Published online May 14, 2019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i18.2229

Peer-review started: February 6, 2019

First decision: March 14, 2019

Revised: March 21, 2019

Accepted: April 10, 2019

Article in press: April 10, 2019

Published online: May 14, 2019

Processing time: 102 Days and 10.1 Hours

The hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS5A inhibitor ABT-267 (ombitasvir, OBV), the HCV NS4/4A protease inhibitor ABT-450 (paritaprevir, PTV), the CYP3A inhibitor ritonavir (r) and the non-nucleoside NS5B polymerase inhibitor ABT-333 (dasabuvir, DSV) (OBV/PTV/r + DSV) with or without ribavirin (RBV) is a direct-acting antiviral regimen approved in the United States and other major countries for the treatment of HCV in genotype 1 (GT1) infected patients. Patients with HCV who are considered “hard-to-cure” have generally been excluded from registration trials due to rigorous study inclusion criteria, presence of comorbidities and previous treatment failures.

To investigate the efficacy of this regimen in HCV G1-infected patients historically excluded from clinical trials.

Patients were ≥ 18 years old and chronically infected with HCV GT1 (GT1a, GT1b or GT1a/1b). Patients were treatment-naïve or previously failed a regimen including pegylated interferon/RBV +/- telaprevir, boceprevir, or simeprevir. One hundred patients were treated with the study drug regimen, which was administered for 12 or 24 wk +/- RBV according to GT1 subtype and presence/absence of cirrhosis. Patients were evaluated every 4 wk from treatment day 1 and at 4 and 12 wk after end-of-treatment.

Many of the patients studied had comorbidities (44.2% hypertensive, 33.7% obese, 20.2% cirrhotic) and 16% previously failed HCV treatment. Ninety-six patients completed study follow-up and 99% achieved 12-wk sustained virologic response. The majority (88.4%) of patients had undetectable HCV RNA by week 4. The most common adverse events were fatigue (12%), headache (10%), insomnia (9%) and diarrhea (8%); none led to treatment discontinuation. Physical and mental patient reported outcomes scores significantly improved after treatment. Almost all (98%) patients were treatment compliant.

In an all-comers HCV GT1 population, 12 or 24-wk of OBV/PTV/r + DSV +/- RBV is highly effective and tolerable and results in better mental and physical health following treatment.

Core tip: The hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS5A inhibitor ABT-267 (ombitasvir, OBV), HCV NS4/4A protease inhibitor ABT-450 (paritaprevir, PTV), CYP3A inhibitor ritonavir (r) and non-nucleoside NS5B polymerase inhibitor ABT-333 (dasabuvir, DSV) (OBV/PTV/r + DSV) with or without ribavirin (RBV) is an approved direct-acting antiviral regimen less frequently studied in an all-comers population. This study included 96 all-comers; many had comorbidities (44.2% hypertensive, 33.7% obese, 20.2% cirrhotic) and 16% previously failed HCV treatment. In these patients, 12 or 24-wk of OBV/PTV/r + DSV +/- RBV was highly effective (99% sustained virologic response for 12 wk treatment), tolerable and resulted in better mental and physical health.

- Citation: Loo N, Lawitz E, Alkhouri N, Wells J, Landaverde C, Coste A, Salcido R, Scott M, Poordad F. Ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir + dasabuvir +/- ribavirin in real world hepatitis C patients. World J Gastroenterol 2019; 25(18): 2229-2239

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v25/i18/2229.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i18.2229

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) approximates that 3.2 million hepatitis C virus (HCV) patients are living in the United States[1]. Among these patients, most will develop chronic infection that can ultimately lead to hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis[2]. Cirrhotic HCV patients have an increased risk of developing decompensated cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[3,4]. and commonly require liver transplantation[5].

The recent era of improved treatment regimens for HCV has contributed to much better outcomes in these patients[6], with the goal of treatment being to eradicate the virus and prevent the development of cirrhosis and its complications. Successful treatment of HCV is defined in terms of sustained virologic response (SVR), which is undetectable levels of HCV viral RNA in the blood 12 wk after completion of therapy[7]. Currently, treatment for HCV involves the use of direct-acting antiviral (DAA) regimens, which are molecules that target specific nonstructural proteins of the virus and disrupt viral replication and infection. One such DAA regimen is the HCV NS5A inhibitor ombitasvir (OBV), HCV NS4/4A protease inhibitor paritaprevir (PTV), the CYP3A inhibitor ritonavir and the non-nucleoside NS5B polymerase inhibitor dasabuvir (DSV) (OBV/PTV/r + DSV) with or without ribavirin (RBV). In registration trials for this regimen, SVR rates reached as high as 99% in HCV genotype 1 (GT1) patients[8].

Patients with HCV who are considered “hard-to-cure” have generally been excluded from registration trials due to rigorous study inclusion criteria, presence of comorbidities and previous treatment failures. Here we report the results of a phase 4, open label study that evaluated the safety and efficacy of OBV/PTV/r + DSV +/- RBV in a real-world clinical setting in patients who have historically been excluded from clinical trials. We also report on the patient quality of life, dosing adherence and whether resistance-associated substitutions (RASs) impact achievement of SVR.

All patients provided written informed consent. The study was conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation, applicable regulations, and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Upon signing the informed consent, patients were considered enrolled and screening and baseline assessments were initiated. Patients were screened from April 21, 2016 through December 5, 2016. Screening procedures at baseline included a medical history, physical exam, blood chemistries, HCV RNA PCR and HCV genotype assessments.

Eligible patients were ≥ 18 years old and chronically infected with HCV GT1 (GT1a, GT1b or GT1a/1b). Patients were either treatment naïve or previously failed a regimen including pegylated interferon (pegIFN)/RBV with or without telaprevir, boceprevir, or simeprevir. Patients were excluded from the study if they were currently taking or planning on taking any medications contraindicated in the OBV/PTV/r + DSV package insert, had evidence of decompensated liver disease (Child-Pugh B or C, including the presence of clinical ascites, bleeding varices, or hepatic encephalopathy), hemoglobin < 8 g/dL, platelets < 25000 cells/mm3, all nucleated cells < 500 cells/mm3, bilirubin > 3, international normalized ratio ≥ 2.3, serum albumin < 2.8 and glomerular filtration rate < 30 mL, alanine aminotransferase or aspartate aminotransferase > 10 × ULN, consume > 3 alcoholic drinks daily or have uncontrolled HIV or hepatitis B virus coinfection. Patients with cirrhosis were required to have serum alpha fetoprotein < 100 ng/mL and imaging ruling out HCC within 3 mo of screening visit.

Treatment was initiated when screening and baseline procedures were completed, and patient eligibility was confirmed. Patients received the US package insert recommended dose: Two OBV/PTV/r 12.5/75/50 mg tablets once daily (in the morning) and one DSV 250 mg tablet twice daily (morning and evening) with a meal without regard to fat or calorie content. RBV was given to some patients based on approved US package insert and was dosed at 1000 mg/d (< 75 kg) or 1200 mg/d (≥ 75 kg), divided and administered twice-daily with food. Duration of treatment was determined based on GT1 subtype and the presence or absence of cirrhosis. GT1a patients with compensated cirrhosis were treated for 24 wk including RBV, GT1a patients without cirrhosis and GT1b patients with compensated cirrhosis were treated for 12 wk including RBV, and GT1b patients without compensated cirrhosis were treated for 12 wk without RBV.

For patients treated for 12 wk, study visits took place at day 1 (baseline) and weeks 4, 8 and 12 (end-of-treatment, EOT). For patients treated for 24 wk, study visits took place at day 1 (baseline) and weeks 4, 8, 12, 16, 20 and 24 (EOT). All patients had follow-up visits 4 and 12 wk after their last dose of study medication. Patients were considered to be off study if they discontinued early or did not complete protocol defined visits. The study protocol was approved by the Integ Review Institutional Review Board. The study was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov.

The primary endpoint was SVR 12 wk after the last treatment dose for the all treated population. The all treated population was defined as all patients that were consented and received at least 1 dose of study medication. SVR was defined as HCV RNA below the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) 12 wk after the end of treatment (SVR12). Plasma HCV RNA levels were measured using the COBAS TaqMan HCV test (version 2.0), for use with the High Pure System, which has an LLOQ of 25 IU per milliliter.

Outcomes for patients not achieving an SVR12 were recorded as on-treatment virologic failure (VF), post-treatment virologic relapse through post-treatment week 12 or failure due to other non-virologic reasons (e.g., premature discontinuation, adverse event, lost to follow-up, consent withdrawn). HCV RNA was assessed at each study visit and post treatment weeks 4 and 12 (or early post treatment discontinuation).

Key safety parameters that were recorded included dose discontinuations/ modifications due to adverse events (AEs), treatment related serious AEs (SAEs), and laboratory test abnormalities. The onset and end dates, severity and relationship to study drug were recorded for each AE. Patients were questioned and/or examined by the investigator or a qualified designee for evidence of AEs at each treatment visit. The determination of AE severity rested on medical judgment and was made with the appropriate involvement of the investigator or a designated sub-investigator. The severity of AEs, with the exception of laboratory values, was graded according to the WHO grading system. Investigators relied on clinical judgment in assigning severity to abnormal laboratory AEs. Data on all treatment emergent AEs were collected from the start of study drug until 30 d after receipt of the last dose. Clinical laboratory testing was performed at all visits during the treatment period.

The first pre-defined secondary endpoint evaluated the effect of baseline RASs on SVR12. Baseline sampling for RASs was obtained on day 1 for all patients and thereafter only in patients with detectable HCV RNA after previously testing negative (breakthrough) or patients who were undetectable at the end of treatment but had detectable HCV RNA during the follow up period (relapse). Resistance testing was performed by Quest Diagnostics. The patient subgroups evaluated included all RASs and different classes of RASs.

Another pre-defined secondary endpoint evaluated patient reported outcomes, examined via the Short Form–36 version 2 Health Survey (SF36v2), at baseline compared to end of treatment. Patients completed this self-administered questionnaire, which assessed functional health and well-being at baseline and at 12 wk. The results consisted of eight scaled scores, which are the weighted sums of the questions in their section. Scores were aggregated into a mental component summary (MCS) and a physical component summary (PCS); higher scores were indicative of better health.

The final secondary endpoint was to evaluate adherence in patients receiving this treatment regimen. Pills were counted by study personnel at each treatment visit. Treatment compliance was defined as the subject having a total missed pill count of ≤ 20% of the total dispensed pill count over the course of their treatment duration. For patients on RBV, the total dispensed pill count was 840 over 12 wk and 1680 over 24 wk. For patients not on RBV, the total dispensed pill count was 336 over 12 wk and 672 over 24 wk. Patient adherence was reported according to treatment arm.

All patients who consented and received at least one dose of study medication were included in the primary analysis for both efficacy and safety (all-treated population). Descriptive summaries consisted of frequencies and percentages for categorical measures and of the number of patients, mean, standard deviation, median, minimum, and maximum values for continuous measures. Descriptive summaries were presented for select subgroups. Tabular summaries presented included age, sex, and race and other parameters measured at baseline. Since this was a single arm study design, no power statement was calculated.

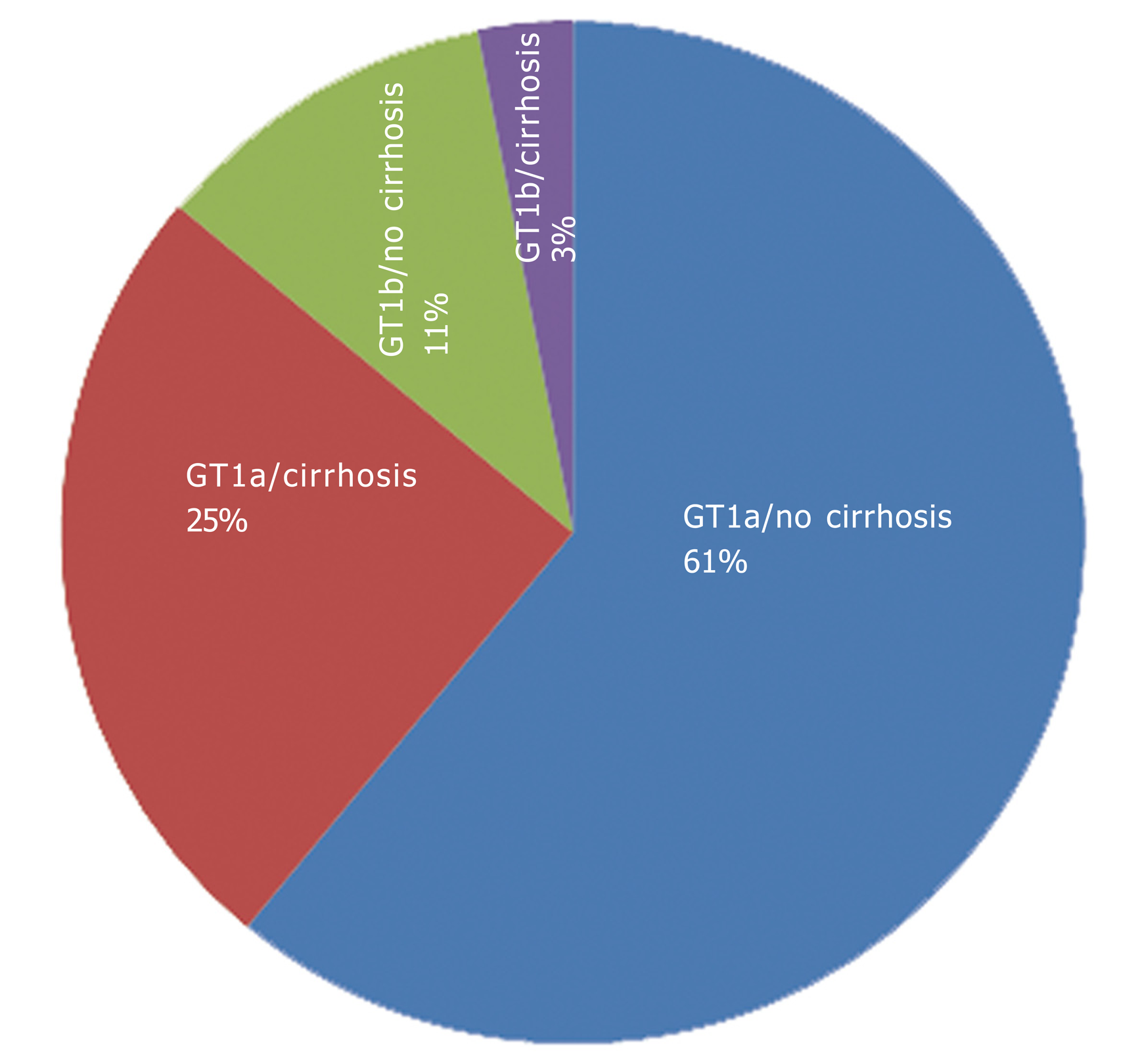

A total of 104 patients were screened and 100 patients were treated with the study drug regimens. The majority of patients (n = 89, 89%) were treated with OBV/PTV/r + DSV + RBV, with 75 (75%) undergoing 12 wk of treatment and 25 (25%) undergoing 24 wk of treatment. The vast majority of patients (86%) were infected with GT1a (Figure 1). Patient characteristics at baseline, including current comorbidities and history of previous HCV treatments are shown in Table 1.

| Characteristic | Patients |

| Age | |

| n | 104 |

| Mean (yr ± SD) | 49.9 ± 10.5 |

| Min, max (yr) | 29.0, 78.0 |

| Median (yr) (IQR) | 51.5 (41.0, 58.2) |

| Gender | |

| n | 104 |

| Female | 46 (44.2) |

| Male | 58 (55.8) |

| Ethnicity | |

| n | 104 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 48 (46.2) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 56 (53.8) |

| Race | |

| n | 104 |

| White | 91 (87.5) |

| Black | 11 (10.6) |

| Unknown | 2 (2) |

| Current comorbidities | |

| n | 104 |

| Hypertension | 46 (44.2) |

| Obesity | 35 (33.7) |

| Cirrhosis, Child-Pugh A | 21 (20.2) |

| Hepatic steatosis | 18 (17.3) |

| Diabetes mellitus, type II | 17(16.3) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 17 (16.3) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 3 (3) |

| Coronary artery disease | 3 (3) |

| Atherosclerosis | 1 (1) |

| Congestive heart failure | 1 (1) |

| HIV | 1 (1) |

| Genotype | |

| n | 100 |

| GT1a | 86 (86) |

| GT1b | 14 (14) |

| Prior HCV treatment | |

| n | 100 |

| IFN | 2 (2) |

| IFN+RBV | 3 (3) |

| PegIFN | 1 (1) |

| PegIFN+RBV | 10 (10) |

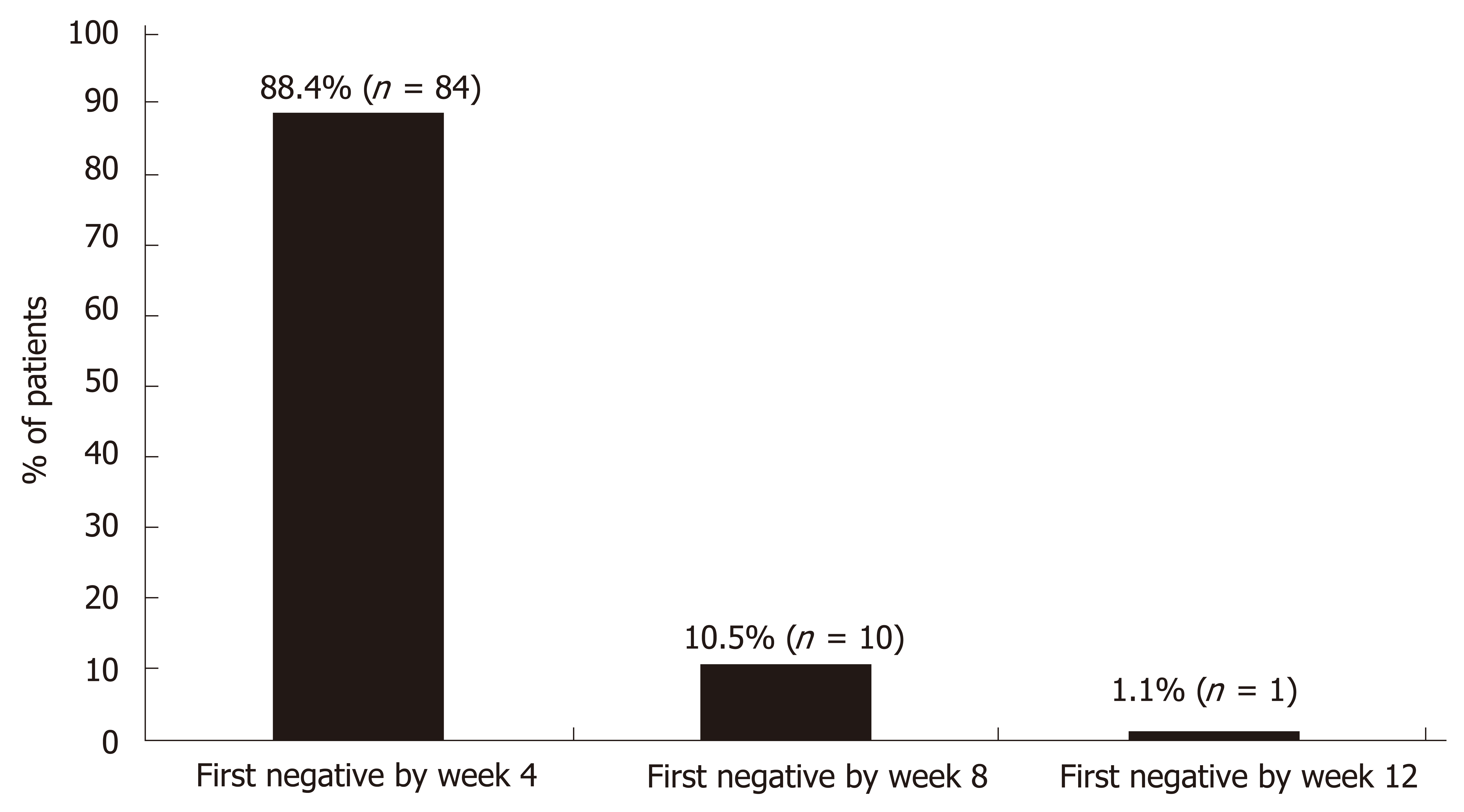

The final date for collection of data was October 3, 2017. One hundred (100) patients received at least one dose of study drug, 96 patients completed follow-up and 95 (95%) achieved SVR12. The HCV RNA results for patients completing treatment with SVR are depicted in Figure 2. The vast majority (88.4%) were undetectable by week 4. Of the 4 patients who exited the study early, 3 were lost to follow-up and 1 was terminated early due to noncompliance. The one patient who completed treatment but did not achieve SVR was a 48-year-old Black male infected with GT1a HCV. He was treatment-naïve, FibroScan® showed no fibrosis (F0) and no baseline RASs were detected. His baseline viral load was 2694796 IU/mL and he was prescribed 12 wk of OBV/PTV/r + DSV + RBV. He had undetectable HCV RNA at treatment week 4 and treatment week 8; however, he missed 6 doses of RBV 8 wk into treatment. He was counseled on medication compliance and didn’t miss any other doses. At end of treatment (week 12), HCV RNA was detected (742 IU/mL) and he was considered a treatment-failure. The patient did not return for his 12-wk follow-up visit.

The number of AEs reported totaled 123. The most common AEs were fatigue (12%), headache (10%), insomnia (9%) and diarrhea (8%) (Table 2). There were no serious AEs or AEs leading to discontinuation reported in this study.

| Most common adverse events | Patients reporting AE (n = 100) |

| Fatigue | 12 (12%) |

| Headache | 10 (10%) |

| Insomnia | 9 (9%) |

| Diarrhea | 8 (8%) |

| Anemia | 6 (6%) |

| Nausea | 6 (6%) |

| Pruritus | 5 (5%) |

| Rash | 4 (4%) |

| Upper respiratory infection | 3 (3%) |

| Urinary tract infection | 3 (3%) |

Sampling for RASs was performed on 99 patients at baseline. There were no detectable mutations in the NS5a or NS5b genes in 88 (88%) and 98 (98%) of these patients, respectively. A probable resistance to OBV was found in one patient (1%) with an NS5a mutation, but no resistance to daclatasvir, elbasvir, ledipasvir or velpatasvir was noted. In addition, there were 4 (4%) cases of possible resistance to OBV, daclatasvir, elbasvir, ledipasvir and velpatasvir. With regard to NS5b RASs, one patient (1%) had a possible resistance to DSV.

Patient reported outcomes were analyzed in patients with both baseline and end of treatment (Week 12 or Week 24) scores (n = 67). These results are portrayed in Table 3. Overall, PCS scores and MCS scores were significantly higher following treatment compared to baseline (P = 0.04 and P = 0.011, respectively). Of the 8 scaled scores, all end of treatment scores were higher compared to baseline, with statistically significant improvement observed for 5 sub-scores (physical, general health, vitality, emotional and mental health).

| End of treatment | Baseline | P value | |

| (n = 67) | (n = 67) | (Paired) | |

| Physical functioning | 45.6 ± 11.3 | 44.4 ± 11.0 | 0.3389 |

| Physical | 45.3 ± 10.8 | 42.2 ± 10.4 | 0.0152 |

| Bodily pain | 46.3 ± 12.0 | 43.9 ± 11.2 | 0.1103 |

| General health | 49.0 ± 10.8 | 44.6 ± 10.5 | 0.0004 |

| Vitality | 50.4 ± 11.9 | 46.0 ± 10.6 | 0.0066 |

| Social functioning | 45.4 ± 11.9 | 42.7 ± 12.1 | 0.0530 |

| Emotional | 45.2 ± 12.1 | 41.8 ± 11.4 | 0.0272 |

| Mental Health | 46.6 ± 12.6 | 44.1 ± 10.4 | 0.0287 |

| Physical component summary | 46.8 ± 10.7 | 44.4 ± 9.1 | 0.0404 |

| Mental component summary | 47.1 ± 13.7 | 43.6 ± 11.6 | 0.0112 |

Treatment compliance was assessed in all 100 patients and 98 (98%; 95% confidence interval, 93 to 99.4) of these patients were considered compliant. The two noncompliant patients were in the OBV/PTV/r + DSV + RBV 12-wk treatment arm. All patients in the OBV/PTV/r + DSV 12-wk arm and the OBV/PTV/r + DSV + RBV 24-wk treatment arm achieved 100% compliance. Four patients terminated the study early (prior to 12 wk) and are included in these data; all 4 met the criteria for treatment compliance while on treatment.

In a real world, all-comers population of HCV GT1 patients, a 12 or 24-wk multi-targeted DAA regimen of OBV/PTV/r + DSV +/- RBV was highly effective with a 95% SVR12 rate. Of the 96 patients who completed follow up, 99% (95/96) achieved SVR12. The presence of baseline RASs had no impact on the ability to achieve SVR12. Furthermore, treatment was associated with a low rate of treatment discontinuation unrelated to AEs. No AEs were considered serious. These efficacy and safety results are comparable to those seen in controlled clinical trials of OBV/PTV/r + DSV +/- RBV[8-11]. Although newer DAA regimens with shorter durations have been recently approved, our data on this older regimen remains important; this regimen is an approved treatment option and is still used in some developing countries.

Our study population was made up of slightly more males than females, which is consistent with the distribution of HCV in the United States[1]. Although there were no Asian patients and a small percentage of Black patients, this study represented an even distribution of Hispanics and non-Hispanics with HCV. HCV data are important in this population. Hispanics are a large and fast-growing minority group in the United States[12] and, according to one study[13], Hispanics infected with HCV are at a significantly higher risk of developing cirrhosis and HCC than non-Hispanic Whites.

Traditionally, individuals with HCV who have comorbidities are considered “hard-to-cure” and are often excluded from controlled clinical trials. The HEARTLAND study sought to enroll these individuals; many of the individuals studied had hypertension (44.2%), obesity (33.7%), Child-Pugh A cirrhosis (20.2%), steatosis (17.3%), type II diabetes mellitus (16.3%) and hyperlipidemia (16.3%). Including these populations in HCV treatment studies is essential. Data has demonstrated that, among patients with HCV, > 99% have at least one comorbidity, with hypertension being one of the most common[14]. In addition, NHANEs investigators predict that the incidence of cirrhosis will peak by the year 2020, affecting 1.76 million HCV-infected individuals in the United States[1]. Finally, metabolic conditions such as steatosis, obesity and diabetes are emerging as independent co-factors of fibrogenesis[15].

Individuals who previously failed HCV treatment are also often disqualified from registration studies or evaluated in separate retreatment studies. Sixteen percent of patients in HEARTLAND were HCV treatment experienced, with the majority (62.5%) previously treated with PegIFN + RBV. The inclusion of these patients did not affect overall SVR rates. This is consistent with what other studies of OBV/PTV/r + DSV +/- RBV have demonstrated: combining antiviral drugs with multiple mechanisms of action is effective regardless of the prior response to PegIFN + RBV[9,16].

In addition to including underrepresented HCV patients, data were collected in the “real world” setting, further demonstrating its applicability in clinical practice. Moreover, results are similar to other published real-world data on this regimen. For example, in a study of 5168 HCV GT1 patients, who were included irrespective of cirrhosis status or prior HCV treatment experience, real world SVR12 rates were consistently high (94 to 99%) for the OBV/PTV/r + DSV +/- RBV regimen[17]. Another study performed in Taiwan showed SVR12 rates of 98% and good tolerability in patients administered this regimen[18].

The data generated from the secondary analyses performed in this study are also consistent with published reports. With regard to resistance testing, according to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) HCV Guidance, Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C, a subset of patients with HCV will have viral variants harboring substitutions associated with resistance to DAAs, especially with NS5A inhibitor-containing regimens. This may negatively impact treatment response[19]. In HEARTLAND, SVR rates approached 100% despite the presence of baseline NS5A and NS5B RASs in 12% and 2% of patients, respectively. This reinforces what is stated in the AASLD HCV guidance: the magnitude of the negative impact of RASs varies according to many factors and RAS testing alone will not dictate optimal DAA regimen selection[19].

Another secondary analysis was the effect of OBV/PTV/r + DSV +/- RBV on patient reported outcomes. Such outcome assessments provide patients’ perspective on the impact of treatment on daily life and work. HEARTLAND demonstrated, via data collected from the SF36v2 short form, that OBV/PTV/r + DSV +/- RBV significantly improved patient reported outcomes for total physical and mental components. The MALACHITE-I and MALACHITE-II controlled clinical studies in HCV G1 patients evaluated the same secondary endpoints using a similar method and demonstrated matching trends. Overall, patients treated with OBV/PTV/r + DSV +/- RBV have better mental and physical health following HCV treatment[20].

Finally, patient adherence was addressed in HEARTLAND. Adherence is important when successfully treating HCV and becomes even more critical in the real-world setting. Often, efficacy rates reported from clinical trials are substantially reduced when drugs are approved and used in clinical practice. The reasons for this are multifactorial and can be due to side effects, complexity of the regimen and/or other patient-related factors[21]. In our study, we demonstrated excellent adherence rates (98% treatment compliance) in the real-world setting using a complex regimen. This study was designed to enroll approximately 100 patients with baseline factors that may have limited their ability to enroll in registration trials including 28% with cirrhosis. The safety and efficacy results reported in this study are impressive and comparable to those reported in registration trials.

In conclusion, the all oral, DAA regimen containing OBV/PTV/r + DSV +/- RBV was associated with a 99% SVR at post-treatment week 12 in GT1-infected patients, with and without compensated cirrhosis.

The hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a prevalent virus that, if left untreated, leads to chronic liver disease and, ultimately, death. The new era of direct acting antiviral (DAA) treatment regimens has the potential to cure the virus [i.e., achieve sustained virologic response (SVR)] in the majority of patients. The HCV NS5A inhibitor ombitasvir (OBV), HCV NS4/4A protease inhibitor paritaprevir (PTV), the CYP3A inhibitor ritonavir and the non-nucleoside NS5B polymerase inhibitor dasabuvir (DSV) (OBV/PTV/r + DSV) with or without ribavirin (RBV) is a DAA regimen that achieves SVR rates as high as 99% in HCV genotype 1 (GT1) patients in controlled clinical studies. However, there are patients who are considered “hard to cure” that are traditionally excluded from registration trials due to rigorous study inclusion criteria, presence of comorbidities and previous treatment failures. This phase 4, open label study evaluated the safety and efficacy of OBV/PTV/r + DSV +/- RBV in a real-world clinical setting in patients who have historically been excluded from clinical trials. This study is completed.

Controlled clinical studies demonstrate 99% SVR rates in patients with HCV GT1, however, many patients in these studies do not meet the inclusion criteria for these studies. In a real world population of HCV patients, many have comorbidities or history of previous HCV treatment failures. We sought to examine the efficacy and safety of OBV/PTV/r + DSV +/- RBV in real world HCV patients who are generally underrepresented in clinical trials. This study also examined patient quality of life, dosing adherence and whether resistance-associated substitutions (RASs) impact achievement of SVR, which are all real world issues encountered in HCV patients. The results of this study will determine if controlled clinical trial results can be expected in everyday HCV patients seen in clinical practice.

The primary objective of this study was to examine the efficacy and safety of OBV/PTV/r + DSV +/- RBV in real world HCV patients generally underrepresented in clinical trials. This study found that this treatment regimen was highly effective and no adverse events were considered serious; these results are comparable to those seen in controlled clinical trials with this treatment regimen. Therefore, including patients with comorbidities or a history of previous HCV treatment(s) did not affect the results. According to this one study, the results demonstrated in controlled clinical trials involving OBV/PTV/r + DSV +/- RBV can be applied to everyday HCV patients seen in clinical practice.

Patients were ≥ 18 years old and chronically infected with HCV GT1 (GT1a, GT1b or GT1a/1b). Patients were treatment-naïve or previously failed a regimen including pegylated interferon/RBV +/- telaprevir, boceprevir, or simeprevir. One hundred patients were treated with the study drug regimen, which was administered for 12 or 24 wk +/- RBV according to GT1 subtype and presence/absence of cirrhosis. Patients were evaluated every 4 wk from treatment day 1 and at 4 and 12 wk after end-of-treatment.

Many of the patients studied had comorbidities (44.2% hypertensive, 33.7% obese, 20.2% cirrhotic) and 16% previously failed HCV treatment. Ninety-six patients completed study follow-up and 99% achieved 12-wk sustained virologic response. The majority (88.4%) of patients had undetectable HCV RNA by week 4. The most common adverse events were fatigue (12%), headache (10%), insomnia (9%) and diarrhea (8%); none led to treatment discontinuation. Physical and mental patient reported outcomes scores significantly improved after treatment. Almost all (98%) patients were treatment compliant.

In an all-comers HCV GT1 population, 12 or 24-wk of OBV/PTV/r + DSV +/- RBV is highly effective and tolerable and results in better mental and physical health following treatment.

Results of he approved use of the OBV/PTV/r + DSV +/- RBV regimen in HCV GT1 patients in clinical practice can potential mirror results obtained in controlled clinical trials. The availability of real world data on approved HCV treatment regimens is extremely useful in clinical practice. Newer DAA regimens with shorter treatment durations have been recently approved. These regimens should also be evaluated in the real world population of HCV patients. Future clinical studies need to evaluate the efficacy and safety of these newer DAA regimens in real world patients. Patients with comorbidities and those who have had previous HCV treatment failures should be included in these studies. In addition, secondary measures should include physical and mental outcomes, the affects of RASs and adherence to the newer regimens.

Data management was performed by John Sendajo of Texas Liver Institute. Statistical analyses were performed by Marc Schwartz of MS Biostatistics, LLC. Writing support was provided by Rachel E. Bejarano, PharmD of RB Scientific Services, LLC and Lisa D. Pedicone, PhD of Cerulean Consulting, LLC.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kai K, Karatapanis S, Khuroo MS S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A E-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Armstrong GL, Wasley A, Simard EP, McQuillan GM, Kuhnert WL, Alter MJ. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1999 through 2002. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:705-714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1484] [Cited by in RCA: 1467] [Article Influence: 77.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Afdhal NH. The natural history of hepatitis C. Semin Liver Dis. 2004;24 Suppl 2:3-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Morgan TR, Ghany MG, Kim HY, Snow KK, Shiffman ML, De Santo JL, Lee WM, Di Bisceglie AM, Bonkovsky HL, Dienstag JL, Morishima C, Lindsay KL, Lok AS; HALT-C Trial Group. Outcome of sustained virological responders with histologically advanced chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2010;52:833-844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 392] [Cited by in RCA: 376] [Article Influence: 25.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Morgan RL, Baack B, Smith BD, Yartel A, Pitasi M, Falck-Ytter Y. Eradication of hepatitis C virus infection and the development of hepatocellular carcinoma: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:329-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 631] [Cited by in RCA: 653] [Article Influence: 54.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Charlton MR, Burns JM, Pedersen RA, Watt KD, Heimbach JK, Dierkhising RA. Frequency and outcomes of liver transplantation for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1249-1253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 835] [Cited by in RCA: 855] [Article Influence: 61.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yang JD, Larson JJ, Watt KD, Allen AM, Wiesner RH, Gores GJ, Roberts LR, Heimbach JA, Leise MD. Hepatocellular Carcinoma Is the Most Common Indication for Liver Transplantation and Placement on the Waitlist in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:767-775.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (35)] |

| 7. | American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and Infectious Diseases Society of America. HCV Guidance: Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C [Internet]. Available from: http://www.hcvguidelines.org/. |

| 8. | Feld JJ, Kowdley KV, Coakley E, Sigal S, Nelson DR, Crawford D, Weiland O, Aguilar H, Xiong J, Pilot-Matias T, DaSilva-Tillmann B, Larsen L, Podsadecki T, Bernstein B. Treatment of HCV with ABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with ribavirin. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1594-1603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 681] [Cited by in RCA: 656] [Article Influence: 59.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zeuzem S, Jacobson IM, Baykal T, Marinho RT, Poordad F, Bourlière M, Sulkowski MS, Wedemeyer H, Tam E, Desmond P, Jensen DM, Di Bisceglie AM, Varunok P, Hassanein T, Xiong J, Pilot-Matias T, DaSilva-Tillmann B, Larsen L, Podsadecki T, Bernstein B. Retreatment of HCV with ABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with ribavirin. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1604-1614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 452] [Cited by in RCA: 445] [Article Influence: 40.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Feld JJ, Moreno C, Trinh R, Tam E, Bourgeois S, Horsmans Y, Elkhashab M, Bernstein DE, Younes Z, Reindollar RW, Larsen L, Fu B, Howieson K, Polepally AR, Pangerl A, Shulman NS, Poordad F. Sustained virologic response of 100% in HCV genotype 1b patients with cirrhosis receiving ombitasvir/paritaprevir/r and dasabuvir for 12weeks. J Hepatol. 2016;64:301-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Andreone P, Colombo MG, Enejosa JV, Koksal I, Ferenci P, Maieron A, Müllhaupt B, Horsmans Y, Weiland O, Reesink HW, Rodrigues L, Hu YB, Podsadecki T, Bernstein B. ABT-450, ritonavir, ombitasvir, and dasabuvir achieves 97% and 100% sustained virologic response with or without ribavirin in treatment-experienced patients with HCV genotype 1b infection. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:359-365.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 289] [Cited by in RCA: 304] [Article Influence: 27.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hispanic Heritage Month 2017—Census Bureau. Available from: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/facts-for-features/2017/hispanic-heritage.html. |

| 13. | El-Serag HB, Kramer J, Duan Z, Kanwal F. Racial differences in the progression to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in HCV-infected veterans. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1427-1435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Louie KS, St Laurent S, Forssen UM, Mundy LM, Pimenta JM. The high comorbidity burden of the hepatitis C virus infected population in the United States. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Massard J, Ratziu V, Thabut D, Moussalli J, Lebray P, Benhamou Y, Poynard T. Natural history and predictors of disease severity in chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2006;44:S19-S24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kowdley KV, Lawitz E, Poordad F, Cohen DE, Nelson DR, Zeuzem S, Everson GT, Kwo P, Foster GR, Sulkowski MS, Xie W, Pilot-Matias T, Liossis G, Larsen L, Khatri A, Podsadecki T, Bernstein B. Phase 2b trial of interferon-free therapy for hepatitis C virus genotype 1. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:222-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wedemeyer H, Craxí A, Zuckerman E, Dieterich D, Flisiak R, Roberts SK, Pangerl A, Zhang Z, Martinez M, Bao Y, Calleja JL. Real-world effectiveness of ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir±dasabuvir±ribavirin in patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 or 4 infection: A meta-analysis. J Viral Hepat. 2017;24:936-943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Liu CH, Liu CJ, Su TH, Yang HC, Hong CM, Tseng TC, Chen PJ, Chen DS, Kao JH. Real-world effectiveness and safety of paritaprevir/ritonavir, ombitasvir, and dasabuvir with or without ribavirin for patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1b infection in Taiwan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;33:710-717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and Infectious Diseases Society of America. HCV Resistance Primer. Available from: https://www.hcvguidelines.org/evaluate/resistance. |

| 20. | Dore GJ, Conway B, Luo Y, Janczewska E, Knysz B, Liu Y, Streinu-Cercel A, Caruntu FA, Curescu M, Skoien R, Ghesquiere W, Mazur W, Soza A, Fuster F, Greenbloom S, Motoc A, Arama V, Shaw D, Tornai I, Sasadeusz J, Dalgard O, Sullivan D, Liu X, Kapoor M, Campbell A, Podsadecki T. Efficacy and safety of ombitasvir/paritaprevir/r and dasabuvir compared to IFN-containing regimens in genotype 1 HCV patients: The MALACHITE-I/II trials. J Hepatol. 2016;64:19-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Henry L, Nader F, Younossi Y, Hunt S. Adherence to treatment of chronic hepatitis C: from interferon containing regimens to interferon and ribavirin free regimens. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e4151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |