Published online Apr 7, 2020. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i13.1525

Peer-review started: December 9, 2019

First decision: December 30, 2019

Revised: January 9, 2020

Accepted: March 9, 2020

Article in press: March 9, 2020

Published online: April 7, 2020

Processing time: 120 Days and 0.8 Hours

Nucleos(t)ide analog (NA) has shown limited effectiveness against hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) clearance in chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients.

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of add-on peginterferon α-2a (peg-IFN α-2a) to an ongoing NA regimen in CHB patients.

In this observational study, 195 CHB patients with HBsAg ≤ 1500 IU/mL, hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)-negative (including HBeAg-negative patients or HBeAg-positive patients who achieved HBeAg-negative after antiviral treatment with NA) and hepatitis B virus-deoxyribonucleic acid < 1.0 × 102 IU/mL after over 1 year of NA therapy were enrolled between November 2015 and December 2018 at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University, China. Patients were given the choice between receiving either peg-IFN α-2a add-on therapy to an ongoing NA regimen (add-on group, n = 91) or continuous NA monotherapy (monotherapy group, n = 104) after being informed of the benefits and risks of the peg-IFN α-2a therapy. Total therapy duration of peg-IFN α-2a was 48 wk. All patients were followed-up to week 72 (24 wk after discontinuation of peg-IFN α-2a). The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients with HBsAg clearance at week 72.

Demographic and baseline characteristics were comparable between the two groups. Intention-to-treatment analysis showed that the HBsAg clearance rate in the add-on group and monotherapy group was 37.4% (34/91) and 1.9% (2/104) at week 72, respectively. The HBsAg seroconversion rate in the add-on group was 29.7% (27/91) at week 72, and no patient in the monotherapy group achieved HBsAg seroconversion at week 72. The HBsAg clearance and seroconversion rates in the add-on group were significantly higher than in the monotherapy group at week 72 (P < 0.001). Younger patients, lower baseline HBsAg concentration, lower HBsAg concentrations at weeks 12 and 24, greater HBsAg decline from baseline to weeks 12 and 24 and the alanine aminotransferase ≥ 2 × upper limit of normal during the first 12 wk of therapy were strong predictors of HBsAg clearance in patients with peg-IFN α-2a add-on treatment. Regarding the safety of the treatment, 4.4% (4/91) of patients in the add-on group discontinued peg-IFN α-2a due to adverse events. No severe adverse events were noted.

Peg-IFN α-2a as an add-on therapy augments HBsAg clearance in HBeAg-negative CHB patients with HBsAg ≤ 1500 IU/mL after over 1 year of NA therapy.

Core tip: Despite promising results with the combination therapy of Peg-interferon and nucleos(t)ide analog (NA), the best combination therapeutic strategy of Peg-interferon and NA to the treatment of chronic hepatitis B remains unclear. This prospective study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of adding 48 wk of peginterferon α-2a treatment to an ongoing NA regime in chronic hepatitis B patients with hepatitis B surface antigen levels ≤ 1500 IU/mL, hepatitis B e antigen-negative and hepatitis B virus-deoxyribonucleic acid < 1.0 × 102 IU/mL after over 1 year of NA therapy.

- Citation: Wu FP, Yang Y, Li M, Liu YX, Li YP, Wang WJ, Shi JJ, Zhang X, Jia XL, Dang SS. Add-on pegylated interferon augments hepatitis B surface antigen clearance vs continuous nucleos(t)ide analog monotherapy in Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B and hepatitis B surface antigen ≤ 1500 IU/mL: An observational study. World J Gastroenterol 2020; 26(13): 1525-1539

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v26/i13/1525.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v26.i13.1525

Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection remains a major public health challenge. Approximately 2 billion persons are infected by HBV globally. Up to 240 million persons are chronic HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) carriers, and they contribute to approximately 30% of liver cirrhosis cases and 45% of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cases in the world[1]. Antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients is a key strategy to prevent the progression of CHB.

Currently, the approved therapeutic options for CHB patients include nucleos(t)ide analog (NA) and peginterferon alfa (peg-IFN α). Antiviral therapy may achieve HBsAg clearance or seroconversion in a small percentage of CHB patients. It is reported that the rate of HBsAg clearance is less than 5% after 5 years of entecavir (ETV) therapy[2] and less than 7% after 1 year of peg-IFN α monotherapy[3,4]. Although the rate of HBsAg clearance is very low, it demonstrated that CHB is a disease that can be ‘cured’ through effective treatment, which may not completely clear HBV, but close to the status of complete eradication of HBV, including covalently closed circular deoxyribonucleic acid[5].

The Guideline of Prevention and Treatment for Chronic Hepatitis B (2015 Update, China) firstly proposed a concept of “clinical cure” or “functional cure,” which is the optimal therapeutic endpoint of CHB and the ultimate indicator of immune control of HBV infection[6-9]. Meanwhile, the 2015 updated Asian-Pacific clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatitis B affirmed the “clinical cure” of CHB[10]. Therefore, new therapeutic strategies for boosting HBsAg clearance in CHB patients are required. Several studies have investigated new treatment strategies involving various combined approaches with NA and peg-IFN α and reported encouraging HBsAg clearance rates from 8.5% to 33.3%[11-13]. The findings from these studies and some uncontrolled small studies also showed that peg-IFN α-based treatment was associated with a higher rate of HBsAg clearance in patients with low baseline levels of HBsAg and HBV DNA[14,15]. Moreover, the interim analysis of NEW SWITCH study and another small study all showed that patients with lower HBsAg level at baseline (< 1500 IU/mL) achieved a higher HBsAg clearance rate than patients with HBsAg > 1500 IU/mL when they switched from NA to 48 wk of peg-IFN α-2α therapy[16,17].

Preliminary statistical analysis in our center indicates that 75.5% (3677/4870) of CHB patients received NA treatment, including lamivudine, adefovir dipivoxil (ADV), telbivudine, ETV, and tenofovir fumarate (TDF). In those patients with NA treatment, 37.7% (1386/3677) of patients were hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)-negative and HBsAg ≤ 1500 IU/mL after over 1 year of NA treatment (unpublished data). Based on these data, we estimate that approximately 5.69-8.53 million CHB patients in China are HBsAg ≤ 1500 IU/mL after over 1 year of NA treatment. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of add-on peg-IFN α-2a in CHB patients who are receiving long-term NA treatment with HBsAg levels less and equal to 1500 IU/mL. In addition, logistic regression analysis was used to analyze independent prediction factors of HBsAg clearance in this population.

This study was conducted at the Department of Infectious Diseases of the Second Affiliated Hospital, Xi’an Jiaotong University, Xi’an, China between November 2015 and December 2018. The study complies with good clinical practice and the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Xi'an Jiaotong University. All patients provided written consent before enrollment in the study. Inclusion criteria included: (1) Age between 18- and 65-years-old; (2) HBsAg positive for at least 6 mo prior to enrollment; (3) Serum HBsAg ≤ 1500 IU/mL, HBeAg-negative (including HBeAg-negative patients or HBeAg-positive patients who achieved HBeAg-negative after antiviral treatment with NA) and HBV DNA < 1.0 × 102 IU/mL after at least 1 year of NA therapy, including lamivudine, ADV, telbivudine, ETV, and TDF; (4) Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) concentration less than five times of the upper limit of normal (ULN) level (because of the risk of hepatic flare with interferon-based therapy); (5) White blood cell counts in a range of 4-10 × 109 /L, or platelet (PLT) counts in a range of 100-300 × 109/L; (6) No cirrhosis and splenomegaly in abdominal computed tomography; and (7) Naïve to interferon treatment. Exclusion criteria included: (1) Co-infected with hepatitis A, C, D, or human immunodeficiency virus; (2) Decompensated liver diseases, alcohol or drug abuse, autoimmune diseases, severe metabolic diseases, HCC or tumors of any systems; (3) Severe complications in any organ; and (4) Pregnant or lactating women.

This study was a single center, prospective, observational study. After being informed of the benefits and risks of the peg-IFN α-2a therapy, patients were given the choice between receiving either 180 μg of peg-IFN α-2a (Pegasys; Roche, Shanghai, China) add-on therapy once weekly to an ongoing NA regimen (add-on group) or continuous NA monotherapy (monotherapy group). The dosage of peg-IFN α-2a was adjusted to 135 μg/wk if the neutrophil counts were ≤ 0.75 × 109/L or PLT < 50 × 109/L. Peg-IFN α-2a was discontinued if the neutrophil counts were ≤ 0.50 × 109/L, PLT < 25 × 109/L or serious adverse events (AEs) occurred. The total duration of peg-IFN α-2a add-on therapy was 48 wk. All groups were followed up to week 72 (24 wk after discontinuation of peg-IFN α-2a). Patients discontinued the NA therapy if HBsAg was negative at week 72. The primary endpoint was HBsAg clearance at week 72 and the secondary endpoints included the rate of HBsAg clearance at week 48, the rates of HBsAg seroconversion at weeks 48 and 72, HBsAg, ALT and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) dynamics over time and the safety during treatment.

Study assessments were based on the laboratory results, clinical and safety evaluations. Laboratory results including white blood cell, PLT, ALT, AST, HBV DNA, HBsAg and anti-HBs antibody in serum samples were measured at baseline, weeks 4, 8, 12, 24, 36, 48 and 72 in all patients. Thyroid hormone, thyroid antibodies, and autoantibodies were tested at baseline and every 12 wk during treatment. Study assessments were described in the Supplementary Table 1. HBsAg and anti-HBs antibody were quantified using the commercially available reagent kits (Architect assay; Abbott Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The limit of detection for HBsAg was 0.05 IU/mL. Serum HBV DNA was detected using the TaqMan based real-time polymerase chain reaction assay (Shanghai ZJ BioTech, Shanghai, China) with the limit of detection of 100 IU/mL. HBsAg titer < 0.05 IU/mL indicated the loss of HBsAg; anti-HBs antibody level > 10 mIU/mL was defined as positive. Serum ALT was assayed by an automatic biochemical analyzer (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and presented as multiples of the ULN (men: 50 IU/L; women: 40 IU/L). Clinical evaluation included family history of HBV, prior NA history, body mass index (BMI) and liver stiffness. Liver stiffness measurement was performed by transient elastography (FibroScan, EchoSens, Paris, France). All patients were asked about the family history of CHB. Patients with clear family history of CHB were considered as HBV vertical transmission. Those who declined to provide the family history of CHB were grouped as others. Safety assessment included headache, alopecia and pyrexia.

| Characteristics | Add-on, n = 91 | Monotherapy, n = 104 | P value |

| Male (%) | 62 (68.1) | 76 (73.1) | 0.528 |

| Age in yr, mean ± SD | 38.11 ± 9.74 | 37.34 ± 11.01 | 0.529 |

| BMI in kg/cm2, mean ± SD | 21.97 ± 1.72 | 22.13 ± 1.05 | 0.157 |

| Mode of transmission | |||

| Vertical (%) | 36 (39.6) | 32 (30.8) | 0.229 |

| Others (%) | 55 (60.4) | 72 (69.2) | |

| HBsAg at week 0 | |||

| < 500 IU/mL (%) | 56 (61.5) | 49 (47.1) | 0.089 |

| 500-1000 IU/mL (%) | 17 (18.7) | 32 (30.8) | |

| 1000-1500 IU/mL (%) | 18 (19.8) | 23 (22.1) | |

| HBeAg status at enrollment | |||

| Negative (%) | 91 (100) | 104 (100) | _ |

| HBV DNA at enrollment | |||

| < 1.0 × 102 IU/ mL (%) | 91 (100.0) | 104 (100.0) | _ |

| ALT, IU/L, median (range) | 24 (8.0-73) | 27 (7-66) | 0.558 |

| AST, IU/L, median (range) | 23 (12-70) | 26 (14-66) | 0.212 |

| NA | |||

| ADV (%) | 10 (11.0) | 12 (11.5) | 0.395 |

| ETV (%) | 50 (54.9) | 66 (63.5) | |

| TDF (%) | 31 (34.1) | 26 (25.0) | |

| FibroScan value, kPa | |||

| mean ± SD | 4.2 ± 1.1 | 4.5 ± 1.2 | 0.824 |

All patients enrolled in this study were included in the final efficacy analysis. All available AE data up to week 72 were included in the safety analysis for characterizing the full safety profile within the study. The analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 13.0, Chicago, IL, United States). Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median (range) for continuous variables as appropriate. Student’s t or Mann-Whitney U test or analysis of variance for repeated measures design data was used for intergroup comparison of continuous variables as appropriate. Categorical variables were analyzed as counts and percentages and compared using χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. The proportion of patients with HBsAg clearance and HBsAg seroconversion at weeks 48 and 72 was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Data for patients without HBsAg clearance were censored at the last time point. Comparisons between groups were conducted using the log-rank test. ROC curves were applied to evaluate the parameters for predicting HBsAg clearance. Cut-off values were identified by maximizing the sum of sensitivity and specificity, and the nearest clinically applicable value to cut-off was considered optimal for clinical convenience. Univariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to evaluate the magnitude and significance of independent variables associated with the dependent variable. All statistical tests were two-sided and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

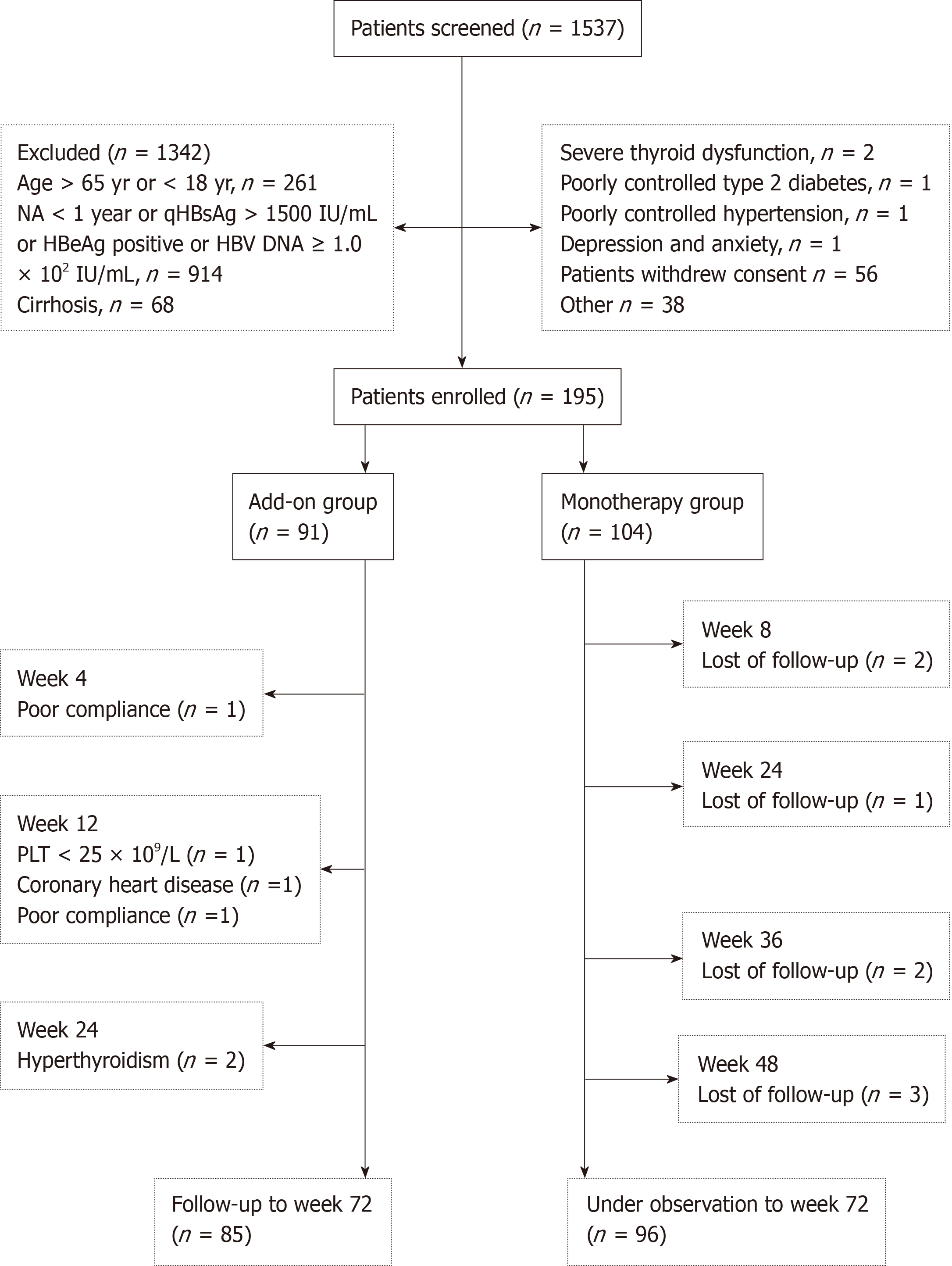

The flow chart of patient enrollment in this study is shown in Figure 1. Of the 1537 patients screened, 195 patients were enrolled, 91 (46.7%) of whom received peg-IFN α-2a add-on therapy as the add-on group and 104 (53.3%) of whom continued NA monotherapy as the monotherapy group. Patient demographic and baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. The two groups were comparable in terms of the demographic and baseline characteristics.

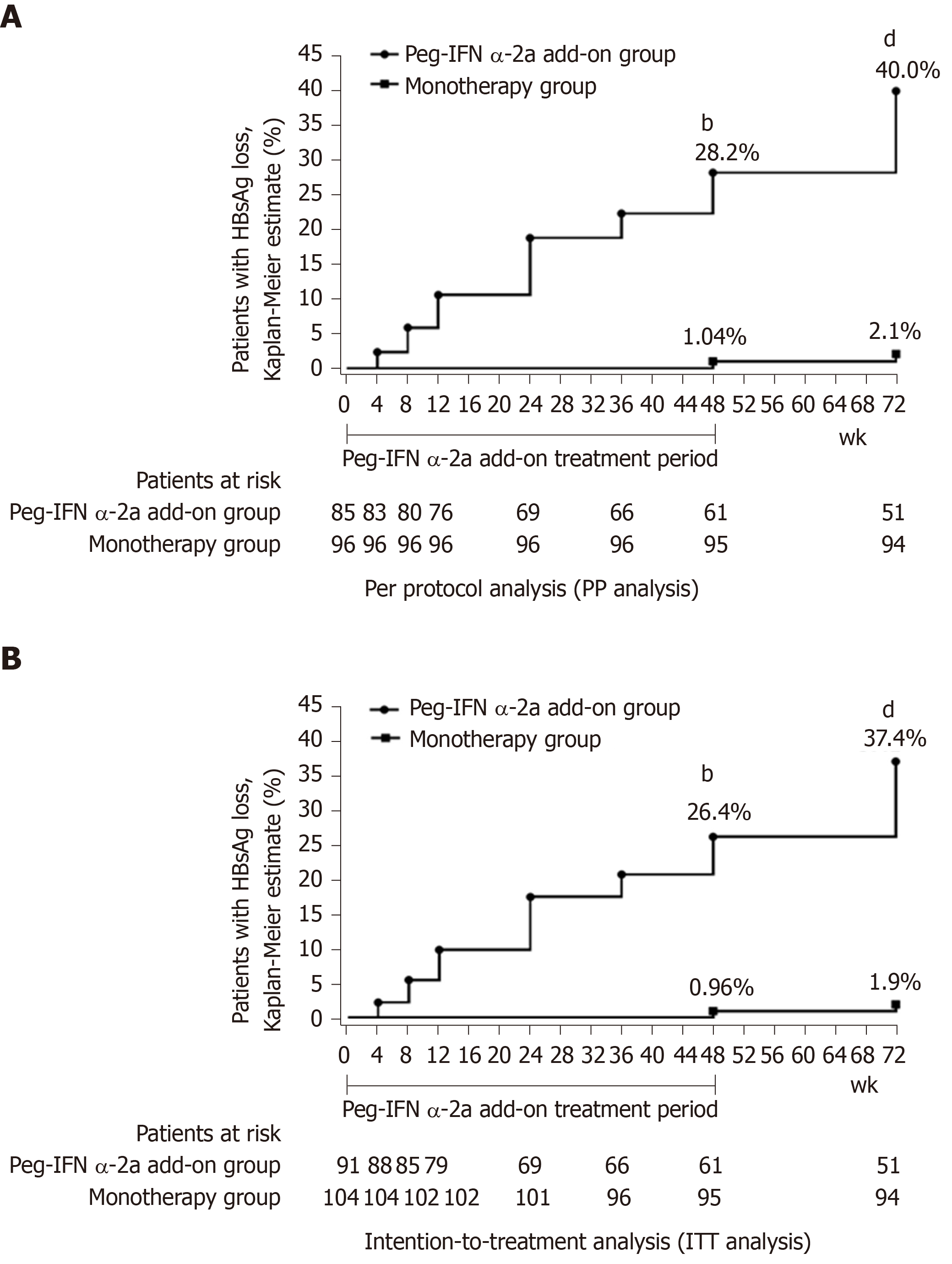

At week 72, per protocol analysis (PP analysis) showed that 40.0% (34/85) of patients in the add-on group had HBsAg clearance compared with 2.1% (2/96) of patients in the monotherapy group. The HBsAg clearance rate in the add-on group was significantly higher than in the monotherapy group at week 72 (Figure 2A) (P < 0.001). Furthermore, we also did an intention-to-treatment analysis (ITT analysis), and the results showed that the HBsAg clearance rate was 37.4% (34/91) in the add-on group and 1.9% (2/104) in the monotherapy group at week 72. Similar to the PP analysis, the HBsAg clearance rate in the add-on group was significantly higher than that in the monotherapy group at week 72 (Figure 2B) (P < 0.001).

HBsAg clearance rate at week 48: PP analysis showed that the HBsAg clearance rate in the add-on group was 28.2% (24/85) at week 48, significantly higher than 1.04% (1/96) in the monotherapy group (Figure 2A) (P < 0.001). ITT analysis also showed the HBsAg clearance rate was significantly higher in the add-on group than in the monotherapy group [26.4% (24/91) vs 0.96% (1/104), P < 0.001] (Figure 2B).

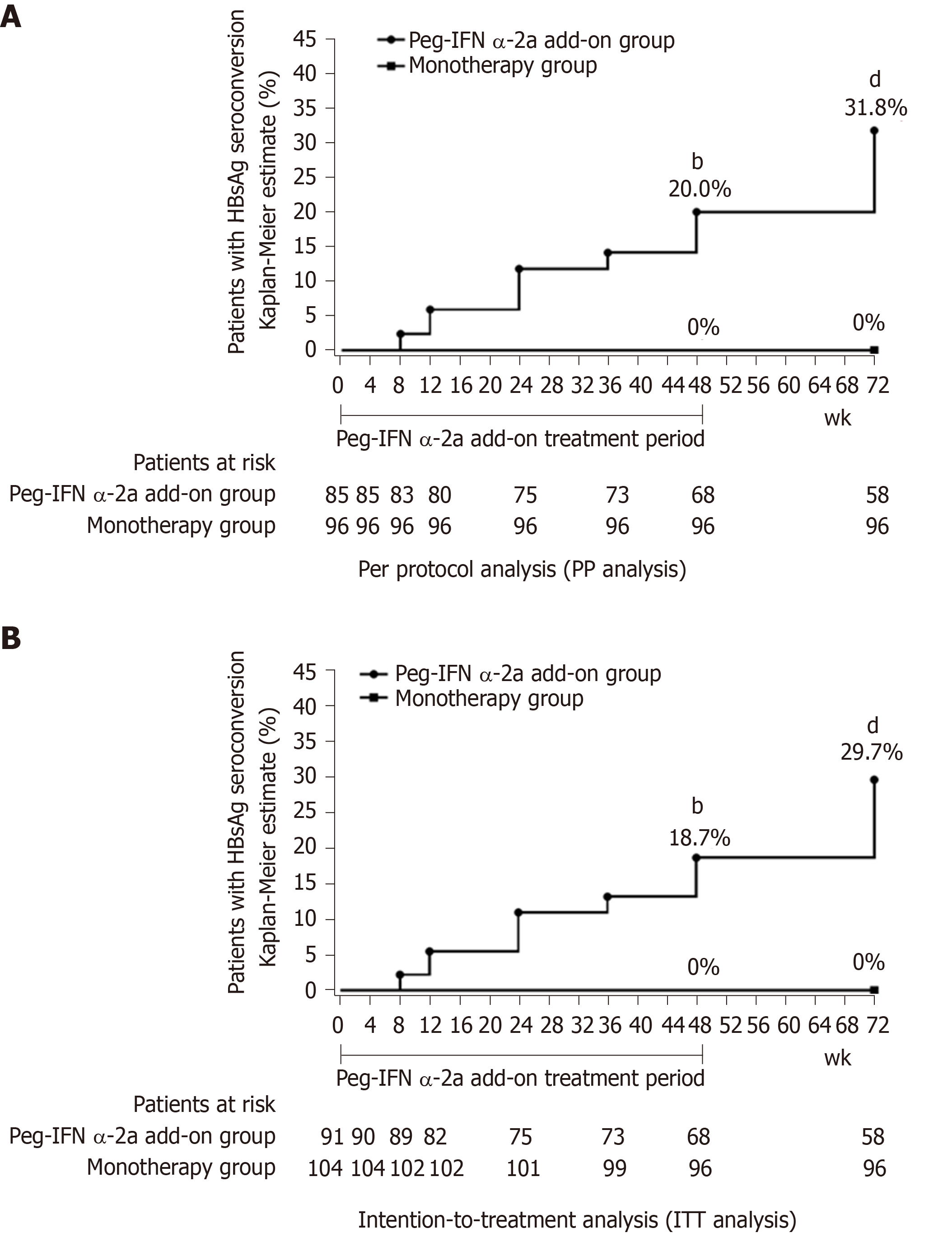

HBsAg seroconversion rates: PP analysis showed that the HBsAg seroconversion rate in the peg-IFN α-2a add-on group was 20.0% (17/85) at week 48 and 31.8% (27/85) at week 72. No patient in the monotherapy group achieved HBsAg seroconversion. The HBsAg seroconversion rate in the add-on group was significantly higher than those in the monotherapy group at weeks 48 and 72 (Figure 3A) (P < 0.001 for all). ITT analysis showed that the HBsAg seroconversion rate in the peg-IFN α-2a add-on group was 18.7% (17/91) at week 48 and 29.7% (27/91) at week 72. Consistent to the PP analysis, ITT analysis also showed the HBsAg seroconversion rate in the add-on group was significantly higher than those in the monotherapy group at weeks 48 and 72 (Figure 3B) (P < 0.001 for all).

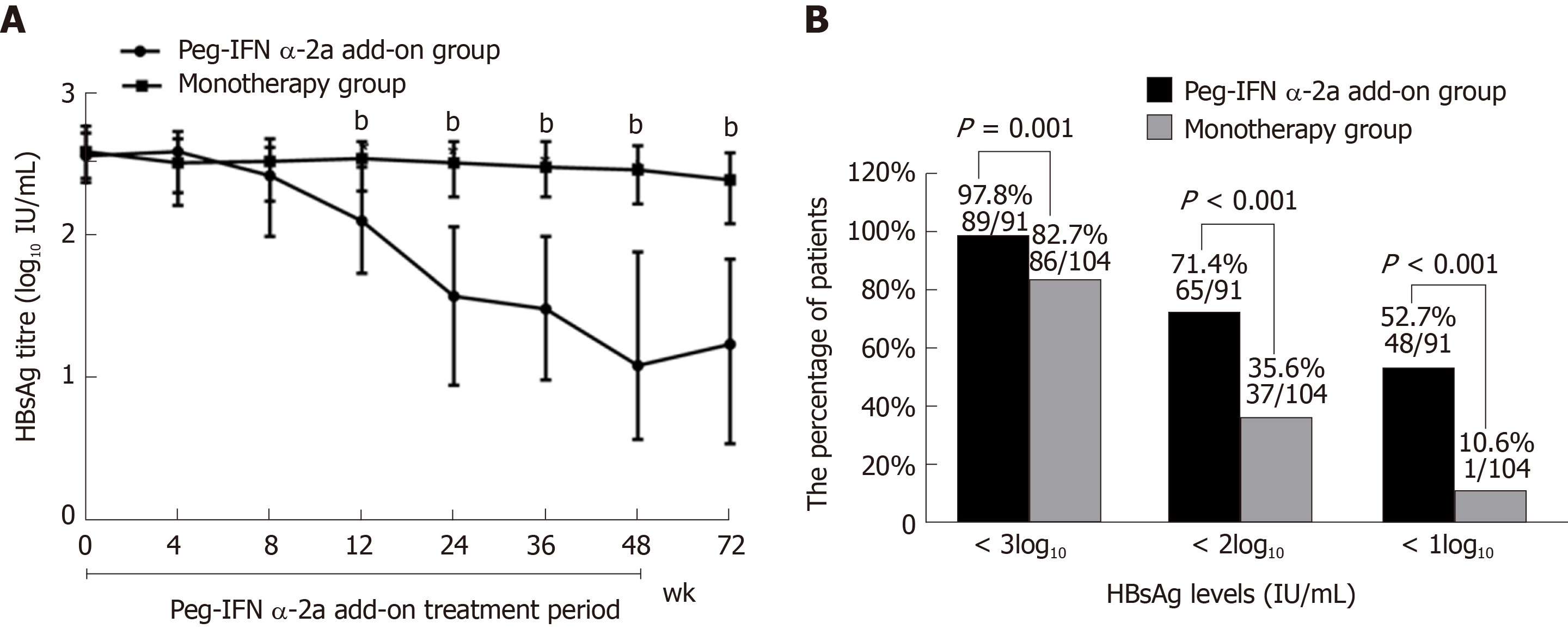

HBsAg dynamics: In the peg-IFN α-2a add-on group, median serum HBsAg level declined from 2.56 log10 IU/mL at baseline to 1.08 log10 IU/mL after 48 wk of the treatment and to 1.23 log10 IU/mL at 72 wk. In the monotherapy group, median serum HBsAg level declined from 2.59 log10 IU/mL at baseline to 2.46 log10 IU/mL at 48 wk to 2.40 log10 IU/mL at 72 wk. Patients in the peg-IFN α-2a add-on group showed significantly lower median serum HBsAg levels at weeks 12, 24, 36, 48 and 72 than patients in the monotherapy group (P < 0.001 for all comparisons) (Figure 4A).

Interestingly, HBsAg elevations were observed at 4 wk after adding on peg-IFN α-2a in 57.1% (52/91) of patients in the peg-IFN α-2a add-on group, and HBsAg gradually decreased 4 wk later. Median serum HBsAg level increased from 2.77 log10 IU/mL at baseline to 2.87 log10 IU/mL after 4 wk of peg-IFN α-2a add-on therapy, gradually decreased to 2.76 log10 IU/mL at week 8, to 1.99 log10 IU/mL at week 48 and to 1.81 log10 IU/mL at week 72.

The HBsAg clearance rate of these 52 patients was 28.8% (15/52) at week 72, which was comparable with patients whose HBsAg decreased at four weeks after adding on peg-IFN α-2a [48.7% (19/39)] (P = 0.079), demonstrating that HBsAg elevations at 4 wk after adding on peg-IFN α-2a therapy had no influence on treatment outcome.

Furthermore, more patients in the add-on group had low levels of HBsAg at the end of follow-up than the monotherapy group. Most patients (97.8%, 89/91) in the add-on group demonstrated HBsAg levels < 3log10 IU/mL (vs monotherapy group 82.7%, 86/104; P = 0.001). Moreover, 71.4% (65/91) of patients in the add-on group showed HBsAg levels < 2log10 IU/mL (vs monotherapy group 35.6%, 37/104; P < 0.001). Meanwhile, 52.7% (48/91) of patients in the add-on group showed HBsAg levels < 1log10 IU/mL (vs monotherapy group 10.6%, 11/104; P < 0.001) (Figure 4B).

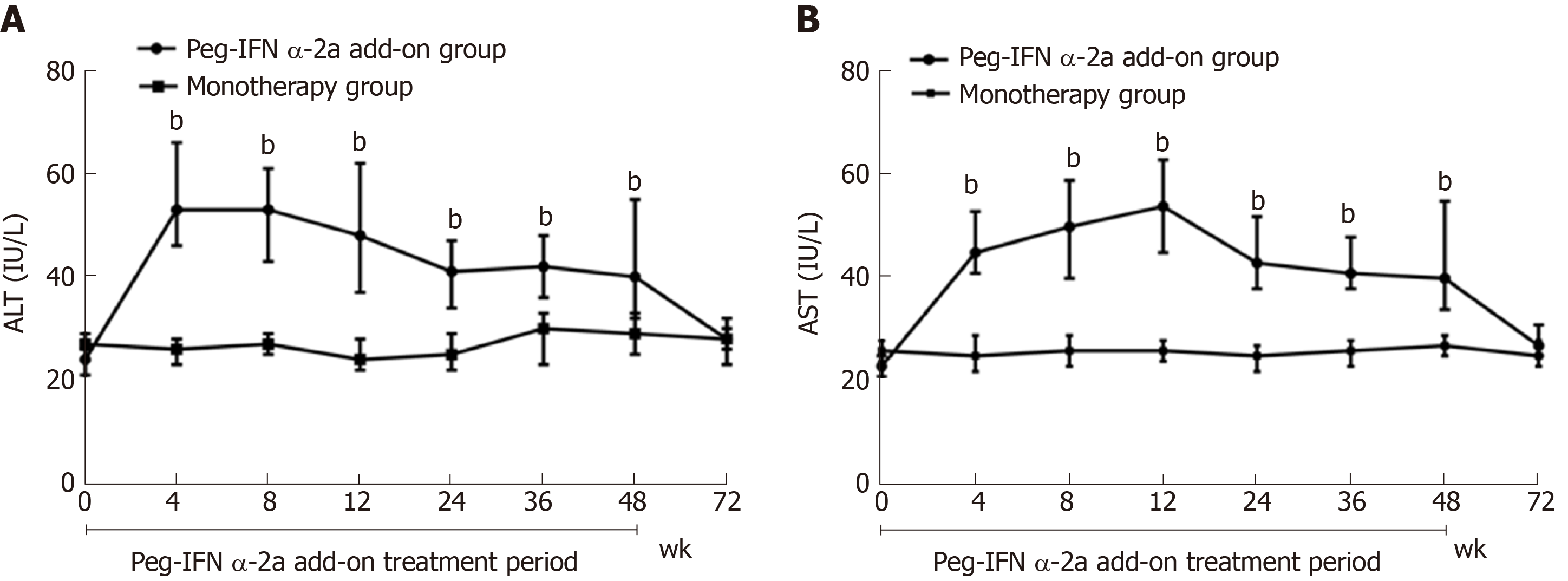

ALT and AST dynamics: ALT and AST elevations were observed early (at 4 wk) after adding on peg-IFN α-2a in patients in the peg-IFN α-2a add-on group. Patients in peg-IFN α-2a add-on group had significantly higher serum ALT and AST levels at weeks 4, 8, 12, 24, 36 and 48 than patients in the monotherapy group (P < 0.001 for all time points). After discontinuation of peg-IFN α-2a at week 48, ALT and AST gradually returned to normal levels at week 72 (vs monotherapy group, P = 0.52 for ALT; P = 0.099 for AST (Figure 5A and 5B).

Almost half [46.2% (42/91)] of the patients in the peg-IFN α-2a add-on group showed ALT ≥ 2 × ULN during the first 12 wk of therapy with a maximum of 414 IU/L. To evaluate the ALT change on HBsAg clearance, we dichotomized the patients into two groups (ALT ≥ 2 × ULN or < 2 × ULN) at week 12, and two groups of patients followed the same treatment. To evaluate the baseline characteristics [gender, age (years), baseline HBsAg level (in log10 scale, IU/mL), ALT (IU/L), mode of HBV transmission, body mass index (kg/cm2), FibroScan value (kPa), NA (nucleoside analogue or nucleotide analog)] and on-treatment factors [HBsAg levels (log10 IU/mL) at weeks 12 and 24, HBsAg decline at weeks 12 and 24 versus baseline, and increase of ALT ≥ 2 × ULN during the first 12 wk of therapy] in predicting HBsAg clearance at week 72, univariable logistic regression analysis was performed. The results showed that age [P = 0.002, OR = 0.924; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.878-0.972], baseline HBsAg level (P = 0.003, OR = 0.371; 95%CI: 0.194-0.711), HBsAg level at week 12 (P < 0.001, OR = 0.273, 95%CI: 0.157-0.474), HBsAg level at week 24 (P < 0.001, OR = 0.218, 95%CI: 0.117-0.405), HBsAg decline from baseline to week 12 (P < 0.001, OR = 10.646, 95%CI: 3.776-25.018), HBsAg decline from baseline to week 24 (P < 0.001, OR = 7.045, 95%CI: 3.223-15.400) and ALT elevation ≥ 2 × ULN during the first 12 wk of therapy (P = 0.002, OR = 4.182, 95%CI: 1.691-10.340) were strong predictors for HBsAg clearance at week 72. Baseline gender, ALT, mode of HBV transmission, body mass index, FibroScan value and NA (nucleoside analogue or nucleotide analog) were not statistically significant (Table 2).

| Predictors | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

| OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Gender | 2.045 | (0.792-5.283) | 0.149 | - | - | - |

| ALT in IU/L | 0.997 | (0.968-1.027) | 0.852 | - | - | - |

| FibroScan value in kPa | 0.794 | (0.549-1.125) | 0.803 | - | - | - |

| BMI in kg/cm2 | 0.962 | (0.951-1.218) | 0.794 | - | - | - |

| NA | 1.790 | (0.758-4.225) | 0.184 | - | - | - |

| Mode of HBV transmission | 0.840 | (0.298-2.372) | 0.742 | - | - | - |

| Age, yr | 0.924 | (0.878-0.972) | 0.002 | 0.946 | (0.833-0.981) | 0.025 |

| Baseline HBsAg as log10 IU/mL | 0.371 | (0.194-0.711) | 0.003 | 0.557 | (0.206-0.827) | 0.019 |

| Week 12 HBsAg as log10 IU/mL | 0.273 | (0.157-0.474) | < 0.001 | 0.542 | (0.194-0.792) | 0.002 |

| Week 24 HBsAg as log10 IU/mL | 0.218 | (0.117-0.405) | < 0.001 | 0.188 | (0.058-0.410) | 0.004 |

| HBsAg decline as log10 IU/mL | ||||||

| From baseline to week 12 | 10.646 | (3.776-25.018) | < 0.001 | 8.925 | (3.376-17.226) | < 0.001 |

| From baseline to week 24 | 7.045 | (3.223-15.400) | < 0.001 | 8.830 | (4.553-18.213) | < 0.001 |

| ALT ≥ 2 × ULN in the first 12 wkF1 | 4.182 | (1.691-10.340) | 0.002 | 5.275 | (3.324-11.823) | 0.014 |

In order to further evaluate age, baseline and decline of HBsAg in early treatment and ALT elevation in early treatment in predicting HBsAg clearance at week 72, multivariable logistic regressions were conducted for age, HBsAg levels at baseline, week 12, and week 24 as well as the week 12 and week 24 HBsAg decline from baseline adjusted for gender and NA. Similar to the univariable regression analysis results, all variables were significantly related to HBsAg clearance at week 72: age (P = 0.025, OR = 0.946; 95%CI: 0.833-0.981), baseline HBsAg level (P = 0.019, OR = 0.557; 95%CI: 0.206-0.827), HBsAg level at week 12 (P = 0.002, OR = 0.542, 95%CI: 0.194-0.792), HBsAg level at week 24 (P = 0.004, OR = 0.188, 95%CI: 0.058-0.410), HBsAg decline from baseline to week 12 (P < 0.001, OR = 8.925, 95%CI: 3.376-17.226), HBsAg decline from baseline to week 24 (P < 0.001, OR = 8.830, 95%CI: 4.553-18.213) and ALT elevation ≥ 2 × ULN during the first 12 wk of therapy (P = 0.014, OR = 5.275, 95%CI: 3.324-11.823) (Table 2).

Rates of HBsAg clearance among patients with favorable baseline, week 12, week 24 antiviral treatment response: ROC curves were used to evaluate the performance of the above significant variables for HBsAg clearance. The AUROC of age was 0.699, and the optimal cut-off point was 33 years. The AUROCs of HBsAg level were 0.689, 0.877, 0.921, and the optimal cut-off points were 2.25 log10 IU/mL for baseline, 1.89 log10 IU/mL for week 12 and 1.46 log10 IU/mL for week 24. The AUROCs of HBsAg decline from baseline to week 12 and week 24 were 0.901 and 0.924, respectively, and the optimal cut-off points were 0.5 log10 IU/mL and 1.0 log10 IU/mL, respectively (Table 3).

| Factors | Area | SD | 95%CI | Cut-off point | Sensitivityand specificity | HBsAg clearance rate |

| Age in yr | 0.699 | 0.056 | (0.589-0.809) | 33 | 55.9%, 77.2% | 58.1% (18/31) |

| Baseline HBsAg as log10 IU/mL | 0.689 | 0.059 | (0.573-0.806) | 2.25 | 52.9%, 80.7% | 62.1% (18/29) |

| Week 12 HBsAg as log10 IU/mL | 0.877 | 0.04 | (0.803-0.951) | 1.89 | 85.3%, 82.5% | 73.7% (28/38) |

| Week 24 HBsAg as log10 IU/mL | 0.921 | 0.03 | (0.861-0.980) | 1.46 | 94.1%, 78.9% | 72.7% (32/44) |

| HBsAg decline as log10 IU/mL | ||||||

| From baseline to week 12 | 0.901 | 0.032 | (0.839-0.963) | 0.5 | 85.3%, 88.7% | 80.0% (28/35) |

| From baseline to week 24 | 0.924 | 0.031 | (0.864-0.985) | 1.0 | 91.2%, 86.0% | 77.5% (31/40) |

Based on the optimal cut-off values, our data showed that the rates of HBsAg clearance were 58.1% (18/31) for patients younger than 33-years-old and 62.1% (18/29) for patients with baseline HBsAg < 2.25 log10 IU/mL. Patients with HBsAg < 1.89 log10 IU/mL at week 12 had an HBsAg clearance rate of 73.7% (28/38). Patients with HBsAg < 1.46 log10 IU/mL at week 24 had an HBsAg clearance rete of 72.7% (32/44). The rates of HBsAg clearance were 80.0% (28/35) and 77.5% (31/40) for patients with HBsAg decline > 0.5 log10 IU/mL from baseline to week 12 and > 1.0 log10 IU/mL to week 24. Patients with ALT ≥ 2 × ULN during the first 12 wk of therapy demonstrated 54.8% (23/42) of HBsAg clearance (Table 3).

AEs were analyzed in the study population up to 72 wk. Many (90.1%) of the patients in the add-on group experienced AEs, which was significantly higher than 9.6% in the NA alone group (Table 4). The most common AEs were thrombocytopenia (90.1%), followed by neutropenia (87.9%) and pyrexia (82.4%) in the add-on group. Due to AEs, 4.4% (4/91) of patients in the add-on group discontinued peg-IFN α-2a, including two patients who suffered from hyperthyroidism at week 24, one patient with thrombocytopenia (25 × 109/L) and one with coronary heart disease deterioration at week 12. ALT flares (> 5 × ULN) occurred in 7.7% of the add-on group. No patient in the monotherapy group discontinued treatment due to safety reasons.

| AEs | Add-on, n = 91 | Monotherapy, n = 104 | P value |

| Neutropenia | 80 (87.9) | 8 (7.7) | < 0.001 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 82 (90.1) | 9 (8.7) | < 0.001 |

| Fever | 75 (82.4) | 0 (0) | < 0.001 |

| Fatigue | 53 (58.2) | 10 (9.6) | < 0.001 |

| Anorexia | 49 (53.8) | 3 (2.9) | < 0.001 |

| Weight loss | 15 (16.5) | 0 (0) | < 0.001 |

| Alopecia | 10 (11.0) | 0 (0) | < 0.001 |

| Thyroid dysfunction | 6 (6.6) | 0 (0) | 0.009 |

| ALT flares | 7 (7.7) | 0 (0) | 0.004 |

| Rash | 5 (5.5) | 0 (0) | 0.021 |

| HCC | 0 (0) | 1 (1.0) | 1.000 |

| Virological breakthrough | 0 (0) | 2 (1.9) | 0.500 |

It should be noted that one patient in the monotherapy group developed HCC. Two patients treated with ADV in the monotherapy group experienced virological breakthrough (for patient adherent with NA therapy, serum HBV DNA converted to positivity following sustained negativity and as confirmed 1 mo later using the same regent) and were rescued by TDF and ETV therapy. Considering the risk of virological breakthrough with ADV monotherapy, ADV was replaced by TDF in patients with HBsAg positive at week 72.

NA has been shown to partly restore adaptive immunity, whereas peg-IFN α boosts innate immunity, triggers T-cell-mediated immune responses, prevents formation of HBV proteins and depletes the covalently closed circular DNA pool, which leads to more HBsAg clearance than with NA[18]. Although promising results with the combination use of peg-IFN α and NA were reported from previous studies, the best treatment approach for CHB is still debated.

Our study was an optimized combination therapeutic strategy in which we strictly chose CHB patients who achieved lower baseline HBsAg levels (≤ 1500 IU/mL) after long-term NA treatment. Our data showed that the HBsAg clearance and seroconversion rates in the peg-IFN α-2a add-on group were 26.4% and 18.7% at week 48, and these rates increased to 37.4% and 29.7% at week 72, significantly higher than those patients receiving NA alone. Our results demonstrated significantly higher rates of HBsAg clearance and seroconversion than three previous studies that utilized peg-IFN α-2a instead of NA[11,16,17]. The major discrepancy between our study and those three studies is that the patients were not selected by baseline HBsAg levels and HBV DNA levels at enrollment in those three studies. In addition, sequential combination therapy with peg-IFN α-2a and NA, simultaneously exerting direct antiviral effect and immune regulation of the drugs, is another important reason for significantly higher rates of HBsAg clearance and seroconversion in our study.

However, a randomized controlled trial reported that the addition of 48 wk of peg-IFN α-2a to NA therapy resulted in a small proportion of HBsAg clearance and HBs seroconversion[18]. Several reasons could explain the discrepancy between our results and results in that randomized controlled trial. Firstly, 93.4% (85/91) of patients in our study finished the scheduled peg-IFN α-2a treatment and follow-up, while only 76% (65/85) of patients received the full dose and duration of peg-IFN α-2a treatment in that randomized controlled trial. Good compliance and tolerance to full dose and duration of peg-IFN α-2a treatment may be the main reason for significantly higher rates of HBsAg clearance and seroconversion in our study. Secondly, lower baseline HBsAg titer of patients in our study may be another important reason[19]. Furthermore, all patients in our study were CHB patients and the FibroScan value < 7.1 kPa, while about 35.0% (31/90) of patients had liver fibrosis and even cirrhosis in the randomized controlled trial. Lower baseline degree of liver fibrosis of patients in our study could well explain the discrepancy between these two studies[20].

Although 62.6% (57/91) patients in the add-on group did not achieve the primary end point, peg-IFN α-2a add-on therapy caused a greater decline in HBsAg levels and led to a higher proportion of patients achieving an HBsAg level < 3 log10 IU/mL and even < 2 log10 IU/mL than NA monotherapy, which are levels associated with long-term disease remission[21]. It suggests that we need to explore an individual treatment strategy for the peg-IFN α-2a regimen based on the kinetics of HBsAg rather than a 48-wk fixed-course treatment strategy.

From a practical point of view, early identification of patients with the highest chance of HBsAg clearance and particularly those with the lowest chance of HBsAg clearance after 48 wk of peg-IFN α therapy has the greatest clinical relevance. HBsAg at baseline and early decline during treatment have been shown to be useful for predicting eventual HBsAg elimination and in individualized on-treatment decision-making in a small cohort of patients[22]. Indeed, our study provides evidence to support this concept. In our study, we found that the levels of HBsAg at baseline, week 12 and week 24 and the decline of HBsAg during early therapy (at weeks 12 and 24) from baseline were all statistically associated with HBsAg clearance. Therefore, HBsAg at baseline, weeks 12 and 24 and decrease of HBsAg at weeks 12 and 24 were potential markers for the early prediction of HBsAg clearance in clinical practice.

ALT elevation induced by peg-IFN α-2a treatment reflects immune clearance of HBV. In our study, ALT elevations were observed in some patients with sustained HBV DNA suppression right after adding peg-IFN α-2a. Our analysis revealed that a significantly higher chance of HBsAg clearance in patients with ALT ≥ 2 × ULN during the first 12 wk of therapy than those patients with ALT < 2 × ULN. Therefore, ALT ≥ 2 × ULN during the first 12 wk of therapy is likely a promising marker for early prediction of HBsAg clearance in clinical practice. However, because of a small sample size of patients receiving peg-IFN α-2a add-on therapy (n = 91) in this study, further efforts with more patients enrolled and preferably in multiple centers is our next step to reach a validating conclusion.

Our results also showed that age was significantly associated with HBsAg clearance at week 72, which is consistent with previous studies[9]. Further analysis found that age ≤ 33 years was an important marker for early HBsAg clearance, suggesting that young patients have a better response to peg-IFN α-2a.

All the above variables and their “cut-off points” on ROC curves are meaningful for predicting HBsAg clearance. However, this study had a relatively small number of patients receiving peg-IFN α-2a add-on therapy (n = 91). Exploratory analyses into baseline and on-treatment predictors of HBsAg clearance should be interpreted with caution. As future research, more patients in multiple centers will be enrolled and these meaningful characteristics will be combined into a mathematically modelled and weighted scoring system that can be retrospectively and prospectively validated.

Considering safety, peg-IFN α-2a add-on was generally well tolerated without observing unexpected AEs. Indeed, AEs were increased when compared to NA monotherapy, which should be taken into account when considering peg-IFN α-2a add-on therapy. AEs should also be closely monitored and managed promptly during administration of peg-IFN α-2a. All AEs were reversed after drug withdrawal. Therefore, it is essential to communicate with patients adequately and encourage patients to comply with continuous peg-IFN α-2a therapy.

This study has several limitations. First, the patients in the treatment groups were not randomized. This may lead to confounder bias induced by unknown confounding factors and potentially impact the follow-up results, although demographic and baseline characteristics between treatment groups were not statistically different. Second, it is uncertain whether different HBV genotypes play a role in the response to the same therapeutic strategy due to unknown HBV genotypes in patients with long-term HBV suppression at entry to the study. Third, HBsAg decline during the treatment period does not certainly point to a long-term trend, and HBsAg levels may revert to the previous state after discontinuing peg-IFN α-2a. The long-term effectiveness data including HBsAg and HBV DNA dynamics, sustained HBsAg clearance, incidence of liver cirrhosis and HCC are being collected, and we will report in the future.

HBsAg elevations were observed at 4 wk after adding on peg-IFN α-2a in 57.1% (52/91) patients in the peg-IFN α-2a add-on group and had no influence on treatment outcome. It is an interesting phenomenon. The reason of HBsAg elevations after adding on peg-IFN α-2a therapy needs to be further explored.

In conclusion, this study shows that the peg-IFN α-2a add-on strategy in HBeAg-negative CHB patients with HBsAg ≤ 1500 IU/mL receiving long-term NA leads to higher HBsAg clearance than NA monotherapy. Young patients, lower levels of HBsAg at baseline, at weeks 12 and 24 and rapid HBsAg decline in early treatment (at weeks 12 and 24) are the independent predictors of HBsAg clearance in peg-IFN α-2a add on treatment. The add-on therapy is relatively safe, and the patients experience expected AEs.

Nucleos(t)ide analog (NA) has shown limited effectiveness against hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) clearance in chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients.

Despite promising results with the combination therapy of peginterferon (peg-IFN) and NA, the best combination therapeutic strategy of peg-IFN and NA for the treatment of CHB is still debated. The interim analysis of the NEW SWITCH study showed that patients with baseline HBsAg levels < 1500 IU/mL achieved a higher HBsAg clearance rate than patients with HBsAg > 1500 IU/mL when they switched from NA to 48 wk of peg-IFN α-2α therapy. However, it is not clear what the effects of add-on peginterferon α-2a to an ongoing NA regimen in CHB patients with HBsAg ≤ 1500 IU/mL after over 1 year of NA therapy. Considering the large number of patients who have achieved HBsAg ≤ 1500 IU/mL after long-term NA treatment in our clinic, it is very necessary and significant to explore the efficacy of peg-IFN α add-on treatment in these patients.

This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of add-on peg-IFN α-2a to an ongoing NA regimen in CHB patients with HBsAg ≤ 1500 IU/mL, hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)-negative and hepatitis B virus-deoxyribonucleic acid (HBV DNA) < 1.0 × 102 IU/mL after over 1 year of NA therapy and to analyze independent prediction factors of HBsAg clearance in this population.

In this observational study, 195 CHB patients with HBsAg ≤ 1500 IU/mL, HBeAg-negative (including HBeAg-negative patients or HBeAg-positive patients achieved HBeAg-negative after antiviral treatment with NA) and HBV DNA < 1.0 × 102 IU/mL after over 1 year of NA therapy were enrolled between November 2015 and December 2018 at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University, China. Patients were given the choice between receiving either peg-IFN α-2a add-on therapy to an ongoing NA regimen (add-on group, n = 91) or continuous NA monotherapy (monotherapy group, n = 104) after being informed of the benefits and risks of the peg-IFN α-2a therapy. Total therapy duration of peg-IFN α-2a was 48 wk. All patients were followed-up to week 72 (24 wk after discontinuation of peg-IFN α-2a). The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients with HBsAg clearance at week 72.

Demographic and baseline characteristics were comparable between the two groups. Intention-to-treatment analysis showed that the HBsAg clearance rate in the add-on group and monotherapy group was 37.4% (34/91) and 1.9% (2/104) at week 72, respectively. The HBsAg seroconversion rate in the add-on group was 29.7% (27/91) at week 72, and no patients in the monotherapy group achieved HBsAg seroconversion at week 72. The HBsAg clearance and seroconversion rates in the add-on group were significantly higher than in the monotherapy group at week 72 (P < 0.001). Younger patients, lower baseline HBsAg concentration, lower HBsAg concentrations at weeks 12 and 24, greater HBsAg decline from baseline to weeks 12 and 24 and the alanine aminotransferase ≥ 2 × upper limit of normal during the first 12 wk of therapy were strong predictors of HBsAg clearance in patients with peg-IFN α-2a add-on treatment. Regarding the safety of the treatment, 4.4% (4/91) of the patients in the add-on group discontinued peg-IFN α-2a due to adverse events. No severe adverse events were noted in the monotherapy group.

Peg-IFN α as an add-on therapy augments HBsAg clearance in HBeAg-negative CHB patients with HBsAg ≤ 1500 IU/mL after over 1 year of NA therapy.

Add-on Peg-IFN α to ongoing NA regime in CHB patients with low HBsAg levels and sustained HBV DNA suppression after long-term NA treatment can significantly improve the rates of HBsAg clearance and seroconversion. Some indicators, such as younger patients, lower HBsAg concentrations at baseline, weeks 12 and 24, greater HBsAg decline from baseline to weeks 12 and 24 and the alanine aminotransferase ≥ 2 × upper limit of normal during the first 12 wk of therapy can serve as predictors of HBsAg clearance in patients with peg-IFN α-2a add-on treatment. peg-IFN α add-on treatment is relatively safe. However,, the long-term efficacy of peg-IFN α add-on treatment needs to be studied.

The authors would like to thank Lei-Lei Pei from Institute of Public Health Xi’an Jiaotong University for reviewing the statistical methods of this study. The authors also would like to thank the patients and their families for their contribution to this study.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Fallatah H, Tanwar S, Yeoh SW S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address: easloffice@easloffice.eu.; European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL 2017 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2017;67:370-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3745] [Cited by in RCA: 3736] [Article Influence: 467.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Chang TT, Lai CL, Kew Yoon S, Lee SS, Coelho HS, Carrilho FJ, Poordad F, Halota W, Horsmans Y, Tsai N, Zhang H, Tenney DJ, Tamez R, Iloeje U. Entecavir treatment for up to 5 years in patients with hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2010;51:422-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 447] [Cited by in RCA: 463] [Article Influence: 30.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lau GK, Piratvisuth T, Luo KX, Marcellin P, Thongsawat S, Cooksley G, Gane E, Fried MW, Chow WC, Paik SW, Chang WY, Berg T, Flisiak R, McCloud P, Pluck N; Peginterferon Alfa-2a HBeAg-Positive Chronic Hepatitis B Study Group. Peginterferon Alfa-2a, lamivudine, and the combination for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2682-2695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1188] [Cited by in RCA: 1169] [Article Influence: 58.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Janssen HL, van Zonneveld M, Senturk H, Zeuzem S, Akarca US, Cakaloglu Y, Simon C, So TM, Gerken G, de Man RA, Niesters HG, Zondervan P, Hansen B, Schalm SW; HBV 99-01 Study Group; Rotterdam Foundation for Liver Research. Pegylated interferon alfa-2b alone or in combination with lamivudine for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;365:123-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 918] [Cited by in RCA: 903] [Article Influence: 45.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | You CR, Lee SW, Jang JW, Yoon SK. Update on hepatitis B virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:13293-13305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 6. | European Association For The Study Of The Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: Management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2012;57:167-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2323] [Cited by in RCA: 2398] [Article Influence: 184.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lampertico P, Liaw YF. New perspectives in the therapy of chronic hepatitis B. Gut. 2012;61 Suppl 1:i18-i24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Scaglione SJ, Lok AS. Effectiveness of hepatitis B treatment in clinical practice. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1360-1368.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hou J, Wang G, Wang F, Cheng J, Ren H, Zhuang H, Sun J, Li L, Li J, Meng Q, Zhao J, Duan Z, Jia J, Tang H, Sheng J, Peng J, Lu F, Xie Q, Wei L; Chinese Society of Hepatology, Chinese Medical Association; Chinese Society of Infectious Diseases, Chinese Medical Association. Guideline of Prevention and Treatment for Chronic Hepatitis B (2015 Update). J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2017;5:297-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sarin SK, Kumar M, Lau GK, Abbas Z, Chan HL, Chen CJ, Chen DS, Chen HL, Chen PJ, Chien RN, Dokmeci AK, Gane E, Hou JL, Jafri W, Jia J, Kim JH, Lai CL, Lee HC, Lim SG, Liu CJ, Locarnini S, Al Mahtab M, Mohamed R, Omata M, Park J, Piratvisuth T, Sharma BC, Sollano J, Wang FS, Wei L, Yuen MF, Zheng SS, Kao JH. Asian-Pacific clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatitis B: a 2015 update. Hepatol Int. 2016;10:1-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1985] [Cited by in RCA: 1928] [Article Influence: 214.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ning Q, Han M, Sun Y, Jiang J, Tan D, Hou J, Tang H, Sheng J, Zhao M. Switching from entecavir to PegIFN alfa-2a in patients with HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B: a randomised open-label trial (OSST trial). J Hepatol. 2014;61:777-784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Boglione L, Cariti G, Di Perri G, D'Avolio A. Sequential therapy with entecavir and pegylated interferon in a cohort of young patients affected by chronic hepatitis B. J Med Virol. 2016;88:1953-1959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wursthorn K, Lutgehetmann M, Dandri M, Volz T, Buggisch P, Zollner B, Longerich T, Schirmacher P, Metzler F, Zankel M, Fischer C, Currie G, Brosgart C, Petersen J. Peginterferon alpha-2b plus adefovir induce strong cccDNA decline and HBsAg reduction in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2006;44:675-684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 342] [Cited by in RCA: 349] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ouzan D, Pénaranda G, Joly H, Khiri H, Pironti A, Halfon P. Add-on peg-interferon leads to loss of HBsAg in patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis and HBV DNA fully suppressed by long-term nucleotide analogs. J Clin Virol. 2013;58:713-717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chen GY, Zhu MF, Zheng DL, Bao YT, Wang J, Zhou X, Lou GQ. Baseline HBsAg predicts response to pegylated interferon-α2b in HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:8195-8200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hu P, Shang J, Zhang W, Gong G, Li Y, Chen X, Jiang J, Xie Q, Dou X, Sun Y, Li Y, Liu Y, Liu G, Mao D, Chi X, Tang H, Li X, Xie Y, Chen X, Jiang J, Zhao P, Hou J, Gao Z, Fan H, Ding J, Zhang D, Ren H. HBsAg Loss with Peg-interferon Alfa-2a in Hepatitis B Patients with Partial Response to Nucleos(t)ide Analog: New Switch Study. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2018;6:25-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | He LT, Ye XG, Zhou XY. Effect of switching from treatment with nucleos(t)ide analogs to pegylated interferon α-2a on virological and serological responses in chronic hepatitis B patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:10210-10218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bourlière M, Rabiega P, Ganne-Carrie N, Serfaty L, Marcellin P, Barthe Y, Thabut D, Guyader D, Hezode C, Picon M, Causse X, Leroy V, Bronowicki JP, Carrieri P, Riachi G, Rosa I, Attali P, Molina JM, Bacq Y, Tran A, Grangé JD, Zoulim F, Fontaine H, Alric L, Bertucci I, Bouvier-Alias M, Carrat F; ANRS HB06 PEGAN Study Group. Effect on HBs antigen clearance of addition of pegylated interferon alfa-2a to nucleos(t)ide analogue therapy versus nucleos(t)ide analogue therapy alone in patients with HBe antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B and sustained undetectable plasma hepatitis B virus DNA: a randomised, controlled, open-label trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:177-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Liem KS, van Campenhout MJH, Xie Q, Brouwer WP, Chi H, Qi X, Chen L, Tabak F, Hansen BE, Janssen HLA. Low hepatitis B surface antigen and HBV DNA levels predict response to the addition of pegylated interferon to entecavir in hepatitis B e antigen positive chronic hepatitis B. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49:448-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Patel K, Wilder J. Fibroscan. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2014;4:97-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sonneveld MJ, Rijckborst V, Cakaloglu Y, Simon K, Heathcote EJ, Tabak F, Mach T, Boucher CA, Hansen BE, Zeuzem S, Janssen HL. Durable hepatitis B surface antigen decline in hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B patients treated with pegylated interferon-α2b: relation to response and HBV genotype. Antivir Ther. 2012;17:9-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kittner JM, Sprinzl MF, Grambihler A, Weinmann A, Schattenberg JM, Galle PR, Schuchmann M. Adding pegylated interferon to a current nucleos(t)ide therapy leads to HBsAg seroconversion in a subgroup of patients with chronic hepatitis B. J Clin Virol. 2012;54:93-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |