Published online Sep 21, 2019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i35.5344

Peer-review started: July 15, 2019

First decision: August 18, 2019

Revised: August 28, 2019

Accepted: September 9, 2019

Article in press: September 9, 2019

Published online: September 21, 2019

Processing time: 70 Days and 16.8 Hours

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) has been routinely performed in applicable early gastric cancer (EGC) patients as an alternative to conventional surgical operations that involve lymph node dissection. The indications for ESD have been recently expanded to include larger, ulcerated, and undifferentiated mucosal lesions, and differentiated lesions with slight submucosal invasion. The risk of lymph node metastasis (LNM) is the most important consideration when deciding on a treatment strategy for EGC. Despite the advantages over surgical procedures, lymph nodes cannot be removed by ESD. In addition, whether patients who meet the expanded indications for ESD can be managed safely remains controversial.

To determine whether the ESD indications are applicable to Chinese patients and to investigate the predictors of LNM in EGC.

We retrospectively analyzed 12552 patients who underwent surgery for gastric cancer between June 2007 and December 2018 at the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University. A total of 1262 (10.1%) EGC patients were eligible for inclusion in this study. Data on the patients’ clinical, endoscopic, and histopathological characteristics were collected. The absolute and expanded indications for ESD were validated by regrouping the enrolled patients and determining the positive LNM results in each subgroup. Predictors of LNM in patients were evaluated by univariate and multivariate analyses.

LNM was observed in 182 (14.4%) patients. No LNM was detected in the patients who met the absolute indications (0/90). LNM occurred in 4/311 (1.3%) patients who met the expanded indications. According to univariate analysis, LNM was significantly associated with positive tumor marker status, medium (20-30 mm) and large (>30 mm) lesion sizes, excavated macroscopic-type tumors, ulcer presence, submucosal invasion (SM1 and SM2), poor differentiation, lymphovascular invasion (LVI), perineural invasion, and diffuse and mixed Lauren’s types. Multivariate analysis demonstrated SM1 invasion (odds ration [OR] = 2.285, P = 0.03), SM2 invasion (OR = 3.230, P < 0.001), LVI (OR = 15.702, P < 0.001), mucinous adenocarcinoma (OR = 2.823, P = 0.015), and large lesion size (OR = 1.900, P = 0.006) to be independent risk factors.

The absolute indications for ESD are reasonable, and the feasibility of expanding the indications for ESD requires further investigation. The predictors of LNM include invasion depth, LVI, mucinous adenocarcinoma, and lesion size.

Core tip: We aimed to re-evaluate and verify the current indications and guidelines for endoscopic treatment and to analyze the clinicopathological predictors of lymph node metastasis in early gastric cancer (EGC), which have been inconsistently identified across studies. To the best of our knowledge, this study involves the largest number of EGC patients in China, and is the first study to perform statistical analyses on certain clinical features, such as drinking, smoking, obesity, family history of tumors, and tumor markers.

- Citation: Chu YN, Yu YN, Jing X, Mao T, Chen YQ, Zhou XB, Song W, Zhao XZ, Tian ZB. Feasibility of endoscopic treatment and predictors of lymph node metastasis in early gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2019; 25(35): 5344-5355

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v25/i35/5344.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i35.5344

Gastric cancer is currently the fifth most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide[1]. Early gastric cancer (EGC) is defined as a tumor that is confined to the mucosa and submucosa of the stomach, irrespective of regional lymph node metastasis (LNM)[2]. Several studies have reported a frequency of LNM ranging from 5%-10% among EGC patients undergoing radical surgery[3], suggesting that over 90% of surgeries could potentially be avoided if curative endoscopic resection (ER) is accurately predicted based on the histopathology of an endoscopic-resected specimen.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) has notable advantages over conventional surgical resection, as it causes less trauma, minor bleeding, and fewer postoperative complications[4]. The absolute indications for ESD for curative resection in EGC that were proposed by the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association (JGCA) initially include nonulcerated, well-differentiated mucosal lesions ≤ 2 cm in diameter[5]. The absolute indications for ESD, however, are so strict that unnecessary surgeries may be performed. Subsequently, the expanded indications for ESD, which include larger, ulcerated, and undifferentiated mucosal lesions as well as differentiated lesions with slight submucosal invasion, were proposed. A recent meta-analysis involving 12 studies revealed that the incidence of LNM was only 0.2% among patients who met the absolute indications, compared with an LNM incidence of 0.7% among patients who met the expanded indications[6]. Furthermore, several studies have shown that LNM is closely related to an unsatisfactory prognosis in EGC[7-10].

To date, universal preoperative examination methods, such as gastroscopy, endoscopic ultrasonography, computed tomography, and X rays, fail to provide adequate data on the lesion and regional lymph node status before surgery or ER[11]. However, evaluating the risk of LNM is critical for determining the best course of management for EGC patients[12]. Unfortunately, the risk factors that have been identified in different studies are diverse, and controversy still exists regarding the expanded indications for ESD. Therefore, in this study, which involved a relatively large number of EGC patients, we aimed to reevaluate and verify the current guidelines for endoscopic treatment of EGC in a Chinese population and to investigate the predictors of EGC with LNM.

We retrospectively reviewed all patients who were diagnosed with gastric cancer and underwent gastrectomy with lymphadenectomy between June 2007 and December 2018 at the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University. This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2000) of the World Medical Association. Our study was also approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University (QYFY WZLL 2019-04-04). In all, 12552 patients were reviewed. Patients were excluded if they had: (1) Advanced-stage gastric cancer (n = 11099); (2) Intestinal metaplasia or intraepithelial neoplasia (n = 72); (3) Metastatic gastric cancer or multiple carcinomas (n = 38); (4) Lymphoma (n = 28); (5) Gastric stump carcinoma (n = 36); and (6) Other life-threatening diseases (n = 17). Ultimately, 1262 EGC patients were enrolled in this study.

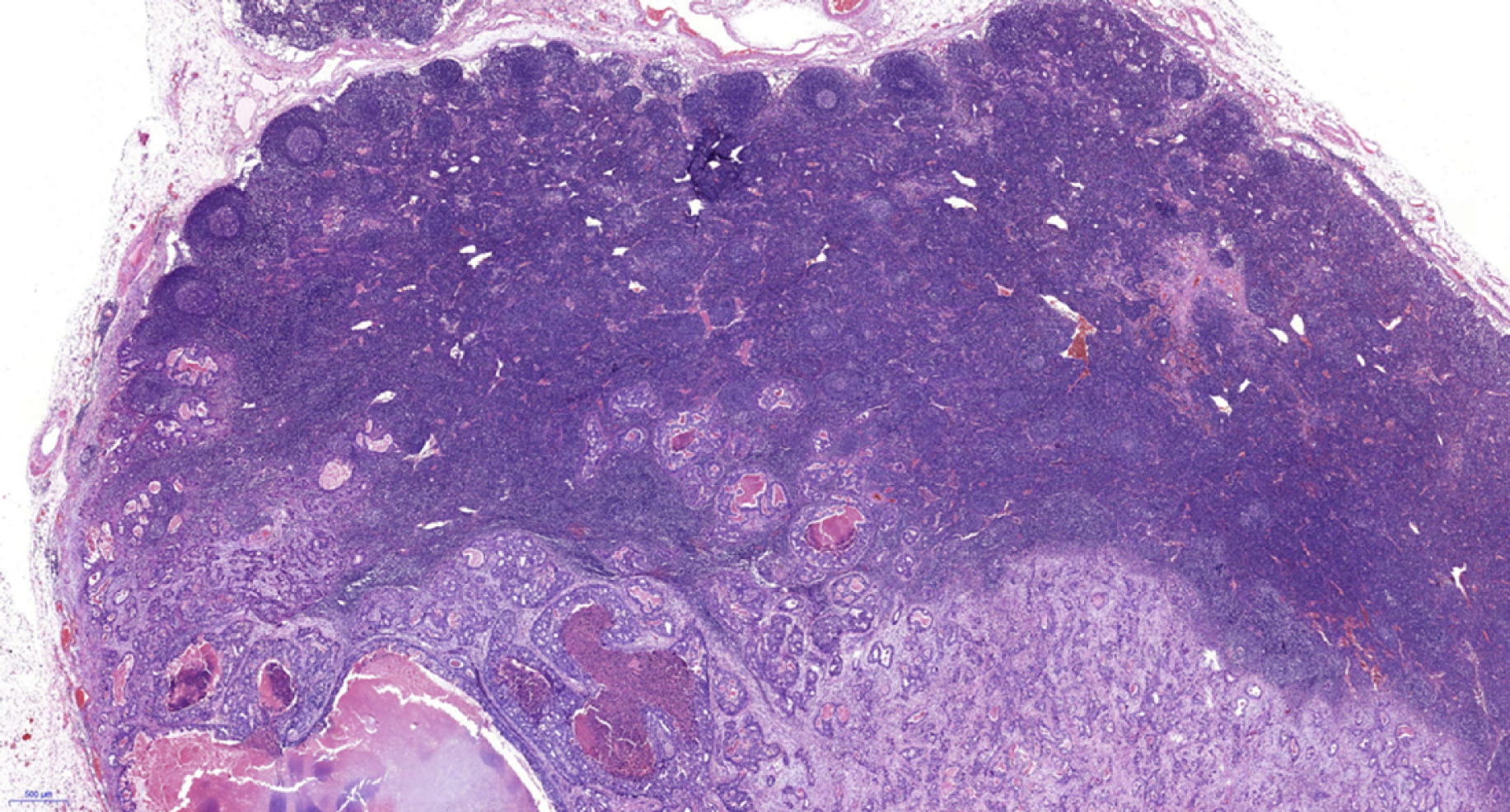

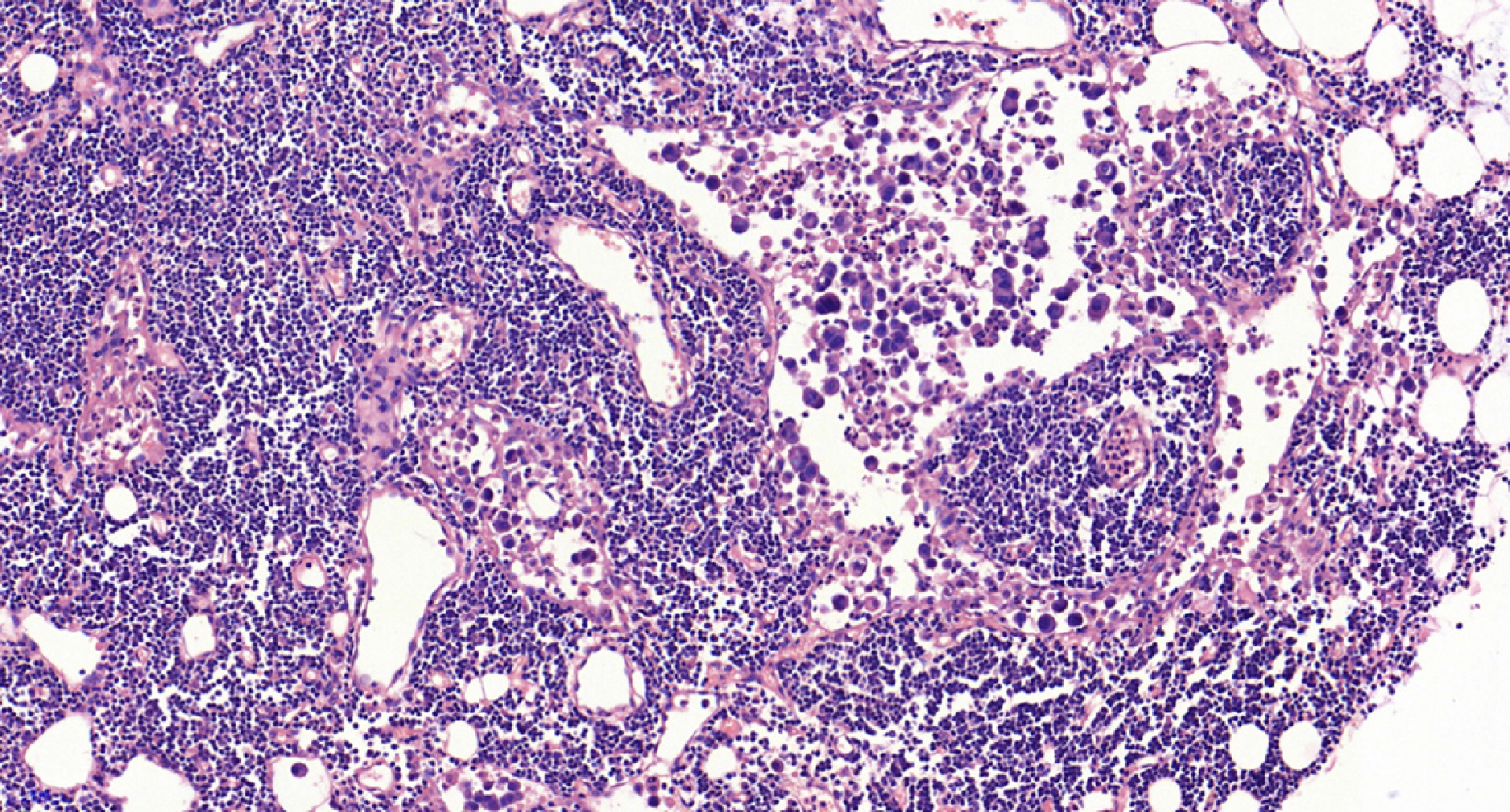

The included patients underwent gastrectomy with lymph node dissection. All operations were performed according to the 4th edition of the JGCA treatment guidelines[5]. The specimens were serially sectioned into 3-mm-thick slices, and two experienced pathologists individually examined the histological slides immediately after resection. The diagnostic criterion for LNM is the presence of cancerous tissue inside the lymph node capsule, as shown in Figures 1 and 2. We collected the clinical data, endoscopic features, and pathological characteristics of all enrolled patients. These data included age, sex, incidence of hypertension, heart disease and diabetes mellitus, drinking and smoking history, body mass index (BMI), family history, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level, tumor location, lesion size, macroscopic type, depth of invasion, number of tumors, presence of ulcers, tumor differentiation, Lauren type, presence of lymphovascular invasion (LVI), perineural invasion, and LNM.

Based on the distribution of gastric glands, we classified the tumor locations as cardia, fundus/corpora, or angle/antrum. According to the Paris endoscopic classification, the macroscopic features of EGC were divided into the following five subtypes: Type 0-I (protruded), type 0-IIa (superficial elevated), type 0-IIb (flat), type 0-IIc (superficial depressed), and type 0-III (excavated)[13]. Tumors were also graded as small (≤ 20 mm), medium (20-30 mm), and large (≥ 30 mm) to further analyze the indications for ESD. For invasion depth, submucosal lesions were classified into two groups: SM1 (≤ 500 μm depth of invasion) and SM2 (> 500 μm depth of invasion). In accordance with the JGCA, when multiple lesions were present, the tumor with the most advanced T category (or the largest lesion when the T stages were identical) was classified[2].

Statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS software (SPSS, version 23.0, Chicago, IL, United States). Continuous variables, such as age and BMI, were translated into categorical variables. For age, we calculated the mean value (59.25 years) of the patients and set 60 years as the cut-off value. According to the criteria for obesity, the enrolled patients were divided into a nonobesity group (BMI < 28) and an obesity group (BMI ≥ 28). Differences among categorical variables associated with predictors and LNM were assessed using a chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, and variables that were significant in the univariate analysis were subsequently entered into a multivariate logistic regression model for analysis of independent risk factors for LNM in EGC. The association between variables and LNM was described by an odds ratio (OR) and a 95% confidence interval (CI). P < 0.05 (two-sided) was considered statistically significant.

The statistical methods and analyses of this study were reviewed by professor Xiao-Bin Zhou from the Department of Health Statistics, Qingdao University.

We assessed 12552 patients who underwent radical gastrectomy with lymph node dissection. A total of 1262 (10.1%) eligible EGC patients with LNM (n = 182) and without LNM (n = 1080) were included in this study. The sex distribution was 899 (71.2%) males and 363 (28.8%) females (ratio: 2.48:1), with an average age of 59.25 years (range, 24-90 years). Data on the clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. Patients with a CEA value that exceeded the normal level were more likely to have LNM, and this association was statistically significant (P = 0.007). However, other clinical parameters, such as age, sex, underlying diseases, lifestyle habits, family history, and Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection, failed to reach statistical significance.

| Total (n = 1262), n (%) | LNM negative (n = 1080), n (%) | LNM positive (n = 182), n (%) | Univariate OR (95%CI) | P-value | |

| Age (yr) | 0.090 | ||||

| ≤ 60 | 628 (49.8) | 548 (50.7) | 80 (44.0) | 1 | |

| > 60 | 634 (50.2) | 532 (49.3) | 102 (56.0) | 1.313 (0.960, 1.800) | |

| Sex | 0.239 | ||||

| Male | 899 (71.2) | 776 (71.9) | 123 (67.6) | 1 | |

| Female | 363 (28.8) | 304 (28.1) | 59 (32.4) | 0.817 (0.580, 1.150) | |

| Hypertension | 0.554 | ||||

| Absence | 958 (75.9) | 823 (76.2) | 135 (74.2) | 1 | |

| Presence | 304 (24.1) | 257 (23.8) | 47 (25.8) | 1.115 (0.78, 1.60) | |

| Heart disease | 0.449 | ||||

| Absence | 1146 (90.8) | 978 (90.4) | 168 (92.3) | 1 | |

| Presence | 116 (9.2) | 102 (9.6) | 14 (7.7) | 0.799 (0.446, 1.430) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.933 | ||||

| Absence | 1142 (90.5) | 977 (90.5) | 165 (90.7) | 1 | |

| Presence | 120 (9.5) | 103 (9.5) | 17 (9.3) | 0.977 (0.570, 1.675) | |

| BMI | 0.086 | ||||

| ≤ 28 | 1134 (89.9) | 964 (89.3) | 170 (93.4) | 1 | |

| > 28 | 128 (10.1) | 116 (10.7) | 12 (6.6) | 0.587 (0.317, 1.086) | |

| Drinking | 0.104 | ||||

| Absence | 827 (65.6) | 698 (64.7) | 129 (70.9) | 1 | |

| Presence | 434 (34.4) | 381 (35.3) | 53 (29.1) | 0.753 (0.534, 1.061) | |

| Smoking | 0.138 | ||||

| Absence | 692 (54.8) | 583 (54.0) | 109 (59.9) | 1 | |

| Presence | 570 (45.2) | 497 (46.0) | 73 (40.1) | 0.786 (0.571, 1.082) | |

| Family history | 0.872 | ||||

| Absence | 1011 (80.1) | 866 (80.2) | 145 (79.7) | 1 | |

| Presence | 251 (19.9) | 214 (19.8) | 37 (20.3) | 1.033 (0.699, 1.526) | |

| H. pylori infection | 0.225 | ||||

| Negative | 634 (50.2) | 535 (49.5) | 99 (54.4) | 1 | |

| Positive | 628 (49.8) | 545 (50.5) | 83(45.6) | 0.823 (0.601, 1.128) | |

| CEA | 0.007 | ||||

| Negative | 960 (76.1) | 836 (77.4) | 124 (68.1) | 1 | |

| Positive | 302 (23.9) | 244 (22.6) | 58 (31.9) | 1.603 (1.137, 2.258) | |

According to further analysis, no LNM metastasis was observed in patients who met the absolute indications for ESD (0/90). However, LNM occurred in a few patients (4/311) who met the following expanded indications for ESD: (1) Differentiated mucosal tumors, ≤ 30 mm in size, without LVI, and with ulceration (3/86 cases, 3.5%); (2) Differentiated mucosal tumors, without ulcer and LVI, and of any size (1/32 cases, 3.1%); (3) Undifferentiated mucosal tumors without ulcer and LVI, and ≤ 20 mm in size (0/110 cases, 0%); and (4) Differentiated tumors with SM1 invasion, no LVI, and ≤ 30 mm in size (0/83 cases, 0%). As shown in Table 2, patients who met the surgical indications had a higher risk of LNM (P < 0.001). Table 3 contains more details on the frequency of LNM among EGC patients who met the indications for ESD.

| LNM (%) | 95%CI | P-value | |

| Absolute indications for ESD | 0/90 (0.0) | 0%-4.1% | < 0.001 |

| Expanded indications for ESD | 4/311 (1.3) | 0.35%-3.29% | |

| Surgical indications | 178/861 (20.7) | 17.75%-23.94% |

| LNM negative | LNM positive | LNM rate (%) | 95%CI | P-value | |

| Ab (n = 90) | 90 | 0 | 0.0 | 0%-4.1% | 0.021 |

| Ex1 (n = 86) | 83 | 3 | 3.5 | 0.75%-10.56% | |

| Ex2 (n = 32) | 31 | 1 | 3.1 | 0.08%-17.91% | |

| Ex3 (n = 110) | 110 | 0 | 0 | 0%-3.35% | |

| Ex4 (n = 83) | 83 | 0 | 0 | 0%-4.44% |

The endoscopic features are shown in Table 4. More EGCs were in the angle/antrum of the stomach (n = 928, 73.5%) than in the cardia (n = 46, 3.6%) and in the fundus/corpora (n = 288, 22.8%). Forty-two (3.3%) patients had multifocal lesions. The univariate analysis revealed that the location and number of tumors were not significantly associated with LNM. Regarding tumor size, LNM occurred significantly more frequently in patients with medium (P = 0.016) or large (P = 0.000) tumors than in patients with small tumors. With regard to macroscopic features, type IIc (n = 486, 38.5%) occurred most frequently among the five subtypes, but type III (n = 481, 38.1%) occurred more frequently in patients with LNM (P = 0.001). Ulcerative lesions also occurred more frequently in patients with LNM (P = 0.013).

| Total (n = 1262), n (%) | LNM negative (n = 1080), n (%) | LNM positive (n = 182), n (%) | Univariate OR (95%CI) | P-value | |

| Location | 0.462 | ||||

| Cardia | 46 (3.6) | 40 (3.7) | 6 (3.3) | 1 | |

| Fundus/corpora | 288 (22.8) | 240 (22.2) | 48 (26.4) | 1.333 (0.535, 3.320) | 0.537 |

| Angle/antrum | 928 (73.5) | 800 (74.1) | 128 (70.3) | 1.067 (0.443, 2.567) | 0.885 |

| Lesion size | < 0.001 | ||||

| Small (≤ 20 mm) | 761 (60.3) | 680 (63.0) | 81 (44.5) | 1 | |

| Middle (20-30 mm) | 285 (22.6) | 239 (22.1) | 46 (25.3) | 1.616 (1.093, 2.388) | 0.016 |

| Large (> 30 mm) | 216 (17.1) | 161 (14.9) | 55 (30.2) | 2.868 (1.955, 4.207) | < 0.001 |

| Macroscopic type | 0.001 | ||||

| 0-I(Protruded) | 86 (6.8) | 71 (6.6) | 15 (8.2) | 1.712 (0.823, 3.564) | 0.147 |

| 0-IIa (Elevated) | 36 (2.9) | 35 (3.2) | 1 (0.5) | 0.232 (0.030, 1.788) | 0.128 |

| 0-IIb (Flat) | 173 (13.7) | 154 (14.3) | 19 (10.4) | 1 | |

| 0-IIc (Depressed) | 486 (38.5) | 432 (40) | 54 (29.7) | 1.013 (0.582, 1.763) | 0.963 |

| 0-III (Excavated) | 481 (38.1) | 388 (35.9) | 93 (51.1) | 1.943 (1.146, 3.293) | 0.012 |

| Number of tumors | 0.191 | ||||

| Single | 1220 (96.7) | 1044 (96.7) | 176 (96.7) | 1 | |

| Multitude | 42 (3.3) | 36 (3.3) | 6 (3.3) | 1.724 (0.641, 4.635) | |

| Ulcer | 0.013 | ||||

| Absence | 558 (44.2) | 493 (45.6) | 65 (35.7) | 1 | |

| Presence | 704 (55.8) | 587 (54.4) | 117 (64.3) | 1.512 (1.091, 2.094) |

Among the 1262 EGC patients, 182 (14.4%) had LNM according to the pathological diagnostic criteria, including 123 (67.6%) with stage N1, 39 (21.4%) with stage N2, and 20 (11.0%) with stage N3 LNM according to the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Staging Manual. The mean number of metastatic lymph nodes was 2.8 (range, 1-17). Regarding lesion depth, 596 (47.2%) patients had tumors limited to the mucosal (M) layer, whereas 245 had SM1 (superficial submucosal) tumors (19.4%), and 421 had SM2 (deep submucosal) tumors (33.4%). The percentages of lymph node positivity were 5.2%, 19.6%, and 24.5% for M, SM1, and SM2, respectively. In terms of tumor differentiation, the undifferentiated type (n = 807, 63.9%) was the major histologic type of EGC based on the JGCA criteria and was significantly more likely to occur in patients with LNM than the differentiated type (n = 455, 36.1%) (P ˂ 0.001). Regarding cell histology, the patients with mucinous adenocarcinoma had a higher risk of LNM than patients with other histologic lesion types (P = 0.019). Based on the Lauren classification, LNM was observed more frequently in diffuse-type (DT) and mixed-type (MT) tumors (P = 0.003) than in intestinal-type (IT) tumors. Moreover, LNM was found significantly more frequently in patients with LVI (P ˂ 0.001) and perineural invasion (P ˂ 0.001) than in the patient subgroup without invasion. Additional detailed histopathologic features of the enrolled patients are summarized in Table 5.

| Total (n = 1262), n (%) | LNM negative (n = 1080), n (%) | LNM positive (n = 182), n (%) | Univariate OR (95%CI) | P-value | |

| Invasion depth | < 0.001 | ||||

| M | 596 (47.2) | 565 (52.3) | 31 (17.0) | 1 | |

| SM1 | 245 (19.4) | 197 (18.2) | 48 (26.4) | 4.441 (2.748, 7.176) | < 0.001 |

| SM2 | 421 (33.4) | 318 (29.4) | 103 (56.6) | 5.903 (3.862, 9.024) | < 0.001 |

| Differentiation | < 0.001 | ||||

| Differentiated | 455 (36.1) | 412 (38.1) | 43 (23.6) | 1 | |

| Undifferentiated | 807 (63.9) | 668 (61.9) | 139 (76.4) | 1.994 (1.386, 2.867) | |

| Histology | 0.019 | ||||

| Pap/Tub/Por | 1004 (79.6) | 866 (80.2) | 138 (75.8) | 1 | |

| Sig | 223 (17.7) | 190 (17.6) | 33 (18.1) | 1.090 (0.723, 1.644) | 0.681 |

| Muc | 35 (2.8) | 24 (2.2) | 11 (6.1) | 2.876 (1.378, 6.004) | 0.005 |

| LVI | < 0.001 | ||||

| Absence | 1104 (87.5) | 1021 (94.5) | 83 (45.6) | 1 | |

| Presence | 158 (12.5) | 59 (5.5) | 99 (54.4) | 20.641 (13.942, 30.559) | |

| Perineural invasion | < 0.001 | ||||

| Absence | 1181 (93.6) | 1026 (95) | 155 (85.2) | 1 | |

| Presence | 81 (6.4) | 54 (5.0) | 27 (14.8) | 3.310 (2.024, 5.413) | |

| Lauren's type | 0.003 | ||||

| Intestinal type | 500 (39.6) | 448 (41.5) | 52 (28.6) | 1 | |

| Diffuse type | 399 (31.6) | 335 (31.0) | 64 (35.2) | 1.646 (1.112, 2.437) | 0.013 |

| Mixed type | 363 (28.8) | 297 (27.5) | 66 (36.3) | 1.915 (1.294, 2.833) | 0.001 |

The univariate analysis results showed that 10 out of the 20 factors were significantly associated with a higher risk of LNM. The risk factors included high CEA levels, medium and large lesion sizes, excavated macroscopic type, presence of ulcers, deep submucosal invasion (SM1 and SM2), poor differentiation, LVI, mucinous adenocarcinoma, perineural invasion, and diffuse and mixed Lauren classifications.

Based on stepwise multivariate analysis, the significant independent risk factors for LNM in EGC were SM1 invasion (OR = 2.285, P = 0.030), SM2 invasion (OR = 3.230, P < 0.001), LVI (OR = 15.702, P < 0.001), pathological pattern of mucinous adenocarcinoma (OR = 2.823, P = 0.015), and lesion size over 30 mm (OR = 1.900, P = 0.006). The independent risk factors are listed in Table 6.

| Factor | OR (95%CI) | P-value |

| Lesion size | 0.025 | |

| Middle lesion size (20-30 mm) | 1.230 (0.774, 1.955) | 0.380 |

| Large lesion size (>30 mm) | 1.900 (1.197, 3.015) | 0.006 |

| Histology | 0.049 | |

| Sig | 1.146 (0.698, 1.881) | 0.590 |

| Muc | 2.823 (1.225, 6.505) | 0.015 |

| LVI | 15.702 (10.405, 23.695) | < 0.001 |

| Invasion depth | < 0.001 | |

| SM1 | 2.285 (1.317, 3.965) | 0.003 |

| SM2 | 3.230 (2.006, 5.201) | < 0.001 |

Following the introduction of the expanded indications for ESD, many studies have reevaluated the risk of LNM in EGC. A meta-analysis involving 9798 EGC patients showed that among the expanded indications for ESD, the inclusion of mucosal differentiated lesions of any size that were not ulcerated and of differentiated mucosal lesions < 30 mm that were ulcerated can be justified with a minimally increased risk. Nonetheless, the reasonableness of expanding the indications for ESD to include undifferentiated lesions smaller than 20 mm and differentiated lesions with slight submucosal invasion still requires careful investigation[6]. Our study demonstrated that the rate of LNM for patients who met the expanded indications for ESD was 4/311 (1.3%). No LNM occurred in patients who met the absolute indications. Similarly, reassessment of the expanded indications in Korea also showed an LNM rate of 2.4% among patients who met the expanded indications[14], which is inconsistent with the results of a large dataset from Japan that revealed no LNM in patients who met the expanded indications[15]. It is difficult to identify the reasons for this difference. A probable interpretation is that the existing indications are still not sufficiently comprehensive. The JGCA added invasion depth, ulceration, tumor size, differentiation, and LVI to its criteria for ESD. Based on our results, it is necessary to take the cellular histology of tumors into consideration when deciding upon the ESD indications. If ESD is performed in a more selective subgroup, the risk of LNM will likely be reduced. Therefore, predictive factors may be used to optimize the ESD criteria.

In line with other relevant studies, our study also concluded that deeper invasion significantly increased LNM risk. Additionally, the measurement of the width of the infiltration could be a useful additional parameter in the indications for supplemental gastrectomy after ESD. Therefore, a detailed measurement of invasion depth is truly necessary during the pathological evaluation of endoscopic-resected specimens[16]. Regarding lesion size, we found that larger tumor size was a significant predictor of regional LNM in our patients with EGC, which is similar to the conclusions of many other investigators[7,9,17-19]. However, the cut-off values varied among these studies, which increased the difficulty in determining a uniform standard. Two possible explanations can be identified: First, this parameter is a continuous variable, and the cut-off values are inconsistent in different studies; alternatively, the study subjects are diverse and included individuals with signet ring cell EGC, undifferentiated-type EGC, and mixed type EGC among others, which may also account for the difference.

In the latest gastric cancer treatment guidelines (2014 ver. 4), the JGCA noted that endoscopic dissection should be defined as noncurative if mucinous adenocarcinoma is found in the submucosal layer, regardless of whether the mucinous cells are believed to be derived from a differentiated or undifferentiated-type tumor. We conclude that the histological pattern of mucinous adenocarcinoma is an independent risk factor for LNM based on multivariate analysis, which provided powerful evidence to support this statement. With regard to signet ring cell carcinoma in EGC, it has been reported that the LNM rate of signet ring cell-type tumors is lower than that of other undifferentiated-type carcinomas and is equivalent to that of differentiated-type carcinomas[20], which is in line with our results. This suggests that ESD is more feasible for signet ring cell carcinoma compared with other early undifferentiated-type gastric carcinomas. However, the cellular histology of signet ring cell carcinoma is an important factor for LNM in EGC[21]. Huh et al[22] also stated that EGC with a mixed signet ring cell histology exhibited more aggressive behavior than pure tubular adenocarcinoma or pure signet ring cell carcinoma. Hence, a more accurate application of the classification of signet ring cell carcinoma could improve the ESD criteria.

In a previous study that focused on the prognosis of different types of gastric cancer as classified by the Lauren classification, patients with MT carcinomas were found to be significantly more likely to have LNM than patients with IT and DT carcinomas, which was also confirmed in our study. A possible explanation of this difference is that patients with MT tumors always exhibit severe characteristics, including larger lesion sizes and a higher frequency of spread into local lymphatic and venous vessels or regional lymph nodes[23]. In various clinical and pathological studies, LVI has been reported to be the strongest risk factor for nodal metastasis in EGC[24], and we confirmed this finding by showing that LVI predicted a high risk of LNM in EGC. However, unlike other risk factors that can be observed by endoscopic investigation and other auxiliary examinations, LVI is difficult to detect before the ER specimen is obtained. However, based on the criteria for local treatment, the presence of LVI commonly requires additional extended surgery, which is clinically significant. As shown in Table 3, every histopathological factor included in this study was significantly associated with LNM, which indicates that all of these factors are vitally important for performing an accurate pathological analysis after gastroscopic examination.

Researchers have previously concluded that the overall 3-year survival rate was higher in patients without LNM and that patients with LNM had a higher rate of tumor recurrence[25]. Several factors are associated with an increased rate of LNM. The risk factors varied in some relevant studies, but LVI, submucosal invasion, histological type, and tumor size were found to be significantly related to LNM in almost every study. Consistent with other studies[7,18,26], our study demonstrated that age, sex, tumor location, macroscopic type, presence of ulcers, tumor differentiation, Lauren type, and H. pylori infection were not independent risk factors for LNM, although some of these factors were statistically significant in the univariate analysis. Specifically, we analyzed other clinical features, such as drinking and smoking history, obesity, family history of tumors, and the levels of the tumor marker CEA, which is an innovative aspect of this study. In recent years, biomarkers have begun to play an increasingly important role in the detection and management of patients with gastrointestinal malignancies[27]. Serum CEA is considered a complementary test, although it is insufficient to diagnose EGC and LNM. In this study, a higher than normal CEA value was found to be statistically significant in univariate analysis, which attaches great importance to its preoperative detection. However, inconsistencies were found among the test items of the included patients, which made it difficult to perform an analysis of other less common tumor markers. Buckland et al[28] reported that nicotine and alcohol played an important role in the development of gastric cancer, and therefore, we further analyzed the relationships between drinking and smoking with LNM. Despite the lack of significant association between the occurrence of LNM and these lifestyle habits in this study, we cannot ignore these factors because the clinical data collected in retrospective studies may be incomplete. Although this research, to the best of our knowledge, involved the largest number of EGC patients in China, the limitation that it was a retrospective study at a single institution should still be noted. Therefore, a well-designed multicentric prospective study is needed.

In conclusion, the absolute indications for ESD can be applied to Chinese patients, while the feasibility of expanding these indications requires further investigation. The predictive factors for LNM included submucosal invasion depth, LVI, mucinous adenocarcinoma, and large lesion size. Taking the histology of tumors into consideration when deciding upon the ESD indications is therefore of great necessity.

The indications for endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) have been recently expanded to include larger, ulcerated, and undifferentiated mucosal lesions, and differentiated lesions with slight submucosal invasion. Despite the advantages over surgical procedures, lymph nodes cannot be removed by ESD. However, the risk of lymph node metastasis (LNM) is the most important consideration when deciding on a treatment strategy for early gastric cancer (EGC).

Evaluating the risk of LNM is critical for determining the best course of management for EGC patients. Unfortunately, the risk factors that have been identified in different studies are diverse, and whether patients who met the expanded indications for ESD can be managed safely remains controversial.

We aimed to determine whether the ESD indications are applicable to Chinese patients and to investigate the predictors of LNM in EGC. After working hard on this topic, we have re-evaluated and verified the current indications and guidelines for endoscopic treatment and analyzed the clinicopathological predictors of LNM, which provides strong evidence and reference to future research.

We retrospectively analyzed 12552 patients who underwent surgery for gastric cancer between June 2007 and December 2018 at the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University. A total of 1262 (10.1%) EGC patients were eligible for inclusion in this study. Data on the patients’ clinical, endoscopic, and histopathological characteristics were collected. The absolute and expanded indications for ESD were validated by regrouping the enrolled patients and determining the positive LNM results in each subgroup. Predictors of LNM in patients were evaluated by univariate and multivariate analyses. Specifically, we analyzed other clinical features, such as drinking and smoking history, obesity, family history of tumors, and the levels of the tumor marker carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), which is an innovative aspect of this study.

LNM was observed in 182 (14.4%) patients. No LNM was detected in the patients who met the absolute indications (0/90). LNM occurred in 4/311 (1.3%) patients who met the expanded indications. According to univariate analysis, LNM was significantly associated with positive tumor marker status, medium (20-30 mm) and large (>30 mm) lesion sizes, excavated macroscopic-type tumors, ulcer presence, submucosal invasion (SM1 and SM2), poor differentiation, lymphovascular invasion (LVI), perineural invasion, and diffuse and mixed Lauren’s types. Multivariate analysis demonstrated SM1 invasion (OR = 2.285, P = 0.03), SM2 invasion (OR = 3.230, P < 0.001), LVI (OR = 15.702, P < 0.001), mucinous adenocarcinoma (OR = 2.823, P = 0.015), and large lesion size (OR = 1.900, P = 0.006) to be independent risk factors. Also, the results of this research affirmed the feasibility of the absolute indications for ESD. However, whether it is reasonable to expand the indications remains to be further discussed.

The absolute indications for ESD can be applied to Chinese patients, while the feasibility of expanding these indications requires further investigation. The predictive factors for LNM included submucosal invasion depth, LVI, mucinous adenocarcinoma, and large lesion size. This study provides clinicians with important reference when evaluating the risk of LNM and determining the best course of management for EGC patients.

Besides invasion depth, LVI, and lesion size, taking the histology of tumors into consideration when deciding upon the ESD indications is vitally important. In addition, preoperative detection of tumor markers is of great necessity. The direction of the future research is to further optimize the ESD indications by analyzing the predictive factors for LNM in EGC. A well-designed multicentric prospective study is the best method for the future research.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Draganov PV, Friedel D S-Editor: Tang JZ L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Balakrishnan M, George R, Sharma A, Graham DY. Changing Trends in Stomach Cancer Throughout the World. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2017;19:36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 274] [Article Influence: 34.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:101-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2390] [Cited by in RCA: 2855] [Article Influence: 203.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Abdelfatah MM, Barakat M, Othman MO, Grimm IS, Uedo N. The incidence of lymph node metastasis in submucosal early gastric cancer according to the expanded criteria: a systematic review. Surg Endosc. 2019;33:26-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Isomoto H, Shikuwa S, Yamaguchi N, Fukuda E, Ikeda K, Nishiyama H, Ohnita K, Mizuta Y, Shiozawa J, Kohno S. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: a large-scale feasibility study. Gut. 2009;58:331-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 470] [Cited by in RCA: 518] [Article Influence: 32.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2014 (ver. 4). Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:1-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1575] [Cited by in RCA: 1904] [Article Influence: 238.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Abdelfatah MM, Barakat M, Lee H, Kim JJ, Uedo N, Grimm I, Othman MO. The incidence of lymph node metastasis in early gastric cancer according to the expanded criteria in comparison with the absolute criteria of the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87:338-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wang Z, Zhang X, Hu J, Zeng W, Liang J, Zhou H, Zhou Z. Predictive factors for lymph node metastasis in early gastric cancer with signet ring cell histology and their impact on the surgical strategy: analysis of single institutional experience. J Surg Res. 2014;191:130-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ahmad R, Setia N, Schmidt BH, Hong TS, Wo JY, Kwak EL, Rattner DW, Lauwers GY, Mullen JT. Predictors of Lymph Node Metastasis in Western Early Gastric Cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20:531-538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kunisaki C, Takahashi M, Nagahori Y, Fukushima T, Makino H, Takagawa R, Kosaka T, Ono HA, Akiyama H, Moriwaki Y, Nakano A. Risk factors for lymph node metastasis in histologically poorly differentiated type early gastric cancer. Endoscopy. 2009;41:498-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Suzuki H, Oda I, Abe S, Sekiguchi M, Mori G, Nonaka S, Yoshinaga S, Saito Y. High rate of 5-year survival among patients with early gastric cancer undergoing curative endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastric Cancer. 2016;19:198-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zhang Y, Liu Y, Zhang J, Wu X, Ji X, Fu T, Li Z, Wu Q, Bu Z, Ji J. Construction and external validation of a nomogram that predicts lymph node metastasis in early gastric cancer patients using preoperative parameters. Chin J Cancer Res. 2018;30:623-632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wang H, Zhang H, Wang C, Fang Y, Wang X, Chen W, Liu F, Shen K, Qin X, Shen Z, Sun Y. Expanded endoscopic therapy criteria should be cautiously used in intramucosal gastric cancer. Chin J Cancer Res. 2016;28:348-354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions: esophagus, stomach, and colon: November 30 to December 1, 2002. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:S3-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1117] [Cited by in RCA: 1315] [Article Influence: 59.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 14. | Kang HJ, Kim DH, Jeon TY, Lee SH, Shin N, Chae SH, Kim GH, Song GA, Kim DH, Srivastava A, Park DY, Lauwers GY. Lymph node metastasis from intestinal-type early gastric cancer: experience in a single institution and reassessment of the extended criteria for endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:508-515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gotoda T, Yanagisawa A, Sasako M, Ono H, Nakanishi Y, Shimoda T, Kato Y. Incidence of lymph node metastasis from early gastric cancer: estimation with a large number of cases at two large centers. Gastric Cancer. 2000;3:219-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1308] [Cited by in RCA: 1322] [Article Influence: 52.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zhao B, Zhang J, Zhang J, Luo R, Wang Z, Xu H, Huang B. Risk Factors Associated with Lymph Node Metastasis for Early Gastric Cancer Patients Who Underwent Non-curative Endoscopic Resection: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2019;23:1318-1328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lee JH, Choi IJ, Han HS, Kim YW, Ryu KW, Yoon HM, Eom BW, Kim CG, Lee JY, Cho SJ, Kim YI, Nam BH, Kook MC. Risk of lymph node metastasis in differentiated type mucosal early gastric cancer mixed with minor undifferentiated type histology. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:1813-1819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Fang WL, Huang KH, Lan YT, Chen MH, Chao Y, Lo SS, Wu CW, Shyr YM, Li AF. The Risk Factors of Lymph Node Metastasis in Early Gastric Cancer. Pathol Oncol Res. 2015;21:941-946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Du MZ, Gan WJ, Yu J, Liu W, Zhan SH, Huang S, Huang RP, Guo LC, Huang Q. Risk factors of lymph node metastasis in 734 early gastric carcinoma radical resections in a Chinese population. J Dig Dis. 2018;19:586-595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kook MC. Risk Factors for Lymph Node Metastasis in Undifferentiated-Type Gastric Carcinoma. Clin Endosc. 2019;52:15-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kim YH, Park JH, Park CK, Kim JH, Lee SK, Lee YC, Noh SH, Kim H. Histologic purity of signet ring cell carcinoma is a favorable risk factor for lymph node metastasis in poorly cohesive, submucosa-invasive early gastric carcinoma. Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:583-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Huh CW, Jung DH, Kim JH, Lee YC, Kim H, Kim H, Yoon SO, Youn YH, Park H, Lee SI, Choi SH, Cheong JH, Noh SH. Signet ring cell mixed histology may show more aggressive behavior than other histologies in early gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107:124-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zheng HC, Li XH, Hara T, Masuda S, Yang XH, Guan YF, Takano Y. Mixed-type gastric carcinomas exhibit more aggressive features and indicate the histogenesis of carcinomas. Virchows Arch. 2008;452:525-534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ono H, Yao K, Fujishiro M, Oda I, Nimura S, Yahagi N, Iishi H, Oka M, Ajioka Y, Ichinose M, Matsui T. Guidelines for endoscopic submucosal dissection and endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer. Dig Endosc. 2016;28:3-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 354] [Cited by in RCA: 404] [Article Influence: 44.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Li X, Liu S, Yan J, Peng L, Chen M, Yang J, Zhang G. The Characteristics, Prognosis, and Risk Factors of Lymph Node Metastasis in Early Gastric Cancer. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2018;2018:6945743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Haruta H, Hosoya Y, Sakuma K, Shibusawa H, Satoh K, Yamamoto H, Tanaka A, Niki T, Sugano K, Yasuda Y. Clinicopathological study of lymph-node metastasis in 1,389 patients with early gastric cancer: assessment of indications for endoscopic resection. J Dig Dis. 2008;9:213-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Duffy MJ, Lamerz R, Haglund C, Nicolini A, Kalousová M, Holubec L, Sturgeon C. Tumor markers in colorectal cancer, gastric cancer and gastrointestinal stromal cancers: European group on tumor markers 2014 guidelines update. Int J Cancer. 2014;134:2513-2522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 253] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 22.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 28. | Buckland G, Travier N, Huerta JM, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Siersema PD, Skeie G, Weiderpass E, Engeset D, Ericson U, Ohlsson B, Agudo A, Romieu I, Ferrari P, Freisling H, Colorado-Yohar S, Li K, Kaaks R, Pala V, Cross AJ, Riboli E, Trichopoulou A, Lagiou P, Bamia C, Boutron-Ruault MC, Fagherazzi G, Dartois L, May AM, Peeters PH, Panico S, Johansson M, Wallner B, Palli D, Key TJ, Khaw KT, Ardanaz E, Overvad K, Tjønneland A, Dorronsoro M, Sánchez MJ, Quirós JR, Naccarati A, Tumino R, Boeing H, Gonzalez CA. Healthy lifestyle index and risk of gastric adenocarcinoma in the EPIC cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:598-606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |