Published online Feb 14, 2018. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i6.737

Peer-review started: November 8, 2017

First decision: November 21, 2017

Revised: December 5, 2017

Accepted: January 1, 2018

Article in press: January 1, 2018

Published online: February 14, 2018

Processing time: 90 Days and 13.6 Hours

To investigate the performance of transient elastography (TE) for diagnosis of fibrosis in patients with autoimmune hepatitis-primary biliary cholangitis (AIH-PBC) overlap syndrome.

A total of 70 patients with biopsy-proven AIH-PBC overlap syndrome were included. Spearman correlation test was used to analyze the correlation of liver stiffness measurement (LSM) and fibrosis stage. Independent samples Student’s t-test or one-way analysis of variance was used to compare quantitative variables. Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve was used to calculate the optimal cut-off values of LSM for predicting individual fibrosis stages. A comparison on the diagnostic accuracy for severe fibrosis was made between LSM and other serological scores.

Patients with AIH-PBC overlap syndrome had higher median LSM than healthy controls (11.3 ± 6.4 kPa vs 4.3 ± 1.4 kPa, P < 0.01). LSM was significantly correlated with fibrosis stage (r = 0.756, P < 0.01). LSM values increased gradually with an increased fibrosis stage. The areas under the ROC curves of LSM for stages F ≥ 2, F ≥ 3, and F4 were 0.837 (95%CI: 0.729-0.914), 0.910 (0.817-0.965), and 0.966 (0.893-0.995), respectively. The optimal cut-off values of LSM for fibrosis stages F ≥ 2, F ≥ 3, and F4 were 6.55, 10.50, and 14.45 kPa, respectively. LSM was significantly superior to fibrosis-4, glutaglumyl-transferase/platelet ratio, and aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index scores in detecting severe fibrosis (F ≥ 3) (0.910 vs 0.715, P < 0.01; 0.910 vs 0.649, P < 0.01; 0.910 vs 0.616, P < 0.01, respectively).

TE can accurately detect hepatic fibrosis as a non-invasive method in patients with AIH-PBC overlap syndrome.

Core tip: Our research determined that transient elastography can accurately detect hepatic fibrosis as a non-invasive method in patients with autoimmune hepatitis-primary biliary cholangitis overlap syndrome. Liver stiffness measurements were significantly superior to fibrosis-4, glutaglumyl-transferase/platelet ratio, and aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index scores for detecting severe fibrosis.

- Citation: Wu HM, Sheng L, Wang Q, Bao H, Miao Q, Xiao X, Guo CJ, Li H, Ma X, Qiu DK, Hua J. Performance of transient elastography in assessing liver fibrosis in patients with autoimmune hepatitis-primary biliary cholangitis overlap syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(6): 737-743

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v24/i6/737.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i6.737

Liver fibrosis, characterized by the accumulation of the extracellular matrix, has been considered a common progressive stage and predictor of undesirable prognosis in various chronic liver diseases[1]. The evaluation of fibrosis is crucial in the assessment of chronic liver diseases. Liver biopsy remains the gold standard for evaluating fibrosis but has some drawbacks, which has led to the development of non-invasive methods.

Transient elastography (TE) by FibroScan based on ultrasound can noninvasively evaluate liver fibrosis via liver stiffness measurement (LSM)[2]. It has been introduced as a non-invasive surrogate to liver biopsy for detection of hepatic fibrosis in patients with various chronic liver diseases[3-6]. Numerous studies have shown that LSM values have a good correlation with histological fibrosis stages. Furthermore, compared to other serum biomarkers, such as aspartate aminotransferase (AST)-to-platelet ratio index (APRI), and fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) scores, LSM is probably the most validated non-invasive method to assess the stage of fibrosis with better diagnostic accuracy[3,7,8].

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) and primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) are two immune-mediated chronic liver diseases targeting hepatocytes and biliary epithelial cells, respectively[9]. The overlap syndrome of AIH-PBC shares clinical, biochemical, serological, and histological features of patients with AIH and PBC[10]. AIH is usually a chronic and long-term disease, and approximately 25% of patients with AIH progress to hepatic fibrosis or cirrhosis despite immunosuppression intervention[11]. Recently, studies reported that patients with AIH-PBC overlap syndrome exhibited a lower response rate to ursodeoxycholic acid and steroid combination therapy while having a more severe clinical prognosis compared with AIH patients[12]. Therefore, accurately assessing hepatic fibrosis and initiating anti-fibrotic intervention are essential for some AIH-PBC overlap syndrome patients with rapid disease progression. Our recent study revealed that TE can reliably stage liver fibrosis in AIH patients[13]. However, the evaluation of TE in assessing liver fibrosis in patients with AIH-PBC overlap syndrome remains limited.

In the current study, we assessed the diagnostic performance of TE in evaluating liver fibrosis in biopsy-proven AIH-PBC overlap syndrome patients and made a comparison with other non-invasive methods.

Patients who were suspected to have AIH-PBC overlap syndrome and eventually underwent liver biopsy at Renji Hospital (Shanghai, China) from September 2014 to July 2017 were recruited in this retrospective study. Ultimately, a total of 70 patients met the Paris AIH-PBC overlap syndrome criteria[10]. Briefly, the requirement of at least two out of three specific criteria in each condition was met. The PBC criteria included: (1) alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels at least twice the upper limit of normal (ULN) or gamma glutamyltransferase (GGT) levels at least five times the ULN; (2) anti-mitochondrial antibody (AMA) positivity; and (3) florid bile duct lesion in liver biopsy. The AIH criteria comprised of: (1) alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels at least five times the ULN; (2) IgG levels at least twice the ULN or anti-smooth muscle antibody (ASMA) positivity; and (3) moderate to severe periportal or periseptal lymphocytic piecemeal necrosis in histological examination. All patients received no immunosuppressive therapy before liver biopsy.

The exclusion criteria included chronic infection with hepatic virus B or C, primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), PBC, AIH, drug-induced liver disease, alcoholic or non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, hereditary metabolic liver disease, hepatobiliary parasitic infection, and severe systemic disease. Patients with acute severe attack with markedly elevated serum aminotransferase levels (ALT > 1000 U/L) and severe jaundice were excluded. Decompensated cirrhosis with ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, gastrointestinal bleeding, and hepatic carcinoma were excluded. Each participant of this study provided written informed consent.

Percutaneous liver biopsy guided by ultrasound was performed in all patients under local anesthesia using a 16G disposable needle. Liver specimens at least 1 cm in length with eight complete portal tracts were included. The specimens were fixed in 10% neutral formalin immediately and embedded in paraffin. Hematoxylin and eosin staining was used to observe the morphology of the liver, and Masson’s trichrome and reticulin staining was performed to detect fibrosis. Liver fibrosis and necroinflammatory activity were evaluated by a single experienced pathologist who was blinded to the patients’ clinical data. A METAVIR-derived scoring system was used for evaluating liver fibrosis and inflammation by a single senior pathologist[14]. In brief, the fibrosis stage description was F0, no fibrosis; F1, portal fibrosis without septa; F2, portal and periportal fibrosis with few septa; F3, portal and periportal fibrosis with numerous septa without cirrhosis; and F4, cirrhosis. Hepatic inflammatory activity was graded as follows: A0, none; A1, mild; A2, moderate; and A3, severe.

Medical records of all patients diagnosed with AIH-PBC overlap syndrome were reviewed, and clinical data and laboratory findings were collected and analyzed. Laboratory evaluations included liver biochemistry [i.e., ALT, AST, ALP, GGT, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, globulin, and albumin], serum immunoglobulins (IgG, IgM, and IgA), routine blood test (white blood cell count and platelet count), and prothrombin time. APRI score was calculated by using the formula of Wai et al[15] [(AST/ULN considered as 40 IU/L)/platelet count × 109/L]. FIB-4 score was calculated by using the formula of Sterling et al[16] [(age × AST)/(platelet count × ALT1/2)]. GGT/platelet ratio (GPR) was calculated by using the formula of Lemoine et al (GGT/platelet count × 109/L)[17]. The serum autoantibodies, including anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), AMA, and ASMA were detected by indirect immunofluorescence (Euroimmun AG, Hangzhou, China).

TE measured with a FibroScan device and an M probe ultrasound transducer (both from Echosens, Paris, France) was performed in all patients who underwent liver biopsy on the same day. According to the ultrasonography images, we selected an appropriate area for detection that contained at least 6-cm-thick liver parenchyma with absence of main blood vessels and the gallbladder. We obtained 10 valid LSMs from each participant and considered LSM with an interquartile range ≤ 30% and a success rate ≥ 60% as reliable. The median value represented the value of LSM expressed in kilopascals (kPa). All the measurements were performed following the manufacturer’s instructions. LSM assessment of 25 healthy people as normal controls was also performed.

Data were analyzed using SPSS software version 22.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, United States). Normally distributed continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± SD. Quantitative variables were compared using independent samples Student’s t-test or one-way analysis of variance when appropriate. The Spearman’s rank correlation test was used to explore the correlation between the LSM and fibrosis grade. The diagnostic accuracy of LSM for the prediction of fibrosis stages was calculated using a receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve. Optimal LSM cut-off values for F2-4 fibrosis were determined based on the highest combined sensitivity and specificity (Youden index). The performance characteristics of each cut-off value in terms of sensitivity and specificity were calculated. The areas under the ROC curves (AUROCs) were calculated to compare the diagnostic efficiency of each noninvasive predictor for severe fibrosis. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 70 biopsy-proven AIH-PBC overlap syndrome patients were included, with a mean age of 46.6 ± 10.2, and 84.3% of patients were female. In all patients, the prevalence of autoantibodies, including ANA, AMA, and ASMA, was 94.3%. AIH-PBC overlap syndrome was diagnosed based on the Paris criteria. The general characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1.

| Characteristic | n = 70 |

| Age | 46.6 ± 10.2 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 11 (15.7) |

| Female | 59 (84.3) |

| Autoantibody positive rate | 94.3 |

| Liver function test (mean ± SD) | |

| ALT (U/L) | 185.6 ± 238.9 |

| AST (U/L) | 166.6 ± 190.7 |

| GGT (U/L) | 363.2 ± 393.3 |

| ALP (U/L) | 318.7 ± 245.9 |

| Total bilirubin (μmol/L) | 32.3 ± 33.9 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 40.1 ± 8.0 |

| Serum IgG level (g/L) | 17.0 ± 5.1 |

| Serum IgM level (g/L) | 4.2 ± 6.9 |

| Biochemical score (mean ± SD) | |

| APRI | 2.47 ± 3.85 |

| FIB-4 | 3.22 ± 3.53 |

| GPR | 1.93 ± 2.28 |

| Liver biopsy | |

| Fibrosis stage | |

| 0 | 0 (0) |

| 1 | 9 (12.9) |

| 2 | 29 (41.4) |

| 3 | 25 (35.7) |

| 4 | 7 (10.0) |

| Hepatic inflammatory activity | |

| 0 | 0 (0) |

| 1 | 1 (1.4) |

| 2 | 30 (42.3) |

| 3 | 39 (55.7) |

| LSM value (kPa, maean ± SD) | 11.3 ± 6.4 |

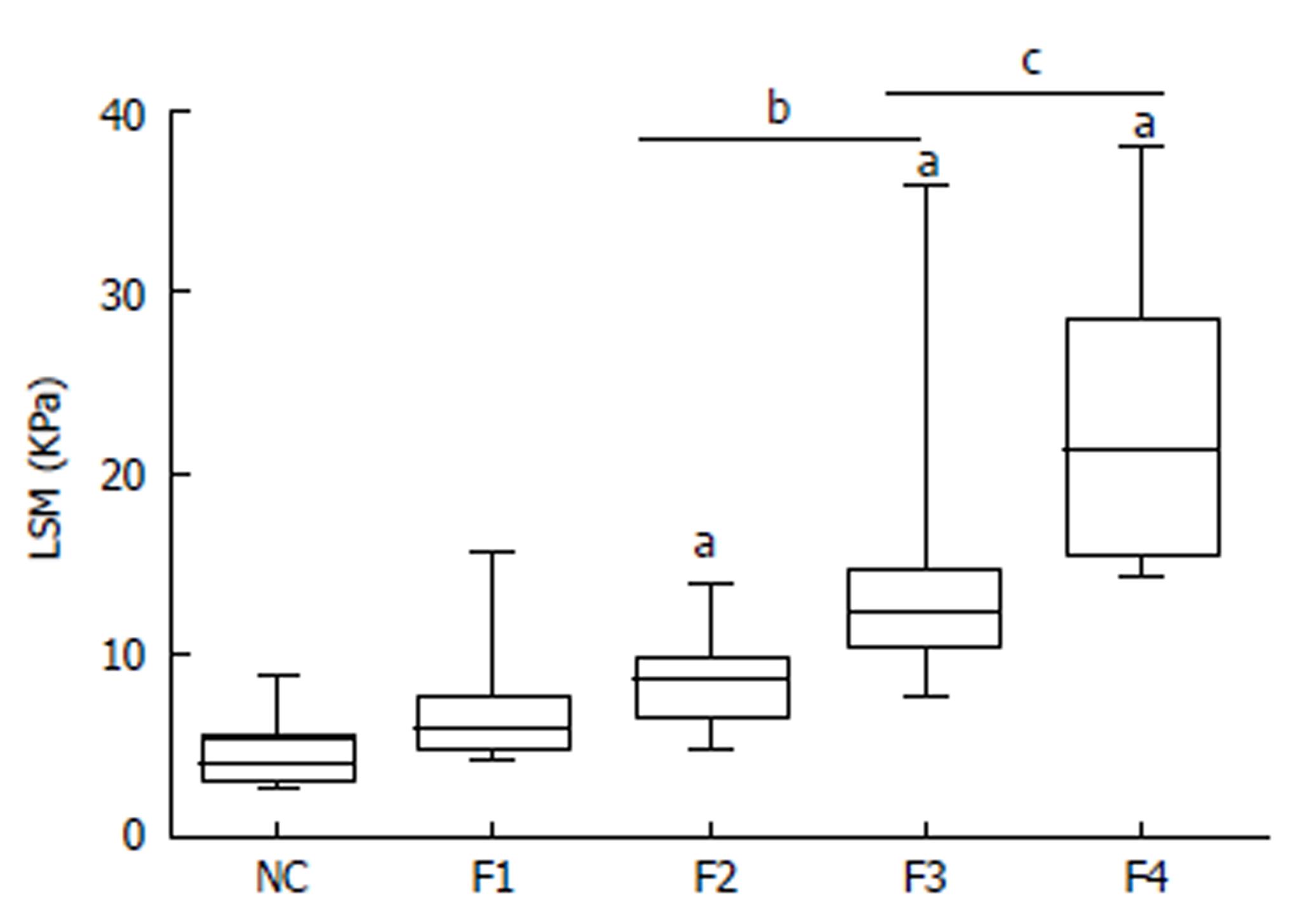

LSM was successfully performed in all patients. The mean LSM value of all AIH-PBC overlap syndrome patients was clearly higher than that of healthy normal controls (11.3 ± 6.4 kPa vs 4.3 ± 1.4 kPa, P < 0.01). LSM values for fibrosis stages F1, F2, F3, and F4 were 6.9 ± 3.4 kPa, 8.3 ± 2.0 kPa, 13.3 ± 5.5 kPa, and 22.8 ± 8.3 kPa, respectively. LSM was closely correlated with fibrosis stage (r = 0.756, P < 0.01). Patients with higher fibrosis stages usually had higher LSM values (Figure 1).

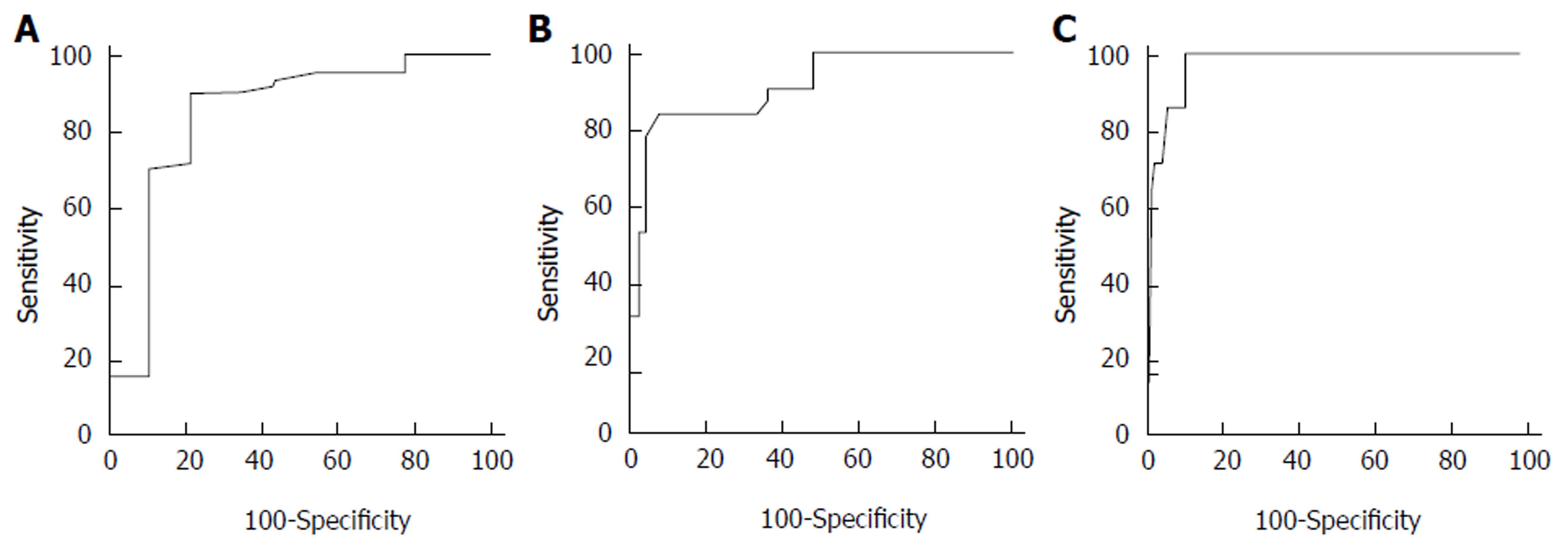

The AUROC values of LSM in detecting significant fibrosis (F ≥ 2), severe fibrosis (F ≥ 3), and cirrhosis (F4) were 0.837, 0.910, and 0.966, respectively (Figure 2). The optimal cut-off values of LSM for fibrosis stages were 6.55 pKa for F ≥ 2, 10.50 kPa for F ≥ 3, and 14.45 pKa for F4 with the highest combined sensitivity and specificity (Table 2).

| Stage | AUROC (95%CI) | Cut-off (kPa) | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | +LR | -LR |

| F ≥ 2 | 0.837 (0.729-0.914) | 6.55 | 0.902 | 0.778 | 0.965 | 0.538 | 4.06 | 0.13 |

| F ≥ 3 | 0.910 (0.817-0.965) | 10.50 | 0.844 | 0.921 | 0.900 | 0.875 | 10.69 | 0.17 |

| F = 4 | 0.966 (0.893-0.995) | 14.45 | 1.000 | 0.889 | 0.500 | 1.000 | 9.00 | 0.00 |

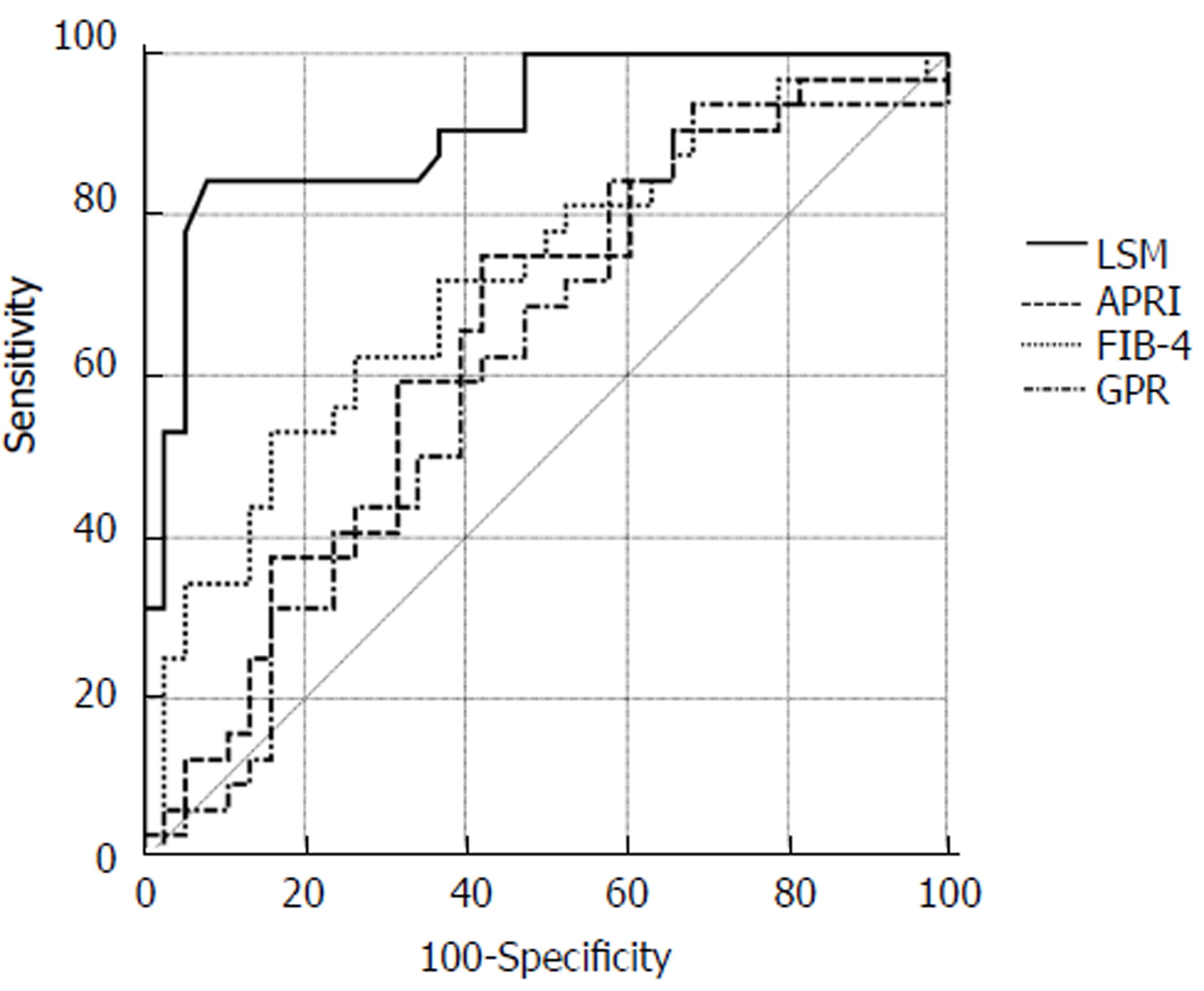

The biochemical scores FIB-4, GPR, and APRI were calculated for all patients based on their laboratory parameters. AUROCs of FIB-4, APRI, and GPR for detecting severe fibrosis (F ≥ 3) were 0.715 (95%CI: 0.594-0.816), 0.649 (0.525-0.759), and 0.616 (0.0.492-0.730), respectively. LSM was superior to FIB-4, GPR, and APRI in detecting severe fibrosis (F ≥ 3) by AUROC values (0.910 vs 0.715, P < 0.01; 0.910 vs 0.649, P < 0.01; 0.910 vs 0.616, P < 0.01, respectively) (Figure 3).

Timely and accurate assessment of the degree of liver fibrosis is crucial to the evaluation of disease progression and decision of therapeutic schedule in various chronic liver diseases[18]. LSM assessed by TE was introduced and widely used as an effective and promising non-invasive tool for assessment of liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B and C, as well as non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases[19-21]. In the current study, we found that LSM had a strong correlation with histological fibrosis stage in patients with AIH-PBC overlap syndrome, while it was significantly superior to FIB-4, GPR, and APRI scores in detecting severe fibrosis.

Our study illustrated a favorable diagnostic performance of LSM for assessing different fibrosis stages in AIH-PBC overlap syndrome. The AUROCs of LSM in detecting significant fibrosis (F ≥ 2), severe fibrosis (F ≥ 3), and cirrhosis (F4) were 0.837, 0.910, and 0.966, respectively. The cut-off values for predicting F ≥ 2, F ≥ 3, and F4 were 6.55, 10.50, and 14.45 kPa, respectively. Compared with the cut-off values reported in our recent study in patients with AIH alone, in which the optimal LSM cut-off values for predicting significant fibrosis, severe fibrosis, and cirrhosis were 6.45, 8.75, and 12.5 kPa[13], respectively, the LSM cut-off values in AIH-PBC overlap syndrome were slightly higher, especially in severe fibrosis and cirrhosis. Another study reported that the optimal LSM cut-off values for significant fibrosis, severe fibrosis, and cirrhosis were 7.3 kPa, 9.8 kPa, and 17.3 kPa, respectively, in PBC and PSC patients[22]. It seemed that the patients with AIH-PBC overlap syndrome or PBC had relatively higher LSM values than AIH patients. The major reason is probably that AIH-PBC overlap syndrome patients have a poor treatment response and rapid disease progression. However, in a meta-analysis comprised of 22 studies and 4430 patients with different etiologies of liver disease, the estimated LSM cut-off values were 7.71 kPa for F ≥ 2 and 15.08 kPa for F4[23]. Our findings are similar to these results, indicating that etiology of liver disease has no significant effect on LSM assessment.

LSM by TE had a favorable diagnostic performance in evaluating liver fibrosis as a non-invasive method. Compared with APRI and FIB-4, which are widely used as non-invasive serologic methods, LSM showed better accuracy in detecting liver fibrosis[6,24]. In the current study, we also found that LSM was significantly superior to FIB-4 and APRI in detecting severe fibrosis in AIH-PBC overlap syndrome patients, which is consistent with our previous result. In a recent study, GPR had exhibited a better accuracy than APRI and FIB-4 in detecting liver fibrosis in CHB patients[17]. Here, we found that GPR had a similar diagnostic performance for detecting severe fibrosis to APRI and FIB-4 scores but was inferior to LSM.

The major limitation of our study was the small patient sample size due to the low prevalence of AIH-PBC overlap syndrome. Larger studies are needed to confirm these results.

In conclusion, LSM by TE is an accurate and reliable non-invasive method in evaluating liver fibrosis in patients with AIH-PBC overlap syndrome. LSM is significantly superior to APRI, GPR, and FIB-4 scores for detecting severe fibrosis.

Transient elastography (TE) can reliably stage liver fibrosis via liver stiffness measurement (LSM) in chronic liver disease. However, the accuracy of TE for assessment of liver fibrosis in patients with autoimmune hepatitis-primary biliary cholangitis (AIH-PBC) overlap syndrome is still unclear.

It is important to identify non-invasive markers of liver fibrosis to predict disease progression.

We evaluated the performance and usefulness of TE for detection of fibrosis in these patients and compared TE with other non-invasive diagnostic tools.

The diagnostic accuracy of LSM for the prediction of fibrosis stages was calculated using a receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve. Optimal LSM cut-off values for F2-4 fibrosis were determined based on the highest combined sensitivity and specificity.

TE can accurately detect hepatic fibrosis as a non-invasive method in patients with AIH-PBC overlap syndrome.

For the first time, the current study evaluated TE as a non-invasive assessment of liver fibrosis in patients with AIH-PBC overlap syndrome and demonstrated that it was a reliable tool that was superior to serum biomarker scores for predicting severe fibrosis.

The impact of hepatic inflammation on LSM values was not analyzed due to the relatively small number of patients in each subgroup. Larger studies are needed to confirm these results.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Saez-Royuela F S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Lee YA, Wallace MC, Friedman SL. Pathobiology of liver fibrosis: a translational success story. Gut. 2015;64:830-841. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: 1] [Cited by in Crossref: 601] [Cited by in RCA: 682] [Article Influence: 68.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Alvarez F, Berg PA, Bianchi FB, Bianchi L, Burroughs AK, Cancado EL, Chapman RW, Cooksley WG, Czaja AJ, Desmet VJ. International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group Report: review of criteria for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1999;31:929-938. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: 1] [Cited by in Crossref: 2003] [Cited by in RCA: 1955] [Article Influence: 75.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Vierling JM. Autoimmune Hepatitis and Overlap Syndromes: Diagnosis and Management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:2088-2108. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: 2] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Manns MP, Lohse AW, Vergani D. Autoimmune hepatitis--Update 2015. J Hepatol. 2015;62:S100-S111. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: 1] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 245] [Article Influence: 24.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: The diagnosis and management of patients with primary biliary cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2017;67:145-172. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: 1] [Cited by in Crossref: 950] [Cited by in RCA: 843] [Article Influence: 105.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Castéra L, Vergniol J, Foucher J, Le Bail B, Chanteloup E, Haaser M, Darriet M, Couzigou P, De Lédinghen V. Prospective comparison of transient elastography, Fibrotest, APRI, and liver biopsy for the assessment of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:343-350. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: 2] [Cited by in Crossref: 1796] [Cited by in RCA: 1832] [Article Influence: 91.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rockey DC, Caldwell SH, Goodman ZD, Nelson RC, Smith AD; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Liver biopsy. Hepatology. 2009;49:1017-1044. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: 1] [Cited by in Crossref: 1449] [Cited by in RCA: 1530] [Article Influence: 95.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Sandrin L, Fourquet B, Hasquenoph JM, Yon S, Fournier C, Mal F, Christidis C, Ziol M, Poulet B, Kazemi F. Transient elastography: a new noninvasive method for assessment of hepatic fibrosis. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2003;29:1705-1713. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: 1] [Cited by in Crossref: 1967] [Cited by in RCA: 1913] [Article Influence: 87.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wang Q, Selmi C, Zhou X, Qiu D, Li Z, Miao Q, Chen X, Wang J, Krawitt EL, Gershwin ME. Epigenetic considerations and the clinical reevaluation of the overlap syndrome between primary biliary cirrhosis and autoimmune hepatitis. J Autoimmun. 2013;41:140-145. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: 1] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chazouillères O, Wendum D, Serfaty L, Montembault S, Rosmorduc O, Poupon R. Primary biliary cirrhosis-autoimmune hepatitis overlap syndrome: clinical features and response to therapy. Hepatology. 1998;28:296-301. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: 2] [Cited by in Crossref: 506] [Cited by in RCA: 466] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Montano-Loza AJ, Thandassery RB, Czaja AJ. Targeting Hepatic Fibrosis in Autoimmune Hepatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:3118-3139. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: 1] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Park Y, Cho Y, Cho EJ, Kim YJ. Retrospective analysis of autoimmune hepatitis-primary biliary cirrhosis overlap syndrome in Korea: characteristics, treatments, and outcomes. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2015;21:150-157. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited in This Article: 1] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Xu Q, Sheng L, Bao H, Chen X, Guo C, Li H, Ma X, Qiu D, Hua J. Evaluation of transient elastography in assessing liver fibrosis in patients with autoimmune hepatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32:639-644. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: 2] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bedossa P, Poynard T. An algorithm for the grading of activity in chronic hepatitis C. The METAVIR Cooperative Study Group. Hepatology. 1996;24:289-293. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: 1] [Cited by in Crossref: 2860] [Cited by in RCA: 3047] [Article Influence: 105.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wai CT, Greenson JK, Fontana RJ, Kalbfleisch JD, Marrero JA, Conjeevaram HS, Lok AS. A simple noninvasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:518-526. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: 1] [Cited by in Crossref: 2762] [Cited by in RCA: 3193] [Article Influence: 145.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sterling RK, Lissen E, Clumeck N, Sola R, Correa MC, Montaner J, S Sulkowski M, Torriani FJ, Dieterich DT, Thomas DL. Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology. 2006;43:1317-1325. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: 1] [Cited by in Crossref: 2633] [Cited by in RCA: 3401] [Article Influence: 179.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lemoine M, Shimakawa Y, Nayagam S, Khalil M, Suso P, Lloyd J, Goldin R, Njai HF, Ndow G, Taal M. The gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase to platelet ratio (GPR) predicts significant liver fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic HBV infection in West Africa. Gut. 2016;65:1369-1376. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited in This Article: 2] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 267] [Article Influence: 29.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Trautwein C, Friedman SL, Schuppan D, Pinzani M. Hepatic fibrosis: Concept to treatment. J Hepatol. 2015;62:S15-S24. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: 1] [Cited by in Crossref: 439] [Cited by in RCA: 502] [Article Influence: 50.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Jia J, Hou J, Ding H, Chen G, Xie Q, Wang Y, Zeng M, Zhao J, Wang T, Hu X. Transient elastography compared to serum markers to predict liver fibrosis in a cohort of Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:756-762. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: 1] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ziol M, Handra-Luca A, Kettaneh A, Christidis C, Mal F, Kazemi F, de Lédinghen V, Marcellin P, Dhumeaux D, Trinchet JC. Noninvasive assessment of liver fibrosis by measurement of stiffness in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2005;41:48-54. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: 1] [Cited by in Crossref: 1090] [Cited by in RCA: 1067] [Article Influence: 53.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yoneda M, Yoneda M, Fujita K, Inamori M, Tamano M, Hiriishi H, Nakajima A. Transient elastography in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Gut. 2007;56:1330-1331. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: 1] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Corpechot C, El Naggar A, Poujol-Robert A, Ziol M, Wendum D, Chazouillères O, de Lédinghen V, Dhumeaux D, Marcellin P, Beaugrand M. Assessment of biliary fibrosis by transient elastography in patients with PBC and PSC. Hepatology. 2006;43:1118-1124. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: 1] [Cited by in Crossref: 319] [Cited by in RCA: 316] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Stebbing J, Farouk L, Panos G, Anderson M, Jiao LR, Mandalia S, Bower M, Gazzard B, Nelson M. A meta-analysis of transient elastography for the detection of hepatic fibrosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:214-219. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: 1] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | E Anastasiou O, Büchter M, A Baba H, Korth J, Canbay A, Gerken G, Kahraman A. Performance and Utility of Transient Elastography and Non-Invasive Markers of Liver Fiibrosis in Patients with Autoimmune Hepatitis: A Single Centre Experience. Hepat Mon. 2016;16:e40737. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited in This Article: 1] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |