Published online Dec 7, 2018. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i45.5144

Peer-review started: October 15, 2018

First decision: October 23, 2018

Revised: November 5, 2018

Accepted: November 16, 2018

Article in press: November 16, 2018

Published online: December 7, 2018

Processing time: 62 Days and 9.4 Hours

To identify short-term and oncologic outcomes of pelvic exenterations (PE) for locally advanced primary rectal cancer (LAPRC) in patients included in a national prospective database.

Few studies report on PE in patients with LAPRC. For this study, we included PE for LAPRC performed between 2006 and 2017, as available, from the Rectal Cancer Registry of the Spanish Association of Surgeons [Asociación Española de Cirujanos (AEC)]. Primary endpoints included procedure-associated complications, 5-year local recurrence (LR), disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS). A propensity-matched comparison with patients who underwent non-exenterative surgery for low rectal cancers was performed as a secondary endpoint.

Eight-two patients were included. The mean age was 61.8 ± 11.5 years. More than half of the patients experienced at least one complication. Surgical site infections were the most common complication (abdominal wound 18.3%, perineal closure 19.4%). Thirty-three multivisceral resections were performed, including two hepatectomies and four metastasectomies. The long-term outcomes of the 64 patients operated on before 2013 were assessed. The five-year LR was 15.6%, the distant recurrence rate was 21.9%, and OS was 67.2%, with a mean survival of 43.8 mo. R+ve resection increased LR [hazard ratio (HR) = 5.58, 95%CI: 1.04-30.07, P = 0.04]. The quality of the mesorectum was associated with DFS. Perioperative complications were independent predictors of shorter survival (HR = 3.53, 95%CI: 1.12-10.94, P = 0.03). In the propensity-matched analysis, PE was associated with better quality of the specimen and tended to achieve lower LR with similar OS.

PE is an extensive procedure, justified if disease-free margins can be obtained. Further studies should define indications, accreditation policy, and quality of life in LAPRC.

Core tip: Pelvic exenteration (PE) for locally advanced primary rectal cancer (LAPRC) is associated with high rates of perioperative adverse events, but the survival benefit obtained when R-ve margins are achieved outweighs this risk. In low LAPRC, PE achieved better pathologic outcomes, resulting in a trend towards reduced LR compared with non-exenterative procedures.

- Citation: Pellino G, Biondo S, Codina Cazador A, Enríquez-Navascues JM, Espín-Basany E, Roig-Vila JV, García-Granero E, on behalf of the Rectal Cancer Project. Pelvic exenterations for primary rectal cancer: Analysis from a 10-year national prospective database. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(45): 5144-5153

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v24/i45/5144.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i45.5144

Colorectal cancer is the fourth cause of cancer-related death in United States[1]. A recent analysis of the SEER programme concerning age-specific annual percent change in incidence rates from 2000 to 2013 showed that the incidence of rectal cancer and advanced disease has slightly decreased, but it is less than that of colon cancer[2]. Five-year survival is influenced by tumour stage, ranging from 90% in cancer confined to the primary site and 71% in those with local node involvement to 14% in Stage IV[3]. One-third of newly diagnosed rectal cancers in the United Kingdom will be locally advanced at the time of diagnosis, accounting for more than 4600 cases of cancer per year[4,5].

Recent advances in the multimodal management of patients with rectal cancer invading local structures have led to an increase in the rate of patients amenable to receive surgery along the anatomical planes after neoadjuvant treatment. Nevertheless, a relatively high number of patients might still be found with tumours invading surrounding organs[4].

Pelvic exenteration (PE) is a technically demanding procedure involving “en-bloc” excision of the rectum and adjacent invaded organs, aiming at obtaining disease-free resection margins. Over time, contraindications to such a demolitive approach have been gradually reduced as a result of perioperative patient conditioning, increased surgical experience, and postoperative multidisciplinary management[5-7]. Surgery beyond the total mesorectal excision (TME) plane and involving sacrifice of other pelvic organs for locally recurrent or advanced rectal cancer has been analogous to a “sarcoma-like” procedure[6,8-10], during which several surgical teams and specialties need to be involved. PE for rectal cancer brings higher risks of complications, ranging from 25% to 42%[5,8,11], with studies reporting higher rates when PE for other-than-rectal cancers is included[12]. The high incidence of complications is downplayed by the survival benefits obtained by excision of the pelvic mass with microscopically negative margins (R0)[7,8,12-14]. Few studies have focused on the outcomes of PE in locally advanced primary rectal cancer (LAPRC), although an increasing number of patients are being offered this extensive procedure. A recent study of the PelvEx Collaborative found that the median life expectancy after curative PE for LAPRC surpasses 40 mo, but median survival after resections with macroscopically involved margins drops to less than one year[14].

As part of a national quality improvement programme in the treatment of rectal cancer, the Spanish Association of Surgeons [“Asociación Española de Cirujanos” (AEC)] started an online database[15] in which all primary rectal cancers were prospectively included on a voluntary basis. Data on patients undergoing PE were also recoded.

The aims of this study are to assess the short- and long-term outcomes of PE for primary LAPRC in patients included in the AEC registry and to compare the oncologic results of PE with a matched group of patients treated with non-exenterative TME during the study timeframe.

This study complies with the STROBE statement for observational studies[16] (Flowchart in Supplementary Figure 1; checklist available as uploaded STROBE Statement). In 2006, the AEC established a national audit project to improve the outcomes of rectal cancer surgery. The project was named “Viking” because it was inspired by the project from Norway[17] and followed the same principles[18]. Between 2006 and 2017, 105 Spanish hospitals joined the online registry, with over 18000 patients included. The aim of this study was to assess morbidity and long-term outcomes of PE for LAPRC.

We included patients who underwent PE for LAPRC between 2006 and 2017. The patients were only included if they underwent surgery with curative intent. For the survival analysis, only patients with a minimum follow up of 5 years were evaluated.

The patients who were unfit for surgery, those who underwent palliative surgery, those diagnosed with other malignancies besides colonic malignancies, and those with unsatisfactory information were excluded from the analysis.

The primary aims of this study were: (1) short-term morbidity and mortality of PE for LAPRC; (2) overall 5-year local recurrence (LR), disease-free survival (DFS), and overall survival (OS). Secondary outcomes included oncologic outcomes after PE compared with patients in the registry who underwent TME for distal rectal cancer surgery during the same timeframe, with a propensity-matched analysis.

The online database allows the investigators to classify the type of intervention performed. Only “PE” interventions were included in the analysis and consisted of either posterior (removal of rectum, internal genital organs in female) or total (removal of rectum and bladder, in male and female). Indications for surgery and perioperative management were not standardized before starting the study, although most centres followed the agreed-upon criteria[19].

Thirty-day complications were collected, and the responsible collaborator at each centre updated the data on oncologic outcome yearly[18,20].

Specimen assessment and reporting have been previously described[18,20,21]. Briefly, margins were considered tumour-free if no microscopic involvement was seen at pathology. The circumferential resection margin was considered involved if cancer cells were found 1 mm or less from the margin[20]. The quality of the mesorectum and abdominoperineal excision was scored using three grades as described by others[20-23].

LR was defined as a mass near or at the same place as the original tumour, after a period of time in which the tumour was not detected. LR was included only if an imaging exam proved the recurrence combined with raised CEA.

DFS was defined as time to develop a distant disease relapse that was not present or suspected at primary surgery. Distant metastases included para-aortic and inguinal nodes.

OS was defined as time to death for any reason.

Detailed definitions and scope of the registry have been previously reported[15,18,20] (http://www.aecirujanos.es/images/stories/recursos/secciones/coloproctologia/2015/proyecto_vikingo/documentos/definiciones_proyecto_vikingo.pdf).

For the secondary aims, the group that was propensity matched with PE included all patients from the database with low rectal cancer who underwent TME surgery with abdominoperineal excision, extralevator abdominoperineal excision, and low anterior resection between March 2006 and December 2013.

Continuous variables are reported as the means ± standard deviations (SD), and categorical variables are reported as the numbers with percentages (%).

For the secondary aims, the propensity-matched analysis for complications was carried out based on the following variables: American Society of Anesthesiologists’ (ASA) score, neoadjuvant treatment, and pT stage. Only patients with cancer of the lower third of the rectum (0-6 cm from anal verge) who underwent curative TME surgery were included.

Categorical variables were compared with Fisher’s exact test and Chi square test as appropriate, whereas continuous variables were compared with Mann-Whitney U test.

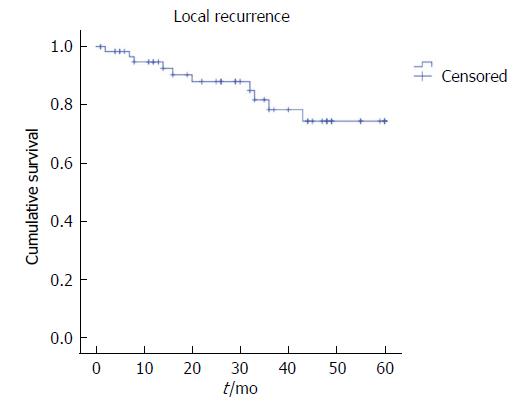

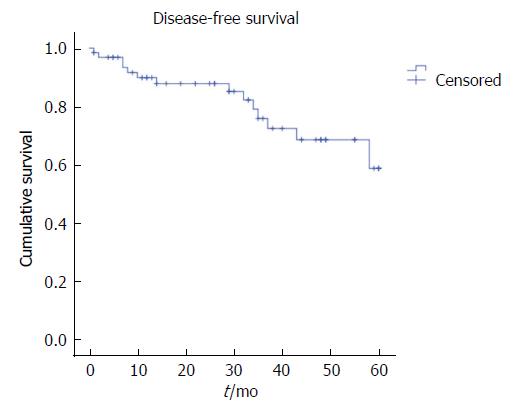

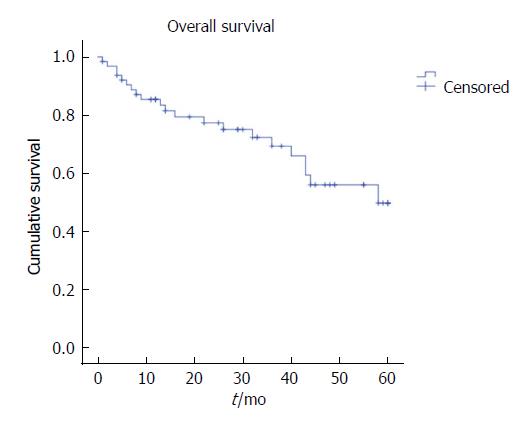

Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated to assess 5-year survival, and log rank test was used for comparisons when applicable. Cox regression analysis was used to identify predictors of LR, DFS, and OS, including the following variables: resection margin status, quality of mesorectum, neoadjuvant treatment, adjuvant treatment, and perioperative complications. The results are reported as hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). HR > 1 is associated with increased risk. Patients lost at follow up were classified as censored.

P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 24.0.0; IBM SPSS statistics, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY) was used for the descriptive analyses.

We analysed data on 82 patients undergoing PE for LAPRC in 33 hospitals, with a mean number of procedures per hospital of 2.5 ± 3.1 overall.

Demographics and perioperative features are summarized in Table 1. The mean age of the patients was 61.8 ± 11.5 years, 65.9% were men, 34.1% were women, and 45.1% were classified as ASA ≥ III. Most patients were staged as MRcT4 [T4 with magnetic resonance (MR)] and had extensive nodal involvement. The tumour was located in the proximal third of the rectum (15-11 cm) in 18 (22%) patients, in the middle third (10-7 cm) in 31 (37.8%) patients, and in the distal third (6-0 cm) in 33 (40.2%) patients. Seven patients underwent PE with concomitant distant metastases. Neoadjuvant treatment was offered to 72% of patients and included radiotherapy in 93% of them. No data were available concerning time to surgery after treatment.

| Variable | Value |

| Age, yr | 61.8 (11.5) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 54 (65.9) |

| Female | 28 (34.1) |

| ASA score | |

| I | 3 (3.7) |

| II | 42 (51.2) |

| III | 33 (40.2) |

| IV | 4 (4.9) |

| Obstruction | 5 (6.1) |

| MR T | |

| T3 | 13 (15.9) |

| T4 | 56 (68.3) |

| Missing | 13 (15.9) |

| MR N | |

| N0 | 11 (13.4) |

| N1 | 24 (29.3) |

| N2 | 35 (42.7) |

| Missing | 12 (14.6) |

| Sphincters involved | 22 (26.8) |

| Metastasis at presentation | 7 (8.5) |

| Neoadjuvant treatment | 59 (72) |

| Long course RT | 3 (5) |

| Long course CRT | 41 (69.5) |

| CxT | 4 (6.8) |

| Short Course RT | 4 (6.8) |

| CxT followed by RT | 7 (11.9) |

| Adjuvant treatment | 54 (65.9) |

| CRT | 6 (11.1) |

| CT | 48 (88.9) |

| Perioperative transfusions, n | 3.4 (2) |

| Anastomosis | 15 (18.3) |

| Synchronous metastasis resected | 4 (6.8) |

Fifty-four (65.9%) patients received postoperative chemotherapy, which was associated with radiotherapy in 6 (11.1%). An anastomosis was attempted in 15 patients. In the latter group, eight patients received preoperative radiotherapy and postoperative treatment was given in nine, including radiotherapy in two.

Thirty-three multivisceral resections were performed, including two hepatectomies and four metastasectomies. One liver lesion was treated with radiofrequency ablation. One patient received peritonectomy.

Perioperative death rates did not exceed 2.5%. More than half of the patients experienced at least one complication, and 10% required reoperation. Intra-abdominal septic complications occurred in 10% of the patients.

Surgical site infections affected the abdominal wound in 18.3% and the perineal closure in 19.4% of those who did not receive an anastomosis. Short-term outcomes are reported Table 2.

| Variable | Value |

| Complications, any | 45 (54.9) |

| Reoperation | 8 (9.8) |

| Perioperative death | 2 (2.4) |

| Sepsis | 4 (4.9) |

| Abdominal Surgical Site Infection | 15 (18.3) |

| Abdominal hernia | 2 (2.4) |

| Perineal Wound Complications | 13/67 (19.4) |

| Intra-abdominal septic complications | 8 (9.8) |

| Injury to hollow viscera | 2 (2.4) |

| Ileus | 9 (11) |

| Urinary tract complications | 9 (11) |

| Pulmonary complications | 8 (9.8) |

| Neurological complications | 2 (2.4) |

| Multiorgan failure | 2 (2.4) |

| CVC infection | 2 (2.4) |

| Acute kidney failure | 2 (2.4) |

Table 3 depicts pathological outcomes. Most cancers were pT4b (36.6%), with significant reduction of cN2 rate in favour of pN0 (40.2%) and pN1 (20.7%). The mean number of isolated nodes was well over 12 and rarely harboured cancer (in 25.6%). Nineteen patients (23.2%) received R+ve resection - one with both circumferential and distal margins affected.

| Variable | Value |

| pT | |

| Tx | 2 (2.4) |

| T0 | 1 (1.2) |

| T2 | 2 (2.4) |

| T3a,b | 6 (7.3) |

| T3c,d | 13 (15.9) |

| T4a | 27 (32.9) |

| T4b | 30 (36.6) |

| Missing | 1 (1.2) |

| pN | |

| Nx | 25 (30.5) |

| N0 | 33 (40.2) |

| N1 | 17 (20.7) |

| N2 | 6 (7.3) |

| Missing | 1 (1.2) |

| Nodes isolated | 15.5 (10.6) |

| Positive nodes | 1.1 (0.4) |

| Resection margins involved | 19 (23.2) |

| Response to neoadjuvant treatment (n = 59) | |

| Complete | 1 (1.7) |

| Islands of tumour cells | 1 (1.7) |

| Predominantly fibrotic | 20 (33.9) |

| Predominantly tumour nests | 21 (35.6) |

| No response | 12 (20.3) |

| Missing | 4 (6.8) |

| Quality of mesorectum[20-23] | |

| Good/complete | 61 (74.4) |

| Partially good/near complete | 9 (11) |

| Bad/incomplete | 8 (9.8) |

| Missing | 4 (4.9) |

Twenty percent of patients did not have any response to preoperative neoadjuvant treatment, one patient had complete pathological response (1.7%), and the remaining patients had a different spectrum of response (detailed in Table 3). The quality of mesorectum was classified as “good” (complete)[20-23] in 74.4% of patients.

For the purpose of long-term outcomes, we excluded 18 patients who received PE after 2013, thereby analysing 64 patients.

The five-year LR was 15.6%, the distant recurrence rate was 21.9%, and OS was 67.2%, with a mean survival of 43.8 mo (Figures 1-3). Oncologic outcomes tended to be worse in pN+ patients in all dimensions, although these differences did not reach statistical significance.

The Cox regression analysis identified R+ve resection to increase the risk of LR (HR = 5.58, 95%CI: 1.04-30.07, P = 0.04), and partially good or bad quality mesorectum to predict shorter DFS (HR = 4.37, 95%CI: 1.02-18.65, P = 0.04, and HR = 6.29, 95%CI: 1.2-32.94, P = 0.03, respectively). Perioperative complications were independent predictors of shorter survival (HR = 3.53, 95%CI: 1.12-10.94, P = 0.03).

The propensity match analysis identified 51 patients who received either PE (n = 26) or non exenterative TME (n = 25) for primary adenocarcinoma of the lower rectum. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 4. TME patients more frequently received an anastomosis (3.8% vs 80%, PE vs TME, P < 0.001) and were less likely to need transfusions (P = 0.035). PE was associated with better quality of the specimen, consisting of fewer R+ve resections and higher rates of good quality mesorectum.

| Pelvic exenteration n = 26 | Non-exenterative total mesorectal excision n = 25 | P value | |

| Male | 18 (58.1) | 13 (52) | 0.208 |

| Age at surgery | 63.1 ± 8.6 | 62.3 ± 13.7 | 0.794 |

| ASA score | 0.957 | ||

| I | 1 (3.8) | 1 (4) | |

| II | 11 (42.3) | 11 (44) | |

| III | 12 (46.2) | 12 (48) | |

| IV | 2 (7.7) | 1 (4) | |

| Obstruction | 1 (3.8) | 0 | 0.322 |

| Neoadjuvant treatment | 21 (80.8) | 21 (84) | 0.762 |

| Adjuvant treatment | 19 (73.1) | 21 (84) | 0.343 |

| Anastomosis | 1 (3.8) | 20 (80) | < 0.001a |

| T Stage | 0.913 | ||

| pT3a,b | 1 (3.8) | 1 (4) | |

| pT3c,d | 6 (23.1) | 6 (24) | |

| pT4a | 7 (26.9) | 7 (28) | |

| pT4b | 11 (42.3) | 11 (44) | |

| pTx | 1 (3.8) | 0 | |

| Resection margins involved | 5 (19) | 7 (28) | 0.426 |

| Perforation | 2 (7.7) | 4 (16) | 0.357 |

| Transfusions | 2.6 ± 2.4 | 1.12 ± 2.4 | 0.035a |

| Quality of the mesorectum[20-23] | 0.351 | ||

| Good/Complete | 16 (69.6) | 13 (52) | |

| Partially good/Nearly complete | 4 (17.4) | 8 (32) | |

| Bad/Incomplete | 3 (13) | 4 (16) |

LR tended to be lower in patients who received PE compared with TME (P = 0.34) (Supplementary Figure 2), with comparable OS (P = 0.96) (Supplementary Figure 3).

The present study showed good survival following PE for LAPRC in a cohort of patients included in a national prospective database. The procedure brings a significant risk of complications, occurring in 50% of patients, and non-negligible perioperative death rates. Pathological outcomes and long-term survival justify such extensive operations. Negative resection margins were achieved in 76.8% of patients and were associated with reduced rates of LR. Complications impaired 5-year survival. Comparing patients who underwent PE vs TME for low rectal cancer, PE showed a trend towards better specimen quality and lower rates of R+ve resection and tended to have longer LR-free intervals.

Since the first description of PE for gynaecologic cancer in 1948[6,24], the procedure has been adopted with increasing success rates in patients with rectal cancer[8,12-14,25-27]. The PE of colorectal interest involves “en bloc” resection of the cancer and of the surrounding structures/organs, namely, the rectum, distal colon, internal reproductive organs, draining lymph in posterior PE (also known as composite resections) or bladder, lower ureters, rectum, distal colon, sacrum, reproductive organs, draining lymph nodes and peritoneum in total PE[6,28].

Perioperative complications in our study were in line with rates reported in the literature. A systematic review[29] with 23 studies found that postoperative complications ranged between 37% and 100% (median 57%) and that perioperative mortality ranged between 0% and 25% (median 2.2%) after PE for LAPRC and recurrent cancer. The studies including all types of pelvic malignancies reported a complication rate as high as 64%[6]. In more recent series, complications occurred in 27.7% to 42.2% of patients who underwent PE for LAPRC[5,11,13,26]. Irrespective of ASA score, the rate of patients developing serious complications might be similar to that observed after TME anterior resection[11,30]. In our series, the rate of patients who developed complications needing reintervention was 10%. Surgeons willing to set up units dedicated to PE need to be prepared to long postoperative stays and significant morbidity, even in experienced hands[19]; early diagnosis and proactive management will be important to reduce their effects. Hsu et al[31] have discarded any influence of perioperative complications on survival after LAPRC surgery, but in our series, complications were independently associated with shorter life expectancy (HR = 3.53, 95%CI: 1.12-10.94, P = 0.03). These findings need to be carefully evaluated in the context of surgeon-specific outcomes[32] and learning curves associated with PE[33], and any attempt should be made to reduce complications, e.g., being very selective in performing anastomosis and including a dedicated anaesthetist in the multidisciplinary team to allow for patient optimization[5,19,30].

The rate of R+ve resection in our study was similar to other reports but likely improvable. Combined with the quality of the excised specimen, it represents a reliable surrogate marker for LR and survival after PE[6,7,8,25]. The number of lymph nodes harvested in specimens from patients who underwent neoadjuvant treatment is matter of debate in the vast majority of cases, and the PelvEx collaborative found it to be significantly associated with survival[13]. The mean number of nodes isolated from the specimen was higher than 12, which is the minimum acceptable number for TME. However, in this series, the effect on oncologic outcome was less obvious when comparing pN+ and pN- patients. Given the importance of pT and pN status in colorectal cancer[34], this issue needs to be further investigated in LAPRC. We confirmed that R status was an independent predictor of LR, which was impaired by five-fold in the event of positive resection margins. Statistical significance was maintained even if we observed a wide CI; cautious interpretation is needed, but the clinical relevance is unquestioned. Kontovounisios et al[5] analysed the performance of dedicated PE MDT at a single unit, and they achieved an R0 rate of 93% by the last year of their report. Interestingly, there was an inverse relation between the number of referrals (increasing over time) and the relative number of procedures performed (decreasing). This outcome resulted from better patient selection and better surgical timing in the context of multidisciplinary treatment. Other series reported rates of R+ve resections similar to the one in our analysis[11,13].

OS after PE for LAPRC is intertwined with the radicality of resection and recurrence[8,13]. The largest international, prospective study on PE for LAPRC included 1291 patients from 14 countries and showed a median 5-year survival of 43 months. The rate of patients who were alive at 5-year follow up from our database was 67.2%, which is at or above the upper limit of the ranges reported in the literature[6,12,26,30]. Reasons that could justify this finding include surgery probably not being offered to patients who might have been operated on in other centres with a more aggressive policy, e.g., patients with pelvic bone involvement. According to the beyond TME collaborative[19], only poor performance status/medically unfit patients, bilateral sciatic nerve involvement and circumferential bone involvement should be considered absolute contraindications to surgery. A more conservative approach in patients from the database appears to be a reasonable option. Another reason could be early referral to hospitals with dedicated units. Lastly, individual investigators might have decided not to include patients with more complex disease and predictable poorer outcomes.

The ideal management of patients with LAPRC arising in the lower rectum is still a matter of debate. Given the excellent results in terms of tumour clearance and quality of life achieved with TME, mutilating approaches such as PE are deemed overtreatment in many patients. However, this part of the rectum is associated with higher rates of complications, and optimizing the outcomes of surgery for LAPRC of the lower third is still matter of research[35,36]. After adjusting two groups of patients with a propensity-matched analysis, we observed a trend towards better specimen quality and increased LR-free intervals with similar OS. These findings need further evaluation and should be considered when planning future studies on PE or involving low rectal cancers.

This study has several limitations, and our findings should be interpreted with caution. Voluntary inclusion of patients in registries might account for a selection bias, even if they are prospective. The analysis covered a 10-year timeframe and included patients operated on different centres. Multidisciplinary patient management is crucial in PE[5], and variability between hospitals could not be removed. However, there are no universally agreed-upon guidelines to indicate or contraindicate PE in LAPRC, despite the latest available beyond-TME Collaborative position paper, which advocated the need for further research on the topic as a matter of priority[19]. No validation of the data was planned. LR was diagnosed by raising CEA associated with imaging proving recurrence, and this might have underestimated the actual incidence. Quality of life was not available in this study. Health-related quality of life and social function are of paramount importance in patients who are candidates for PE and should be considered an important endpoint of LARC surgery. The stressful experience that patients and families go through after receiving a diagnosis and when they are forced to face an advanced and aggressive disease is made even more difficult when the perspectives of the necessity of a definitive stoma (sometimes more than one) are considered. However, no dedicated questionnaires or assessments have been proposed and validated in this group of patients and should therefore be considered a research priority.

This study has strengths. Limited series of PE for LAPRC have been reported, and the findings described herein represent the second largest study with 5-year follow up available after the PelvEx Collaborative study. We suggested that patients with LAPRC of the lower third might benefit from a more aggressive surgical approach, and future studies could be designed to confirm the survival advantage in this group of patients. Some centres advocated PE in patients with liver metastases. The numbers were too small to conduct sub-analyses, and results could be misleading. Interestingly, distant metastases are usually a contraindication to PE in most referral centres[5]. As per the available position paper, LAPRC with metastases amenable to resection could benefit from PE, on the condition that a dedicated MDT agrees to the indication. In agreement with the statements of the beyond TME Collaborative[19], the outcomes of PE should be separately reported, and our manuscript only included this homogeneous group of patients.

PE is an extensive procedure with significant rate of perioperative adverse events. The analysis of a national database on LAPRC treated with PE over 10 years confirmed the survival benefit of the procedure, which overwhelms the morbidity and mortality associated with it. The rates of LR, DFS and OS were in line with most of the reported studies, but any effort should be made to improve these results (e.g., via centralization, adherence to prospective registries and auditing, dedicated training). Disease-free resection margins (R0) comprise the aim of surgery, as they predict LR. PE should be carried out in dedicated units under the care of MDT to reduce or promptly treat complications, which impair long-term survival.

Compared with non-exenterative TME surgery, PE was associated with longer disease-free intervals and achieved similar OS in patients with LAPRC for low rectal cancer.

Further studies are needed to clarify patient selection pathways and referral centre accreditation policies, and to assess quality of life after PE.

Colorectal cancer is the fourth cause of death caused by cancer according to reports from the United States. Up to 33% of rectal cancers might present as locally advanced, requiring multidisciplinary approaches. Pelvic exenteration (PE) combined with multimodal treatment has resulted in increased survival in this population of patients, but there remains a need for further reports in the literature concerning the management of patients with primary locally advanced rectal cancer.

Previous studies suggested that an aggressive approach, with surgery combined with other treatment modalities, might confer good outcome in terms of tumour clearance and survival in locally advanced primary rectal cancer (LAPRC). Few reports have been published detailing the outcome of nationwide databases.

This study aimed to investigate the outcome of PE for primary rectal cancer in patients included in the National Spanish Association of Surgeons Rectal Cancer Registry.

This is a retrospective, observational study drafted according to the STROBE statement. Patients who underwent PE for LAPRC between 2006 and 2017 and who were registered in the Spanish Registry of Rectal Cancer of the Spanish Association of Surgeons were included if surgery was performed with curative intent and if 5-year follow up had been completed.

Short-term morbidity and mortality of the procedure and 5-year oncologic outcome represented the primary aims of this study. Secondary aims included a comparison of outcomes with a matched group of patients from the registry who underwent non-exenterative surgery for low rectal cancer during the same time frame.

PE were associated with perioperative mortality in approximately 2.5% of patients, and perioperative morbidity was common. More than 50% of patients had at least one complication, which required reoperation in 10%. Up to 10% of patients suffered from intra-abdominal septic complication. Wound-associated complications at the perineum were common, almost reaching 20%. The rate of resections with margins that involved tumours was 23%, and good quality of the mesorectum was achieved in 74% of specimens.

Oncologic outcome was acceptable, with good life expectancy provided a free-free resection margin had been achieved. An involved margin was independently associated with increased risk of local recurrence [hazard ratio (HR) = 5.58, 95%CI: 1.04-30.07, P = 0.04]. Survival was impaired by perioperative complications [HR = 3.53, 95%CI: 1.12-10.94, P = 0.03].

In terms of comparison with non-exenterative procedures, the latter were associated with fewer blood transfusions (P = 0.035) and more anastomoses (P < 0.001). However, resections with involved margins were less common after PE.

PE is an extensive procedure with a significant rate of perioperative adverse events. However, our analysis of patients with LAPRC treated with this procedure over 10 years confirmed that the survival benefits justify an aggressive attitude, provided that oncologic clearance is achievable. These procedures must be performed in a dedicated unit, and patients be managed under the care of multidisciplinary teams.

An aggressive attitude could confer a significant survival gain in carefully selected patients with LAPRC. The use of national and International registries is of great value to monitor the performance of centres dealing with PE and internal auditing; therefore, their use should be encouraged.

The authors would like to thank Hector Ortiz for coordinating the Rectal Cancer Project (Viking) and this manuscript. We thank all the collaborators in Rectal Cancer (Viking) Project.

Raúl Adell Carceller (Hospital de Vinaroz), Juan Guillermo Ais Conde (Hospital de Segovia), Evelio Alonso Alonso (Complejo Asistencial de Burgos), Antonio Amaya Cortijo (Hospital San Juan de Dios del Aljarafe de Sevilla), Antonio Arroyo Sebastian (Hospital General Universitario de Elche), Pedro Barra Baños (Hospital General Reina Sofía de Murcia), Ricard Batlle Solé (Hospital de Santa María de Lleida), Juan C Bernal Sprekelsen (Hospital de Requena), Sebastiano Biondo (Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge), Francisco J Blanco Gonzalez (Hospital La Ribera, Alzira), Santiago Blanco (Hospital de Reus), J Bollo (Hospital Universitari de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau de Barcelona), Nieves Cáceres Alvarado (Complejo Hospitalario de Vigo Xeral + Meixoeiro), Ignasi Camps Ausas (Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol de Badalona), Ramon Cantero Cid (Hospital Infanta Sofía de Madrid), José Antonio Carmona Saez (Hospital Nuestra Señora de Sonsoles de Ávila), Enrique Casal Nuñez (Complejo Hospitalario de Vigo Xeral + Meixoeiro), Luis Cristobal Capitán Morales (Hospital Virgen Macarena de Sevilla), Guillermo Carreño Villarreal (Hospital de Cabueñes de Gijón), Jesús Cifuentes Tebar (Hospital General de Albacete), Miguel Á Ciga Lozano (Hospital Virgen del Camino-Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra), Antonio Codina Cazador (Hospital Universitari de Girona Dr. Josep Trueta), Juan de Dios Franco Osorio (Hospital General de Jerez), María de la Vega Olías (Hospital Puerto Real de Cádiz), Mario de Miguel Velasco (Hospital Virgen del Camino-Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra), Sergio Rodrigo del Valle (Hospital General Rafael Mendez de Murcia), José G Díaz Mejías (Hospital Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria de Tenerife), José M Díaz Pavón (Hospital Virgen del Rocío de Sevilla), Javier Die Trill (Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal de Madrid), José L Dominguez Tristancho (Hospital de Mérida), Paula Dujovne Lindenbaum (Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón), José Errasti Alustiza (Hospital Txagorritxu de Vitoria), Alejandro Espí Macias (Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia), Eloy Espín Basany (Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron de Barcelona), Rafael Estévan Estévan (Instituto Valenciano de Oncología IVO), Alfredo M Estevez Diz (Hospital Policlínico Povisa de Vigo), Luis Flores (Hospital Clínico y Provincial de Barcelona), Domenico Fraccalvieri (Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge), Alessandro Garcea (Hospital Torrevieja Salud UTE), Mauricio García Alonso (Hospital Clínico San Carlos de Madrid), Miguel Garcia Botella (Hospital General Universitario de Valencia), Maria José García Coret (Hospital General Universitario de Valencia), Alfonso García Fadrique (Instituto Valenciano de Oncología IVO), José M García García (Hospital de Cruces), Jacinto García García (Complejo Asistencial de Salamanca), Eduardo García-Granero (Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe de Valencia), Jesús Á Garijo Alvarez (Hospital de Torrejón), José Gomez Barbadillo (Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía de Córdoba), Fernando Gris (Hospital Universitari Joan XXIII de Tarragona), Verónica Gumbau (Hospital General Universitario de Valencia), Javier Gutierrez (Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén), Pilar Hernandez Casanovas (Hospital Universitari de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau de Barcelona), Daniel Huerga Alvarez (Hospital Universitario de Fuenlabrada), Ana M Huidobro Piriz (Complejo Hospitalario de Palencia), Francisco Javier Jimenez Miramón (Hospital Universitario de Getafe), Ana Lage Laredo (Hospital Nuestra Señora del Rosell), Alberto Lamiquiz Vallejo (Hospital de Cruces), Félix Lluis Casajuana (Hospital General Universitario de Alicante), Manuel López Lara (Hospital Espíritu Santo de Santa Coloma de Gramanet), Juan A Lujan Mompean (Hospital Virgen de la Arrixaca), María Victoria Maestre (Hospital Virgen del Rocío de Sevilla), Eva Martí Martínez (Hospital Dr. Peset de Valencia), M Martinez (Hospital Universitari de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau de Barcelona), Javier Martinez Alegre (Hospital Infanta Sofía de Madrid), Gabriel Martínez Gallego (Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén), Roberto Martinez Pardavila (Onkologika de San Sebastian), Olga Maseda Díaz (Hospital Xeral de Lugo), Mónica Millan Schediling (Hospital Universitari Joan XXIII de Tarragona), Benito Mirón (Hospital Clínico Universitario San Cecilio de Granada), José Monzón Abad (Hospital Miguel Servet de Zaragoza), José A Múgica Martinera (Hospital Donostia), Francisco Olivet Pujol (Hospital Universitari de Girona Dr. Josep Trueta), Mónica Orelogio Orozco (Hospital General Juan Ramón Jimenez de Huelva), Luis Ortiz de Zarate (Consorci Sanitari Integral - Hospital General de L’Hospitalet y Hospital Moisés Broggi), Rosana Palasí Gimenez (Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe de Valencia), Natividad Palencia García (Hospital de Henares, Coslada), Pablo Palma Carazo (Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves), Alberto Parajo Calvo (Complejo Hospitalario de Ourense), Jesús Paredes Cotore (Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago de Compostela), Carlos Pastor Idoate (Fundación Jimenez Díaz), Miguel Pera Roman (Hospital del Mar de Barcelona), Francisco Pérez Benítez (Hospital Clínico Universitario San Cecilio de Granada), José A Pérez García (Hospital Virgen del Puerto de Plasencia), Marta Piñol Pascual (Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol de Badalona), Isabel Prieto Nieto (Hospital Universitario La Paz de Madrid), Ricardo Rada Morgades (Hospital General Juan Ramón Jimenez de Huelva), Mónica Reig Pérez (Hospital San Juan de Dios del Aljarafe de Sevilla), Ángel Reina Duarte (Hospital Torrecárdenas de Almería), Didac Ribé Serrat (Hospital General de Granollers), Xavier Rodamilans (Hospital de Santa María de Lleida), María D Ruiz Carmona (Hospital de Sagunto), Marcos Rodriguez Martin (Hospital Gregorio Marañón de Madrid), Francisco Romero Aceituno (Hospital San Pedro de Alcántara de Cáceres), Jesús Salas Martínez (Complejo Hospitalario de Badajoz), Ginés Sánchez de la Villa (Hospital General Rafael Mendez de Murcia), Inmaculada Segura Jimenez (Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves), José Enrique Sierra Grañon (Hospital Universitario Arnau de Vilanova de Lleida), Amparo Solana Bueno (Hospital de Manises), Albert Sueiras Gil (Hospital de Viladecans), Teresa Torres Sanchez (Hospital Dr. Peset de Valencia), Natalia Uribe Quintana (Hospital Arnau de Vilanova de Valencia), Javier Valdés Hernández (Hospital Virgen Macarena de Sevilla), Fancesc Vallribera (Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron de Barcelona), Vicent Viciano Pascual (Hospital Lluis Alcanyis de Xàtiva).

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Spain

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: El-Hussuna A, Jurado M S- Editor: Ma RY L- Editor: A E- Editor: Huang Y

| 1. | US Cancer Statistics Working Group. United States Cancer Statistics: 1999-2014 Incidence and Mortality Web-based Report. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute; 2017. Accessed March 2, 2018. Available from: https://nccd.cdc.gov/USCSDataViz/rdPage.aspx. |

| 2. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fedewa SA, Ahnen DJ, Meester RGS, Barzi A, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:177-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2526] [Cited by in RCA: 2912] [Article Influence: 364.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 3. | SEER Cancer Stat Facts: Colorectal Cancer. National Cancer Institute. Accessed March 2. 2018; Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/colorect.html. |

| 4. | MERCURY Study Group. Diagnostic accuracy of preoperative magnetic resonance imaging in predicting curative resection of rectal cancer: prospective observational study. BMJ. 2006;333:779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 666] [Cited by in RCA: 659] [Article Influence: 34.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kontovounisios C, Tan E, Pawa N, Brown G, Tait D, Cunningham D, Rasheed S, Tekkis P. The selection process can improve the outcome in locally advanced and recurrent colorectal cancer: activity and results of a dedicated multidisciplinary colorectal cancer centre. Colorectal Dis. 2017;19:331-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Brown KGM, Solomon MJ, Koh CE. Pelvic Exenteration Surgery: The Evolution of Radical Surgical Techniques for Advanced and Recurrent Pelvic Malignancy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60:745-754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Simillis C, Baird DL, Kontovounisios C, Pawa N, Brown G, Rasheed S, Tekkis PP. A Systematic Review to Assess Resection Margin Status After Abdominoperineal Excision and Pelvic Exenteration for Rectal Cancer. Ann Surg. 2017;265:291-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Selvaggi F, Fucini C, Pellino G, Sciaudone G, Maretto I, Mondi I, Bartolini N, Caminati F, Pucciarelli S. Outcome and prognostic factors of local recurrent rectal cancer: a pooled analysis of 150 patients. Tech Coloproctol. 2015;19:135-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Harji DP, Griffiths B, McArthur DR, Sagar PM. Surgery for recurrent rectal cancer: higher and wider? Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:139-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Koh CE, Solomon MJ, Brown KG, Austin K, Byrne CM, Lee P, Young JM. The Evolution of Pelvic Exenteration Practice at a Single Center: Lessons Learned from over 500 Cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60:627-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rottoli M, Vallicelli C, Boschi L, Poggioli G. Outcomes of pelvic exenteration for recurrent and primary locally advanced rectal cancer. Int J Surg. 2017;48:69-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Garcia-Granero A, Biondo S, Espin-Basany E, González-Castillo A, Valverde S, Trenti L, Gil-Moreno A, Kreisler E. Pelvic exenteration with rectal resection for different types of malignancies at two tertiary referral centres. Cir Esp. 2018;96:138-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | PelvEx Collaborative. Surgical and Survival Outcomes Following Pelvic Exenteration for Locally Advanced Primary Rectal Cancer: Results from an International Collaboration. Ann Surg. 2017; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 28.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | PelvEx Collaborative. Factors affecting outcomes following pelvic exenteration for locally recurrent rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2018;105:650-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ortiz H, Codina A. Rectal cancer project of the Spanish Association of Surgeons (Viking project): Past and future. Cir Esp. 2016;94:63-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ. 2007;335:806-808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3438] [Cited by in RCA: 6246] [Article Influence: 347.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wibe A, Møller B, Norstein J, Carlsen E, Wiig JN, Heald RJ, Langmark F, Myrvold HE, Søreide O; Norwegian Rectal Cancer Group. A national strategic change in treatment policy for rectal cancer--implementation of total mesorectal excision as routine treatment in Norway. A national audit. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:857-866. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Biondo S, Ortiz H, Lujan J, Codina-Cazador A, Espin E, Garcia-Granero E, Kreisler E, de Miguel M, Alos R, Echeverria A. Quality of mesorectum after laparoscopic resection for rectal cancer - results of an audited teaching programme in Spain. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12:24-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Beyond TME Collaborative. Consensus statement on the multidisciplinary management of patients with recurrent and primary rectal cancer beyond total mesorectal excision planes. Br J Surg. 2013;100:1009-1014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ortiz H, Ciga MA, Armendariz P, Kreisler E, Codina-Cazador A, Gomez-Barbadillo J, Garcia-Granero E, Roig JV, Biondo S; Spanish Rectal Cancer Project. Multicentre propensity score-matched analysis of conventional versus extended abdominoperineal excision for low rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2014;101:874-882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | García-Granero E, Faiz O, Muñoz E, Flor B, Navarro S, Faus C, García-Botello SA, Lledó S, Cervantes A. Macroscopic assessment of mesorectal excision in rectal cancer: a useful tool for improving quality control in a multidisciplinary team. Cancer. 2009;115:3400-3411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Quirke P, Steele R, Monson J, Grieve R, Khanna S, Couture J, O’Callaghan C, Myint AS, Bessell E, Thompson LC. Effect of the plane of surgery achieved on local recurrence in patients with operable rectal cancer: a prospective study using data from the MRC CR07 and NCIC-CTG CO16 randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2009;373:821-828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 833] [Cited by in RCA: 752] [Article Influence: 47.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Nagtegaal ID, van de Velde CJ, van der Worp E, Kapiteijn E, Quirke P, van Krieken JH; Cooperative Clinical Investigators of the Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group. Macroscopic evaluation of rectal cancer resection specimen: clinical significance of the pathologist in quality control. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1729-1734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 660] [Cited by in RCA: 680] [Article Influence: 29.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Brunschwig A. Complete excision of pelvic viscera for advanced carcinoma; a one-stage abdominoperineal operation with end colostomy and bilateral ureteral implantation into the colon above the colostomy. Cancer. 1948;1:177-183. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Heriot AG, Byrne CM, Lee P, Dobbs B, Tilney H, Solomon MJ, Mackay J, Frizelle F. Extended radical resection: the choice for locally recurrent rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:284-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Bhangu A, Ali SM, Darzi A, Brown G, Tekkis P. Meta-analysis of survival based on resection margin status following surgery for recurrent rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:1457-1466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Nielsen MB, Rasmussen PC, Lindegaard JC, Laurberg S. A 10-year experience of total pelvic exenteration for primary advanced and locally recurrent rectal cancer based on a prospective database. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:1076-1083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Loughrey MB McManus DT. Pelvic Exenteration Specimens. Histopathology Specimens. London: Springer 2013; . [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 29. | Yang TX, Morris DL, Chua TC. Pelvic exenteration for rectal cancer: a systematic review. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:519-531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Coleman MP, Forman D, Bryant H, Butler J, Rachet B, Maringe C, Nur U, Tracey E, Coory M, Hatcher J. Cancer survival in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and the UK, 1995-2007 (the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership): an analysis of population-based cancer registry data. Lancet. 2011;377:127-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 880] [Cited by in RCA: 893] [Article Influence: 63.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Hsu TW, Chiang FF, Chen MC, Wang HM. Pelvic exenteration for men with locally advanced rectal cancer: a morbidity analysis of complicated cases. Asian J Surg. 2011;34:115-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | García-Granero E, Navarro F, Cerdán Santacruz C, Frasson M, García-Granero A, Marinello F, Flor-Lorente B, Espí A. Individual surgeon is an independent risk factor for leak after double-stapled colorectal anastomosis: An institutional analysis of 800 patients. Surgery. 2017;162:1006-1016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Georgiou PA, Bhangu A, Brown G, Rasheed S, Nicholls RJ, Tekkis PP. Learning curve for the management of recurrent and locally advanced primary rectal cancer: a single team’s experience. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17:57-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Baguena G, Pellino G, Frasson M, Roselló S, Cervantes A, García-Granero A, Giner F, García-Granero E. Prognostic impact of pT stage and peritoneal invasion in locally advanced colon cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;In press. |

| 35. | Dayal S, Moran B. LOREC: the English Low Rectal Cancer National Development Programme. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2013;74:377-380. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Sahnan K, Pellino G, Adegbola SO, Tozer PJ, Chandrasinghe P, Miskovic D, Hompes R, Warusavitarne J, Lung PFC. Development of a model of three-dimensional imaging for the preoperative planning of TaTME. Tech Coloproctol. 2018;22:59-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |