Published online Nov 28, 2019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i44.6541

Peer-review started: August 16, 2019

First decision: October 14, 2019

Revised: October 24, 2019

Accepted: November 13, 2019

Article in press: November 13, 2019

Published online: November 28, 2019

Processing time: 104 Days and 8.1 Hours

According to the latest American Joint Committee on Cancer and Union for International Cancer Control manuals, cystic duct cancer (CC) is categorized as a type of gallbladder cancer (GC), which has the worst prognosis among all types of biliary cancers. We hypothesized that this categorization could be verified by using taxonomic methods.

To investigate the categorization of CC based on population-level data.

Cases of biliary cancers were identified from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results 18 registries database. Together with routinely used statistical methods, three taxonomic methods, including Fisher’s discriminant, binary logistics and artificial neuron network (ANN) models, were used to clarify the categorizing problem of CC.

The T staging system of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma [a type of extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (EC)] better discriminated CC prognosis than that of GC. After adjusting other covariates, the hazard ratio of CC tended to be closer to that of EC, although not reaching statistical significance. To differentiate EC from GC, three taxonomic models were built and all showed good accuracies. The ANN model had an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.902. Using the three models, the majority (75.0%-77.8%) of CC cases were categorized as EC.

Our study suggested that CC should be categorized as a type of EC, not GC. Aggressive surgical attitude might be considered in CC cases, to see whether long-term prognosis could be immensely improved like the situation in EC.

Core tip: In the latest American Joint Committee on Cancer and Union for International Cancer Control manuals, cystic duct cancer (CC) is categorized as a type of gallbladder cancer, yet not verified by direct epidemiological evidence in previous studies. Our study used taxonomic methods to analyze population-based big data, including Fisher’s discriminant, binary logistics and artificial neuron network models. By using these three models, our study proved that CC is better to be deemed and treated as a kind of extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

- Citation: Yu TN, Mao YY, Wei FQ, Liu H. Cystic duct cancer: Should it be deemed as a type of gallbladder cancer? World J Gastroenterol 2019; 25(44): 6541-6550

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v25/i44/6541.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i44.6541

Cystic duct cancer (CC) is a rare type of biliary cancer which arises in the conjunction between the gallbladder and the extraheptic bile duct[1]. By Farrar[2] in 1951, CC was defined based on the following three criteria: “(1) The growth must be restricted to the cystic duct; (2) There must be no neoplastic process in the gallbladder, hepatic or common bile ducts; and (3) A histological examination of the growth must confirm the presence of carcinoma cells”. Unlike other biliary neoplasms, the incidence of CC is extremely low (0.03%-0.05%[3]), and previous studies on this disease were focusing on single cases[4-7] or very small-volume series (less than 10 cases)[8,9]. As a consequence, the clinical characteristics of CC remain largely unknown. According to the 8th American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC)[10] and 9th Union for International Cancer Control (UICC)[11] manuals, CC is categorized as a type of gallbladder cancer (GC), which has the worst prognosis among all types of biliary tumor[12,13]. However, this categorization lacks verification by direct epidemiological evidence until now.

In the field of botany, a well-known statistical tool is the Fisher’s linear discriminant analysis, which was invented by Sir Ronald Aylmer Fisher[14] and initially used to make optimum categorization for three types of iris flowers, namely, Setosa, Versicolour and Virginica. In the current study, besides routinely used statistical tools, we applied to use this taxonomic method together with binary logistics and artificial neuron network (ANN) models, to clarify the categorizing problem of CC. To our knowledge, this is the first study attempting to re-categorize CC using population based data.

Eligible cases of CC, GC and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (EC) diagnosed between 2006 and 2015 were obtained from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) 18 registries database (last submission in November, 2017). CC or GC cases were retrieved with their terms in “CS schema v0204+”; while EC cases were retrieved with a combined term of “BileductsPerihilar” and “BileductsDistal”. All cases reviewed had their pathologies microscopically confirmed, their ages known, and their biological behavior classified as malignant.

For each case, ten variables were evaluated as follows: Sex, age at diagnosis, year of diagnosis, marital status at diagnosis, race recode, SEER historical stage A, tumor size, Rx Summ-Surg Prim Site (1998+), CHDSA region and histology recode-broad grouping.

For marital status, the values of single, separated, divorced, widowed and unmarried or domestic partner were defined as “unmarried”. For Rx Summ-Surg Prim Site (1998+)[15], which means surgical procedure, a value of 0 was defined as “no operation”; values from 10 to 30, and of 50 were defined as “biopsy/ partial resection”; a value of 40 was defined as “total resection”; and a value of 60 was defined as “radical resection”. For histology recode, a value of 8140-8389 was defined as “adenocarcinoma”, while other values were defined as “others”.

Routine statistical methods: The Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical data to compare the distributions of variables between CC, GC and EC. The Mann-Whitney U test was used for continuous variables. The 1, 3 and 5-year overall survival (OS) and cancer specific survival (CSS) rates were calculated by the method of life table. CC cases were divided into T1-2 group and T3-4 group by the current T staging system for GC or EC, respectively (Supplementary table 1), and the prognosis of different groups was compared by the log-rank test. The COX proportional model was utilized to analyze the whole population of CC, GC and EC, and identify the independent prognostic factors for OS and CSS.

Methods to categorize CC: Three steps were required to categorize CC. First, three models were built. All cases of GC and EC were randomly partitioned, and then divided into either a training (70%) or testing group (30%). Three models were constructed to differentiate between GC and EC. In Fisher’s linear discriminant model, the importance of variables was evaluated by the absolute values of their coefficients in a structure matrix. In binary logistic model, multivariate analysis was performed, and P-value was calculated for each variable. In ANN model, a multilayer perceptron neural network was utilized, and normalized importance was calculated for each variable.

In the next step, the models were evaluated. Accuracies were calculated for the training, testing and whole groups, respectively, and good models generally had these three values very close. The power of a model was also evaluated by the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC). Generally, AUROC indicated a model of “good” accuracy at a value between 0.75 and 1.00, of “fair” accuracy at a value between 0.60 and 0.75, and of “poor” accuracy at a value under 0.60.

Finally, CC cases were categorized. Each case of CC would be categorized as GC or EC using the three models. Overall agreement of results of the three models was evaluated by an online Kappa test calculator[16] as well as the McNemar’s test.

Between 2006 and 2015, the SEER database recognized a total of 71 cases of CC. However, a certain proportion of cases had missing values and could not be utilized for analysis for all aims. Regarding the analysis of 1, 3 and 5-year survival and T stage, the included cases should have valid data for the variables of “CS extension”, “Survival months” and “Vital status recode” (for OS, or “SEER cause-specific classification” for CSS). Consequently, 65 CC cases were analyzed for OS and 56 were analyzed for CSS. In other analyses (comparison of clinical characteristics between different diseases, COX analysis, building models and categorization of CC), all cases involved should have valid data for 10 variables from sex to histology, and cases with missing data could not be produced. Consequently, a total of 36 CC cases were analyzed for the aim of categorization, together with 4878 GC cases and 3295 EC cases. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and the IBM SPSS version 22.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States) was utilized for all analyses.

Table 1 shows the comparison of the clinical characteristics between CC, GC and EC. Five variables were found to be statistically different between CC and GC, including sex, tumor size, SEER historical stage, surgical procedure and histology (P < 0.05). However, only one variable (surgical procedure) was found to be different between CC and EC (P < 0.05).

| Variable | No. (%) of patients | P value | |||

| GC (n = 4878) | EC (n = 3295) | CC (n = 36) | CC vs GC | CC vs EC | |

| Sex | < 0.001a | 0.067 | |||

| Male | 1528 (31.3) | 1880 (57.1) | 26 (72.2) | ||

| Female | 3350 (68.7) | 1415 (42.9) | 10 (27.8) | ||

| Age at diagnosis (median) | 71 | 69 | 66.5 | 0.059 | 0.161 |

| Year of diagnosis | 0.487 | 0.492 | |||

| 2006 to 2010 | 2041 (41.8) | 1377 (41.8) | 13 (36.1) | ||

| 2011 to 2015 | 2837 (58.2) | 1918 (58.2) | 23 (63.9) | ||

| Marital status | 0.269 | 0.948 | |||

| Not married | 2348 (48.1) | 1264 (38.4) | 14 (38.9) | ||

| Married | 2530 (51.9) | 2031 (61.6) | 22 (61.1) | ||

| Race | 0.703 | 0.330 | |||

| White | 3604 (73.9) | 2529 (76.8) | 25 (69.4) | ||

| Black | 683 (14.0) | 246 (7.5) | 5 (13.9) | ||

| Others | 591 (12.1) | 520 (15.8) | 6 (16.7) | ||

| Tumor size (median) | 33 | 25 | 25.5 | 0.005a | 0.195 |

| SEER historical stage | < 0.001a | 0.326 | |||

| Localized | 1934 (39.6) | 522 (15.8) | 3 (8.3) | ||

| Regional | 1150 (23.6) | 2098 (63.7) | 27 (75.0) | ||

| Distant | 1794 (36.8) | 675 (20.5) | 6 (16.7) | ||

| Surgical procedure | < 0.001a | 0.047a | |||

| No operation | 1014 (20.8) | 1468 (44.6) | 8 (22.2) | ||

| Biopsy/partial resection | 833 (17.1) | 535 (16.2) | 10 (27.8) | ||

| Total resection | 2490 (51.0) | 417 (12.7) | 6 (16.7) | ||

| Radical resection | 541 (11.1) | 875 (26.6) | 12 (33.3) | ||

| Region | 0.928 | 0.865 | |||

| Alaska | 10 (0.2) | 6 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| East | 1705 (35.0) | 1104 (33.5) | 14 (38.9) | ||

| Northern plains | 441 (9.0) | 301 (9.1) | 5 (13.9) | ||

| Pacific coast | 1858 (51.1) | 1346 (41.9) | 16 (44.4) | ||

| Southwest | 149 (4.1) | 86 (3.4) | 1 (2.8) | ||

| Histology | 0.042a | 0.725 | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 4152 (85.1) | 3086(93.7) | 35 (97.2) | ||

| Others | 726 (14.9) | 209 (6.3) | 1 (2.8) | ||

The 1, 3 and 5-year survival rates of CC were 50%, 27% and 12% for OS, and 51%, 30% and 20% for CSS, respectively. The median survival time was 13.0 months for both OS and CSS.

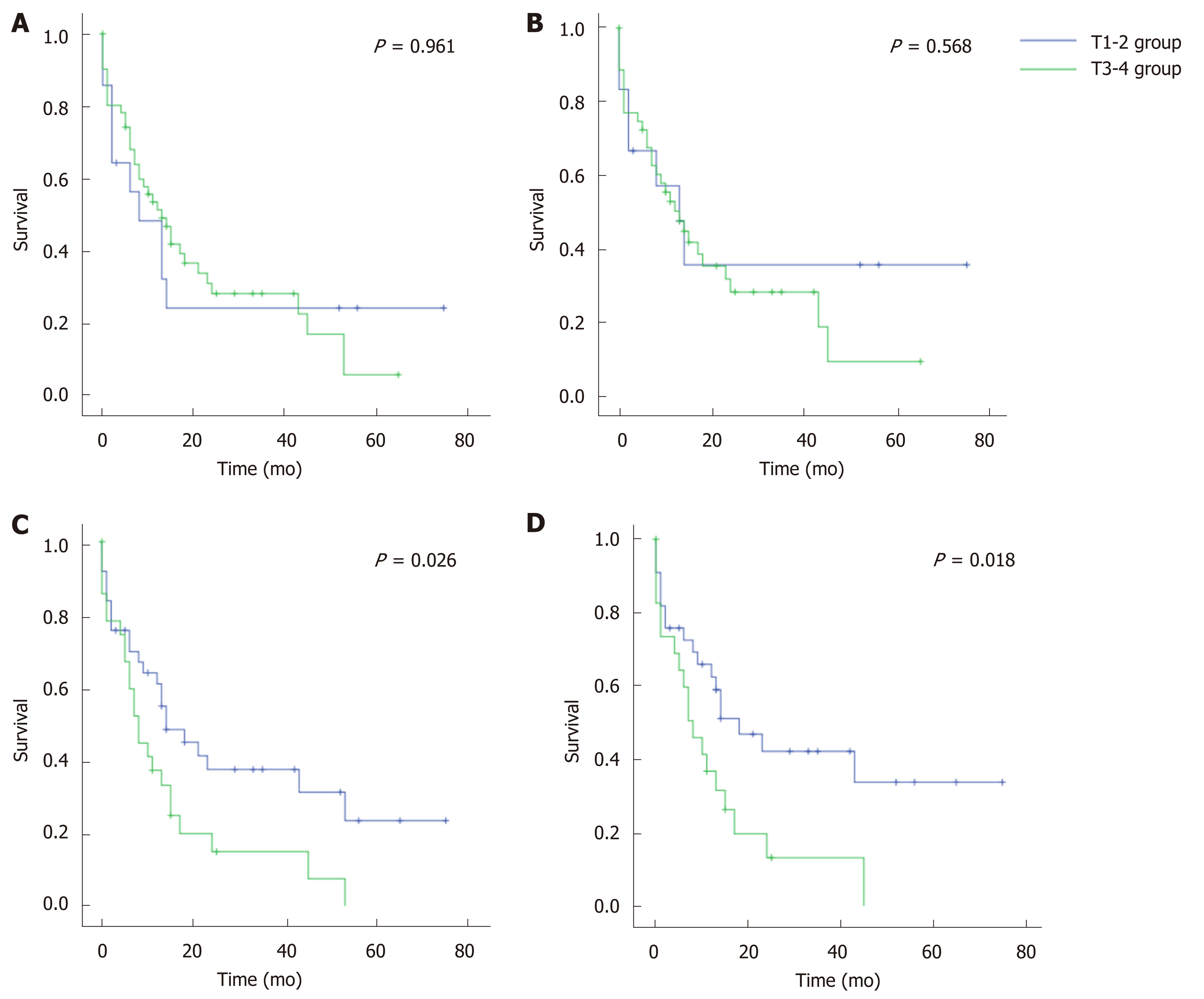

All CC cases were divided into T1-2 and T3-4 groups according to the T staging system of GC or EC (Figure 1). Based on the GC system, the prognosis was similar between the T1-2 and T3-4 groups (P = 0.961 for OS, and 0.568 for CSS). Comparatively, the EC system (perihilar cholangiocarcinoma) showed statistically different prognoses between the T1-2 and T3-4 groups (P < 0.05 for both OS and CSS). Therefore, the T staging system of EC better discriminated CC prognosis than that of GC.

In COX analysis for the whole population of biliary cancer cases, nine variables were found as independent prognostic factors for OS and CSS, including sex, age at diagnosis, year of diagnosis, marital status, SEER historical stage, tumor size, surgical procedure, histology and disease (Table 2, P < 0.05). By using CC as the reference (1.000), the hazard ratio (HR) for OS was 1.238 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.813 to 1.884, P = 0.320] for EC but 1.494 (95%CI: 0.980 to 2.279, P = 0.062) for GC. Regarding CSS, the HR was 1.124 (95%CI: 0.706 to 1.789, P = 0.623) for EC but 1.348 (95%CI: 0.845 to 2.151, P = 0.210) for GC. Compared with GC, the HR of EC tended to be closer to that of CC, although not reaching statistical significance (P > 0.05).

| Variable | OS | CSS | ||||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Female | 0.886 | 0.838 to 0.938 | < 0.001a | 0.895 | 0.838 to 0.957 | 0.001a |

| Age at diagnosis | 1.025 | 1.022 to 1.027 | < 0.001a | 1.022 | 1.019 to 1.025 | < 0.001a |

| Year of diagnosis | ||||||

| 2006 to 2009 | Ref | Ref | ||||

| 2010 to 2013 | 0.938 | 0.889 to 0.990 | 0.019a | 0.927 | 0.870 to 0.987 | 0.018a |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Unmarried | 0.839 | 0.794 to 0.887 | < 0.001a | 0.855 | 0.801 to 0.912 | < 0.001a |

| Race | 0.110 | 0.258 | ||||

| White | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Black | 0.929 | 0.857 to 1.007 | 0.074 | 0.941 | 0.856 to 1.033 | 0.200 |

| Other | 1.042 | 0.956 to 1.135 | 0.347 | 1.048 | 0.948 to 1.158 | 0.359 |

| Tumor size | 1.002 | 1.001 to 1.002 | < 0.001a | 1.003 | 1.002 to 1.004 | < 0.001a |

| SEER historical stage | < 0.001a | < 0.001a | ||||

| Distant | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Regional | 0.342 | 0.316 to 0.370 | < 0.001a | 0.277 | 0.252 to 0.306 | < 0.001a |

| Localized | 0.642 | 0.599 to 0.668 | < 0.001a | 0.613 | 0.566 to 0.664 | < 0.001a |

| Surgical procedure | < 0.001a | < 0.001a | ||||

| No operation | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Partial resection | 0.412 | 0.378 to 0.449 | < 0.001a | 0.395 | 0.356 to 0.438 | < 0.001a |

| Total resection | 0.403 | 0.373 to 0.435 | < 0.001a | 0.383 | 0.350 to 0.419 | < 0.001a |

| Radical resection | 0.359 | 0.330 to 0.391 | < 0.001a | 0.352 | 0.318 to 0.388 | < 0.001a |

| Region | 0.934 | 0.883 | ||||

| Alaska | Ref | Ref | ||||

| East | 1.081 | 0.623 to 1.878 | 0.781 | 1.055 | 0.593 to 1.878 | 0.855 |

| Northern Plains | 1.127 | 0.646 to 1.967 | 0.673 | 1.116 | 0.623 to 2.001 | 0.711 |

| Pacific coast | 1.088 | 0.628 to 1.885 | 0.764 | 1.052 | 0.593 to 1.867 | 0.863 |

| Southwest | 1.090 | 0.619 to 1.920 | 0.766 | 1.06 | 0.584 to 1.926 | 0.847 |

| Histology | ||||||

| Adenocarcinoma | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Others | 1.186 | 1.094 to 1.285 | < 0.001a | 1.215 | 1.107 to 1.334 | < 0.001a |

| Disease | < 0.001a | < 0.001a | ||||

| CC | Ref | Ref | ||||

| GC | 1.494 | 0.980 to 2.279 | 0.062 | 1.348 | 0.845 to 2.151 | 0.210 |

| EC | 1.238 | 0.813 to 1.884 | 0.320 | 1.124 | 0.706 to 1.789 | 0.623 |

Three models were constructed to differentiate GC from EC (Table 3). In the Fisher’s linear discriminant model, the most important three variables (highest absolute values) were sex (0.479), SEER historical stage (0.665) and surgical procedure (-0.238). In the binary logistic model, six variables had statistical significance (P < 0.05), including sex, age at diagnosis, tumor size, SEER historical stage, surgical procedure and histology. In the ANN model, the variables with the highest value of normalized importance were tumor size (71.8%), SEER historical stage (80.4%) and surgical procedure (100.0%).

| Fisher’s linear discriminant | Binary logistic | ANN | |

| Coefficient in structure matrix | P value | Normalized importance (%) | |

| Variable | |||

| Sex | 0.479b | < 0.001a | 26.1 |

| Age at diagnosis | -0.091 | < 0.001a | 44.1 |

| Year of diagnosis | 0.018 | 0.508 | 12.4 |

| Martial status | 0.164 | 0.088 | 7.1 |

| Race | -0.011 | 0.426 | 22 |

| Tumor size | -0.215 | < 0.001a | 71.8c |

| SEER historical stage | 0.665b | < 0.001a | 80.4c |

| Surgical procedure | -0.238b | < 0.001a | 100.0c |

| Region | 0.011 | 0.315 | 25.9 |

| Histology | 0.221 | < 0.001a | 26.6 |

| Model performance | |||

| Accuracy (%) | |||

| Training sample (n = 5743) | 70.1 | 72.7 | 82.2 |

| Testing sample (n = 2430) | 69.3 | 73.6 | 81.9 |

| Whole (n = 8173) | 69.9 | 73.0 | 82.1 |

| AUROC (95% CI) | 0.781 (0.771-0.791) | 0.785 (0.775-0.795) | 0.902 (0.895-0.908) |

| Categorization in CC cases | |||

| Categorized as GC (%) | 8 (22.2) | 9 (25.0) | 8 (22.2) |

| Categorized as EC (%) | 28 (77.8) | 27 (75.0) | 28 (77.8) |

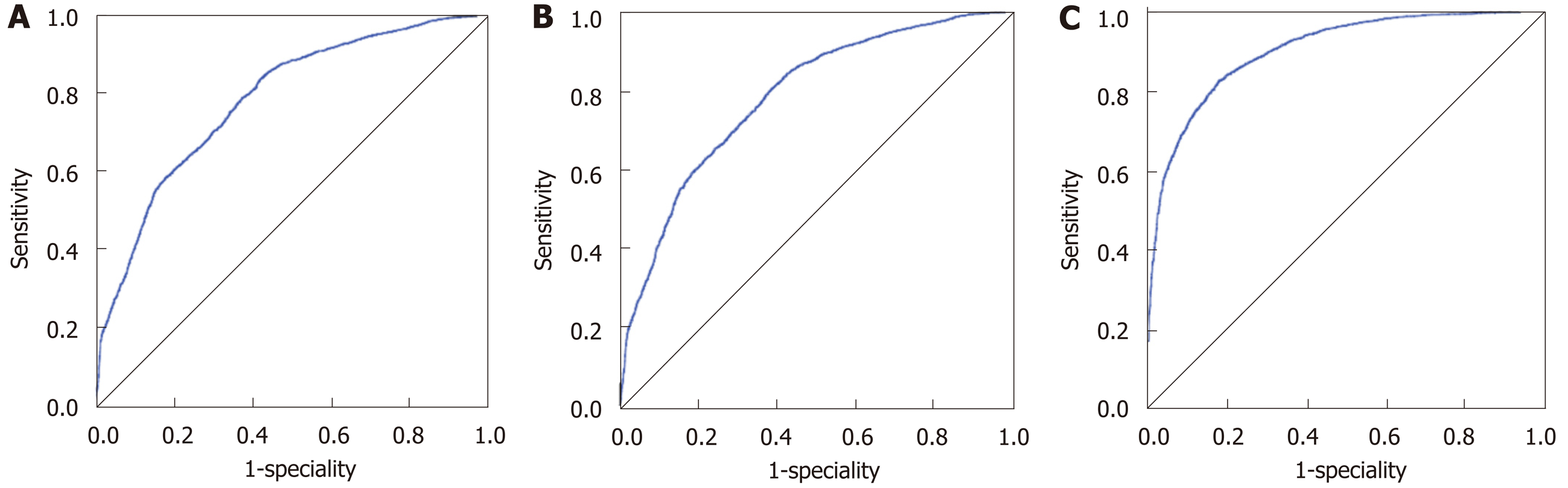

The accuracies of the Fisher’s linear discriminant, binary logistic and ANN models were 69.9%, 73.0% and 82.1%, respectively. And for each model, the accuracies in the training, testing and whole populations were close. The AUROCs of the aforementioned three models were 0.781 (95%CI: 0.771-0.791), 0.785 (95%CI: 0.775-0.795) and 0.902 (95%CI: 0.895-0.908), all of which suggested “good” accuracies (Figure 2). The ANN model had the best categorizing power.

Based on the ANN model, the majority (77.8%, 28/36) of CC cases were categorized as EC, the percentage of which was similar to those obtained based on the Fisher’s (77.8%) and binary logistic (75.0%) models (Table 3). The three categorizing results had an overall agreement of 85.19%, and Mcnemer tests between each two models showed no statistical differences (P = 1.000).

CC was categorized as a type of GC in the latest AJCC[10] and UICC[11] manuals. However, our study argued with their practice, mainly based on two statistical findings: (1) Compared with the staging system of GC, the T staging system of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma (a type of EC) better discriminated the prognosis of CC. Unlike the staging system of lymphatic or distant metastasis (N or M), the T staging system was obviously different in EC and GC. That is, a lesion of GC would be staged as T3-4 when it involved the serosa of the biliary wall, while a lesion of EC would not be staged as T3-4 only when it invaded the portal vein, artery, or the second-order biliary system[10,11]. In this study, when the GC staging system was used, no prognostic differences were observed between the T1-2 and T3-4 groups. However, the difference was of statistical significance when the EC system was used (P < 0.05); and (2) The majority of CC cases (75.0%-77.8%) were categorized as EC by using the three taxonomic models. The three models used, including the Fisher’s discriminant, binary logistics and ANN models, were constructed based on big data of over 8000 biliary cancer cases. Based on the AUROC, all models had “good” categorizing power, and the ANN model even had a value of over 0.90.

To our knowledge, this study provided the first population-level evidence for the categorizing problem of CC. In the 6th AJCC manual, CC was included in the EC chapter, but was classified as a type of GC since the 7th edition[17]. This practice was agreed by a recent single-center study by Nakanishi et al[18]. However, in that study, the definition of CC seemed to be not strict, because the incidence of CC was too high and even exceeded that of GC (47 vs 43) during the follow-up period. Besides, a large proportion of cases were at very advanced stage (with invasion to the duodenum, artery or portal vein), possibly attributed to the fact that some GC cases were misjudged as CC due to difficulty in detecting primary lesions.

Interestingly, in previous publications, there were also some clues to suggest the difference between CC and ordinary GC. In the study of Nishio[19], “GC cases” with common bile duct invasion (most of which were CC) had a favorable 5-year survival rate of over 20%, which was much better than the commonly expected prognosis in T3 stage GC cases. In the study of Ozden[20], “GC cases” with their lesion centers located in the cystic ducts (actually CC) had some unique clinical features, including their approximately equal proportion of sex, advanced T stage, and a lower than expected frequency of lymph node metastasis, which more resembled EC.

However, the surgical attitude for EC and GC was different in clinical practice. EC (especially for perihiliar cholangiocarcinoma) was considered as being worthy of extensive resection even at the expense of increased complication rates (biliary fistula, etc.), since a successful R0 resection could drastically improve long-term prognosis[21], and transplantation could be considered in well-selected patients[22]. Comparatively, in advanced GC cases, aggressive surgical resection did not show concrete survival benefits, including combined common bile duct resection[23] and extended regional lymphadenectomy[24]. According to a recent United States population-level study[25], extended resection alone in GC provided a worse prognosis than simple removal of the gallbladder plus adjuvant chemotherapy. The similarity between CC and EC suggested the rationality that CC should not be treated like GC. In other words, extended surgical resection could be attempted in CC even at advanced stage, to see whether this treatment could immensely improve the prognosis like the situation in EC.

There are several limitations to this study. First, the variable of lymphatic status was not analyzed. In the SEER database, most of biliary cases had their lymphatic status unknown, and few cases had their harvested lymph nodes more than three, which was the minimum number to accurately evaluate lymphatic metastasis[26]. Therefore, although the pattern of lymphatic metastasis was different among CC, GC and EC[20,27,28], inclusion of this variable had modest value to increase performance of models. Second, whole genome sequencing also could help to clarify the categorization of CC. However, due to the extreme rarity of CC specimens, this molecular evidence is currently not available.

In conclusion, our study argued with categorization of CC in the current AJCC and UICC manuals, and suggested that CC should be categorized as a type of EC. Extended surgical resection might be considered in CC cases, to see whether long-term prognosis could be immensely improved like the situation in EC.

According to the current guidelines, cystic duct cancer (CC) is categorized as a type of gallbladder cancer (GC), which has the worst prognosis among all types of biliary cancers.

In previous studies, no direct epidemiological evidence verified that CC was more similar to GC, rather than extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (EC).

This study aimed to investigate the categorization of CC based on population-level data.

We used three taxonomic methods for analysis, including Fisher’s discriminant, binary logistics and artificial neuron network models.

The T staging system of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma (a type of EC) better discriminated CC prognosis than that of GC. By using the three taxonomic models, the majority (75.0%-77.8%) of CC cases were categorized as EC.

Our study suggested that CC should be categorized as a type of EC, not GC.

Aggressive surgical attitude might be considered in CC cases, to see whether long-term prognosis could be immensely improved like the situation in EC. Future studies with larger sample size are needed.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Michalinos A S-Editor: Wang J L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Stewart HL, Lieber MM, Morgan DR. Carcinoma of extrahepatic bile ducts. Arch Surg. 1940;41:662-713. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | FARRAR DA. Carcinoma of the cystic duct. Br J Surg. 1951;39:183-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Phillips SJ, Estrin J. Primary adenocarcinoma in a cystic duct stump. Report of a case and review of the literature. Arch Surg. 1969;98:225-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Eum JS, Kim GH, Park CH, Kang DH, Song GA. A remnant cystic duct cancer presenting as a duodenal submucosal tumor. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:975-6; discussion 976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Maeda T, Natsume S, Kato T, Hiramatsu K, Aoba T, Matsubara H. Early cystic duct cancer with widely spreading carcinoma in situ in the gallbladder: A case report. Jjba. 2015;29:261-265. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Komori S, Tsuchiya J, Kumazawa I, Kawagoe H, Nishio K, Misao Y. Preoperative diagnosis of an asymptomatic cancer restricted to the cystic duct. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2014;5:354-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bains L, Kaur D, Kakar AK, Batish A, Rao S. Primary carcinoma of the cystic duct: a case report and review of classifications. World J Surg Oncol. 2017;15:30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chan KM, Yeh TS, Tseng JH, Liu NJ, Jan YY, Chen MF. Clinicopathological analysis of cystic duct carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005;52:691-694. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Kubota K, Kakuta Y, Inayama Y, Yoneda M, Abe Y, Inamori M, Kirikoshi H, Saito S, Nakajima A, Sugimori K, Matuo K, Kazunaga T, Shimada H. Clinicopathologic study of resected cases of primary carcinoma of the cystic duct. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55:1174-1178. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, Byrd DR, Brookland RK, Washington MK, Gershenwald JE, Compton CC, Hess KR, Sullivan DC, Jessup JM, Brierley JD, Gaspar LE, Schilsky RL, Balch CM, Winchester DP, Asare EA, Madera M, Gress DM, Meyer LR. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer International Publishing. 2018;303. |

| 11. | O'Sullivan B, Brierley JD, D'Cruz AK, Fey MF, Pollock R, Vermorken JB, Shao HH. UICC Manual of Clinical Oncology. 9th ed. Wiley-Blackwell. 2015;267. |

| 12. | Yamaguchi K, Nishihara K, Tsuneyoshi M. Carcinoma of the cystic duct. J Surg Oncol. 1991;48:282-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chijiiwa K, Torisu M. Primary carcinoma of the cystic duct. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1993;16:309-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fisher RA. THE USE OF MULTIPLE MEASUREMENTS IN TAXONOMIC PROBLEMS. Annals of Human Genetics. 1936;7:179-188. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8484] [Cited by in RCA: 3648] [Article Influence: 280.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | SEER Program Coding and Staging Manual 2016. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/manuals/2016/AppendixC/Surgery_Codes_Other_Sites_2016.pdf. |

| 16. | Online Kappa Calculator. Available from: http://justusrandolph.net/kappa/. |

| 17. | Collaborative Stage Data Set (Cystic Duct C240). Available from: http://web2.facs.org/cstage0205/cysticduct/CysticDuctschema.html. |

| 18. | Nakanishi Y, Tsuchikawa T, Okamura K, Nakamura T, Noji T, Asano T, Tanaka K, Shichinohe T, Mitsuhashi T, Hirano S. Clinicopathological features and prognosis of advanced biliary carcinoma centered in the cystic duct. HPB (Oxford). 2018;20:28-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Nishio H, Ebata T, Yokoyama Y, Igami T, Sugawara G, Nagino M. Gallbladder cancer involving the extrahepatic bile duct is worthy of resection. Ann Surg. 2011;253:953-960. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ozden I, Kamiya J, Nagino M, Uesaka K, Oda K, Sano T, Kamiya S, Nimura Y. Cystic duct carcinoma: a proposal for a new "working definition". Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2003;387:337-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ribero D, Amisano M, Lo Tesoriere R, Rosso S, Ferrero A, Capussotti L. Additional resection of an intraoperative margin-positive proximal bile duct improves survival in patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2011;254:776-81; discussion 781-3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ethun CG, Lopez-Aguiar AG, Anderson DJ, Adams AB, Fields RC, Doyle MB, Chapman WC, Krasnick BA, Weber SM, Mezrich JD, Salem A, Pawlik TM, Poultsides G, Tran TB, Idrees K, Isom CA, Martin RCG, Scoggins CR, Shen P, Mogal HD, Schmidt C, Beal E, Hatzaras I, Shenoy R, Cardona K, Maithel SK. Transplantation Versus Resection for Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma: An Argument for Shifting Treatment Paradigms for Resectable Disease. Ann Surg. 2018;267:797-805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lim JH, Chong JU, Kim SH, Park SW, Choi JS, Lee WJ, Kim KS. Role of common bile duct resection in T2 and T3 gallbladder cancer patients. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2018;22:42-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Niu GC, Shen CM, Cui W, Li Q. Surgical treatment of advanced gallbladder cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2015;38:5-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kasumova GG, Tabatabaie O, Najarian RM, Callery MP, Ng SC, Bullock AJ, Fisher RA, Tseng JF. Surgical Management of Gallbladder Cancer: Simple Versus Extended Cholecystectomy and the Role of Adjuvant Therapy. Ann Surg. 2017;266:625-631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Jensen EH, Abraham A, Jarosek S, Habermann EB, Al-Refaie WB, Vickers SA, Virnig BA, Tuttle TM. Lymph node evaluation is associated with improved survival after surgery for early stage gallbladder cancer. Surgery. 2009;146:706-711; discussion 711-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kayahara M, Nagakawa T, Ueno K, Ohta T, Takeda T, Miyazaki I. Lymphatic flow in carcinoma of the distal bile duct based on a clinicopathologic study. Cancer. 1993;72:2112-2117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Tsukada K, Kurosaki I, Uchida K, Shirai Y, Oohashi Y, Yokoyama N, Watanabe H, Hatakeyama K. Lymph node spread from carcinoma of the gallbladder. Cancer. 1997;80:661-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |