Published online Sep 14, 2019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i34.5197

Peer-review started: July 1, 2019

First decision: August 2, 2019

Revised: August 12, 2019

Accepted: August 19, 2019

Article in press: August 19, 2019

Published online: September 14, 2019

Processing time: 75 Days and 22.6 Hours

Colorectal high-grade neuroendocrine neoplasms (HGNENs) are rare and constitute less than 1% of all colorectal malignancies. Based on their morphological differentiation and proliferation identity, these neoplasms present heterogeneous clinicopathologic features. Opinions regarding treatment strategies for and improvement of the clinical outcomes of these patients remain controversial.

To delineate the clinicopathologic features of and explore the prognostic factors for this rare malignancy.

This observational study reviewed the data of 72 consecutive patients with colorectal HGNENs from three Chinese hospitals between 2000 and 2019. The clinicopathologic characteristics and follow-up data were carefully collected from their medical records, outpatient reexaminations, and telephone interviews. A survival analysis was conducted to evaluate their outcomes and to identify the prognostic factors for this disease.

According to the latest recommendations for the classification and nomenclature of colorectal HGNENs, 61 (84.7%) patients in our cohort had poorly differentiated neoplasms, which were categorized as high-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas (HGNECs), and the remaining 11 (15.3%) patients had well differentiated neoplasms, which were categorized as high-grade neuroendocrine tumors (HGNETs). Most of the neoplasms (63.9%) were located at the rectum. More than half of the patients (51.4%) presented with distant metastasis at the date of diagnosis. All patients were followed for a median duration of 15.5 mo. In the entire cohort, the median survival time was 31 mo, and the 3-year and 5-year survival rates were 44.3% and 36.3%, respectively. Both the univariate and multivariate analyses demonstrated that increasing age, HGNEC type, and distant metastasis were risk factors for poor clinical outcomes.

Colorectal HGNENs are rare and aggressive malignancies with poor clinical outcomes. However, patients with younger age, good morphological differentiation, and without metastatic disease can have a relatively favorable prognosis.

Core tip: Colorectal high-grade neuroendocrine neoplasms (HGNENs) are aggressive malignancies with an extremely low incidence. Many issues, such as their classification and therapy strategies, have been controversial for a long time. We conducted this study to delineate their clinicopathologic features and clinical outcomes. There is a trend to categorize colorectal HGNENs with good morphological differentiation as a subgroup different from high-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas in the newest World Health Organization classification. We introduced this classification into our study and compared the prognoses of different subgroups.

- Citation: Wang ZJ, An K, Li R, Shen W, Bao MD, Tao JH, Chen JN, Mei SW, Shen HY, Ma YB, Zhao FQ, Wei FZ, Liu Q. Analysis of 72 patients with colorectal high-grade neuroendocrine neoplasms from three Chinese hospitals. World J Gastroenterol 2019; 25(34): 5197-5209

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v25/i34/5197.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i34.5197

Colorectal high-grade neuroendocrine neoplasm (HGNEN) is a rare malignancy originating from neuroendocrine cells in the colon and rectum, and it constitutes less than 1% of all colorectal carcinomas[1,2]. Based on the 2010 World Health Organization (WHO) classification, neuroendocrine neoplasms with a high mitotic rate (over 20/10 high power fields) or Ki-67 labeling index (over 20%) were defined as HGNEN or neuroendocrine neoplasm (NEN) G3, including small-cell and large-cell subtypes. All colorectal high-grade neuroendocrine neoplasms (HGNENs) were regarded as poorly differentiated. Therefore, the term HGNEN was synonymous with high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma (HGNEC)[3]. However, the histological grade is not always in line with the degree of morphological differentiation; in some patients, tumors are high grade but present good differentiation[4]. These patients show significantly different tumor biology, behavior, and prognosis compared with those with poorly differentiated HGNENs. Therefore, the consensus has been that colorectal HGNENs are not a homogenous entity[5]. In the 2017 WHO classification for pancreatic NEN, neuroendocrine tumor G3 (NET G3) was put forward as a new term and was defined as a new subgroup of pancreatic HGNENs with good differentiation, whereas neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) only refers to poorly differentiated G3 pancreatic HGNENs. HGNEN or NEN G3 included both NET G3 and NEC. There is a trend towards introducing this new classification system into the management of colorectal HGNENs in the near future[6]. At the 16th annual European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS) Conference in 2019, Professor Aurel Perren presented “New WHO Classification-Important News”, stating that the terminology of NET G3 is extended to other primary sites, including the colon and rectum. According to the latest updates on the classification and grading of colorectal NENs, all cases in the present study were categorized as well-differentiated subtype (NET G3) and poorly differentiated subtype (NEC) on the basis of histomorphology.

Similar to small cell lung cancer, colorectal HGNENs are highly aggressive with a dismal prognosis, and over half of the patients have distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis[7]. The clinical manifestations are nonspecific, including hematochezia, abdominal pain, changes in bowel habits, and obstruction. Carcinoid syndrome is rare because most colorectal HGNENs are nonfunctional[8]. For early and small lesions, colorectal HGNENs usually present typical endoscopic features that are different from colorectal adenocarcinomas. They arise in the deeper layers of the intestinal mucosa and appear as smooth sessile lesions with normal overlying mucosa. Yellow mucosal discolouration might be observed in cases with positive expression of chromogranin[9,10]. However, most cases present large and advanced lesions at the date of diagnosis, and these lesions show no significantly different endoscopic presentations compared with other colorectal tumors. Therefore, it is difficult to distinguish HGNENs from common adenocarcinoma by a routine diagnostic technique. Immunohistochemical evaluation is necessary since HGNENs have special neuroendocrine markers, such as synaptophysin, chromogranin A, and neuron-specific enolase[11]. Due to the extremely low incidence rate of HGNENs, there are very few related prospective clinical studies; most studies are case reports or retrospective studies with small samples from single institutions in Western countries. As a consequence, no standard treatment guidelines have been made, and the efficacy of surgery and chemotherapy remains controversial.

Since most previous studies are case reports or small sample reports from single centers and Western countries, we conducted a multicenter prospective study and enrolled 72 patients from three different Chinese hospitals, aiming to improve our understanding of the clinicopathologic features and oncologic prognosis of patients with colorectal HGNENs.

Our study was approved by the ethics committee of the National Cancer Center and was performed according to the Helsinki Declaration of the World Medical Association. All patients signed an informed consent form before the study. We reviewed the electronic medical records from three different Chinese institutions and enrolled 72 consecutive colorectal HGNEN patients from January 2000 to January 2019, including 47 from the Cancer Hospital Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, 20 from China-Japan Friendship Hospital, and 5 from Beijing Hospital. Information regarding patient demographics, clinicopathologic features, treatment modalities, and oncologic outcomes was carefully collected and analyzed. All cases were definitively diagnosed with colorectal HGNEN through colonoscopy, abdominal and pelvic enhanced computed tomography scans, tissue biopsy, pathological examination, and immunohistochemical evaluation. All patients were confirmed to have a high mitotic rate (over 20/10 high power fields) and/or Ki-67 labeling index (over 20%). Moreover, cases with a component of adenocarcinoma or squamous carcinoma were excluded.

Our study received statistical review by one biomedical statistician in our institution. All data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 24.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Quantitative data that followed the normal distribution are expressed as the median ± standard deviation, while quantitative data that did not follow the normal distribution are expressed as median and range. Qualitative data and ordinal data are presented as the number of cases and percentages. Survival time was defined as the time interval between the date of pathological diagnosis and death. Survival rates were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method and further compared through the log-rank test. In addition, multivariate analysis was performed using the Cox proportional hazards regression model to identify the independent prognostic factors. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The patients’ characteristics are presented in Table 1. A total of 72 patients with a median age of 59.5 years old (range, 18-82 years old), including 52 (72.2%) males and 20 (27.8%) females, were enrolled in our study. The average body mass index (BMI) was 23.8 ± 3.4 kg/m2. The common symptoms were hematochezia (37, 51.4%), abdominal pain (23, 31.9%), changes in bowel habits (23, 31.9%), abdominal distention (5, 9.6%), weight loss (3, 4.2%), and anemia (2, 2.8%). Two patients were asymptomatic, and cancer was detected through routine health examinations. No patients had functional tumors or presented with carcinoid syndrome. The rectum (n = 46, 63.9%), especially low rectum, was the most common primary site. Among the 46 patients with rectal HGNENs, 28 (60.9%) were located in the low rectum. More than half of the patients (51.4%) presented metastatic diseases at the date of diagnosis, and the liver and distant lymph nodes were the two most common metastatic sites.

| Characteristic | Patients (n = 72) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 52 (72.2) |

| Female | 20 (27.8) |

| Age [yr, median (range)] | 59.5 (18-82) |

| BMI (kg/m2, mean ± SD) | 23.8 ± 3.4 |

| Symptoms, n (%) | |

| Hematochezia | 37 (51.4) |

| Abdominal pain | 23 (31.9) |

| Changes in bowel habits | 23 (31.9) |

| Obstruction | 12 (16.7) |

| Abdominal distention | 5 (9.6) |

| Weight loss | 3 (4.2) |

| Anemia | 2 (2.8) |

| Carcinoid syndrome | 0 |

| Asymptomatic | 2 (2.8) |

| Family history of cancer, n (%) | |

| Yes | 11 (15.3) |

| No | 60 (83.3) |

| Unrecorded | 1 (1.4) |

| History of colorectal polyps, n (%) | |

| Yes | 24 (33.3) |

| No | 27 (37.5) |

| Unrecorded | 21 (29.2) |

| Smoking history, n (%) | |

| Yes | 28 (38.9) |

| No | 42 (58.3) |

| Unrecorded | 2 (2.8) |

| Drinking history, n (%) | |

| Yes | 24 (33.3) |

| No | 45 (62.5) |

| Unrecorded | 3 (4.2) |

| Primary sites, n (%) | |

| Rectum | 46 (63.9) |

| Rectosigmoid junction | 2 (2.8) |

| Sigmoid | 5 (6.9) |

| Descending colon | 4 (5.6) |

| Transverse colon | 2 (2.8) |

| Ascending colon | 9 (12.5) |

| Cecum | 4 (5.6) |

| Distance of tumor from the anal verge [(for rectal carcinoma, n = 46), n (%)] | |

| 0-5 cm | 28 (60.9) |

| 5-10 cm | 14 (19.4) |

| 10-15 cm | 2 (2.8) |

| Unrecorded | 2 (2.8) |

| Tumor size [median (range), cm] | 5.0 (1.0-15.0) |

| Tumor stage, n (%) | |

| I | 4 (5.6) |

| II | 4 (5.6) |

| III | 27 (37.5) |

| IV | 37 (51.4) |

| Site of distant metastases, n (%) | |

| Liver | 27 (37.5) |

| Liver only | 12 (16.6) |

| Distant lymph nodes | 15 (20.8) |

| Peritoneum | 5 (6.9) |

| Bone | 5 (6.9) |

| Lung | 1 (1.4) |

| Pancreas | 1 (1.4) |

| Increase of pretreatment blood LDH, n (%) | |

| Yes | 10 (13.9) |

| No | 29 (40.3) |

| Unrecorded | 33 (45.8) |

The pathological features and immunohistochemical results are listed in Table 2. Of the 72 patients, 61 (84.7%) had poorly differentiated tumors classified as NECs, and the remaining 11 patients had well differentiated tumors classified as NETs G3. Among the 61 NEC patients, 18 (29.5%) and 18 (29.5%) had large cell and small cell subtypes, respectively. Cancers of the remaining 25 (41%) patients were not further categorized in the medical records. Regarding the general shape of neoplasms in the 58 evaluable patients, one half were ulcerative, and the other half were the protruding type. All the patients received immunohistochemical evaluation, and the median value of the Ki67 index was 70% in our cohort. Synaptophysin, chromogranin, neuron-specific enolase, and CD 56 were positive in 94%, 57.6%, 64.3%, and 82.4%, respectively, of all evaluable cases. CDX-2 and TTF-1 were evaluated in 29 and 13 patients, respectively, and the positive rates were 62.1% and 15.4%, respectively. Extramural vascular invasion (EMVI) and perineural invasion were observed in 76.3% and 21.6% of evaluable patients, respectively.

| Histology, n (%) | Patients (n = 72) |

| NEC | 61 (84.7) |

| NET G3 | 11 (15.3) |

| General classification of tumor, n (%) | |

| Ulcerative type | 29 (40.3) |

| Protruding type | 29 (40.3) |

| Unrecorded | 14 (19.4) |

| Synaptophysin, n (%) | |

| Positive | 63 (87.5) |

| Negative | 4 (5.6) |

| Unrecorded | 5 (6.9) |

| Chromogranin, n (%) | |

| Positive | 38 (52.8) |

| Negative | 28 (38.9) |

| Unrecorded | 6 (8.3) |

| Neuron specific enolase, n (%) | |

| Positive | 9 (12.5) |

| Negative | 5 (6.9) |

| Unrecorded | 58 (80.6) |

| CD56, n (%) | |

| Positive | 42 (58.3) |

| Negative | 9 (12.5) |

| Unrecorded | 21 (29.2) |

| CDX-2, n (%) | |

| Positive | 18 (25) |

| Negative | 11 (15.3) |

| Unrecorded | 43 (59.7) |

| TTF-1, n (%) | |

| Positive | 2 (2.8) |

| Negative | 11 (15.3) |

| Unrecorded | 59 (81.9) |

| Ki 67 (median, range) | 70% (25%-95%) |

| EMVI, n (%) | |

| Yes | 29 (40.3) |

| No | 9 (12.5) |

| Unrecorded | 34 (47.2) |

| Perineural invasion, n (%) | |

| Yes | 8 (11.1) |

| No | 29 (40.3) |

| Unrecorded | 35 (48.6) |

Of the 35 patients without distant metastasis, 1 received only chemotherapy. This patient underwent a cycle of combination chemotherapy of cisplatin and etoposide and two cycles of single-agent irinotecan. However, the neoplasm progressed, and the patient died in the hospital 3 mo after the date of diagnosis. The other 34 patients underwent surgical resection of tumors, including 2 patients who underwent local excision. Six patients received surgery alone. Five patients received neoadjuvant therapy, and all responded to therapy, with one achieving a pathologic complete response and surviving free from recurrence for 14 mo by the end of follow-up. Twenty-eight patients received adjuvant therapy. Five patients received both neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatment (Table 3).

| Treatment strategy | Patients (n = 35) |

| Nonsurgical treatment | 1 |

| Surgery alone | 6 |

| Surgery + adjuvant treatment | 23 |

| Neoadjuvant treatment + surgery + adjuvant treatment | 5 |

Of the 37 patients with distant metastasis at the date of diagnosis, 17 underwent surgery and received primary site resection, 17 received palliative chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy alone, and 3 did not receive any oncological treatment. The details of palliative chemotherapy were evaluable for 28 cases. Twenty-eight cases received first-line palliative chemotherapy, and 9 (32.1%) cases were responsive. Twelve of 28 (42.9%) patients received fluorouracil (5-FU)-based chemotherapy [capecitabine plus oxaliplatin (n = 5), oxaliplatin, leucovorin, and fluorouracil (n = 3), oxaliplatin plus fluorouracil (n = 1), irinotecan plus tegafur/gimeracil/oteracil potassium (S-1) (n = 1), capecitabine plus temozolomide (TemCap) (n = 1), and S-1 (n = 1)], and 1 patient (8.3%) responded. The remaining 16 (57.1%) patients received platinum-based chemotherapy [cisplatin plus etoposide (EP) (n = 14), oxaliplatin plus etoposide (n = 1), carboplatin plus etoposide (n = 1)], and 8 (50%) cases responded. Thirteen and 9 cases received second-line and third-line palliative chemotherapy, and the responsive rates were 23.1% and 22.2%, respectively.

Of the three patients who did not receive any oncological treatment, one survived for only 1 mo, one survived for 3 mo, and one was lost to follow-up.

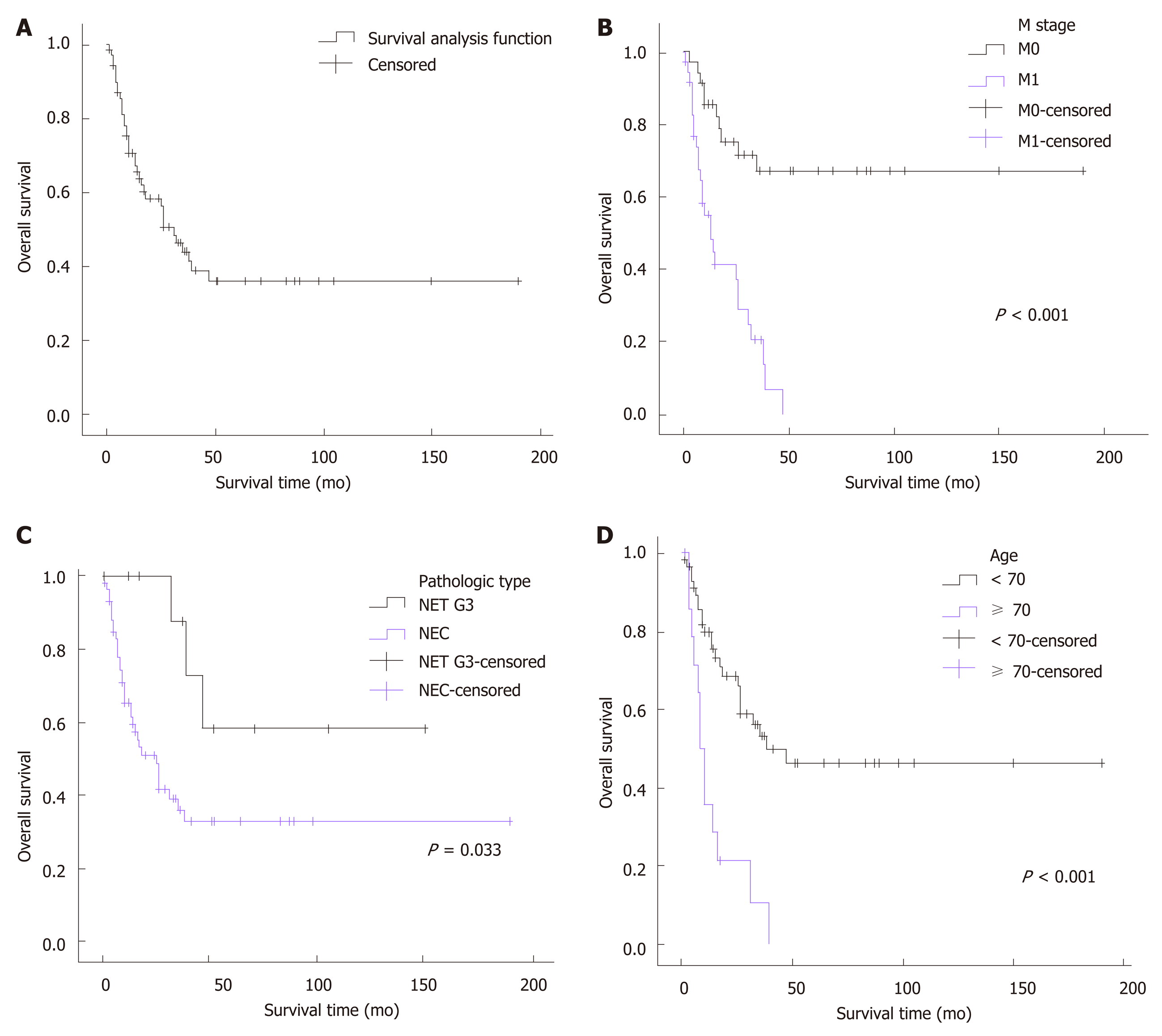

All patients were followed for a median duration of 15.5 mo (range, 1-190 mo). A median survival of 31 mo was achieved in the whole cohort, and the 3-year and 5-year survival rates were 44.3% and 36.3%, respectively. A significantly decreased median survival of 13 mo was observed for the patients with metastatic disease. Since more than half of the patients without distant metastasis (67%) survived through the end of follow-up, the median survival of these patients could not be calculated. Univariate analysis demonstrated that age (P < 0.001), pathologic type (P = 0.033), neoplasm macroscopic type (P = 0.037), distant metastasis (P < 0.001), positive EMVI (P = 0.047), elevation of pretreatment serum lactate dehydrogenase (P = 0.015), and resection of the primary site (P < 0.001) were associated with the overall survival of patients with colorectal HGNEC (Figure 1). For unclear reasons, no significant survival advantage was found in patients with a low Ki-67 index (<55%), as reported in previous studies. To identify the independent prognostic factors, multivariate analysis was subsequently performed. Based on previous studies and knowledge, we enrolled 6 variables: Gender, age, tumor location, pathological type, distant metastasis, and resection of the primary site. Given the missing data for the pretreatment level of serum lactate dehydrogenase, tumor macroscopic type, EMVI, and Ki-67 index, these variables were not included in the multivariate analysis. Consequently, age ≥ 70 [hazard ratio (HR) = 3.926, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.740-8.858, P = 0.001], pathologic type of NEC (HR = 6.647, 95%CI: 1.759-25.119, P = 0.005), and distant metastasis (HR = 6.356, 95%CI: 2.543-15.889, P < 0.001) were confirmed to be independent risk factors for poor prognosis (Table 4).

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| Median OS | P-value | HR (95%CI) | P-value | |

| Sex | 0.095 | 1.374 (0.664-2.845) | 0.392 | |

| Male | 39 | |||

| Female | 18 | |||

| Age (yr) | <0.001 | 3.926 (1.740-8.858) | 0.001 | |

| <70 | 47 | |||

| ≥70 | 8 | |||

| Radical surgery | <0.001 | 0.778 (0.338-1.792) | 0.555 | |

| Yes | 39 | |||

| No | 8 | |||

| Tumor location | 0.386 | 1.592 (0.738-3.434) | 0.236 | |

| Colon | 15 | |||

| Rectum | 35 | |||

| Gross type | 0.037 | |||

| Ulcerative | 18 | |||

| Protruding | imponderable | |||

| Distant metastasis | <0.001 | 6.356 (2.543-15.889) | <0.001 | |

| Yes | 13 | |||

| No | imponderable | |||

| Pathologic type | 0.033 | 6.647 (1.759-25.119) | 0.005 | |

| NEC | 25 | |||

| NET G3 | imponderable | |||

| Ki67 index | 0.893 | |||

| <55% | 39 | |||

| ≥55% | 35 | |||

| EMVI | 0.047 | |||

| Yes | 26 | |||

| No | Imponderable | |||

| Perineural invasion | 0.944 | |||

| Yes | 26 | |||

| No | 39 | |||

| Pretreatment bloodLDH level | 0.015 | |||

| Elevated | 7 | |||

| Not elevated | 26 | |||

Colorectal HGNEN is an extremely rare malignancy with an incidence rate ranging from 1 to 2 per million, constituting less than 1% of all colorectal malignancies. However, its incidence rate has been increasing in the past decades, and the reported annual increase rate ranges from 2.2% to 9.4%[12,13]. Moreover, its clinical prognosis is much worse compared to colorectal adenocarcinoma. It seems that the advances in the study of colorectal adenocarcinoma did not benefit the prevention and treatment of colorectal HGNENs. Our multicenter retrospective study delineated the clinicopathologic features, clinical outcomes, and prognostic factors for this rare tumor.

In previous reports, rectal HGNEN was the most frequent and accounted for 26.5% to 64% of all colorectal HGNEN cases[13,14]. In line with these prior studies, 63.9% of the cases in our study were rectal HGNEN. More notably, 60.9% of these rectal cases were located in the low rectum. Similar to small cell lung cancer, colorectal HGNEN presented a high degree of malignancy and a high risk of distant metastasis compared to colorectal adenocarcinoma. More than half of the patients had metastatic disease at diagnosis. One investigation based on the Survey of Epidemiology and End Results database analyzed the data from 1367 cases of colorectal HGNEN and 72533 cases of colorectal adenocarcinoma. A significantly higher rate of distant metastases was observed in the HGNEN group (57.9%) than in the adenocarcinoma group (25.2%)[13]. In the present study, 51.4% of the patients presented with distant metastasis at the date of diagnosis. The liver and distant lymph nodes were the most common sites of metastases. There was a trend showing that patients with colonic HGNEN (61.5%) were more likely to develop metastatic disease than those with rectal HGNEN (45.7%). This might be because patients with rectal HGNEN could have rectal bleeding and changes in bowel habits at a relatively early stage, which promoted the early detection of cancer[15]. In contrast to small cell lung cancer, the clinical presentation of colorectal HGNEN is not specific. Carcinoid syndromes can hardly be seen as most of these tumors are nonfunctional and cannot secrete 5-hydroxy-tryptamine[16]. To date, only several cases with hormonal symptoms have been reported in the literature. These patients presented symptoms such as facial flushing, sweating, and diarrhea due to excessive production of hormones[15,17]. In our study, no patients presented with carcinoid syndromes. In most cases, there was no difference in the symptoms or signs between colorectal HGNEN and adenocarcinoma. Hematochezia, abdominal pain, and changes in bowel habits were the most common presentations.

Given the difficulty of distinguishing colorectal HGNEN from adenocarcinoma through clinical manifestation, pathological examination and immunohistochemical evaluation are necessary. In the 2010 WHO classification for gastroenteropancreatic NEN, NENs with a mitotic count greater than 20 per high power field or Ki-67 index greater than 20% are considered poorly differentiated, including small cell and large cell subtypes. Therefore, patients who meet this standard are diagnosed with G3 NEC or HGNEC[18]. However, the histological grade is not always in line with the degree of tumor differentiation[19]. There are some HGNEN cases that show good differentiation, biological behavior similar to that of G2 NETs, and good prognosis. In the 2017 WHO classification for pancreatic NET, well-differentiated G3 pancreatic NENs were categorized as a new subgroup called NET G3, whereas NEC only refers to poorly differentiated G3 pancreatic NENs. Both NET G3 and NEC together were referred to as NEN G3[20,21]. There is a general tendency for this new grading system to be introduced into the classification of colorectal NETs. In the 16th annual ENETS Conference in 2019, Professor Aurel Perren presented “New WHO Classification-Important News”, stating that the terminology of NET G3 is extended to other primary sites, including the colon and rectum. Based on the latest updates on classification and grading of colorectal NENs, all cases in the present study were categorized as well-differentiated subtype (NET G3) and poorly differentiated subtype (NEC) on the basis of histomorphology. However, it was challenging to distinguish NET G3 from NEC based on morphology differentiation alone in many cases. Therefore, genetic status and proliferative activity can be referenced in the updated classification. Cases with mutations of KRAS, BRAF, p53, and Rb1, or with Ki67 index greater than 70%-80% tended to be classified as NEC. A total of 61 cases in our research were confirmed to be NEC. The remaining 11 cases were categorized as NET G3 and constituted 15.3% of all cases, which was higher than previous reports (5.5%-8.7%)[19,22].

Colorectal HGNEN can present characteristic manifestations through immunohistochemical examination. In one retrospective study of 100 colorectal HGNEN cases, synaptophysin was the most sensitive biomarker in the diagnosis of colorectal HGNEN and showed a sensitivity of 93%, which was evidently higher than that of chromogranin (58%) and neuron-specific enolase (87%)[23]. Similarly, synaptophysin demonstrated the highest sensitivity (94%), followed by CD56 (82.4%), neuron-specific enolase (64.3%), and chromogranin (57.6%) in the evaluable cases in our research. Moreover, EMVI was extremely common in colorectal HGNEN and was positive in 76.3% of the evaluable patients. This might help explain the fact that colorectal HGNEN was more prone to distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis.

Due to the rarity of colorectal HGNEN, most published studies are limited to case reports or retrospective studies with small samples. The treatment regimen for this malignancy remains controversial because there is no acknowledged therapeutic schedule. The present treatment regimens are usually extrapolated from evidence on small cell lung cancer and colorectal adenocarcinoma. For patients with localized disease, surgery remains the most common choice in most cases in clinical practice. However, it is still debatable whether patients can benefit from the surgical resection of primary tumors[24,25]. In one retrospective report with 126 colorectal HGNEC patients, surgery did not offer a survival benefit for patients without metastatic disease (median survival, 27.4 mo with surgery vs 20.3 mo without surgery, P = 0.17)[15]. In another retrospective study based on the Survey of Epidemiology and End Results database, the survival outcomes for patients who received surgery differed by histologic subcategory. In the non-small cell group, surgery improved the oncological prognosis (median survival, 21 mo with surgery vs 6 mo without surgery, P < 0.001). In the small cell group, surgery was not associated with superior outcomes (median survival, 18 mo with surgery vs 14 mo without surgery, P = 0.95). This finding is in line with the experience for small-cell lung cancer[13]. In the present study, 34 of 35 (97.1%) patients with localized disease received radical surgery. As only 1 patient did not receive surgery, we could not evaluate the efficacy of surgery. Systemic chemotherapy is regarded as the mainstay for treatment of patients with metastatic disease. Based on the 2010 WHO classification, for all patients with NENs of grade G3, the EP regimen was recommended as the choice for palliative first-line chemotherapy. However, based on the newest classification and grading for NENs G3, the EP regimen was recommended only for patients with NECs, while patients with NETs G3 might benefit from the medical strategy used in NETs G2. Therefore, the TemCap regimen (temozolomide plus capecitabine) is now recommended as a first-line palliative treatment for NETs G3. However, both the retrospective and prospective data related to palliative chemotherapy for NETs G3 were scarce[26]. In the present study, 28 cases received palliative first-line chemotherapy, and the overall response rate was 32.1%. Twelve of 28 (42.9%) patients received 5-FU-based chemotherapy, and 1 (8.3%) patient responded. The remaining 16 (57.1%) patients received platinum-based chemotherapy and showed a response rate of 50%, which is in line with previously reported response rates (ranging from 30% to 50%)[26]. The statistical analysis demonstrated that HGNENs were significantly more sensitive to platinum-based chemotherapy than fluorouracil 5-FU-based chemotherapy (P = 0.039).

Many previous studies of prognosis have delineated poor clinical outcomes of colorectal HGNENs, with a median overall survival (OS) ranging from 9 mo to 20.6 mo, 3-year OS rates ranging from 8.7%-35%, and 5-year OS rates ranging from 8%-13.3%[2,15,17,25,27]. However, most of these reports only enrolled patients with NECs, and survival data for colorectal NETs G3 were scarce. To the best of our knowledge, our study has had the largest sample size enrolling both colorectal NECs and NETs G3 cases to date. As we included many cases with good differentiation, a better prognosis was observed in our cohort, with a median OS of 31 mo and 3-year and 5-year OS rates of 44.3% and 36.3%, respectively. Moreover, unlike previous studies that enrolled some cases diagnosed before 2000, all cases in our study were diagnosed after 2000. The advances in the management of colorectal NENs might contribute to the improved clinical outcomes that were observed in our reports. Both the univariate analysis (P = 0.033) and multivariate analysis (P = 0.005) demonstrated a better prognosis of NETs G3 compared to NECs. For patients with NETs G3, the median OS could not be calculated as over half of the patients survived through the end of follow-up, and the 3-year and 5-year OS rates were 87.5% and 58.3%, respectively. For patients with NECs, the median OS was 25 mo, and the 3-year and 5-year OS rates were 36.4% and 33.1%, respectively. Significant differences in clinical outcomes between NETs G3 and NECs showed that colorectal NETs G3 were less malignant and should not be treated with the same strategies as NECs. Metastatic disease is also an important prognostic factor. In previous reports, 57.9%-67% of patients with colorectal HGNEN presented with distant metastasis at the date of diagnosis[13,15]. However, they accounted for only 51.4% in our study, which might be another reason that our cohort showed a better prognosis than previous studies. These patients had a median OS of only 13 mo, with 3-year and 5-year OS rates of 20.9% and 0, respectively, which was significantly worse than patients without metastatic disease based on both the univariate analysis (P < 0.001) and multivariate analysis (P < 0.001). In addition, we observed a strong trend towards a worse prognosis associated with increasing age. Patients over 70 years old showed a much poorer median survival time (7 mo in patients ≥ 70 vs 47 mo in patients < 70, P < 0.001). This trend was also observed in several prior reports, although the underlying mechanisms have not been well illuminated[13,23]. Elderly patients are usually in poor physical conditions due to their comorbidities, such as diabetes, coronary heart disease, and hepatic and renal dysfunction. This can both decrease their antitumor abilities and constrain the choices of therapy strategies, which subsequently leads to a poor prognosis. Moreover, univariate analyses demonstrated that patients with ulcerative neoplasms, EMVI, and elevated pretreatment blood LDH levels were associated with worse clinical outcomes. However, we did not enroll these factors in the multivariate analysis since these data were not available for all of our cases. Further studies can explore the association between these variables and prognosis so that we can predict survival outcomes through pretreatment examinations.

Our study had several limitations. First, it is a retrospective study, and the bias from patient selection and information collection is unavoidable. Second, the period of our study is within a span of nearly 20 years, the nomenclature and classification of colorectal NETs has been changing, and the early pathological reports are not as normative as they are now. This leads to the lack of vital information, such as the Ki-67 index and pathological type (small cell or large cell), in some patients and makes it difficult to evaluate their value in predicting prognosis.

In conclusion, colorectal HGNENs are rare and heterogeneous groups of malignancies. They present distinct clinicopathologic characteristics with colorectal adenocarcinoma and show a dismal prognosis. Patients with pathologic type NETs G3, younger age, and without distant metastasis might have relatively good clinical outcomes.

Colorectal high-grade neuroendocrine neoplasms (HGNENs) are aggressive malignancies with a dismal prognosis. Due to the rarity of this disease, there are still no related large multicenter prospective randomized studies. Therefore, no standard management recommendations have been established.

Most previous reports are case reports and retrospective studies with small samples from single center of Western countries, and few data from multicenter studies or China can be found. Moreover, there is a trend that colorectal HGNENs will be classified as neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs) and neuroendocrine tumors G3 (NETs G3) based on their morphological differentiation. In prior studies, all colorectal HGNENs were considered NECs.

Based on the latest classification and grading recommendations, we aimed to improve our understanding of this rare disease through multicenter data from China.

We performed an observational study and enrolled patients with colorectal HGNENs from three Chinese hospitals. Information regarding the clinicopathologic features and clinical outcomes was collected and delineated. The prognostic factors were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method and the Cox proportional hazards regression model.

Colorectal HGNENs are highly aggressive, and more than half of the patients have developed distant metastasis at the date of diagnosis. It is difficult to distinguish HGNENs from adenocarcinoma through clinical presentations, and immunohistochemical evaluation is necessary. Survival analysis demonstrated that colorectal NETs G3 had a significantly better prognosis than NECs. Therefore, colorectal HGNENs were not a homogenous group of malignancies, and colorectal NETs G3 should be treated with different strategies from NECs. Moreover, increasing age and distant metastasis were statistically confirmed to be independent risk factors for poor clinical outcomes.

Colorectal HGNENs are aggressive and heterogeneous groups of malignancies. Patients with younger age, good morphological differentiation, and without metastatic disease can have a relatively favorable prognosis.

More large prospective multicenter clinical studies need to be performed so that standard management recommendations can be established. Moreover, colorectal NETs G3 is an emerging term for colorectal HGNENs with good differentiation and that present significantly different biological behavior from NECs. Distinguishing colorectal NETs G3 from NECs is not always easy. It is imperative to further explore their respective molecular mechanisms and genetic changes so that better diagnostic and treatment strategies can be achieved in the future.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Mohamed SY S-Editor: Tang JZ L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Wu Z, Yu D, Zhao S, Gao P, Song Y, Sun Y, Chen X, Wang Z. The efficacy of chemotherapy and operation in patients with colorectal neuroendocrine carcinoma. J Surg Res. 2018;225:54-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bernick PE, Klimstra DS, Shia J, Minsky B, Saltz L, Shi W, Thaler H, Guillem J, Paty P, Cohen AM, Wong WD. Neuroendocrine carcinomas of the colon and rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:163-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 236] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Caplin M, Sundin A, Nillson O, Baum RP, Klose KJ, Kelestimur F, Plöckinger U, Papotti M, Salazar R, Pascher A; Barcelona Consensus Conference participants. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the management of patients with digestive neuroendocrine neoplasms: colorectal neuroendocrine neoplasms. Neuroendocrinology. 2012;95:88-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Garcia-Carbonero R, Sorbye H, Baudin E, Raymond E, Wiedenmann B, Niederle B, Sedlackova E, Toumpanakis C, Anlauf M, Cwikla JB, Caplin M, O'Toole D, Perren A; Vienna Consensus Conference participants. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for High-Grade Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors and Neuroendocrine Carcinomas. Neuroendocrinology. 2016;103:186-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 382] [Cited by in RCA: 419] [Article Influence: 46.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Vélayoudom-Céphise FL, Duvillard P, Foucan L, Hadoux J, Chougnet CN, Leboulleux S, Malka D, Guigay J, Goere D, Debaere T, Caramella C, Schlumberger M, Planchard D, Elias D, Ducreux M, Scoazec JY, Baudin E. Are G3 ENETS neuroendocrine neoplasms heterogeneous? Endocr Relat Cancer. 2013;20:649-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 236] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sorbye H, Baudin E, Borbath I, Caplin M, Chen J, Cwikla JB, Frilling A, Grossman A, Kaltsas G, Scarpa A, Welin S, Garcia-Carbonero R; ENETS 2016 Munich Advisory Board Participants. Unmet Needs in High-Grade Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms (WHO G3). Neuroendocrinology. 2019;108:54-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Koenig A, Krug S, Mueller D, Barth PJ, Koenig U, Scharf M, Ellenrieder V, Michl P, Moll R, Homayunfar K, Kann PH, Stroebel P, Gress TM, Rinke A. Clinicopathological hallmarks and biomarkers of colorectal neuroendocrine neoplasms. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0188876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Starzyńska T, Londzin-Olesik M, Bałdys-Waligórska A, Bednarczuk T, Blicharz-Dorniak J, Bolanowski M, Boratyn-Nowicka A, Borowska M, Cichocki A, Ćwikła JB, Deptała A, Falconi M, Foltyn W, Handkiewicz-Junak D, Hubalewska-Dydejczyk A, Jarząb B, Junik R, Kajdaniuk D, Kamiński G, Kolasińska-Ćwikła A, Kowalska A, Król R, Królicki L, Kunikowska J, Kuśnierz K, Lampe P, Lange D, Lewczuk-Myślicka A, Lewiński A, Lipiński M, Marek B, Nasierowska-Guttmejer A, Nowakowska-Duława E, Pilch-Kowalczyk J, Remiszewski P, Rosiek V, Ruchała M, Siemińska L, Sowa-Staszczak A, Steinhof-Radwańska K, Strzelczyk J, Sworczak K, Syrenicz A, Szawłowski A, Szczepkowski M, Wachuła E, Zajęcki W, Zemczak A, Zgliczyński W, Kos-Kudła B. Colorectal neuroendocrine neoplasms - management guidelines (recommended by the Polish Network of Neuroendocrine Tumours). Endokrynol Pol. 2017;68:250-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Basuroy R, Haji A, Ramage JK, Quaglia A, Srirajaskanthan R. Review article: the investigation and management of rectal neuroendocrine tumours. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:332-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Chablaney S, Zator ZA, Kumta NA. Diagnosis and Management of Rectal Neuroendocrine Tumors. Clin Endosc. 2017;50:530-536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kyriakopoulos G, Mavroeidi V, Chatzellis E, Kaltsas GA, Alexandraki KI. Histopathological, immunohistochemical, genetic and molecular markers of neuroendocrine neoplasms. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6:252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kang H, O'Connell JB, Leonardi MJ, Maggard MA, McGory ML, Ko CY. Rare tumors of the colon and rectum: a national review. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:183-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Shafqat H, Ali S, Salhab M, Olszewski AJ. Survival of patients with neuroendocrine carcinoma of the colon and rectum: a population-based analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:294-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Aytac E, Ozdemir Y, Ozuner G. Long term outcomes of neuroendocrine carcinomas (high-grade neuroendocrine tumors) of the colon, rectum, and anal canal. J Visc Surg. 2014;151:3-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Smith JD, Reidy DL, Goodman KA, Shia J, Nash GM. A retrospective review of 126 high-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas of the colon and rectum. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:2956-2962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Anthony LB, Strosberg JR, Klimstra DS, Maples WJ, O'Dorisio TM, Warner RR, Wiseman GA, Benson AB, Pommier RF; North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (NANETS). The NANETS consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors (nets): well-differentiated nets of the distal colon and rectum. Pancreas. 2010;39:767-774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kim ST, Ha SY, Lee J, Hong SN, Chang DK, Kim YH, Park YA, Huh JW, Cho YB, Yun SH, Lee WY, Kim HC, Park YS. The Clinicopathologic Features and Treatment of 607 Hindgut Neuroendocrine Tumor (NET) Patients at a Single Institution. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e3534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cives M, Strosberg JR. Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:471-487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 271] [Cited by in RCA: 404] [Article Influence: 57.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Milione M, Maisonneuve P, Spada F, Pellegrinelli A, Spaggiari P, Albarello L, Pisa E, Barberis M, Vanoli A, Buzzoni R, Pusceddu S, Concas L, Sessa F, Solcia E, Capella C, Fazio N, La Rosa S. The Clinicopathologic Heterogeneity of Grade 3 Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Morphological Differentiation and Proliferation Identify Different Prognostic Categories. Neuroendocrinology. 2017;104:85-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kim JY, Hong SM, Ro JY. Recent updates on grading and classification of neuroendocrine tumors. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2017;29:11-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Guilmette JM, Nosé V. Neoplasms of the Neuroendocrine Pancreas: An Update in the Classification, Definition, and Molecular Genetic Advances. Adv Anat Pathol. 2019;26:13-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Heetfeld M, Chougnet CN, Olsen IH, Rinke A, Borbath I, Crespo G, Barriuso J, Pavel M, O'Toole D, Walter T; other Knowledge Network members. Characteristics and treatment of patients with G3 gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2015;22:657-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 289] [Article Influence: 28.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Conte B, George B, Overman M, Estrella J, Jiang ZQ, Mehrvarz Sarshekeh A, Ferrarotto R, Hoff PM, Rashid A, Yao JC, Kopetz S, Dasari A. High-Grade Neuroendocrine Colorectal Carcinomas: A Retrospective Study of 100 Patients. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2016;15:e1-e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Brieau B, Lepère C, Walter T, Lecomte T, Guimbaud R, Manfredi S, Tougeron D, Desseigne F, Lourenco N, Afchain P, El Hajbi F, Terris B, Rougier P, Coriat R. Radiochemotherapy Versus Surgery in Nonmetastatic Anorectal Neuroendocrine Carcinoma: A Multicenter Study by the Association des Gastro-Entérologues Oncologues. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e1864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Fields AC, Lu P, Vierra BM, Hu F, Irani J, Bleday R, Goldberg JE, Nash GM, Melnitchouk N. Survival in Patients with High-Grade Colorectal Neuroendocrine Carcinomas: The Role of Surgery and Chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26:1127-1133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sorbye H, Baudin E, Perren A. The Problem of High-Grade Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Well-Differentiated Neuroendocrine Tumors, Neuroendocrine Carcinomas, and Beyond. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2018;47:683-698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Voong KR, Rashid A, Crane CH, Minsky BD, Krishnan S, Yao JC, Wolff RA, Skibber JM, Feig BW, Chang GJ, Das P. Chemoradiation for High-grade Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of the Rectum and Anal Canal. Am J Clin Oncol. 2017;40:555-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |