also showed higher adherence to preparation with Plenvu, compared with other groups, even if this superiority was only marginally significant only over the 4 L-PEG and not significant over the 2 L-PEG. This was predictable, as these are the two groups with the most significant difference in terms of total volume (3 L), while the small volume difference between 1 and 2 L solutions can justify a comparable adherence.

Similarly, individual tolerability, based on the patients’ judgment, was higher for Plenvu than for other solutions. To note, insufficient tolerability, defined as a score < 6, was reported in only a small minority of patients undergoing a 1 L-PEG preparation (3.9%), compared to a higher percentage of patients undergoing a 4 L (13.6%) and a 2 L (18.9%) solution.

Finally, multiple regression model, confirmed Plenvu to be an independent predictor of tolerability of bowel preparation both over the 2 L and the 4 L solutions. In particular, the combination of 1 L-PEG solution and of a split regimen showed to provide the highest tolerability. These data are of particular importance since they confirm the theoretical assumption that a lower volume solution is also well tolerated.

Overall, the investigated solutions presented a good safety profile in the absence of significant differences in TEAEs across the three groups. However, the type of AEs was different. Nausea was slightly higher in the group of patients undergoing a 4 L solution, compared to the other two groups, even if this difference was not statistically significant. Similarly, abdominal pain presented a higher incidence in the group of the 4 L-PEG, which was significant only over the 1 L group. This difference is probably secondary to the large volume of the 4 L preparation, over the lower-volume ones, which can cause intestinal distension symptoms.

Conversely, vomit was more frequent for the 1 L solution, with a significantly higher incidence over the other two groups. This higher incidence of vomiting after the consumption of Plenvu is probably secondary to the greater amount of ascorbate, which is present in the second dose. Nevertheless, it is crucial to remark that the intensity of vomit was mild and not able to compromise the tolerability of bowel preparation. As a matter of fact, in our study, Plenvu was the most tolerated solution and it was also found to be an independent predictor of tolerability.

Dehydration symptoms were reported in less than 1.5% of patients, with a comparable incidence between the three groups, and no severe or serious AEs or deaths were registered in the entire cohort. Given the observational nature of our study, an assessment of blood electrolyte or creatinine was not feasible. Despite this, no clinical event attributable to electrolyte imbalance or dehydration was observed in any patient.

This is, at best of our knowledge, the first study assessing the effectiveness and tolerability of Plenvu in the real-life. The major strengths of this study are its prospective and multicenter design, the presence of a large sample size and the comparison of the 1 L-PEG preparation with both the 2 and 4 L-PEG solutions. Nevertheless, this study is limited by a few relevant factors. First of all, the absence of randomization, which guarantees the similarity across the treatment groups, and avoids exposure to potential bias, among all the “allocation of intervention bias”.

Nevertheless, the absence of randomization is secondary to the nature of the study that was explicitly intended to be observational. This provides the advantage to evaluate the effectiveness and the tolerability of the product in conditions that are far from the selectivity of the RCTs and closer to real life.

Secondly, the absence of blinding between site colonoscopists and type of bowel preparation performed by patients. This was mainly due to overt differences of treatments, depending on patient characteristics and indication, which did not make a blinding design feasible. In fact, in some centers, colonoscopists are aware that some categories of patients (e.g., inpatients and patients undergoing screening), received only one specific preparation directly provided by the hospital.

Nevertheless, the absence of blinding exposes to additional potential biases, primarily to the observer expectation bias, since the knowledge of the hypotheses can influence the observer to stretch out for the product being tested, compared to the reference standard products.

Finally, the cleansing success rates observed in this study were suboptimal. This may depend on the demographic characteristics of the study population with a relevant proportion of elderly, inpatients and patients with comorbidities, factors that may affect the quality of the bowel preparation.

Concerning the scales used for the assessment of the outcomes, we used the BBPS as it is the most widely validated and the only one that significantly correlates with polyp detection and surveillance intervals[17]. With regards to tolerability, we used a semi-quantitative scale with a score ranging from 1 to 10 by the judgment of the patients, since a validated scale for the assessment of bowel preparation tolerability is not currently available. In the NOCT study only, the Bowel Cleansing Impact Review (BOCLIR) was used[18]. Nevertheless, this is a complex score that features 34 items, and external validation of the score is absent.

In conclusion, results from this study support the effectiveness and tolerability of very low-volume preparation for colonoscopy and also show it is an independent predictor of overall cleansing success, high-quality cleansing of the right colon and of tolerability. In the future, this very-low-volume solution will be useful to improve the quality and tolerability of bowel preparation increasing, at the same time, the adherence to CRC screening and surveillance programs.

The effectiveness of colonoscopy strictly depends on adequate bowel cleansing. Recently, a 1 L polyethylene glycol plus ascorbate (PEG-ASC) solution has been introduced on the evidence of three phase-3 randomized controlled trials.

The 1 L PEG-ASC solution has never been tested in a real-life setting, where patients’ characteristics may differ from those of randomized controlled trials volunteers, and where the incidence of adverse events (AEs) may even be higher.

In this study, we aimed to assess the effectiveness and tolerability of the 1 L preparation compared to 4 L and 2 L-PEG solutions in a real-life setting.

Patients undergoing a screening or diagnostic colonoscopy after a 4, 2 or 1 L PEG preparation, were consecutively enrolled in 5 Italian centers. Bowel cleansing was assessed through the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS). Adherence was defined as consumption of at least 75% of each dose, while tolerability was evaluated through a semi-quantitative scale. Safety was systematically monitored through AEs reporting.

Bowel cleansing by Boston Bowel Preparation Scale was 6.5 ± 1.5 overall and 6.3 ± 1.5, 6.2 ± 1.5, 7.3 ± 1.5 in the subgroups of 4 L, 2 L and 1 L-PEG preparation, respectively. Cleansing success was achieved in 72.4%, 74.1% and 90.1%, while a high-quality cleansing of the right colon in 15.9%, 12.0% and 41.4% for 4 L, 2 L and 1 L-PEG preparation groups, respectively. The 1 L preparation was the most tolerated compared to the 2 and 4 L-PEG solutions in the absence of serious AEs within any of the three groups. Multiple regression models confirmed 1 L PEG-ASC preparation as an independent predictor of overall cleansing success, high-quality cleansing of the right colon and of tolerability.

The effectiveness and tolerability of 1 L PEG-ASC show that it is an independent predictor of overall cleansing success, high-quality cleansing of the right colon and of tolerability

This very-low-volume solution will be useful to improve the quality and tolerability of bowel preparation increasing, and the adherence to colorectal cancer screening and surveillance programs.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Serban ED S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: A E-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Løberg M, Kalager M, Holme Ø, Hoff G, Adami HO, Bretthauer M. Long-term colorectal-cancer mortality after adenoma removal. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:799-807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 213] [Cited by in RCA: 251] [Article Influence: 22.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Baxter NN, Goldwasser MA, Paszat LF, Saskin R, Urbach DR, Rabeneck L. Association of colonoscopy and death from colorectal cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 911] [Cited by in RCA: 918] [Article Influence: 57.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sulz MC, Kröger A, Prakash M, Manser CN, Heinrich H, Misselwitz B. Meta-Analysis of the Effect of Bowel Preparation on Adenoma Detection: Early Adenomas Affected Stronger than Advanced Adenomas. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0154149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Clark BT, Laine L. High-quality Bowel Preparation Is Required for Detection of Sessile Serrated Polyps. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1155-1162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rex DK, Imperiale TF, Latinovich DR, Bratcher LL. Impact of bowel preparation on efficiency and cost of colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1696-1700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 395] [Cited by in RCA: 471] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Froehlich F, Wietlisbach V, Gonvers JJ, Burnand B, Vader JP. Impact of colonic cleansing on quality and diagnostic yield of colonoscopy: the European Panel of Appropriateness of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy European multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:378-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 642] [Cited by in RCA: 698] [Article Influence: 34.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wexner SD, Beck DE, Baron TH, Fanelli RD, Hyman N, Shen B, Wasco KE; American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons; American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy; Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons. A consensus document on bowel preparation before colonoscopy: prepared by a task force from the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS), the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES). Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:894-909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hillyer GC, Basch CH, Lebwohl B, Basch CE, Kastrinos F, Insel BJ, Neugut AI. Shortened surveillance intervals following suboptimal bowel preparation for colonoscopy: results of a national survey. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28:73-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hassan C, East J, Radaelli F, Spada C, Benamouzig R, Bisschops R, Bretthauer M, Dekker E, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Ferlitsch M, Fuccio L, Awadie H, Gralnek I, Jover R, Kaminski MF, Pellisé M, Triantafyllou K, Vanella G, Mangas-Sanjuan C, Frazzoni L, Van Hooft JE, Dumonceau JM. Bowel preparation for colonoscopy: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline - Update 2019. Endoscopy. 2019;51:775-794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 407] [Cited by in RCA: 347] [Article Influence: 57.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 10. | Johnson DA, Barkun AN, Cohen LB, Dominitz JA, Kaltenbach T, Martel M, Robertson DJ, Boland CR, Giardello FM, Lieberman DA, Levin TR, Rex DK; US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Optimizing adequacy of bowel cleansing for colonoscopy: recommendations from the US multi-society task force on colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:903-924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 305] [Cited by in RCA: 299] [Article Influence: 27.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Radaelli F, Meucci G, Sgroi G, Minoli G; Italian Association of Hospital Gastroenterologists (AIGO). Technical performance of colonoscopy: the key role of sedation/analgesia and other quality indicators. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1122-1130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lee TJ, Rutter MD, Blanks RG, Moss SM, Goddard AF, Chilton A, Nickerson C, McNally RJ, Patnick J, Rees CJ. Colonoscopy quality measures: experience from the NHS Bowel Cancer Screening Programme. Gut. 2012;61:1050-1057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 249] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Halphen M, Tayo B, Flanagan S, Clayton LB, Kornberger R. Pharmacodynamic and clinical evaluation of low-volume polyethylene glycol (PEG)-based bowel cleansing solutions (NER1006) using split dosing in healthy and screening colonoscopy subjects. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:S189. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | DeMicco MP, Clayton LB, Pilot J, Epstein MS; NOCT Study Group. Novel 1 L polyethylene glycol-based bowel preparation NER1006 for overall and right-sided colon cleansing: a randomized controlled phase 3 trial versus trisulfate. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87:677-687.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Schreiber S, Baumgart DC, Drenth JPH, Filip RS, Clayton LB, Hylands K, Repici A, Hassan C; DAYB Study Group. Colon cleansing efficacy and safety with 1 L NER1006 versus sodium picosulfate with magnesium citrate: a randomized phase 3 trial. Endoscopy. 2019;51:73-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bisschops R, Manning J, Clayton LB, Ng Kwet Shing R, Álvarez-González M; MORA Study Group. Colon cleansing efficacy and safety with 1 L NER1006 versus 2 L polyethylene glycol + ascorbate: a randomized phase 3 trial. Endoscopy. 2019;51:60-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kahi CJ, Vemulapalli KC, Johnson CS, Rex DK. Improving measurement of the adenoma detection rate and adenoma per colonoscopy quality metric: the Indiana University experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:448-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Doward L, Wilburn J, McKenna SP, Leicester R, Epstein O, Hedley V, Korala S, Twiss J, Jones D, Geraint M. Development and validation of the Bowel Cleansing Impact Review (BOCLIR). Frontline Gastroenterol. 2013;4:112-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |