Published online Feb 28, 2019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i8.989

Peer-review started: December 11, 2018

First decision: January 23, 2019

Revised: January 30, 2019

Accepted: February 15, 2019

Article in press: February 16, 2019

Published online: February 28, 2019

Processing time: 78 Days and 14.1 Hours

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an uncommon inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). However, its incidence has recently increased in South Korea. Moreover, UC diagnoses are frequently delayed, and the relationship between diagnostic delay and UC prognosis has not been extensively studied in South Korean patients.

To identify meaningful diagnostic delay affecting UC prognosis and to evaluate risk factors associated with diagnostic delay in South Korean patients.

Medical records of 718 patients with UC who visited the outpatient clinic of six university hospitals in South Korea were reviewed; 167 cases were excluded because the first symptom date was unknown. We evaluated the relationship between the prognosis and a diagnostic delay of 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 mo by comparing the prognostic factors [anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α use, admission history due to acute flare-ups, frequent admission due to flare-ups, surgery associated with UC, and the clinical remission state at the latest follow-up] at each diagnostic interval.

The mean diagnostic interval was 223.3 ± 483.2 d (median, 69 d; 75th percentile, 195 d). Among the prognostic factors, anti-TNFα use was significantly increased after a diagnostic delay of 24 mo. Clinical risk factors predictive of a 24-mo diagnostic delay were age < 60 years at diagnosis [odd ratio (OR) = 14.778, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.731-126.121], smoking history (OR = 2.688, 95%CI: 1.239-5.747, P = 0.012), and misdiagnosis of hemorrhoids (OR = 11.066, 95%CI: 3.596-34.053). Anti-TNFα use was associated with extensive UC at diagnosis (OR = 3.768, 95%CI: 1.860-7.632) and 24-mo diagnostic delay (OR = 2.599, 95%CI: 1.006-4.916).

A diagnostic delay > 24 mo was associated with increased anti-TNFα use. Age < 60 years at diagnosis, smoking history, and misdiagnosis of hemorrhoids were risk factors for delayed diagnosis.

Core tip: We aimed to identify the diagnostic delay that affects the prognosis in Korean patients with ulcerative colitis. We found that the group with a ≥ 24-mo diagnostic delay had used anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha drugs more frequently than the group with a < 24-mo delay. We also found that additional risk factors for a 24-mo delay in diagnosis were age < 60 years, smoking history, and a misdiagnosis of hemorrhoids by a physician.

- Citation: Kang HS, Koo JS, Lee KM, Kim DB, Lee JM, Kim YJ, Yoon H, Jang HJ. Two-year delay in ulcerative colitis diagnosis is associated with anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha use. World J Gastroenterol 2019; 25(8): 989-1001

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v25/i8/989.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i8.989

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an uncommon inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). However, its incidence has recently increased in South Korea. UC is diagnosed by clinical, endoscopic, and histologic findings because there is no definite diagnosis index. Therefore, differentiating it from other diseases of the intestines, such as acute gastroenteritis or irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is often difficult, and its diagnosis is often delayed. It is unclear whether a diagnostic delay of IBD is clinically significant. Recent studies have shown that early control of IBD affects the quality of life and the disease course, including its prognosis[1-4].

Most studies of a diagnostic delay for IBD were focused on Crohn’s disease (CD), and although the duration of the delay was different, the need for surgery was closely related to the diagnostic delay of CD in both Western and Asian populations[5-9]. There have been reports of clinical factors involved in the diagnostic delay of UC, but there is a lack of information regarding whether this delay affects the prognosis and treatment of UC for Asian patients[9]. Some patients have had symptoms for a long period, but the correct diagnosis was not made because UC was mild or had an insidious onset. A few studies have focused on how various durations of diagnostic delay can affect the future treatment and prognosis of these patients. Diagnostic delay and its impact on Western and Asian populations may be significantly different due to genetic or environmental factors; therefore, it is necessary to examine the results according to countries or regions.

Thus, we aimed to identify the period of delay in diagnosis (time from the first symptoms to UC diagnosis) that affected treatment and prognosis. We also evaluated the risk factors and clinical significance of a diagnostic delay for UC in South Korean patients.

This retrospective study was based on patient data collected from six university-affiliated hospitals located in metropolitan areas (Incheon-si, Ansan-si, Anyang-si, Suwon-si, Sungnam-si and Dongtan-si) near Seoul, South Korea, from January 2006 to December 2016. We analyzed the medical records of 718 patients who visited the outpatient clinic in 2016, had a definite diagnosis of UC, and were followed up for more than 6 mo. The diagnosis of UC was based on clinical, radiological, endoscopic, and pathologic findings. One hundred sixty-seven patients were excluded from the study because of incomplete medical record data regarding the first day of symptoms. Patients were not required to provide informed consent for inclusion in this retrospective study. We anonymized all clinical data to protect personal information. This study was conducted with the approval of the ethics committee of Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital in Anyang, South Korea (IRB No. 2016-I607). The study was performed in accordance with the recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Demographic characteristics of patients at the time of the first diagnosis were collected, including sex, age, body mass index (BMI), family history of UC, history of smoking, residence at the time of diagnosis (urban or rural), and education level (university education or less). Clinical medical records regarding the first symptoms and endoscopic and laboratory findings were also investigated, such as the day when the first symptom occurred, the day of the first physician visit, the day of first diagnosis, the type of symptoms (hematochezia, chronic diarrhea, abdominal pain), cases misdiagnosed as other diseases (hemorrhoids, IBS), Mayo score including endoscopic score[10-12], disease extension (proctitis, left side, extensive)[13], and C-reactive protein level (CRP, mg/dL). During data collection, to determine the Mayo endoscopic score and the extension of the disease, endoscopy findings were reviewed again by the endoscopist from each medical center. To reduce inter-observer variation, all endoscopist reviewers were trained using the same reference material[10-13] before the review. The use of prescribed medications [oral/intravenous (IV) steroids, azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine (AZA/6MP), or anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (anti-TNFα)] and the first day of the prescribed medication were investigated. To determine the prognostic factors, the use of anti-TNFα, the hospital admission history due to acute flare-ups[14,15], frequent admission (more than two admissions due to UC flare-ups), surgery associated with UC, and the clinical remission state at the latest follow-up were obtained from the medical records. The diagnostic interval was defined as the time from the first symptom until UC diagnosis. We divided the patients into the early and delay groups according to several diagnostic interval criteria (3 mo, 6 mo, 12 mo, 18 mo and 24 mo. Then, we compared the two groups according to the aforementioned demographic and clinical characteristics to determine the diagnostic delay having a clinical impact.

Both categorical and continuous variables of baseline characteristics were analyzed. Continuous variables are shown as mean ± standard deviation or medians with ranges. To evaluate the criteria for a diagnostic delay having a clinical impact, the chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test, and Kaplan-Meier method with the log-rank test were used to compare prognostic factors between the early group and delay group. After the meaningful diagnostic delay and prognosis factors were determined, they were compared to the clinical factors (sex, age, BMI, first symptom, cases misdiagnosed as hemorrhoids or IBS, Mayo score, disease extension, and CRP level) by univariate analysis. Multivariate logistic regression analyses including significant clinical factors from the univariate analysis were performed to evaluate risk factor-related diagnostic delay and prognosis. Odd ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated as measures of the correlation between the clinical variables and outcomes of interest. P < 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States).

Clinical characteristics of the patients were as follows: male sex, 318 (55.7%); mean age at diagnosis, 40.56 ± 16.11 years; and BMI at diagnosis, 22.28 ± 3.19 kg/m2 (Table 1). Seventy-seven of 443 (17.4%) had a history of smoking. Presenting first symptoms were hematochezia (388/548; 70.8%), diarrhea (164/548; 29.9%), and abdominal pain (39/548; 7.1%). The days from first symptoms to UC diagnosis were 223.28 ± 483.15 (median, 69); 75% of patients were diagnosed within 195 d. Time from the first symptoms to the first hospital visit was 154.22 ± 379.140 d (median, 40 d), and the time from the first hospital visit to diagnosis was 69.06 ± 295.04 d (median, 9 d). The Mayo score at diagnosis was examined in 399 patients; 179 (44.9%) had mild disease, 204 (51.1%) had moderate disease, and 220 (4.0%) had severe disease. Disease extension at diagnosis was examined in 547 patients; 253 (46.3%) had proctitis, 160 (29.3%) had left-side colitis, and 134 (24.5%) had extensive colitis. Prescribed medications used by all patients were as follows: oral/IV steroids, 250 (45.4%); AZA/6MP, 163 (29.8%); and anti-TNFα, 50 (9.1%).

| Characteristics | Value |

| Male sex (%) | 318/551 (55.7) |

| Age at diagnosis, yr | 40.56 ± 16.11 |

| BMI at diagnosis, kg/m2 | 22.28 ± 3.19 |

| Family history of IBD (%) | 51/369 (13.8) |

| History of smoking (%) | 77/443 (17.4) |

| First symptom | |

| Hematochezia | 388/548 (70.8) |

| Diarrhea | 164/548 (29.9) |

| Abdominal pain | 39/548 (7.1) |

| Diagnostic interval, d (median) | 223.28 ± 483.15 (69) |

| Time from first symptom to hospital visit, d (median) | 154.22 ± 379.140 (40) |

| Time from first hospital visit to diagnosis, d (median) | 69.06 ± 295.04 (9) |

| Mayo score at diagnosis (%) | |

| Mild | 179/399 (44.9) |

| Moderate | 204/399 (51.1) |

| Severe | 220/399 (4.0) |

| Disease extent at diagnosis (%) | |

| Proctitis | 253/547 (46.3) |

| Left side | 160/547 (29.3) |

| Extensive | 134/547 (24.5) |

| Steroid (oral or intravenous) use (%) | 250/551 (45.4) |

| AZA/6MP use (%) | 163/551 (29.6) |

| Anti-TNFα use (%) | 50/551 (9.1) |

| Admission due to flare-up (%) | 121/430 (22.0) |

| Frequent admission due to flare-up (%) | 50/551 (9.1) |

| UC-related surgery (%) | 7/551 (1.3) |

| Clinical remission at the latest follow-up (%) | 333/467 (71.3) |

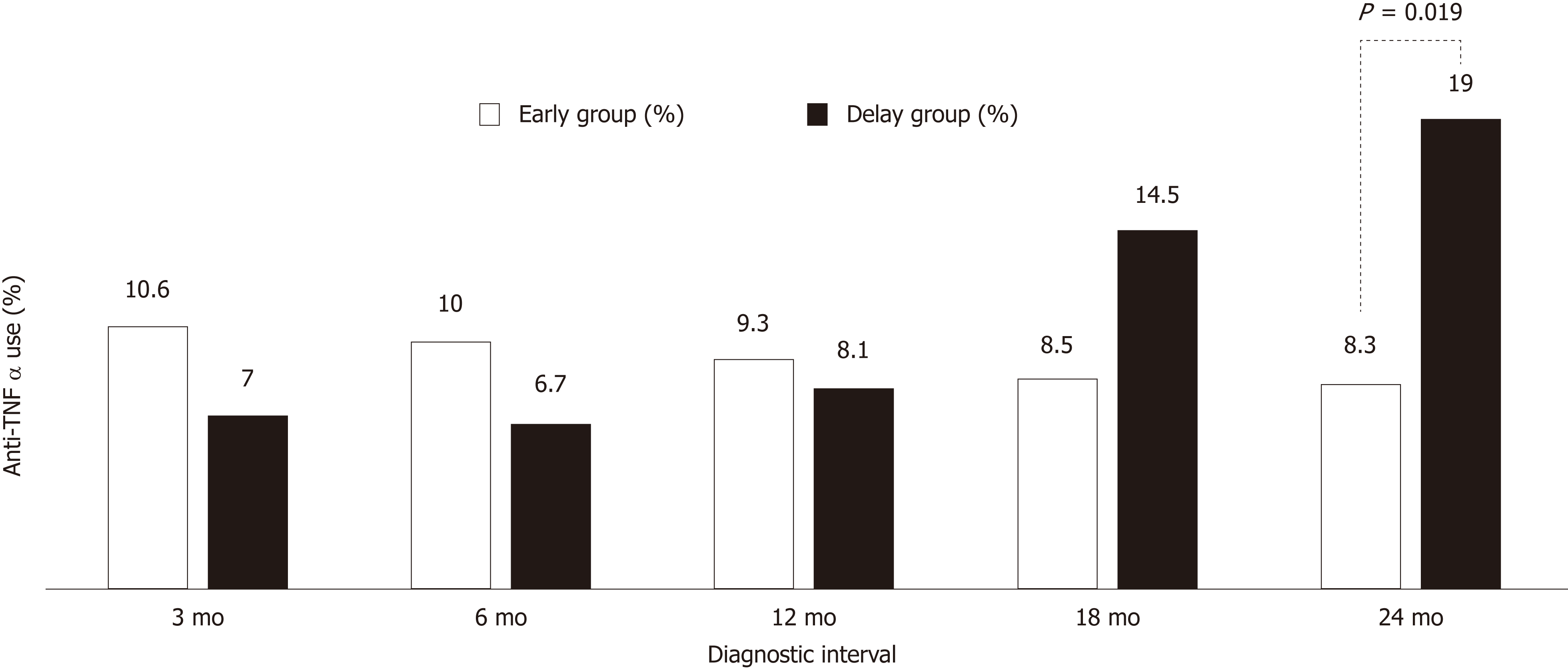

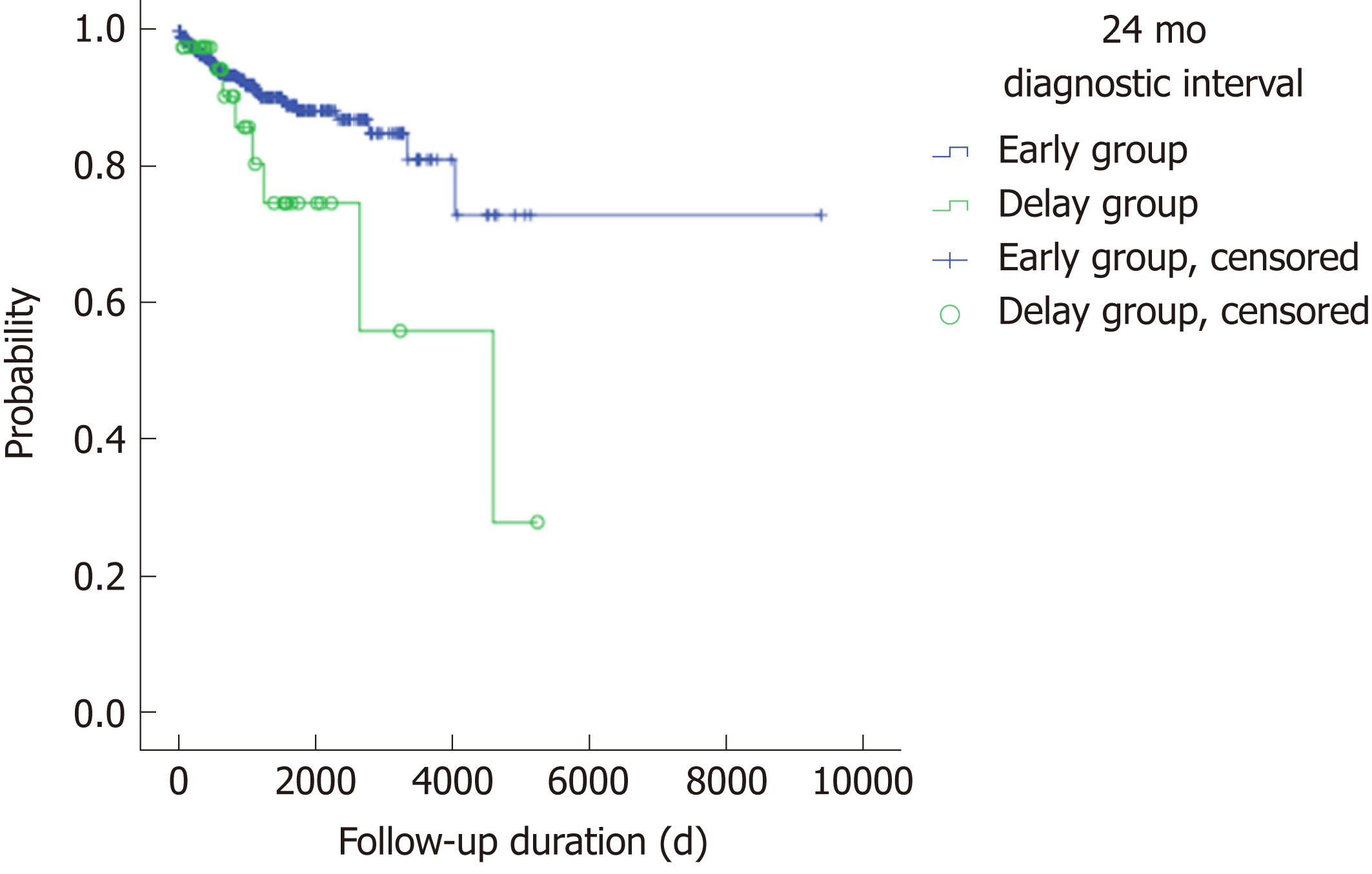

There were no statistically significant differences in the use of anti-TNFα, hospital admission history for acute flare-ups, frequent admission, surgery associated with UC, or clinical remission state at the latest follow-up between the early and delay groups with other diagnostic intervals (3, 6, 12 and 18 mo) (Table 2). In Figure 1, the use of anti-TNFα at the 3-mo diagnostic interval was insignificantly prevalent in the early group (34/322; 10.6%) and the delay group (16/229; 7.0%); however, the use of anti-TNFα by the early group and delay group began to decrease at the 18-mo diagnostic interval. Finally, at the 24-mo diagnostic interval, it was significantly higher in the delay group (8/42; 35.7%) than in the early group (42/509; 8.3%) (P = 0.019). Anti-TNFα free-survival rates between the early and delay groups according to the 24-mo diagnostic interval were significantly different (P = 0.034) (Figure 2). Therefore, it was determined that 24 mo was the diagnostic delay cutoff point for poor outcomes, and this delay was related to the use of anti-TNFα.

| Diag-nostic inter-val | 3 mo | 6 mo | 12 mo | 18 mo | 24 mo | ||||||||||

| Early group (%) | Delay group (%) | P value | Early group (%) | Delay group (%) | P value | Early group (%) | Delay group (%) | P value | Early group (%) | Delay group (%) | P value | Early group (%) | Delay group (%) | P value | |

| 322 | 229 | 401 | 150 | 452 | 99 | 496 | 55 | 509 | 42 | ||||||

| (58.4) | (41.6) | (72.8) | (27.2) | (82.0) | (18) | (90) | (10) | (92.4) | (7.6) | ||||||

| Anti-TNFα use | 0.150 | 0.249 | 0.847 | 0.137 | 0.019 | ||||||||||

| No | 288 | 213 | 361 | 140 | 410 | 91 | 454 | 47 | 467 | 34 | |||||

| (89.4) | (93.0) | (90.0) | (93.3) | (90.7) | (91.9) | (91.5) | (85.5) | (91.7) | (81.0) | ||||||

| Yes | 34 | 16 | 40 | 10 | 42 | 8 | 42 | 8 | 42 | 8 | |||||

| (10.6) | (7.0) | (10.0) | (6.7) | (9.3) | (8.1) | (8.5) | (14.5) | (8.3) | (19.0) | ||||||

| Admission (flare-up) | 0.269 | 0.203 | 1.000 | 0.509 | 0.703 | ||||||||||

| No | 246 | 184 | 307 | 123 | 353 | 77 | 389 | 41 | 398 | 32 | |||||

| (76.4) | (80.3) | (76.6) | (82.0) | (78.1) | (77.8) | (78.4) | (74.5) | (78.2) | (76.2) | ||||||

| Yes | 76 | 45 | 94 | 27 | 99 | 22 | 107 | 14 | 111 | 10 | |||||

| (23.6) | (19.7) | (23.4) | (18.0) | (21.9) | (22.2) | (21.8) | (25.5) | (21.8) | (23.8) | ||||||

| Frequent admission | 0.150 | 0.384 | 0.443 | 0.806 | 0.412 | ||||||||||

| No | 288 | 213 | 362 | 139 | 409 | 92 | 450 | 51 | 461 | 40 | |||||

| (89.4) | (93.0) | (90.3) | (92.7) | (90.5) | (92.9) | (90.7) | (92.7) | (90.6) | (95.2) | ||||||

| Yes | 34 | 16 | 39 | 11 | 43 | 7 | 46 | 4 | 48 | 2 | |||||

| (10.6) | (7.0) | (9.7) | (7.3) | (9.5) | (7.1) | (9.3) | (7.3) | (9.4) | (4.8) | ||||||

| Surgery-related UC | 0.457 | 0.092 | 0.114 | 0.523 | 0.428 | ||||||||||

| No | 319 | 225 | 398 | 146 | 448 | 96 | 490 | 54 | 503 | 41 | |||||

| (99.1) | (98.3) | (99.3) | (97.3) | (99.1) | (97.7) | (98.8) | (98.2) | (98.8) | (97.6) | ||||||

| Yes | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 1 | |||||

| (0.9) | (1.7) | (0.7) | (2.7) | (0.9) | (3.0) | (1.2) | (1.8) | (1.2) | (2.4) | ||||||

| Clinical remission | 0.866 | 0.842 | 0.509 | 0.679 | 0.338 | ||||||||||

| No | 191 | 142 | 97 | 37 | 267 | 66 | 300 | 33 | 310 | 23 | |||||

| (71.0) | (71.7) | (29.0) | (28.0) | (70.6) | (74.2) | (71.6) | (68.8) | (71.9) | (63.9) | ||||||

| Yes | 78 | 56 | 238 | 95 | 111 | 23 | 119 | 15 | 121 | 13 | |||||

| (29.0) | (28.3) | (71.0) | (72.0) | (29.4) | (25.8) | (28.4) | (31.3) | (28.1) | (36.1) | ||||||

According to the univariate analysis (Table 3), sex, age, BMI, education level, residence at the time of diagnosis, family history of IBD, and the first symptom were not different between the early and delay groups. However, age < 60 years (P = 0.020), history of smoking (P = 0.008), and misdiagnosis of hemorrhoids (P = 0.000) were significantly increased in the delay group. According to the multivariate logistic regression analysis, independent risk factors predictive of 24 mo as the cutoff were age < 60 years (OR = 14.778, 95%CI: 1.731-126.121, P = 0.014), smoking history (OR = 2.688, 95%CI: 1.239-5.747, P = 0.012), and misdiagnosis of hemorrhoids (OR = 11.066, 95%CI: 3.596-34.053, P = 0.000) (Table 4).

| Total | Early group (< 24 mo) | Delay group (≥ 24 mo) | P value | ||

| Sex (%) | 0.872 | ||||

| Male | 318 (57.7) | 293 (57.6) | 25 (59.5) | ||

| Female | 233 (42.3) | 216 (42.4) | 17 (40.5) | ||

| Age (%) | 40.56 ± 16.11 | 40.93 ± 16.20 | 41.21 ± 14.47 | 0.903 | |

| 0.020 | |||||

| ≥ 60 yr | 80 (14.5) | 79 (15.5) | 1 (2.4) | ||

| < 60 yr | 471 (85.5) | 430 (84.5) | 41 (97.6) | ||

| BMI (%) | 0.306 | ||||

| < 25 kg/m2 | 295 (83.3) | 268 (82.7) | 27 (90.0) | ||

| ≥ 25 kg/m2 | 59 (16.7) | 56 (17.3) | 3 (10.0) | ||

| Education (%) | 0.561 | ||||

| < University | 170 (56.5) | 152 (55.9) | 18 (62.1) | ||

| ≥ University | 131 (43.5) | 120 (44.1) | 11 (37.9) | ||

| Residence at diagnosis (%) | 0.498 | ||||

| Rural | 503 (94.2) | 466 (94.3) | 37 (92.5) | ||

| Urban | 31 (5.8) | 28 (5.7) | 3 (7.5) | ||

| Family history of IBD (%) | 0.782 | ||||

| No | 318 (86.2) | 291 (85.8) | 27 (90.0) | ||

| Yes | 51 (13.8) | 48 (14.2) | 3 (10.0) | ||

| Smoking (%) | 0.008 | ||||

| No | 366 (82.6) | 339 (84.1) | 27 (67.5) | ||

| Yes | 77 (17.4) | 64 (15.9) | 13 (32.5) | ||

| First symptom (%) | |||||

| 0.540 | |||||

| Hematochezia | No | 160 (29.2) | 146 (28.9) | 14 (33.3) | |

| Yes | 388 (70.8) | 360 (71.1) | 28 (66.7) | ||

| 0.229 | |||||

| Chronic diarrhea | No | 384 (70.1) | 358 (70.8) | 26 (61.9) | |

| Yes | 164 (29.9) | 148 (29.2) | 16 (38.1) | ||

| Diagnosis before UC | |||||

| 0.000 | |||||

| Hemorrhoids (%) | No | 487 (94.7) | 453 (95.8) | 34 (82.9) | |

| Yes | 27 (5.3) | 20 (4.2) | 7 (17.1) | ||

| 0.066 | |||||

| IBS (%) | No | 494 (96.1) | 457 (96.6) | 37 (90.2) | |

| Yes | 20 (3.9) | 16 (3.4) | 4 (9.8) | ||

| Mayo score at diagnosis (%) | 0.958 | ||||

| Mild | 179 (44.9) | 163 (44.9) | 16 (44.4) | ||

| Moderate + Severe | 220 (55.1) | 200 (55.1) | 20 (55.6) | ||

| Disease extent at diagnosis (%) | 0.914 | ||||

| Proctitis + left side | 413 (75.5)) | 381 (75.4) | 32 (76.2) | ||

| Extensive | 134 (24.5) | 124 (24.6) | 10 (23.8) |

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age (≥ 60 yr vs < 60 yr) | 7.533 (1.021-55.557) | 0.020 | 14.778 (1.731-126.121) | 0.014 |

| Smoking history (no vs yes) | 2.550 (1.249-5.206) | 0.008 | 2.688 (1.239-5.747) | 0.012 |

| Misdiagnosed as hemorrhoids (no vs yes) | 4.663 (1.842-11.803) | 0.000 | 11.066 (3.596-34.053) | 0.000 |

According to the univariate analysis (Table 5), sex, age, smoking history, BMI, CRP level at diagnosis, early steroid use within 2 mo of diagnosis, and early AZA/6MP use within 2 mo of diagnosis were not predictive factors for anti-TNFα use. However, moderate or severe Mayo score (P = 0.001), extensive disease (P = 0.000), and a diagnostic delay ≥ 24 mo (P = 0.019) were significantly increased in the delay group. According to the multivariate logistic regression analysis, independent risk factors predictive of anti-TNFα use were extensive disease (OR = 3.768, 95%CI: 1.860-7.632, P = 0.000) and a diagnostic delay of ≥ 24 mo (OR = 2.599, 95%CI: 1.006-4.916, P = 0.049) (Table 6).

| Total | Anti-TNFα No | Anti-TNFα Yes | P value | ||

| Sex (%) | 0.731 | ||||

| Male | 318 (57.7) | 288 (57.5) | 30 (60.0) | ||

| Female | 233 (42.3) | 213 (42.5) | 20 (40.0) | ||

| Age (%) | 40.56 ± 16.11 | 41.10 ± 16.76 | 38.36 ± 16.05 | 0.268 | |

| 0.913 | |||||

| < 60 yr | 278 (50.5) | 428 (85.4) | 43 (86.0) | ||

| ≥ 60 yr | 273 (49.5) | 73 (14.6) | 7 (14.0) | ||

| Smoking (%) | 0.422 | ||||

| No | 366 (82.6) | 329 (83.1) | 37 (78.7) | ||

| Yes | 77 (17.4) | 67 (16.9) | 10 (21.3) | ||

| BMI (%) | 0.667 | ||||

| < 25 kg/m2 | 295 (83.3) | 260 (83.6) | 35 (81.4) | ||

| ≥ 25 kg/m2 | 59 (16.7) | 51 (16.4) | 8 (18.6) | ||

| Mayo score at diagnosis (%) | 0.001 | ||||

| Mild | 179 (44.9) | 170 (47.6) | 9 (21.4) | ||

| Moderate + severe | 220 (55.1) | 187 (52.4) | 33 (78.6) | ||

| Disease extent at diagnosis (%) | 0.000 | ||||

| Proctitis + left side | 413 (75.5) | 394 (79.3) | 19 (38.0) | ||

| Extensive | 134 (24.5) | 103 (20.7) | 31 (62.0) | ||

| CRP level at diagnosis (%) | 0.536 | ||||

| < 5 mg/dL | 265 (79.3) | 17 (73.9) | 282 (79.0) | ||

| ≥ 5 mg/dL | 69 (20.7) | 6 (26.1) | 75 (21.0) | ||

| Steroid use after diagnosis | 0.269 | ||||

| < 2 mo | 116 (57.1) | 31 (66.0) | |||

| ≥ 2 mo | 87 (42.9) | 16 (34.0) | |||

| AZA/6MP use after diagnosis | 0.741 | ||||

| < 2 mo | 47 (29.2) | 37 (29.8) | 10 (27.0) | ||

| ≥ 2 mo | 114 (70.8) | 87 (70.2) | 27 (73.0) | ||

| Diagnostic delay (%) | 0.019 | ||||

| < 24 mo | 509 (92.4) | 467 (93.2) | 42 (84.0) | ||

| ≥ 24 mo | 42 (7.6) | 34 (6.8) | 8 (16.0) |

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Mayo score (mild vs moderate + severe). | 3.333 (1.550-7.169) | 0.002 | 2.168 (0.956-4.916) | 0.064 |

| Disease extent (proctitis + left side vs extensive) | 6.241 (3.388-11.496) | 0.000 | 3.768 (1.860-7.632) | 0.000 |

| Diagnostic delay (< 24 mo vs ≥ 24 mo) | 2.616 (1.138-6.014) | 0.019 | 2.599 (1.006-4.916) | 0.049 |

We found that the ≥ 24-mo diagnostic delay group used anti-TNFα drugs more frequently than the < 24-mo delay group. We also found that risk factors for the 24-mo delay were age < 60 years, smoking history, and misdiagnosis of hemorrhoids by a physician.

In general, CD is known to have a longer diagnostic delay than UC[4,7,9,16,17]. This is because the main symptom of CD is abdominal pain, and it is necessary to differentiate it from IBS. Furthermore, those with UC seem to visit the hospital earlier because it is related to hematochezia. In three studies on delayed diagnosis in UC, the median delays were 1, 3.1 and 4 mo. These studies categorized patients at the 76th to 100th percentiles into the delay group, and according to this, a diagnosis of more than 3, 10 and 12 mo were classified as delayed diagnosis; non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use, male sex, and age < 40 years were suggested as factors related to delayed diagnosis[4,7,16]. In our study, the median delay was 3.3 mo; 75% of patients were diagnosed within 6.5 mo, and 7.6% of patients had a diagnostic delay of more than 24 mo. Therefore, the median delay and the delay for 75% of patients were not significantly different from that of other studies. In most previous studies, the definition of a diagnostic delay for IBD was defined as more than the 76th to 100th percentile of patients without a correct diagnosis[4,7,8,18]. Our initial hypothesis was that the diagnostic delay for 76th to 100th percentile of patients (> 6.5 mo in our study) would be correlated with prognostic factors; however, we did not find any significant results. Therefore, unlike previous studies, we did not predetermine the criteria for diagnostic delay; instead, we tried to determine the diagnostic delay that affects the prognostic factors. As a result, we found that a diagnostic delay of more than 24 mo was related to the use of anti-TNFα.

Age < 60 years at diagnosis, smoking history, and misdiagnosis of hemorrhoids were risk factors for the 24-mo diagnostic delay in our study. It is well known that smoking is related to UC[17]; however, a person who smokes may not be interested in health or may not be able to seek medical care because of economic reasons[19], which may have affected our results. Contrary to previous studies, we found that factors other than smoking were related to UC. Some studies showed that age older than 40 years was correlated with diagnostic delay, whereas others showed the opposite[7,16]. In our study, age of 40 years or younger and age of 40 years or older were not risk factors for diagnostic delay; however, age < 60 years was a risk factor for diagnostic delay. Additionally, misdiagnoses as hemorrhoids were risk factors, which was contradictory to the finding of a Western study that showed UC was sometimes found faster by hematochezia[4]. There were several reasons for these results. First, regarding genetics, UC in Asian individuals, including South Koreans, may have a milder course than that in Western individuals, although the clinical features of both are similar[20-24]. Second, there are many regional differences in each country due to environmental factors such as medical accessibility and insurance status[25,26]. For example, in South Korea, colorectal cancer screening is performed after age 50 years, and hemorrhoids are common. Furthermore, recently, UC has been increasingly observed in Asian individuals compared to Western individuals. Therefore, because of environmental and genetic factors, our results may not be applicable to other populations. However, more research is necessary to determine whether our research represents the entire Asian population.

In the CD studies which examined the relation between diagnostic delay and prognosis, a delayed diagnosis of 13, 18, 25 and 34 mo was associated with CD-related surgery[5-8]. In a study of 1047 patients in South Korea, an 18-mo diagnostic delay was predictive of further development of intestinal stenosis, internal fistulas, and perianal fistulas[27]. Although the durations of the delays were different, the need for surgery was closely related to the diagnostic delay of CD in both Asian and Western populations. These studies indicated that as the duration of exposure to the disease increased, cumulative intestinal damage did not respond to medical treatment and the necessity for surgery increased. There are very few studies on the relationship between diagnostic delay and the prognosis of UC. A previous study performed in South Korea suggested that a diagnostic delay of 6.2 mo led to an increased risk for intestinal surgery[9]. Unfortunately, in our study, the number of surgeries (7/551; 1.3%) was too small, and the analysis was insufficient.

In our study, a 24-mo diagnostic delay was associated with the use of anti-TNFα drugs. In South Korea, certain factors regarding anti-TNFα use and surgery should be considered. First, a systemic analysis of IBD using population-based studies and randomized controlled trials suggested that anti-TNFα drugs had a protective effect against surgery in the biologic era, and that anti-TNFα drugs were used more frequently and earlier in South Korea[21,28]. Second, in Asia, the UC course is mild, patients resist surgery, and cases of colonic resection are rare[20-24]. In recent studies at an IBD specialized referral center in South Korea, the colectomy rate has decreased over the past 30 years for South Korean patients with UC[21]. In this study, 1119 patients were diagnosed between 2007 and 2013, the 7-year cumulative colectomy rate was 0.5% for patients diagnosed at this IBD referral hospital, and 4.7% for patients referred to this institution after diagnosis or treatment at another hospital. Therefore, because there is a possibility of a severe refractory cases in the referral population, the actual colectomy rate in South Korea is probably between 0.5% and 4.7% in biologic era, which is clearly lower than that of Western populations[29]. Third, practitioners in South Korea are unable to perform top-down treatment because of insurance problems; only patients who do not respond to steroids and AZT/6MP treatment can receive anti-TNFα treatment[30]. Thus, instead of surgery, the use of anti-TNFα drugs may be an important surrogate marker of the severity and prognosis of UC in South Korea.

The more extensive the disease, the longer the morbidity period; furthermore, primary sclerosing cholangitis and frequent admissions for flare-up were predictors of colonic resection of UC[31-33]. In addition, in a study of step-up treatment for UC, risk factors for anti-TNFα use were female sex, age > 40 years, extra-intestinal manifestation, and extensive disease[34]. In another study, extensive disease was also associated with anti-TNFα and AZA/6MP for UC[35]. Therefore, if the use of anti-TNFα replaces UC-related surgery as a prognostic factor, then extensive disease is an important factor in the prognosis of UC with a diagnostic delay, as indicated by our multivariate analysis. Unfortunately, several clinical factors such as early use of steroids, use of azathioprine, and Mayo scores were not associated with anti-TNFα use in our study.

There were some limitations to our study. First, it was a retrospective study; therefore, important clinical information, the first day of UC-related symptoms, may have been inaccurate because of recall bias. In addition, nearly one-fourth of patients were excluded from the study because of incomplete medical record data regarding the first day of symptoms. Second, NSAID use, oral contraceptive use, socioeconomic status, and EIM were not investigated. Third, the use of anti-TNFα drugs was greater in the early group than in the delay group when the diagnostic interval was 3 mo. This was presumably owing to the inclusion of patients with acute flare-ups; however, in our study, the diagnostic criteria for the acute flare-up group were not clear, hence this condition could not be ruled out. Nevertheless, this was the first multicenter study of the average diagnostic delay period for UC in the South Korean population. The prognosis was assessed according to the use of anti-TNFα in Asians avoiding surgery, and it was assumed that these patients could represent the Asian population with mild UC.

Our study suggested that a 24-mo diagnostic delay should be avoided in UC patients even those with mild UC symptoms. Care should be taken not to overlook UC in young patients with hemorrhoids who smoke.

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is diagnosed by clinical, endoscopic, and histologic findings because there is no definite diagnosis index. Therefore, differentiating it from other diseases of the intestines, such as acute gastroenteritis or irritable bowel syndrome is often difficult, and its diagnosis is often delayed. Recent studies have shown that early control of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) affects the quality of life and the disease course, including its prognosis.

Most studies of a diagnostic delay for IBD were focused on Crohn’s disease. There have been reports of clinical factors involved in the diagnostic delay of UC, but there is a lack of information regarding whether this delay affects the prognosis and treatment of UC. Diagnostic delay and its impact on Western and Asian populations may be significantly different owing to genetic or environmental factors; therefore, it is necessary to examine the results according to countries or regions.

We aimed to identify the delay in diagnosis (time from the first symptoms to UC diagnosis) that affected treatment and prognosis. We also evaluated the risk factors and clinical significance of a diagnostic delay for UC in South Korean patients.

This retrospective study was based on patient data collected from six university-affiliated hospitals located in South Korea from January 2006 to December 2016. We analyzed the medical records of 718 patients who visited the outpatient clinic in 2016, had a definite diagnosis of UC, and were available for follow-up for more than 6 mo. One hundred sixty-seven patients were excluded from the study because of incomplete medical record data regarding the first day of symptoms. To determine the prognostic factors, the use of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) drugs, the hospital admission history due to acute flare-ups, frequent admission, surgery associated with UC, and the clinical remission state at the latest follow-up were obtained from the medical records. The diagnostic interval was defined as the time from the first symptom until UC diagnosis. We divided the patients into the early and delay groups according to several diagnostic interval criteria (3 mo, 6 mo, 12 mo, 18 mo and 24 mo. Then, we compared the two groups according to the demographic and clinical characteristics to determine the diagnostic delay having a clinical impact.

The days from first symptoms to UC diagnosis were 223.28 ± 483.15 (median, 69); 75% of patients were diagnosed within 195 d. The use of anti-TNFα drugs at the 3-mo diagnostic interval was insignificantly prevalent in the early group (34/314; 10.6%) and the delay group (16/229; 7.0%); however, the use of anti-TNFα drugs by the early group and delay group started to decrease at the 18-mo diagnostic interval. Finally, at the 24-mo diagnostic interval, it was significantly higher in the delay group (8/42; 35.7%) than in the early group (42/509; 8.3%) (P = 0.019). Anti-TNFα free-survival rates between the early and delay groups according to the 24-mo diagnostic interval were significantly different (P = 0.034). Therefore, it was determined that 24 mo was the diagnostic delay cutoff point for poor outcomes. According to the multivariate logistic regression analysis, independent risk factors predictive of a diagnostic delay of 24 mo were age < 60 years [odd ratio (OR) = 14.778, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.731-126.121, P = 0.014], smoking history (OR = 2.688, 95%CI: 1.239-5.747, P = 0.012), and misdiagnosis of hemorrhoids (OR = 11.066, 95%CI: 3.596-34.053, P=0.000).

We found that the ≥ 24-mo diagnostic delay group more frequently used anti-TNFα compared to the < 24-mo delay group. We also found that risk factors for a 24-mo delay were age < 60 years, smoking history, and misdiagnosis of hemorrhoids by a physician.

Prospective studies are needed to reduce recall bias for important clinical studies such as the first day of UC-related symptoms.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Hosoe N S- Editor: Ma RY L- Editor: A E- Editor: Yin SY

| 1. | Markowitz J. Early inflammatory bowel disease: different treatment response to specific or all medications? Dig Dis. 2009;27:358-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Etchevers MJ, Aceituno M, Sans M. Are we giving azathioprine too late? The case for early immunomodulation in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:5512-5518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Ricart E, García-Bosch O, Ordás I, Panés J. Are we giving biologics too late? The case for early versus late use. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:5523-5527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Vavricka SR, Spigaglia SM, Rogler G, Pittet V, Michetti P, Felley C, Mottet C, Braegger CP, Rogler D, Straumann A, Bauerfeind P, Fried M, Schoepfer AM; Swiss IBD Cohort Study Group. Systematic evaluation of risk factors for diagnostic delay in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:496-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Schoepfer AM, Dehlavi MA, Fournier N, Safroneeva E, Straumann A, Pittet V, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Michetti P, Rogler G, Vavricka SR; IBD Cohort Study Group. Diagnostic delay in Crohn's disease is associated with a complicated disease course and increased operation rate. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1744-1753; quiz 1754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nahon S, Lahmek P, Paupard T, Lesgourgues B, Chaussade S, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Abitbol V. Diagnostic Delay Is Associated with a Greater Risk of Early Surgery in a French Cohort of Crohn's Disease Patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:3278-3284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zaharie R, Tantau A, Zaharie F, Tantau M, Gheorghe L, Gheorghe C, Gologan S, Cijevschi C, Trifan A, Dobru D, Goldis A, Constantinescu G, Iacob R, Diculescu M; IBDPROSPECT Study Group. Diagnostic Delay in Romanian Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Risk Factors and Impact on the Disease Course and Need for Surgery. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:306-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Li Y, Ren J, Wang G, Gu G, Wu X, Ren H, Hong Z, Hu D, Wu Q, Li G, Liu S, Anjum N, Li J. Diagnostic delay in Crohn's disease is associated with increased rate of abdominal surgery: A retrospective study in Chinese patients. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47:544-548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lee DW, Koo JS, Choe JW, Suh SJ, Kim SY, Hyun JJ, Jung SW, Jung YK, Yim HJ, Lee SW. Diagnostic delay in inflammatory bowel disease increases the risk of intestinal surgery. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:6474-6481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Stange EF, Travis SP, Vermeire S, Reinisch W, Geboes K, Barakauskiene A, Feakins R, Fléjou JF, Herfarth H, Hommes DW, Kupcinskas L, Lakatos PL, Mantzaris GJ, Schreiber S, Villanacci V, Warren BF; European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation (ECCO). European evidence-based Consensus on the diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis: Definitions and diagnosis. J Crohns Colitis. 2008;2:1-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 399] [Cited by in RCA: 372] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1625-1629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1958] [Cited by in RCA: 2244] [Article Influence: 59.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Hanauer SB, Lochs H, Löfberg R, Modigliani R, Present DH, Rutgeerts P, Schölmerich J, Stange EF, Sutherland LR. A review of activity indices and efficacy endpoints for clinical trials of medical therapy in adults with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:512-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 491] [Cited by in RCA: 504] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, Arnott ID, Bernstein CN, Brant SR, Caprilli R, Colombel JF, Gasche C, Geboes K, Jewell DP, Karban A, Loftus EV, Peña AS, Riddell RH, Sachar DB, Schreiber S, Steinhart AH, Targan SR, Vermeire S, Warren BF. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19 Suppl A:5A-36A. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Truelove SC, Witts LJ. Cortisone in ulcerative colitis; final report on a therapeutic trial. Br Med J. 1955;2:1041-1048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1832] [Cited by in RCA: 1863] [Article Influence: 26.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Choi CH, Moon W, Kim YS, Kim ES, Lee BI, Jung Y, Yoon YS, Lee H, Park DI, Han DS; IBD Study Group of the Korean Association for the Study of Intestinal Diseases. Second Korean guidelines for the management of ulcerative colitis. Intest Res. 2017;15:7-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Nguyen VQ, Jiang D, Hoffman SN, Guntaka S, Mays JL, Wang A, Gomes J, Sorrentino D. Impact of Diagnostic Delay and Associated Factors on Clinical Outcomes in a U.S. Inflammatory Bowel Disease Cohort. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:1825-1831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cantoro L, Di Sabatino A, Papi C, Margagnoni G, Ardizzone S, Giuffrida P, Giannarelli D, Massari A, Monterubbianesi R, Lenti MV, Corazza GR, Kohn A. The Time Course of Diagnostic Delay in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Over the Last Sixty Years: An Italian Multicentre Study. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:975-980. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Nahon S, Lahmek P, Lesgourgues B, Poupardin C, Chaussade S, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Abitbol V. Diagnostic delay in a French cohort of Crohn's disease patients. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:964-969. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Laaksonen M, Rahkonen O, Karvonen S, Lahelma E. Socioeconomic status and smoking: analysing inequalities with multiple indicators. Eur J Public Health. 2005;15:262-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kim YM, Park SH, Yang SK, Choe JW, Kim SH, Byeon JS, Myung SJ, Cho YK, Yu CS, Choi KS, Chung JW, Kim B, Choi KD, Kim JH. Clinical characteristics and long-term course of ulcerative colitis in Korea. Intest Res. 2006;4:12-21 Accessed June 30, 2006 Available from: https://www.irjournal.org/journal/view.php?number=406. |

| 21. | Lee HS, Park SH, Yang SK, Lee J, Soh JS, Lee S, Bae JH, Lee HJ, Yang DH, Kim KJ, Yea BD, Byeon JS, Myung SJ, Yoon YS, Yu CS, Kim JH. Long-term prognosis of ulcerative colitis and its temporal change between 1977 and 2013: a hospital-based cohort study from Korea. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:147-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lok KH, Hung HG, Ng CH, Kwong KC, Yip WM, Lau SF, Li KK, Li KF, Szeto ML. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of ulcerative colitis in Chinese population: experience from a single center in Hong Kong. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:406-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ling KL, Ooi CJ, Luman W, Cheong WK, Choen FS, Ng HS. Clinical characteristics of ulcerative colitis in Singapore, a multiracial city-state. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35:144-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kim ES, Kim WH. Inflammatory bowel disease in Korea: epidemiological, genomic, clinical, and therapeutic characteristics. Gut Liver. 2010;4:1-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sewell JL, Velayos FS. Systematic review: The role of race and socioeconomic factors on IBD healthcare delivery and effectiveness. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:627-643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Spivak W, Sockolow R, Rigas A. The relationship between insurance class and severity of presentation of inflammatory bowel disease in children. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:982-987. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Moon CM, Jung SA, Kim SE, Song HJ, Jung Y, Ye BD, Cheon JH, Kim YS, Kim YH, Kim JS, Han DS; CONNECT study group. Clinical Factors and Disease Course Related to Diagnostic Delay in Korean Crohn's Disease Patients: Results from the CONNECT Study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0144390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Olivera P, Spinelli A, Gower-Rousseau C, Danese S, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Surgical rates in the era of biological therapy: up, down or unchanged? Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2017;33:246-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Bernstein CN, Ng SC, Lakatos PL, Moum B, Loftus EV; Epidemiology and Natural History Task Force of the International Organization of the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. A review of mortality and surgery in ulcerative colitis: milestones of the seriousness of the disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:2001-2010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Yang SK. Personalizing IBD Therapy: The Asian Perspective. Dig Dis. 2016;34:165-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Targownik LE, Singh H, Nugent Z, Bernstein CN. The epidemiology of colectomy in ulcerative colitis: results from a population-based cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1228-1235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Chow DK, Leong RW, Tsoi KK, Ng SS, Leung WK, Wu JC, Wong VW, Chan FK, Sung JJ. Long-term follow-up of ulcerative colitis in the Chinese population. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:647-654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Falcone RA, Lewis LG, Warner BW. Predicting the need for colectomy in pediatric patients with ulcerative colitis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000;4:201-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Safroneeva E, Vavricka SR, Fournier N, Straumann A, Rogler G, Schoepfer AM. Prevalence and Risk Factors for Therapy Escalation in Ulcerative Colitis in the Swiss IBD Cohort Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:1348-1358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Ott C, Takses A, Obermeier F, Schnoy E, Salzberger B, Müller M. How fast up the ladder? Factors associated with immunosuppressive or anti-TNF therapies in IBD patients at early stages: results from a population-based cohort. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29:1329-1338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |