Published online Dec 28, 2019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i48.6949

Peer-review started: October 8, 2019

First decision: November 27, 2019

Revised: December 6, 2019

Accepted: December 21, 2019

Article in press: December 22, 2019

Published online: December 28, 2019

Processing time: 81 Days and 2.7 Hours

Pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy (PTTM) is a rare condition in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC); to date, few cases have been reported. While hepatic dysfunction has been focused on the later stages of HCC, the management of symptoms in PTTM is important for supportive care of the cases. For the better understanding of PTTM in HCC, the information of our recent case and reported cases have been summarized.

A patient with HCC exhibited acute and severe respiratory failure. Radiography and computed tomography of the chest revealed the multiple metastatic tumors and a frosted glass–like shadow with no evidence of infectious pneumonia. We diagnosed his condition as acute respiratory distress syndrome caused by the lung metastases and involvement of the pulmonary vessels by tumor thrombus. Administration of prednisolone to alleviate the diffuse alveolar damages including edematous changes of alveolar wall caused by the tumor cell infiltration and ischemia showed mild improvement in his symptoms and imaging findings. An autopsy showed the typical pattern of PTTM in the lung with multiple metastases.

PTTM is caused by tumor thrombi in the arteries and thickening of the pulmonary arterial endothelium leading to the symptoms of dyspnea in terminal staged patients. Therefore, supportive management of symptoms is necessary in the cases with PTTM and hence we believe that the information presented here is of great significance for the diagnosis and management of symptoms of PTTM with HCC.

Core tip: Pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy is caused by tumor thrombi in the arteries and thickening of the pulmonary arterial endothelium leading to the symptoms of dyspnea in terminal staged patients. Therefore, supportive management of symptoms is necessary in the cases with pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy, however, as the hepatic failure, bleeding, and encephalopathy have been focused in these cases with hepatocellular carcinoma and it is rare condition in the cases with hepatocellular carcinoma, only few cases have been reported. Therefore, we have reported the minute clinical and pathological information of our recent case and reviewed literatures of reported cases to date in this paper.

- Citation: Morita S, Kamimura K, Abe H, Watanabe-Mori Y, Oda C, Kobayashi T, Arao Y, Tani Y, Ohashi R, Ajioka Y, Terai S. Pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy of hepatocellular carcinoma: A case report and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol 2019; 25(48): 6949-6958

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v25/i48/6949.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i48.6949

Various pathologic conditions, including diffuse alveolar lesions, lymphangiopathy, and pulmonary microembolism, are known causes of respiratory failure in cases of pulmonary malignancy[1]; however, these conditions are relatively rare in cases of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), possibly because HCC causes hepatic dysfunction and/or bleedings rather than respiratory dysfunction in the terminal stage. Therefore, pulmonary tumor microembolisms, including those of pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy (PTTM), are especially rare in HCC cases; and only a few cases have been reported, and the symptoms, imaging findings, therapeutic options, and prognoses have not been summarized to date. PTTM, first reported by von Herbay et al[2] in 1990, is a special cause of pulmonary tumor embolism in which tumor cells cause thickening of pulmonary arterial endothelium or form thrombi, which in turn cause narrowing and occlusion of the pulmonary arteries, resulting in pulmonary hypertension, dyspnea, and hypoxemia[3]. Our recent case with HCC who developed PTTM exhibited dyspnea with severe respiratory failure was diagnosed by minute histological analysis on autopsy and the information obtained was important to manage the symptoms in that stage. For a better understanding of the disease and management of symptoms, we have conducted a literature review of 18 reported cases[1,4-20] with our case.

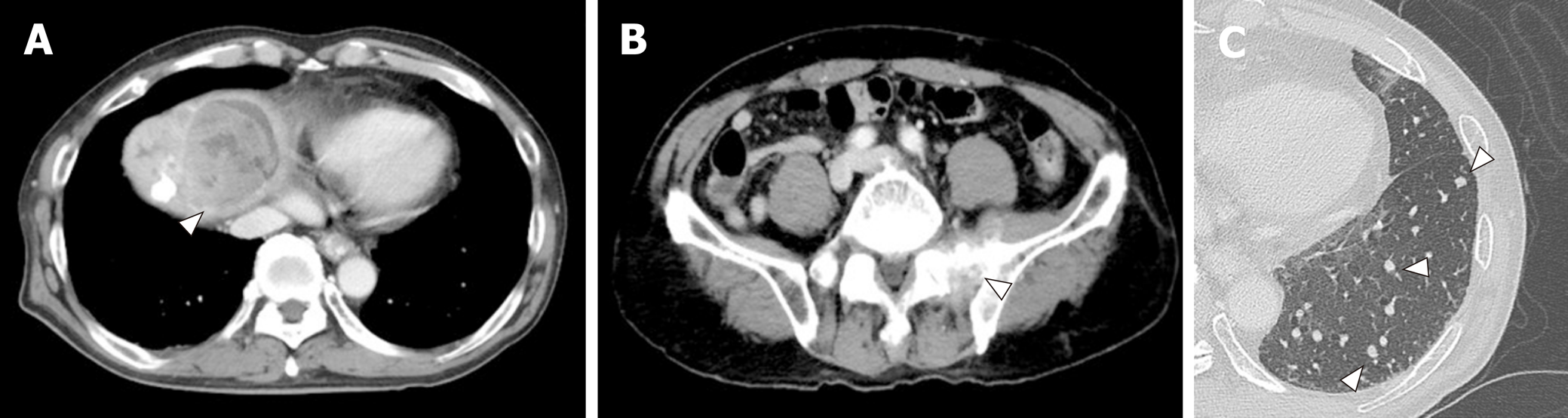

A 72-year-old Japanese man was diagnosed with HCC and liver cirrhosis, caused by alcohol abuse, in 2011, and was referred to our hospital for therapeutic management. Since then, transcatheter arterial chemoembolization and radiofrequency ablation had been performed repeatedly, followed by the oral administration of sorafenib, 400 mg daily. After 1 year of sorafenib treatment, he was admitted to our hospital for dyspnea and low back pain. Computed tomographic (CT) scans revealed multiple HCC tumors in the liver (Figure 1A), as well as sacral bone metastases (Figure 1B) and multiple metastatic nodules in the lungs (Figure 1C) but no ascites.

The laboratory examination showed a mild increase in aspartate aminotransferase (74 IU/L), blood urea nitrogen (31 IU/L), creatinine (1.0 mg/dL), and C-reactive protein (5.36 mg/dL); mild decrease of prothrombin time (76% of normal), and serum albumin (3.4 g/dL). The Levels of tumor markers—alpha-fetoprotein, Lens culinaris agglutinin–reactive alpha-fetoprotein isoform, and des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin—were significantly increased, to 67,183 ng/mL, 37.2%, and 75,000 milli-arbitrary units per milliliter or higher, respectively (Table 1). No increase in white blood cell count, and other hepatobiliary enzymes were marked.

| Hematology | Biochemistry | Marker | |||

| WBC | 4840/μL | TP | 8.0 g/dL | HBs Ag | - |

| Neutro | 70.5 % | Alb | 3.4 g/dL | Anti-HBs | - |

| Lymp | 16.9 % | BUN | 14 mg/dL | Anti-HBc | - |

| Eos. | 3.7 % | Cre | 0.59 mg/dL | Anti-HCV | - |

| Bas. | 0.4 % | T-Bil | 1.0 mg/dL | ||

| Mon. | 8.5 % | D-Bil | 0.2 mg/dL | AFP | 67183 ng/mL |

| RBC | 392 × 104 /μL | AST | 74 IU/L | AFP-L3 | 37.2 % |

| Hb | 12.4 g/dL | ALT | 31 IU/L | PIVKA-II | > 75000 mAU/mL |

| Ht. | 35.9 % | ALP | 828 IU/L | KL-6 | 300 IU/mL |

| Plt. | 8.0 × 104 /μL | LDH | 432 IU/L | SP-D | 87.6 ng/mL |

| γ-GTP | 737 IU/L | ||||

| ChE | 165 IU/L | ||||

| NH3 | 92 μL/dL | ||||

| Na | 130 mEq/L | Blood Gas Analysis of 6th day (O2 2L) | |||

| K | 3.8 mEq/L | SpO2 | 91% | ||

| Cl | 100 mEq/L | pH | 7.456 | ||

| Coagulation | P | 3.3 mg/dL | pCO2 | 35.2 mmHg | |

| PT% | 76 % | Ca | 9.0 mg/dL | pO2 | 62.9 mmHg |

| PT-INR | 1.15 | CRP | 5.37 mg/dL | HCO3 | 24.3 mmol/L |

| APTT | 36.3 sec | FBS | 103 mg/dL | BE | 0.7 mmol/L |

| HbA1c | 5.5 % | ||||

| TG | 58 mg/dL | ||||

| HDL-C | 50 mg/dL | ||||

| LDL-C | 138 mg/dL | ||||

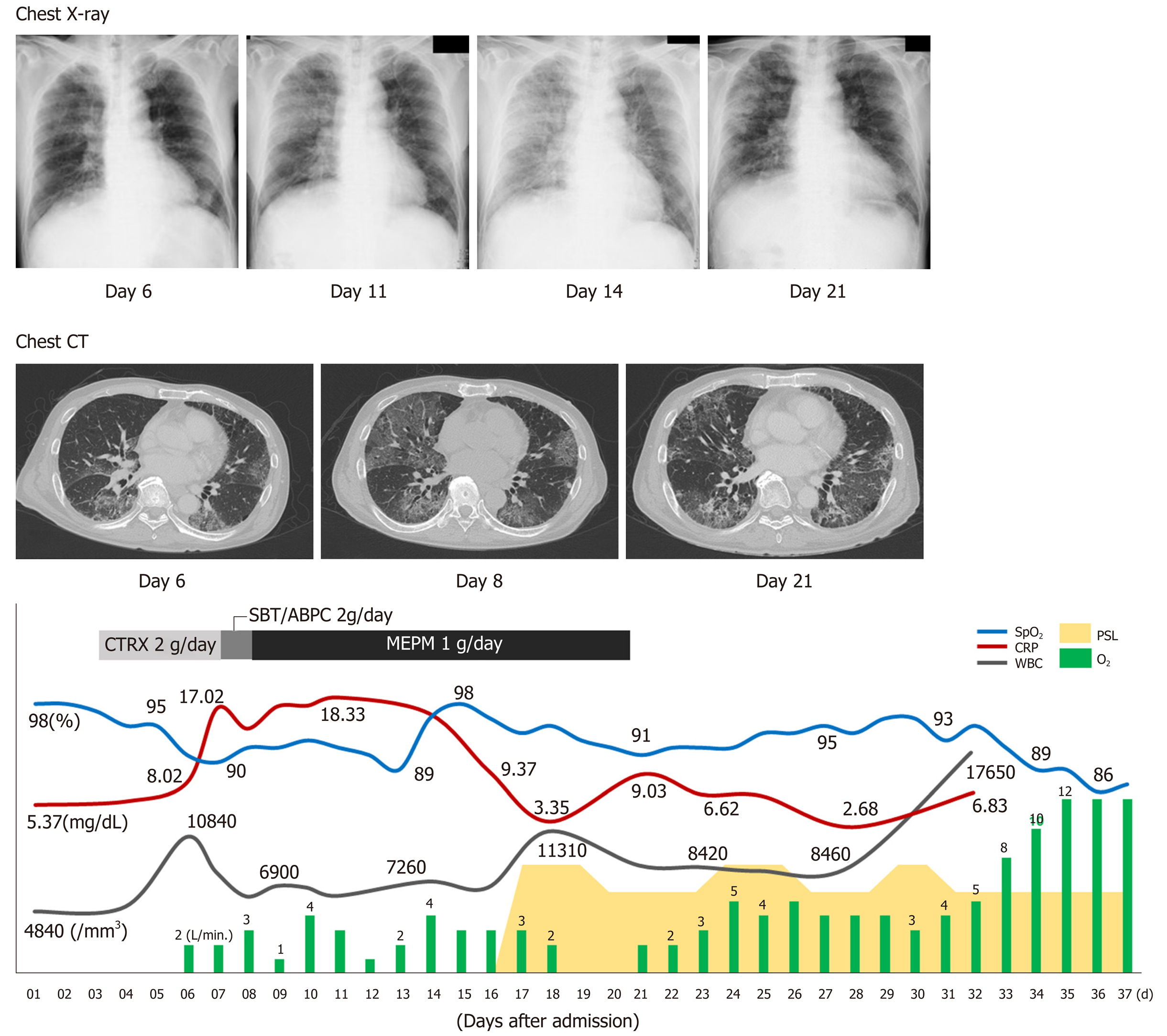

On the sixth day after hospital admission, the patient’s respiratory condition worsened, and his blood gas analysis showed oxygen saturation (SpO2) of 91%, pH of 7.456, carbon dioxide tension of 35.2 mmHg, oxygen tension of 62.9 mmHg, bicarbonate level of 24.3 mmol/L, and BE of 0.7 mmol/L, with supplementation of 2 L/min of oxygen (Table 1, Figure 2). The chest radiograph showed a frosted glass-like shadow in the upper right lobe, middle lobe, and the lower left lobe (Figure 2). The blood and sputum cultures revealed no evidence of infectious pneumonia; however, respiratory distress and decreasing arterial blood oxygen saturation continued, and chest CT examination revealed worsening of the frosted glass-like shadow on day 8 (Figure 2). On the basis of these findings, and because antibiotics produced no response, we diagnosed his condition as acute respiratory distress syndrome, potentially a result of the lung metastasis and involvement of the pulmonary vessels by tumor thrombus.

Chest radiographs showed worsening on day 14 (Figure 2). To alleviate the respiratory failure caused by the infiltration of the inflammatory cells and the reaction in the lung, we started oral administration of prednisolone, 80 mg daily, on day 16 after admission (Figure 2). The frosted glass-like shadow on chest radiographs and CT studies (Figure 2) showed temporary improvement and the symptom of dyspnea showed mild improvement; however, the patient’s respiratory condition and the data from the blood gas analysis did not improve with oxygen supplementation. The patient’s general condition worsened gradually and he died on the 37th day of hospitalization (Figure 2).

With the informed consent of the patient’s family, autopsy was performed to assess the cause of the respiratory failure and the frosted glass-like shadow. Macroscopically, the lung appeared to be hard and yellowish, and the presence of multiple tumors in the area was confirmed (Figure 3A). Microscopically, these tumors were confirmed to be metastases of HCC (Figure 3B), and multiple pulmonary artery tumor emboli with diffuse alveolar damages of detachment of alveolar epithelial cells, edematous changes of alveolar wall, accumulation of macrophages, and exudation of fibrinous tissue were seen (Figure 3C) and in part with recanalization in the tumor thrombus and the fibrocellular intimal proliferation (Figure 3D). In addition, medial thickening of the arterioles (Figure 3E) were seen and the tumor emboli (Figure 3F) were accompanied by CD31-positive endothelial cell growth (Figure 3G) with fibrocellular intimal proliferation (Figure 3H) which are the characteristics of PTTM.

On the basis of these findings, the diagnosis was PTTM and diffuse pulmonary alveolar damage due to tumor emboli, which led to the cause of respiratory failure.

To alleviate the respiratory failure caused by the infiltration of the inflammatory cells and the reaction in the lung, we started oral administration of prednisolone, 80 mg daily, on day 16 after admission.

The patient’s general condition worsened gradually and he died on the 37th day of hospitalization.

In the cases of pulmonary microembolism caused by tumor cells, the tumor cells move intravenously or lymphatically to pulmonary arteries that are smaller than muscular arteries, and cause embolism, which may in turn cause pulmonary hypertension or respiratory failure[1]. PTTM is a special cause of pulmonary tumor embolism, in which tumor cells cause thickening of the pulmonary arterial endothelium or form thrombi, that cause narrowing and occlusion of the pulmonary arteries[2].

In a report by Yamashita et al[3] who surveyed findings from autopsies of 2215 cases of malignant tumors, 30 cases (1.4%) were diagnosed with PTTM, and 21 of those cases exhibited hypercoagulability. Eighteen cases (60%) were with gastric cancers; the others include the carcinomas of the breast, pulmonary system, prostate, ovary, and pancreas. The most common histological type was glandular carcinoma, which was observed in 28 cases (93%). With regard to HCC as the primary lesion in cases of PTTM, only a few reports have been published to date, and the symptoms, imaging findings, therapeutic options, and prognoses have not been summarized; we performed a literature review of 18 reported cases and summarized the information with that of our case[1,4-20] (Table 2). According to our summary, the overall male-female ratio for all PTTM cases was 2:1, and of the 17 patients with PTTM that started as HCC, 15 (89%) were male (Table 2).

| Case | Ref. | Age (yr) | Gender | Etiology | Child-Pugh score | BCLC stage | Symptom | Respiratory failure | SIRS score | Invasion to IVC | Diagnosis | Treatment | Steroid | Outcome | Prognosis (d) | Image of lung | Pathology of lung | Pathology of liver |

| 1 | Uruga et al[1] | 60 | F | HCV | B | C | Dyspnea | + | 2 | N/A | Autopsy | Oxygen | + | Death | 4 | Mild elevation of CT number | Moderately differentiated HCC in lung small blood vessels | N/A |

| 2 | Nakamura et al[4] | 52 | M | Alcohol | B | C | Fever, dry cough | + | 3 | + | Lung scintigraphy | Decompression | + | Death | 330 | Multiple plaques on both lungs | Multiple tumor embolism of both pulmonary arteries | Undifferentiated HCC |

| 3 | Sato et al[5] | 58 | M | N/A | B | C | Dyspnea | + | 3 | N/A | Autopsy | Oxygen | - | Death | 15 | No imaging | Multiple pulmonary arterial tumor, thrombus | N/A |

| 4 | Shinzato et al[6] | 56 | M | N/A | N/A | C | Dyspnea, consciousness disorder | + | 2 | + | Autopsy | N/A | - | Death | 2 | Blurred nodular shadow, airbronchogram | Tumor embolism, hemorrhagic necrosis | differentiated HCC |

| 5 | Ohta et al[7] | 62 | M | Alcohol + HCV | B | C | Chest pain | + | N/A | + | Autopsy | N/A | - | Death | 60 | Enhancement of pulmonary artery | Multiple pulmonary artery tumor embolism | Medium to well-differentiated HCC |

| 6 | Koskinas et al[8] | 30 | F | HBV | N/A | C | Shortness of breath | + | 3 | N/A | Autopsy | Oxygen | - | Death | 0 | No imaging | Invasion of vein by the carcinoma | N/A |

| 7 | Jäkel et al[9] | 48 | M | Alcohol | N/A | C | Ascites | N/A | N/A | + | Autopsy | N/A | - | Death | 16 | Unremarkable | Multiple pulmonary artery tumor embolism | N/A |

| 8 | Yamauchi et al[10] | 58 | M | HBV | N/A | C | Dyspnea | + | 0 | + | Autopsy | Oxygen | - | Death | 5 | Coin lesion | Tumor thrombi in both pulmonary arteries | sarcomatoid HCC |

| 9 | Tanaka et al[11] | 76 | M | HCV | B | C | Dyspnea | + | N/A | N/A | Autopsy | Antibiotic, FOY | - | Death | 13 | Many ground-glass patterns and partly consolidation in both lung field multiple defect (lung scintigraphy) | Venous thrombi of the poorly differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma | poorly HCC |

| 10 | Nepal et al[12] | 59 | M | Alcohol + HCV | B | C | Abdominal fullness | 0 | 1 | + | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Unremarkable | N/A | N/A |

| 11 | Chan et al[13] | 52 | M | HBV | N/A | C | Malaise, loss of appetite | 0 | N/A | + | Autopsy | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | No imaging | Massive necrotic tumor emboli in both pulmonary trunks. | Moderately differentiated |

| 12 | Diaz Castro et al[14] | 71 | M | HCV | N/A | C | Chest pain | + | N/A | + | Autopsy | Urokinase | - | Death | 4 d | No imaging | Tumor thrombi in pulmonary arteries | N/A |

| 13 | Gutiérrez-Macías et al[15] | 41 | M | Alcohol | N/A | C | Dyspnea, chest pain, sweating | + | 3 | N/A | Autopsy | Antibiotic, antithrombotic therapy | + | Death | 2 | Filling defect in the left pulmonary artery | Small blood vessels occluded by clusters of malignant cells | N/A |

| 14 | Wilson et al[16] | 65 | M | N/A | N/A | C | Dyspnea | + | N/A | + | Embolic material | Antithrombotic therapy, embolic material recovery | - | Survive | N/A | No imaging | N/A | N/A |

| 15 | Mularek-Kubzdela et al[17] | 49 | M | HBV | N/A | C | Shortness of breath, lower extremity edema | + | N/A | + | CT,lung scintigraphy, United States | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | No imaging | N/A | N/A |

| 16 | Lin et al[18] | 57 | M | HBV | B | C | Chest pain、dyspnea | + | N/A | + | Autopsy, echocardiography | Surgery | - | Death | 40 | Multiple segmental perfusion defects (lung scintigraphy) | N/A | N/A |

| 17 | Papp et al[19] | 63 | M | HBV or HCV | N/A | C | Fever | - | N/A | + | Autopsy, echocardiography | Surgery | - | Death | N/A | No imaging | Tumor embolism, right atrium tumor embolism | small round cell HCC |

| 18 | Clark et al[20] | 65 | M | HCV | N/A | C | Dyspnea, abdominal pain, malaise | + | N/A | + | Autopsy | Comfort care | - | Death | 4 | No imaging | The large right atrial tumor thrombus and multiple pulmonary emboli | N/A |

| Our case | N/A | 72 | M | Alcohol | A | C | Dyspnea | + | 2 | N/A | Autopsy | Oxygen | + | Death | 37 | Glass shadow of bilateral lungs | Micropulmonary artery tumor embolism in both lung | Moderate to poorly differentiated HCC |

For the symptoms, respiratory discomfort is the chief symptom recognized with PTTM. Of the 17 patients with HCC, 9 (53%) displayed symptoms of respiratory discomfort; in addition, 4 had chest pain, 2 had pyrexia, 2 had shortness of breath, and 1 each had cough, disturbance of consciousness, and ascites. Respiratory discomfort rapidly progresses to pulmonary hypertension and right-sided heart failure, and most cases result in death a short time after the appearance of respiratory discomfort. Respiratory discomfort ultimately occurred in 13 of the 17 cases (Table 2), and of those cases, 6 (46%) presented with more than two criteria for systemic inflammatory response syndrome.

For the imaging findings of PTTM, pulmonary CT scans show consolidation which means an increase in absorption by the pulmonary parenchyma that obscures the background of blood vessels and the bronchial wall and the appearance of ground-glass attenuation, small nodules, and a tree-in-bud pattern. In our particular case, multiple small nodules appeared in the left inferior lobe; a decrease in SpO2 coincided with the increase in systemic inflammatory response syndrome score; and a chest radiograph showed ground-glass opacity over the area from the right superior lobe to the inferior lobe and over to the left inferior lobe. A chest CT scan taken at the same time showed ground-glass attenuation over both lungs. The summary of the reported cases showed various imaging including tumor nodular shadows, air bronchograms, enlargement of both the heart shadow and pulmonary arterial shadows, and ground-glass attenuation, therefore, there were no specific imaging findings directly suggesting the tumor embolism or pulmonary embolism. Because there is no typical pattern in imaging findings, it is difficult to diagnose PTTM while an affected patient is alive. As part of diagnosis, lung perfusion scintigraphy or cardiac ultrasonography is used to detect pulmonary hypertension[4]. In one report, cytodiagnosis was made with a specimen of pulmonary arterial blood taken with a Swan-Ganz’s catheter[21]; however, this method requires caution because the procedure is highly invasive and risky in patients with respiratory distress. In that report, the patient received a definitive diagnosis but died 4 d later. Among the cases in the literature, definitive diagnosis was obtained through autopsy in 13 cases, lung perfusion scintigraphy in 2 cases, cardiac ultrasonography in 2 cases and recovery of embolus in 1 case. The pathological findings have not been described minutely, and our patient showed not only the tumor embolisms, the thickening of vascular endothelium and fiber were confirmed which are suggesting the histological features of PTTM.

For therapeutic options, as far as we could confirm, all patients with respiratory distress were administered oxygen, and additional treatments included antibiotics in two cases, one case of gabexate mesilate infusion in one case, and antithrombotic urokinase therapy in two cases. No effective therapeutic options have been established for PTTM at this stage. We used prednisolone infusion with the purpose of alleviating respiratory distress and improving the patient’s deteriorating systemic condition, and the mild improvement of the symptom with the reduction of the ground-grass opacity in chest radiographs and CT scans were seen, however, no data of the respiratory distress and the necessary oxygen volume did not decrease. Based on the literature review, steroids were administered to three patients, and one of them showed the improvement of the images (Table 2). The prognosis for patients with PTTM is extremely poor; most of such patients die within 1 week of developing respiratory distress[22]. Among the cases featured in our literature review, only one patient survived. The shortest period between the commencement of treatment for respiratory distress and death was 0, the longest was 330 d, the average was 41 d, and the median was 9 d. PTTM is difficult to diagnose with general imaging tools, and a poor prognostic conditions with malignant tumors, therefore, the supportive care to reduce the symptoms by prednisolone, opioid, and etc. should be considered for the better terminal care.

Our summary demonstrated the poor prognosis of the PTTM of HCC and supportive care using oxygen, prednisolone, opioid, etc. might be effective to reduce the symptoms. Further accumulation of information from cases will be of great help for physicians diagnose, manage, and care the patients and their symptoms.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: El-Hawary AK, Tchilikidi KY, Wang SK S-Editor: Wang J L-Editor: A E-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Uruga H, Fujii T, Kurosaki A, Hanada S, Takaya H, Miyamoto A, Morokawa N, Homma S, Kishi K. Pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy: a clinical analysis of 30 autopsy cases. Intern Med. 2013;52:1317-1323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | von Herbay A, Illes A, Waldherr R, Otto HF. Pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy with pulmonary hypertension. Cancer. 1990;66:587-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yamashita N, Tanimoto H, Yamamoto H, Nishiura S, Nomura H. [Hypoxemia due to pulmonary tumor microembolisms from a hepatocellular carcinoma: a case report]. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2015;112:1060-1066. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nakamura Y, Tamura A, Fijimoto H, Nishiura M, Okusa T, Nakamura R, Kuyama Y, Hayashi M, Kayano T. [A case of hepatocellular carcinoma with growth into the right atrium, pulmonary tumor embolism, and cerebral metastasis]. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 1985;82:319-323. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Sato T, OH K, Hirose H, Nagasawa H, Suzuki Y, Yamashita T, Kohno H, Tai H, Horiguchi M. Fatal respiratory failure due to tumor embolism in hepatoma. Tokyo Jikeikai Med J. 1985;100:983-988. |

| 6. | Shinzato J, Yamashita Y, Takahashi M, Miura K. [A case of pulmonary infarction secondary to emboli of hepatoma]. Rinsho Hoshasen. 1990;35:971-974. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Ohta H, Matsumoto A, Mizukami Y, Nakano Y, Ohta T, Arisato S, Murakami M, Orii Y, Sato T. [Report of an autopsy cases of hepatocellular carcinoma with marked pulmonary hypertension due to multiple pulmonary thrombus]. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 1998;95:900-904. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Koskinas J, Betrosian A, Kafiri G, Tsolakidis G, Garaziotou V, Hadziyannis S. Combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma presented with massive pulmonary embolism. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:1125-1128. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Jäkel J, Ramaswamy A, Köhler U, Barth PJ. Massive pulmonary tumor microembolism from a hepatocellular carcinoma. Pathol Res Pract. 2006;202:395-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yamauchi Y, Kuroshima N, Sugimoto T, Naruke Y, Mihara Y, Ito M, Matsuoka Y, Nishikawa A, Murata T, Abiru S, Komori A, Yatsuhashi H, Ishibashi H. A case of sudden death due to pulmonary arterial tumor-embolism associated with sarcomatoid hepatocellular carcinoma. Med J Nat Nagasaki Medical Center. 2011;13:72-75. |

| 11. | Tanaka K, Nakasya A, Miyazaki M, Takao S, Higuchi N, Tanaka M, Tanaka Y, Kato M, Kato K, Takayanagi R, Aishima S. A case of hepatocellular carcinoma with respiratory failure caused by widespread tumor microemboli. Fukuoka Igaku Zasshi. 2011;102:298-302. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Nepal M, Bhattarai A, Adenawala H, Usman H. Cardiac extension of Hepatocellular carcinoma with pulmonary tumormicroembolism. Int J Gastroenterol. 2008;7. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chan GS, Ng WK, Ng IO, Dickens P. Sudden death from massive pulmonary tumor embolism due to hepatocellular carcinoma. Forensic Sci Int. 2000;108:215-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Diaz Castro O, Bueno H, Nebreda LA. Acute myocardial infarction caused by paradoxical tumorous embolism as a manifestation of hepatocarcinoma. Heart. 2004;90:e29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gutiérrez-Macías A, Barandiarán KE, Ercoreca FJ, De Zárate MM. Acute cor pulmonale due to microscopic tumour embolism as the first manifestation of hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:775-777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wilson K, Guardino J, Shapira O. Pulmonary tumor embolism as a presenting feature of cavoatrial hepatocellular carcinoma. Chest. 2001;119:657-658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mularek-Kubzdela T, Stachowiak W, Grajek S, Skorupski W, Juszkat R, Půzak D, Cieśliński A, Ziemiański A. [A case of primary hepatocellular carcinoma with tumor thrombus in the right atrium and massive pulmonary embolism]. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 1996;95:245-249. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Lin HH, Hsieh CB, Chu HC, Chang WK, Chao YC, Hsieh TY. Acute pulmonary embolism as the first manifestation of hepatocellular carcinoma complicated with tumor thrombi in the inferior vena cava: surgery or not? Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:1554-1557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Papp E, Keszthelyi Z, Kalmar NK, Papp L, Weninger C, Tornoczky T, Kalman E, Toth K, Habon T. Pulmonary embolization as primary manifestation of hepatocellular carcinoma with intracardiac penetration: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:2357-2359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Clark T, Maximin S, Shriki J, Bhargava P. Tumoral pulmonary emboli from angioinvasive hepatocellular carcinoma. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2014;43:227-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ito M, Abe Y, Kita A, Yunoki K, Tanaka C, Mizutani K, Ito K, Nakagawa E, Komatsu R, Haze K, Naruko T, Itoh A. A case of pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy diagnosed by cytological examination of aspirated pulmonary artery blood. Shinzo. 2013;45:1254-1259. |

| 22. | Hayashi K, Shinohara S, Suehiro A, Kishimoto I, Harada H, Sato Y, Uehara K. A fatal case with pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy (PTTM) originating from adenoid cystic carcinoma in sublingual gland. J Jap Soc Head Neck Surgery. 2017;27:117-121. |