Published online Feb 28, 2019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i8.1002

Peer-review started: December 6, 2018

First decision: January 6, 2019

Revised: January 11, 2019

Accepted: January 18, 2019

Article in press: January 18, 2019

Published online: February 28, 2019

Processing time: 83 Days and 21.4 Hours

A clinical pathway (CP) is a standardized approach for disease management. However, big data-based evidence is rarely involved in CP for related common bile duct (CBD) stones, let alone outcome comparisons before and after CP implementation.

To investigate the value of CP implementation in patients with CBD stones undergoing endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).

This retrospective study was conducted at Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital in patients with CBD stones undergoing ERCP from January 2007 to December 2017. The data and outcomes were compared by using univariate and multivariable regression/linear models between the patients who received conventional care (non-pathway group, n = 467) and CP care (pathway group, n = 2196).

At baseline, the main differences observed between the two groups were the percentage of patients with multiple stones (P < 0.001) and incidence of cholangitis complication (P < 0.05). The percentage of antibiotic use and complications in the CP group were significantly less than those in the non-pathway group [adjusted odds ratio (OR) = 0.72, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.55-0.93, P = 0.012, adjusted OR = 0.44, 95%CI: 0.33-0.59, P < 0.001, respectively]. Patients spent lower costs on hospitalization, operation, nursing, medication, and medical consumable materials (P < 0.001 for all), and even experienced shorter length of hospital stay (LOHS) (P < 0.001) after the CP implementation. No significant differences in clinical outcomes, readmission rate, or secondary surgery rate were presented between the patients in the non-pathway and CP groups.

Implementing a CP for patients with CBD stones is a safe mode to reduce the LOHS, hospital costs, antibiotic use, and complication rate.

Core tip: We utilized a big-data process and application platform for exploring the value of clinical pathway (CP) implementation in patients with common bile duct stones undergoing endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Univariate and multivariable regression/linear models were developed to compare the outcomes between the patients in the non-pathway and CP groups. Our findings demonstrated that a CP is a safe mode to reduce the length of hospital stay, hospital costs, antibiotic use, and complication rate. The present study provides big-data evidence for clinical standardization of CPs.

- Citation: Zhang W, Wang BY, Du XY, Fang WW, Wu H, Wang L, Zhuge YZ, Zou XP. Big-data analysis: A clinical pathway on endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for common bile duct stones. World J Gastroenterol 2019; 25(8): 1002-1011

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v25/i8/1002.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i8.1002

Gallstone disease is one of the most frequent biliary diseases leading to hospita-lization and imposing a significant financial burden. The worldwide prevalence of gallstones presents a rising tendency due to the change of dietary structure and routine living customs in recent years[1,2]. Of the patients who suffered from gallstones, approximately 10%-15% were found to have synchronous common bile duct (CBD) stones[3,4]. The clinical manifestations of CBD stones are varied from biliary colic to a combination of complications, such as acute pancreatitis or cholangitis; sometimes, CBD stones even may be asymptomatic[5]. Treatment and management of CBD stones have changed considerably during the last three decades. With the popularization of minimally invasive surgery in clinical practice, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopan-creatography (ERCP) is currently recognized as a standard therapy for patients with CBD stones[6,7]. Despite this, a risk of complications after ERCP cannot be avoided, and it is even associated with increased morbidity and mortality[8]. In addition, there is evidence showing that in some patients with gallstones received ERCP and routine care at first admission, re-admission and longer preoperative stay were caused[9]. Due to the growing complexity of CBD stone treatments and care, it is crucial to develop a standardized multidisciplinary approach to avoid chaotic management of this disease.

A clinical pathway (CP) is an advanced medical diagnosis, treatment, and management mode, which may optimize medical treatment by facilitating clinical assessments, improving utilization efficiency of medical sources, and reducing economical expenses[10-12]. Nowadays, a CP is thought to be an effective tool to be explicit about the sequencing, timing and provision of interventions in clinical practice and can guide physicians and nursing staff in providing evidence-based results[13,14]. Moreover, analysis of evaluating indexes (including clinical outcome, efficiency indicators, financial indicators, and antibiotic use indicators) can guarantee the effectiveness of the CP implementation and optimization[15,16]. One study has demonstrated that a CP presents sustainable effects in gallstone-related care, resulting in shorter length of hospital stay (LOHS) and lower hospital expenses[9]. In addition, several studies conducted in other surgical domains also presented similar results[17-19]. However, implementation of the CP in China is in its start-up stage, especially in the field of hepatobiliary surgery. The status and value of the CP in the management of patients with CBD stones after ERCP remain to be explored. Given this concern, a retrospective study based on a big-data, intelligence database platform was launched. The aim of the present study was to analyze the impact of a CP on LOHS, readmission, treatment outcomes, hospital costs, and postoperative complication rate in patients with CBD stones undergoing ERCP.

This is a retrospective study of patients with CBD stones who received ERCP at Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital (Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China) between January 2007 and December 2017. This study was approved by Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Drum Tower Hospital of Nanjing University Medical School (201817001), and informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

All patients aged above 18 years old without previous ERCP history were included in this study. The exclusion criteria were: (1) Patients with previous or present hepatolithiasis; (2) patients with severe liver diseases, cardio-pulmonary or renal inadequacy; (3) patients with severe hematologic diseases and concomitant obvious coagulopathy; (4) patients with combined gallbladder, CBD, duodenal papillary neoplasm, or congenital choledochal cyst; (5) patients who underwent Billroth I and II gastrectomy or gastrojejunostomy; and (6) pregnant patients. Subjects who met criteria for this study were extracted automatically from a big-data, intelligence database platform (Yidu Cloud Technology Co. Ltd., Beijing, China) by setting the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The study population consisted of two groups which accepted conventional care (non-pathway group) and a CP (CP group), respectively.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of subjects were obtained from electronic medical records. Outcomes of pathway complementation were compared between the two groups in LOHS (total and preoperative LOHS), readmission rate (a second hospital admission within 30 d due to CBD stones and postoperative complications), treatment outcomes, hospital charges (also including medication, operation, perioperative examinations, nursing and medical consumable materials charges), antibiotic use, secondary surgery rate, and postoperative complications.

A set of sophisticated CPs for patients with CBD stones was implemented at this hospital in 2012. Development and optimization of the CP involved a multidisciplinary team under the instruction of relevant guidelines, including attending surgeons and residents, an anesthesiologist, a head of pharmacy faculty, and representatives from nursing and rehabilitation department. The training of the CP was performed before implementation to relevant personnel. Pathway I was designed for patients with expected LOHS less than 5-10 d, while pathway II was used for LOHS of 7-10 d. These CPs were explicit about the sequence of strategies for diagnosis, treatment, medication, routine care, and assessment. The pathway I is shown as an example in Appendix 1.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States). Data following a normal distribution are presented by mean ± standard deviation (mean ± SD), and otherwise are presented as median (interquartile range). Differences between the two groups were compared using Wilcoxon signed-rank test (continuous variables) or chi-squared test (categorical variables). In addition, univariable logistic regression models were used to determine whether odds of outcomes differed between the groups. We also utilized multivariable logistic (linear) regression models for evaluating the effect of pathway complementation on each outcome by controlling age, gender, smoking and drinking habits, the number of stones, and white blood cell (WBC) count at hospital admission. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

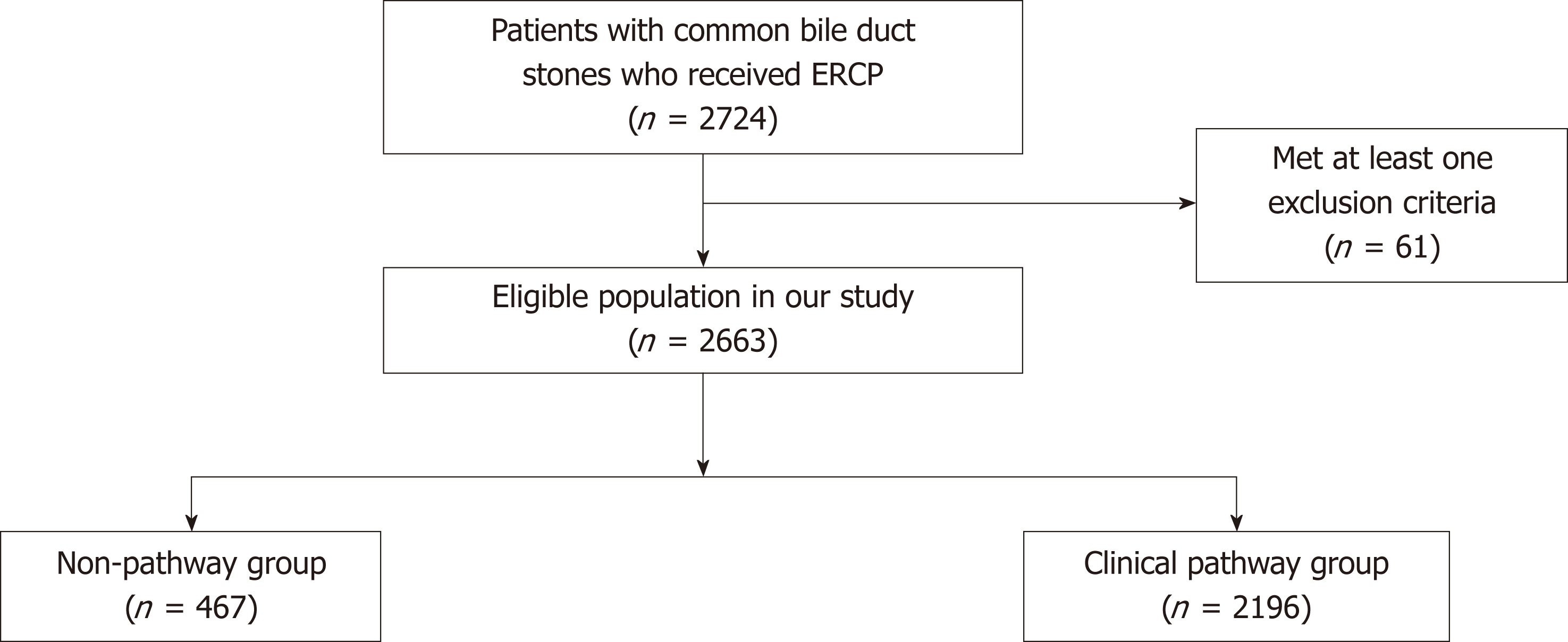

Two thousand six hundred and sixty-three eligible patients were included finally, of whom 467 were in the non-pathway group and 2196 in the clinical-pathway group (Figure 1). Table 1 shows the comparison of demographic and clinical characteristics between the patients who received routine care and CP care. There were no differences between the two groups in terms of age, gender, insured status, health behaviors, or maximum diameter of stones. The percentage of patients with multiple stones was found to be significantly different between the two groups (P < 0.001). The number of patients suffering from comorbidities was similar, although the percentage of patients with cholangitis was higher in the non-pathway group (P = 0.041). Although WBC counts in both groups were within the normal range, there was a significantly higher WBC count among the patients in the non-pathway group (P = 0.005).

| Characteristic | Non-pathway group (n = 467) | Cinical pathway group (n = 2196) | P value |

| Age, yr (median, range) | 64 (52-75) | 63 (51-75) | 0.405 |

| Female, n (%) | 235 (50.32) | 1093 (49.77) | 0.829 |

| Medical insurance, n (%) | 217 (46.47) | 945 (43.03) | 0.174 |

| Health behavior, n (%) | |||

| Smoking | 57 (12.21) | 260 (11.84) | 0.825 |

| Alcohol use | 36 (7.71) | 164 (7.47) | 0.858 |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 155 (33.19) | 703 (32.01) | 0.621 |

| Diabetes | 68 (14.56) | 292 (13.30) | 0.468 |

| COPD | 11 (2.36) | 54 (2.46) | 0.895 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0 | 6 (0.27) | 0.258 |

| Cholangitis | 74 (15.85) | 271 (12.34) | 0.041a |

| Cholecystolithiasis | 188 (40.26) | 780 (35.52) | 0.053 |

| JPD | 1 (0.21) | 10 (0.46) | 0.460 |

| CBD stone number ≥ 5, n (%) | 201 (43.04) | 1173 (53.42) | < 0.001a |

| Maximum diameter of stones, cm (median, range) | 0.8 (0.6-1.2) | 0.9 (0.6-1.2) | 0.949 |

| Laboratory test (median, range) | |||

| Temperature (°C), n = 359/2113 | 36.5 (36.3-36.8) | 36.5 (36.3-36.8) | 0.855 |

| WBC count, n = 370/1451 | 6.0 (4.7-9.2) | 5.7 (4.6-7.6) | 0.005a |

| Direct bilirubin level, n = 363/1439 | 12.2 (5.6-44.2) | 10.7 (4.8-37.2) | 0.210 |

| Total bilirubin level, n = 363/1439 | 22.6 (12.7-57.6) | 21.2 (12.5-51.9) | 0.628 |

| AST, n = 363/1440 | 47.9 (22.8-104.5) | 45.4 (23.5-104.8) | 0.842 |

| GGT, n = 363/1439 | 257.4 (115.3-492.4) | 265.1 (109.9-519.4) | 0.918 |

| ALP, n = 363/1439 | 161.7 (99.9-283.3) | 154.9 (97.4-259.3) | 0.536 |

| ALT, n = 364/1443 | 85.1 (29.6-203.2) | 89.0 (32.0-206.9) | 0.946 |

| Cr, n = 361/1431 | 62.0 (52.0-74.0) | 62.0 (2.0-73.0) | 0.966 |

Table 2 presents the outcomes of efficiency, treatment, hospital costs, and antibiotic use following the CP implementation. The median total LOHS was 8 (range, 6-11) d in the non-pathway group, while it was one day shorter (7, 5-9) in the CP group (P < 0.001). The pre-operative LOHS was found to be similar between the two groups. There were no significant changes with respect to the treatment outcomes (recovered, improved, not improved, and died) in both groups, and even no patients died in our study. Thirty-four (7.28%) patients in the non-pathway group required readmission to hospital, while readmission rate (173, 7.88%) was increased after pathway complementation, although this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.661). A considerably decreasing trend in the costs was observed among patients with the CP implementation, including hospitalization, medication, operation, nursing, materials, and preoperative examination (P < 0.001). In addition, implementation of the CP was associated with a reduced proportion of antibiotic use (P < 0.001). The median time of antibiotic use [11 (7.0-17.0) d] in the CP group was one day shorter than that before the CP complementation [12 (8.0-18.5) d] (P = 0.004). For patients in the CP group, secondary procedure occurred more frequently, although this difference was not statistically significant (16.94 vs 14.78%, P = 0.253).

| Characteristic | Non-pathway group (n = 467) | Cinical pathway group (n = 2196) | P value |

| Length of total hospital stay (median, range) | 8 (6-11) | 7 (5-9) | < 0.001a |

| Pre-operative length of stay | 2 (1-4) | 2 (1-3) | 0.451 |

| Readmission, n (%) | 34 (7.28) | 173 (7.88) | 0.661 |

| Clinical outcomes, n (%) | 0.115 | ||

| Recovered | 223 (47.75) | 1146 (52.19) | |

| Improved | 236 (50.54) | 1028 (46.81) | |

| Not improved | 8 (1.71) | 22 (1) | |

| Died | 0 | 0 | |

| Charges of hospitalization (CNY), (median, range) n = 467/2183 | 21508.3 (17150.6-30045.8) | 18362.9 (15665.8-22895.2) | < 0.001a |

| Charges of medication, n = 459/2153 | 6620.6 (3429.4-12239.7) | 4900.6 (3172.4-8186.0) | < 0.001a |

| Charges of operation, n = 458/2151 | 5741.0 (4519.2-7324.0) | 5455.2 (2670.0-6964.0) | < 0.001a |

| Charges of nursing, n = 454/2133 | 188.0 (115.0-288.0) | 120.0 (74.0-211.0) | < 0.001a |

| Charges of materials, n = 409/1540 | 7916.4 (6696.0-10552.6) | 6985.5 (6135.1-8224.7) | < 0.001a |

| Charges of examination, n = 459/2153 | 2698.0 (2224.5-3799.5) | 2463.5 (2134.5-3105.5) | < 0.001a |

| Antibiotic use, n (%) | 260/430 (60.47) | 832/1737 (47.90) | < 0.001a |

| Antibiotic usage duration (d) (median, range), n = 260/832 | 12 (8.0-18.5) | 11 (7.0-17.0) | 0.004a |

| Three line antibiotic use, n (%) | 51/430 (11.86) | 149/1737 (8.58) | 0.035a |

| Secondary surgery, n (%) | 69 (14.78) | 372 (16.94) | 0.253 |

The postoperative complication rates are compared in Table 3. About 26.77% of patients with routine care had at least one complication, while the incidence of complications dropped to 14.39% after the CP complementation (P < 0.001). The incidence rates of acute pancreatitis and liver abscess were considerably lower in patients after CP implementation, with significant differences between the two groups (P < 0.001).

| Characteristic | Non-pathway group (n = 467) | Cinical pathway group (n = 2196) | P value |

| Total, n (%) | 125 (26.77) | 316 (14.39) | < 0.001a |

| Acute pancreatitis | 113 (24.20) | 298 (13.57) | < 0.001a |

| Gallbladder perforation | 1 (0.21) | 1 (0.05) | 0.227 |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 0 | 2 (0.09) | 0.514 |

| Biliary tract infection | 2 (0.43) | 4 (0.18) | 0.308 |

| Liver abscess | 10 (2.14) | 11 (0.50) | < 0.001a |

The effect of the CP complementation on each outcome was also assessed by univariate and multivariate logistic regression through controlling age, gender, smoking and drinking habits, the number of stones, and WBC count at hospital admission (Tables 4 and 5). After adjusting for differences between the two groups, antibiotic use and postoperative complications were less in patients with the CP complementation [odds ratio (OR) = 0.72, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.55-0.93, P = 0.012; and OR = 0.44, 95%CI 0.33-0.59, P < 0.001, respectively]. The costs of hospitalization, operation, nursing, medication, and materials (P < 0.001 for all) and LOHS (P < 0.001) decreased significantly after implementation of the CP.

| Characteristic | Non-pathway group (n = 467) | Cinical pathway group (n = 2196) | OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Length of total hospital stay (median, range) | 8 (6-11) | 7 (5-9) | < 0.001a | ||

| Pre-operative length of stay | 2 (1-4) | 2 (1-3) | 0.078 | ||

| Readmission, n (%) | 34 (7.28) | 173 (7.88) | 1.09 (0.74, 1.60) | 0.661 | |

| Clinical outcomes, n (%) | 1.21 (0.99, 1.47) | 0.064 | |||

| Charges of hospitalization (CNY) (median, range) | 21508.3 (17150.6-30045.8) | 18362.9 (15665.8-22895.2) | < 0.001a | ||

| Medication | 6620.6 (3429.4-12239.7) | 4900.6 (3172.4-8186.0) | < 0.001a | ||

| Operating | 5741.0 (4519.2-7324.0) | 5455.2 (2670.0-6964.0) | < 0.001a | ||

| Nursing | 188.0 (115.0-288.0) | 120.0 (74.0-211.0) | < 0.001a | ||

| Materials | 7916.4 (6696.0-10552.6) | 6985.5 (6135.1-8224.7) | < 0.001a | ||

| Examination | 2698.0 (2224.5-3799.5) | 2463.5 (2134.5-3105.5) | < 0.001a | ||

| Antibiotic use, n (%) | 260/430 (60.47) | 832/1737(47.90) | 0.60 (0.49, 0.75) | < 0.001a | |

| Antibiotic usage duration (d) (median, range) | 12 (8.0-18.5) | 11 (7.0-17.0) | 0.310 | ||

| Three line antibiotic use, n (%) | 51/430 (11.86) | 149/1437 (8.58) | 0.69 | 0.036a | |

| Secondary surgery, n (%) | 69 (14.78) | 372 (16.94) | 1.18 | 0.254 | |

| Complications | 125 (26.77) | 316 (14.39) | 0.46 (0.36, 0.58) | < 0.001a | |

| Characteristic | Adjusted OR (95%CI) or coefficients | P value |

| Length of total hospital stay | -1.71 (-2.30, -1.12)1 | < 0.001a |

| Hospitalization costs | -5572.26 (-6931.48, -4213.03)1 | < 0.001a |

| Medication costs | -2760.03 (-3738.96, -1781.11)1 | < 0.001a |

| Operating costs | -382.08 (-635.30, -128.85)1 | < 0.001a |

| Nursing costs | -138.25 (-195.83, -80.66)1 | < 0.001a |

| Materials costs | -1688.35 (-2049.61, -1327.10)1 | < 0.001a |

| Examination costs | -138.25 (-195.83, -80.66)1 | < 0.001a |

| Three line antibiotic use | 0.89 (0.60, 1.31) | 0.546 |

| Antibiotic use, n (%) | 0.72 (0.55, 0.93) | 0.012a |

| Complications | 0.44 (0.33, 0.59) | < 0.001a |

Despite wide adoption of CPs throughout different departments currently, their evaluation and optimization remain doubtful[20]. The purpose of this study was to compare the indicators of CP implementation in five domains (clinical outcome, efficiency indicators, financial indicators, and antibiotic use indicators) for patients with CBD stones undergoing ERCP. Our results confirmed that pathway implementation in CBD stones was associated with reduced total LOHS, costs, antibiotic use, antibiotic use duration, and complication rate. More importantly, the decrease has not been achieved at the expense of increased readmission rate or mortality.

With the development of endoscopic technique, ERCP is considered a preferred therapeutic method in management of CBD stones. However, it can be still challenging in some cases, such as high total hospital expenses and high risk of post-ERCP complications[21,22]. CP, one of the main modes to standardize treatment and care, is increasingly adopted by hospitals to strive to better outcomes and lower costs. However, the definition of CP has not yet been fully elucidated in clinical practice, and the impact of pathway complementation is varied by different factors and conditions[23,24]. Findings of our study are consistent with those obtained by Kristin et al who demonstrated a considerable reduction in terms of costs and LOHS in patients with complicated gallstone disease after the CP implementation[9]. More recent studies showed similar improvements in other specialties of diseases, such as acute pancreatitis[25], breast cancer[15], and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease[26]. However, pre-operative length of stay showed no distinct disparity in our study, and the implementation of pathway might have greater impact on postoperative hospital stay. Similar to our results in terms of antibiotic use, Dona et al[27] reported that there was a reduction of antibiotic prescriptions in patients with community-acquired pneumonia after introducing a CP. Our study provided further evidence that the CP implementation can also significantly reduce the duration of antibiotic use and three-line antibiotic prescriptions. Thus, it is possible to conclude that a marked reduction of costs appears to be associated with several factors, such as effective pre-operative examination and rational use of medications and materials. Moreover, CP seems to be one of key approaches to maximize cost-effectiveness, while without sacrificing good treatment outcomes[28]. The most common causes of dropout from CP were postoperative complications that needed additional treatment. The findings of the present study demonstrated that rates of complications were lower in patients operated upon admission who implemented the CP compared to patients receiving routine care. There have been multiple previous publications in various domains which have demonstrated the lower incidence of complications following critical pathways[29-31]. However, critical factors may have affected outcomes, such as patients’ characteristics, living habits, disease features, and individual laboratory measurements. Thus, these factors did not affect the findings that CP use achieved a significantly shorter LOHS, lower costs, and reduced complications after adjustments.

Large-scale populations with gallstones and data process and application platform utilization are the main strengths in the present study. Furthermore, the findings were demonstrated by adjusting the potential confounders. However, this study was limited by its single-center retrospective design, indicating that further multiple-center trials with larger variable are in need to confirm the results.

In conclusion, findings of our study have demonstrated that patients with CBD stones who accepted the CP appear to be significantly lower in the LOHS, the costs, the rate of antibiotic use, and the incidence of complications. Our study provides further evidence of CP use in Chinese patients and also standardizes gallstone management and treatment.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is widely recognized as a standard endoscopic technique for patients with common bile duct (CBD) stones. However, ERCP is associated with significant morbidity, mortality, and longer preoperative stay. A clinical pathway (CP) is an advanced methodology that provides a sequence of diagnosis, treatment, and management. Although CP implementation could optimize medical treatment and improve efficiency of medical sources utilization, CP implementation for CBD stones has not been fully promoted at present.

Current situation and value of the CP in management of CBD stones receiving ERCP still need to be explored. With the arrival of the era of big-data, we utilized a big-data process and application platform to provide a solid data base and scientific evidence for the establishment of the CP.

The objective of this study was to compare length of hospital stay (LOHS), costs, clinical outcomes, antibiotic use, and postoperative complication rate before and after implementing a CP for patients with CBD stones undergoing ERCP.

Patients with CBD stones from Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital between January 2007 and December 2017 were identified from a big-data, intelligence database platform (Yidu Cloud Technology Ltd., Beijing, China). The enrolled population consisted of two groups which accepted conventional care (non-pathway group, n = 467) and the CP (CP group, n = 2196), respectively. Univariate and multivariable regression/linear models were utilized to compare the medical records and outcomes.

The percentage of antibiotic use and complications in the CP group were significantly less than those in the non-pathway group [adjusted odds ratio (OR) = 0.72, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.55-0.93, P = 0.012, adjusted OR = 0.44, 95%CI 0.33-0.59, P < 0.001, respectively]. Patients experienced lower costs in hospitalization, operation, nursing, medication, and materials (P < 0.001 for all), and even shorter LOHS (P < 0.001) after implementation of the CP. No significant differences in clinical outcomes, readmission rate, or secondary surgery rate were presented between the patients in non-pathway and CP groups.

In conclusion, implementation of the CP for patients with CBD stones undergoing ERCP significantly reduced LOHS, the costs, the rate of antibiotic use, and the incidence of complications without increasing readmission rates. A CP is confirmed to be an effective mode which is explicit about the sequencing, timing, and provision of interventions in the field of CBD stones. Meanwhile, our study provides further big-data evidence of a multidisciplinary CP in Chinese patients.

Despite that this is the rare big-data evidence of a CP in Chinese patients with CBD stones, further multiple-center studies with larger variable are essential to strengthen the results.

We sincerely appreciate Yidu Cloud (Beijing) Technology Co. Ltd., China for providing technical support in extracting data by using the big-data intelligence platform.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Gonzalez-Ojeda AG, Hauser G, Senturk H S- Editor: Yan JP L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Yin SY

| 1. | Acalovschi M. Gallstones in patients with liver cirrhosis: Incidence, etiology, clinical and therapeutical aspects. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:7277-7285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Zhu Q, Sun X, Ji X, Zhu L, Xu J, Wang C, Zhang C, Xue F, Liu Y. The association between gallstones and metabolic syndrome in urban Han Chinese: A longitudinal cohort study. Sci Rep. 2016;6:29937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Anand G, Patel YA, Yeh HC, Khashab MA, Lennon AM, Shin EJ, Canto MI, Okolo PI, Kalloo AN, Singh VK. Factors and Outcomes Associated with MRCP Use prior to ERCP in Patients at High Risk for Choledocholithiasis. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;2016:5132052. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tazuma S. Gallstone disease: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and classification of biliary stones (common bile duct and intrahepatic). Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20:1075-1083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 262] [Cited by in RCA: 311] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Aslan F, Arabul M, Celik M, Alper E, Unsal B. The effect of biliary stenting on difficult common bile duct stones. Prz Gastroenterol. 2014;9:109-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kenny R, Richardson J, McGlone ER, Reddy M, Khan OA. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration versus pre or post-operative ERCP for common bile duct stones in patients undergoing cholecystectomy: Is there any difference? Int J Surg. 2014;12:989-993. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bray MS, Borgert AJ, Folkers ME, Kothari SN. Outcome and management of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography perforations: A community perspective. Am J Surg. 2017;214:69-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Morris S, Gurusamy KS, Sheringham J, Davidson BR. Cost-effectiveness analysis of endoscopic ultrasound versus magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography in patients with suspected common bile duct stones. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0121699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sheffield KM, Ramos KE, Djukom CD, Jimenez CJ, Mileski WJ, Kimbrough TD, Townsend CM, Riall TS. Implementation of a critical pathway for complicated gallstone disease: Translation of population-based data into clinical practice. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:835-843. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Elliott MJ, Gil S, Hemmelgarn BR, Manns BJ, Tonelli M, Jun M, Donald M. A scoping review of adult chronic kidney disease clinical pathways for primary care. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32:838-846. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | De Luca A, Toni D, Lauria L, Sacchetti ML, Giorgi Rossi P, Ferri M, Puca E, Prencipe M, Guasticchi G; IMPLementazione Percorso Clinico Assistenziale ICtus Acuto (IMPLICA) Study Group. An emergency clinical pathway for stroke patients--results of a cluster randomised trial (isrctn41456865). BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Schuur JD, Baugh CW, Hess EP, Hilton JA, Pines JM, Asplin BR. Critical pathways for post-emergency outpatient diagnosis and treatment: Tools to improve the value of emergency care. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18:e52-e63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bradywood A, Farrokhi F, Williams B, Kowalczyk M, Blackmore CC. Reduction of Inpatient Hospital Length of Stay in Lumbar Fusion Patients With Implementation of an Evidence-Based Clinical Care Pathway. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2017;42:169-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | El Baz N, Middel B, van Dijk JP, Oosterhof A, Boonstra PW, Reijneveld SA. Are the outcomes of clinical pathways evidence-based? A critical appraisal of clinical pathway evaluation research. J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;13:920-929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | van Dam PA, Verheyden G, Sugihara A, Trinh XB, Van Der Mussele H, Wuyts H, Verkinderen L, Hauspy J, Vermeulen P, Dirix L. A dynamic clinical pathway for the treatment of patients with early breast cancer is a tool for better cancer care: Implementation and prospective analysis between 2002-2010. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | de Vries M, van Weert JC, Jansen J, Lemmens VE, Maas HA. Step by step development of clinical care pathways for older cancer patients: Necessary or desirable? Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:2170-2178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Shin KC, Lee HS, Park JM, Joo HC, Ko YG, Park I, Kim MJ. Outcomes before and after the Implementation of a Critical Pathway for Patients with Acute Aortic Disease. Yonsei Med J. 2016;57:626-634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Thursky K, Lingaratnam S, Jayarajan J, Haeusler GM, Teh B, Tew M, Venn G, Hiong A, Brown C, Leung V, Worth LJ, Dalziel K, Slavin MA. Implementation of a whole of hospital sepsis clinical pathway in a cancer hospital: Impact on sepsis management, outcomes and costs. BMJ Open Qual. 2018;7:e000355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | van der Kolk M, van den Boogaard M, Ter Brugge-Speelman C, Hol J, Noyez L, van Laarhoven K, van der Hoeven H, Pickkers P. Development and implementation of a clinical pathway for cardiac surgery in the intensive care unit: Effects on protocol adherence. J Eval Clin Pract. 2017;23:1289-1298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Dong W, Huang Z. A Method to Evaluate Critical Factors for Successful Implementation of Clinical Pathways. Appl Clin Inform. 2015;6:650-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Dasari BV, Tan CJ, Gurusamy KS, Martin DJ, Kirk G, McKie L, Diamond T, Taylor MA. Surgical versus endoscopic treatment of bile duct stones. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;CD003327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Platt TE, Smith K, Sinha S, Nixon M, Srinivas G, Johnson N, Andrews S. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration; a preferential pathway for elderly patients. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2018;30:13-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lion KC, Wright DR, Spencer S, Zhou C, Del Beccaro M, Mangione-Smith R. Standardized Clinical Pathways for Hospitalized Children and Outcomes. Pediatrics. 2016;137:pii: e20151202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Singh SB, Shelton AU, Greenberg B, Starner TD. Implementation of cystic fibrosis clinical pathways improved physician adherence to care guidelines. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2017;52:175-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Vujasinovic M, Makuc J, Tepes B, Marolt A, Kikec Z, Robac N. Impact of a clinical pathway on treatment outcome in patients with acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:9150-9155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Nishimura K, Yasui M, Nishimura T, Oga T. Clinical pathway for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Method development and five years of experience. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2011;6:365-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Donà D, Zingarella S, Gastaldi A, Lundin R, Perilongo G, Frigo AC, Hamdy RF, Zaoutis T, Da Dalt L, Giaquinto C. Effects of clinical pathway implementation on antibiotic prescriptions for pediatric community-acquired pneumonia. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0193581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Kim HE, Kim YH, Song KB, Chung YS, Hwang S, Lee YJ, Park KM, Kim SC. Impact of critical pathway implementation on hospital stay and costs in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. Korean J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2014;18:14-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Husni ME, Losina E, Fossel AH, Solomon DH, Mahomed NN, Katz JN. Decreasing medical complications for total knee arthroplasty: Effect of critical pathways on outcomes. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Burgers PT, Van Lieshout EM, Verhelst J, Dawson I, de Rijcke PA. Implementing a clinical pathway for hip fractures; effects on hospital length of stay and complication rates in five hundred and twenty six patients. Int Orthop. 2014;38:1045-1050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Walters DM, McGarey P, LaPar DJ, Strong A, Good E, Adams RB, Bauer TW. A 6-day clinical pathway after a pancreaticoduodenectomy is feasible, safe and efficient. HPB (Oxford). 2013;15:668-673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |