Published online Jan 28, 2019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i4.485

Peer-review started: November 19, 2018

First decision: November 29, 2018

Revised: December 13, 2018

Accepted: January 9, 2019

Article in press: January 10, 2019

Published online: January 28, 2019

Processing time: 71 Days and 3.3 Hours

Endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) for the management of common bile duct stones (CBDS) is used increasingly widely because it is a minimally invasive procedure. However, some clinical practitioners argued that EST may be complicated by post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) pancreatitis (PEP) and accompanied by a higher recurrence of CBDS than open choledochotomy (OCT). Whether any differences in outcomes exist between these two approaches for treating CBDS has not been thoroughly elucidated to date.

To compare the outcomes of EST vs OCT for the management of CBDS and to clarify the risk factors associated with stone recurrence.

Patients who underwent EST or OCT for CBDS between January 2010 and December 2012 were enrolled in this retrospective study. Follow-up data were obtained through telephone or by searching the medical records. Statistical analysis was carried out for 302 patients who had a follow-up period of at least 5 years or had a recurrence. Propensity score matching (1:1) was performed to adjust for clinical differences. A logistic regression model was used to identify potential risk factors for recurrence, and a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was generated for qualifying independent risk factors.

In total, 302 patients undergoing successful EST (n = 168) or OCT (n = 134) were enrolled in the study and were followed for a median of 6.3 years. After propensity score matching, 176 patients remained, and all covariates were balanced. EST was associated with significantly shorter time to relieving biliary obstruction, anesthetic duration, procedure time, and hospital stay than OCT (P < 0.001). The number of complete stone clearance sessions increased significantly in the EST group (P = 0.009). The overall incidence of complications and mortality did not differ significantly between the two groups. Recurrent CBDS occurred in 18.8% (33/176) of the patients overall, but no difference was found between the EST (20.5%, 18/88) and OCT (17.0%, 15/88) groups. Factors associated with CBDS recurrence included common bile duct (CBD) diameter > 15 mm (OR = 2.72; 95%CI: 1.26-5.87; P = 0.011), multiple CBDS (OR = 5.09; 95%CI: 2.58-10.07; P < 0.001), and distal CBD angle ≤ 145° (OR = 2.92; 95%CI: 1.54-5.55; P = 0.001). The prediction model incorporating these factors demonstrated an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.81 (95%CI: 0.76-0.87).

EST is superior to OCT with regard to time to biliary obstruction relief, anesthetic duration, procedure time, and hospital stay and is not associated with an increased recurrence rate or mortality compared with OCT in the management of CBDS.

Core tip: Therapeutic outcomes of endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) and open choledochotomy (OCT) for the management of common bile duct stones (CBDS) have rarely been compared. The present study is the first to report on this issue and may represent the best evidence comparing these two interventions. The current results show that EST had more satisfactory short-term outcomes, including shorter time to biliary obstruction relief, anesthetic duration, procedure time, and hospital stay, than OCT. In addition, EST was not associated with a higher risk of subsequent recurrent CBDS or overall mortality.

- Citation: Zhou XD, Chen QF, Zhang YY, Yu MJ, Zhong C, Liu ZJ, Li GH, Zhou XJ, Hong JB, Chen YX. Outcomes of endoscopic sphincterotomy vs open choledochotomy for common bile duct stones. World J Gastroenterol 2019; 25(4): 485-497

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v25/i4/485.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i4.485

Common bile duct stones (CBDS), a common condition of the biliary tree, cause serious medical conditions, such as obstructive jaundice, gallstone pancreatitis, and severe acute cholangitis[1]. CBDS typically requires surgical intervention, which primarily involves open choledochotomy (OCT), endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST), and laparoscopic CBD exploration[2-4]. Many studies show that the classical approach of OCT has a wide range of adverse events, with a reported incidence ranging from 14% to 36% and a high mortality rate of 1% to 2%[5,6]. OCT also has long recovery time and can cause low gastrointestinal quality of life[7]. However, the latter two approaches (EST and laparoscopic CBD exploration) are increasingly used due to their low invasiveness. Accumulating evidence has confirmed the safety and efficacy of EST in the treatment of CBDS[8,9]. Unfortunately, EST has also been associated with many long-term sequelae, including recurrent CBDS, post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) pancreatitis (PEP), acute cholangitis (AC), and malignant degeneration, and thus requires further intervention[10,11]. Furthermore, the assessment of the relative advantages of these approaches is hindered by the fact that complications and mortality after OCT have declined with time. Therefore, the superiority of EST in general clinical terms does not mean that EST has more satisfactory treatment outcomes than OCT. To date, there is a lack of well-designed studies of robust data comparing the short- and long-term outcomes of EST with OCT in the treatment of CBDS. Additionally, the risk factors associated with recurrence have not been firmly established to date and thus are a focus of our study.

This study was approved by the institutional review board of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University. All patients gave written informed consent before the procedure. Inpatients undergoing successful EST or OCT between January 2010 and December 2012 for an initial diagnosis of CBDS with concomitant gallbladder stones or prior cholecystectomy were candidates for inclusion. The exclusion criteria were the presence of intrahepatic bile duct stones on computed tomography (CT) and/or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), previous EST, prior biliary surgery, biliary strictures, ampullary/pancreatic/biliary malignancies, hepatocirrhosis, severe cholangitis or active acute pancreatitis, and ≤ 18 years of age. Additionally, patients with gallbladder stones who did not undergo a cholecystectomy were also excluded from the study.

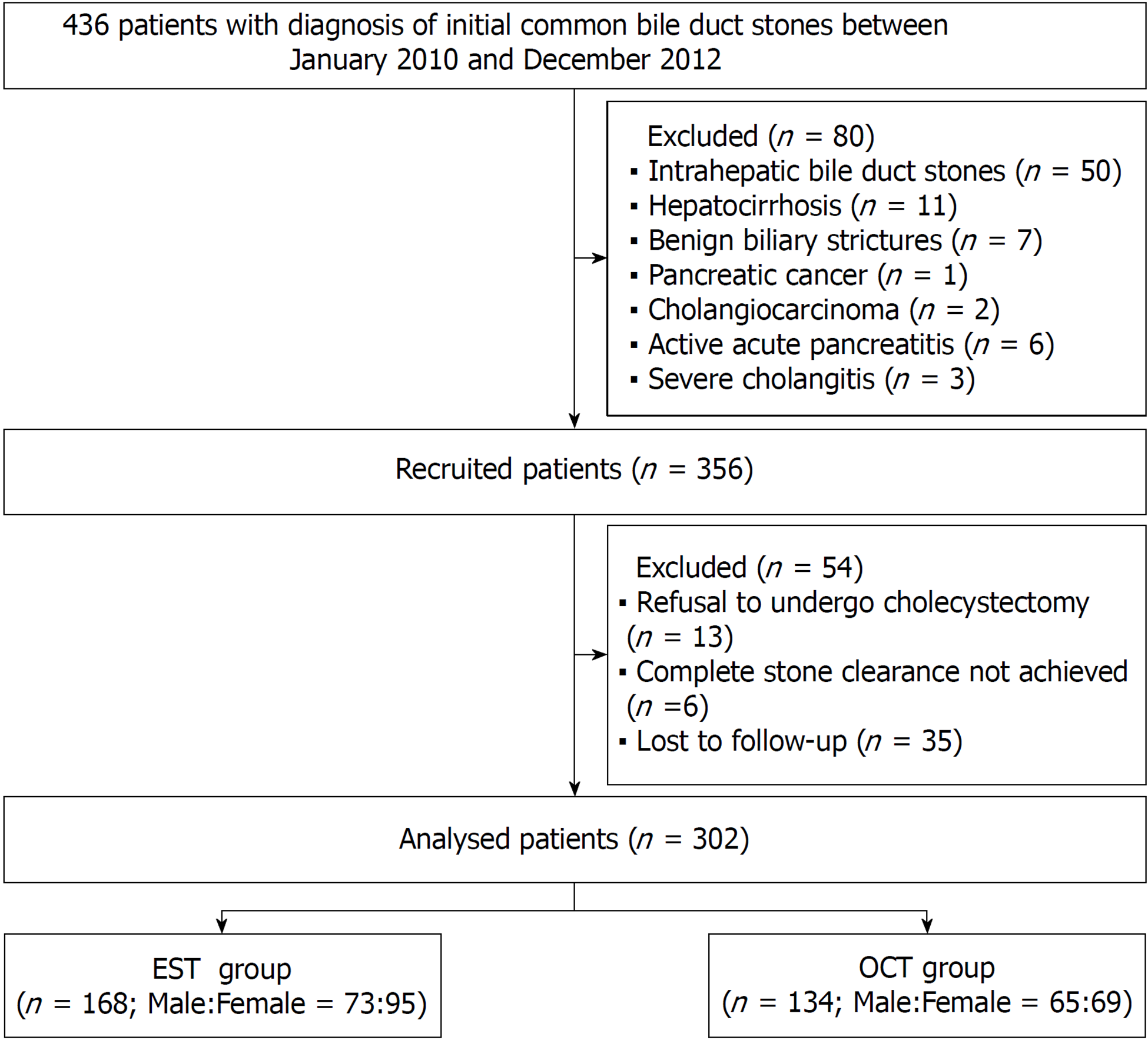

In total, 436 patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria were considered for the study. The following patients were excluded after confirmation by imaging and/or laboratory examinations: 50 patients with intrahepatic bile duct stones, 11 with hepatocirrhosis, 7 with benign biliary strictures, 3 with suspected malignancy, 6 with active acute pancreatitis, and 3 with severe cholangitis. Thus, 80 patients were excluded, and 356 patients were initially recruited. However, 13 patients with gallbladder stones refused to undergo a cholecystectomy, and in 6 patients, attempts to achieve complete stone clearance failed; additionally, 35 patients lost to follow-up were also excluded (Figure 1). Finally, 302 patients were enrolled for the analysis.

All procedures were performed by highly experienced (board-certified) endoscopists and general surgeons. Each patient’s medical records, including the chart, laboratory findings (complete blood count, coagulation function, and blood biochemistry), and imaging results (CT or MRCP), were reviewed to evaluate each patient’s general condition and to exclude contraindications prior to the procedure. All procedures were performed under intravenous sedation.

EST: EST was performed with a standard duodenoscope (TJF-240/TJF-260v; Olympus, Japan). Following deep cannulation with a sphincterotome, retrograde cholangiography, sphincterotomy, and CBDS extraction with either a basket or balloon were performed. Mechanical lithotripsy (ML) was used if necessary. A repeat cholangiogram was performed after stone removal to confirm complete clearance of the biliary tree. A temporary nasobiliary catheter was placed at the duct if gallbladder stones were present concurrently, and subsequent laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) was completed within several days post-ERCP.

OCT: OCT was achieved by open surgical exploration of the CBD. Stones were extracted by gently squeezing the CBD and/or by using a Dormia basket, followed by copious amounts of sodium chloride 0.9% for flushing to ensure patency. After ensuring CBD clearance with a choledochoscope, a T-tube was inserted into the CBD through the choledochotomy site, and a subhepatic drain was kept in all patients. The choledochotomy was closed using absorbable sutures followed by completion of the cholecystectomy and drain placement. T-tube cholangiography was performed 14-21 d postoperatively, and if no stone was discovered, the T-tube was clamped intermittently and removed after one month.

All patients were assessed daily after the intervention during their hospital stay. Outpatient visits were scheduled one month after the initial procedure and every three to six months thereafter. During outpatient follow-up, liver function tests and abdominal ultrasounds were reexamined if indicated clinically. All patients with recurrence of biliary symptoms were required to be readmitted to the hospital.

Follow-up data were collected by telephone or personal interview of the patients until December 2017 or until their death. All patients were asked about recurrence of biliary symptoms and reintervention methods if any were needed. Reintervention procedure data were also studied. If the patient died before our interview, the clinical history and cause of death were traced by interviewing the relatives.

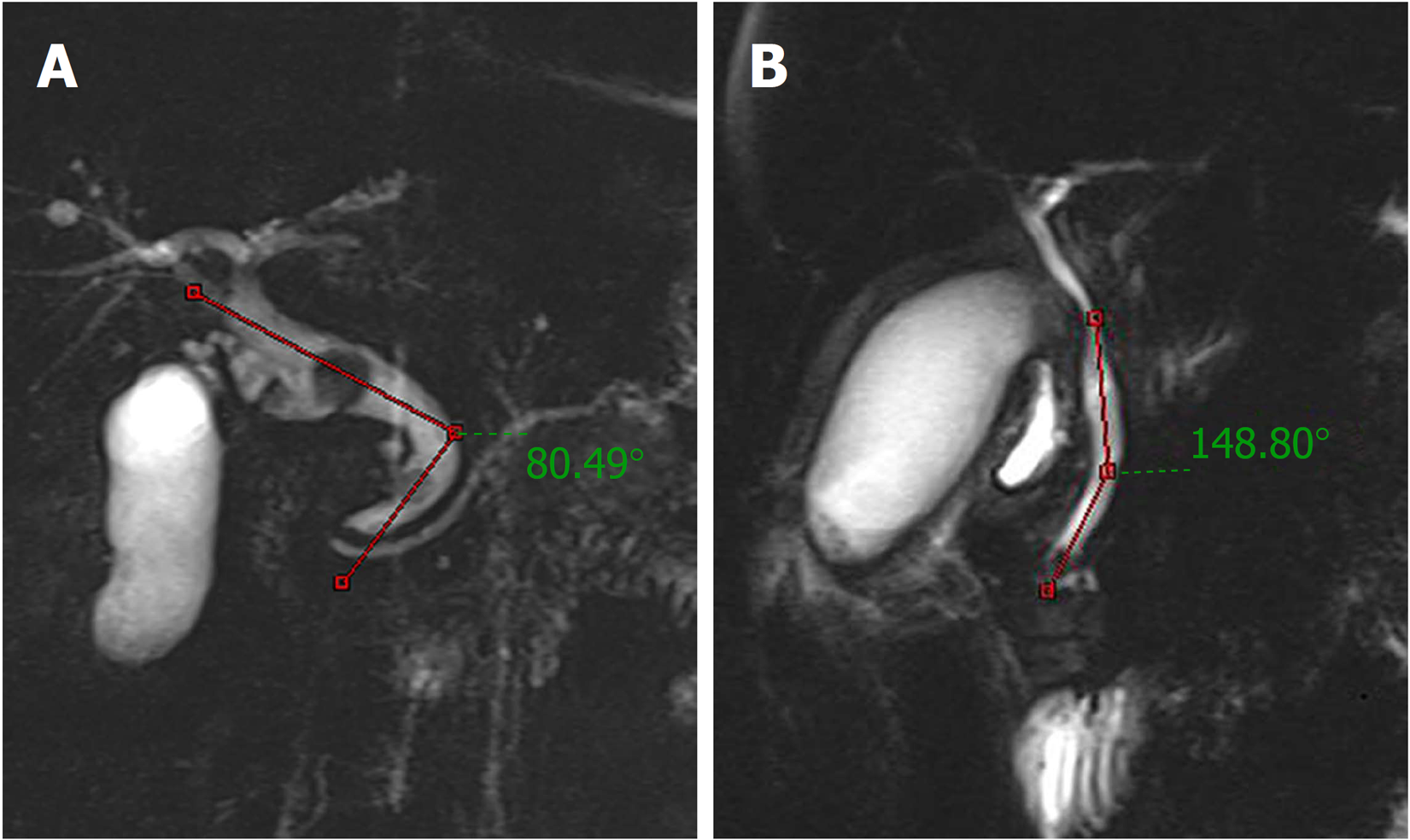

Recurrence of biliary symptoms was defined as the combination of fever/chills, jaundice, abdominal pain, abnormal liver function biochemical test results, and biliary dilatation and/or the existence of CBDS on imaging studies. Distal CBD angulation was defined as the first angulation from the ampullary orifice along the course of the CBD based on MRCP[12] (Figure 2). Acute cholangitis and its severity grading were defined according to the 2018 Tokyo Guidelines[13].

Short-term outcomes comprised time to biliary obstruction relief, procedure time, anesthetic duration, number of complete stone clearance sessions, complications, hospital stay, and hospitalization cost. Long-term outcomes were recurrent CBDS with or without AC, time to initial recurrence, times of recurrence, reintervention rate, reintervention method, and mortality.

Propensity score matching (1:1) was designed to limit the influences of confounding factors when estimating treatment outcomes between the two groups. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 19.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, United States). Continuous data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR). Groups were compared using Student’s t-test for variables with a normal distribution. For variables with skewed distribution, intergroup comparisons were made using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical data are displayed as n (%) and were analyzed with the Pearson chi-square test or the Fisher exact test as appropriate. Recurrence of CBDS was calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method with the use of the log-rank test. Variables with a P < 0.20 in the univariate analysis were introduced into a logistic regression model to analyze the findings of a multivariate analysis of CBDS recurrence. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was constructed to analyze the risk factors for CBDS recurrence and to determine the specific threshold value that would optimize its predictive value. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

In total, 302 patients were enrolled, and patient characteristics including baseline demographic data, clinical parameters, and follow-up outcomes are shown in Table 1. The information of these patients was gathered with a median follow-up period of 6.3 years (IQR: 5.4-7.3 years) and 6.2 years (IQR: 5.1-7.8 years) for the EST and OCT groups, respectively. There were 168 patients (73 males, 95 females; mean age, 57.1 ± 14.8 years) in the EST group and 134 patients (65 males, 69 females; mean age, 57.5 ± 13.5 years) in the OCT group. Cholecystectomy had been undertaken previously in 35 (11.6%) patients while 16 (5.3%) had undergone a prior gastrectomy (Billroth I: 7, Billroth II: 9). A gallbladder with stones in situ was observed in 267 patients (89.3% in the EST group vs 87.3% in the OCT group). The CBD diameter was significantly smaller in the EST group than in the OCT group (10.9 ± 4.4 mm vs 14.4 ± 5.8 mm, respectively; P < 0.001). Additionally, the maximum stone size varied between the EST and OCT groups, and this difference was statistically significant at a size ≥ 20 mm (P < 0.001). The two groups were similar in terms of the evaluated preoperative biochemical parameters aside from higher alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) concentrations in the EST group (P < 0.05).

| Characteristic | Before matching | After matching | |||||

| EST (n = 168) | OCT (n = 134) | P-value | EST (n = 88) | OCT (n = 88) | P-value | ||

| Age at enrollment, mean ± SD, yr | 57.1 ± 14.8 | 57.5 ± 13.5 | 0.799 | 58.6 ± 14.7 | 58.4 ± 13.8 | 0.920 | |

| Sex, male/female, n | 73/95 | 65/69 | 0.381 | 38/50 | 40/48 | 0.762 | |

| Bile duct diameter, mean ± SD, mm | 10.9 ± 4.4 | 14.4 ± 5.8 | < 0.001b | 12.4 ± 5.1 | 12.7 ± 4.2 | 0.663 | |

| Stone number, multiple/single, n | 63/105 | 57/77 | 0.374 | 33/55 | 33/55 | 1.000 | |

| Maximum stone size, n (%) | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 1.4 ± 0.7 | < 0.001b | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 0.484 | |

| Cholangitis on admission, n (%) | 42 (25.0) | 34 (25.4) | 0.941 | 23 (26.1) | 22 (25.0) | 0.863 | |

| Mild | 28 (16.6) | 28 (20.9) | 0.133 | 13 (14.7) | 18 (20.5) | 0.139 | |

| Moderate | 7 (4.2) | 5 (3.7) | 5 (5.7) | 3 (3.4) | |||

| Severe | 7 (4.2) | 1 (0.8) | 5 (5.7) | 1 (1.1) | |||

| Previous gastrectomy, n (%) | |||||||

| Billroth-I | 0 | 7 (5.2) | 0.006b | - | - | - | |

| Billroth-II | 0 | 9 (6.7) | 0.005b | - | - | - | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 19 (11.3) | 15 (11.2) | 0.951 | 12 (13.6) | 11 (12.5) | 0.823 | |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 11 (6.5) | 7 (5.2) | 0.629 | 7 (7.9) | 6 (6.8) | 0.773 | |

| Charlson comorbidity index, mean ± SD | 0.7 ± 0.9 | 0.8 ± 1.0 | 0.334 | 0.8 ± 1.0 | 0.8 ± 0.9 | 0.807 | |

| Prior cholecystectomy, n (%) | 18 (10.7) | 17 (12.7) | 0.595 | 12 (13.6) | 9 (10.2) | 0.485 | |

| Gallbladder with stones in situ, n (%) | 150 (89.3) | 117 (87.3) | 0.595 | 76 (86.4) | 79 (89.8) | 0.485 | |

| Preoperative biochemical parameters, median (IQR) | |||||||

| T-Bil, μmol/L | 18.9 (10.8-47.2) | 16.6 (9.5-39.1) | 0.164 | 16.9 (10.3-43.5) | 15.4 (9.1-40.3) | 0.432 | |

| ALT, U/L | 81.5 (28.8-162.0) | 40.5 (18.0-96.3) | < 0.001b | 56.0 (22.3-101.8) | 36.5 (17.5-98.3) | 0.264 | |

| AST, U/L | 47.0 (22.8-91.0) | 32.0 (20.0-62.2) | 0.053 | 37.0 (21.8-79.3) | 29.0 (19.0-60.0) | 0.259 | |

| γ-GTP, U/L | 162.5 (82.0-266.3) | 147.0 (67.5-264.8) | 0.446 | 131.5 (74.8-296.0) | 133.0 (64.8-226.8) | 0.380 | |

| ALP, U/L | 234.0 (76.0-475.5) | 126.5 (65.5-313.5) | 0.049a | 160.5 (66.3-351.5) | 121.0 (65.8-303.3) | 0.642 | |

| Follow up period, median (IQR), yr | 6.3 (5.4-7.3) | 6.2 (5.1-7.8) | 0.732 | 6.3 (5.2-7.3) | 6.9 (5.4-8.2) | 0.168 | |

Short-term outcomes: To adjust for differences in baseline clinical characteristics between the EST and OCT groups, propensity score matching (1:1) was performed and shown in Table 1. All clinical variables that can affect the outcomes were adjusted and compared after propensity score matching. Time from admission to biliary obstruction relief, median anesthetic duration, and procedure time were significantly shorter with EST than with OCT (P < 0.001). CBDS were completely cleared during the first procedure session in 77 patients in the EST group and in 86 patients in the OCT group, which was significantly different (P = 0.009). The median length of hospital stay was also shorter in the EST group than in the OCT group at 6.5 (IQR: 5-9.3) d vs 9 (IQR: 8-12) d, respectively (P < 0.001). However, there was no difference between groups for hospitalization cost. For procedure-related complications, a higher rate of bile leakage and port site infection was observed with OCT than with EST (2.3% vs 0% and 2.3% vs 0%, respectively). However, EST was associated with a significantly higher occurrence of PEP and hyperamylasemia than OCT (3.4% vs 0% and 4.5% vs 0%, respectively). However, the two groups did not differ, except for hyperamylasemia (P = 0.043) (Table 2).

| Short-term outcome measure | Before matching | After matching | |||||

| EST (n = 168) | OCT (n = 134) | P-value | EST (n = 88) | OCT (n = 88) | P-value | ||

| Time to biliary obstruction relief, mean ± SD, d | 2.8 ± 1.6 | 7.6 ± 4.3 | < 0.001b | 2.8 ± 1.6 | 7.1 ± 3.7 | < 0.001b | |

| Anesthetic duration, median (IQR), min | 174 (150-215) | 222 (181.8-269.8) | < 0.001b | 175 (149-217.8) | 207 (170-252.5) | < 0.001b | |

| 1Procedure time, median (IQR), min | 105 (84-141.2) | 150 (115.8-180) | < 0.001b | 110 (85-151.3) | 145 (112-180) | < 0.001b | |

| No. of complete stone clearance sessions, n (%) | < 0.032a | 0.009b | |||||

| 1 | 149 (88.7) | 128 (95.5) | 77 (87.5) | 86 (97.7) | |||

| ≥ 2 | 19 (11.3) | 26 (4.5) | 11 (12.5) | 22 (2.3) | |||

| Methods of cholecystectomy, n (%) | < 0.001b | < 0.001b | |||||

| OC | 7 (4.2) | 117 (87.3) | 1 (1.1) | 79 (89.8) | |||

| LC | 143 (85.1) | 0 | 75 (85.2) | 0 | |||

| 3Hospital stay, median (IQR), d | 6 (5-9) | 9 (8-12) | < 0.001b | 6.5 (5-9.3) | 9 (8-12) | < 0.001b | |

| Hospitalization cost, median (IQR), ×103 yuan | 17.9 (15.4-21.8) | 17.6 (13.7-21.2) | 0.083 | 18.0 (15.9-21.4) | 17.8 (14.3-21.5) | 0.115 | |

| Complications, n (%) | 19 (11.3) | 19 (14.2) | 0.455 | 9 (10.2) | 9 (10.2) | 1.000 | |

| Bleeding | 3 (1.8) | 7 (5.2) | 0.097 | 1 (1.1) | 4 (4.5) | 0.173 | |

| PEP | 6 (3.6) | 0 | 0.027a | 3 (3.4) | 0 | 0.081 | |

| Hyperamylasemia | 8 (4.8) | 0 | 0.010a | 4 (4.5) | 0 | 0.043a | |

| Cholangitis | 2 (1.2) | 1 (0.7) | 0.699 | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.1) | 1.000 | |

| Bile leakage | 0 | 5 (3.7) | 0.012a | 0 | 2 (2.3) | 0.155 | |

| Port site infection | 0 | 6 (4.8) | 0.006b | 0 | 2 (2.3) | 0.155 | |

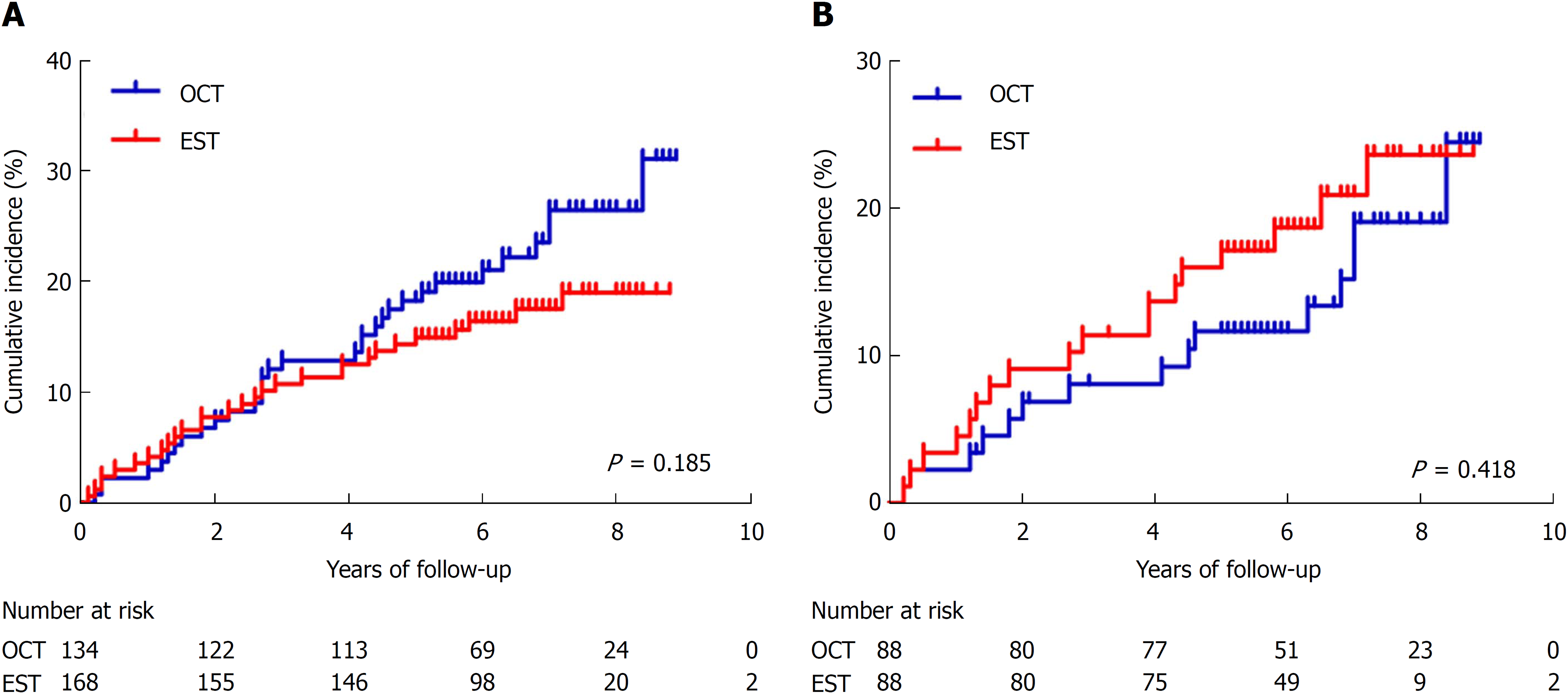

Long-term outcomes: The long-term follow-up results after propensity matching are summarized in Table 3. Recurrent CBDS occurred in a total of 33 (18.8%) patients. There was no significant difference in the recurrence rate between the EST (18/88, 20.5%) and OCT (15/88, 17.0%) groups (P = 0.418) (Figure 3). The rate of AC was significantly higher in the OCT group than in the EST group, but the difference did not reach significance (P = 0.054). The median time to initial recurrence was 3.0 ± 2.2 years in the EST group and 3.9 ± 2.7 in OCT group (P = 0.321). The number of patients with two or more recurrences was 3 (3.4%) and 4 (4.5%) in the EST and OCT groups, respectively (P = 0.700). Reinterventions were completed successfully in 15 of the EST patients and 14 of the OCT patients. Most of the patients in the EST group who had recurrence (14/15, 93.3%) elected to be treated again endoscopically. However, in the OCT group, a transition from OCT to EST was apparent (7/14, 50.0%), and only one patient underwent LCBDE (Table 3). Ten patients in the EST group and eight in the OCT group died from causes unrelated to biliary diseases (P = 0.995).

| Long-term outcome measure | Before matching | After matching | |||||

| EST (n = 168) | OCT (n = 134) | P-value | EST (n = 88) | OCT (n = 88) | P-value | ||

| Recurrent bile duct stones, n (%) | 29 (17.3) | 32 (23.9) | 0.155 | 18 (20.5) | 15 (17.0) | 0.562 | |

| With AC | 4 (2.4) | 12 (8.9) | 0.036a | 2 (2.4) | 6 (8.9) | 0.054 | |

| Without AC | 25 (14.9) | 20 (14.9) | 16 (14.9) | 9 (14.9) | |||

| Time to initial recurrence, mean ± SD, yr | 2.8 ± 2.0 | 3.5 ± 2.2 | 0.183 | 3.0 ± 2.2 | 3.9 ± 2.7 | 0.321 | |

| Times of recurrence ≥ 2, n (%) | 6 (3.6) | 11 (8.2) | 0.082 | 3 (3.4) | 4 (4.5) | 0.700 | |

| Reintervention rate, n (%) | 24 (14.3) | 29 (21.6) | 0.095 | 15 (17.0) | 14 (15.9) | 0.839 | |

| Reintervention method, n (%) | 0.002b | 0.032a | |||||

| EST | 23 (13.7) | 115 (11.2) | 14 (15.9) | 17 (7.9) | |||

| OCT | 1 (0.6) | 13 (9.7) | 1 (1.1) | 6 (6.8) | |||

| LCBDE | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 1 (1.1) | |||

| Mortality, n (%) | 14 (8.3) | 11 (8.2) | 0.969 | 10 (11.4) | 9 (10.2) | 0.808 | |

| Procedure-related | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | 0 | - | |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 0 | 2 (1.5) | 0.112 | 0 | 1 (1.1) | 0.316 | |

| Cardiopulmonary complication | 8 (4.8) | 4 (3.0) | 0.432 | 7 (7.9) | 4 (4.5) | 0.350 | |

| Unknown etiology | 6 (3.6) | 5 (3.7) | 0.941 | 3 (3.4) | 4 (4.5) | 0.700 | |

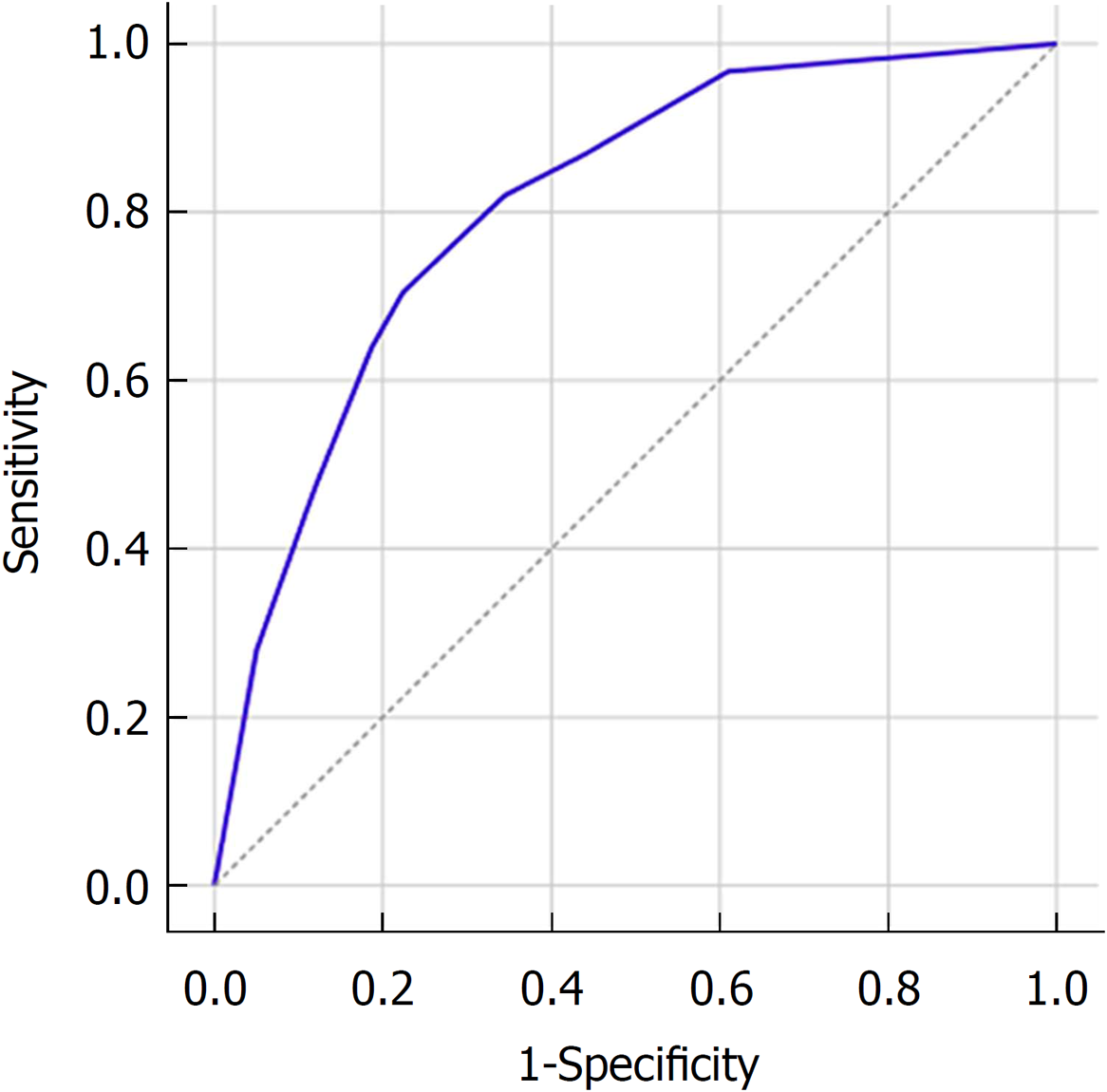

The results of logistic regression analysis are summarized in Table 4. Compared with OCT, EST was not associated with an increased rate of recurrent CBDS (OR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.47-1.86; P = 0.841). Notably, univariate analysis revealed that CBD diameter, maximum stone size, CBD stone number, and distal CBD angle ≤ 145° were associated with a significant increase in recurrence (P < 0.05). Multivariate analysis showed that CBD diameter ≥ 15 mm (OR = 2.72; 95%CI: 1.26-5.87; P = 0.011), multiple CBDS (OR = 5.09; 95%CI: 2.58-10.07; P < 0.001), and distal CBD angle ≤ 145° (OR = 2.92; 95%CI: 1.54-5.55; P = 0.001) were independent risk factors associated with CBDS recurrence. The presence of multiple stones seemed to be a much stronger risk factor. Multivariate models were built to predict the incidence of recurrence. According to the ROC of the multivariate model, the area under the curve (AUC) was 0.81 (95%CI: 0.76-0.87) (Figure 4). However, age, sex, ML, bacterial cholangitis, previous gastrectomy, and concomitant diseases were not found to be related to recurrence at the P > 0.05 level (Table 4).

| Variable | Recurrence, n (%) | P-value | Multivariate analysis | |||

| No (n = 241) | Yes (n = 61) | OR (95%CI) | P-value | |||

| Age, mean ± SD, yr | 57.2 ± 14.3 | 57.3 ± 14.1 | 0.974 | - | - | |

| Sex (female) | 131 (54.4) | 33 (54.1) | 0.971 | - | - | |

| Intervention method | 0.156 | 0.841 | ||||

| OCT | 102 (42.3) | 32 (52.5) | Reference | |||

| EST | 139 (57.7) | 29 (47.5) | 0.93 (0.47-1.86) | |||

| Bile duct diameter, cm | < 0.001b | 0.011b | ||||

| < 15 | 180 (74.7) | 25 (41.0) | Reference | |||

| ≥ 15 | 61 (25.3) | 36 (59.0) | 2.72 (1.26-5.87) | |||

| Distal CBD angle ≤ 145° | 78 (32.4) | 37 (60.6) | < 0.001b | 2.92 (1.54-5.55) | 0.001b | |

| Stone number | < 0.001b | < 0.001b | ||||

| Single | 167 (69.3) | 15 (24.6) | Reference | |||

| Multiple | 74 (30.7) | 46 (75.4) | 5.09 (2.58-10.07) | |||

| Maximum stone size, mm | 0.002b | 0.904 | ||||

| < 20 | 216 (89.6) | 45 (73.8) | Reference | |||

| ≥ 20 | 25 (10.4) | 16 (26.2) | 1.06 (0.43-2.63) | |||

| Mechanical lithotripsy | 9 (3.7) | 3 (4.9) | 0.673 | - | - | |

| Bacterial cholangitis | 63 (26.1) | 13 (21.3) | 0.438 | - | - | |

| Previous gastrectomy | ||||||

| Billroth-I | 6 (2.5) | 1 (1.6) | 0.696 | - | - | |

| Billroth-II | 6 (2.5) | 3 (4.9) | 0.328 | - | - | |

| Hypertension | 26 (10.8) | 8 (13.1) | 0.608 | - | - | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 17 (7.1) | 1 (1.6) | 0.145 | 0.29 (0.03-2.51) | 0.261 | |

| Charlson comorbidity index, mean ± SD | 0.7 ± 0.9 | 0.6 ± 0.9 | 0.499 | - | - | |

EST has been generally accepted as a primary treatment for CBDS in current practice and is especially popular for elderly and high-risk patients. Multiple long-term follow-up studies have validated the superiority of EST in terms of safety and efficacy[8,9]. Over the past decade, OCT has been used less frequently each year but is still been performed at a reasonable scale in many institutions. However, short- and long-term follow-up of patient outcomes for CBDS remains unevaluated in the current literature for either classical OCT or minimally invasive EST, which is a cause for concern, especially for younger patients. This study is the first to report on this issue and may represent the best evidence comparing these two interventions.

In this study, anesthetic duration and procedure time were obviously and significantly shorter in the EST group than in the OCT group. These benefits of EST may reduce the risk of anesthesia and the incidence of procedure-related complications, especially in the elderly with poor cardiopulmonary function. Bacterial infection secondary to prolonged partial or complete CBD obstruction may result in AC. This effect varies from mild disease that generally responds well to medical management alone to life-threatening disease with a mortality rate of approximately 5%-10% that requires urgent biliary decompression[14]. In our study, the mean time from admission to biliary obstruction relief was longer for OCT (7.1 ± 3.7 d) than for EST (2.8 ± 1.6 d; P < 0.001). Theoretically, EST can relieve obstruction faster and prevent the transition of cholangitis into severe acute cholangitis, which ultimately reduces the mortality of CBDS[15]. However, a previous retrospective study and a recent Cochrane review of 16 randomized studies demonstrated that EST did not reduce the morbidity and mortality rates of CBDS compared with surgical intervention[16,17]. This finding may have been due to a selection bias because most of the critical and elderly patients choose EST, as it is minimally invasive and relieves obstruction rapidly, whereas those with mild disease and generally better condition choose OCT as their preference. For example, numerous studies suggest that patients presenting with toxic cholangitis, severe gallstone pancreatitis, multiple comorbid conditions, or medical risk factors should be managed by urgent EST for endoscopic drainage. These patients are at an increased risk of mortality due to the severity of their illness rather than from the use of EST.

Failure with the initial attempt to treat CBDS results in multiple procedures, incurring a significant increase in health and financial burden. Theoretically, EST is easier to perform than OCT and, thus, would be expected to lower hospitalization cost. However, in the current study, total hospitalization cost was similar between the two groups, which probably resulted from the requirement for multiple procedure sessions in the EST group (12.5% vs 2.5%, P = 0.009).

The results of this study indicated that EST was equivalent to OCT in terms of efficacy for CBDS treatment, with both having similarly high technical success rates. However, with regards to safety, we found that the primary procedure-related complications of EST were bleeding, cholangitis, hyperamylasemia, and PEP, with incidence rates of 1.8%, 1.2%, 4.8%, and 3.6%, respectively. These findings concurred with previous studies[15,18]. PEP, as the most frequent complication of ERCP, was probably due to sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. This likely resulted from postprocedural edema or sphincter spasm, which may worsen compression of the pancreatic orifice and thus increase the risk of PEP. Additionally, EST itself and the use of pancreatic duct indwelling guidewires were also two independent risk factors for PEP. The primary factors influencing the efficiency and safety of EST appeared to be the skill and experience of the endoscopists, regardless of patient age or general medical condition. OCT followed by T-tube drainage is a safe and effective method for postoperative biliary decompression to maximize healing of the CBD incision. However, it is not exempt from complications, which occur in up to 10% of patients[19]. The most frequent of these are biliary leakage and port site infection after removal, which occurred in 3.7% and 4.8% of cases in the current study, respectively. Keeping the T-tube in place for an appropriate period of time decreases the incidence of bile leakage into the peritoneal cavity. Therefore, dislodgement or fracture of the T-tube or its premature removal may increase the risk of biliary leakage and port site infection.

Many scholars believe that endoscopic therapy shortens the length of hospital stay, but this advantage is offset by a substantially higher rate of recurrent biliary symptoms, some of which demand readmission. Conversely, our results indicated that the OCT group had a higher rate of CBDS recurrence than the EST group, although this difference was not statistically significant (20.5% vs 17.0%, P = 0.418). Presently, there are no relevant studies confirming our findings. Additionally, patients with recurrent CBDS complicated by AC were observed significantly more frequently after OCT, but there was no significant difference when compared with EST (P = 0.054). It is possible that hyperplasia of fibrous scar tissue at the CBD incision site after OCT could cause CBD angulation or malformation. This effect may lead to chronic inflammation and thus cholangitic stenosis of the CBD, contributing to biliary tract bacterial infection by disturbing bile excretion and ultimately resulting in AC. With EST, there has been concern expressed that duodenobiliary reflux due to permanent loss of sphincter of Oddi function may lead to recurrence of stones or ascending cholangitis[20,21].

In the current study, we found a significant association between the two groups in terms of the length of time to initial recurrence of CBDS. Accumulating studies have reported that most recurrences occurred within the first 2 years after EST[22]. Similarly, 39.3% of recurrences in our study occurred within 2 years of EST. These studies found that sphincter of Oddi basal pressure and amplitude decreased markedly after EST but could recover to some extent 2 years following this procedure[23]. However, except for inflammatory stenosis, no studies have fully explained the underlying pathogenesis of stone recurrence after OCT. Thus, further study on this topic is needed.

Christos et al[24] proposed that patients with recurrent CBDS were at an increased risk of a subsequent recurrence. In our study, 21.2% of patients with one recurrence had at least one further episode, while the first-time recurrence rate was 18.8%. However, there was no significant difference in the rates of a second recurrence between the EST and OCT groups in our study (P = 0.700). Furthermore, the rates of reintervention for an initial recurrence were similar in the EST and OCT groups (17.0% vs 15.9%, P = 0.839). However, EST was the approach chosen more frequently for reintervention for recurrent patients, with over 50.0% (7/14) of patients transferring from the OCT group to EST therapy. This could be due to EST being more favorable for postoperative recovery, with decreased pain and an increase in quality of life in the short term. Moreover, free external drainage from T-tubes may lead to slow wound healing, anorexia, and constipation, as well as increasing the risk of dehydration and electrolyte imbalance[25]. Mortality was very low, and there was no significant difference in the postprocedure death rate between the two groups in our study. Our results concur with that of a retrospective study in which 1514 patients with CBDS were treated by OCT and the operative mortality was 2%. During our follow-up, we found that the primary causes of death were cardiopulmonary complications and unknown etiology rather than procedure-related adverse events.

The recurrence rate for CBDS quoted in the literature ranges from 4%-25%[11]. However, the risk factors for stone recurrence remain unknown. Numerous studies have found that bile stagnation, duodenal-biliary reflux, bacterial colonization of the CBD, ML, and CBD angulation or deformity all contribute to recurrence[26]. However, our study demonstrated that ML and CBD bacterial infection did not increase recurrence incidence. Although univariate analysis revealed that the stone recurrence rate was higher in patients with stones ≥ 20 mm, this was not statistically significant in multivariate analysis. Multivariate analysis revealed that CBD diameter, CBD angle ≤ 145°, and multiple CBDS were independent risk factors for CBDS recurrence. The underlying mechanism for CBD dilation, which predisposes to stone reformation, may be a decrease or loss of normal CBD functional movement or a decrease in the hydrostatic force of bile. Both of these events could slow down bile excretion, thus leading to CBDS formation. Additionally, cholesterol in the bile of patients with multiple stones might be prone to crystallizing and nucleating, causing a tendency toward stone formation.

The comprehensive and long-term follow-up in our study provides novel insights into the different outcomes with EST and OCT, and the risk factors for subsequent stone recurrence. However, there are several limitations to our study. First, we could not rule out the possibility that recurrent CBDS might be asymptomatic and evade detection during follow-up. Second, due to its retrospective nature, a selection bias may have occurred with the two treatment groups. Last, we did not ascertain the composition of the stones at the initial intervention. Therefore, we could not examine whether differences in stone composition affected the risk of recurrent CBDS.

In conclusion, EST currently remains the most commonly performed procedure for CBDS management. This may be because it is minimally invasive and has satisfactory short-term outcomes including shorter time to biliary obstruction relief, anesthetic duration, procedure time, and hospital stay. Furthermore, EST can be performed safely without posing a higher risk of subsequent recurrent CBDS or overall mortality than OCT. The recurrence rate appears to be associated with CBD diameter ≥ 15 mm, multiple CBDS, and distal CBD angle ≤ 145°.

Endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) and open choledochotomy (OCT) are two common therapeutic modalities for the management of common bile duct stones (CBDS). Over time, EST as a minimally invasive approach has become safe, efficient, and cost-effective. However, it remains unclear whether there are any differences in outcomes between these two approaches for the treatment of CBDS.

Some clinical practitioners argued that EST may be complicated by post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) pancreatitis (PEP) and are associated with a higher recurrence of CBDS than OCT. Additionally, the risk factors associated with recurrence have not yet been established firmly. We wanted to investigate these issues to help guide clinicians in efforts to manage CBDS better.

The retrospective study aimed to compare the clinical outcomes of EST vs OCT for the management of CBDS and to identify the risk factors associated with stone recurrence.

This study included 302 patients with CBDS who met the criteria. The short- and long-term clinical outcomes were compared between the EST and OCT groups. Propensity score matching was performed to adjust for the effects of confounding factors. Recurrence of CBDS was calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method with the use of the log-rank test. Risk factors for recurrence were identified using a logistic regression model.

EST was associated with shorter time to relieving the biliary obstruction, anesthetic duration, procedure time, and hospital stay than OCT. The overall incidence of complications and mortality did not differ significantly between the two groups. There was no significant difference in recurrence rate between the EST (18/88, 20.5%) and OCT (15/88, 17.0%) groups. The area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for the logistic regression model incorporating CBD diameter ≥ 15 mm, multiple CBDS, and distal CBD angle ≤ 145° was 0.81 (95%CI: 0.76-0.87).

EST shows better results in short-term outcomes, including shorter time to relief of biliary obstruction, anesthetic duration, procedure time, and hospital stay, and was not associated with an increased recurrence rate or mortality compared with OCT in the management of CBDS. CBD dilatation, multiple CBDS, and distal CBD angle ≤ 145° are independent risk factors for CBDS recurrence, and these factors may help screen out high-risk patients who require follow-up more frequently.

EST can be performed safely without posing a higher risk of subsequent recurrent CBDS or overall mortality than OCT. Additional randomized controlled trials are needed to further validate these findings.

We are grateful to all the participants and colleagues for their contribution.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

P- Reviewer: Kitamura K, Kozarek RA, Sugimoto M S- Editor: Ma RY L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Yin SY

| 1. | Stinton LM, Shaffer EA. Epidemiology of gallbladder disease: cholelithiasis and cancer. Gut Liver. 2012;6:172-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 556] [Cited by in RCA: 737] [Article Influence: 56.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Pitt HA. Role of open choledochotomy in the treatment of choledocholithiasis. Am J Surg. 1993;165:483-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hanif F, Ahmed Z, Samie MA, Nassar AH. Laparoscopic transcystic bile duct exploration: the treatment of first choice for common bile duct stones. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1552-1556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kageoka M, Watanabe F, Maruyama Y, Nagata K, Ohata A, Noda Y, Miwa I, Ikeya K. Long-term prognosis of patients after endoscopic sphincterotomy for choledocholithiasis. Dig Endosc. 2009;21:170-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zhu QD, Tao CL, Zhou MT, Yu ZP, Shi HQ, Zhang QY. Primary closure versus T-tube drainage after common bile duct exploration for choledocholithiasis. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2011;396:53-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tham TC, Carr-Locke DL, Collins JS. Endoscopic sphincterotomy in the young patient: is there cause for concern? Gut. 1997;40:697-700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Liu F, Bai X, Duan GF, Tian WH, Li ZS, Song B. Comparative quality of life study between endoscopic sphincterotomy and surgical choledochotomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:8237-8243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sugiyama M, Atomi Y. Follow-up of more than 10 years after endoscopic sphincterotomy for choledocholithiasis in young patients. Br J Surg. 1998;85:917-921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Costamagna G, Tringali A, Shah SK, Mutignani M, Zuccalà G, Perri V. Long-term follow-up of patients after endoscopic sphincterotomy for choledocholithiasis, and risk factors for recurrence. Endoscopy. 2002;34:273-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, Moore JP, Fennerty MB, Ryan ME, Shaw MJ, Lande JD, Pheley AM. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1716] [Cited by in RCA: 1689] [Article Influence: 58.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 11. | Prat F, Malak NA, Pelletier G, Buffet C, Fritsch J, Choury AD, Altman C, Liguory C, Etienne JP. Biliary symptoms and complications more than 8 years after endoscopic sphincterotomy for choledocholithiasis. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:894-899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kim HJ, Choi HS, Park JH, Park DI, Cho YK, Sohn CI, Jeon WK, Kim BI, Choi SH. Factors influencing the technical difficulty of endoscopic clearance of bile duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:1154-1160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kiriyama S, Kozaka K, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Pitt HA, Gabata T, Hata J, Liau KH, Miura F, Horiguchi A, Liu KH, Su CH, Wada K, Jagannath P, Itoi T, Gouma DJ, Mori Y, Mukai S, Giménez ME, Huang WS, Kim MH, Okamoto K, Belli G, Dervenis C, Chan ACW, Lau WY, Endo I, Gomi H, Yoshida M, Mayumi T, Baron TH, de Santibañes E, Teoh AYB, Hwang TL, Ker CG, Chen MF, Han HS, Yoon YS, Choi IS, Yoon DS, Higuchi R, Kitano S, Inomata M, Deziel DJ, Jonas E, Hirata K, Sumiyama Y, Inui K, Yamamoto M. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: diagnostic criteria and severity grading of acute cholangitis (with videos). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018;25:17-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 468] [Cited by in RCA: 424] [Article Influence: 60.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lai EC, Mok FP, Tan ES, Lo CM, Fan ST, You KT, Wong J. Endoscopic biliary drainage for severe acute cholangitis. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1582-1586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 410] [Cited by in RCA: 328] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mallery JS, Baron TH, Dominitz JA, Goldstein JL, Hirota WK, Jacobson, BC, Leighton JA, Raddawi HM, Varg JJ 2nd, Waring JP, Fanelli RD, Wheeler-Harbough J, Eisen GM, Faigel DO; Standards of Practice Committee. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Complications of ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:633-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Miller BM, Kozarek RA, Ryan JA, Ball TJ, Traverso LW. Surgical versus endoscopic management of common bile duct stones. Ann Surg. 1988;207:135-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Dasari BV, Tan CJ, Gurusamy KS, Martin DJ, Kirk G, McKie L, Diamond T, Taylor MA. Surgical versus endoscopic treatment of bile duct stones. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;CD003327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Elmunzer BJ, Scheiman JM, Lehman GA, Chak A, Mosler P, Higgins PD, Hayward RA, Romagnuolo J, Elta GH, Sherman S, Waljee AK, Repaka A, Atkinson MR, Cote GA, Kwon RS, McHenry L, Piraka CR, Wamsteker EJ, Watkins JL, Korsnes SJ, Schmidt SE, Turner SM, Nicholson S, Fogel EL; U. S. Cooperative for Outcomes Research in Endoscopy (USCORE). A randomized trial of rectal indomethacin to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1414-1422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 478] [Cited by in RCA: 503] [Article Influence: 38.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Pérez G, Escalona A, Jarufe N, Ibáñez L, Viviani P, García C, Benavides C, Salvadó J. Prospective randomized study of T-tube versus biliary stent for common bile duct decompression after open choledocotomy. World J Surg. 2005;29:869-872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Cheon YK, Lee TY, Kim SN, Shim CS. Impact of endoscopic papillary large-balloon dilation on sphincter of Oddi function: a prospective randomized study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:782-790.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zhang R, Luo H, Pan Y, Zhao L, Dong J, Liu Z, Wang X, Tao Q, Lu G, Guo X. Rate of duodenal-biliary reflux increases in patients with recurrent common bile duct stones: evidence from barium meal examination. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:660-665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Jacobsen O, Matzen P. Long-term follow-up study of patients after endoscopic sphincterotomy for choledocholithiasis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1987;22:903-906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Gregg JA, Carr-Locke DL. Endoscopic pancreatic and biliary manometry in pancreatic, biliary, and papillary disease, and after endoscopic sphincterotomy and surgical sphincteroplasty. Gut. 1984;25:1247-1254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sugiyama M, Suzuki Y, Abe N, Masaki T, Mori T, Atomi Y. Endoscopic retreatment of recurrent choledocholithiasis after sphincterotomy. Gut. 2004;53:1856-1859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ambreen M, Shaikh AR, Jamal A, Qureshi JN, Dalwani AG, Memon MM. Primary closure versus T-tube drainage after open choledochotomy. Asian J Surg. 2009;32:21-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Konstantakis C, Triantos C, Theopistos V, Theocharis G, Maroulis I, Diamantopoulou G, Thomopoulos K. Recurrence of choledocholithiasis following endoscopic bile duct clearance: Long term results and factors associated with recurrent bile duct stones. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;9:26-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |