Published online Dec 21, 2019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i47.6857

Peer-review started: June 17, 2019

First decision: August 3, 2019

Revised: November 20, 2019

Accepted: November 23, 2019

Article in press: November 23, 2019

Published online: December 21, 2019

Processing time: 188 Days and 15.1 Hours

The burden of carcinoid syndrome (CS) among patients with neuroendocrine tumors is substantial and has been shown to result in increased healthcare resource use and costs. The incremental burden of CS diarrhea (CSD) is less well understood, particularly among working age adults who make up a large proportion of the population of patients with CS.

To estimate the direct medical costs of CSD to a self-insured employer in the United States.

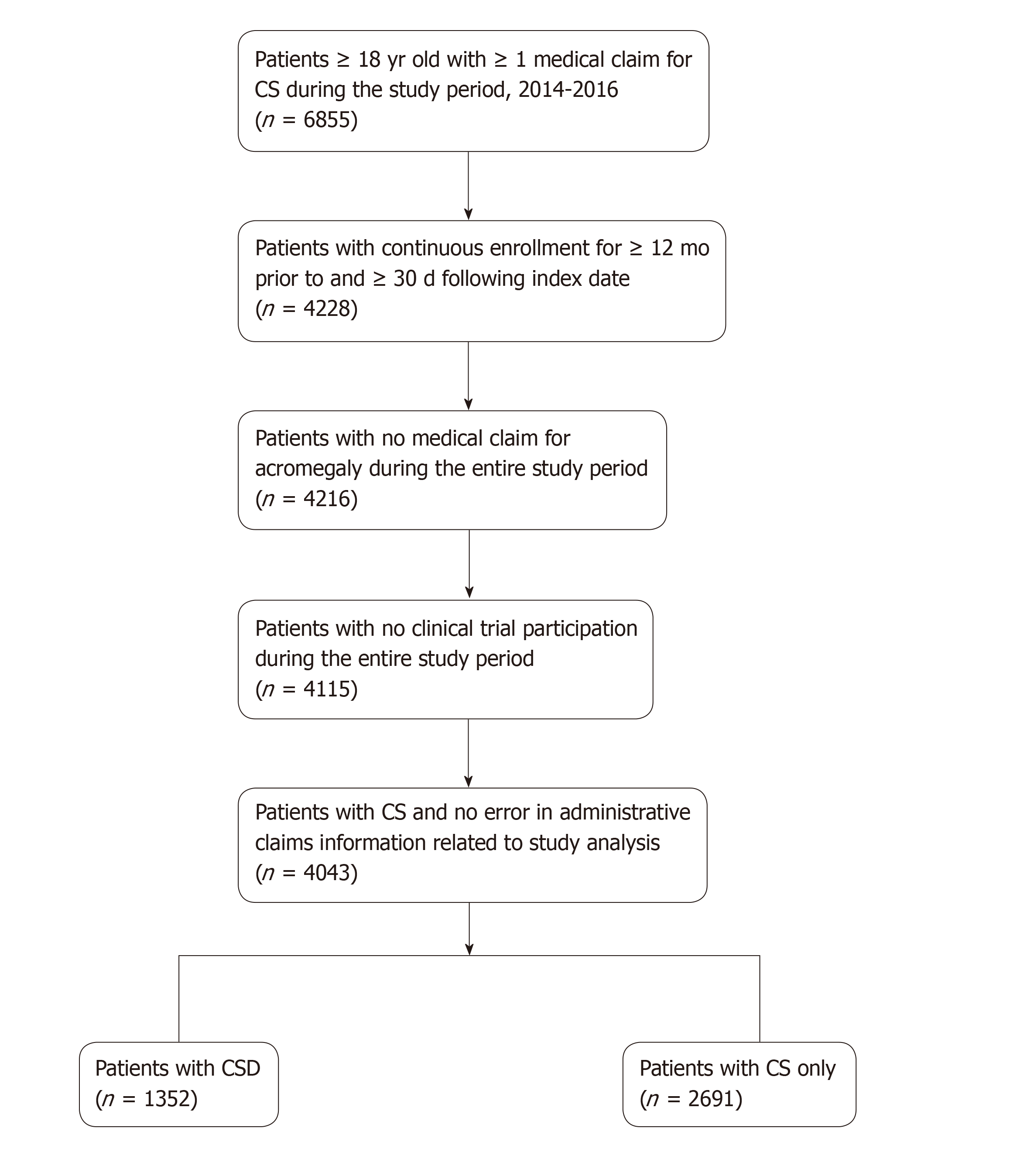

CS patients with and without CSD were identified in the IBM® MarketScan® Database, including the Medicare Supplemental Coordination of Benefits database. Eligible patients had ≥ 1 medical claim for CS with continuous health plan enrollment for ≥ 12 mo prior to their first CS diagnosis and for ≥ 30 d after, no claims for acromegaly, and no clinical trial participation during the study period (2014-2016). Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics, including comorbidities and treatment, were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Measures of healthcare resource use and costs were compared between patients with and without CSD, including Emergency Department (ED) visits, hospital admissions and length of stay, physician office visits, outpatient services, and prescription claims, using univariate and multivariate analyses to evaluate associations of CSD with healthcare resource use and costs, controlling for baseline characteristics.

Overall, 6855 patients with CS were identified of which 4,043 were eligible for the analysis (1352 with CSD, 2691 with CS only). Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were similar between groups with the exception of age, underlying tumor type, and health insurance plan. Patients with CSD were older, had more comorbidities, and received more somatostatin analog therapy at baseline. Patients with CSD required greater use of healthcare resources and incurred higher costs than their peers without CSD, including hospitalizations (44% vs 25%) and ED visits (55% vs 31%). The total adjusted annual healthcare costs per patient were 50% higher (+ $23865) among those with CSD, driven by outpatient services (+ 56%), prescriptions (+ 48%), ED visits (+ 26%), physician office visits (+ 21%), and hospital admissions (+ 11%).

The economic burden of CSD is greater than that of CS alone among insured working age adults in the United States, which may benefit from timely diagnosis and management.

Core tip: Healthcare resource use and costs among patients with carcinoid syndrome (CS) are known to be high, but the incremental burden of CS diarrhea (CSD) is less well understood. We analyzed insured, working age CS patients with and without CSD using the MarketScan® database (2014-2016) and observed a greater economic burden in the presence of CSD. Patients with CSD required more healthcare resources than their peers without CSD, including hospitalizations (44% vs 25%) and Emergency Department visits (55% vs 31%). Total adjusted mean annual costs per patient were 50% higher (+ $25865), driven largely by the use of more outpatient services (+56%).

- Citation: Dasari A, Joish VN, Perez-Olle R, Dharba S, Balaji K, Halperin DM. Direct costs of carcinoid syndrome diarrhea among adults in the United States. World J Gastroenterol 2019; 25(47): 6857-6865

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v25/i47/6857.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i47.6857

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs), formerly known as carcinoid tumors, are potentially functional secretory tumors that arise in neuroendocrine cells throughout the body, most often in the gastrointestinal system but also in the pancreas, lungs, and other organs[1-3]. NETs have an estimated incidence of 70 cases per 1 million people, with an increasing prevalence over the past 20 years due to improvements in identification and characterization[3-5]. NETs produce hormonal factors that induce carcinoid syndrome (CS), characterized primarily by diarrhea, flushing, hypotension, tachycardia, and bronchoconstriction that may include cardiovascular and/or pulmonary complications[6-8]. One-third (35%) of patients with NETs may develop CS, 80% of whom are likely to have associated diarrhea (CSD)[9,10].

Carcinoid syndrome has been shown to affect tumor characteristics and advancement, causing substantial morbidity and reducing patient quality of life and survival[11-14]. Nearly all (97%) CS patients in a recent clinical trial reported bowel movement-related issues at baseline along with flushing (83%), abdominal pain (63%), and low energy (63%), among other symptoms[12]. In addition to substantial clinical morbidity, patients with CSD require greater healthcare resources than their peers without diarrhea[14]. Working age adults with CSD have significantly more hospitalizations, Emergency Department (ED) visits, and CS-related office visits within 1 year of diagnosis compared to peers without diarrhea[15]. Given the rare nature of CS and CSD, the prevalence and burden of CSD among patients with NETs has not been well characterized. This study aimed to further characterize the direct costs of CSD in a population of insured adults in the United States.

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients with CS or CSD from January 12014 through December 312016. Patients with a diagnosis of CS (ICD-9259.2; ICD-10 E34.0) with or without CSD (ICD-9 564.5, 787.91; ICD-10 K59.1, R19.7) were identified in the IBM® MarketScan® Database, including the Medicare Supplemental Coordination of Benefits database. Eligible patients were adults ≥ 18 years of age at the time of first CS medical claim (index) with continuous health plan enrollment 12 mo prior to the index date and ≥ 30 d after; no medical claim for acromegaly; and no clinical trial participation during the study period.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were identified, including health insurance plan type, Charlson Comorbidity Index, comorbidities, and baseline CS or CSD treatment. Overall and CSD-related measures of healthcare resource use and costs included ED visits, hospital admissions and length of stay, physician office visits, outpatient services, and prescription claims.

Descriptive analyses were conducted using measures of central tendency including baseline demographic and clinical characteristics and treatment, and healthcare resource use and costs among patients with and without non-infectious diarrhea (CSD). Univariate analyses of baseline characteristics and outcomes between patients with and without CSD were performed. Student’s t-test was used to analyze continuous variables and Chi-square tests for categorical variables. Multivariate analyses were performed using general linear models with appropriate distribution and link to evaluate associations of CSD with healthcare resource use and costs, controlling for baseline characteristics. All statistical tests were 2-sided unless stated otherwise with significance tests based on alpha ≤ 0.05, and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using 2-sided criteria. All statistical analyses were performed and reviewed by the biostatistician, Samyukta Dharba, and conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States).

Overall, 6855 patients with ≥ 1 medical claim for CS were identified during the study period, 4043 of whom (1352 with CSD, 2691 with CS only) were eligible for the analysis (Figure 1). Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were similar between groups with the exception of age, underlying tumor type, and health insurance plan (Table 1). Patients with CSD were older, had more comorbidities, and received more somatostatin analog therapy (SSA) at baseline.

| CSD (n = 1352) | CS only (n = 2691) | P value | |

| Age (yr) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 60.3 (13.8) | 57.3 (13.9) | < 0.001 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Female | 799 (59) | 1477 (55) | 0.011 |

| Male | 553 (41) | 1214 (45) | |

| Primary tumor site, n (%) | |||

| Malignant carcinoid tumor of unspecified site | 295 (22) | 331 (12) | < 0.0001 |

| Malignant carcinoid tumors of the small intestine | 303 (22) | 328 (12) | < 0.0001 |

| Malignant carcinoid tumors of the appendix, large intestine, rectum | 110 (8) | 137 (5) | < 0.0001 |

| Malignant carcinoid tumors of other sites | 429 (32) | 523 (19) | < 0.0001 |

| Malignant poorly differentiated neuroendocrine tumors | 168 (12) | 216 (8) | < 0.0001 |

| Other malignant neuroendocrine tumors | 69 (5) | 60 (2) | < 0.0001 |

| Malignant neoplasm of endocrine pancreas | 28 (2) | 31 (1) | 0.022 |

| Region, n (%) | |||

| South | 535 (40) | 1122 (42) | 0.059 |

| North Central | 331 (24) | 574 (21) | |

| Northeast | 268 (20) | 600 (22) | |

| West | 205 (15) | 367 (14) | |

| Unknown | 13 (1) | 28 (1) | |

| Metropolitan statistical area, n (%) | |||

| Urban | 1145 (85) | 2364 (88) | 0.005 |

| Rural | 206 (15) | 327 (12) | |

| Employment status | |||

| Active, full-time | 577 (43) | 1303 (48) | – |

| Active, part-time or seasonal | 3 (0.2) | 20 (1) | |

| Early retiree | 465 (34) | 717 (27) | |

| Other/unknown | 307 (23) | 651 (24) | |

| Health insurance plan type, n (%) | |||

| PPO | 794 (59) | 1654 (61) | 0.001 |

| Comprehensive | 200 (15) | 286 (11) | |

| CDHP/HDHP | 143 (11) | 305 (11) | |

| HMO | 123 (9) | 195 (7) | |

| POS/POS with capitation | 71 (5) | 176 (7) | |

| EPO | 7 (1) | 36 (1) | |

| Missing/unknown | 14 (1) | 39 (1) | |

| Charlson comorbidity index, mean (SD)comorbidities | 1.6 (3.5) | 1.0 (2.9) | < 0.0001 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 411 (30) | 294 (11) | < 0.0001 |

| Flushing | 70 (5) | 46 (2) | < 0.0001 |

| Asthma | 147 (11) | 228 (8) | 0.013 |

| Dyspnea/wheezing | 364 (27) | 546 (20) | < 0.0001 |

| Cardiac palpitations | 105 (8) | 160 (6) | 0.027 |

| Hypotension | 47 (3) | 42 (2) | < 0.0001 |

| Asthenia/fatigue | 424 (31) | 614 (23) | < 0.0001 |

| Dizziness | 184 (14) | 248 (9) | < 0.0001 |

| Intestinal complication | 96 (7) | 94 (3) | < 0.0001 |

| Carcinoid heart disease | 231 (17) | 327 (12) | < 0.0001 |

| Vascular condition | 581 (43) | 899 (33) | < 0.0001 |

| Metastasis/secondary neoplasm | (9) | 428 (16) | < 0.0001 |

| Baseline treatment, n (%) | |||

| Immediate release somatostatin analog | 36 (3) | 25 (1) | < 0.0001 |

| Long-acting somatostatin analog, octreotide | 427 (32) | 429 (16) | < 0.0001 |

| Long-acting somatostatin analog, lanreotide | 18 (1) | 17 (1) | 0.024 |

| Chemotherapy | 84 (6) | 104 (4) | 0.001 |

| Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy | 232 (17) | 277 (10) | < 0.0001 |

| Ablative liver therapy | 3 (0.2) | 20 (1) | 0.038 |

| Targeted therapy | 45 (3) | 46 (2) | 0.001 |

Patients with CSD required greater use of healthcare resources and incurred higher costs than their peers with CS only. More patients with CSD were hospitalized compared to those with CS only (44% vs 25%) and more patients with CSD had ED visits (55% vs 31%) during the study period (Table 2). The total adjusted annual healthcare costs per patient were 50% higher (+ $23865) among those with CSD, driven by outpatient services (+ 56%), prescriptions (+ 48%), ED visits (+ 26%), physician office visits (+ 21%), and hospital admissions (+ 11%; Table 3).

| CSD (n = 1352), mean (SD) | CS only (n = 2691), mean (SD) | P value1 | |

| Hospital admissions | 0.8 (1.8) | 0.4 (1.2) | < 0.0001 |

| Length of hospital stay | 5.3 (17.0) | 2.3 (11.7) | < 0.0001 |

| Physician office visits | 16.3 (9.8) | 12.0 (9.2) | < 0.0001 |

| Emergency room visits | 1.3 (3.1) | 0.6 (1.6) | < 0.0001 |

| Outpatient services | 34.2 (28.4) | 23.1 (23.2) | < 0.0001 |

| Prescription claims | 41.5 (33.1) | 30.5 (27.6) | < 0.0001 |

| CSD (n = 1352), mean (median) | CS only (n = 2691), mean (median) | P value1 | |

| Overall expenditures | $105153 ($63033) | $54701 ($16644) | < 0.0001 |

| Hospitalization | $26361 ($0) | $13247 ($0) | 0.11 |

| Physician office | $2075 ($1653) | $1452 ($1060) | < 0.0001 |

| Emergency room | $2666 ($192) | $994 ($0) | < 0.0001 |

| Outpatient services | $59258 ($31218) | $32014 ($7735) | < 0.0001 |

| Prescriptions | $14792 ($3401) | $6994 ($1361) | < 0.0001 |

This study showed greater healthcare resource use and costs among patients with CSD compared with their peers with CS only. The overall baseline burden of CS was high in both cohorts, and healthcare utilization was driven by both hospitalizations and outpatient services.

These findings are consistent with those of others who have reported the economic burden of CS and CSD. Broder and colleagues recently conducted a similar study in adults < 65 years of age that reported more hospitalizations, ED visits and outpatient visits among patients with CSD compared to those without[15]. Adjusted annual costs were also higher among those with CSD (CSD, $81610 vs CS only, $51719), but lower than those observed in this study (CSD, $105153 vs CS only, $54701). Burton and Lapuerta analyzed medical claims for US adults with CS and inadequate symptom control from somatostatin analog therapy[16]. The proportion of patients with CSD-related ED visits and hospitalizations nearly doubled (9% to 16%) following escalation of somatostatin analog therapy doses, considered a proxy for CS symptom severity, which incurred higher all-cause healthcare costs ($8305 vs $4116 per patient per month). Shen and colleagues reported higher total monthly costs among Medicare beneficiaries who developed CS within the first year of NET diagnosis compared with peers who did not develop CS ($4658 vs $3170)[14]. This average monthly cost was similar to our estimate in CS only patients ($4310), but the authors did not investigate the additional burden of CSD nor was the focus on the working age population. Our study has offered further insights into the burden of CS and CSD in a population of commercially insured working age adults in the United States.

This is the first study to our knowledge that evaluates the burden of CSD-related healthcare resource use and costs among commercially insured, working age adults with a focus on the employer and insurer perspective. In particular, this population may have fewer comorbid causes of morbidity and mortality than those observed in older populations such as Medicare beneficiaries. The database was limited to insured patients with available employment information which does not capture the burden of CS and CSD among uninsured patients or those without some employment-related information available. The retrospective analysis of data collected for insurance claims administration may also be vulnerable to classification issues related to the coding of patient characteristics and medical encounters, which we would not be able to see or account for within this database. For example, the coding of certain neuroendocrine tumor types such as “poorly differentiated” was observed in 11%-23% of patients and yet would be considered an unlikely source of CS based on prior data[11]. The prevalence and incremental costs of CSD among patients with CS may be underestimated since CSD is likely to be captured less often for billing purposes in an administrative claims database than for clinical assessment purposes in medical records.

Patients with NETs and CS suffer substantial burden and require notable healthcare resources with associated costs, particularly in the presence of CSD. This condition negatively impacts patients, employers, and the healthcare system. Timely identification and management of CSD in patients with CS may reduce the burden of this debilitating and resource-intensive condition.

Carcinoid syndrome (CS) in patients with neuroendocrine tumors has been shown to bear substantial economic costs to patients and healthcare systems; however, the incremental burden of CS diarrhea (CSD) has not been well characterized in the literature. Since patients with CSD are most often of working age, it is important to understand the direct costs of CSD from a population health management perspective. This study aims to provide detail and context related to the direct costs of CSD on insured working age adults in the United States.

Quantifying the economic burden of CSD in this population is important for setting healthcare priorities and allocating healthcare resources in an appropriate and efficient manner. Patients with CSD may be underserved due to a lack of information and insight regarding the burden of CSD overall, and payers need to understand the scope of economic burden of CSD in order to design effective policies and programs. Future research may validate these findings and apply similar methods to additional health system configurations such as integrated delivery networks, single payer systems, and other approaches to population health management found worldwide.

We aimed to quantify the incremental economic burden of CSD compared with patients who had CS but no CSD. The differentiation of CSD within the broader scope of CS costs is important for resource allocation and policy decisions, and has not been well studied. This objective allows population health managers to more clearly examine the additive costs that are specific to CSD in this patient population, where such discrimination of costs was not previously possible. Future research may build upon these insights and expand them to include indirect costs such as work productivity burden and other important factors.

We conducted a retrospective study of CS patients with and without CSD as identified in the IBM® MarketScan® Database between 2014–2016, including the Medicare Supplemental Coordination of Benefits database. Patients had to have at least 1 medical claim for CS and continuous health plan enrollment for at least 12 mo prior to their first CS diagnosis, and for at least 30 d after. We excluded patients with documented claims for acromegaly, and those who participated in a clinical trial during the study period. Measures of healthcare resource use and costs were compared between patients with and without CSD, including Emergency Department (ED) visits, hospital admissions and length of stay, physician office visits, outpatient services, and prescription claims, using univariate and multivariate analyses to evaluate associations of CSD with healthcare resource use and costs, controlling for baseline characteristics. The methods applied in this analysis allowed us to distinguish the direct costs among patients with CS “only” from their peers had CS and CSD. This approach allowed us to characterize the additive, or incremental healthcare-related costs of CSD in the context of a patient population that was as similar as possible to those with CSD.

Our study identified 4043 patients with CS to be included in the analysis, 1352 with CSD and 2691 with CS only. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were similar between groups except that patients with CSD were older, had more comorbidities, and received more somatostatin analog therapy at baseline. Overall, patients with CSD required more healthcare resources and incurred higher costs than their peers with CS only. In particular, patients with CSD had more hospitalizations (44% vs 25%) and Emergency Department visits (55% vs 31%). When adjusted for baseline demographic and clinical characteristics, patients with CSD had higher mean healthcare resource use across all components of care, including hospital admissions (0.8 vs 0.4) and the mean length of stays (5.3 d vs 2.3 d), physician office visits (16.3 vs 12.0), Emergency Department visits (1.3 vs 0.6), outpatient services (34.2 vs 23.1), and prescription claims (41.5 vs 30.5). The total adjusted annual healthcare costs per patient were 50% higher (+ $23865) among those with CSD, driven by outpatient services (+ 56%), prescriptions (+ 48%), ED visits (+ 26%), physician office visits (+ 21%), and hospital admissions (+ 11%). These findings provide quantifiable differences in direct costs between patients with CS “only” and their peers who also have CSD. The increased costs observed across all avenues of care are indicative of the increased burden of CSD on patients and the healthcare resources needed to provide adequate care for this disruptive and damaging condition. Further research may validate these findings and investigate similar incremental costs in other healthcare settings.

This study demonstrated that the costs of managing CSD are greater than those related to CS alone among insured working age adults in the United States, allowing population health managers to more intimately understand the incremental economic burden of CSD and to develop policies and programs accordingly. The methods applied in this study may be replicated or adopted to other data sources and healthcare settings to continue to characterize the additive costs of CSD in this predominantly working age population. This study provides a clear illustration of costs from the perspective of the employers and insurers, which is essential to effective policy and practice for this relatively young, active patient population. Timely identification and appropriate management of CSD may not only alleviate the clinical and humanistic burden of CSD to these patients, but may also reduce the economic burden of CSD to payers and population health managers.

Patients with neuroendocrine tumors and CS require substantial healthcare resources to manage this condition, which are greatest among those who also have CSD. Supporting the timely identification and management of CSD should be a priority for population health managers, as this condition has been shown to negatively impact patients, employers, and the healthcare system. Future research may validate and extend these findings, and investigate indirect costs such as the impact of CS and CSD on quality of life, work productivity, and caregivers.

This study was sponsored by Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Medical writing support was provided by Jeff Frimpter, MPH, and Kristi Boehm, MS, ELS.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Leontiadis GI, Rocha R S-Editor: Wang J L-Editor: A E-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Turaga KK, Kvols LK. Recent progress in the understanding, diagnosis, and treatment of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:113-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Yao JC, Hassan M, Phan A, Dagohoy C, Leary C, Mares JE, Abdalla EK, Fleming JB, Vauthey JN, Rashid A, Evans DB. One hundred years after "carcinoid": epidemiology of and prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35,825 cases in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3063-3072. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3022] [Cited by in RCA: 3245] [Article Influence: 190.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Dasari A, Shen C, Halperin D, Zhao B, Zhou S, Xu Y, Shih T, Yao JC. Trends in the Incidence, Prevalence, and Survival Outcomes in Patients With Neuroendocrine Tumors in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1335-1342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1510] [Cited by in RCA: 2489] [Article Influence: 311.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 4. | Öberg K, Knigge U, Kwekkeboom D, Perren A; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Neuroendocrine gastro-entero-pancreatic tumors: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2012;23 Suppl 7:vii124-vii130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 307] [Cited by in RCA: 337] [Article Influence: 28.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hallet J, Law CH, Cukier M, Saskin R, Liu N, Singh S. Exploring the rising incidence of neuroendocrine tumors: a population-based analysis of epidemiology, metastatic presentation, and outcomes. Cancer. 2015;121:589-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 446] [Cited by in RCA: 612] [Article Influence: 55.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Lewis MA, Hobday TJ. Treatment of neuroendocrine tumor liver metastases. Int J Hepatol. 2012;2012:973946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | McCormick D. Carcinoid tumors and syndrome. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2002;25:105-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rorstad O. Prognostic indicators for carcinoid neuroendocrine tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. J Surg Oncol. 2005;89:151-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | DeVita V. et al (eds)Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology (10th ed). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014. . |

| 11. | Halperin DM, Shen C, Dasari A, Xu Y, Chu Y, Zhou S, Shih YT, Yao JC. Frequency of carcinoid syndrome at neuroendocrine tumour diagnosis: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:525-534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 259] [Article Influence: 32.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Anthony L, Ervin C, Lapuerta P, Kulke MH, Kunz P, Bergsland E, Hörsch D, Metz DC, Pasieka J, Pavlakis N, Pavel M, Caplin M, Öberg K, Ramage J, Evans E, Yang QM, Jackson S, Arnold K, Law L, DiBenedetti DB. Understanding the Patient Experience with Carcinoid Syndrome: Exit Interviews from a Randomized, Placebo-controlled Study of Telotristat Ethyl. Clin Ther. 2017;39:2158-2168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Singh S, Granberg D, Wolin E, Warner R, Sissons M, Kolarova T, Goldstein G, Pavel M, Öberg K, Leyden J. Patient-Reported Burden of a Neuroendocrine Tumor (NET) Diagnosis: Results From the First Global Survey of Patients With NETs. J Glob Oncol. 2017;3:43-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Shen C, Chu Y, Halperin DM, Dasari A, Zhou S, Xu Y, Yao JC, Shih YT. Carcinoid Syndrome and Costs of Care During the First Year After Diagnosis of Neuroendocrine Tumors Among Elderly Patients. Oncologist. 2017;22:1451-1462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Broder MS, Chang E, Romanus D, Cherepanov D, Neary MP. Healthcare and economic impact of diarrhea in patients with carcinoid syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:2118-2125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Burton T, Lapuerta P. Economic analysis of inadequate symptom control in carcinoid syndrome in the United States. Future Oncol. 2018;14:2361-2370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |