Published online Mar 21, 2019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i11.1387

Peer-review started: December 13, 2018

First decision: January 30, 2019

Revised: February 6, 2019

Accepted: February 15, 2019

Article in press: February 15, 2019

Published online: March 21, 2019

Processing time: 97 Days and 20.2 Hours

Endoscopic papillectomy (EP) for benign ampullary neoplasms could be a less-invasive alternative to pancreatoduodenectomy (PD). There are some problems and limitations with EP. The post-EP resection margins of ampullary tumors are often positive or uncertain because of the burning effect of EP. The clinical outcomes of resected margin positive or uncertain cases after EP remain unknown.

To investigate the clinical outcomes of resected margin positive or uncertain cases after EP.

Between January 2007 and October 2018, all patients with ampullary tumors who underwent EP at Kobe University Hospital were included in this study. The indications for EP were as follows: adenoma, as determined by preoperative endoscopic biopsy, without bile/pancreatic duct extension, according to endoscopic ultrasound or intraductal ultrasound. The clinical outcomes of resected margin positive or uncertain cases after EP were retrospectively investigated.

Of the 45 patients, 29 were male, and 16 were female. The mean age of the patients was 65 years old. Forty-one patients (89.5%) underwent en bloc resection, and 4 patients (10.5%) underwent piecemeal resection. After EP, 33 tumors were histopathologically diagnosed as adenoma, and 12 were diagnosed as adenocarcinoma. The resected margins were positive or uncertain in 24 patients (53.3%). Of these cases, 15 and 9 were diagnosed as adenoma and adenocarcinoma, respectively. Follow-up observation was selected for all adenomas and 5 adenocarcinomas. In the remaining 4 adenocarcinoma cases, additional PD was performed. Additional PD was performed in 4 cases, and residual carcinoma was found after the additional PD in 1 of these cases. In the follow-up period, local tumor recurrence was detected in 3 cases. Two of these cases involved primary EP-diagnosed adenoma. The recurrent tumors were also adenomas detected by biopsy. The remaining case involved primary EP-diagnosed adenocarcinoma. The recurrent tumor was also an adenocarcinoma. All of the recurrent tumors were successfully treated with argon plasma coagulation (APC). There was no local or lymph node recurrence after the APC. The post-APC follow-up periods lasted for 57.1 to 133.8 mo. No ampullary tumor-related deaths occurred in all patients.

Resected margin positive or uncertain cases after EP could be managed by endoscopic treatment including APC, even in cases of adenocarcinoma. EP could become an effective less-invasive first-line treatment for early stage ampullary tumors.

Core tip: In this study, we investigated the clinical outcomes of resected margin positive or uncertain cases after endoscopic papillectomy (EP). All of the recurrent tumors were successfully treated with argon plasma coagulation, even in cases of adenocarcinoma. There was no local or lymph node recurrence after the argon plasma coagulation. No ampullary tumor-related deaths occurred in all patients. In conclusion, resected margin positive or uncertain cases after EP could be managed by endoscopic treatment.

- Citation: Sakai A, Tsujimae M, Masuda A, Iemoto T, Ashina S, Yamakawa K, Tanaka T, Tanaka S, Yamada Y, Nakano R, Sato Y, Kurosawa M, Ikegawa T, Fujigaki S, Kobayashi T, Shiomi H, Arisaka Y, Itoh T, Kodama Y. Clinical outcomes of ampullary neoplasms in resected margin positive or uncertain cases after endoscopic papillectomy. World J Gastroenterol 2019; 25(11): 1387-1397

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v25/i11/1387.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i11.1387

Endoscopic papillectomy (EP) for benign ampullary neoplasms could be a less-invasive alternative to pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) because PD might be an excessively invasive treatment for benign neoplasms[1,2]. The current standard treatment for ampullary tumor is PD, which is still associated with a high morbidity rate despite a recent reduction in the mortality rate to less than 5%[3,4]. On the other hand, the mortality after EP has been reported by high volume centers to be 0.4%. The overall complication rate of EP was reported between 8% and 35%, and the most common complications are pancreatitis (5%15%) and bleeding (2%16%). Most episodes of bleeding can be controlled by endoscopic hemostasis, and most episodes of pancreatitis are mild and resolved with conservative treatment[5]. Surgical ampullectomy (SA) is another alternative to PD. Ceppa et al[6] showed that EP was found to have equivalent efficacy when compared with SA. Moreover, EP had lower morbidity and identical mortality.

There are some problems and limitations with EP. The preoperative detection of tumor extension into a bile duct or the pancreatic duct is sometimes technically difficult, although the diagnostic ability of imaging studies, such as endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS), has recently markedly improved[7,8]. In addition, the pathological evaluation of the margins of resected ampullary tumor specimens is often difficult because of the burning effect of EP[9]. Therefore, we sometimes experience resected margin positive or uncertain cases and the management of those cases might be important clinical issue on preforming this endoscopic treatment.

Recently, some studies have indicated that EP might be a useful treatment for early stage ampullary carcinoma with T1, in which the tumor is limited to the sphincter of Oddi[10]. In cases involving T2, in which the tumor has invaded the duodenal wall, additional surgery is recommended because the frequency of lymph node metastasis was reported to range from 24%-45% in such cases[11-14]. Furthermore, Yamamoto et al[15] reported that there was no lymphovascular invasion or lymph node metastasis in any T1a cases, whereas one of four T1b cases exhibited lymphovascular invasion. Therefore, in cases of early stage ampullary carcinoma, distinguishing between T1a and T1b during preoperative diagnostic examinations might be extremely important for ensuring that the indications for EP are appropriate. However, unfortunately, there are no diagnostic tools for clearly detecting tumor invasion into the sphincter of Oddi. The identification of the sphincter of Oddi using EUS or intraductal ultrasound (IDUS) is still technically difficult in many cases. For these reasons, EP for early stage ampullary carcinoma is still challenging, and its indications might be restrictive.

Moreover, the post-EP resection margins of ampullary tumors are often positive or uncertain because of the burning effect of EP. The clinical outcomes of resected margin positive or uncertain cases after EP remains unknown. Decisions regarding the treatment course in such cases might differ among institutions and/or depend on each patient’s condition. Therefore, in this study we investigated the clinical outcomes of ampullary neoplasms encountered at our hospital, including ampullary carcinomas that were diagnosed based on pathological evaluations of resected specimens, that exhibited positive or uncertain margins after EP.

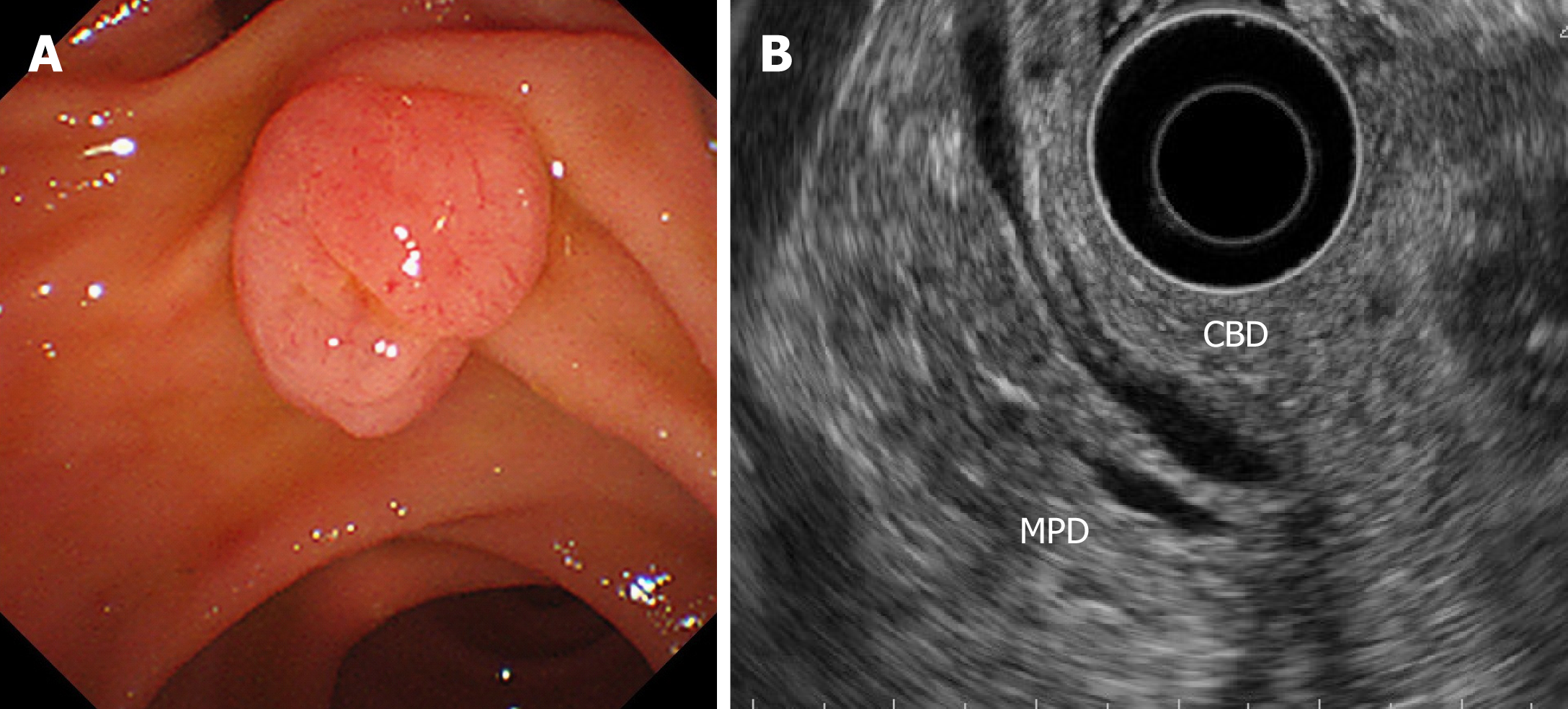

All patients with ampullary tumors who underwent EP at Kobe University Hospital between January 2007 and October 2018 were included in this study. Tumor staging and intraductal involvement were evaluated using computed tomography (CT) and EUS for all patients. IDUS was attempted for cases that were difficult to diagnose intraductal extension by EUS, because of the risk of pancreatitis. The main indication for EP was adenoma, as determined by a preoperative biopsy examination, without bile/pancreatic duct extension, according to EUS and/or IDUS (Figure 1). In the cases with evidence of ampullary carcinoma by the preoperative biopsy, PD was recommended. In some cases, such as those involving super-elderly patients or patients in a poor general condition, EP was performed when T2 invasion was not detected by preoperative imaging studies. Preoperative biopsy diagnosed as adenocarcinoma was only 4 patients in this study. In these cases, they were unfit for surgery because 1 patient was super-elderly (85 years old), and 3 patients were poor general condition with severe comorbidity. The clinical outcomes of each EP cases were retrospectively investigated. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the ethical committee at Kobe University School of Medicine before the study (No. 170057). This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the consolidated Good Clinical Practice guidelines. All authors had access to the study data, and they all reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

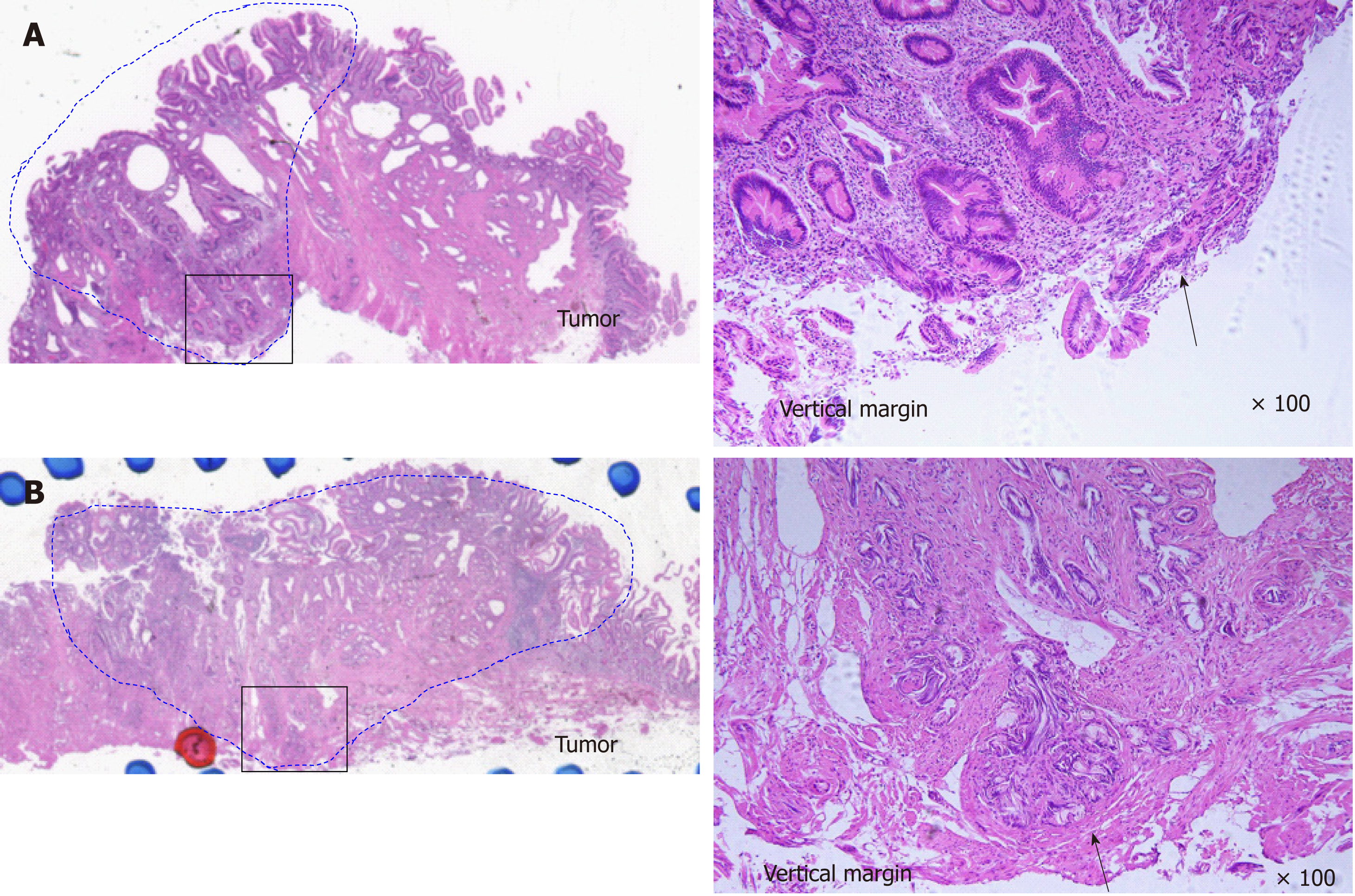

EP was carried out with a standard polypectomy snare using a blended electrosurgical current. Even though it became piecemeal resection because of its size, the tumor was completely resected endoscopically in all cases. We tried to insert both bile duct and pancreatic duct stents after the EP procedure. Post-EP bleeding was defined as hematemesis and/or melena or a > 2 g/dL decrease in hemoglobin level (bleeding requiring hemostasis). Immediate bleeding was not defined as post-EP bleeding. Post-EP pancreatitis was defined as an increase in serum amylase/lipase to > 3 times the upper limit of normal, along with typical pancreatic-type pain. Experienced pathologists examined the resected specimens. The final depth of cancer invasion was recorded according to the Classification of Biliary Tract Carcinoma developed by the Japanese Society of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery as follows[16]: carcinoma in situ, tumors limited to the mucosa, tumors limited to the sphincter of Oddi, and tumors that had invaded the duodenal wall were defined as Tis, T1a, T1b, and T2, respectively (Table 1). Horizontal margins (HM) and vertical margins (VM) were assessed as follows: positive (Figure 2A): involvement of the margin; uncertain (Figure 2B): involvement of the margin cannot be assessed; negative: margins were tumor-free. After examining the resected specimens, additional PD was recommended in the cases of adenocarcinoma. However, in the cases in which additional PD could not be performed based on the patient’s wishes or condition, we chose to perform palliative endoscopic treatment or medical follow-up. In all cases of adenoma, medical follow-up was recommended, even though the resected tumor exhibited a positive or uncertain margin after EP.

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ |

| T1a | Tumor limited to mucosa |

| T1b | Tumor limited to sphincter of Oddi |

| T2 | Tumor invades duodenal wall |

| T3a | Tumor invades pancreas within 5 mm in depth |

| T3b | Tumor invades pancreas beyond 5 mm in depth |

| T4 | Tumor invades peripancreatic soft tissues, or other adjacent organs or structures |

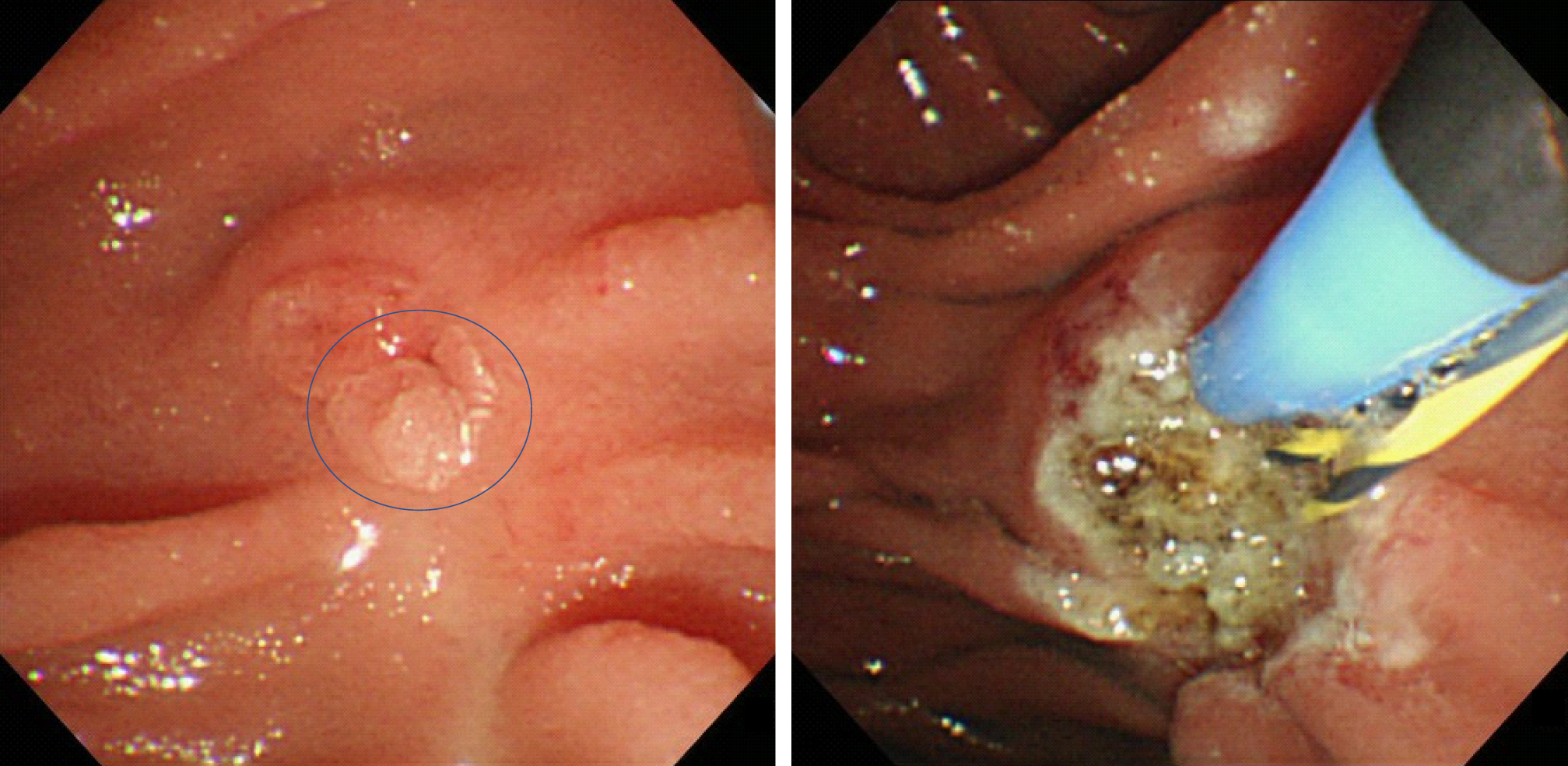

The first follow-up session was scheduled for 3 mo after EP. Then, follow-up examinations were scheduled every 3 mo to 6 mo for 1 year, and yearly thereafter for 5 years. The follow-up examinations included blood tests (for transaminase, pancreatic enzyme, and tumor markers), duodenoscopy with biopsies, and contrast-enhanced CT scans. When a polypoid lesion that was suspected to be a recurrent tumor was detected on follow-up duodenoscopy, an endoscopic biopsy was performed. Additional management strategies, such as argon plasma coagulation (APC) or PD, were considered when the biopsy demonstrated a tumorous lesion. PD was recommended for all cases of recurrent cancer. However, patients who refused or were unfit for PD were considered for APC. APC was recommended for adenomas (Figure 3).

The characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 2. Of the 45 patients, 29 were male, and 16 were female. The mean age of the patients was 65.0 years old (65.0 ± 11.5). Six patients were over 80 years old (13.3%). Forty-one tumors (91.1%) were treated with en bloc resection, and 4 (8.9%) tumors were treated with piecemeal resection. Prophylactic both pancreatic and biliary stent was placed in 33 (73.3%) patients, only pancreatic stent was placed in 7 (15.6%) patients, and only biliary stent was placed in 4 (8.9%) patients, there was no stent placement in 1 (2.2%) case. Complications occurred in 42.2% of all patients. Hemorrhage occurred in 9 patients (20.0%), and pancreatitis occurred in 13 patients (28.9%). One of 9 post-EP hemorrhage cases was severe bleeding that needed transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE). One of 13 post-EP pancreatitis cases was severe acute pancreatitis. Prophylactic pancreatic stent was placed in all post-EP pancreatitis patients. There were no complication related deaths. The mean hospital stay was 15.4 d. After EP, 33 (73.3%) tumors were histopathologically diagnosed as adenomas, and 12 (26.7%) were diagnosed as adenocarcinomas. The diagnostic accuracy of preoperative biopsy was 68.9% (31/45), with underestimated diagnosis in 2.2% (1/45) (Table 3). The resected margins were positive in 12 cases, uncertain in 12 cases, and negative in 21 cases. The HM were positive in 9 cases and uncertain in 10 cases. The VM were positive in 5 cases and uncertain in 9 cases. The median duration of the follow-up period was 27.1 mo (range: 3.0-133.4).

| Number of all EP cases | 45 |

| Male/female | 29/16 |

| Age (yr, mean ± SD) | 65.0 ± 11.5 |

| Tumor size (mm, mean ± SD) | 21.1 ± 6.2 |

| En-bloc resection/piecemeal resection | 41/4 |

| Stent placement | |

| Both/pancreatic/biliary/none | 33/7/4/1 |

| Complications of EP | |

| Post-EP bleeding | 9 (20.0%) |

| Post-EP pancreatitis | 13 (28.9%) |

| Hospital stay (d, mean ± SD) | 15.4 ± 8.5 |

| Pathological diagnosis | |

| Adenoma/adenocarcinoma | 33/12 |

| Pathological evaluation of resected margin | |

| Positive/uncertain/negative | 12/12/21 |

| Horizontal margin | |

| Positive/uncertain | 9/10 |

| Vertical margin | |

| Positive/uncertain | 5/9 |

| Median observation period (mo, range) | 27.1 (3.0-133.4) |

| Preoperative biopsy | Number | Final pathological diagnosis | |

| Adenoma | Adenocarcinoma | ||

| Adenoma | 30 | 28 | 2 |

| Borderline | 11 | 4 | 7 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 4 | 1 | 3 |

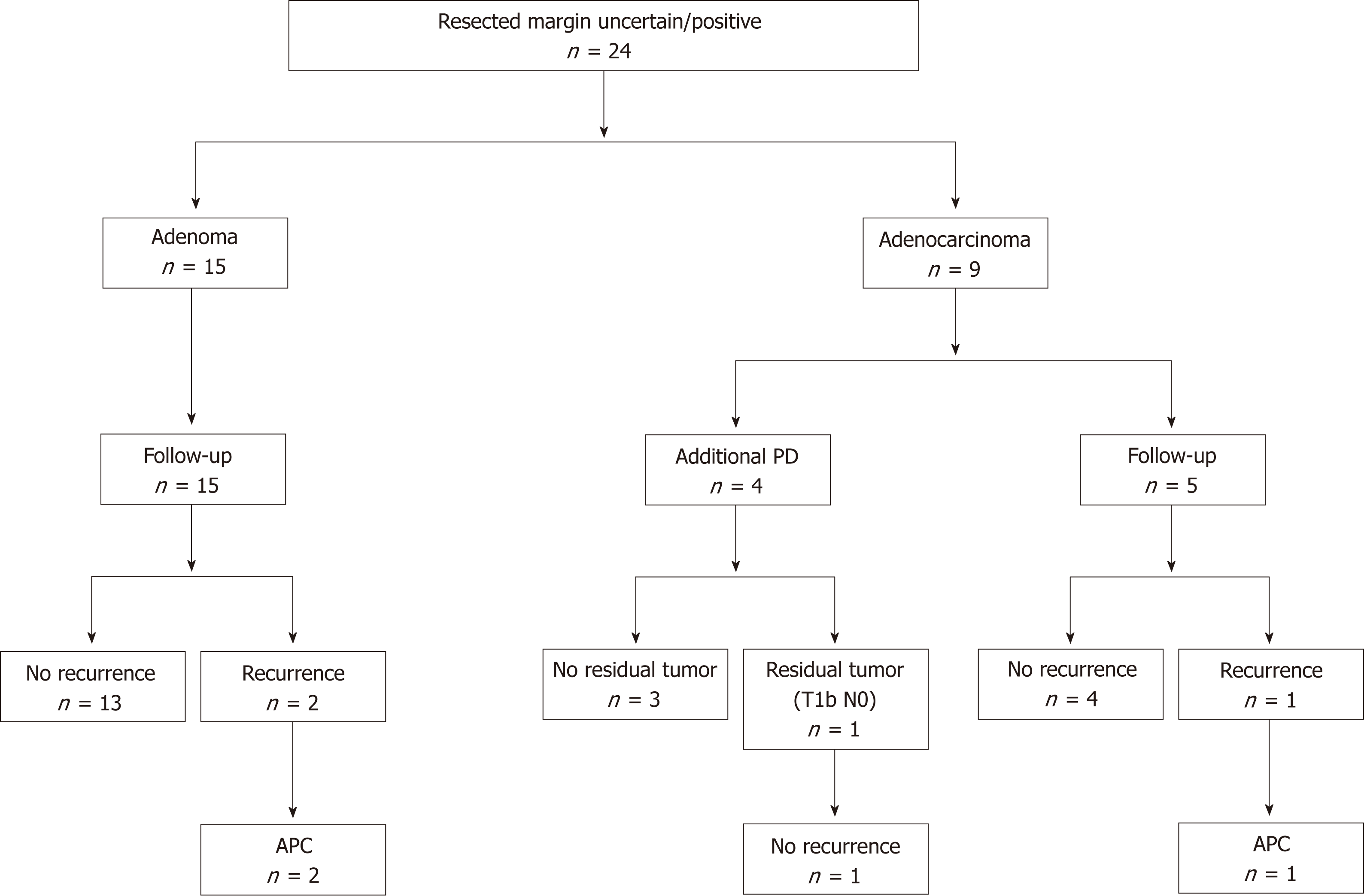

Clinical outcomes of resected margin positive or uncertain cases are shown in Figure 4. The frequency of positive or uncertain margins after EP was 53.3% (24/45). Among these cases, 15 and 9 were diagnosed as adenoma and adenocarcinoma, respectively. In all cases of adenoma and 5 cases of adenocarcinoma, follow-up observation was selected. In 4 cases of adenocarcinoma, additional PD was performed. No residual tumors were found after additional PD in 3 cases, whereas residual carcinoma was detected after additional PD in the remaining case. In the latter case, the depth of the resected specimen after EP was suspected to be T1b, and the final pathological stage after PD was T1b without lymph node metastasis. In the follow-up period, local tumor recurrence was observed in 3 cases. In 2 of these cases, primary adenomas were diagnosed based on EP. After the EP, recurrent adenomas were diagnosed based on biopsy examinations. In the remaining case, a primary adenocarcinoma was diagnosed based on EP, and the recurrent tumor was also an adenocarcinoma. All of the recurrent tumors were successfully treated with APC. No local or lymph node recurrence was detected during the subsequent follow-up period (duration: 57.1 mo to 133.8 mo). No ampullary tumor-related deaths occurred in all patients.

The clinical outcomes of the resected margin-negative cases are shown in Figure 5. Among the cases that exhibited negative margins after EP, 18 cases were diagnosed as adenoma, 2 were diagnosed as Tis, and 1 was diagnosed as T1a. Follow-up observation was selected in all patients. In 1 of the cases of adenoma, local recurrence was detected. The recurrent tumor was also an adenoma and was detected during a biopsy examination. The recurrent tumor was treated with APC, and no local recurrence was detected during the subsequent follow-up period (duration: 71.0 mo).

The clinical data of the cases involving recurrence after EP are shown in Table 4. There were 4 cases of recurrence after EP. In 20 follow-up cases of resected margin positive or uncertain cases, local recurrence was detected in 3 cases. In 21 resected margin negative cases, local recurrence was detected in 1 case. There was no significant difference in the local recurrence between resected margin positive /uncertain and negative cases (P = 0.34, 2-sided Fisher’s exact test). In the local recurrent cases, 3 of the primary lesions were diagnosed as adenomas after EP, and 1 was diagnosed as an adenocarcinoma. There was no significant difference in the local recurrence between adenomas and adenocarcinomas (P = 0.99, 2-sided Fisher’s exact test). The primary tumors ranged in size from 17 mm to 25 mm. The HM were positive and the VM were uncertain in 2 cases, the HM were positive and the VM were negative in 1 case, and both margins were negative in 1 case. There is no difference in the post-EP recurrence between the positive or uncertain HM and positive or uncertain VM. The duration of the period from EP to recurrence ranged from 1.0 mo to 6.3 mo. All of these cases were successfully treated with APC. The post-APC follow-up period lasted for 56.6 mo to 133.4 mo.

| Age | Sex | Preoperative diagnosis | Final diagnosis | Size (mm) | Resection margin | Duration to recurrence (mo) | Additional treatment | Follow up periods after APC (mo) |

| 75 | Male | Adenoma | Adenoma | 25 | HM (+), VM (X) | 1.0 | APC | 75.9 |

| 60 | Female | Adenoma | Adenoma | 17 | HM (+), VM (X) | 5.0 | APC | 133.4 |

| 73 | Male | Borderline | Adenocarcinoma | 22 | HM (+), VM (-) | 1.2 | APC | 56.6 |

| 74 | Female | Adenoma | Adenoma | n/d | HM (-), VM (-) | 6.3 | APC | 71.0 |

In this study, we investigated the clinical outcome of resected margin positive or uncertain cases after EP. EP for benign ampullary tumors is widely accepted as a less-invasive alternative to surgery. However, the pathological evaluation of resected margins was often difficult in the present study because of the burning effect of EP. Moreover, in some cases carcinoma was identified during post-EP pathological evaluations. There is no consistent evidence about the management of ampullary tumors that display positive or uncertain margins after EP.

The current study included 45 patients who underwent EP for ampullary tumors, and 24 (53.3%) of these cases exhibited positive or uncertain margins after EP. In previous studies, the frequency of incomplete EP-based resection varied from 10.6%-57.1%[1,9,10,15,17]. However, the definitions of incomplete resection differed among these studies. In our study, the frequency of a positive or uncertain margin among resected ampullary tumors was relatively high. This was probably due to equivocal findings caused by the burning effect of EP producing uncertain diagnoses because there is a tendency for the pathologists at our hospital to avoid underestimation.

The recurrence rate of ampullary tumors after EP was reported to range from 10%-33% in previous studies[18-21]. In our study, additional PD was performed in 4 of the 24 cases in which positive or uncertain margins were detected after the resection procedure. Of these 4 cases, a residual tumor was only found in 1 case. In the remaining 20 cases, follow-up observation was selected, and local tumor recurrence occurred in 15% (3/20) of these cases. Our results are similar to those of previous studies, despite the fact that our study included cases that exhibited positive or uncertain margins after EP. Among the cases that exhibited negative margins after EP, local tumor recurrence was found in 1 of 21 cases. In the literature of Ridtitid et al[21], among patients with ampullary adenoma who had complete resection (n = 107), 16 patients (15%) developed recurrence up to 65 mo after resection. These results suggest that evaluating the margins of resected ampullary tumors after EP is sometimes difficult. Therefore, careful follow-up examinations are recommended after EP in all cases of ampullary tumors. Established recommendation of follow-up protocol after EP has not been published. This point should be addressed in the future investigation.

APC is a type of non-contact thermal ablation in which a high-frequency current is applied to the target lesion, and it is widely used for the treatment of endoscopic hemostasis or additional treatment after endoscopic resection. APC has been reported to be useful for recurrent ampullary tumors that arise after EP[1,9,15,17]. In our study, all of the recurrent tumors were successfully treated with APC, and there was no local or lymph node recurrence after APC (duration of the follow-up period: 56.6 mo to 133.4 mo). This indicates that APC is a reliable and feasible way of treating locally recurrent ampullary tumors that arise after EP. On the other hand, Nam et al[22] reported usefulness of APC subsequent to EP. In this literature, they concluded additional APC during EP might have a beneficial effect by decreasing bleeding rate without harmful effects but not have an effect of decreasing tumor recurrence.

Pancreatitis is the most common problematic complication of EP. Currently, several studies have shown that placement of a prophylactic pancreatic stent after EP reduces the risk of pancreatitis. A prospective, randomized, controlled trial showed that pancreatic duct stenting after EP significantly decreased the rate of post-EP pancreatitis[23]. However, whether or not post EP pancreatic stenting can alleviate the rate of pancreatitis is still controversial. Some studies have shown no statistically significant benefit by prophylactic placement of a pancreatic stent during EP. In this study, post-EP pancreatitis occurred in 13 patients (28.9%). Prophylactic pancreatic stent had been placed in all post-EP pancreatitis patients. Further prospective controlled studies are required to evaluate the efficacy of prophylactic pancreatic stenting after EP for prevention of post-EP pancreatitis.

The present study had some limitations. First, it was affected by selection bias due to its retrospective nature. However, before performing EP we intensively examined the patients for bile/pancreatic duct invasion using EUS or IDUS. This resulted in good clinical courses being achieved, even in cases that exhibited positive or uncertain margins after EP. Second, the sample size was too small to allow the results to be generalized. A further large-scale prospective study will be needed in future. There is no consistent evidence about the management of ampullary tumors that exhibit positive or uncertain margins after being resected via EP. Our results might help to determine appropriate indications for EP, including for cases of early stage ampullary carcinoma.

In conclusion, resected margin positive or uncertain cases after EP could be managed by endoscopic treatment including APC, even in cases of adenocarcinoma. EP could become an effective less-invasive first-line treatment for early stage ampullary tumors.

The clinical outcomes of resected margin positive or uncertain cases after endoscopic papillectomy (EP) remains unknown.

The post-EP resection margins of ampullary tumors are often positive or uncertain because of the burning effect of EP. The clinical outcomes of resected margin positive or uncertain cases after EP remains unknown. Decisions regarding the treatment course in such cases might differ among institutions and/or depend on each patient’s condition.

To investigate the clinical outcomes of resected margin positive or uncertain cases after EP.

Forty-one patients with ampullary tumors who underwent EP at Kobe University Hospital between January 2007 and October 2018 were included in this study. The clinical outcomes of each EP cases were retrospectively investigated.

The resected margins were positive or uncertain in 24 patients (53.3%). Of these cases, 15 and 9 were diagnosed as adenoma and adenocarcinoma, respectively. Local tumor recurrence was detected in 3 cases. All of the recurrent tumors were successfully treated with argon plasma coagulation (APC). There was no local or lymph node recurrence after the APC. The post-APC follow-up periods lasted for 57.1 mo to 133.8 mo. No ampullary tumor-related deaths occurred in all patients.

In conclusion, resected margin positive or uncertain cases after EP could be managed by endoscopic treatment including APC, even in cases of adenocarcinoma.

Our results might help to determine appropriate indications for EP, including for cases of early stage ampullary carcinoma. A further large-scale prospective study will be needed in the future.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Haraldsson E, Luglio G, Ramia JM, Yang Z S- Editor: Ma RY L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Huang Y

| 1. | Li S, Wang Z, Cai F, Linghu E, Sun G, Wang X, Meng J, Du H, Yang Y, Li W. New experience of endoscopic papillectomy for ampullary neoplasms and other interventional techniques. Surg Endosc. 2018; Epub ahead of print. |

| 2. | De Palma GD, Luglio G, Maione F, Esposito D, Siciliano S, Gennarelli N, Cassese G, Persico M, Forestieri P. Endoscopic snare papillectomy: a single institutional experience of a standardized technique. A retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2015;13:180-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Sohn TA, Lillemoe KD, Pitt HA, Talamini MA, Hruban RH, Ord SE, Sauter PK, Coleman J, Zahurak ML, Grochow LB, Abrams RA. Six hundred fifty consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies in the 1990s: pathology, complications, and outcomes. Ann Surg. 1997;226:248-57; discussion 257-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1357] [Cited by in RCA: 1388] [Article Influence: 49.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (34)] |

| 4. | Böttger TC, Junginger T. Factors influencing morbidity and mortality after pancreaticoduodenectomy: critical analysis of 221 resections. World J Surg. 1999;23:164-171; discussion 171-172. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Ardengh JC. Kemp R, Lima-Filho ÉR, Dos Santos JS. Endoscopic papillectomy: The limits of the indication, technique and results. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;7:987-994. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ceppa EP, Burbridge RA, Rialon KL, Omotosho PA, Emick D, Jowell PS, Branch MS, Pappas TN. Endoscopic versus surgical ampullectomy: an algorithm to treat disease of the ampulla of Vater. Ann Surg. 2013;257:315-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Okano N, Igarashi Y, Hara S, Takuma K, Kamata I, Kishimoto Y, Mimura T, Ito K, Sumino Y. Endosonographic preoperative evaluation for tumors of the ampulla of vater using endoscopic ultrasonography and intraductal ultrasonography. Clin Endosc. 2014;47:174-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ridtitid W, Schmidt SE, Al-Haddad MA, LeBlanc J, DeWitt JM, McHenry L, Fogel EL, Watkins JL, Lehman GA, Sherman S, Coté GA. Performance characteristics of EUS for locoregional evaluation of ampullary lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:380-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ito K, Fujita N, Noda Y, Kobayashi G, Obana T, Horaguchi J, Koshita S, Kanno Y, Ogawa T, Kato Y, Yamashita Y. Impact of technical modification of endoscopic papillectomy for ampullary neoplasm on the occurrence of complications. Dig Endosc. 2012;24:30-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Alvarez-Sanchez MV, Oria I, Luna OB, Pialat J, Gincul R, Lefort C, Bourdariat R, Fumex F, Lepilliez V, Scoazec JY, Salgado-Barreira A, Lemaistre AI, Napoléon B. Can endoscopic papillectomy be curative for early ampullary adenocarcinoma of the ampulla of Vater? Surg Endosc. 2017;31:1564-1572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hornick JR, Johnston FM, Simon PO, Younkin M, Chamberlin M, Mitchem JB, Azar RR, Linehan DC, Strasberg SM, Edmundowicz SA, Hawkins WG. A single-institution review of 157 patients presenting with benign and malignant tumors of the ampulla of Vater: management and outcomes. Surgery. 2011;150:169-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Amini A, Miura JT, Jayakrishnan TT, Johnston FM, Tsai S, Christians KK, Gamblin TC, Turaga KK. Is local resection adequate for T1 stage ampullary cancer? HPB (Oxford). 2015;17:66-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | You D, Heo J, Choi S, Choi D, Jang KT. Pathologic T1 subclassification of ampullary carcinoma with perisphincteric or duodenal submucosal invasion: Is it T1b? Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138:1072-1076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kawabata Y, Ishikawa N, Moriyanma I, Tajima Y. What is an adequate surgical management for Tis and pT1 early ampullary carcinoma? Hepatogastroenterology. 2014;61:12-17. |

| 15. | Yamamoto K, Itoi T, Sofuni A, Tsuchiya T, Tanaka R, Tonozuka R, Honjo M, Mukai S, Fujita M, Asai Y, Matsunami Y, Kurosawa T, Yamaguchi H, Nagakawa Y. Expanding the indication of endoscopic papillectomy for T1a ampullary carcinoma. Dig Endosc. 2018; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Miyazaki M, Ohtsuka M, Miyakawa S, Nagino M, Yamamoto M, Kokudo N, Sano K, Endo I, Unno M, Chijiiwa K, Horiguchi A, Kinoshita H, Oka M, Kubota K, Sugiyama M, Uemoto S, Shimada M, Suzuki Y, Inui K, Tazuma S, Furuse J, Yanagisawa A, Nakanuma Y, Kijima H, Takada T. Classification of biliary tract cancers established by the Japanese Society of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery: 3(rd) English edition. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2015;22:181-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kang SH, Kim KH, Kim TN, Jung MK, Cho CM, Cho KB, Han JM, Kim HG, Kim HS. Therapeutic outcomes of endoscopic papillectomy for ampullary neoplasms: retrospective analysis of a multicenter study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017;17:69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Catalano MF, Linder JD, Chak A, Sivak MV, Raijman I, Geenen JE, Howell DA. Endoscopic management of adenoma of the major duodenal papilla. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:225-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 258] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Cheng CL, Sherman S, Fogel EL, McHenry L, Watkins JL, Fukushima T, Howard TJ, Lazzell-Pannell L, Lehman GA. Endoscopic snare papillectomy for tumors of the duodenal papillae. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:757-764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bohnacker S, Seitz U, Nguyen D, Thonke F, Seewald S, deWeerth A, Ponnudurai R, Omar S, Soehendra N. Endoscopic resection of benign tumors of the duodenal papilla without and with intraductal growth. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:551-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ridtitid W, Tan D, Schmidt SE, Fogel EL, McHenry L, Watkins JL, Lehman GA, Sherman S, Coté GA. Endoscopic papillectomy: risk factors for incomplete resection and recurrence during long-term follow-up. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:289-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Nam K, Song TJ, Kim RE, Cho DH, Cho MK, Oh D, Park DH, Lee SS, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH, Baek S. Usefulness of argon plasma coagulation ablation subsequent to endoscopic snare papillectomy for ampullary adenoma. Dig Endosc. 2018;30:485-492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Harewood GC, Pochron NL, Gostout CJ. Prospective, randomized, controlled trial of prophylactic pancreatic stent placement for endoscopic snare excision of the duodenal ampulla. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:367-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |