Published online Nov 14, 2019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i42.6365

Peer-review started: September 2, 2019

First decision: September 19, 2019

Revised: October 10, 2019

Accepted: October 18, 2019

Article in press: October 18, 2019

Published online: November 14, 2019

Processing time: 72 Days and 20.2 Hours

Epidemiologic studies have revealed a decrease in the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection in Western Europe.

To obtain data regarding the prevalence of H. pylori in Csongrád and Békés Counties in Hungary, evaluate the differences in its prevalence between urban and rural areas, and establish factors associated with positive seroprevalence.

One-thousand and one healthy blood donors [male/female: 501/500, mean age: 40 (19–65) years] were enrolled in this study. Subjects were tested for H. pylori IgG antibody positivity via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Subgroup analysis by age, gender, smoking habits, alcohol consumption, and urban vs non-urban residence was also performed.

The overall seropositivity of H. pylori was 32%. It was higher in males (34.93% vs 29.2%, P = 0.0521) and in rural areas (36.2% vs 27.94%, P = 0.0051). Agricultural/industrial workers were more likely to be positive for infection than office workers (38.35% vs 30.11%, P = 0.0095) and rural subjects in Békés County than those in Csongrád County (43.36% vs 33.33%, P = 0.0015).

Although the prevalence of H. pylori infection decreased in recent decades in Southeast Hungary, it remains high in middle-aged rural populations. Generally accepted risk factors for H. pylori positivity appeared to be valid for the studied population.

Core tip: Whereas a decrease in the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) has been confirmed in Western Europe, its prevalence in Central Europe, which has a substantial rural population, is unclear. Therefore, this study analyzed the prevalence of H. pylori among healthy volunteers in two Hungarian counties. The results of the study illustrated that the seropositivity of H. pylori in this area was 32%. The prevalence was higher in males, among people living in rural areas. Agricultural/industrial workers were more likely to be positive for infection than office workers. Meanwhile, rural subjects in Békés County had higher prevalence than those in Csongrád County.

- Citation: Bálint L, Tiszai A, Kozák G, Dóczi I, Szekeres V, Inczefi O, Ollé G, Helle K, Róka R, Rosztóczy A. Epidemiologic characteristics of Helicobacter pylori infection in southeast Hungary. World J Gastroenterol 2019; 25(42): 6365-6372

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v25/i42/6365.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i42.6365

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is one of the most common chronic human bacterial infections worldwide, affecting up to half of the world’s population. It is the main cause of gastritis, gastroduodenal ulcer, gastric adenocarcinoma, and mucosa-associated tissue lymphoma. Its prevalence is variable in relation to geography, ethnicity, age, and socioeconomic factors[1,2,3].

The prevalence of H. pylori has declined worldwide, although wide variation has been observed.

According to a 2017 and a 2018 meta-analysis, the countries with the lowest H. pylori prevalence were Switzerland (13.1%-24.7%), Denmark (17.8%-26.5%), New Zealand (21.4%-26.5%), Australia (17.2%-32.1%), and Sweden (18.3%-34.1%) in the former meta-analysis, Indonesia (10.0%), Belgium (11.0%), Ghana (14.2%), and Sweden (15.0) in the latter, whereas those with the highest prevalence were Nigeria (83.1%-92.2%), Portugal (84.9%-87.9%), Estonia (75.1%-90.0%), Kazakhstan (74.9%–84.2%), and Pakistan (75.6%-86.4%) in the former study, Serbia (88.3%), South Africa (86.8%), Nicaragua (83.3), and Colombia (83.1%) in the latter. The former study used two periods to analyze the prevalence trend over time. The H. pylori prevalence after 2000 was lower than that before 2000 in Europe (48.8 vs 39.8), North America (42.7% vs 26.6%), and Oceania (26.6% vs 18.7%)[4,5].

The major risk factors for H. pylori infection include socioeconomic status and the household hygiene of the patient and family during childhood. A previous Hungarian study revealed greater seropositivity among undereducated subjects, in persons living without sewers, those living in crowded homes or having three or more brothers and sisters, and those with high alcohol consumption, and they observed significant differences in prevalence between industrial and office workers. A Russian study reported that 88% of the Moscow working population is infected with H. pylori, 78% in people younger than 30 years, 97% in individuals older than 60 years. Recent epidemiologic studies revealed decreases in the prevalence of H. pylori in Western Europe and the United States. Conversely, little is known regarding the prevalence of H. pylori in Central Europe, in which a substantial population resides in rural areas[6,7,8,9,10].

The aims of this study were to obtain data regarding H. pylori prevalence in Csongrád and Békés Counties in Hungary, evaluate differences in prevalence between urban and rural areas, and establish factors associated with positive seroprevalence.

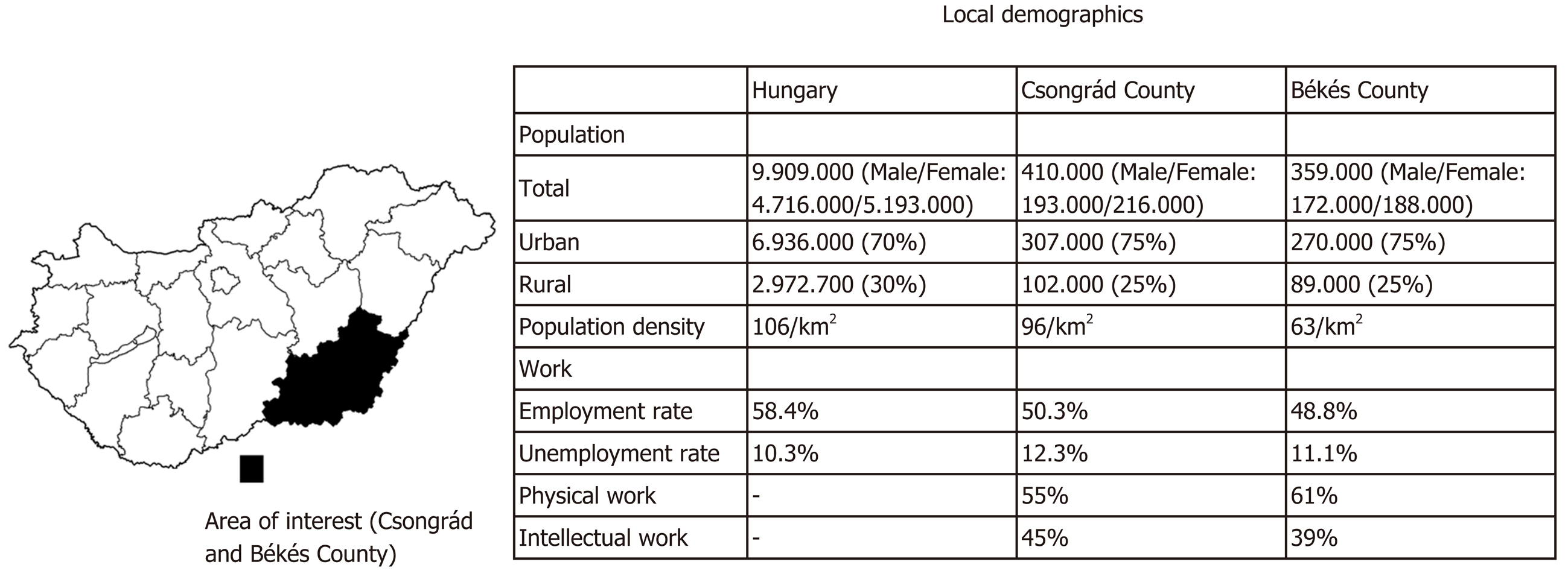

One-thousand and one healthy blood donors [male/female: 501/500, mean age: 40 (18–65) years] were consecutively enrolled in Csongrád and Békés Counties. Detailed demographic data are shown in Figure 1[11,12,13].

In Hungary, blood donation is allowed for individuals weighing more than 50 kg and aged 18–65 years. Data collection was performed using an anonymous questionnaire including 26 questions associated with demographic parameters (gender, age, place of birth, childhood residence, marital status, current residence, crowding in family, and educational status) and medical status (symptoms associated with H. pylori infection and gastroduodenal ulcer disease, smoking habits, alcohol consumption, and family history of H. pylori infection, gastroduodenal ulcer disease, and gastric malignancy).

On the basis of the childhood residence of the subjects, the following four groups of 250 subjects were established: Urban males, urban females, rural males, and rural females. Groups were matched by age. Subgroup analysis was performed according to living circumstances, residence in Békés or Csongrád County, smoking habits, alcohol and coffee consumption, occupation, intermittent agricultural work, pet or domestic animal rearing, gastrointestinal complaints, and family history of H. pylori infection, gastric ulcer, and gastric cancer.

All subjects were tested for H. pylori IgG antibody positivity using a Platelia H. pylori IgG enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, which reportedly has 100% sensitivity and 90% specificity according to the manufacturer. These values were 95.6% and 85.1% in the validation study of Burucoa et al[14] respectively (Bio-Rad).

For the statistical analysis of different variables related to H. pylori infection, the chi-squared test or two-sample t-test was applied. The association between H. pylori infection and potential risk factors was established via univariate analysis, and odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated. In addition, a stratified analysis according to age (18–35, 35–50, and 50–65 years) was performed. The final model was developed using a generalized linear regression model via stepwise regression, with inclusion and exclusion criteria set at significance levels of 0.05 and 0.10, respectively. A two-sided P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using MATLAB (Mathworks, Natwick, MA, United States).

The overall seropositivity of H. pylori was 32% in the studied healthy subjects. There was no statistically significant difference in prevalence between males and females (P = 0.0521) in our study. According to residence, the prevalence of H. pylori was significantly higher in rural areas than in urban areas (P = 0.0051). Furthermore, residence in rural areas for at least one year was associated with a significantly higher H. pylori prevalence than continuous urban residency (P = 0.0003). Parameters related to occupation were also associated with H. pylori infection. A higher prevalence was established for industrial workers and agricultural workers than for office workers and non-agricultural workers, respectively. Coffee consumption and pet or domesticated animal rearing were associated with H. pylori infection, whereas the rate of H. pylori positivity was similar for the remaining parameters. Detailed data are shown in Table 1-3.

| Socio-demographic factors | H. pylori positive | H. pylori negative | Total | P value | Odds ratio (univariate) | 95%CI | ||

| n | % | n | % | |||||

| Sex | 0.0521 | |||||||

| Female | 146 | 29.2 | 354 | 70.8 | 500 | 1.0 | ||

| Male | 175 | 34.9 | 326 | 65.1 | 501 | 1.3016 | [0.9973, 1.6987] | |

| Age | 0.000 | |||||||

| 44.5638 | 10.7693 | 37.3599 | 11.9457 | 0.9484 | [0.9363, 0.9606] | |||

| 18-25 | 25 | 14.9 | 143 | 85.1 | 168 | |||

| 25-35 | 32 | 16.9 | 157 | 83.1 | 189 | |||

| 35-45 | 97 | 34.4 | 185 | 65.6 | 282 | |||

| 45-55 | 106 | 43.6 | 137 | 56.4 | 243 | |||

| 55 + | 61 | 51.3 | 58 | 48.7 | 119 | |||

| Residence | 0.0809 | |||||||

| Urban | 185 | 30.0 | 431 | 70.0 | 616 | 1.0 | ||

| Rural | 136 | 35.3 | 249 | 64.7 | 385 | 1.2725 | [0.9706, 1.6683] | |

| Childhood | 0.0051 | |||||||

| Urban | 140 | 27.9 | 361 | 72.1 | 501 | 1.0 | ||

| Rural | 181 | 36.2 | 319 | 63.8 | 500 | 1.4631 | [1.1201, 1.9110] | |

| Min. one year in rural enviroment | 0.0003 | |||||||

| Negative | 104 | 25.6 | 303 | 74.4 | 407 | 1.0 | ||

| Positive | 217 | 36.5 | 377 | 63.5 | 594 | 1.6770 | [1.2695, 2.2153] | |

| Socio-economic + lifestyle factors | H. pylori positive | H. pylori negative | Total | P value | Odds ratio (univariate) | 95%CI | ||

| n | % | n | % | |||||

| Smoking | 0.1121 | |||||||

| Non-smoker | 169 | 29.5 | 403 | 70.5 | 572 | 1.0 | ||

| Smoker | 91 | 34.2 | 175 | 65.8 | 266 | 1.2400 | [0.9090, 1.6915] | |

| Former smoker | 61 | 37.4 | 102 | 62.6 | 163 | 1.4261 | [0.9904, 2.0534] | |

| Alcohol consumption | 0.1420 | |||||||

| Never | 95 | 36.0 | 169 | 64.0 | 264 | 1.0 | ||

| Occasional | 216 | 30.3 | 497 | 69.7 | 713 | 0.7731 | [0.5740, 1.0413] | |

| Regular | 10 | 41.7 | 14 | 58.3 | 24 | 1.2707 | [0.5434, 2.9715] | |

| Coffee | 0.0390 | |||||||

| Never | 82 | 26.7 | 225 | 73.3 | 307 | 1.0 | ||

| 1 | 94 | 36.3 | 165 | 63.7 | 259 | 1.5632 | [1.0929, 2.2358] | |

| More than 1 | 145 | 33.3 | 290 | 66.7 | 435 | 1.3720 | [0.9943, 1.8931] | |

| Household population | 0.1649 | |||||||

| Alone | 51 | 39.2 | 79 | 60.8 | 130 | 1.0 | ||

| Adults only | 135 | 31.5 | 294 | 68.5 | 429 | 0.7113 | [0.4736, 1.0683] | |

| Adults and children | 135 | 30.5 | 307 | 69.5 | 442 | 0.6812 | [0.4538, 1.0224] | |

| Work | 0.0000 | |||||||

| Industrial | 186 | 38.4 | 299 | 61.6 | 485 | 1.0 | ||

| Office | 135 | 26.2 | 381 | 73.8 | 516 | 0.5696 | [0.4355, 0.7450] | |

| Agricultural work | 0.0012 | |||||||

| No | 140 | 27.4 | 371 | 72.6 | 511 | 1.0 | ||

| Yes | 181 | 36.9 | 309 | 63.1 | 490 | 1.5523 | [1.1882, 2.0279] | |

| Domestic animals | 0.0015 | |||||||

| No | 54 | 23.5 | 176 | 76.5 | 230 | 1.0 | ||

| Yes | 267 | 34.6 | 504 | 65.4 | 771 | 1.7266 | [1.2301, 2.4236] | |

| Patient history | H. pylori positive | H. pylori negative | Total | P value | Odds ratio (univar-iate) | 95%CI | ||

| n | % | n | % | |||||

| Familiy history of H. pylori | 0.8829 | |||||||

| Negative | 161 | 32.5 | 335 | 67.5 | 496 | 1.0 | ||

| Positive | 18 | 31.0 | 40 | 69.0 | 58 | 0.9363 | [0.5205, 1.6844] | |

| NA | 142 | 31.8 | 305 | 68.2 | 447 | |||

| Family history of GI ulcer | 0.3810 | |||||||

| Negative | 217 | 33.3 | 435 | 66.7 | 652 | 1.0 | ||

| Positive | 57 | 29.7 | 135 | 70.3 | 192 | 0.8464 | [0.5965, 1.2009] | |

| NA | 47 | 29.9 | 110 | 70.1 | 157 | |||

| Family history of GI cancer | 0.0014 | |||||||

| Negative | 277 | 32.1 | 587 | 67.9 | 864 | 1.0 | ||

| Positive | 17 | 63.0 | 10 | 37.0 | 27 | 3.6025 | [1.6284, 7.9701] | |

| NA | 27 | 33.8 | 53 | 66.3 | 80 | |||

| Abdominal pain | 0.8108 | |||||||

| Negative | 264 | 32.2 | 555 | 67.8 | 819 | 1.0 | ||

| Positive | 57 | 31.3 | 125 | 68.7 | 182 | 0.9586 | [0.6784, 1.3547] | |

| Epigastrial pain | 0.1105 | |||||||

| Negative | 214 | 30.5 | 487 | 69.5 | 701 | 1.0 | ||

| Positive | 107 | 35.7 | 193 | 64.3 | 300 | 1.2617 | [0.9481, 1.6789] | |

A significant positive association was observed between age and H. pylori positivity (Table 1). To rule out this strong effect of age, three age groups were formed for further analysis. In the youngest group, the presence of epigastric pain was an independent risk factor for H. pylori positivity. By contrast, animal rearing was a risk factor for the middle age group, and male sex and living in rural areas for at least one year were risk factors in the oldest age group (Table 4).

| Age 18-35 | Age 35-50 | Age 50-65 | |

| Male sex | Not significant | Not significant | P = 0.0389; OR = 0.5847; CI: [0.0753 1.0940] |

| Rural residence in childhood | Not significant | Not significant | P = 0.0246; OR = 1.8537; CI: [1.3154 2.3920] |

| Animal rearing | Not significant | P = 0.0036; OR = 2.0855; CI: [1.5897 2.5812] | Not significant |

| Epigastrial pain complaint | P = 0.0026; OR = 2.5514; CI: [1.9422 3.1606] | Not significant | Not significant |

This prospective study proved that the Hungarian prevalence of H. pylori infection has followed international trends, falling to 32% over the last two decades. The prevalence between 1990 and 2000 was similar throughout the country (58.6%–63.3%) excluding the capital, in which the prevalence was only 47.3% (Table 5). Although the Southeastern region of the country was not studied prospectively before this study, the H. pylori Workgroup of our institute conducted a retrospective analysis in 2005 and 2010 among patients with dyspepsia and gastroduodenal ulcer disease. The rate of seropositivity decreased from 46% to 38%. The 2017 meta-analysis used two periods to analyze the changes of prevalence trend. The H. pylori prevalence after 2000 was lower than that before 2000 in Europe (48.8 vs 39.8), North America (42.7% vs 26.6%), and Oceania (26.6% vs 18.7%). In the surrounding Central European countries, such as the Czech Republic and Slovakia, the prevalence of H. pylori infection followed the trends of our region, decreasing from 42% to 23% after 10 years in the former from 62% to 35% after 15 years in the latter[4,6,15-21].

| Date | 1993 | 1999 | 2000 | 1998-2000 |

| Region | Tolna | Vas | Szabolcs-Szatmár-Bereg | Pest |

| Authors | Tamássy et al[15] | Lakner et al[6] | Iszlai et al[16] | Prónai et al[19] |

| Method | Serology | Serology | Serology | 13C-UBT |

| Population | Blood donors | Blood donors | Healthy volunteers | Symptomatic patients |

| n = | 400 | 533 | 756 | 1027 |

| Prevalence of H. pylori (%) | 63.3 | 62.3 | 58.6 | 47.3 |

Having examined the potential factors associated with a higher H. pylori prevalence, our results were in concordance with previous observations revealing a positive linear association with age. Furthermore, our study supported findings that rural subjects are more likely to be H. pylori-positive than urban residents. Although we could not establish a significant effect of gender on the seroprevalence, it is impressive that older rural males have an approximately sixfold higher risk of H. pylori positivity than young urban females (61.29% vs 11.11% P < 0.0001). Such results are most commonly explained by differences in socioeconomic status and household hygiene of the family during childhood. Furthermore, a new original finding is that people who lived in rural conditions for at least one year also had an increased risk for H. pylori seropositivity. An evaluation of the occupations of the subjects provided further proof that socioeconomic factors can influence H. pylori infection risk. Meanwhile, the lack of difference in risk between urban and rural residence can be explained by the general improvement of living standards in our country over the last two decades, as most rural people currently have access to water supply and sanitation[6-8,16,20-23].

The link between epigastric pain and H. pylori seropositivity among young subjects supports the currently accepted, Rome IV diagnostic protocol for functional dyspepsia, which states the excluding H. pylori infection (known as “H. pylori-associated dyspepsia”) should be the first step in the presence of such symptoms. Conversely, improved household hygiene in recent decades likely explains the lack of a relationship between socioeconomic status and H. pylori prevalence in this group. The findings further supported the hypothesis that hygiene differences between urban and rural areas were more significant at their childhood than nowadays. In addition, young males had poorer hygiene, than young females at that during childhood[24].

This study has a limitation. In Hungary, blood donors are unpaid, healthy, and conscious volunteers; therefore, they may not completely represent all segments of the population of Southeast Hungary.

In conclusion, we proved that in line with the worldwide trends, the prevalence of H. pylori infection has decreased in Southeast Hungary with changes of society, including improvements in socioeconomic status and living standards, during recent decades. Meanwhile, the prevalence remains high in the middle-aged and older rural populations. Generally accepted risk factors for H. pylori positivity appeared valid for the studied population, whereas the presence of dyspeptic symptoms was identified as an independent risk factor in the young population.

Epidemiologic studies have revealed a decrease in the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection in Western Europe. Conversely, little is known regarding its prevalence in Central Europe, in which a substantial population resides in rural areas.

The last Hungarian epidemiologic studies on H. pylori were carried out approximately two decades ago and showed high seroprevalence rates. Therfore we aimed to obtain new data and to test whether it decreases similarly to the Western European tendencies.

The aims of the present study were to obtain data regarding the prevalence of H. pylori in Csongrád and Békés Counties in Hungary, evaluate the differences in its prevalence between urban and rural areas, and establish factors associated with positive seroprevalence.

One-thousand and one healthy blood donors were enrolled. Data collection was performed using an anonymous questionnaire including 26 questions associated with demographic parameters and medical status. All subjects were tested for H. pylori IgG antibody positivity using IgG enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

The overall seropositivity of H. pylori was 32%. The prevalence of H. pylori was significantly higher in rural areas than in urban areas. Residence in rural areas for at least one year was associated with a significantly higher H. pylori prevalence than continuous urban residency. A significant positive association was observed between age, occupation, coffee consumption, pet or domesticated animal rearing and H. pylori positivity. Three age groups were formed for further analysis, in the youngest group, the presence of epigastric pain was an independent risk factor for H. pylori positivity.

The prevalence of H. pylori infection decreased in recent decades in Southeast Hungary, it remains high in middle-aged rural populations. Generally accepted risk factors for H. pylori positivity appeared to be valid for the studied population. Furthermore, a new original finding is that people who lived in rural conditions for at least one year also had an increased risk for H. pylori seropositivity.

The results of this study seems to consider the subsequent changes in seropositivity of H. pylori in Hungary. It would be interesting to test whether the significant positive association between age and H. pylori positivity continuous observed after 10 or 15 years or rather not, “new” infected will appear, or in the older age will stay low seropositivity. The other experience of this study is the link between epigastric pain and H. pylori seropositivity among young subjects, which supports the recommendation in countries with high H. pylori seropositivity, that patients with dyspeptic symptoms should be examined for H. pylori infection (Rome IV diagnostic protocol).

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Hungary

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Boyanova L, Mihara H, Reshetnyak VI, Triantafillidis JK S-Editor: Tang JZ L-Editor: A E-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Hunt RH, Xiao SD, Megraud F, Leon-Barua R, Bazzoli F, van der Merwe S, Vaz Coelho LG, Fock M, Fedail S, Cohen H, Malfertheiner P, Vakil N, Hamid S, Goh KL, Wong BC, Krabshuis J, Le Mair A; World Gastroenterology Organization. Helicobacter pylori in developing countries. World Gastroenterology Organisation Global Guideline. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2011;20:299-304. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Selgrad M, Bornschein J, Malfertheiner P. Helicobacter pylori: Infektion mit lokalen Komplikationen und systemischen Auswirkungen. Dtsch med Wochenschr. 2011;136:1790-1795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Fischbach W, Malfertheiner P, Hoffmann JC, Bolten W, Kist M, Koletzko S; Association of Scientific Medical Societies. Helicobacter pylori and gastroduodenal ulcer disease. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2009;106:801-808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hooi JKY, Lai WY, Ng WK, Suen MMY, Underwood FE, Tanyingoh D, Malfertheiner P, Graham DY, Wong VWS, Wu JCY, Chan FKL, Sung JJY, Kaplan GG, Ng SC. Global Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:420-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1361] [Cited by in RCA: 2046] [Article Influence: 255.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zamani M, Ebrahimtabar F, Zamani V, Miller WH, Alizadeh-Navaei R, Shokri-Shirvani J, Derakhshan MH. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the worldwide prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:868-876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 565] [Cited by in RCA: 491] [Article Influence: 70.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Lakner L, Jáger R, Toldy E, Sarang K, Varga L, Kovács LG, Döbrönte Z. A Helicobacter pylori infekció szeroepidemiológiai vizsgálata Vas megyében. Magy Belorv Arch. 1999;52:451-457. |

| 7. | Ford AC, Axon AT. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection and public health implications. Helicobacter. 2010;15:1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Goh KL, Chan WK, Shiota S, Yamaoka Y. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection and public health implications. Helicobacter. 2011;16:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 254] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Reshetnyak VI, Reshetnyak TM. Significance of dormant forms of Helicobacter pylori in ulcerogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:4867-4878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 10. | German SV, Zykova IE, Modestova AV, Ermakov NV. Epidemiological characteristics of Helicobacter pylori infection in Moscow. Gig Sanit. 2011;1:44-48. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Központi Statisztikai Hivatal, Hungarian Central Statistical Office. Magyarország számokban, 2014. Available from: https://www.ksh.hu/docs/hun/xftp/idoszaki/mosz/mosz13.pdf. |

| 12. | Központi Statisztikai Hivatal, Hungarian Central Statistical Office. Csongrád megye számokban, 2015. Available from: http://www.ksh.hu/docs/hun/xftp/idoszaki/regiok/mesz/06_cs_14.pdf. |

| 13. | Központi Statisztikai Hivatal, Hungarian Central Statistical Office. Békés megye számokban, 2014. Available from: http://www.ksh.hu/docs/hun/xftp/idoszaki/regiok/mesz/04_be.pdf. |

| 14. | Burucoa C, Delchier JC, Courillon-Mallet A, de Korwin JD, Mégraud F, Zerbib F, Raymond J, Fauchère JL. Comparative evaluation of 29 commercial Helicobacter pylori serological kits. Helicobacter. 2013;18:169-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Tamássy K, Simon L, Mégraud F. Helicobacter pylori infekció magyarországi epidemiológiája (szeroepidemiológiai összehasonlító tanulmány). Orvosi Hetilap. 1995;136:1387-1391. |

| 16. | Iszlai É, Kiss E, Toldy E, Ágoston S, Sipos B, Vén L, Rácz F, Szerafin L. Helicobacter pylori szeroprevalencia és anti-CagA pozitivitás Szabolcs-Szatmár-Bereg megyében. Orvosi Hetilap. 2003;144:1713-1718. |

| 17. | Bálint L, Tiszai A, Lénárt Z, Makhajda E, Wittmann T. Helicobacter pylori Infection and eradication therapy of our out patients in 2005 and 2010 years. What has been changed with time? Z Gastroenterol. 2011;49:638. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bálint L, Tiszai A, Dóczi I, Szekeres V, Makhajda E, Izbéki F, Róka R, Wittmann T, Rosztóczy A. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori (HP) infection in south hungarian healthy subjects. Z Gastroenterol. 2012;50:476. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Prónai L, Tulassay Zs. A Helicobacter pylori eradikációjának sikertelensége: szempontok a további kezelés megítéléséhez. Orvosi Hetilap. 2003;144:1299-1302. |

| 20. | Kuzela L, Oltman M, Sutka J, Zacharova B, Nagy M. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection in the Slovak Republic. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:754-756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bureš J, Kopáčová M, Koupil I, Seifert B, Skodová Fendrichová M, Spirková J, Voříšek V, Rejchrt S, Douda T, Král N, Tachecí I. Significant decrease in prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in the Czech Republic. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4412-4418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | de Martel C, Parsonnet J. Helicobacter pylori infection and gender: a meta-analysis of population-based prevalence surveys. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:2292-2301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Brown LM. Helicobacter pylori: epidemiology and routes of transmission. Epidemiol Rev. 2000;22:283-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 620] [Cited by in RCA: 625] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Stanghellini V, Chan FK, Hasler WL, Malagelada JR, Suzuki H, Tack J, Talley NJ. Gastroduodenal Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1380-1392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 818] [Cited by in RCA: 973] [Article Influence: 108.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |