Published online Sep 14, 2019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i34.5174

Peer-review started: April 8, 2019

First decision: May 24, 2019

Revised: June 15, 2019

Accepted: June 25, 2019

Article in press: June 26, 2019

Published online: September 14, 2019

Processing time: 159 Days and 17.3 Hours

Adverse events during endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) of superficial esophageal neoplasms, such as perforation and bleeding, have been well-documented. However, the Mallory-Weiss Tear (MWT) during esophageal ESD remains under investigation.

To investigate the incidence and risk factors of the MWT during esophageal ESD.

From June 2014 to July 2017, patients with superficial esophageal neoplasms who received ESD in our institution were retrospectively analyzed. The clinicopathological characteristics of the patients were collected. Patients were divided into an MWT group and non-MWT group based on whether MWT occurred during ESD. The incidence of MWTs was determined, and the risk factors for MWT were then further explored.

A total of 337 patients with 373 lesions treated by ESD were analyzed. Twenty patients developed MWTs during ESD (5.4%). Multivariate analysis identified that female sex (OR = 5.36, 95%CI: 1.47-19.50, P = 0.011) and procedure time longer than 88.5 min (OR = 3.953, 95%CI: 1.497-10.417, P = 0.005) were independent risk factors for an MWT during ESD. The cutoff value of the procedure time for an MWT was 88.5 min (sensitivity, 65.0%; specificity, 70.8%). Seven of the MWT patients received endoscopic hemostasis. All patients recovered satisfactorily without surgery for the laceration.

The incidence of MWTs during esophageal ESD was much higher than expected. Although most cases have a benign course, fatal conditions may occur. We recommend inspection of the stomach during and after the ESD procedure for timely management in cases of bleeding MWTs or even perforation outside of the procedure region.

Core tip: To our knowledge, no literature has focused on the risk factors for an Mallory-Weiss Tear (MWT) during esophageal endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). Thus, the present study aimed to clarify the incidence of WMTs during esophageal ESD, and to evaluate associated risk factors. In this work, we found that female sex and procedure time were independent risk factors for an MWT during ESD. For patients with such characteristics, clinicians must remain vigilant and perform careful observations after ESD.

- Citation: Chen W, Zhu XN, Wang J, Zhu LL, Gan T, Yang JL. Risk factors for Mallory-Weiss Tear during endoscopic submucosal dissection of superficial esophageal neoplasms. World J Gastroenterol 2019; 25(34): 5174-5184

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v25/i34/5174.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i34.5174

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) has been widely accepted as an effective treatment for superficial esophageal neoplasms when the risk of lymph node metastasis is diagnosed as being very low or negligible[1-3]. Adverse events, such as bleeding, muscularis propria injury, and even perforation during the procedure are well-documented by endoscopists, and can mostly be managed endoscopically[3-5]. However, the Mallory-Weiss Tear (MWT) during ESD is not well-understood.

The MWT, first described in 1929, is characterized by a linear, non-perforation mucosal laceration at the gastroesophageal junction that is induced by vomiting and retching[6]. Previous studies have reported that the classical MWT (non-iatrogenic MWT) accounted for 7%-14% of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding, including even cirrhotic patients[7-10]. The first documented case of an MWT resulting from endoscopy was reported by Watts in 1976[11], and the incidence was reported to be 0.08%-0.49%[12-15]. Associated risk factors for an MWT during screening endoscopy include hiatal hernia, female sex, a history of distal gastrectomy and old age[14-16]. With the development of endoscopic technology and growing emphasis on the diagnosis and endoscopic treatment of early esophageal cancer, ESD-associated MWT is reported case by case. However, to our knowledge, no literature has focused on the risk factors for an MWT during esophageal ESD. Thus, the present study aimed to clarify the incidence of WMTs during esophageal ESD, and to evaluate the associated risk factors.

From June 2014 to July 2017, 341 consecutive patients with 377 superficial esophageal neoplasms were treated by ESD at the West China Hospital of Sichuan University. The indication criteria of ESD for superficial esophageal neoplasms were: (1) Intraepithelial neoplasia or carcinoma determined by biopsy, performed during chromoendoscopy with iodine staining; (2) Depth of invasion limited to within sm1, as assessed by endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) and/or magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging (ME-NBI); and (3) The absence of lymph node or distant metastasis confirmed by contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the chest and abdomen. Patients with a history of esophagectomy, proximal gastrectomy or total gastrectomy were excluded from this study. Additionally, all patients completed diagnostic endoscopies before treatment without an MWT occurring. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before the procedures. The present study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the West China Hospital of Sichuan University.

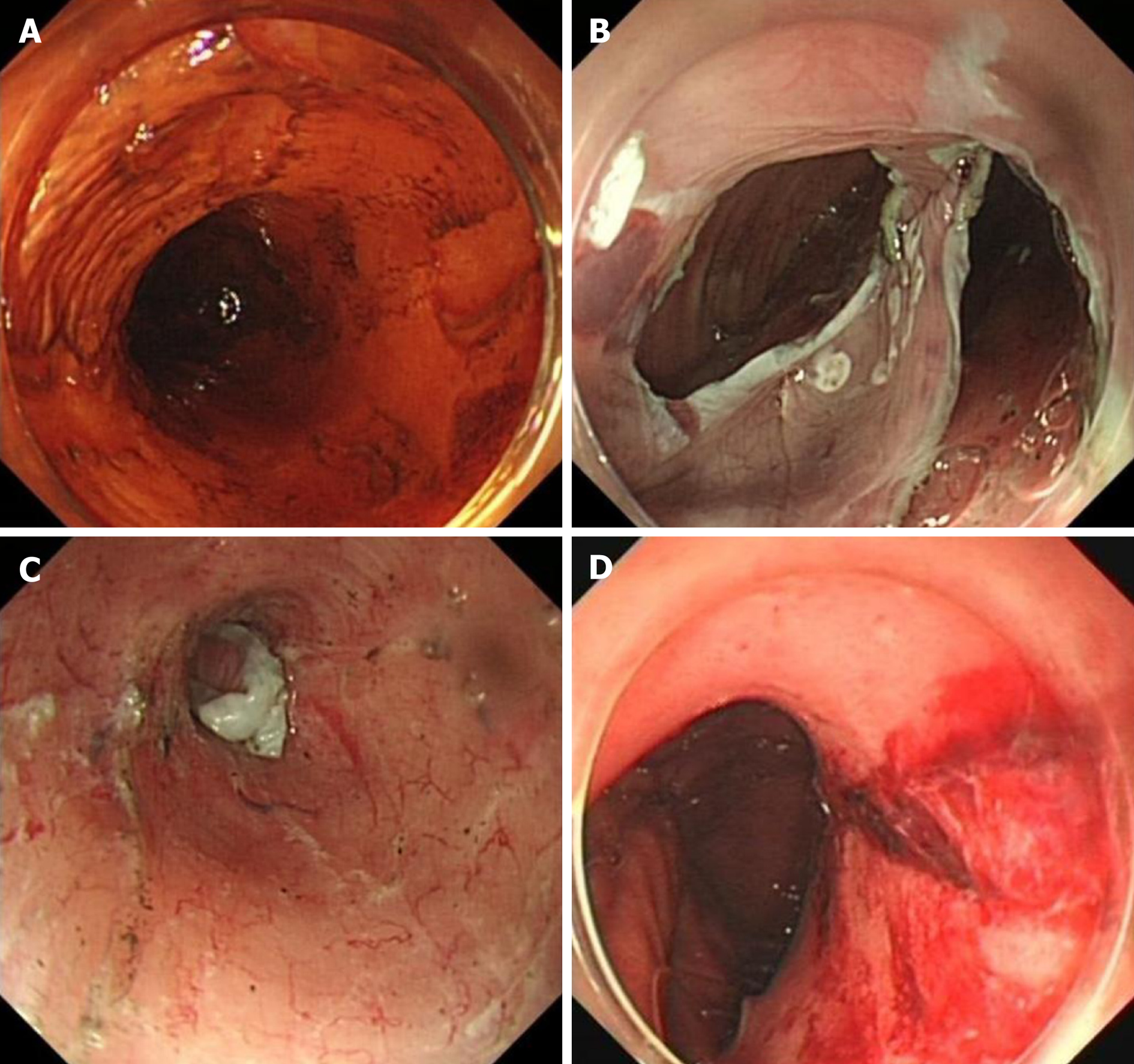

The ESD procedure was categorized as conventional ESD and endoscopic submucosal tunnel dissection (ESTD) (Figure 1). The conventional ESD procedure comprised four steps: (1) Marking the margin of the lesion; (2) Submucosal injection to elevate the lesion; (3) Mucosal incision around the lesion; and (4) Submucosal dissection. Regarding ESTD, one or more submucosal tunnels were established during the dissection step. The ESD procedure was decided by the endoscopist according to the size of the lesion.

ESD was performed with a single-accessory channel endoscope (GIF-Q260J, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with a transparent cap (D-201-10704, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) attached to the front. Other equipment and accessories included: A high-frequency generator (VIO200D; ERBE ELEKTROMEDIZIN GMBH, Germany), argon plasma coagulation (APC) unit (APC-ICC200; ERBE ELEKTROMEDIZIN GMBH, Germany), IT knife (KD -611L, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), Dual-knife (KD-650L/Q, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), injection needle (NM-200U-0423, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), and hemostatic forceps (FD-410 LR, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

All patients were under mechanically-ventilated general anesthesia, and in the supine position. ESD was performed by one experienced endoscopist (with 25 years of endoscopy experience and > 300 cases of esophageal ESD) and two less-experienced endoscopists (with 15 years of endoscopy experience and approximately 100 cases of esophageal ESD), and carbon dioxide was used for insufflation. After resection of the esophageal lesion, the gastrointestinal decompression tube was placed, and proton-pump inhibitors (PPI) and hemostatic drugs were used on all patients. Endoscopic follow up was scheduled at 1, 3, 6, and 12 mo after ESD, and then annually.

The decisions regarding the treatment strategy, including whether to treat the MWT endoscopically, were made by endoscopists according to the size of the laceration and the presence of active bleeding. Based on the endoscopic findings, APC, hemoclips or hemoclips combined with endoloop were used to treat the MWT.

MWT was defined as a mucosal tear at the esophagastric junction with or without active bleeding during the ESD procedure. Atrophic gastritis and hiatal hernia were diagnosed based on endoscopic findings. The longitudinal diameter of the esophageal lesion was measured from the oral edge to the anal edge of the resected specimens, and the circumferential diameter was determined based on the length of the vertical axis against the longitudinal axis. The circumferential extent of the mucosal defect was judged by the endoscopists. Curative resection was defined as en bloc resection with tumor-free horizontal and vertical margins, and met the following conditions simultaneously: Invasion depth limited in the submucosa < 200 μm without lymphovascular involvement.

Data pertaining to potential predisposing factors, such as age, sex, atrophic gastritis, hiatal hernia, characteristics of the esophageal lesions, and the experience of the endoscopists were collected from our prospectively maintained endoscopic database.

Variables are reported using the median (range) and simple proportion according to the type of data. The Mann-Whitney U test, chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test were used for univariate analysis, as appropriate. Clinically or statistically significant variables in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate logistic regression analysis to assess the independent risk factors for an MWT. Differences with a P < 0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 23 for Windows.

A total of 341 patients with 377 superficial esophageal neoplasms were treated by ESD from June 2014 to July 2017 in our institution. Four patients with four lesions were excluded because of a history of esophagectomy, proximal gastrectomy or total gastrectomy. The remaining 337 patients with 373 lesions were reviewed for the present study. During the period of study, 20 (5.4%) MWT cases developed during the ESD procedure.

The clinicopathological features of the patents and lesions are shown in Table 1. Overall, the median age of the patients was 62 years (range, 37-83 years), and the male proportion was 67.7%. Of the 373 lesions, 67.6% (252/373) were located in the middle esophagus, and 26.8% (100/373) were located in the lower esophagus. The median circumferential and longitudinal diameters of the specimen were 2.5 cm (range, 0.5-7.0 cm) and 4.0 cm (range, 1.0-14.0 cm), respectively. The median procedure time was 60 min (range, 12-240 min). The en bloc resection rate and curative resection rate were achieved in 96.2% (359/373) and 86.1% (321/373) of the lesions, respectively. The histology and invasion depth were as follows: Intraepithelial neoplasia, 131 (35.1%); mucosal invasion, 194 (52.0%); SM < 200 μm invasion, 21 (5.6%); and SM ≥ 200 μm invasion 26 (7.0%). Perforations developed in 6 (1.6%) cases, and the incidence of stenosis was 12.3% (46/373).

| Characteristics | n (%)/median (range) |

| No. of patients | 337 |

| Age in yr | 62 (37-83) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 228 (67.7) |

| Female | 109 (32.3) |

| Concomitant diseases | |

| Atrophic gastritis | 15 (4.4) |

| Hiatal hernia | 2 (0.6) |

| History of distal gastrectomy | 4 (1.2) |

| No. of lesions | 373 |

| Location | |

| Upper | 21 (5.6) |

| Middle | 252 (67.6) |

| Lower | 100 (26.8) |

| Longitudinal diameter of specimen in cm | 4.0 (1.0-14.0) |

| Circumferential diameter of specimen in cm | 2.5 (0.5-7.0) |

| Size of specimen in cm2 | 9.8 (0.5-70.0) |

| Circumferential extent of the mucosal defect | |

| < 75% | 268 (71.8) |

| ≥ 75% | 105 (28.2) |

| Histology and depth of invasion | |

| Intraepithelial neoplasia | 131 (35.1) |

| Mucosa | 195 (52.3) |

| Sub-mucosa < 200 μm | 21 (5.6) |

| Sub-mucosa ≥ 200 μm | 26 (7.0) |

| Procedure time in min | 60 (12-240) |

| En bloc resection | 359 (96.2) |

| Curative resection | 321 (86.1) |

| Type of ESD procedure | |

| Conventional ESD | 33 (8.8) |

| ESTD | 340 (91.2) |

| Endoscopists | |

| Experienced | 224 (60.1) |

| Less-experienced | 149 (39.9) |

| Adverse events | |

| MWT | 20 (5.4) |

| Perforation | 6 (1.6) |

| Stenosis | 46 (12.3) |

Twenty patients developed MWTs during the ESD procedure. The characteristics of the patients with or without MWTs are shown in Table 2. Predisposing factors[14,16] including atrophic gastritis, hiatal hernia, and a history of distal gastrectomy were not observed in the MWT cases. There was no significant difference in age, concomitant diseases, location, size, invasion depth, type of resection, or experience of the endoscopists between the two groups. However, in the MWT group, the proportion of female patients was much higher (70.0% vs 30.0%, P < 0.001), and the procedure time was longer (90 vs 58 min, P = 0.008) than the non-MWT group. Multivariate logistic regression analysis (Table 3) revealed that female sex was an independent risk factor for an MWT during esophageal endoscopic resection (OR = 5.27, 95%CI: 1.94-14.32, P = 0.001), and the procedure time longer than 88.5 mins was also an independent risk factor for an MWT during esophageal endoscopic resection (OR = 3.953, 95%CI: 1.497-10.417, P = 0.005). The association between MWT and procedure time was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, and the cutoff value of the procedure time was 88.5 min (sensitivity, 65.0%; specificity, 70.8%), as calculated by the Youden index method. This result suggested that female patients with procedure times longer than 88.5 min were susceptible to MWTs during esophageal endoscopic resection.

| MWT | Non-MWT | P value | |

| No. of patients | 20 | 317 | |

| Age in yr, median (range) | 65 (47-77) | 62 (37-83) | 0.065 |

| Sex as male/female | 6/14 | 222/95 | a0.001 |

| Concomitant disease, n | |||

| Atrophic gastritis | 0 | 15 | 1.000 |

| Hiatal hernia | 0 | 2 | 1.000 |

| History of distal gastrectomy | 0 | 4 | 1.000 |

| No. of lesions | 20 | 353 | |

| Location of the center | 0.566 | ||

| Upper | 2 (10.0) | 19 (5.4) | |

| Middle | 13 (65.0) | 239 (67.7) | |

| Lower | 5 (25.0) | 95 (26.9) | |

| Longitudinal diameter in cm, median (range) | 5 (2-8) | 4 (1-14) | 0.125 |

| Circumferential diameter in cm, median (range) | 2.75 (1-5) | 2.5 (0.5-7) | 0.591 |

| Size of specimen in cm2, median (range) | 11.25 (2-32.5) | 9.6 (0.5-70) | 0.312 |

| Circumferential extent of the mucosal defect | 0.085 | ||

| < 75% | 11 (55) | 257 (72.8) | |

| ≥ 75% | 9 (45) | 96 (27.2) | |

| Depth of invasion | 0.377 | ||

| Intraepithelial neoplasia | 4 (20) | 127 (36.0) | |

| Mucosa | 13 (65) | 182 (51.6) | |

| Submucosa < 200 μm | 1 (5) | 20 (5.7) | |

| Submucosa ≥ 200 μm | 2 (10) | 24 (6.8) | |

| Submucosal adhesion, n | 3 (15) | 36 (10.2) | 0.452 |

| Procedure time in min, median (range) | 90 (28-180) | 58 (12-240) | a0.008 |

| Type of resection | 0.694 | ||

| Conventional ESD | 2 (10) | 31 (8.8) | |

| ESTD | 18 (90) | 322 (91.2) | |

| Operators | 0.635 | ||

| Experienced | 11(55) | 213 (60.3) | |

| Less-experienced | 9 (45) | 140 (39.7) | |

Among the 20 patients with MWTs, 6 received endoscopic treatment for the laceration during the ESD procedure. Five patients with slight oozing were treated by APC or endoclips. One patient was treated with 9 endoclips and 1 endoloop to close the laceration, as the mucosal tear was deep and long, with visible vessel and errhysis. The remaining patients did not receive endoscopic hemostasis, and had a benign clinical course, with the exception of one patient (case 7, Table 4) who received a blood transfusion and emergency endoscopy due to delayed bleeding. In this patient, the laceration was not serious at the end of the ESD procedure. However, nausea and vomiting after ESD might have aggravated the laceration, and resulted in hematemesis. In the emergency endoscopy, longitudinal laceration was observed at the esophagastric junction, with visible vessel and blood oozing. After a sprinkle of epinephrine solution (1:10000) and APC, the active bleeding stopped.

| Patients | Age in yr | Sex | Location | Circumfe-rential of mucosal defect | Procedure time in min | Expert | Endoscopic treatment of MWT | Invasion depth | Submucosal adhesion |

| Case 1 | 72 | F | M | 3/5 | 60 | Y | - | Tis | N |

| Case 2 | 61 | M | L | 3/4 | 69 | Y | - | Tis | N |

| Case 3 | 63 | F | M | 1/2 | 28 | Y | - | Tis | N |

| Case 4 | 47 | M | L | 1/3 | 45 | Y | - | LGIN | N |

| Case 5 | 65 | F | M | 3/4 | 90 | N | - | HGIN | N |

| Case 6 | 64 | F | M | 4/5 | 98 | Y | - | M2 | Y |

| Case 7 | 51 | F | M | 4/5 | 121 | Y | E & APC1 | M2 | N |

| Case 8 | 66 | F | M | 2/3 | 125 | N | - | Tis | N |

| Case 9 | 64 | F | M | 4/5 | 175 | N | - | Tis | N |

| Case 10 | 77 | M | L | 1 | 180 | N | APC | SM, 550 μm | N |

| Case 11 | 60 | F | M | 1/4 | 45 | N | - | LGIN | N |

| Case 12 | 67 | F | M | 2/3 | 100 | N | APC | SM, 100 μm | N |

| Case 13 | 67 | M | L | 1/2 | 90 | N | - | M3 | N |

| Case 14 | 57 | M | M | 5/6 | 155 | N | APC | M2 | N |

| Case 15 | 69 | F | M | 1/2 | 57 | Y | Clips | HGIN | Y |

| Case 16 | 66 | F | M | 1/2 | 40 | Y | Clips | Tis | Y |

| Case 17 | 67 | M | L | 1 | 105 | Y | Clips and loop | M2 | N |

| Case 18 | 65 | F | M | 2/3 | 89 | Y | - | M2 | N |

| Case 19 | 64 | F | U | 1 | 150 | Y | - | M2 | N |

| Case 20 | 67 | F | U | 2/3 | 90 | N | - | SM, 220 μm | N |

Additionally, a severe gas-related adverse event, namely, gastric perforation, occurred in one patient (patient 9, Table 4). The perforation was closed endoscopically by hemoclips and endoloops using a double purse-string suture. As the MWT of the patient was relatively slight without active bleeding, no endoscopic treatment was performed.

In general, most of the patients had a benign clinical course, and no surgery was required for the MWT.

This study suggested that the incidence of MWTs during esophageal ESD was 5.4%. Okada et al[13] reported a lower incidence of 2.59% (11/424) of MWTs during upper gastrointestinal ESD. However, the authors did not analyze the morbidity separately based on the procedure site.

The incidence of MWTs during screening endoscopy is reported to be 0.08%-0.49%[12-15], which is much lower than that of ESD-associated MWTs. We suggest that the longer procedure time, with gas insufflation and the invasive operation, may somehow contribute to the high incidence of MWTs. Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) is another treatment method for superficial esophageal neoplasms, especially for small lesions, which have simpler procedure steps with significantly shorter procedure times than ESD. A study[13] identified only one MWT in all 303 patients of esophageal EMR, suggesting a similar incidence to that of diagnostic endoscopy, which indicated that the procedure time was closely associated with the MWT. Accordingly, in our study, univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses showed that the procedure time was an independent risk factor for an MWT during esophageal ESD.

The development of an endoscopic-associated MWT is closely associated with gas insufflation. An RCT reported that the incidence of MWTs was significantly lower with CO2 insufflation than with air insufflation (0% vs 15.6%) during gastric ESD, because CO2 can be rapidly absorbed compared to air. However, as the sample size of this study was small, the incidence of MWTs was of low reliability. A Japanese study reported that the incidence of MWTs during gastric ESD is 3.4%, which is lower than that of our study of esophageal ESD. We presume that the direct insight of the stomach is favorable for the supervision of the inflation status of the stomach cavity, and is convenient for gas suction during the ESD procedure.

Predisposing conditions for non-iatrogenic MWTs include chronic alcoholism, the presence of hiatal hernia and atrophic gastritis. Most cases occur after the precipitating factors of fierce vomiting, retching, straining at defecation and coughing[10,17-20]. Scarce reports have suggested associated risk factors for MWTs during screening endoscopy, such as the presence of hiatal hernia, female sex, and a history of distal gastrectomy and old age, while retching or struggling during the procedure remains in dispute[14-16]. In the present study, multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that female sex was an independent risk factor for an MWT. We presumed that the strength of the abdominal muscle in female patients was much weaker than that in male patients. Therefore, the gastric wall could not help to withstand the increasing intragastric pressure caused by the insufflation of gas. This viewpoint could be supported by Kawano et al’s[21] study that a low body mass index (< 18.5) is a risk factor for MWT during gastric ESD. Features of the esophageal lesions had no influence on the development of MWTs. Moreover, neither endoscopic findings of atrophic gastritis nor hiatal hernia were found in the 20 MWT patients. This was in accordance with a case-control study showing that hiatal hernia was not associated with MWT[22].

In general, the majority of patients with MWTs have a benign clinical course, and most can be treated conservatively, even without endoscopic intervention[13,15]. Nevertheless, a complicated course, including blood transfusion, rebleeding, surgery and even death, can also occur in 6%-23% of patients when advanced age, active bleeding at initial endoscopy, a lower admission hemoglobin level, clinical symptoms of tarry stool, longer lacerations, and underlying comorbidities are present[13,18,23-26]. In our study, the vast majority of patients did not receive endoscopic treatment, and recovered satisfactorily. We suggest that the placement of a gastrointestinal decompression tube, as well as the use of PPIs and hemostatic drugs after ESD, contributed to hemostasis and mucosal healing. However, only one patient with an MWT who did not receive endoscopic intervention suffered delayed bleeding, and required blood transfusion and emergency endoscopy for hemostasis due to nausea and vomiting after ESD. Six patients with MWTs were treated by endoscopic hemostasis using APC, hemoclips, or hemoclips combined with endoloop during the ESD procedure. Generally, the clinical course and outcome of MWTs during ESD were better than those of classical MWTs. Because post-ESD management was favorable for hemostasis and wound healing, the laceration could be found promptly after the ESD procedure, and could be managed in a timely manner depending on the endoscopic findings. Therefore, it is of great importance to detect the MWT during ESD, and to take optimal endoscopic intervention measures when active bleeding is present.

Endoscopic hemostasis methods for MWT bleeding, including hemoclips, band ligation, epinephrine injection, and electrocoagulation, can achieve a high primary hemostasis rate of more than 90% with a low rebleeding rate and few com-plications[27-31]. Mechanical methods such as hemoclips and band ligation were superior to epinephrine injection to some extent[28-30].

Although MWT bleeding is mild and can mostly stop spontaneously without endoscopic hemostasis, the spectrum of MWTs is wide and sometimes may result in a fatal condition. Therefore, we recommend an inspection of the esophagastric junction and stomach after the whole procedure of the esophagus to ensure the soundness of the mucosa out of the procedure region. Moreover, inspection during the procedure with gas suction is also proposed when the ESD procedure time is long, especially in female patients. It may help to prevent MWT and avoid further overflow of gas, which may cause further injury. This is essential for the prevention of massive hemorrhage, and even perforation caused by a delayed diagnosis, to avoid unnecessary panic and even surgery or death. In addition, a pressure monitoring system may be useful for the prevention of MWT[32,33].

There are several limitations in the present study. This was a retrospective study from a single center, which may lead to selection bias and a lack of representation. Although the number of MWT cases was large compared with that of other studies, the sample size was still small, as the incidence rate was low. Therefore, further investigations with large sample sizes will be needed.

This is the first study to identify the incidence of MWTs during esophageal ESD, and to analyze the associated risk factors. In conclusion, our study demonstrated that the incidence of MWTs during ESD of superficial esophageal neoplasms is 5.4%. Female sex and a long procedure time (> 88.5 min) are independent risk factors for an MWT. Although all MWT cases recovered satisfactorily, we suggest confirmation of the mucosa out of the procedure region after ESD for the timely diagnosis and management of MWTs.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) has been widely accepted as an effective treatment for superficial esophageal neoplasms when the risk of lymph node metastasis is diagnosed as being very low or negligible. With the development of endoscopic technology and growing emphasis on the diagnosis and endoscopic treatment of early esophageal cancer, the ESD-associated Mallory-Weiss Tear (MWT) is reported case by case.

Adverse events during ESD of superficial esophageal neoplasms, such as perforation and bleeding, have been well-documented. However, MWT during esophageal ESD remains under investigation. The present study was carried out to investigate the incidence and risk factors of MWT during esophageal ESD, since no literature has focused on the risk factors for an MWT during esophageal ESD.

The present study aimed to clarify the incidence of WMTs during esophageal ESD, and to evaluate the associated risk factors.

Patients with superficial esophageal neoplasms who received ESD in our institution were retrospectively analyzed. The clinicopathological characteristics of the patients were collected. Patients were divided into a MWT group and non-MWT group based on whether MWT occurred during ESD. The incidence of MWTs was determined, and the risk factors for an MWT were then further explored.

Twenty patients developed MWTs during ESD (5.4%). Multivariate analysis identified that female sex (OR = 5.36, 95%CI: 1.47-19.50, P = 0.011) and procedure time longer than 88.5 min (OR = 3.953, 95%CI: 1.497-10.417, P = 0.005) were independent risk factors for an MWT during ESD. The cutoff value of the procedure time for an MWT was 88.5 min (sensitivity, 65.0%; specificity, 70.8%).

The incidence of MWTs during esophageal ESD was much higher than expected. Although most cases have a benign course, fatal conditions may occur. We recommend inspection of the stomach during and after the ESD procedure for timely management in cases of bleeding MWTs or even perforation outside of the procedure region.

The present study aimed to clarify the incidence of WMTs during esophageal ESD, and to evaluate associated risk factors. In this work, we found that female sex and procedure time were independent risk factors for an MWT during ESD. For patients with such characteristics, clinicians must remain vigilant and perform careful observations after ESD.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Hashimoto R, Ono T S-Editor: Ma RY L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Pimentel-Nunes P, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Ponchon T, Repici A, Vieth M, De Ceglie A, Amato A, Berr F, Bhandari P, Bialek A, Conio M, Haringsma J, Langner C, Meisner S, Messmann H, Morino M, Neuhaus H, Piessevaux H, Rugge M, Saunders BP, Robaszkiewicz M, Seewald S, Kashin S, Dumonceau JM, Hassan C, Deprez PH. Endoscopic submucosal dissection: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2015;47:829-854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 817] [Cited by in RCA: 927] [Article Influence: 92.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Choi JY, Park YS, Jung HY, Ahn JY, Kim MY, Lee JH, Choi KS, Kim DH, Choi KD, Song HJ, Lee GH, Cho KJ, Kim JH. Feasibility of endoscopic resection in superficial esophageal squamous carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:881-889, 889.e1-889.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tsujii Y, Nishida T, Nishiyama O, Yamamoto K, Kawai N, Yamaguchi S, Yamada T, Yoshio T, Kitamura S, Nakamura T, Nishihara A, Ogiyama H, Nakahara M, Komori M, Kato M, Hayashi Y, Shinzaki S, Iijima H, Michida T, Tsujii M, Takehara T. Clinical outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial esophageal neoplasms: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Endoscopy. 2015;47:775-783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Takahashi R, Yoshio T, Horiuchi Y, Omae M, Ishiyama A, Hirasawa T, Yamamoto Y, Tsuchida T, Fujisaki J. Endoscopic tissue shielding for esophageal perforation caused by endoscopic resection. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2017;10:214-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Libânio D, Pimentel-Nunes P, Dinis-Ribeiro M. Complications of endoscopic resection techniques for upper GI tract lesions. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;30:735-748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mallory GK, Weiss S. Hemorrhages from lacerations of the cardiac orifice of the stomach due to vomiting. Am J Med Sci. 1929;178:506-514. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lecleire S, Di Fiore F, Merle V, Hervé S, Duhamel C, Rudelli A, Nousbaum JB, Amouretti M, Dupas JL, Gouerou H, Czernichow P, Lerebours E. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with liver cirrhosis and in noncirrhotic patients: epidemiology and predictive factors of mortality in a prospective multicenter population-based study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:321-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Halland M, Young M, Fitzgerald MN, Inder K, Duggan JM, Duggan A. Characteristics and outcomes of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage in a tertiary referral hospital. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:3430-3435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Saylor JL, Tedesco FJ. Mallory-Weiss syndrome in perspective. Am J Dig Dis. 1975;20:1131-1134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Knauer CM. Mallory-Weiss syndrome. Characterization of 75 Mallory-weiss lacerations in 528 patients with upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Gastroenterology. 1976;71:5-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Watts HD. Mallory-Weiss syndrome occurring as a complication of endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1976;22:171-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Shimoda R, Iwakiri R, Sakata H, Ogata S, Ootani H, Sakata Y, Fujise T, Yamaguchi K, Mannen K, Arima S, Shiraishi R, Noda T, Ono A, Tsunada S, Fujimoto K. Endoscopic hemostasis with metallic hemoclips for iatrogenic Mallory-Weiss tear caused by endoscopic examination. Dig Endosc. 2009;21:20-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Okada M, Ishimura N, Shimura S, Mikami H, Okimoto E, Aimi M, Uno G, Oshima N, Yuki T, Ishihara S, Kinoshita Y. Circumferential distribution and location of Mallory-Weiss tears: recent trends. Endosc Int Open. 2015;3:E418-E424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Na S, Ahn JY, Jung KW, Lee JH, Kim DH, Choi KD, Song HJ, Lee GH, Jung HY, Han S. Risk Factors for an Iatrogenic Mallory-Weiss Tear Requiring Bleeding Control during a Screening Upper Endoscopy. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2017;2017:5454791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Montalvo RD, Lee M. Retrospective analysis of iatrogenic Mallory-Weiss tears occurring during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Hepatogastroenterology. 1996;43:174-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Penston JG, Boyd EJ, Wormsley KG. Mallory-Weiss tears occurring during endoscopy: a report of seven cases. Endoscopy. 1992;24:262-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Dagradi AE, Broderick JT, Juler G, Wolinsky S, Stempien SJ. The Mallory-Weiss syndrome and lesion. A study of 30 cases. Am J Dig Dis. 1966;11:710-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kortas DY, Haas LS, Simpson WG, Nickl NJ, Gates LK. Mallory-Weiss tear: predisposing factors and predictors of a complicated course. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2863-2865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sugawa C, Benishek D, Walt AJ. Mallory-Weiss syndrome. A study of 224 patients. Am J Surg. 1983;145:30-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | DECKER JP, ZAMCHECK N, MALLORY GK. Mallory-Weiss syndrome: hemorrhage from gastroesophageal lacerations at the cardiac orifice of the stomach. N Engl J Med. 1953;249:957-963. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kawano K, Nawata Y, Hamada K, Hiroko T, Noriyuki N, Toshihiro N, Kenji T. Examination about the Mallory-Weiss tear as the accident of ESD. Gastroenterol Endosc. 2012;54:1443-1514. |

| 22. | Corral JE, Keihanian T, Kröner PT, Dauer R, Lukens FJ, Sussman DA. Mallory Weiss syndrome is not associated with hiatal hernia: a matched case-control study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52:462-464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kim JW, Kim HS, Byun JW, Won CS, Jee MG, Park YS, Baik SK, Kwon SO, Lee DK. Predictive factors of recurrent bleeding in Mallory-Weiss syndrome. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2005;46:447-454. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Lecleire S, Antonietti M, Iwanicki-Caron I, Duclos A, Ramirez S, Ben-Soussan E, Hervé S, Ducrotté P. Endoscopic band ligation could decrease recurrent bleeding in Mallory-Weiss syndrome as compared to haemostasis by hemoclips plus epinephrine. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:399-405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Fujisawa N, Inamori M, Sekino Y, Akimoto K, Iida H, Takahata A, Endo H, Hosono K, Sakamoto Y, Akiyama T, Koide T, Tokoro C, Takahashi H, Saito K, Abe Y, Nakamura A, Kubota K, Saito S, Koyama S, Nakajima A. Risk factors for mortality in patients with Mallory-Weiss syndrome. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011;58:417-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ljubičić N, Budimir I, Pavić T, Bišćanin A, Puljiz Z, Bratanić A, Troskot B, Zekanović D. Mortality in high-risk patients with bleeding Mallory-Weiss syndrome is similar to that of peptic ulcer bleeding. Results of a prospective database study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:458-464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Cho YS, Chae HS, Kim HK, Kim JS, Kim BW, Kim SS, Han SW, Choi KY. Endoscopic band ligation and endoscopic hemoclip placement for patients with Mallory-Weiss syndrome and active bleeding. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:2080-2084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Chung IK, Kim EJ, Hwang KY, Kim IH, Kim HS, Park SH, Lee MH, Kim SJ. Evaluation of endoscopic hemostasis in upper gastrointestinal bleeding related to Mallory-Weiss syndrome. Endoscopy. 2002;34:474-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Park CH, Min SW, Sohn YH, Lee WS, Joo YE, Kim HS, Choi SK, Rew JS, Kim SJ. A prospective, randomized trial of endoscopic band ligation vs. epinephrine injection for actively bleeding Mallory-Weiss syndrome. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:22-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Peng YC, Tung CF, Chow WK, Chang CS, Chen GH, Hu WH, Yang DY. Efficacy of endoscopic isotonic saline-epinephrine injection for the management of active Mallory-Weiss tears. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;32:119-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Papp JP. Electrocoagulation of actively bleeding Mallory-Weiss tears. Gastrointest Endosc. 1980;26:128-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Takada J, Araki H, Onogi F, Nakanishi T, Kubota M, Ibuka T, Shimizu M, Moriwaki H. Safety and efficacy of carbon dioxide insufflation during gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:8195-8202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Nakajima K, Moon JH, Tsutsui S, Miyazaki Y, Yamasaki M, Yamada T, Kato M, Yasuda K, Sumiyama K, Yahagi N, Saida Y, Kondo H, Nishida T, Mori M, Doki Y. Esophageal submucosal dissection under steady pressure automatically controlled endoscopy (SPACE): a randomized preclinical trial. Endoscopy. 2012;44:1139-1148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |