Published online Mar 7, 2018. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i9.1013

Peer-review started: November 25, 2017

First decision: December 27, 2017

Revised: January 15, 2018

Accepted: January 19, 2018

Article in press: January 19, 2018

Published online: March 7, 2018

Processing time: 100 Days and 21.3 Hours

To study implications of measuring quality indicators on training and trainees’ performance in pediatric colonoscopy in a low-volume training center.

We reviewed retrospectively the performance of pediatric colonoscopies in a training center in Malaysia over 5 years (January 2010-December 2015), benchmarked against five quality indicators: appropriateness of indications, bowel preparations, cecum and ileal examination rates, and complications. The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guideline for pediatric endoscopy and North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition training guidelines were used as benchmarks.

Median (± SD) age of 121 children [males = 74 (61.2%)] who had 177 colonoscopies was 7.0 (± 4.6) years. On average, 30 colonoscopies were performed each year (range: 19-58). Except for investigations of abdominal pain (21/177, 17%), indications for colonoscopies were appropriate in the remaining 83%. Bowel preparation was good in 87%. One patient (0.6%) with severe Crohn’s disease had bowel perforation. Cecum examination and ileal intubation rate was 95% and 68.1%. Ileal intubation rate was significantly higher in diagnosing or assessing inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) than non-IBD (72.9% vs 50.0% P = 0.016). Performance of four trainees was consistent throughout the study period. Average cecum and ileal examination rate among trainees were 97% and 77%.

Benchmarking against established guidelines helps units with a low-volume of colonoscopies to identify area for further improvement.

Core tip: Competency in colonoscopy is an essential component in the training for pediatric gastroenterology worldwide. We measured the performance of pediatric colonoscopy from a low-volume training center on quality indicators against established guidelines. The unit, which performed an average of 30 colonoscopies each year, performed well in clear indication for colonoscopy, good bowel preparation, safety and high rate of cecal examination (95%) but needs improvement for ileal intubation (at 68%). Benchmarking against established guidelines helps units with a low volume of colonoscopies to identify area for improvement.

- Citation: Lee WS, Tee CW, Koay ZL, Wong TS, Zahraq F, Foo HW, Ong SY, Wong SY, Ng RT. Quality indicators in pediatric colonoscopy in a low-volume center: Implications for training. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(9): 1013-1021

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v24/i9/1013.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i9.1013

Colonoscopy is an essential diagnostic procedure for the evaluation and treatment of lower gastrointestinal pathologies in children[1-4]. Major indications for colonoscopy in children include rectal bleeding, investigation of diarrhea, failure to thrive and perianal lesions, and as initial diagnostic evaluation for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)[5-10].

Approximately 20%-30% of IBD patients have onset of disease in childhood[11]. A study from Australia showed that IBD was the diagnosis in 58% of children who had initial diagnostic colonoscopy[5]. The percentage is much lower in Asia, ranging from 10.9% in Taiwanese children[8] to 19.6% in Korean children[7]. The incidence of IBD is increasing worldwide[12,13]. The incidence in Asia, including Malaysia, is increasing as well, although it is still relatively uncommon as compared to North America and Western Europe[13,14].

Competency in colonoscopy has become an essential component in the training syllabus for both adult and pediatric gastroenterology worldwide[15,16]. In adult colonoscopy, cecal intubation and detection for adenoma are considered as standard quality measures[15]. In children, however, routine screening for adenomas is generally not recommended[15]. On the other hand, ileal intubation is essential for accurate diagnosis of IBD, particularly Crohn’s disease (CD)[17]. Thus, appropriate indication for colonoscopy, complete examination including inspection of cecum and terminal ileum, adequate bowel preparation and free of complications are all important quality indicators in pediatric colonoscopy[16].

In areas where the prevalence of IBD is low, such as Malaysia, the volume of pediatric colonoscopies performed may be limited[7-10,18]. The reported cecum examination and ileal intubation rates vary. In Hong Kong, the cecal and ileal intubation rates were 97.6% and 75.6%[10]. In Taiwan, the ileal intubation rate was 77.5%[8]. In Australia, where the incidence of IBD is high, Singh et al[5] reported that the cecal and ileal intubation rates were 96.3% and 92.4%, respectively.

A study on quality indicators published previously showed that performance benchmarked against quality indicators varies in different centers[16]. To the best of our knowledge, however, no study on performance benchmarked against quality indicators from low-volume centers has been published previously.

We aimed to ascertain the performance of our unit when benchmarked against established quality indicators in pediatric colonoscopy covering the following areas: indications, quality of bowel preparation, safety and complications, cecal examination and terminal ileum intubation rates. We also assessed the implications of our performance to ascertain opportunities for improvements to the training program in this training center.

This was a retrospective review on all pediatric colonoscopies performed between January 2010 and December 2015 at the Paediatric Gastroenterology Unit, University Malaya Medical Centre (UMMC), Malaysia. The present study was approved by the institutional ethics review committee (MEC reference: 902.15). During the study period, the unit was staffed by one full-time consultant and a part-time visiting consultant. They were assisted by fellows-in-training, who spent the first 18 mo of a 3-year fellowship training program in the unit.

Cases were retrieved from hospital and the unit database. The following data were collected: demographics and clinical features; indications for colonoscopy; laboratory data; degree of bowel preparation; extent of colonoscopic examination; and complications. Colonoscopic and pathological diagnoses were ascertained. Cases were excluded if the data were incomplete.

The following areas were used as quality indicators: (1) appropriateness of indications; (2) quality of bowel preparation and extent of colonoscopic examination, including (3) cecum examination and (4) ileal intubation; and (5) safety (including anesthesia and sedation) and complications. Factors affecting extent of examination and the performances of trainees were also analyzed.

In our unit, each referral for colonoscopy was screened and decided by a consultant. Generally, the indications for colonoscopy followed the established guidelines[3,4], and has been reported previously[18]. For the purpose of the present study, the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline for pediatric endoscopy was used as a benchmark[4].

In our unit, colonoscopies were usually performed under general anesthesia. In adolescents, sedation (generally a combination of midazolam and pethidine) was used occasionally at the discretion of the anesthetist.

Bowel preparation has been standardized throughout the study period. Two days prior to colonoscopy, each patient was allowed a low residue diet. On the night before the procedure, each patient had bowel cleansing with polyethylene glycol solution and glycerin rectal enema. The degree of bowel preparation observed during colonoscopy was not standardized. It was judged by the endoscopist as poor, fair, good or excellent[6].

The extent of the colonoscopy was confirmed by visual identification of the colonic wall appearance, and the anatomy the cecum and terminal ileum. The biopsy of the terminal ileum was also used as an additional confirmation. The recommendation by North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) guidelines for training in pediatric gastroenterology was used as a benchmark[19]. The NASPGHAN guidelines recommends a cecum and ileal examination rate of between 90%-95%[19].

For the purpose of the present study, analysis on performance was confined to colonoscopies where an inspection of ileum was intended. This included cases where intubation of terminal ileum was indicated (i.e., in diagnosing or assessing IBD), feasible (acceptable quality of bowel preparation where full examination was feasible) or safe (benefit of ileal intubation outweighs the risk of full examination, such as bowel perforation).

Analysis on the performance by trainees was confined to trainees who had completed a minimum of 12 mo training in the unit during the study period. Number of colonoscopies performed, cecum examination and ileal intubation rates were noted. In colonoscopies where trainees encountered technical difficulties during the procedure and were subsequently taken over by the consultant, the procedures were logged as performed by the consultant.

Data were collected and managed by using a statistical software program (SPSS version 20.0; SPSS Inc., IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Descriptive data were described in percentage, mean and median. Categorical data were analyzed using a two-tailed χ2 test.

During the 6-year study period, 194 colonoscopies were performed in the unit. Data on 17 procedures were incomplete and were excluded from analysis. Of the remaining 177 colonoscopies, 56 were repeated procedures. Thus, 121 patients who had 177 colonoscopies were analyzed. The results are presented in two parts: (1) indications, colonoscopic findings and diagnosis of 121 patients who had first colonoscopy; and (2) quality indicators of 177 colonoscopies performed.

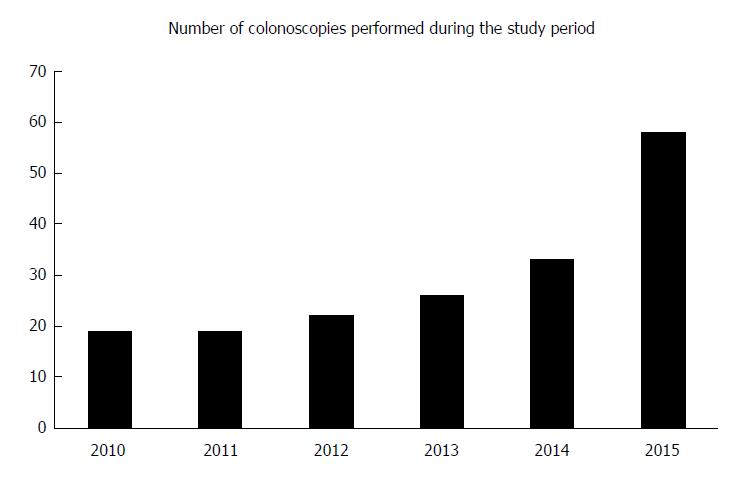

There was a steady increase in the number of colonoscopies performed each year during the study period (Figure 1). On average, 30 colonoscopies were performed each year during the study period, ranging from 19 procedures per year in the first 2 years to 58 procedures in 2015. Among the procedures, 15% (27/177) were logged as performed by consultants, while the remaining 85% (150/177) were performed by trainees supervised by a consultant.

There was a male preponderance (males = 74, 61%) in the 121 patients who had first colonoscopy (Table 1). The median (± SD) age was 7.5 (± 4.5) years. Eighty-one (67%) patients also had concomitant esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy (EGDS).

| n | % | |

| Sex, males | 74 | 61 |

| Age in yr, median ± SD | 7.5 ± 4.5 | |

| Concomitant esophagogastroduodenoscopy | 81 | 67 |

| Indications, n = 1211 | ||

| Suspected of inflammatory bowel disease, new patients | 36 | 30 |

| Per rectal bleeding/investigations of anemia | 25 | 21 |

| Investigation of gastrointestinal symptoms | 21 | 17 |

| Assessment of inflammatory bowel disease, diagnosed elsewhere | 16 | 13 |

| Suspected of colonic polyps | 7 | 6 |

| Exclusion of graft-versus-host disease or colonic malignancies | 7 | 6 |

| Assessment of failure to thrive/malabsorption | 4 | 3.3 |

| Others | 10 | 8 |

| Colonoscopic diagnosis, n = 121 | ||

| Crohn’s disease | 30 | 25 |

| Ulcerative colitis | 20 | 17 |

| Non-specific colitis or solitary rectal ulcer syndrome | 22 | 18 |

| Infective colitis | 9 | 7 |

| Colonic polyps | 8 | 7 |

| Graft-versus-host disease | 5 | 4 |

| Malabsorption | 2 | 2 |

| Allergic colitis | 2 | 2 |

| Miscellaneous diagnosis | 5 | 4 |

| No diagnosis | 18 | 15 |

| Extent of colonoscopic examination, 177 colonoscopies | ||

| Terminal ileum | 96 | 54 |

| Cecum | 38 | 21 |

| Ascending colon | 9 | 5 |

| Transverse colon | 13 | 7 |

| Descending colon | 12 | 7 |

| Sigmoid colon | 7 | 4 |

| Rectum | 1 | 0.6 |

| Reached cecum but no terminal ileum intubation | 134 | 76 |

| Ileal intubation not intended, 177 colonoscopies2 | 36 | |

| Not indicated | 18 | |

| Distorted anatomy due to previous surgery | 1 | |

| External stricture | 2 | |

| Previous colostomy in Crohn’s disease | 4 | |

| Large polyp at rectum | 2 | |

| Risk of perforation outweighs benefit of full examination due to | 5 | |

| Severe colitis | ||

| Poor bowel preparation | 4 | |

| Full colonoscopic examination intended, 177 colonoscopies2 | 141 | |

| Ileal intubation | 96 | 68 |

| Cecum examination | 134 | 95 |

The most common indication was confirming the diagnosis of IBD (36/121, 30%; Table 1). Others were investigation of anemia or rectal bleeding (25/121, 21%). Investigation of abdominal pain was the indication in 17% (21/121). Most of the repeat colonoscopies were for disease assessment in IBD.

A positive finding was noted in 68 (56.2%) colonoscopies, while the remaining 53 (43.8%) had a normal colonoscopic finding. Indications for colonoscopy for the 53 patients with a negative finding were: excluding IBD (n = 18); disease assessment of pre-existing IBD (n = 4); assessment of abdominal pain (n = 8); ascertainment of lower gastrointestinal bleeding (n = 10); and, miscellaneous (n = 13).

In addition to 16 patients who had colonoscopic assessment of preexisting IBD, a new clinical diagnosis or institution of new therapeutic measures was made in another 87 patients following colonoscopy. Thus, a total of 103 patients had a positive diagnosis. The diagnostic yield was 85%.

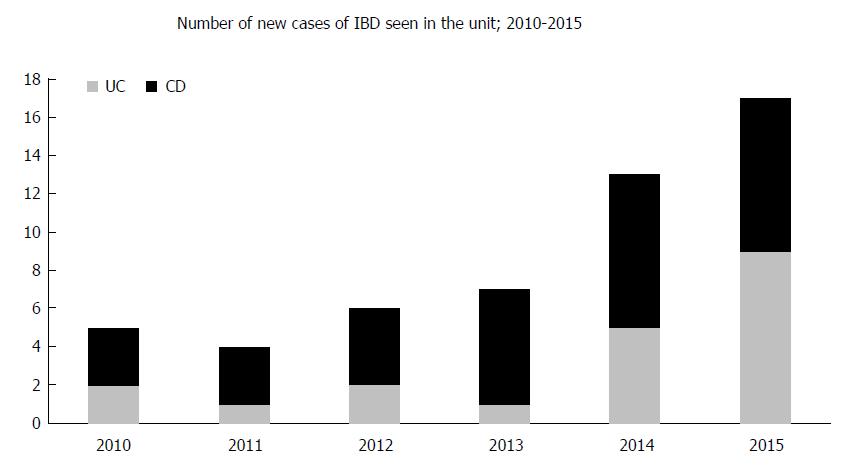

The colonoscopic diagnoses are shown in Table 1. Overall, 50 (41%) patients had a diagnosis of IBD (newly diagnosed, n = 34; diagnosis confirmed elsewhere, n = 16; Figure 2). Of these, 30 patients had CD and 20 had ulcerative colitis, respectively. Another 22 (18%) patients had focal inflammation of the rectum (IBD-unclassified) or solitary rectal ulcer syndrome.

The number of new cases of IBD seen in the unit during the study period is shown in Figure 2. There was an increasing trend in the number of new IBD cases, especially for CD.

Vast majority (165/177, 93.2%) of the procedures were performed under general anesthesia. The remaining 12 procedures (6.8%) were performed under sedation, being administered by anesthetist. No major events related to anesthesia or sedation were observed during the study period.

Bowel preparation was judged to be good by the endoscopist in 87% (155/177) of the patients, moderate in 0.6% (1/177) and bad in 12% (21/177) patients.

Information on the extent of colonoscopy was available in all 177 procedures (Table 1). The overall ileal intubation rate was 54.2% (96/177). Cecum was examined in an additional 22.0% (39/177). Thus, the cecum was reached in 76.3% (135/177) of patients. The extents of colonoscopy of the remaining 42 procedures are shown in Table 1.

In 36 patients, full colonoscopic examination and ileal intubation were not intended. They were not indicated in 18 cases, including those for confirmation or surveillance of graft-versus-host disease (n = 10), confirmation of rectal metastasis (n = 2), tissue biopsy for malabsorption (1 each for food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome and autoimmune enteropathy), trichuriasis (n = 2), and assessment of previously confirmed solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (n = 2). Risk of perforation was judged to outweigh benefit of full examination in 5 patients. All had IBD with severe colitis and friable mucosal wall (ulcerative colitis, n = 3; CD, n = 2). Poor bowel preparation prevented a complete examination in 4 patients. A large rectal polyp obstructing the lumen (n = 1) and excessive bleeding in a patient with a large rectal polyp (n = 1) prevented a complete colonoscopy in 2 patients.

Of the remaining 141 patients in whom inspection of the terminal ileum was intended, the cecum examination and ileal intubation rates were 95.0% (134/141) and 68.1% (96/141), respectively. Overall, 45.8% of colonoscopies did not include an inspection of terminal ileum, and 31.9% did not reach terminal ileum when it was intended. Similarly, 24.3% of the procedures did not reach the cecum, and 5.0% failed to reach cecum when it was intended.

Rate of complete examination was not significantly affected by the age of patients [ileal intubation rate; < 5 years (35/141) vs ≥ 5 years (106/141) = 62.9% vs 69.8% P = 0.44]. However, the ileal intubation rate was significantly higher when the indication for the colonoscopy was for the diagnosis or assessment of IBD (73.0% vs 50%; P = 0.016).

During the study period, four trainees completed a minimum of 12-mo training in pediatric colonoscopy in the unit (Table 2). Part of the training period of another three trainees fell outside the study period and were not included in the analysis. The average number of colonoscopies performed was 29. The overall cecum examination rate was 97%, while the overall ileal intubation rate was 77%. There was a consistent performance by the trainees (Table 2).

| Trainee A | Trainee B | Trainee C | Trainee D | Average | |

| Duration of training in mo | 18 | 18 | 24 | 18 | 19.5 |

| Number of colonoscopies performed during training period | 19 | 17 | 44 | 36 | 29 |

| Number of colonoscopies where intubation of terminal ileum was intended | 16 | 13 | 39 | 28 | 24 |

| Intubation of terminal ileum | 12 (75) | 10 (77) | 34 (87) | 18 (64) | 77% |

| Examination of cecum and terminal ileum | 16 (100) | 13 (100) | 38 (97) | 26 (93) | 97% |

A 7-year-old boy with CD who had gross delay in referral, severe malnutrition and severe mucosal ulcerations had iatrogenic perforation of the colon during the procedure. The patient had an uneventful recovery after colostomy and repair. Another patient with rectal polyp developed bleeding while it was removed during colonoscopy. The bleeding stopped after cauterization. No blood transfusion was required. No other complications were noted in the remaining 175 procedures, either associated with the procedure, anesthesia or sedation.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first of its kind on performance benchmarked against established quality indicators in pediatric colonoscopy from a center where the volume of colonoscopy is low. During the study period, the number of colonoscopies performed in the center each year ranged from 19 to 58, with an average of 30. It was conducted in a setting with a low but rapidly increasing incidence of IBD.

Our results reveal that of the five quality indicators which were benchmarked against, the performance was high in four indicators. Most of the indications for colonoscopy performed in the unit were appropriate, following the recommendations of ESGE guidelines. Performances were good in bowel preparation, patient safety and complications. The cecum examination rate reached the expected rate at 95% by NASPGHAN, but was somewhat limited in ileal intubation rate at 68.1%. The performance of all trainees was consistently good in cecum examination but variable in ileal intubation.

There are several important implications on the results of the present study. Firstly, the indications for colonoscopies in the present study were mostly appropriate according to established guidelines[4]. The overall diagnostic yield was 85%. Previously, we observed that 99.7% of all EGDS and colonoscopies performed in the unit were appropriate[18]. The most common indications for colonoscopy were diagnosing or assessing IBD and ascertaining the cause of anemia. There was an increasing trend in the number of newly-diagnosed IBD cases during the study period. Investigation of abdominal symptoms, mainly abdominal pain, was the indication in only 17% of the patients[4].

In adult colonoscopy, screening for colon cancer is the main quality indicator[19]. Surrogate measures, such as colonic adenoma detection and complete examination of the colon, have been found to correlate with high-quality colonoscopy[20]. Pediatric colonoscopy, on the other hand, is fundamentally a different procedure with different indications, technical requirement, and different quality indicators[21]. The most important difference between adult and pediatric colonoscopies are the size of the patients and indications[21].

Screening for IBD is an important indication in pediatric colonoscopy. Differentiating between ulcerative colitis and CD is important in the diagnosis of IBD. Thus, examination of the cecum and terminal ileum are important quality indicators in pediatric colonoscopy[22]. In particular, intubation of the terminal ileum and sampling biopsy is essential for confirming the diagnosis of CD[23,24]. Pediatric endoscopy training guidelines suggest the cecal intubation rate to be at least 90% to 95%, with a comparable terminal ileum intubation rate[16,19].

Based on these quality indicators, the performances of centers vary. In Australia where screening for IBD was the major indication for colonoscopy, the reported cecum and ileal examination rates were 96.3% and 92.4%, respectively[5]. In Taiwan, the reported ileal intubation rate was 77.5%, while in China it was 81.7%[8,9]. The ileal intubation rates in the multicenter consortium review from the United States ranged from 30% to 90%[16].

After excluding procedures where either complete colonoscopy was not indicated, unsafe or not feasible, the cecum examination and ileal intubation rates in the present study were 95% and 68.1%, respectively. The cecum examination was comparable to the NASPGHAN pediatric gastroenterology training guidelines[19], but the ileal intubation rate was somewhat lower. Nevertheless, these figures were comparable with those reported in the region and the United States multicenter consortium study[8,16].

Bowel preparation was noted to be good in the majority of the cases (87%). Colonic perforation was observed in 1 patient who had severe long-standing CD prior to referral. The perforation rate was 0.5%. We reported two perforations in 66 colonoscopies previously[18].

The present study showed that all the trainees have a satisfactory cecum intubation rate, although the ileal intubation rate needs to be improved. To achieve cecal intubation examination and ileal intubation rate of 90%-95%, NASPGHAN guidelines for training in pediatric gastroenterology recommended 120 colonoscopies for pediatric trainees[19]. In this center, each trainee performed about 12-20 colonoscopies in children each year during their training. Before starting pediatric colonoscopy under supervision, the trainees were required to undergo training in adult colonoscopy, performing at least 50 colonoscopies in adult patients.

The implication of this is that the trainees would not have adequate training opportunity of reaching the recommended 120 colonoscopies in pediatric colonoscopy if the entire training was spent in this unit alone. Trainees spent between 18 mo to 24 mo of training in this center. The trainees usually start the training in endoscopic procedures with the adult gastroenterologists before being allowed to perform pediatric colonoscopy. The final year of the training is usually spent in a center of excellence for training in Australia or United Kingdom, where there is abundant opportunity for pediatric colonoscopy. Thus, even though the ileal intubation rate of the trainees noted in the present study did not reach the intended goal suggested by the NASPGHAN training guidelines[19], it is expected that their performance will be enhanced further once the oversea training is completed.

Another potential way to enhance colonoscopic skills is simulated colonoscopy training[25]. Studies involving trainees in adult colonoscopy showed improved performances during patient-based colonoscopy[25]. However, to date, no such study has been published involving training in pediatric colonoscopy.

Other important quality indicators which were not included in the present study were documentation of American Society of Anesthesiologist Physical Status Classification System (ASA) risk assessment and procedure duration. ASA risk assessment was routinely checked by the anesthetist. It was documented separately but was not captured in the present study. Additional potential measures of high-quality pediatric colonoscopy which have been mentioned but not included in this study are minimization of air insufflation, ease of patient sedation, duration of procedure, performance of mucosal biopsy sampling, patient recovery time and ongoing procedural competency assessment[22].

An obvious limitation to this study is its retrospective nature. The data was only collected from one center. However, our center is the only training center for pediatric gastroenterology in the whole country; we are unable to benchmark our performance against other centers. Nevertheless, with the exception of a somewhat lower ileal intubation rate, the performance in other quality indicators is excellent.

In conclusion, there is an increasing trend in the number of colonoscopies performed each year in this center. This is due to the increasing number of newly-diagnosed IBD cases during the study period. The performance of pediatric colonoscopy in this center was excellent in four of the five quality indicators benchmarked. The ileal intubation rate needs to be improved. A period of training in a center with a large volume of IBD will enhance the skills and performance of colonoscopy among the trainees of pediatric gastroenterology in Malaysia.

The incidence of inflammatory bowel disease is on the rise worldwide, including in Asia. The gold standard for the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease is histologic confirmation from tissue biopsies obtained during esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy and colonoscopy. In particular, differentiating Crohn’s disease from ulcerative colitis is dependent upon inspection and biopsy of the terminal ileum. Thus, intubation of the terminal ileum is considered as an important quality indicator in pediatric colonoscopy. Current guidelines by the North American Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition recommend the cecum examination and terminal ileum of 95%. This target should be used by pediatric gastroenterology centers worldwide to benchmark their performance.

Current literature showed that reported ileal intubation rate in pediatric colonoscopy from centers around Asia ranged from 75.6% to 77.5%. The performance of our unit, from an area where the incidence of inflammatory bowel disease is currently low but is on the rise, is unknown. Thus, we were motivated to benchmark our performance against current recommendation to identify areas for improvement to enhance the quality of our training program.

The main objective was to benchmark the performance of our unit, in particular the completeness of colonoscopic examination, i.e. cecal examination and ileal intubation, against current recommended guidelines. We also evaluated other indicators such as appropriateness of indications, level of bowel preparation, as well as safety and complications of the procedures encountered.

We conducted a retrospective analysis on all the pediatric colonoscopies performed in a pediatric gastroenterology training center in Malaysia over a period of 6 years. We included the following indicators: appropriateness of indications; quality of bowel preparation; safety and complications; as well as cecal examination and terminal ileum intubation rates. The performances of trainees in the cecal and ileal examination rates were ascertained separately.

We found that of the 177 colonoscopies performed, the diagnostic yield was 85%, quality of bowel preparation was good in 87%, while one of 177 procedures was complicated by perforation during the procedure. The overall cecum examination rate was 76.3% and ileal intubation rate was 54.2%. After excluding colonoscopy where full colonoscopic examination was either not indicated, not feasible because of poor bowel preparation or unsafe (severe colitis), the cecum examination rate was 95.0% and ileal intubation rate was 68.1%. Among four trainees who completed a minimum of 12 mo training, the overall cecum rate was 97% while the overall ileal intubation rate was 77%. The performance of all trainees was consistent. Thus, the cecum examination rate of our unit was satisfactory but the rate of terminal ileum intubation needs further improvement. To improve the rate of ileal intubation, the trainees would spend part of their training program in a center of excellence with adequate volume of pediatric colonoscopy.

The present study was the first attempt by a pediatric gastroenterology unit in Asia to benchmark its performance in pediatric colonoscopy against established international guidelines. Our study suggests that such a benchmark is both applicable and desirable. The study allows our unit to identify areas for further improvement. Trainees from our unit now routinely spend part of their training in a center of excellence to enhance their skills in colonoscopy.

Benchmarking against established guidelines has been adopted as part of quality assurance of our unit. We plan to conduct a prospective study to include other indicators of good practice not included in this retrospective review. These include anesthetic risk assessment, duration of procedure, ease of sedation, quality of mucosal biopsy sampling and patient recovery time.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Malaysia

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Choi YS S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Huang Y

| 1. | Teague RH, Salmon PR, Read AE. Fibreoptic examination of the colon: a review of 255 cases. Gut. 1973;14:139-142. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Hassall E, Barclay GN, Ament ME. Colonoscopy in childhood. Pediatrics. 1984;73:594-599. [PubMed] |

| 3. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Lightdale JR, Acosta R, Shergill AK, Chandrasekhara V, Chathadi K, Early D, Evans JA, Fanelli RD, Fisher DA, Fonkalsrud L, Hwang JH, Kashab M, Muthusamy VR, Pasha S, Saltzman JR, Cash BD; American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Modifications in endoscopic practice for pediatric patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:699-710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Thomson M, Tringali A, Dumonceau JM, Tavares M, Tabbers MM, Furlano R, Spaander M, Hassan C, Tzvinikos C, Ijsselstijn H. Paediatric Gastrointestinal Endoscopy: European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition and European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Guidelines. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;64:133-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Singh HK, Withers GD, Ee LC. Quality indicators in pediatric colonoscopy: an Australian tertiary center experience. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52:1453-1456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wahid AM, Devarajan K, Ross A, Zilbauer M, Heuschkel R. Paediatric gastrointestinal endoscopy: a qualitative study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28:25-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lee YW, Chung WC, Sung HJ, Kang YG, Hong SL, Cho KW, Kang D, Lee IH, Jeon EJ. Current status and clinical impact of pediatric endoscopy in Korea. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2014;64:333-339. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Wu CT, Chen CA, Yang YJ. Characteristics and Diagnostic Yield of Pediatric Colonoscopy in Taiwan. Pediatr Neonatol. 2015;56:334-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lei P, Gu F, Hong L, Sun Y, Li M, Wang H, Zhong B, Chen M, Cui Y, Zhang S. Pediatric colonoscopy in South China: a 12-year experience in a tertiary center. PLoS One. 2014;9:e95933. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tam YH, Lee KH, Chan KW, Sihoe JD, Cheung ST, Mou JW. Colonoscopy in Hong Kong Chinese children. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1119-1122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ruel J, Ruane D, Mehandru S, Gower-Rousseau C, Colombel JF. IBD across the age spectrum: is it the same disease? Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11:88-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ng SC, Tang W, Ching JY, Wong M, Chow CM, Hui AJ, Wong TC, Leung VK, Tsang SW, Yu HH, Li MF, Ng KK, Kamm MA, Studd C, Bell S, Leong R, de Silva HJ, Kasturiratne A, Mufeena MN, Ling KL, Ooi CJ, Tan PS, Ong D, Goh KL, Hilmi I, Pisespongsa P, Manatsathit S, Rerknimitr R, Aniwan S, Wang YF, Ouyang Q, Zeng Z, Zhu Z, Chen MH, Hu PJ, Wu K, Wang X, Simadibrata M, Abdullah M, Wu JC, Sung JJ, Chan FK; Asia–Pacific Crohn’s and Colitis Epidemiologic Study (ACCESS) Study Group. Incidence and phenotype of inflammatory bowel disease based on results from the Asia-pacific Crohn’s and colitis epidemiology study. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:158-165.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 515] [Cited by in RCA: 589] [Article Influence: 49.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Malmborg P, Hildebrand H. The emerging global epidemic of paediatric inflammatory bowel disease--causes and consequences. J Intern Med. 2016;279:241-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hilmi I, Jaya F, Chua A, Heng WC, Singh H, Goh KL. A first study on the incidence and prevalence of IBD in Malaysia--results from the Kinta Valley IBD Epidemiology Study. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:404-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Walsh CM, Ling SC, Mamula P, Lightdale JR, Walters TD, Yu JJ, Carnahan H. The gastrointestinal endoscopy competency assessment tool for pediatric colonoscopy. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;60:474-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Thakkar K, Holub JL, Gilger MA, Shub MD, McOmber M, Tsou M, Fishman DS. Quality indicators for pediatric colonoscopy: results from a multicenter consortium. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:533-541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Levine A, Koletzko S, Turner D, Escher JC, Cucchiara S, de Ridder L, Kolho KL, Veres G, Russell RK, Paerregaard A. ESPGHAN revised porto criteria for the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;58:795-806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 822] [Cited by in RCA: 974] [Article Influence: 88.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lee WS, Zainuddin H, Boey CC, Chai PF. Appropriateness, endoscopic findings and contributive yield of pediatric gastrointestinal endoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:9077-9083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Leichtner AM, Gillis LA, Gupta S, Heubi J, Kay M, Narkewicz MR, Rider EA, Rufo PA, Sferra TJ, Teitelbaum J; NASPGHAN Training Committee; North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology. NASPGHAN guidelines for training in pediatric gastroenterology. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;56 Suppl 1:S1-S8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Rex DK. Quality in colonoscopy: cecal intubation first, then what? Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:732-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Rex DK. Colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:444-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kay M, Wyllie R. It’s all about the loop: quality indicators in pediatric colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:542-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Sawczenko A, Sandhu BK. Presenting features of inflammatory bowel disease in Great Britain and Ireland. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:995-1000. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Batres LA, Maller ES, Ruchelli E, Mahboubi S, Baldassano RN. Terminal ileum intubation in pediatric colonoscopy and diagnostic value of conventional small bowel contrast radiography in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;35:320-323. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Grover SC, Scaffidi MA, Khan R, Garg A, Al-Mazroui A, Alomani T, Yu JJ, Plener IS, Al-Awamy M, Yong EL. Progressive learning in endoscopy simulation training improves clinical performance: a blinded randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;86:881-889. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |