Published online Aug 7, 2019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i29.4007

Peer-review started: January 18, 2019

First decision: January 30, 2019

Revised: February 7, 2019

Accepted: February 22, 2019

Article in press: February 23, 2019

Published online: August 7, 2019

Processing time: 202 Days and 20.1 Hours

Anti-epidermal growth factor receptor therapy is associated with skin adverse events not previously reported with conventional chemotherapy. Prophylactic actions are recommended, but routine clinical management of these toxicities and their impact on quality of life remain unknown.

To assess the dermatological toxicities reported after panitumumab initiation, their impact on the quality of life and the clinical practices for their management.

Patients included in this prospective multicenter observational study were over 18 years of age and began treatment with panitumumab for wild-type KRAS metastatic colorectal cancer. The incidence of dermatological toxicities, clinical practices for their management and impact on quality of life were recorded during a 6-mo follow-up.

Overall, 229 patients (males, 57.6%; mean age, 66.2 years) were included. At day 15, 59.3% of patients had dermatological toxicity; the rate peaked at month 2 (74.7%) and decreased at month 6 (46.5%). The most frequent dermatological toxicities were rash/acneiform rash, xerosis and skin cracks. At least one preventive treatment was administered to 65.9% of patients (oral antibiotics, 84.1%; emollients, 75.5%; both, 62.9%). The rates of patients who received at least one curative treatment peaked at month 2 (63.4%) and decreased at month 6 (44.8%). The impact of the dermatological toxicities on quality of life was limited as assessed with Dermatology Life Quality Index scores and inconvenience visual analogic scale score. The rates of topical corticosteroids administration and visits to specialists were low.

The rates of the different skin toxicities peaked at various times and were improved at the end of follow-up. Nevertheless, their clinical management could be optimized with a better adherence to current recommendations. The impact of skin toxicities on patient’s quality of life appeared to be limited.

Core tip: Anti-epidermal growth factor receptor therapy is associated with skin adverse events not previously reported with conventional chemotherapy. Prophylactic actions are recommended, but routine clinical management of these toxicities and their impact on quality of life remain unknown. This observational study describes a cohort of patients who began treatment with panitumumab for metastatic colorectal cancer. The rates of the different skin toxicities peaked at various times and were improved at the end of the follow-up. Nevertheless, their clinical management could be optimized with a better adherence to current recommendations. The impact of skin toxicities on patient’s quality of life appeared to be limited.

- Citation: Bouché O, Ben Abdelghani M, Labourey JL, Triby S, Bensadoun RJ, Jouary T, Des Guetz G. Management of skin toxicities during panitumumab treatment in metastatic colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2019; 25(29): 4007-4018

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v25/i29/4007.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i29.4007

Colorectal cancer is the second most common cancer disease in women and the third most common in men in France. In 2015, the number of new cases was 19500 in women and 23500 in men (8500 and 9300 deaths, respectively)[1]. The treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer is based on chemotherapy protocols. The arsenal of anti-cancer treatments has been expanded by new targeted biotherapies such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors. Thus, panitumumab is an EGFR inhibitor which demonstrated its efficacy in wild-type KRAS metastatic colorectal cancer[2-7]. Unlike conventional chemotherapy, EGFR inhibitors are associated with low hematotoxicity and have a more targeted and specific action on tumor cells than conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy drugs. Nevertheless, new adverse reactions have been reported that include cutaneous effects which are observed in two thirds of patients[8]. These adverse events are not unexpected since EGFR is involved in the physiology of epidermidis. Thus, acneiform papulo-pustular reactions are observed in 50% to 80% of cases and generally occur after the first or second infusion of the drug[8-11]. These reactions always regress when treatment is stopped. Other rarer but also incapacitating skin reactions have been reported, such as eczematiform rashes or paronychia[8-11]. Excessive sun exposure, concomitant radiotherapy and inadequate skin hydration are exacerbating factors for dermatological toxicities associated with EGFR inhibitors.

The dermatological toxicity can have a significant impact on the quality of life of patients, especially in inflammatory and extensive forms affecting the face and leading to poor treatment compliance and need for dosage reduction or even treatment discontinuation[12,13]. At present, no real standards or official recom-mendations exist concerning the management of these skin reactions. Therefore, the management of skin lesions remains empirical and varies according to personal experience. Nevertheless, some recommendations resulting from meetings with oncology and dermatology experts have been published[8,13-16]. A therapeutic algorithm has been proposed by a French interdisciplinary committee[17].

The diagnostic and symptomatic management of these skin toxicities still needs to be improved in order to limit dosage reductions or treatment discontinuations. Another goal is to reduce the impact on quality of life in patients treated for long periods. It is therefore important to describe accurately the skin symptoms and to identify appropriate dermatological treatments, in order to guarantee both the physical and psychological well-being of patients as well as optimum cancer treatment conditions. The purpose of the present study was to assess the dermatological toxicities reported after panitumumab initiation, their impact on the quality of life and the clinical practices for their management.

This was a national, multicenter, descriptive, observational study (POPEC study). Gastroenterologists and oncologists treating colorectal cancer patients were selected and received individual scientific training. A glossary defining precisely the dermatological toxicity was created by the dermatologist of the Scientific Committee and given to the physicians. Physicians saw patients within the context of routine visits, without any special visits being organized for the purposes of the study. The decision to prescribe treatments was freely taken by the clinician prior to the study. The physician-patient relationship and patient follow-up were not modified.

The primary objective was to assess, in patients treated with panitumumab, the incidence, grade and management of the following dermatological toxicities reported at Day 15 after panitumumab (Vectibix®) initiation and at each monthly visit over the 6-month follow-up period: Rash/acneifom rash, skin cracks, paronychia/perionyxis, xerosis, mucositis, hypertrichosis or other. The secondary objective was to assess the impact of dermatological toxicities on quality of life with the 6 dimensions of the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) scores and with the inconvenience visual analogic scale (VAS) score.

The investigating physicians included all consecutive patients seen in consultation who met the following criteria: patients over 18 years of age, beginning treatment or treated for less than two weeks with panitumumab (Vectibix®) in monotherapy for wild-type KRAS metastatic colorectal cancer, after failure of fluoropyrimidine-, oxaliplatin-, and irinotecan-containing chemotherapy regimens or in combination with chemotherapy as follows: In first line in combination with FOLFOX (folinic acid, fluorouracil and oxaliplatin); in second line in combination with FOLFIRI (folinic acid, fluorouracil and irinotecan) for patients who have received first-line fluoro-pyrimidine-based chemotherapy (excluding irinotecan). The patients were followed up for a maximum period of 6 mo. The patients were informed both orally and in writing on the objectives of the study. This study was conducted according to the current revision of the 1964 Helsinki declaration and with the French laws and regulations.

All data collected were obtained from the medical records of the patients. Data with dates before inclusion of the patient (demographic data, medical history, cancer characteristics, performance status, previous chemotherapies and radiotherapy, previous dermatological history and concomitant skin conditions) were collected retrospectively. Prospective data were collected as part of routine patient follow-up: Cancer treatment, performance status, toxicities and management, DLQI questionnaire and inconvenience VAS. A glossary defining precisely the der-matological toxicity created by the dermatologist of the Scientific Committee was given to the physicians.

The DLQI questionnaire included 10 questions scored from 0 (not at all, not relevant, not answered) to 3 (very much). The DLQI score was calculated by summing the scores of each question resulting in a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 30. Higher scores indicate more quality-of-life impairment. DLQI sub-scale scores were: Symptoms and feelings, daily activities, leisure, work and school, personal relationships and treatment. All scores were calculated as recommended by the author, including handling of missing answers for score computation[18]. The VAS reflected, on a 10-cm horizontal line, the inconvenience of skin disorders on patient’s life. Scores ranged from 0 to 10 cm with 0 meaning “no inconvenience at all” and 10 meaning “a great deal of inconvenience”.

Due to the observational nature of the study, the statistical analyses were only descriptive. The primary endpoint was the proportion of dermatological toxicities observed during the study. The secondary endpoints were the DLQI scores and the inconvenience VAS score.

In previous studies, dermatological reactions were reported in almost all patients (around 90%) treated with panitumumab or other EGFR inhibitors. The rates of the different types of dermatological effects induced by anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies ranged from 2%-3% to 60%-80%. It was calculated that a population of 300 patients guaranteed a precision [half-length of 95% confidence interval (CI)] of 2.5% for proportions in the region of 5% and 4.5% in the region of 20%; it did not exceed 6% for higher proportions. In addition, a sample size of 300 patients provided a precision of 3.4% for the 95%CI (86.6%-93.4%) of a proportion of 90%, which corresponds to the proportion of any dermatological reaction observed in patients treated with panitumumab.

The analyses were conducted on all patients enrolled into the study who respected inclusion and exclusion criteria (primary analysis set) and on sub-groups of patients according to age and gender. Age groups were decided by the Scientific Committee and defined during the statistical analysis based on the number of patients observed by age class. The statistical analyses were performed with SAS software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States).

Thirty-nine centers in France included a total of 231 patients from June 2011 to February 2013. Two patients did not meet inclusion criteria: Patients not beginning treatment or treated for more than 2 wk with panitumumab in monotherapy or in combination with chemotherapy for wild-type KRAS metastatic colorectal cancer as required, n = 1 (0.4%); patients not presenting the wild type KRAS gene, n = 1 (0.4%). Therefore, the primary analysis set included 229 patients. During the 6-mo follow-up, 142 patients (62.0%) discontinued the study. The reasons for discontinuation were death (n = 78), disease progression (n = 46), lost to follow-up (n = 4) or others (n = 14).

The primary analysis set included 97 women (42.4%) and 132 men (57.6%) with a mean age of 66.2 years; 29.7% had an age ≥ 75 years (Table 1). The mean duration between inclusion and diagnosis of colorectal cancer was 2.9 years and was 2.0 years for metastatic diagnosis. The most frequent metastatic sites were liver (74.2%) and lung (40.2%). Serine/threonine-protein kinase B-Raf (BRAF) genotyping was performed in 31.1% of patients; when performed, mutated BRAF was evidenced in 7.1% of patients. Previous radiotherapy treatment had been received by 27.3% of patients and previous adjuvant chemotherapy by 44.5%. In the context of the metastatic disease, 90.4% received chemotherapy and 13.1% radiotherapy (Table 1). A history of skin disorders was reported for 17.0% of patients and 5.7% of patients had skin disorders at inclusion.

| n | Results | |

| Male gender, n (%) | 229 | 132 (57.6) |

| Age (yr) | 229 | |

| Mean (SD) | 229 | 66.2 (11.5) |

| ≥ 75, n (%) | 229 | 68 (29.7) |

| Cancer other than metastatic colorectal cancer, n (%) | 228 | 20 (8.8) |

| Duration since diagnosis of primary disease (yr), mean (SD) | 226 | 2.9 (2.3) |

| Duration since diagnosis of metastatic disease (yr), mean (SD) | 227 | 2.0 (1.5) |

| Metastatic sites, n (%) | ||

| Liver | 229 | 170 (74.2) |

| Lung | 229 | 92 (40.2) |

| Peritoneum | 229 | 38 (16.6) |

| Lymph nodes | 229 | 59 (25.8) |

| Bone | 229 | 10 (4.4) |

| Other | 229 | 29 (12.7) |

| BRAF genotyping performed, n (%) | 225 | 70 (31.1) |

| If performed, BRAF genotyping | ||

| Non-mutated BRAF | 70 | 62 (88.6) |

| Mutated BRAF | 70 | 5 (7.1) |

| BRAF not assessable | 70 | 3 (4.3) |

| Previous radiotherapy treatment (any cancer), n (%) | 227 | 62 (27.3) |

| Previous adjuvant chemotherapya, n (%) | 227 | 101 (44.5) |

| Previous chemotherapy for metastatic diseaseb, n (%) | 229 | 207 (90.4) |

| Total treatment duration, weeks, mean (SD) | ||

| Line 1 | 207 | 26.3 (21.9) |

| Line 2 | 165 | 23.0 (20.5) |

| Line 3 | 97 | 19.9 (17.1) |

| Line 4 | 24 | 19.9 (17.6) |

| Previous radiotherapy for metastatic disease, n (%) | 30 (13.1) | |

| Abdominal lymph nodes | 218 | 5 (26.3) |

| Pelvic | 221 | 10 (45.5) |

| Other | 221 | 18 (81.8) |

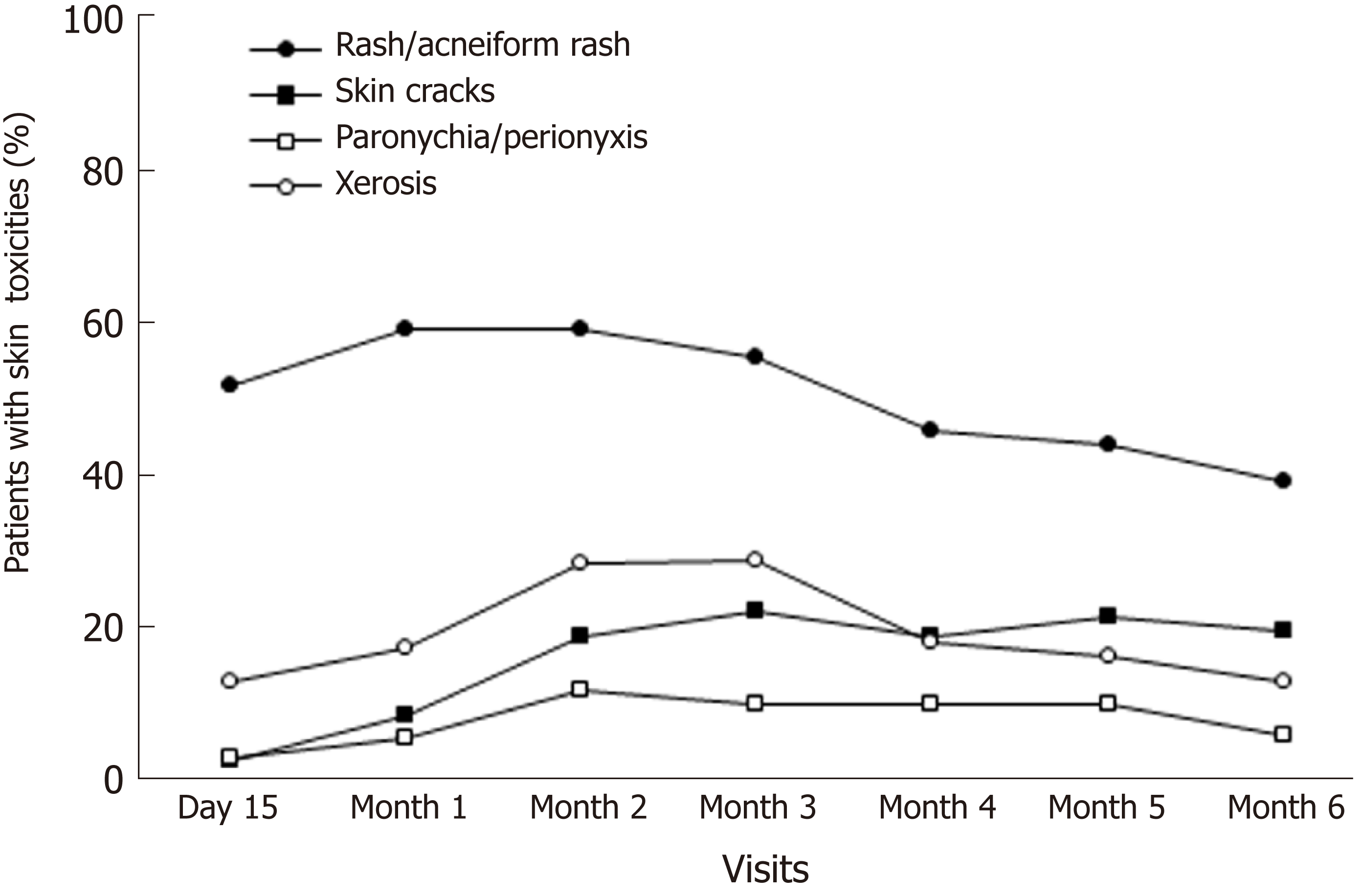

The rates of patients with at least one dermatological toxicity during the 6-mo follow-up are described in Table 2. At day 15, more than half of patients had dermatological toxicity (59.3%); the rate peaked at month 2 (74.7%) and decreased at Month 6 (46.5%). Among patients with dermatological toxicity, those with rash/acneiform rash were the most frequent (at least 3/4 of patients with skin toxicity at each visit) (Figure 1). Patients with xerosis were also frequent: 21.3% at day 15, 41.1% at month 3 and 27.5% at month 6. The rate of patients with skin cracks steadily increased from 3.9% at day 15 to 42.5% at month 6.

| Day 15 (n = 214) | Month 1 (n = 208) | Month 2 (n = 186) | Month 3 (n = 153) | Month 4 (n = 122) | Month 5 (n = 93) | Month 6 (n = 87) | |

| At least one dermatological toxicity, n (%) | 127 (59.3) | 141 (67.8) | 139 (74.7) | 107 (69.9) | 76 (63.3) | 52 (57.1) | 40 (46.5) |

| Dermatological toxicities | |||||||

| Rash/acneiform rash, n (%) | 111 (51.9) | 123 (59.1) | 110 (59.1) | 85 (55.6) | 56 (45.9) | 41 (44.1) | 34 (39.1) |

| Grade 1-2 | 101 (47.2) | 115 (55.3) | 99 (53.2) | 82 (53.6) | 51 (41.8) | 39 (41.9) | 33 (37.9) |

| Grade 3-4 | 10 (4.7) | 7 (3.4) | 8 (4.3) | 2 (1.1) | 4 (3.2) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.1) |

| Grade missing | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Skin cracks, n (%) | 5 (2.3) | 17 (8.2) | 35 (18.8) | 34 (22.2) | 23 (18.9) | 20 (21.5) | 17 (19.5) |

| Grade 1-2 | 4 (1.9) | 16 (7.7) | 32 (17.2) | 33 (21.6) | 22 (18.0) | 19 (20.4) | 17 (19.8) |

| Grade 3-4 | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1.6) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 0 |

| Grade missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Paronychia/Perionyxis, n (%) | 6 (2.8) | 11 (5.3) | 22 (11.8) | 15 (9.8) | 12 (9.8) | 9 (9.7) | 5 (5.7) |

| Grade 1-2 | 6 (2.8) | 10 (4.8) | 21 (11.3) | 15 (9.8) | 12 (9.8) | 8 (8.6) | 5 (5.7) |

| Grade 3-4 | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.1) | 0 |

| Xerosis, n (%) | 27 (12.6) | 36 (17.3) | 53 (28.5) | 44 (28.8) | 22 (18.0) | 15 (16.1) | 11 (12.6) |

| Grade 1-2 | 27 (12.6) | 34 (16.3) | 51 (27.4) | 43 (28.1) | 21 (17.2) | 15 (16.1) | 11 (12.6) |

| Grade 3-4 | 0 | 2 (1.0) | 2 (1.1) | 0 | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 0 |

| Grade missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mucositis, n (%) | 12 (5.6) | 15 (7.2) | 19 (10.2) | 8 (5.2) | 3 (2.5) | 3 (3.2) | 2 (2.3) |

| Grade 1-2 | 12 (5.6) | 15 (7.2) | 18 (9.7) | 8 (5.2) | 3 (2.5) | 3 (3.2) | 2 (2.3) |

| Grade 3-4 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypertrichosis, n (%) | 1 (0.5) | 4 (1.9) | 5 (2.7) | 7 (4.6) | 7 (5.7) | 2 (2.2) | 2 (2.3) |

| Grade 1-2 | 1 (0.5) | 4 (1.9) | 5 (2.7) | 7 (4.6) | 7 (5.7) | 2 (2.2) | 2 (2.3) |

| Other, n (%) | 5 (2.3) | 5 (2.4) | 4 (2.2) | 4 (2.6) | 3 (2.5) | 0 | 1 (1.1) |

| Grade 1-2 | 5 (2.3) | 5 (2.4) | 4 (2.2) | 4 (2.6) | 3 (2.5) | 0 | 1 (1.1) |

Other dermatological toxicities (paronychia/perionyxis, mucositis, hypertrichosis, other) involved lower numbers of patients (Table 2). Most skin toxicities were grade 1-2. Factors associated with dermatological toxicities have been analyzed: Sex, age, duration since primary disease, duration metastatic disease, metastatic sites, previous adjuvant chemotherapy, previous chemotherapy for metastatic disease, previous radiotherapy for metastatic disease, history of skin conditions, and preventive treatment for dermatological toxicities. No factor appeared to be more frequently associated with dermatological toxicities.

The mean dosage of panitumumab dosage per injection at baseline was 6.0 mg/kg (recommended dose every two weeks) and it did not significantly change during the 6-mo follow-up. Panitumumab treatment was discontinued in 68.2% (150/220) of patients during the 6-mo follow-up. For patients with treatment discontinuation, the mean (SD) duration of treatment before discontinuation was 80.4 (50.8) d. The main reason for discontinuation was related to disease progression (68.7%, 103/150) and toxicity (18.7%, 28/150). There was no discontinuation related to allergic episode. Skin toxicity accounted for 46% (13/28) of all cases of discontinuations related to toxicity. Doses delayed and/or dose adjustment (decrease) in patients with skin toxicities occurred mainly from month 3 including grade 1-2 toxicities. Thus, for rash/acneiform rash grade 1-2, 25.9% (21/81) of patients had delayed dose at month 3 and 25.5% (12/47) had dose adjustment at month 4 (Table 3).

| Day 15 (n = 214) | Month 1 (n = 208) | Month 2 (n = 186) | Month 3 (n = 153) | Month 4 (n = 122) | Month 5 (n = 93) | Month 6 (n = 87) | |

| Rash/acneiform rash, grade 1-2, n | 101 | 115 | 99 | 82 | 51 | 39 | 33 |

| Doses delayed, n (%) | 2 (2.0) | 4 (3.5) | 13 (13.1) | 21 (25.9) | 4 (7.8) | 4 (10.3) | 9 (27.3) |

| MD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dose adjustment, n (%) | 0 | 7 (6.3) | 3 (3.3) | 13 (16.9) | 12 (25.5) | 8 (20.5) | 6 (18.2) |

| MD | 1 | 3 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 3 |

| Rash/acneiform rash, grade 3-4, n | 10 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Doses delayed, n (%) | 1 (10.0) | 1 (14.3) | 4 (50.0) | 2 (100) | 1 (25.0) | 0 | 0 |

| MD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dose adjustment, n (%) | 2 (25.0) | 0 | 2 (33.3) | 2 (100) | 1 (25.0) | 0 | 0 |

| MD | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Study patients frequently received preventive treatment (at least one treatment for 65.9% of them) (Table 4). When preventive treatment was administered, the most frequent were oral antibiotics (84.1%), emollients (75.5%) or emollients plus oral antibiotics (62.9%). Topical corticosteroids were administered as preventive treatment in 9.3% of patients.

| n = 229 | |

| At least one preventive treatment, n (%) | 151/229 (65.9) |

| Emollients | 114/151 (75.5) |

| Oral antibiotics | 127/151 (84.1) |

| Emollients and oral antibiotics | 95/151 (62.9) |

| Sunscreen | 9/150 (6.0) |

| Topical corticosteroids | 14/151 (9.3) |

| Other (including topical antibiotics) | 33/151 (21.9) |

| Topical antibiotics | 30/33 (90.9) |

The curative treatments of dermatological toxicities are described in Table 5. At least one curative treatment was administered to a majority of patients during the 6-mo follow-up. This rate was maximal at month 2 (63.4%). Antibiotics plus emollients were administered to a majority of patients (51.7% at month 2) who received curative treatment (treatment duration was about one mo). Topical corticosteroids were administered to about one patient out of five who received curative treatment (treatment duration ranged from 2 wk to one month).

| Day 15 (n = 214) | Month 1 (n = 208) | Month 2 (n = 186) | Month 3 (n = 153) | Month 4 (n = 122) | Month 5 (n = 93) | Month 6 (n = 87) | |

| At least one curative treatment, n (%) | 117/214 (54.7) | 124/208 (59.6) | 118/186 (63.4) | 92/153 (60.1) | 63/120 (52.5) | 47/92 (51.1) | 39/87 (44.8) |

| Emollients | 74 (63.2) | 82 (66.1) | 84 (71.2) | 69 (75.0) | 45 (71.4) | 29 (61.7) | 24 (61.5) |

| Oral antibiotics | 88 (75.2) | 90 (72.6) | 88 (74.6) | 65 (70.7) | 43 (68.3) | 31 (66.0) | 28 (71.8) |

| Emollients and oral antibiotics | 60 (51.3) | 61 (49.2) | 61 (51.7) | 47 (51.1) | 28 (44.4) | 17 (36.2) | 16 (41.0) |

| Antiseptics | 9 (7.8) | 7 (5.6) | 11 (9.3) | 7 (7.6) | 2 (3.2) | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Antihistamines | 12 (10.3) | 10 (8.1) | 11 (9.4) | 10 (10.9) | 6 (9.5) | 5 (10.6) | 2 (5.1) |

| Corticosteroids | 19 (16.2) | 26 (21.0) | 23 (19.5) | 19 (20.7) | 12 (19.0) | 6 (12.8) | 9 (23.1) |

| Other (including topical antibiotics) | 51 (44.0) | 47 (37.9) | 35 (29.7) | 29 (31.9) | 20 (31.7) | 16 (34.0) | 13 (33.3) |

| Topical antibiotics | 48 (94.1) | 43 (91.5) | 30 (85.7) | 25 (86.2) | 18 (90.0) | 16 (100) | 13 (100) |

A small proportion of patients required at least one specialized consultation for dermatological toxicities (about 8% for the first two mo and about 5% for the next months). The specialists consulted by these patients were mainly dermatologists (70%), psychologists (22%) and oncology estheticians (14%). Patients with dermatological toxicities consulted more frequently specialists. From 0% to 6.0% at each monthly visit in the absence of toxicity and from 6.5% to 11.0% in the presence of toxicity.

A slight increase of mean DLQI total score from baseline was observed for the entire population with a peak at month 3: From 0.9 at baseline to 3.7 at month 3 (n = 149) for a maximum score equal to 30. The same analysis was performed only in patients with dermatological toxicities and comparable results were observed: From 1.0 at baseline to 4.0 at month 3 (n = 91). The mean inconvenience VAS score increased from 1.5 at baseline (n = 184) to 3.2 at month 3 (n = 95) and decreased to 2.4 at month 6 (n = 50) for the entire population, thus indicating a moderate inconvenience during the 6-mo follow-up. Comparable results were obtained in the sub-group of patients with dermatological toxicities (1.6 at baseline, n = 140; 3.2 at month 3, n = 87; and 2.5 at month 6, n = 48).

This observational study included 229 patients with wild-type KRAS colorectal cancer with a mean age of 66.2 years. The inclusion criteria fitted the indications of panitumumab; demographic data and patient characteristics were representative of the population of patients treated with panitumumab.

One of the strengths of this study is the assessment of the kinetics of skin toxicities during a 6-mo follow-up. The rate of patients with dermatological toxicity peaked at month 2 (74.7%). The most frequent dermatological toxicities were rash/acneiform rash (at least 3 out 4 patients at each monthly visit). Patients with xerosis were also frequent. The rate of patients with skin cracks steadily increased from during the follow-up. These findings confirm previous reports on time-course of the most common skin adverse events associated with panitumumab[19]. Thus, the earliest and most common skin adverse events are rashes/acneiform rashes[19]. These rashes differ from true acne since no cystic lesions or comedones are associated.

When the study was performed, there was no clinical and patient guidance for these frequent skin lesions and their management remained empirical. Preemptive treatments are currently the preferred approach[20]. Emollients and antihistamines are often used[21]. For acneiform rashes, class II or III topical corticosteroids are proposed[9,22]. Systemic treatments such as doxycycline have also been proposed. For widespread eczematiform rashes, treatment is primarily preventive, based on avoidance of sun exposure and the use of sunscreens with very high protection[9]. Due to possible spontaneous improvement, it is difficult to assess the efficacy of these dermatological treatments. However, the STEPP study showed that preemptive treatment of dermatological toxicities compared with reactive treatment led to more than 50% reduction skin toxicities with grade ≥ 2 and was associated with an improvement of the quality of life and no change in response rates[23]. Preemptive treatment consisted of skin moisturizer, sunscreen, topical steroid and doxycycline 100 mg twice per day[23]. These results were confirmed in a similar study (J-STEPP) performed in 95 Japanese patients with metastatic colorectal cancer with a 6-wk follow-up[24]. The cumulative incidence of skin toxicities with grade ≥ 2 were lower for preemptive treatment compared to reactive treatment (21.3% vs 62.5%; risk ratio: 0.34; P < 0.001). In a meta-analysis, the rate of skin rash due to anti-EGFR treatment was significantly decreased in patients with solid tumors who received prophylactic treatment with antibiotics (odds-ratio, 0.53; 95%CI 0.39-0.72; P < 0.01)[25].

In our study, only 65.9% of patients received at least one preventive treatment; the most frequent were oral antibiotics (84.1%), emollients (75.5%) or emollients plus oral antibiotics (62.9%). Only 9.3% of patients were administered topical corticosteroids as preventive treatment. Indeed, local treatments with corticosteroids are not recommended in French guidelines[17]. At least one curative treatment was administered to a majority of patients during the entire 6-month follow-up. Among patients with curative treatment, antibiotics and emollients were administered to a majority of them at each visit and corticosteroids were administered to very few patients (about one patient out of five). Overall, these results indicate that the rate of preventive treatments, although recommended, was relatively low with two patients out three; emollient and oral antibiotics were preventively administered together to 62.9% of patients.

The summary of product characteristics of panitumumab recommends the suspension of treatment for 1 or 2 doses and a possible continuation at a lower dose only for adverse events grade ≥ 3. In our study, the rates of doses delayed and dose adjustments were relatively high even in patients with low grade skin toxicity. Thus, in patients with rash/acneiform rash grade 1-2, the dose was delayed for 25.9% of them at month 3 and the dose was adjusted for 25.5% at month 4; these rates remained high for the next months. It remains unclear whether these high rates of doses delayed/adjustments were related to patient willingness and/or physician decision. One possibility is that some skin toxicities classified as low grade are nevertheless unbearable for a number of patients. In contrast, in the STEPP study, the doses of panitumumab were adjusted in only 1% of patients in patients with skin toxicities of grade ≥ 2 in the preemptive treatment group and 6% in the curative treatment group[23].

Previous surveys in Germany, United States and France have been performed in practitioners treating colorectal cancer patients with EGFR inhibitors[26-28]. Overall these surveys reported a disparity in terms of grade assessment and management of skin toxicities. As observed in the present study, consultations to dermatologists were not frequent; in the French survey of Peuvrel et al[28], visits to dermatologists were planned for persisting or worsening lesions beyond two weeks, but never at the initiation of treatment.

The impact of the dermatological toxicities on the quality of life in our study was limited as assessed with DLQI scores and inconvenience VAS score. No differences according to age or gender were observed for dermatological toxicities, management and impact on patient’s quality of life. These results are consistent with the recent study of Koukakis et al[29] that summarized data from three clinical trials with panitumumab in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. No significant difference was observed between panitumumab and comparator groups for the score of quality of life and overall health.

The limitations of this study are common to any observational study. It was planned to enroll 300 patients and only 231 were included. In addition, the rate of study discontinuation was high (62.0%); the main reasons for discontinuations were death and disease progression. However, the development of cutaneous side effects during treatment with EGFR inhibitors appears to have a major prognostic significance. In initial phase II trials, it was shown that patients who developed skin lesions lived longer than those who did not. In addition, higher response rates and longer survival times were observed as a function of the severity of the skin rash[9,10,14]. Although this notion remains controversial, it is possible that the rates of dermatological toxicities were overestimated for the late time points of the study due to a possible selection of patients with improved outcome over time. When the study was performed, there was no guidelines for skin toxicities in this setting[20]. Therefore, the management of patients with dermatological toxicities could have benefited from their inclusion in the study. Physicians who included patients received information that could have modify their habits for the management of these dermatological toxicities.

In conclusion, the rates of the different skin toxicities peaked at various times and were improved at the end of the follow-up. Nevertheless, their clinical management could be optimized with a better adherence to current recommendations. The impact of skin toxicities on patient’s quality of life appeared to be limited.

Skin adverse events not previously reported with conventional chemotherapy are associated with anti-epidermal growth factor receptor therapy.

Although prophylactic actions are recommended to prevent these skin toxicities, routine clinical management and impact on quality of life remain unknown.

The present study aimed to assess the dermatological toxicities reported after panitumumab initiation, their impact on the quality of life and the clinical practices for their management.

We performed a prospective multicenter observational study in 229 adult patients who began treatment with panitumumab for wild-type KRAS metastatic colorectal cancer. The incidence of dermatological toxicities, clinical practices for their management and impact on quality of life were recorded during a 6-mo follow-up.

More than half of patients had dermatological toxicity; this rate peaked at month 2. The most frequent dermatological toxicities were rash/acneiform rash, xerosis and skin cracks. At least one preventive treatment was administered to two thirds of patients (oral antibiotics, emollients or both). The impact of the dermatological toxicities on quality of life was limited.

The rates of the different skin toxicities peaked at various times and were improved at the end of follow-up. The impact of skin toxicities on patient’s quality of life appeared to be limited.

The management of the skin toxicities could be optimized with a better adherence to current recommendations.

Francis Beauvais (Scientific and Medical Writing, Sèvres) provided writing services, which were funded by Amgen.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: France

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Augustin G, Chan AT, Luglio G S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A E-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Leone N, Voirin N, Roche L, Binder-Foucard F, Woronoff A, Delafosse P, Remontet L, Bossard N, Uhry Z. Projection de l’incidence et de la mortalité par cancer en France métropolitaine en 2015. Rapport technique. Saint-Maurice (Fra): Institut de veille sanitaire 2015; 62 Available from: http://invs.santepubliquefrance.fr/Publications-et-outils/Rapports-et-syntheses/Maladies-chroniques-et-traumatismes/2015/Projection-de-l-incidence-et-de-la-mortalite-par-cancer-en-France-metropolitaine-en-2015. |

| 2. | Douillard JY, Oliner KS, Siena S, Tabernero J, Burkes R, Barugel M, Humblet Y, Bodoky G, Cunningham D, Jassem J, Rivera F, Kocákova I, Ruff P, Błasińska-Morawiec M, Šmakal M, Canon JL, Rother M, Williams R, Rong A, Wiezorek J, Sidhu R, Patterson SD. Panitumumab-FOLFOX4 treatment and RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1023-1034. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1610] [Cited by in RCA: 1730] [Article Influence: 144.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hocking CM, Price TJ. Panitumumab in the management of patients with KRAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2014;7:20-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nishi T, Hamamoto Y, Nagase M, Denda T, Yamaguchi K, Amagai K, Miyata Y, Yamanaka Y, Yanai K, Ishikawa T, Kuroki Y, Fujii H. Phase II trial of panitumumab with irinotecan as salvage therapy for patients with advanced or recurrent colorectal cancer (TOPIC study). Oncol Lett. 2016;11:4049-4054. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zaniboni A, Formica V. The Best. First. Anti-EGFR before anti-VEGF, in the first-line treatment of RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer: From bench to bedside. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2016;78:233-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yamaguchi T, Iwasa S, Nagashima K, Ikezawa N, Hamaguchi T, Shoji H, Honma Y, Takashima A, Okita N, Kato K, Yamada Y, Shimada Y. Comparison of Panitumumab Plus Irinotecan and Cetuximab Plus Irinotecan for KRAS Wild-type Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2016;36:3531-3536. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Takaoka T, Kimura T, Shimoyama R, Kawamoto S, Sakamoto K, Goda F, Miyamoto H, Negoro Y, Tsuji A, Yoshizaki K, Goji T, Kitamura S, Yano H, Okamoto K, Kimura M, Okahisa T, Muguruma N, Niitsu Y, Takayama T. Panitumumab in combination with irinotecan plus S-1 (IRIS) as second-line therapy for metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2016;78:397-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lynch TJ, Kim ES, Eaby B, Garey J, West DP, Lacouture ME. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor-associated cutaneous toxicities: An evolving paradigm in clinical management. Oncologist. 2007;12:610-621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 250] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Guillot B, Bessis D. Aspects cliniques et prise en charge des effets secondaires cutanés des inhibiteurs du récepteur à l’EGF. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2006;133:1017-1020. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Peréz-Soler R, Saltz L. Cutaneous adverse effects with HER1/EGFR-targeted agents: Is there a silver lining? J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5235-5246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 371] [Cited by in RCA: 359] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Segaert S, Van Cutsem E. Clinical signs, pathophysiology and management of skin toxicity during therapy with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:1425-1433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 386] [Cited by in RCA: 375] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wagner LI, Lacouture ME. Dermatologic toxicities associated with EGFR inhibitors: The clinical psychologist’s perspective. Impact on health-related quality of life and implications for clinical management of psychological sequelae. Oncology (Williston Park). 2007;21:34-36. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Bouché O, Scaglia E, Reguiai Z, Singha V, Brixi-Benmansour H, Lagarde S. [Targeted biotherapies in digestive oncology: Management of adverse effects]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2009;33:306-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Pérez-Soler R, Delord JP, Halpern A, Kelly K, Krueger J, Sureda BM, von Pawel J, Temel J, Siena S, Soulières D, Saltz L, Leyden J. HER1/EGFR inhibitor-associated rash: Future directions for management and investigation outcomes from the HER1/EGFR inhibitor rash management forum. Oncologist. 2005;10:345-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Melosky B, Burkes R, Rayson D, Alcindor T, Shear N, Lacouture M. Management of skin rash during EGFR-targeted monoclonal antibody treatment for gastrointestinal malignancies: Canadian recommendations. Curr Oncol. 2009;16:16-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Potthoff K, Hofheinz R, Hassel JC, Volkenandt M, Lordick F, Hartmann JT, Karthaus M, Riess H, Lipp HP, Hauschild A, Trarbach T, Wollenberg A. Interdisciplinary management of EGFR-inhibitor-induced skin reactions: A German expert opinion. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:524-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Reguiai Z, Bachet JB, Bachmeyer C, Peuvrel L, Beylot-Barry M, Bezier M, Boucher E, Chevelle C, Colin P, Guimbaud R, Mineur L, Richard MA, Artru P, Dufour P, Gornet JM, Samalin E, Bensadoun RJ, Ychou M, André T, Dreno B, Bouché O. Management of cutaneous adverse events induced by anti-EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor): A French interdisciplinary therapeutic algorithm. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:1395-1404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)--a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3004] [Cited by in RCA: 3531] [Article Influence: 113.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hofheinz RD, Segaert S, Safont MJ, Demonty G, Prenen H. Management of adverse events during treatment of gastrointestinal cancers with epidermal growth factor inhibitors. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2017;114:102-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hofheinz RD, Deplanque G, Komatsu Y, Kobayashi Y, Ocvirk J, Racca P, Guenther S, Zhang J, Lacouture ME, Jatoi A. Recommendations for the Prophylactic Management of Skin Reactions Induced by Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibitors in Patients With Solid Tumors. Oncologist. 2016;21:1483-1491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Molinari E, De Quatrebarbes J, André T, Aractingi S. Cetuximab-induced acne. Dermatology. 2005;211:330-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Jacot W, Bessis D, Jorda E, Ychou M, Fabbro M, Pujol JL, Guillot B. Acneiform eruption induced by epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors in patients with solid tumours. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:238-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lacouture ME, Mitchell EP, Piperdi B, Pillai MV, Shearer H, Iannotti N, Xu F, Yassine M. Skin toxicity evaluation protocol with panitumumab (STEPP), a phase II, open-label, randomized trial evaluating the impact of a pre-Emptive Skin treatment regimen on skin toxicities and quality of life in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1351-1357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 315] [Cited by in RCA: 340] [Article Influence: 22.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kobayashi Y, Komatsu Y, Yuki S, Fukushima H, Sasaki T, Iwanaga I, Uebayashi M, Okuda H, Kusumi T, Miyagishima T, Sogabe S, Tateyama M, Hatanaka K, Tsuji Y, Nakamura M, Konno J, Yamamoto F, Onodera M, Iwai K, Sakata Y, Abe R, Oba K, Sakamoto N. Randomized controlled trial on the skin toxicity of panitumumab in Japanese patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: HGCSG1001 study; J-STEPP. Future Oncol. 2015;11:617-627. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Petrelli F, Borgonovo K, Cabiddu M, Coinu A, Ghilardi M, Lonati V, Barni S. Antibiotic prophylaxis for skin toxicity induced by antiepidermal growth factor receptor agents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:1166-1174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hassel JC, Kripp M, Al-Batran S, Hofheinz RD. Treatment of epidermal growth factor receptor antagonist-induced skin rash: Results of a survey among German oncologists. Onkologie. 2010;33:94-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Boone SL, Rademaker A, Liu D, Pfeiffer C, Mauro DJ, Lacouture ME. Impact and management of skin toxicity associated with anti-epidermal growth factor receptor therapy: Survey results. Oncology. 2007;72:152-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Peuvrel L, Bachmeyer C, Reguiai Z, Bachet JB, André, T, Bensadoun RJ, Bouché, O, Ychou M, Dré, no B, Regional expert groups PROCUR. Survey on the management of skin toxicity associated with EGFR inhibitors amongst French physicians. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:419-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Koukakis R, Gatta F, Hechmati G, Siena S. Skin toxicity and quality of life during treatment with panitumumab for RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal carcinoma: Results from three randomised clinical trials. Qual Life Res. 2016;25:2645-2656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |