Published online Jan 7, 2020. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i1.35

Peer-review started: September 26, 2019

First decision: November 4, 2019

Revised: December 6, 2019

Accepted: December 13, 2019

Article in press: December 13, 2019

Published online: January 7, 2020

Processing time: 103 Days and 4.5 Hours

Abdominal paracentesis drainage (APD) is a safe and effective strategy for severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) patients. However, the effects of APD treatment on SAP-associated cardiac injury remain unknown.

To investigate the protective effects of APD on SAP-associated cardiac injury and the underlying mechanisms.

SAP was induced by 5% sodium taurocholate retrograde injection in Sprague-Dawley rats. APD was performed by inserting a drainage tube with a vacuum ball into the lower right abdomen of the rats immediately after SAP induction. Morphological staining, serum amylase and inflammatory mediators, serum and ascites high mobility group box (HMGB) 1, cardiac-related enzymes indexes and cardiac function, oxidative stress markers and apoptosis and associated proteins were assessed in the myocardium in SAP rats. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase activity and mRNA and protein expression were also examined.

APD treatment improved cardiac morphological changes, inhibited cardiac dysfunction, decreased cardiac enzymes and reduced cardiomyocyte apoptosis, proapoptotic Bax and cleaved caspase-3 protein levels. APD significantly decreased serum levels of HMGB1, inhibited nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase expression and ultimately alleviated cardiac oxidative injury. Furthermore, the activation of cardiac nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase by pancreatitis-associated ascitic fluid intraperitoneal injection was effectively inhibited by adding anti-HMGB1 neutralizing antibody in rats with mild acute pancreatitis.

APD treatment could exert cardioprotective effects on SAP-associated cardiac injury through suppressing HMGB1-mediated oxidative stress, which may be a novel mechanism behind the effectiveness of APD on SAP.

Core tip: In the present study, we provided the first evidence that abdominal paracentesis drainage (APD) treatment exerts beneficial effects on severe acute pancreatitis-associated cardiac injury. Our key findings are that (1) APD treatment decreases the serum levels of cardiac enzymes and improves cardiac function; (2) APD treatment alleviates cardiac oxidative stress and accompanied cardiomyocyte apoptosis; and (3) The beneficial effects of APD treatment in ameliorating severe acute pancreatitis-associated cardiac injury are due to the inhibition of oxidative damage via downregulating high mobility group box 1-mediated nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase expression. Our data manifest that APD is a promising treatment in severe acute pancreatitis-associated cardiac injury.

- Citation: Wen Y, Sun HY, Tan Z, Liu RH, Huang SQ, Chen GY, Qi H, Tang LJ. Abdominal paracentesis drainage ameliorates myocardial injury in severe experimental pancreatitis rats through suppressing oxidative stress. World J Gastroenterol 2020; 26(1): 35-54

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v26/i1/35.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v26.i1.35

Severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) is a fatal abdominal disease and usually complicated with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome[1]. SAP-associated cardiac injury (SACI) occurs in some patients, and cardiac decompensation even causes death[2-4]. SACI frequently exhibits cardiomyocyte hypoxia, apoptosis and hypertrophy and can even lead to death[4,5]. Recent studies have shown that the elevated levels of myocardial enzymes are associated with the severity and outcome of SAP[6]. Despite constant understanding of the pathogenesis of SAP and significant improvement in clinical management, the mortality rate remains high, and the incidence rate of related complications is still unacceptable. Therefore, it is necessary to develop novel treatment strategies for improving cardiac injury and outcomes in SAP patients.

In our previous clinical study, early abdominal paracentesis drainage (APD) effectively relieved or controlled the severity of SAP, and this treatment strategy was an important development and supplement for the minimally invasive step-up approach[7]. Through removal of pancreatitis-associated ascitic fluid (PAAF), APD exerts beneficial effects supported by a delay or avoidance of multiple organ failure, decreased mortality rate and no increase in infection in patients with SAP[8,9]. Experimental evidence also indicates the effectiveness of APD treatment on SAP-associated lung and intestinal mucosa injury in rats[10,11]. However, the effect of APD treatment on SACI and the potential underlying mechanisms are yet to be elucidated.

Recently, high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), a DNA-binding intranuclear protein, has attracted increasing attention because of its vital role as a late mediator in lethal systemic inflammation[12,13]. HMGB1 is derived from active secretion by activated macrophages and passive secretion by necrotic and apoptotic cells. Extracellular HMGB1 can trigger a lethal inflammatory process and participate in the development of multiple organ injury in SAP[14,15]. It has been reported that serum HMGB1 level is significantly elevated in patients with SAP on admission and is positively related to severity of SAP as well as organ dysfunction and infection during the clinical course[16]. In particular, the level of HMGB1 in PAAF is higher compared with that in serum in experimental SAP, indicating that HMGB1 is first produced and released by the pancreas and peritoneal macrophages/monocytes during SAP[17]. In addition, HMGB1 plays an important role in the pathogenesis of cardiac dysfunction in many diseases. Active neutralization with anti-HMGB1 antibodies or HMGB1-specific blockage via box A could prevent cardiac dysfunction in mice with ischemia-reperfusion injury[18], sepsis[19] and diabetic cardiomyopathy[20]. Therefore, we propose that APD treatment by draining PAAF may decrease the level of HMGB1 in serum, thereby exerting a protective role in SACI.

The role of oxidative injury in the development of SACI has been demonstrated[4,21]. It is suggested that HMGB1 causes increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) through activation of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase oxidases (NOXs)[22]. NOX acts as a major source of ROS in the heart in pathological conditions[23]. Our recent study has confirmed that NOX hyperactivity contributes to cardiac dysfunction and apoptosis in rats with SAP[24]. Despite these advances, whether APD influences oxidative stress via HMGB1-mediated cardiac NOX is not known.

Based on these findings, we hypothesized that APD treatment could protect rats from cardiac injury induced by SAP via antioxidative stress, through inhibiting HMGB1/NOX signaling. To test this hypothesis, we systematically investigated the role of APD treatment in SACI and determined whether HMGB1 plays a pivotal role during this treatment process.

The sodium taurocholate was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). The dihydroethidium (DHE) was purchased from Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology (Haimen, China). The antibody for HMGB1 (BM3965) was purchased from Boster Biological Technology, Inc. (Wuhan, China). The antibody specific for apoptosis regulator Bax (cat. No. ab32503), NOX2/gp91phox (cat. No. ab31092) and NOX4 (cat. No. ab133303) were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, United Kingdom). The antibody for caspase-3 (cat. No. 9662S) was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, United States). The antibody for apoptosis regulator protein Bcl-2 (cat. No. GTX100064) was purchased from GeneTex Inc. (Irvine, CA, United States). All other chemicals used in this study were of analytical grade and were commercially available.

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (weight, 200-220 g) were used in this study. The animals were purchased from Chengdu Dossy Animal Science and Technology Co. Ltd. (Chengdu, China). They were kept separately in an individually ventilated cage system maintained at 23 °C with a 12-h light/dark cycle and fed with standard laboratory food and water ad libitum for 3 d prior to the experiments. The animals were fasted overnight prior to the experiment but had free access to water. The experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Chengdu Military General Hospital and were conducted in accordance with the established International Guiding Principles for Animal Research.

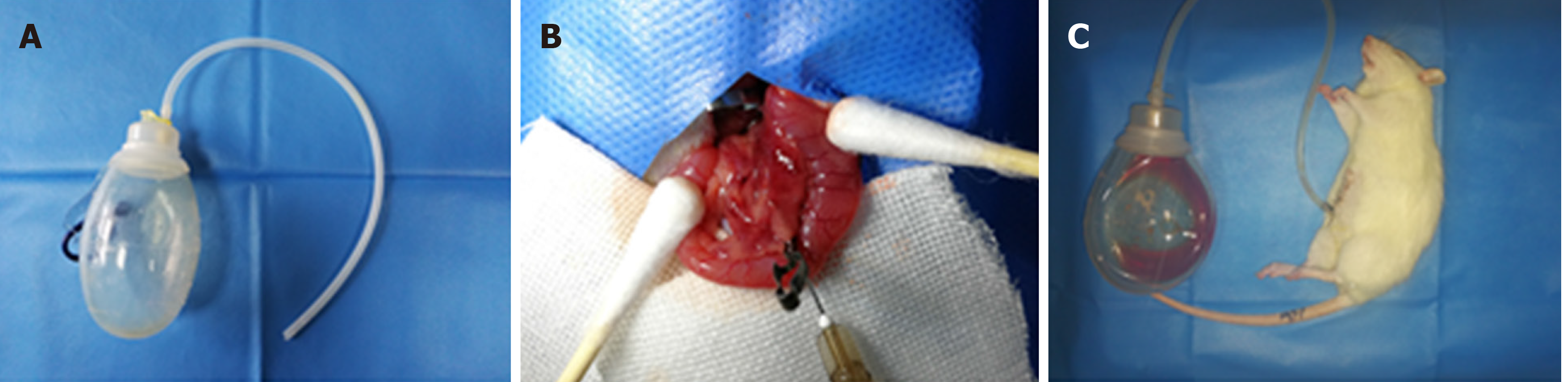

In the first series of experiments, 45 rats were randomly divided into three groups of 15: sham operation, SAP and SAP + APD. The rats were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane (via an induction box) prior to surgery. The SAP model was induced by a standardized pressure-controlled retrograde infusion of 5% sodium taurocholate into the biliopancreatic duct at a rate of 12 mL/h using a micro-infusion pump (0.13 mL/100 g body weight); the microvascular clamp and puncture needle were removed after 5 min. The abdomen was closed according to the classical method of Chen et al[25] with modifications. In the SAP + APD group, a drainage tube connected to a negative-pressure ball device was inserted into the lower right abdomen immediately following SAP induction (Figure 1). Following the operation, all rats received 10 mL/200 g body weight of sterile saline by subcutaneous injection in the back to compensate for anticipated fluid loss. For the sham operation group, an incision was made in the abdomen and was subsequently closed. The animals were denied access to food or water for 24 h after the procedure.

The second experiment was designed to determine whether cardiac NOX activated by HMGB1 was involved in the beneficial effects of APD treatment. Another 36 rats with mild acute pancreatitis (MAP) were used. MAP was induced by six consecutive intraperitoneal injections of cerulein (20 μg/kg at 1-h intervals) as previously described[21]. Fresh PAAF was aseptically obtained from the abdominal cavity of rats with SAP in the first experiment, and the sterile supernatant was collected after centrifuged at 4000 x g for 15 min at 4 °C. The rats with MAP were randomly divided into the following six groups of six: (1) Controls: rats were intraperitoneally injected with 8 mL saline solution; (2) PAAF injection (PI): rats were intraperitoneally injected with 8 ml of PAAF; (3) PAAF + anti-HMGB1 neutralizing antibody 50 μg (PIH 50): rats were intraperitoneally injected with 8 mL PAAF and 50 μg anti-HMGB1 neutralizing antibody; (4) PAAF + anti-HMGB1 neutralizing antibody 100 μg (PIH 100): rats were intraperitoneally injected with 8 mL PAAF and 100 μg anti-HMGB1 neutralizing antibody; (5) PAAF + anti-HMGB1 neutralizing antibody 200 μg (PIH 200): rats were intraperitoneally injected with 8 mL PAAF and 200 μg anti-HMGB1 neutralizing antibody; and (6) PAAF + control IgY 200 μg: rats were intraperitoneally injected with 8 mL PAAF and 200 μg control IgY. Nonimmune chicken IgY (Boster Biological Technology, Wuhan, China) acted as a control antibody for HMGB1 neutralization. Anti-HMGB1 neutralizing antibody (rabbit anti-HMGB1 monoclonal antibody) recognized rat HMGB1. The specificity and neutralizing activity of this antibody was confirmed by western blotting. PAAF and anti-HMGB1 neutralizing antibody were previously incubated at 36 °C for 30 min. Eight hours after the injections, rats were anesthetized, and blood and heart tissues were collected, immediately frozen and stored at -80 °C until use.

At 24 h after induction of SAP, all rats were anesthetized by 5% isoflurane, and echocardiography was performed using LOGIQ E9 ultrasound apparatus (GE, Boston, MA, United States) equipped with a 12-MHz transducer. Heart rate, left ventricular end-diastolic dimension and left ventricular end-systolic dimension were measured, and left ventricular ejection fraction and fractional shortening were calculated from M-mode recordings. Measurements were analyzed by a blinded observer, and all the results were averaged from five consecutive cardiac cycles measuring from the M-mode images. Following the measurements, blood pressure was assessed using the AD Instruments PowerLab system (Bella Vista, NSW, Australia). In the process of this measurement, a microtip catheter transducer (22G IV cannula; ShiFeng, Inc., Chengdu, China) was gradually inserted 2 cm into the right carotid artery. The signals were continuously recorded, and systolic and diastolic pressure were processed using LabChart 7 (version 7.3.7) analytical software. After completion of all the measurements, under strict aseptic conditions, PAAF was obtained from the abdominal cavity of rats with SAP, blood samples were collected from the ventral aorta, serum was obtained by centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C and an appropriate number of aliquots were separated and stored at -80 °C until use. The pancreas and heart were quickly removed, and part of the pancreas and left ventricle were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde or flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen until use.

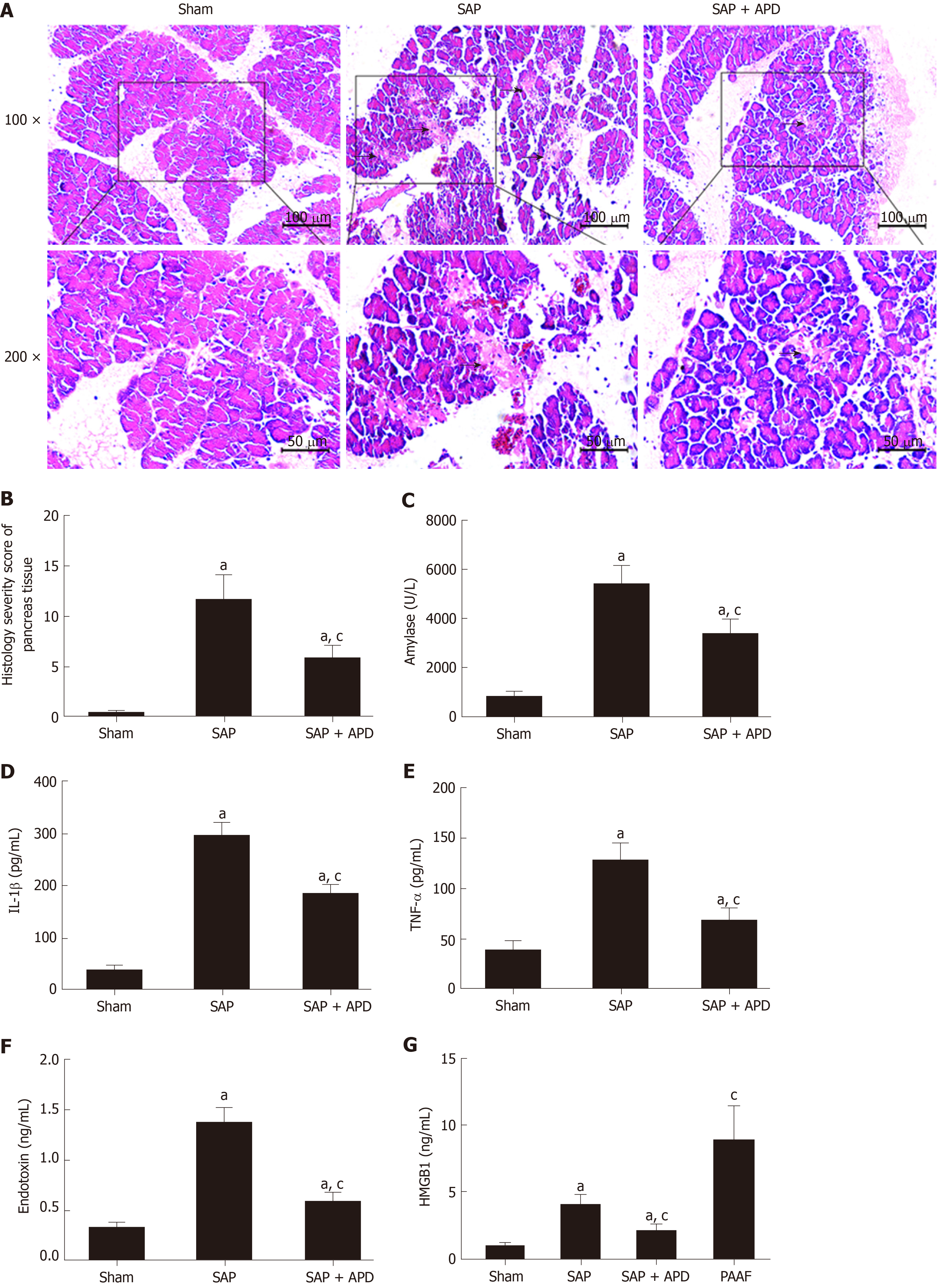

Twenty-four hours after SAP induction, the terminal pancreas and heart tissue samples were paraformaldehyde-fixed, paraffin-embedded and sectioned at 4 μm. The sections were then stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The slides were read by a consultant histopathologist blinded to the groups under Leica DM 3000 light microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany) with a digital photography system (Leica application suite, version 4.4.0). For the heart, we assessed interstitial edema, hemorrhage, neutrophil infiltration and contraction band necrosis[26]. For the pancreas, the severity of pancreatic injury was evaluated based on a 0-4 scoring method, the scores of several parameters including edema, fat necrosis, hemorrhage, inflammatory cell infiltrate and acinar necrosis[27].

The heart was placed in a preweighed plastic bag, weighed again (wet), then samples were oven-dried at 57 °C for 48 h and reweighed (dry). The edema index was calculated as: Edema Index = Weight (wet)/Weight (dry).

Serum HMGB1, TNF-α, endotoxin, IL-1β, creatine kinase-MB, cardiac troponin-I and HMGB1 in PAAF were detected using an enzyme linked immunosorbent assay kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The serum levels of amylase and lactate dehydrogenase were measured according to the manufacturer's instructions using an automatic biochemistry analyzer (TC6010L; Tecom Science Corporation, Jiangxi, China).

To determine the degree of oxidative stress in the heart, lipid peroxidation (LPO), superoxide dismutase (SOD) and reduced glutathione (GSH) were measured in heart homogenates. Heart tissue (0.1 g) was collected and homogenized in ice-cold normal saline (weight:volume = 1:9). The homogenates used for the determination of SOD activities and LPO and GSH levels were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C, and the supernatants were collected. SOD activity and LPO and GSH levels were measured with test kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, China). To detect myocardial NOX activity, 0.5 g heart tissue was collected, washed with reagent buffer and then placed in cryogenic vials to stay overnight in liquid nitrogen. The next day, we ground the tissue into powder and added lysis buffer for 30 min under ice-cold conditions. After centrifugation at 10000 g for 10 min at 4 °C, the supernatants were collected. NOX activity in the samples was measured with test kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute). Protein quantification was performed using the Bradford method.

ROS can oxidate DHE, which forms ethidium bromide. This will intercalate DNA, which will emit red fluorescence. Frozen rat heart tissues were analyzed using DHE. Myocardium cross-sections (10 μm) were incubated with DHE (5 μmol/L) in PBS in a light-protected incubator at 37 °C for 30 min. The sections were washed three times with PBS to remove excess DHE. Red fluorescence was assessed by fluorescence microscope (IX81; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with green light. The ROS content increased in proportion to the intensity of red fluorescence. Quantitative analysis of fluorescent images was performed with Image J (NIH, United States) software and expressed as arbitrary units of fluorescence.

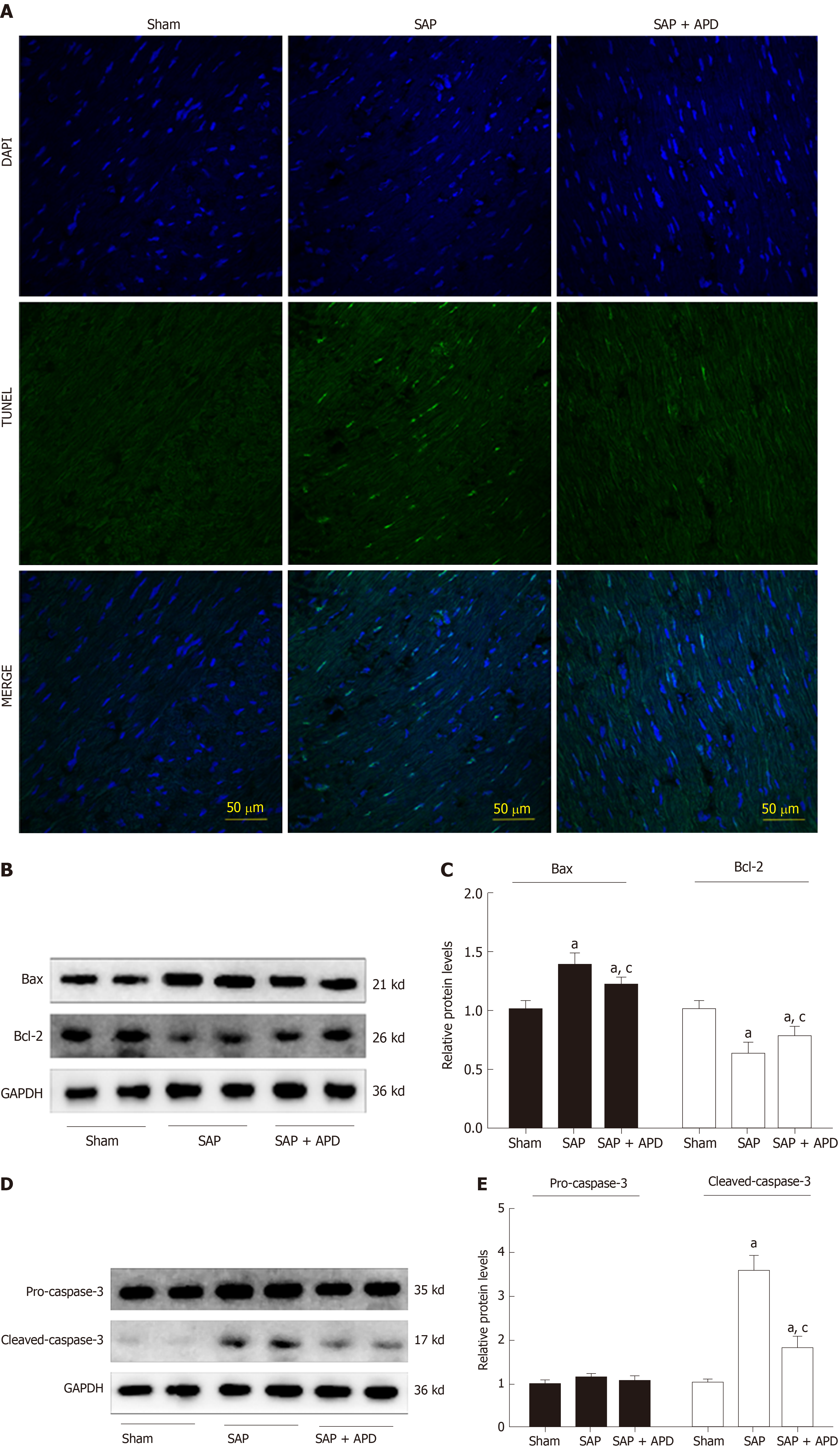

Myocardium frozen sections (10 μm) were used to detect the myocardial cells apoptosis with a terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling assay kit (Fluorescein in situ cell death detection kit; Boster biological Technology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China). According to the manufacturer's instructions, all of the cells showed blue nuclear DAPI staining, but the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling positive cells display green nuclear staining. The stained slices were analyzed by laser-scanning confocal microscopy (Eclipse ti2; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Total RNA was extracted from heart tissue using TRIzol reagent (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China), which is an RNA extraction kit. RNA purity and concentration were determined using the Thermo NanoDrop-2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, United States) at A260/A280 nm. The purity of RNA obtained was 1.8-2.0. The primers were synthesized by Sangon Biotech Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China) (Table 1). Reverse transcription of RNA and PCR amplification were performed with One Step SYBR PrimeScript TM RT-PCR Kit II (Takara Biotechnology, Dalian, China) by C1000 TM Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, United States). The cycling program was as follows: 5 min at 42 °C, 10 s at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 5 s at 95 °C and 30 s at 60 °C and then dissociation. The reactions were quantified according to the amplification cycles when the PCR products of interest were first detected (threshold cycle, Ct). Each reaction was performed in triplicate. The expression of the transcripts was normalized to the levels of β-actin in the samples. Data were analyzed using CFX Manager TM Software 1.6 (Bio-Rad).

| Gene | Primer sequences | |

| NOX2 | Forward | 5′-GACCATTGCAAGTGAACACCC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-AAATGAAGTGGACTCCACGCG-3′ | |

| NOX4 | Forward | 5′-TTCGCGGATCACAGAAGGTC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-AAGTTCAGGGCGTTCACCAA-3′ | |

| β-actin | Forward | 5′-ACGGTCAGGTCATCACTATCG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GGCATAGAGGTCTTTACGGATG-3′ |

The proteins from the rat left-ventricular tissue or cells were extracted using a protein extraction kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute). The protein concentrations were measured using an enhanced BCA Protein Assay kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute). Equal amounts of protein for each sample were separated by SDS-PAGE in a minigel apparatus (MiniPROTEAN II; Bio-Rad). Then they were transferred to a 0.22- or 0.40-μm polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline/Tween 20 and were incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-NOX2 (1:2000), anti-NOX4 (1: 5000), anti-Bax (1:2000), anti-Bcl-2 (1:1000), anti-caspase-3 (1:1000) and anti-GADPH (1:5000; loading control) antibodies. After incubation with horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody, Chemiluminescence Detection Reagent (Millipore, Billerica, MA, United States) was added drop-wise onto the membranes. Then the membranes were examined with the BioSpectrum4 apparatus (UVP, Upland, CA, United States).

All data are presented as mean ± SD and analyzed using SPSS version 18.0 (Chicago, IL, United States). Normally distributed data were compared using a one-way analysis of variance followed by the SNK test for multiple comparisons, and nonparametrically distributed variables were compared by the Mann-Whitney test with Bonferroni corrections. Values of P < 0.05 was recognized as statistically significant.

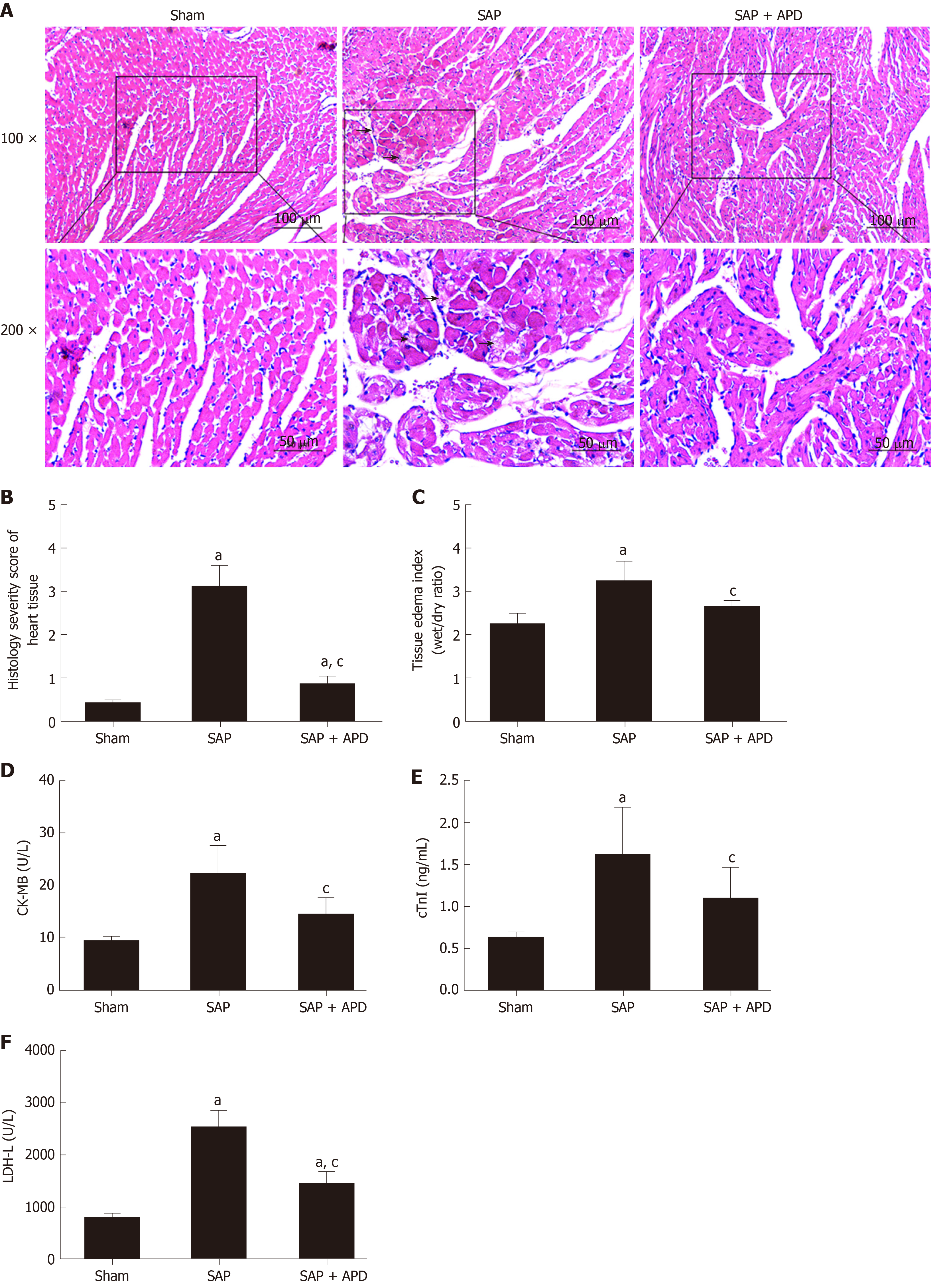

To study the effect of APD treatment on cardiac injury in a sodium-taurocholate-induced SAP rat model, we examined cardiac histopathology, tissue edema index and cardiac-related enzymes. The sham group showed normal myocardial architecture, whereas SAP rats exhibited obvious structural and cellular changes, including myocardial degeneration, cellular edema and mononuclear infiltration (Figure 2A). This result was consistent with early changes in myocarditis demonstrated by the histology severity score and tissue edema index (Figure 2B and 2C). Compared with the SAP group, the cardiac lesion in the SAP + APD group was mild with normal structure, and the score and tissue edema index were lower than those in the SAP group. The serum levels of cardiac-related enzymes were sensitive and specific indexes to reflect cardiac lesions. Compared with the sham group, the serum levels of cardiac enzymes in the SAP groups increased significantly (P < 0.01) (Figure 2D-2F). However, the levels of cardiac enzymes in the SAP + APD group were significantly lower compared with those in the SAP group (P < 0.01), especially creatine kinase-MB and cardiac troponin-I, which are specific indexes of cardiac injury. These results suggested that APD treatment preserved histopathology and decreased the levels of cardiac-related enzymes.

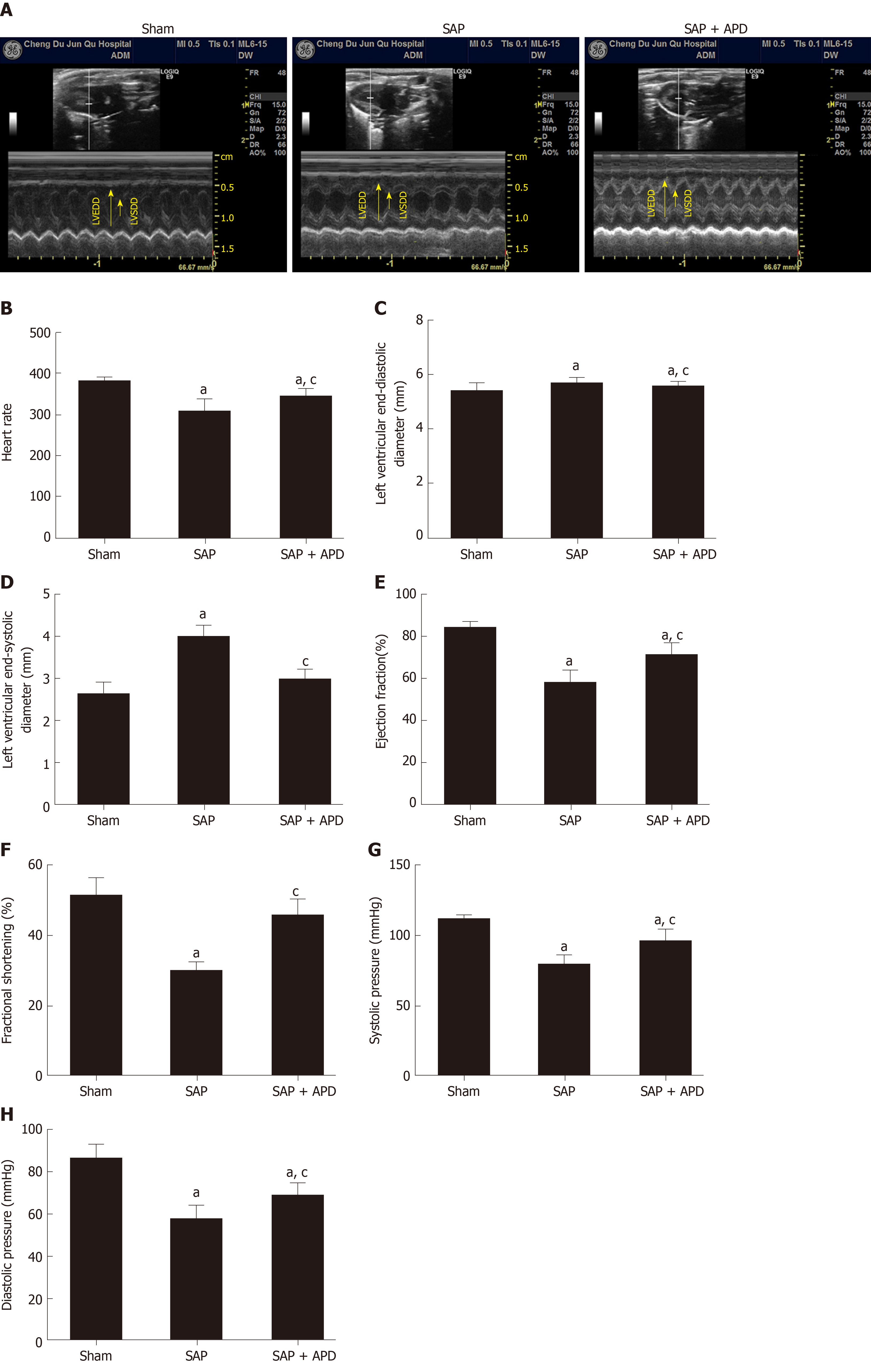

To evaluate the effect of APD treatment on cardiac functional abnormality caused by SAP, echocardiographic and hemodynamic changes were recorded 24 h after SAP challenge. Echocardiography was a sensitive indicator of cardiac function during SAP. Figure 3A-3F shows representative M-mode images and parameters from echocardiographic analysis. No significant differences were evidenced among the three groups in terms of left ventricular end-diastolic dimension. Compared with the sham group, increasing left ventricular end-systolic dimension was observed in SAP, but the increased level was attenuated by APD treatment. Heart rate, fractional shortening and ejection fraction decreased significantly after SAP challenge, but this was reversed with APD treatment. In the hemodynamic change evaluation, blood pressure was measured. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure were significantly reduced in the SAP group compared with the sham group (Figure 3G and 3H). APD treatment improved systolic and diastolic blood pressure at 24 h after SAP challenge. The results indicated that APD treatment attenuated cardiac function in SAP rats.

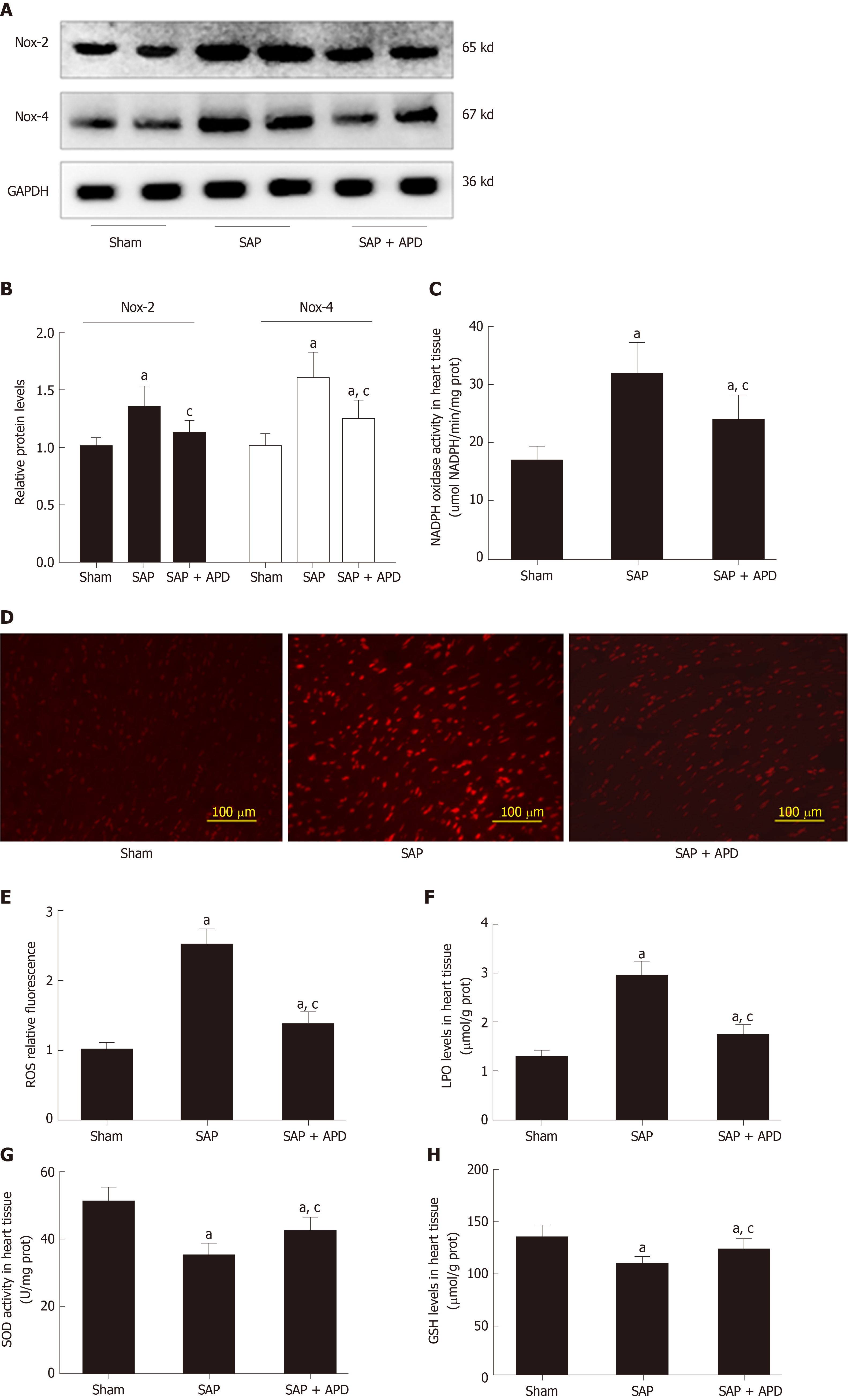

Given that NOX hyperactivity plays an important role in cardiac dysfunction in rats with SAP, we measured the effect of APD treatment on protein expression of NOX2 and NOX4 in myocardial tissue in SAP rats. Western blotting manifested that NOX2 and NOX4 in the myocardium were significantly increased in SAP compared with the sham group, in accordance with enhanced activity of NOX (Figure 4). APD treatment markedly decreased expression of NOX2 and NOX4. These results were further confirmed by assessing DHE oxidation in which a remarkable increase in ROS production was noted in myocardial tissue in SAP group compared with the sham group. APD treatment resulted in a decrease in ROS level in the sham group compared to the SAP group. Given that accumulated ROS can cause oxidative damage, we found an increase in LPO level and a decrease in SOD activity and GSH level in line with the observed changes in ROS content in the SAP group. After treatment with APD, the SOD activity and GSH level in the SAP + APD group were higher and the LPO level was lower than in the SAP group. These data suggest that APD treatment reduced ROS production and oxidative damage in the heart induced by SAP.

Given that the degree of myocardial apoptosis secondary to oxidative stress reflects the extent of myocardial injury, we used terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling to measure myocardial cell apoptosis. The apoptotic index was significantly increased in the SAP group (26.36 ± 4.54 vs 0.0 ± 0.0, P < 0.01) compared with the sham group (Figure 5A). APD treatment induced a significant decrease in apoptosis (6.35 ± 2.19 vs 26.36 ± 4.54, P < 0.01) in the sham group compared with the SAP group. Furthermore, apoptosis-associated protein expression was analyzed by western blotting. APD treatment downregulated the levels of proapoptotic Bax and cleaved caspase-3, and upregulated antiapoptotic Bcl-2 levels (Figure 5B-5E). These results confirmed that APD treatment relieved myocardial injury in SAP rats.

Considering that the key feature of acute pancreatitis is damage to the pancreas, we evaluated the effect of APD treatment on pancreatic injury and inflammatory indexes in SAP and measured changes in pancreatic histopathology, amylase activity and levels of proinflammatory cytokines. For pancreatic histopathology, hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections of rat pancreas tissue were analyzed. The sham group exhibited normal pancreatic structures while the SAP group displayed notable morphological changes with large areas of tissue necrosis and inflammatory infiltration, supported by the histological severity scores (Figure 6A and 6B). Compared with the features of the SAP group, the pancreatic damage in the SAP + APD group was significantly alleviated with a lower severity score. Furthermore, as shown in Figure 6C-6F, the serum amylase activity and levels of IL-1β, TNF-α and endotoxin in the SAP group were significantly increased compared with those in the sham group (P < 0.05). APD treatment after SAP induction resulted in a marked decrease in the levels of these indexes (P < 0.05).

Given that HMGB1 acts as a key inflammatory mediator and plays an important role in the course of lethal systemic inflammatory response and distant organ injury, we compared the levels of HMGB1 in PAAF and serum samples with or without APD treatment. Twenty-four hours after SAP induction, we found that serum HMGB1 level was significantly higher than that in sham rats. HMGB1 level in PAAF was higher than that in serum (Figure 6G). The results were consistent with previous studies, suggesting that HMGB1 is produced and released by the pancreas and peritoneal macrophages/monocytes in response to inflammatory mediators during SAP. Because APD treatment is a strategy for removing PAAF directly, we predicted that it would reduce the circulating concentration of HMGB1. As expected, serum HMGB1 level in SAP + APD rats was markedly reduced compared with that in the SAP group (Figure 6G). These data demonstrated that APD treatment, by removing PAAF, significantly decreased the serum level of HMGB1 in SAP rats, suggesting that HMGB1 signaling is responsible for the cardioprotective effects of APD.

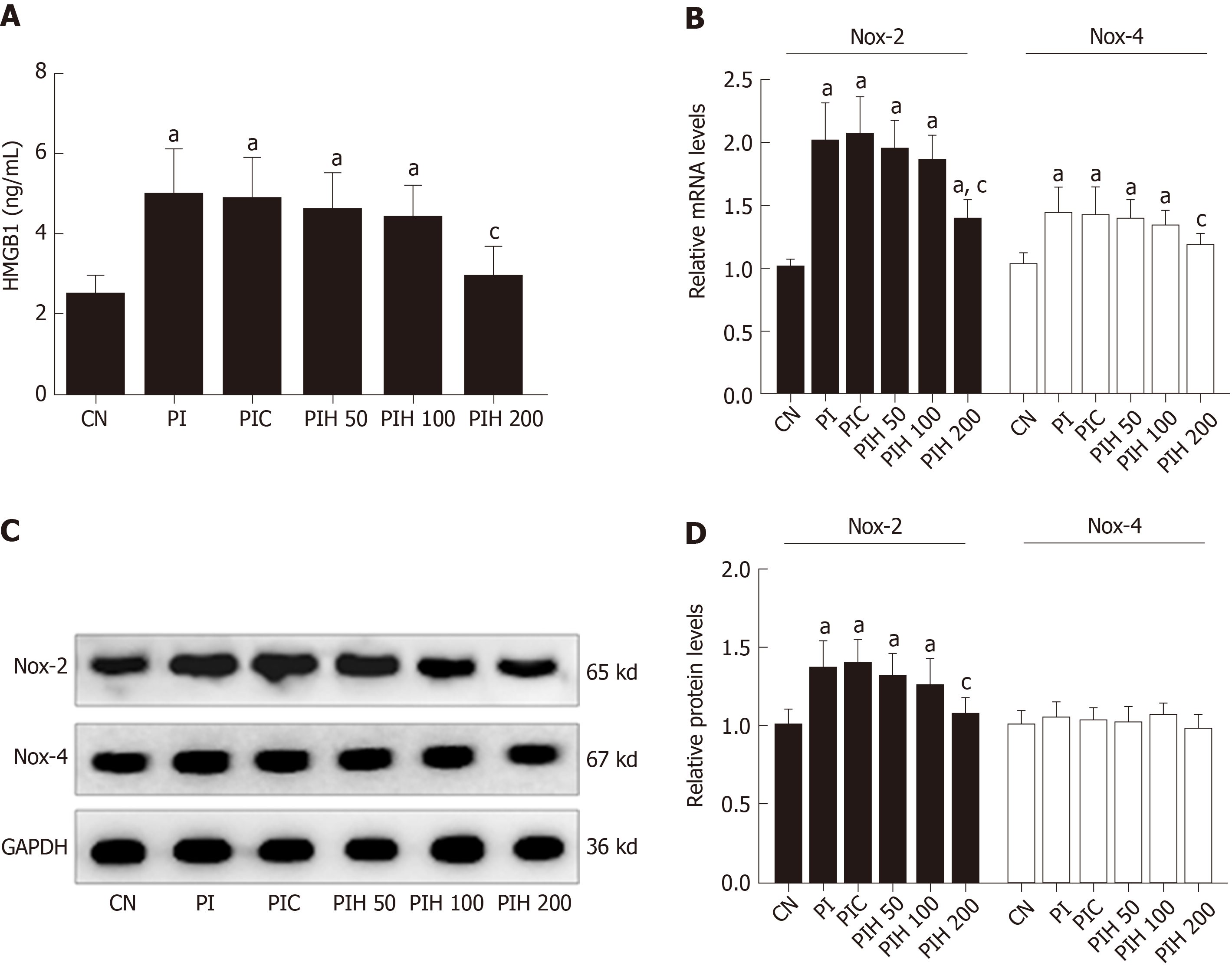

HMGB1 plays an important role in the pathogenesis of cardiac injury in many diseases; therefore, we determined whether HMGB1 in PAAF affected cardiac NOX expression. We intraperitoneally injected PAAF or PAAF + anti-HMGB1 neutralizing antibody (PI and PIH groups, respectively) and investigated the expression of NOX in heart samples from rats with MAP. We measured the serum level of HMGB1 after intraperitoneal injection of PAAF, with or without HMGB1 neutralizing antibody. The circulating level of HMGB1 in the PI group was significantly higher than that in the control group, suggesting that HMGB1 in PAAF could enter the bloodstream (Figure 7A). With the injection of HMGB1 neutralizing antibody into PAAF, we observed that when the dose was increased to 200 μg, the serum level of HMGB1 was significantly decreased compared with that in the PI group.

Next, we examined the influence of HMGB1 in PAAF on mRNA and protein expression of NOX2 and NOX4 from the heart (Figure 7B). Eight hours after injection, the mRNA and protein expression of NOX2 was significantly increased in the PI group compared with the control group, while only NOX4 mRNA expression was affected. The effects on expression in the PAAF + control IgY 200 μg group were similar to those in the PI group. In the 200 μg HMGB1 neutralizing antibody group, mRNA expression of NOX2 and NOX4 and protein expression of NOX2 was reduced compared with that in the PI group. These results demonstrated that high concentration of HMGB1 in PAAF could lead to NOX overexpression, and the decreased HMGB1 level caused by APD treatment results in reduced NOX expression.

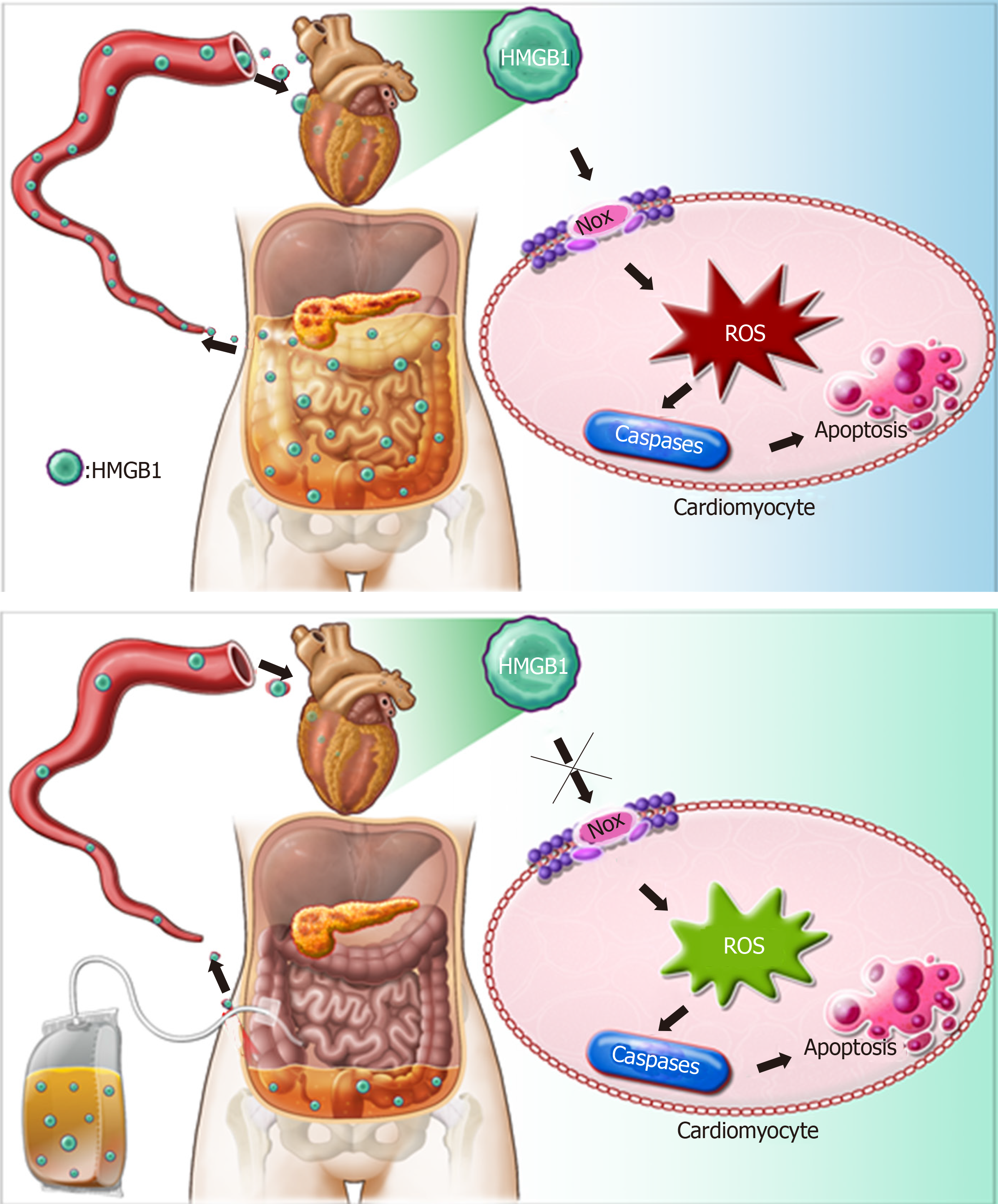

Based on the above findings, we propose a schematic diagram for the possible mechanism behind the effect of APD on SACI (Figure 8). Once SAP occurs, HMGB1 is mainly released from injured pancreas and peritoneal macrophages/monocytes. High levels of HMGB1 in the bloodstream can trigger a lethal inflammatory process and participate in the development of remote organ injury in SAP. Following APD treatment, the levels of HMGB1 in the circulation decreased significantly, resulting in inhibition of expression and activity of cardiac NOX, which can effectively alleviate apoptosis via downregulating ROS production and thereby protecting against SACI.

In the present study, we provided the first evidence that APD treatment exerts a beneficial effect on SACI. Our key findings were that: (1) APD treatment decreases the serum levels of cardiac enzymes and improves cardiac function; (2) APD treatment alleviates cardiac oxidative stress and accompanied cardiomyocyte apoptosis; and (3) the beneficial effects of APD treatment in ameliorating SACI are due to the inhibition of oxidative damage via downregulating HMGB1-mediated expression of NOX. Our data show that APD is a promising treatment in SACI.

SAP is a dangerous and lethal acute abdominal disease. PAAF is a common local complication and is important in the progression of systemic inflammatory response during SAP[28]. PAAF causes elevated intra-abdominal pressure and aggravates abdominal viscus injuries. Moreover, the toxic substances in PAAF can be reabsorbed into the circulation to amplify the systemic inflammatory response and induce distant organ injury[28]. Therefore, any strategies or methods to remove PAAF may be effective in treating SAP and its related complications. In our previous studies, we discovered that APD treatment exerts beneficial effects on patients or animals with SAP[7,10]. Our results demonstrated early APD could effectively relieve or control the severity of SAP without increase in infection rate, improve tolerance of enteral nutrition and reduce intra-abdominal pressure[9,29,30]. It was an important development and supplement for the minimally invasive step-up approach with important clinical implications.

SAP is usually complicated with multiple organ injury[31]. Cardiac injury is an important cardiovascular complication, and cardiac decompensation even causes death. In this study, we produced a well-characterized SAP-induced cardiac injury model by retrograde injection of 5% sodium taurocholate, as described previously with some modifications[25]. SAP was demonstrated by morphological changes, hemodynamic and echocardiographic abnormalities, elevated cardiac enzymes, increased LPO production and myocardial cell apoptosis. Unlike other system failures during SAP that have been extensively studied, cardiac injury and intervention for preservation of heart function have been less emphasized in the management of SAP. Thus, we assessed the effect of APD treatment on SAP-evoked myocardial injury and explored the potential mechanisms.

Through a series of animal experiments, we found that APD treatment markedly improved histopathological changes in the heart tissues and reversed the alterations in serum cardiac enzymes and cardiac dysfunction. The serum levels of lactate dehydrogenase, creatine kinase-MB and cardiac troponin-I in SAP rats were significantly decreased following APD treatment, indicating the cardioprotective effect of APD induced by SAP. In line with the above findings, morphological changes indicative of cardiac injury that occurs in SAP, including disruption of myocardial fibers, cellular edema and intensive infiltration, were markedly alleviated following APD treatment. Preserving near normal heart tissue architecture will yield beneficial effects to maintain near-normal heart function, which was reflected by near-normal hemodynamics and echocardiography in SAP rats receiving APD treatment. These results indicate the important contribution of APD treatment to myocardial injury in SAP models.

Oxidative stress is a key contributor to the initiation and progression of SAP-induced remote organ injury[32]. Oxidative stress is inseparable from abnormal activation of oxidases[33]. Recent studies have indicated that NOX makes a major contribution to ROS generation, mediates ROS in the heart and then increases in response to various stimuli[34]. The present study was prompted by our previous finding that NOX hyperactivity was present in the heart of SAP rats and could cause oxidative injury and increase myocardial cell apoptosis and that inhibition of NOX had a protective effect against cardiac injury induced by SAP[24]. We hypothesized that the cardioprotective effect of APD treatment was achieved through ameliorating oxidative injury via the modulation of NOX. When measurements were implemented at 24 h after SAP induction, treatment with APD significantly decreased protein expression and activity of NOX in the heart. This was supported by the decreased ROS production and LPO level and increase in SOD activity and GSH level in heart tissues in the APD-treated group. Furthermore, myocardial cell apoptosis secondary to oxidative stress that accounts for contractility declines was also observed in SAP rats at 24 h[35]. APD reduced the number of myocardial cell apoptosis and modulated the expression of apoptosis-related proteins. As shown in this study, the expression levels of proapoptotic markers, i.e. cleaved caspase-3 and Bax, were markedly decreased, whereas the expression of antiapoptotic marker Bcl-2 was increased in the heart tissues of SAP rats following APD treatment. These data demonstrated that APD treatment alleviated oxidative stress damage and myocardial cell apoptosis induced by SAP. However, it is unclear how the elimination of PAAF via APD treatment reduces cardiac NOX. A possible explanation is that APD decreases the levels of some lethal factors that can act on cardiac NOX.

Oxidative stress has a direct relationship with systemic inflammatory response during SAP[36], which may involve some proinflammatory cytokines. Recently, extracellular HMGB1 was identified as a novel proinflammatory cytokine, which could trigger a lethal inflammatory process and participate in the development of pancreatic and remote organ injury in SAP[12,14]. Accumulated evidence indicates that the level of serum HMGB1 is significantly elevated in patients with SAP and SAP-induced animal models and is positively related to the outcome of SAP as well as organ dysfunction[16,17]. Meanwhile, HMGB1 plays an important role in the pathogenesis of cardiac dysfunction in many diseases, such as ischemia-reperfusion injury, sepsis and diabetic cardiomyopathy[12,37,38]. Thus, increased HMGB1 may have a detrimental effect on the heart in SAP. In our present study, we found that serum levels of HMGB1 increased in SAP rats, and it was noteworthy that the level of HMGB1 in PAAF was higher than that in serum of the sham group. In light of the fact that the key feature of acute pancreatitis is damage to the pancreas, our results regarding the beneficial effects of APD on pancreatic injury were consistent with previous studies, suggesting that HMGB1 was first produced and released by the pancreas and peritoneal macrophages/monocytes in response to inflammatory mediators during SAP. As a treatment strategy to eliminate PAAF, APD not only improves pancreatic histopathology in SAP but also regulates the polarization of peritoneal macrophages[39]. Therefore, it is reasonable to conceive that APD could decrease HMGB1 level in the circulation. As our results showed, there was a significant decline in serum HMGB1 level following APD treatment in the sham group compared with the SAP group. In addition, active neutralization with anti-HMGB1 antibodies or HMGB1-specific blockage via box A could prevent cardiac dysfunction in mice with ischemia-reperfusion injury, sepsis and diabetic cardiomyopathy[18-20]. Taken together, these results imply that downregulated HMGB1 is involved in the beneficial effects of APD in SACI.

To confirm that the decreased level of serum HMGB1 induced by APD can alleviate the hyperactivity of cardiac NOX, we intraperitoneally injected PAAF, with or without anti-HMGB1 neutralizing antibody, into rats with cerulein-induced pancreatitis. Eight hours after PAAF injection, the circulating level of HMGB1 in the PI group was significantly increased compared with that in the control group, suggesting that HMGB1 in PAAF can enter the bloodstream in MAP. Correspondingly, mRNA expression of NOX2 and NOX4 and protein expression of NOX2 were significantly increased. When the dose of anti-HMGB1 neutralizing antibody increased up to 200 μg, we observed that NOX mRNA and NOX protein expression decreased more than in the PI group. The important findings were consistent with previous studies that HMGB1 increases ROS production through activation of NOX. However, HMGB1 acting on cells must pass through some membrane receptors, such as Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4, which is the first target activated by extracellular HMGB1 to induce deleterious effects and is highly expressed in the heart[40]. In addition, TLR4-NOX interaction is suggested to participate in the pathogenesis of myocardial injury by activating multiple signaling pathways. For example, LPS-induced cardiac dysfunction is regulated by autophagy and ROS production in cardiomyocytes via the TLR4-NOX4 pathway[41]. As for SAP, whether TLR4 is also involved in HMGB1-induced cardiac NOX hyperactivity is still unclear, and future studies should be carried out.

Our results reveal that APD treatment ameliorated myocardial injury and improved cardiac function in a rat model of SAP. The cardioprotective effects of APD treatment are potentially due to the inhibition of oxidative stress by downregulation of HMGB1-mediated expression of NOX. This study suggests a novel mechanism underlying the effect of APD on SAP and related complications.

Severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) is a fatal systemic disease usually complicated with multiple distant organ injury. Among the distant organ injury, SAP-associated cardiac injury (SACI) occurs in a variable proportion of patients, and cardiac decompensation even causes death. Despite constant understanding in the pathogenesis of SAP and significant improvement in clinical management, the mortality rate remains high and unacceptable. In our previous study, early abdominal paracentesis drainage (APD) was found to effectively relieve or control the severity of SAP and maintenance of organ function through removing pancreatitis associated ascitic fluids (PAAF). However, the effect of APD treatment on SAP-associated cardiac injury and the possible mechanism are yet to be elucidated.

Inflammatory mediators exert a vital role in the initiation and progression of SAP in the early stage. High concentration of high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) in the pancreatitis associated ascitic fluids has been confirmed. Thus, we want to further study whether HMGB1 in ascites is related to SAP-associated cardiac injury, which may be a novel mechanism behind the effectiveness of APD on SAP.

The aim of this study was to determine the protective effects of APD treatment on SAP-associated cardiac injury and explore the potential mechanism.

In the present study, SAP was induced by 5% sodium taurocholate retrograde injection in Sprague-Dawley rats. Mild acute pancreatitis was induced by six consecutively intraperitoneal injections of cerulein (20 μg/kg rat weight). APD was performed by inserting a drainage tube with a vacuum ball into the lower right abdomen of the rats immediately after SAP induction. Morphological staining, serum amylase and inflammatory mediators, serum and ascites HMGB1, cardiac-related enzymes indexes and cardiac function and oxidative stress markers were performed. Cardiomyocyte apoptosis was detected by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase (NOX) mRNA was identified by real-time polymerase chain reaction. Apoptosis-associated proteins and protein expression of NOX were measured by western blot.

APD notably improved pancreatic and cardiac morphological changes, attenuated the alterations in serum amylase, inflammatory mediators, cardiac enzymes and function, reactive oxygen species production and oxidative markers, alleviated myocardial cell apoptosis, reversed the expression of apoptosis-associated proteins, downregulated HMGB1 level in serum and inhibited NOX hyperactivity. Furthermore, the activation of cardiac NOX by pancreatitis associated ascitic fluids intraperitoneal injection was effectively inhibited by adding anti-HMGB1 neutralizing antibody in rats with mild acute pancreatitis.

APD treatment could exert cardioprotective effects on SAP-associated cardiac injury through suppressing HMGB1-mediated oxidative stress.

Our study provided new evidence of the efficacy and safety of APD treatment on SAP and revealed a novel mechanism behind the effectiveness of APD on SAP. However, in this study we still do not know how HMGB1 modulates NOX under SAP conditions. In the next experiments, we should detect the expression profile of HMGB1 receptor protein in the heart and utilize a special receptor protein knockout model to clarify the precise mechanisms.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Inal V, Teragawa H, Thandassery RB, Teragawa H S-Editor: Wang J L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Forsmark CE, Vege SS, Wilcox CM. Acute Pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1972-1981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 615] [Cited by in RCA: 555] [Article Influence: 61.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Agarwal N, Pitchumoni CS. Acute pancreatitis: a multisystem disease. Gastroenterologist. 1993;1:115-128. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Waldthaler A, Schütte K, Malfertheiner P. Causes and mechanisms in acute pancreatitis. Dig Dis. 2010;28:364-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yegneswaran B, Kostis JB, Pitchumoni CS. Cardiovascular manifestations of acute pancreatitis. J Crit Care. 2011;26:225.e11-225.e18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Saulea A, Costin S, Rotari V. Heart ultrastructure in experimental acute pancreatitis. Rom J Physiol. 1997;34:35-44. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Prasada R, Dhaka N, Bahl A, Yadav TD, Kochhar R. Prevalence of cardiovascular dysfunction and its association with outcome in patients with acute pancreatitis. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2018;37:113-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Liu WH, Ren LN, Chen T, Liu LY, Jiang JH, Wang T, Xu C, Yan HT, Zheng XB, Song FQ, Tang LJ. Abdominal paracentesis drainage ahead of percutaneous catheter drainage benefits patients attacked by acute pancreatitis with fluid collections: a retrospective clinical cohort study. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:109-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Liu WH, Wang T, Yan HT, Chen T, Xu C, Ye P, Zhang N, Liu ZC, Tang LJ. Predictors of percutaneous catheter drainage (PCD) after abdominal paracentesis drainage (APD) in patients with moderately severe or severe acute pancreatitis along with fluid collections. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0115348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Liu L, Yan H, Liu W, Cui J, Wang T, Dai R, Liang H, Luo H, Tang L. Abdominal Paracentesis Drainage Does Not Increase Infection in Severe Acute Pancreatitis: A Prospective Study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49:757-763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zhou J, Huang Z, Lin N, Liu W, Yang G, Wu D, Xiao H, Sun H, Tang L. Abdominal paracentesis drainage protects rats against severe acute pancreatitis-associated lung injury by reducing the mobilization of intestinal XDH/XOD. Free Radic Biol Med. 2016;99:374-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Deng C, Wang T, Cui J, Zhang S, Jiang Z, Yan H, Liang H, Tang L, Dai R. Effect of Early Abdominal Paracentesis Drainage on the Injury of Intestinal Mucosa and Intestinal Microcirculation in Severe Acute Pancreatitis Rats. Pancreas. 2019;48:e6-e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Erlandsson Harris H, Andersson U. Mini-review: The nuclear protein HMGB1 as a proinflammatory mediator. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:1503-1512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 288] [Cited by in RCA: 302] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ulloa L, Tracey KJ. The "cytokine profile": a code for sepsis. Trends Mol Med. 2005;11:56-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 304] [Cited by in RCA: 323] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Shen X, Li WQ. High-mobility group box 1 protein and its role in severe acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:1424-1435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yuan H, Jin X, Sun J, Li F, Feng Q, Zhang C, Cao Y, Wang Y. Protective effect of HMGB1 a box on organ injury of acute pancreatitis in mice. Pancreas. 2009;38:143-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yasuda T, Ueda T, Takeyama Y, Shinzeki M, Sawa H, Nakajima T, Ajiki T, Fujino Y, Suzuki Y, Kuroda Y. Significant increase of serum high-mobility group box chromosomal protein 1 levels in patients with severe acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2006;33:359-363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yasuda T, Ueda T, Shinzeki M, Sawa H, Nakajima T, Takeyama Y, Kuroda Y. Increase of high-mobility group box chromosomal protein 1 in blood and injured organs in experimental severe acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2007;34:487-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Xu H, Yao Y, Su Z, Yang Y, Kao R, Martin CM, Rui T. Endogenous HMGB1 contributes to ischemia-reperfusion-induced myocardial apoptosis by potentiating the effect of TNF-α/JNK. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;300:H913-H921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Qin S, Wang H, Yuan R, Li H, Ochani M, Ochani K, Rosas-Ballina M, Czura CJ, Huston JM, Miller E, Lin X, Sherry B, Kumar A, Larosa G, Newman W, Tracey KJ, Yang H. Role of HMGB1 in apoptosis-mediated sepsis lethality. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1637-1642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 284] [Cited by in RCA: 319] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Volz HC, Seidel C, Laohachewin D, Kaya Z, Müller OJ, Pleger ST, Lasitschka F, Bianchi ME, Remppis A, Bierhaus A, Katus HA, Andrassy M. HMGB1: the missing link between diabetes mellitus and heart failure. Basic Res Cardiol. 2010;105:805-820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Marciniak A, Walczyna B, Rajtar G, Marciniak S, Wojtak A, Lasiecka K. Tempol, a Membrane-Permeable Radical Scavenger, Exhibits Anti-Inflammatory and Cardioprotective Effects in the Cerulein-Induced Pancreatitis Rat Model. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:4139851. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Fan J, Li Y, Levy RM, Fan JJ, Hackam DJ, Vodovotz Y, Yang H, Tracey KJ, Billiar TR, Wilson MA. Hemorrhagic shock induces NAD(P)H oxidase activation in neutrophils: role of HMGB1-TLR4 signaling. J Immunol. 2007;178:6573-6580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 229] [Cited by in RCA: 238] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lassègue B, San Martín A, Griendling KK. Biochemistry, physiology, and pathophysiology of NADPH oxidases in the cardiovascular system. Circ Res. 2012;110:1364-1390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 644] [Cited by in RCA: 622] [Article Influence: 47.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wen Y, Liu R, Lin N, Luo H, Tang J, Huang Q, Sun H, Tang L. NADPH Oxidase Hyperactivity Contributes to Cardiac Dysfunction and Apoptosis in Rats with Severe Experimental Pancreatitis through ROS-Mediated MAPK Signaling Pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019:4578175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Chen GY, Dai RW, Luo H, Liu WH, Chen T, Lin N, Wang T, Luo GD, Tang LJ. Effect of percutaneous catheter drainage on pancreatic injury in rats with severe acute pancreatitis induced by sodium taurocholate. Pancreatology. 2015;15:71-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Laster SB, Ohnishi Y, Saffitz JE, Goldstein JA. Effects of reperfusion on ischemic right ventricular dysfunction. Disparate mechanisms of benefit related to duration of ischemia. Circulation. 1994;90:1398-1409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Schmidt J, Rattner DW, Lewandrowski K, Compton CC, Mandavilli U, Knoefel WT, Warshaw AL. A better model of acute pancreatitis for evaluating therapy. Ann Surg. 1992;215:44-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 546] [Cited by in RCA: 673] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Pérez S, Pereda J, Sabater L, Sastre J. Pancreatic ascites hemoglobin contributes to the systemic response in acute pancreatitis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;81:145-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Hongyin L, Zhu H, Tao W, Ning L, Weihui L, Jianfeng C, Hongtao Y, Lijun T. Abdominal paracentesis drainage improves tolerance of enteral nutrition in acute pancreatitis: a randomized controlled trial. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52:389-395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Wang T, Liu LY, Luo H, Dai RW, Liang HY, Chen T, Yan HT, Cui JF, Li NL, Yang W, Liu WH, Tang LJ. Intra-Abdominal Pressure Reduction After Percutaneous Catheter Drainage Is a Protective Factor for Severe Pancreatitis Patients With Sterile Fluid Collections. Pancreas. 2016;45:127-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Rau BM, Bothe A, Kron M, Beger HG. Role of early multisystem organ failure as major risk factor for pancreatic infections and death in severe acute pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1053-1061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Escobar J, Pereda J, Arduini A, Sandoval J, Moreno ML, Pérez S, Sabater L, Aparisi L, Cassinello N, Hidalgo J, Joosten LA, Vento M, López-Rodas G, Sastre J. Oxidative and nitrosative stress in acute pancreatitis. Modulation by pentoxifylline and oxypurinol. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83:122-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Guzik TJ, Sadowski J, Guzik B, Jopek A, Kapelak B, Przybylowski P, Wierzbicki K, Korbut R, Harrison DG, Channon KM. Coronary artery superoxide production and nox isoform expression in human coronary artery disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:333-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Seddon M, Looi YH, Shah AM. Oxidative stress and redox signalling in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Heart. 2007;93:903-907. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 330] [Cited by in RCA: 379] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Whelan RS, Kaplinskiy V, Kitsis RN. Cell death in the pathogenesis of heart disease: mechanisms and significance. Annu Rev Physiol. 2010;72:19-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 546] [Cited by in RCA: 558] [Article Influence: 37.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | López Martín A, Carrillo Alcaraz A. Oxidative stress and acute pancreatitis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2011;103:559-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Andrassy M, Volz HC, Igwe JC, Funke B, Eichberger SN, Kaya Z, Buss S, Autschbach F, Pleger ST, Lukic IK, Bea F, Hardt SE, Humpert PM, Bianchi ME, Mairbäurl H, Nawroth PP, Remppis A, Katus HA, Bierhaus A. High-mobility group box-1 in ischemia-reperfusion injury of the heart. Circulation. 2008;117:3216-3226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 465] [Cited by in RCA: 514] [Article Influence: 30.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Sundén-Cullberg J, Norrby-Teglund A, Rouhiainen A, Rauvala H, Herman G, Tracey KJ, Lee ML, Andersson J, Tokics L, Treutiger CJ. Persistent elevation of high mobility group box-1 protein (HMGB1) in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:564-573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 325] [Cited by in RCA: 352] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Liu RH, Wen Y, Sun HY, Liu CY, Zhang YF, Yang Y, Huang QL, Tang JJ, Huang CC, Tang LJ. Abdominal paracentesis drainage ameliorates severe acute pancreatitis in rats by regulating the polarization of peritoneal macrophages. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:5131-5143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 40. | Xu H, Su Z, Wu J, Yang M, Penninger JM, Martin CM, Kvietys PR, Rui T. The alarmin cytokine, high mobility group box 1, is produced by viable cardiomyocytes and mediates the lipopolysaccharide-induced myocardial dysfunction via a TLR4/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase gamma pathway. J Immunol. 2010;184:1492-1498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Zhao H, Zhang M, Zhou F, Cao W, Bi L, Xie Y, Yang Q, Wang S. Cinnamaldehyde ameliorates LPS-induced cardiac dysfunction via TLR4-NOX4 pathway: The regulation of autophagy and ROS production. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2016;101:11-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |