Published online Nov 28, 2018. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i44.5025

Peer-review started: August 30, 2018

First decision: October 14, 2018

Revised: October 15, 2018

Accepted: November 13, 2018

Article in press: November 13, 2018

Published online: November 28, 2018

Processing time: 90 Days and 2 Hours

To examine the association between the timing of endoscopy and the short-term outcomes of acute variceal bleeding in cirrhotic patients.

This retrospective study included 274 consecutive patients admitted with acute esophageal variceal bleeding of two tertiary hospitals in Korea. We adjusted confounding factors using the Cox proportional hazards model and the inverse probability weighting (IPW) method. The primary outcome was the mortality of patients within 6 wk.

A total of 173 patients received urgent endoscopy (i.e., ≤ 12 h after admission), and 101 patients received non-urgent endoscopy (> 12 h after admission). The 6-wk mortality rate was 22.5% in the urgent endoscopy group and 29.7% in the non-urgent endoscopy group, and there was no significant difference between the two groups before (P = 0.266) and after IPW (P = 0.639). The length of hospital stay was statistically different between the urgent group and non-urgent group (P = 0.033); however, there was no significant difference in the in-hospital mortality rate between the two groups (8.1% vs 7.9%, P = 0.960). In multivariate analyses, timing of endoscopy was not associated with 6-wk mortality (hazard ratio, 1.297; 95% confidence interval, 0.806-2.089; P = 0.284).

In cirrhotic patients with acute variceal bleeding, the timing of endoscopy may be independent of short-term mortality.

Core tip: Most guidelines recommend performing endoscopy for acute variceal bleeding within 12 h. However, the evidence level for this recommendation is very low. We found that, after inverse probability weighting matching, compared to non-urgent endoscopy, performing endoscopy within 12 h of admission (so-called urgent endoscopy) was not associated with short-term prognosis, including overall survival at 6 wk or transplant-free survival at 6 wk. Rather, age, hepatocellular carcinoma, model for end-stage liver disease score, and degree of ascites were related to short-term mortality. These results indicate that, in cirrhotic patients with acute variceal bleeding, the timing of endoscopy does not appear to be associated with short-term prognosis.

- Citation: Yoo JJ, Chang Y, Cho EJ, Moon JE, Kim SG, Kim YS, Lee YB, Lee JH, Yu SJ, Kim YJ, Yoon JH. Timing of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy does not influence short-term outcomes in patients with acute variceal bleeding. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(44): 5025-5033

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v24/i44/5025.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i44.5025

Variceal bleeding is a common complication of cirrhosis of the liver, and in patients with cirrhosis, is found to be the cause of 60%-65% of bleeding episodes[1]. It increases the risk of mortality by approximately 15%-20%. Many guidelines recommend a standardized treatment of acute variceal bleeding[2-5]. Endoscopic procedures and endoscopic hemostasis techniques, e.g., band ligation, are considered very important in the treatment of such patients[6], with most guidelines recommending that emergency endoscopy be performed within 12 h of hospital arrival[4-6].

However, this recommendation appears to be based on “expert opinion”, rather than on the level of evidence, which is in fact very low. For example, one survey showed significant variability in gastoenterologists’ opinion of the timing of emergency endoscopy following variceal bleeding[7]. Moreover, there is little related research to date to support this current recommendation of endoscopy within 12 h of hospital arrival[8,9]. However, providing better evidence by clinically performing a randomized controlled trial on these acutely ill patients is problematic, because of their unstable vital signs and the ethical problems that would arise from this type of study.

Compared to other medical treatments such as vasoactive agents, endoscopy is a relatively invasive procedure and both the risk and benefit to the patient need to be considered. If unnecessary endoscopies are frequently performed, medical staff fatigue may increase dramatically, and so may the medical costs[10]. Moreover, if endoscopy is performed too early, the examination may be may not be adequate; for example it may be marred by remnant blood clots etc. As well, the risk of a procedure-related complication tends to increase when endoscopy is performed too early in patients with unstable condition compared to when performed in a more stable state[10,11]. To date, a gold standard recommended timing of endoscopy in patients with acute variceal bleeding has not been clearly determined.

The aim of this study was to examine the association between the timing of endoscopy and clinical outcomes in acute esophageal variceal bleeding.

We collected the data of cirrhotic patients undergoing routine clinical care in either of two tertiary hospitals (Seoul National University Hospital and Soon Chun Hyang University Bucheon Hospital) between January 2011 and December 2015. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Cirrhotic patients admitted via the emergency room (ER) with upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB), and diagnosed through endoscopy with acute variceal bleeding; and (2) aged over 19 years. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients who did not undergo endoscopic examination during ER stay (n = 38); (2) UGIB from other than variceal bleeding (e.g., peptic ulcer bleeding, portal hypertensive gastropathy bleeding) (n = 165); or (3) if endoscopy had been performed within 7 d prior to admission (n = 7). In total, 484 patients met the inclusion criteria and 210 patients were excluded as above. Finally, 274 patients were analyzed.

When a cirrhotic patient with UGIB arrived at the ER of each hospital, adequate fluid resuscitation, a prophylactic antibiotic, and a vasoactive drug with terlipressin were immediately administered at the time of admission. If peptic ulcer bleeding could not be ruled out, a proton pump inhibitor was also administrated. An emergency medical specialist first examined the patient, and consulted a gastrointestinal (GI) specialist about whether an endoscopy was to be performed. Then, the GI specialist determined the timing of the endoscopy, considering each patient’s age, presence of comorbidities such as renal failure or cardiopulmonary disease, presence of hepatic encephalopathy, hemodynamic instability, and laboratory abnormalities including anemia, lactic acidosis and coagulopathy. If patients did not exhibit poor clinical factors or they had signs of hepatic encephalopathy more than grade III, delayed endoscopic examination was considered. (In both hospitals, a GI specialist with technical expertise in the use of endoscopic devices is on call 24 h a day, 7 d a week.) Therapeutic endoscopy was performed using standard video-endoscopes (GIF-Q260 or GIF-Q290; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). When EVL failed, salvage treatments including endoscopic variceal obturation (EVO) using n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (NBC), insertion of a Sengstaken-Blakemore (SB) tube, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt, variceal embolization, or a combination of multiple treatment modalities were performed. When EVO was performed, NBC (Histoacryl®; B. Braun Dexon, Spangenberg, Germany) was mixed with ethiodized oil (Lipiodol; Guerbert, Roissy, France) and was injected as a bolus dose of 0.5-2 mL, depending on the amount of bleeding.

Two independent reviewers (Yoo JJ and Chang Y), each with more than 5 years of endoscopic experience, screened medical records and endoscopic reports to confirm that each case was of a true acute gastroesophageal variceal bleeding. If a patient was admitted more than once during the study period due to variceal bleeding, the earliest visit was selected for inclusion in the analysis. Demographics, relevant medical history, any comorbid conditions, and relevant laboratory findings at the time of admission were collected. Two widely-studied UGIB prognostic scores of each of the patients, namely the Glasgow-Blatchford score (GBS) and the Rockall score, were also calculated[12,13]. If the patient had died during the study period, the cause of death was evaluated from hospital records, where possible.

Time to endoscopy was defined as the time interval from the hospital arrival to the initial endoscopic examination[14]. Urgent endoscopy was defined according to the guidelines as an endoscopic examination performed within 12 h of admission, and non-urgent endoscopy defined as one performed after 12 h[5].

The primary outcome for this study was the 6-wk mortality rate following variceal bleeding. The secondary outcomes were: 6-wk mortality or transplantation rates, hospital admission duration, in-hospital mortality, and re-bleeding rate.

Only the patients with complete data were analyzed in this study. Frequencies with percentages and means with standard deviations were used for descriptive statistics. Statistical differences between the groups were investigated using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the Student’s t test or Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables. Cumulative 6-wk survival and transplant-free survival (TFS) rates after acute variceal bleeding were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences between the curves were compared using the log-rank test. In patients with loss to follow-up, the data were censored on the last date on which their survival status was known. The effect of endoscopic timing on clinical outcomes was assessed using the Cox proportional hazards regression model. If multicollinearity occurred between the individual components in the univariate analysis, only the most relevant prognostic parameter was included in the final multivariable model. The inverse probability weighting method based on propensity score was applied so as to correct baseline differences between the two groups (urgent endoscopy vs non-urgent endoscopy). A P-value less than 0.05 was considered significant. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were also calculated. All statistical analyses were performed using R (version 3.3.3, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), or PASW version 18.0 statistical software (SPSS Inc.; Chicago, IL, United States).

The baseline characteristics of the patients enrolled in the study are reported in Table 1. The mean age of the patients was 58.05 ± 12.10 years, and 75.5% (207) were male. The proportion of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) was 54.4% (149). Sixty-five percent of the patients had experienced variceal bleeding prior to the study period. Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection was the most common etiology of cirrhosis, followed by alcohol use and other causes. Sixty percent of patients presented with any grade of ascites.

| Characteristics | Unweighted | Inverse probability weighting | ||||||

| All patients(n = 274) | Urgent endoscopy(n = 173) | Non-urgent endoscopy(n = 101) | P value | All patients(n = 272) | Urgent endoscopy(n = 172) | Non-urgent endoscopy(n = 100) | P value | |

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Age (yr) | 58.05 ± 12.10 | 57.62 ± 12.09 | 58.77 ± 12.22 | 0.45 | 58.14 ± 0.85 | 58.17 ± 1.03 | 58.10 ± 1.34 | 0.971 |

| Sex (male) | 207 (75.5) | 128 (74.0) | 79 (78.2) | 0.469 | 205 (74.6) | 127 (37.2) | 78 (37.4) | 0.956 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 149 (54.4) | 97 (56.1) | 52 (51.5) | 0.452 | 148 (54.8) | 97 (27.8) | 51 (27.0) | 0.830 |

| Prior variceal upper GI bleeding | 179 (65.3) | 110 (63.6) | 69 (68.3) | 0.511 | 178 (65.7) | 109 (32.3) | 69 (33.5) | 0.713 |

| Prior non-variceal upper GI bleeding | 8 (2.9) | 2 (1.2) | 6 (5.9) | 0.055 | 8 (2.9) | 2 (1.4) | 6 (1.5) | 0.890 |

| Initial hepatic encephalopathy | < 0.001 | 0.939 | ||||||

| None | 241 (88.0) | 164 (94.8) | 77 (76.2) | 239 (88.6) | 163 (44.5) | 76 (44.4) | ||

| Grade I-II | 16 (5.8) | 5 (2.9) | 11 (10.9) | 16 (5.4) | 5 (2.5) | 11 (2.9) | ||

| Grade III-IV | 17 (6.2) | 4 (2.3) | 13 (12.9) | 17 (5.7) | 4 (2.6) | 13 (3.1) | ||

| Initial ascites | 0.067 | 0.994 | ||||||

| None | 111 (40.5) | 77 (44.5) | 34 (33.7) | 111 (41.1) | 77 (20.3) | 34 (20.8) | ||

| Mild | 77 (28.1) | 50 (28.9) | 27 (26.7) | 76 (29.4) | 49 (14.7) | 27 (14.7) | ||

| Moderate to severe | 86 (31.4) | 46 (26.6) | 40 (39.6) | 85 (29.5) | 46 (14.6) | 39 (14.9) | ||

| Etiology | 0.985 | 0.930 | ||||||

| HBV | 137 (50.0) | 86 (49.8) | 51 (50.5) | 136 (49.7) | 86 (24.4) | 50 (25.33) | ||

| HCV | 25 (9.1) | 16 (9.2) | 9 (8.9) | 25 (9.4) | 16 (5.4) | 9 (4.0) | ||

| Alcohol | 69 (25.2) | 43 (24.9) | 26 (25.7) | 68 (24.0) | 42 (12.3) | 26 (12.7) | ||

| Others | 43 (15.7) | 28 (16.2) | 15 (14.9) | 43 (16.0) | 28 (8.0) | 15 (8.0) | ||

| Vital signs | ||||||||

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 117 ± 26 | 116 ± 26 | 120 ± 26 | 0.221 | 118 ± 2 | 116 ± 2 | 119 ± 3 | 0.408 |

| Heart rate (beat/min) | 95 ± 18 | 96 ± 19 | 94 ± 17 | 0.551 | 95 ± 1 | 95 ± 1 | 95 ± 2 | 0.827 |

| Laboratory values | ||||||||

| Hemoglobin | 9.2 ± 2.5 | 9.0 ± 2.5 | 9.6 ± 2.5 | 0.044 | 9.1 ± 0.2 | 8.8 ± 0.2 | 9.3 ± 0.3 | 0.105 |

| Platelet count (103/mL) | 117 + 79 | 118 ± 78 | 114 ± 80 | 0.701 | 118 ± 5 | 119 ± 6 | 118 ± 8 | 0.917 |

| Total bilirubin | 3.8 ± 5.8 | 3.5 ± 5.3 | 4.5 ± 6.5 | 0.148 | 3.7 ± 0.4 | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 0.817 |

| Serum albumin | 2.9 ± 0.6 | 2.9 ± 0.6 | 2.9 ± 0.7 | 0.702 | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 4.0 ± 0.1 | 0.736 |

| Prothromin time (INR) | 1.6 ± 1.8 | 1.4 ± 0.6 | 1.8 ± 2.9 | 0.046 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 0.157 |

| Serum creatinine | 1.3 ± 1.5 | 1.4 ± 1.8 | 1.2 ± 1.0 | 0.24 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 0.07 |

| MELD score | 15.9 ± 7.8 | 15.4 ± 6.9 | 16.9 ± 9.2 | 0.112 | 15.6 ± 0.5 | 15.6 ± 0.5 | 15.6 ± 0.8 | 0.964 |

| Prognostic scores | ||||||||

| Glasgow-Blatchford score | 9.1 ± 3.5 | 9.2 ± 3.3 | 9.1 ± 3.9 | 0.818 | 9.3 ± 0.2 | 9.3 ± 0.3 | 9.3 ± 0.4 | 0.907 |

| Rockall score | 3.9 ± 1.4 | 4.0 ± 1.4 | 3.6 ± 1.5 | 0.021 | 3.4 ± 0.1 | 3.9 ± 0.1 | 3.9 ± 0.2 | 0.875 |

| Endoscopy | ||||||||

| Time to endoscopy, hours, median (IQR) | 12.7 (2.8-16.5) | 4.0 (2.1-6.8) | 19.5 (15.0-35.5) | < 0.001 | 12.5 (2.8-16.4) | 4.0 (2.2-6.8) | 19.5 (15.1-35.4) | < 0.001 |

At the time of hospital arrival, the heart rate of the patients was found to be abnormally high, with an average of 95 beat per minute, and their mean systolic pressure was 116 ± 26 mmHg. They showed deteriorated liver function with a mean model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score of 15.9 ± 7.8 points. The mean Glasgow-Blatchford score was 9.1 ± 3.5 points, suggesting a poor prognosis.

Patients underwent endoscopic examination at an average of 9.1 ± 3.5 h after arrival at the hospital. Based on the timing of the endoscopy, patients were divided into an urgent endoscopy group (< 12 h) and a non-urgent endoscopy group (≥ 12 h). The baseline characteristics of the two groups were similar and there was no significant difference in the MELD scores (15.4 ± 6.9 vs 16.9 ± 9.2; P = 0.088) between the two groups.

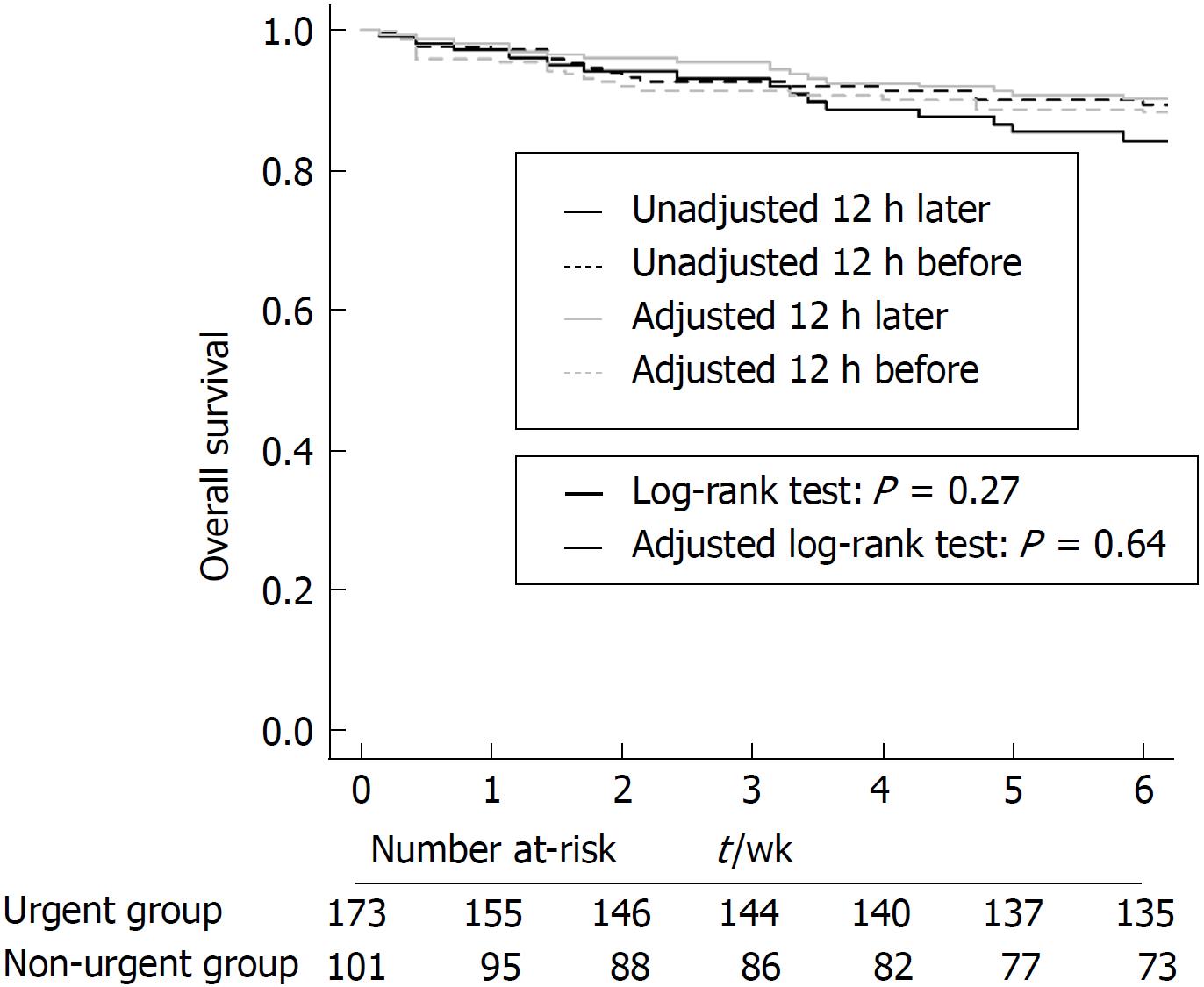

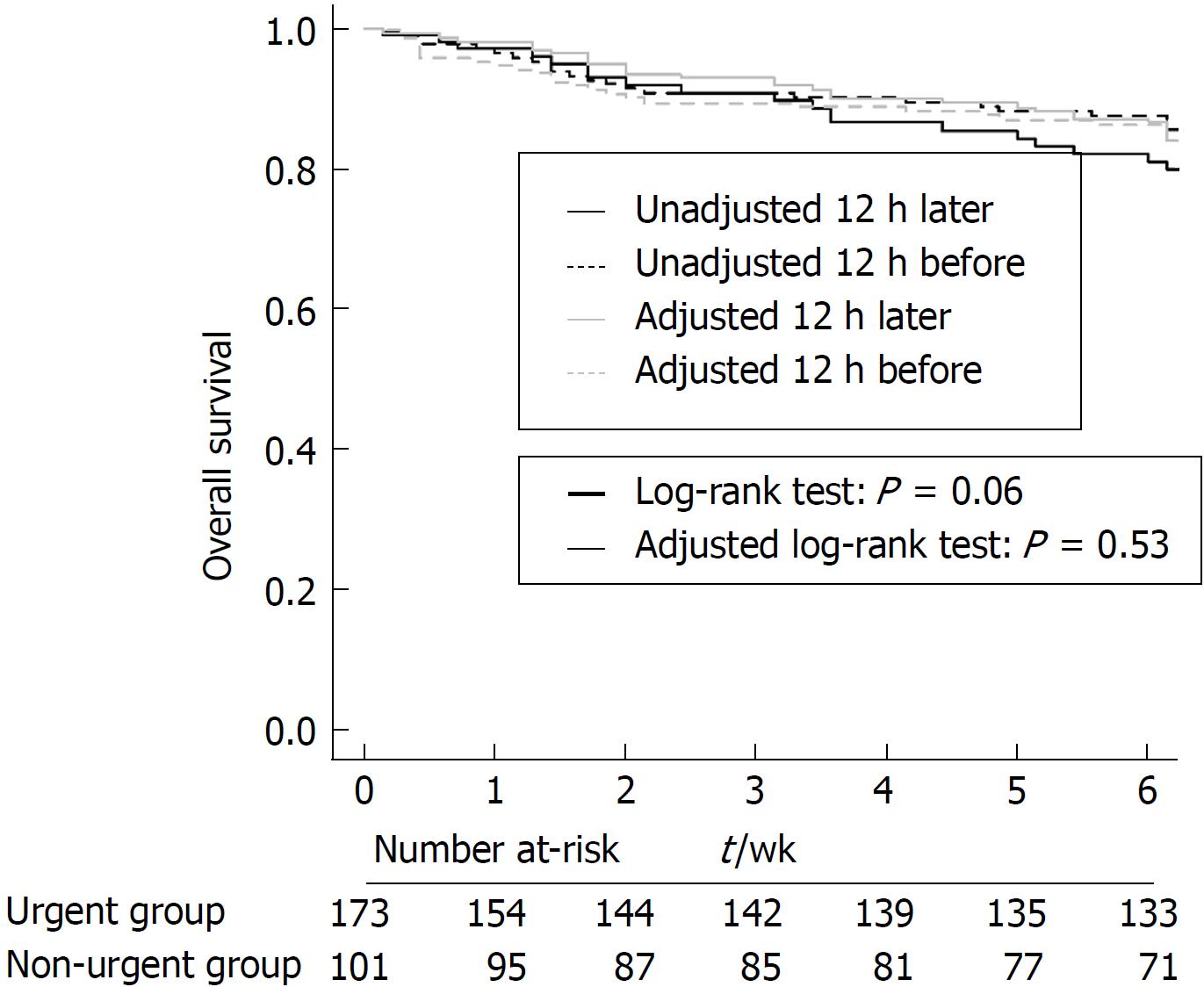

The 6-wk mortality rate was 22.5% in the urgent endoscopy group and 29.7% in the non-urgent endoscopy group, and there were no significant differences between the two groups (P = 0.266, Figure 1). After IPW, the baseline characteristics were well balanced between the two groups (Tables 1). The IPW-adjusted analysis also showed that both groups did not differ in terms of the risk of death (P = 0.639). The 6-wk mortality or transplantation rate was slightly lower in the urgent group but with marginal significance (P = 0.060, Figure 2). However, after IPW there was no significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.532).

Other clinical outcomes are described in Table 2. Although the median hospital admission duration was similar in both groups, significant differences observed in the mean rank scores (i.e., Mann-Whitney U test), suggesting that the data for the non-urgent group were more right skewed (P = 0.033)[15]. However, there was no significant difference in the in-hospital mortality rate between the urgent group and the non-urgent group (8.1% vs 7.9%; P = 0.960).

| Outcomes | All patients(n = 274) | Urgent endoscopy(n = 173) | Non-urgent endoscopy(n = 101) | P value |

| Hospital admission duration, days, median (IQR) | 4.0 (3.0-9.5) | 4.0 (2.0-9.0) | 4.0 (3.0-11.0) | 0.033 |

| In-hospital mortality | 22 (8.0) | 14 (8.1) | 8 (7.9) | 0.960 |

| Re-bleeding rate | 60 (21.9) | 35 (20.2) | 25 (24.8) | 0.449 |

| Six-week mortality | 69 (25.2) | 39 (22.5) | 30 (29.7) | 0.197 |

| Liver transplantation | 25 (9.1) | 14 (8.1) | 11 (10.9) | 0.515 |

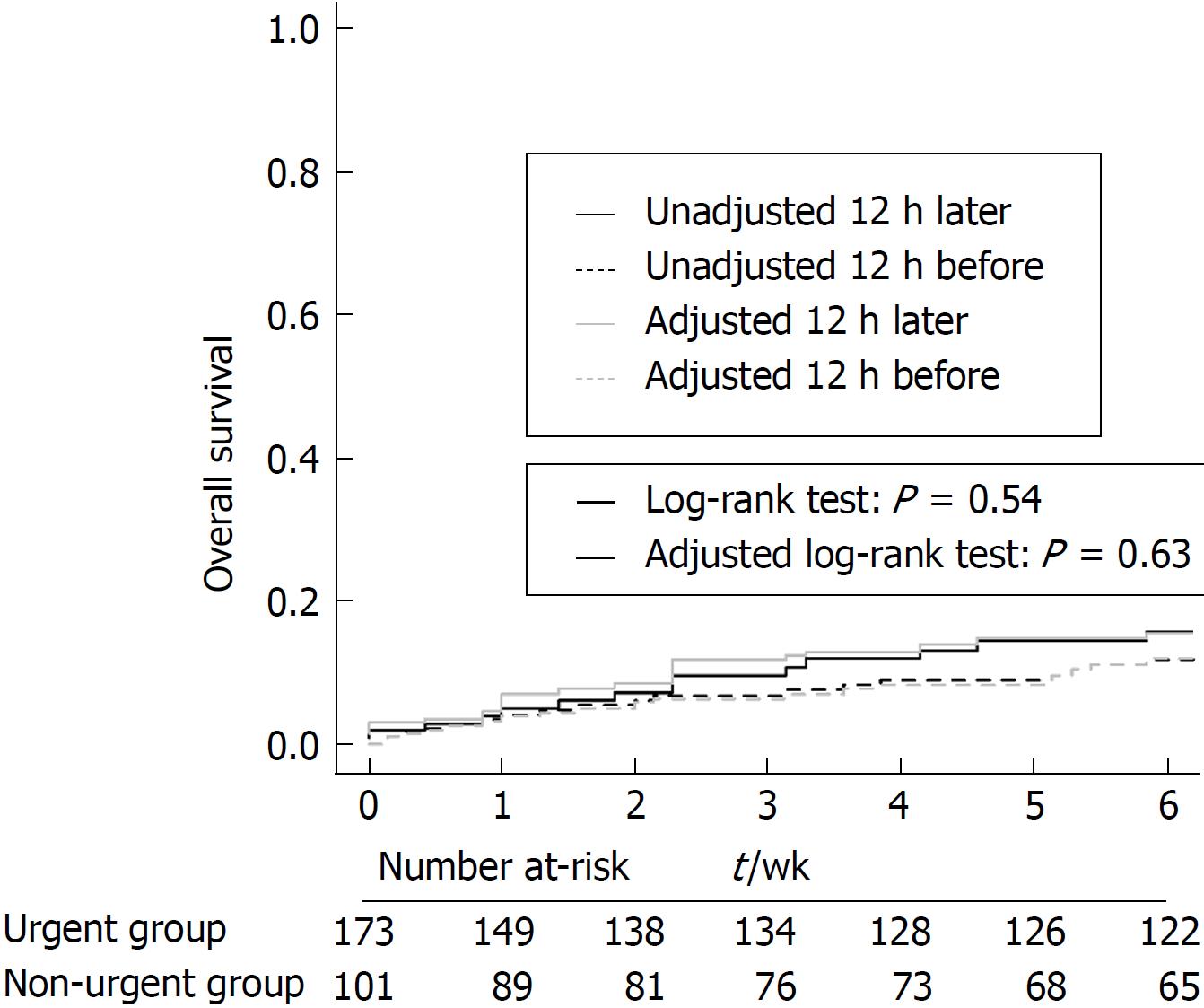

The rate of variceal re-bleeding within 6 wk was 10.4% in the urgent group and 12.9% in the non-urgent group, which was statistically nonsignificant (P = 0.557). The Kaplan-Meier analysis of time to re-bleeding also showed no significant difference between the two groups either before or after IPW matching (P = 0.538 and 0.631, respectively; Figure 3).

Finally, we analyzed clinical predictors associated with 6-wk mortality (Table 3). Compared with non-urgent endoscopy, urgent endoscopy was not independently associated with short-term mortality [adjusted hazard ratio (aHR): 1.297; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.806-2.089; P = 0.284). On the other hand, the following were independent risk factors of 6-wk mortality: advanced age (aHR: 1.035; 95%CI: 1.011-1.0059; P = 0.004), high MELD score (aHR: 1.049; 95%CI: 1.024-1.074; P < 0.001), and the presence of ascites. In particular, the grade of ascites showed dose-dependency. When the ascites was present to a more than moderate degree, the 6-wk mortality was increased 3.346-fold compared to when there was no ascites. Also, the presence of HCC (aHR: 1.929; 95%CI: 1.072-3.469; P = 0.028) increased the risk of short-term mortality in variceal bleeding patients. However, the GBS and Rockall scores were not significantly associated with 6-wk mortality in patients with acute variceal bleeding. Similar results were obtained when the factors predicting transplantation or death were analyzed (Supplementary Table 1).

| Variable | Univariable | Multivariable | ||

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age | 1.037 (1.016-1.059) | < 0.001 | 1.035 (1.011-1.059) | 0.004 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 1 | |||

| Male | 0.946 (0.543-1.664) | 0.845 | ||

| Etiology | ||||

| Non-viral | 1 | 1 | ||

| Viral | 0.536 (0.319-0.902) | 0.019 | 0.683 (0.384-1.214) | 0.194 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 2.442 (1.439-4.142) | 0.001 | 1.929 (1.072-3.469) | 0.028 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 0.535 (0.292-0.978) | 0.042 | 0.423 (0.225-0.795) | 0.008 |

| Hypertension | 0.994 (0.521-1.894) | 0.984 | ||

| Prior variceal upper GI bleeding | 0.916 (0.561-1.497) | 0.726 | ||

| Prior non-variceal upper GI bleeding | 3.92E-8 (0-INF) | 0.996 | ||

| Systolic blood pressure | 1.003 (0.994-1.012) | 0.489 | ||

| Heart rate | 1.005 (0.992-1.018) | 0.477 | ||

| MELD score1 | 1.062 (1.041-1.083) | < 0.001 | 1.049(1.024-1.074) | < 0.001 |

| ALT | 1.001 (0.999-1.002) | 0.123 | ||

| Serum creatinine1 | 1.075 (1.013-1.197) | 0.018 | ||

| Serum total bilirubin1 | 1.047 (1.012-1.083) | 0.007 | ||

| Prothrombin time1 | 1.128 (1.043-1.221) | 0.003 | ||

| Initial hepatic encephalopathy | ||||

| None | 1 | 1 | ||

| Grade I-II | 1.393 (0.558-3.477) | 0.477 | 0.555 (0.200-1.537) | 0.257 |

| Grade III-IV | 2.229 (1.062-4.677) | 0.034 | 0.969 (0.449-2.088) | 0.935 |

| Initial ascites | ||||

| None | 1 | 1 | ||

| Mild | 2.064 (1.003-4.250) | 0.049 | 1.604 (0.766-3.361) | 0.210 |

| Moderate to severe | 4.675 (2.494-8.766) | < 0.001 | 3.346 (1.715-6.527) | < 0.001 |

| Glasgow-Blatchford score | 0.980 (0.917-1.047) | 0.550 | ||

| Rockall score | 1.138 (0.968-1.338) | 0.118 | ||

| Timing of endoscopy | ||||

| Non-urgent (≥ 12 h) | 1 | |||

| Urgent (< 12 h) | 1.297 (0.806-2.088) | 0.284 | ||

The decision as to when to perform endoscopy in patients with acute variceal bleeding has always been controversial. Guidelines have traditionally recommended that endoscopy be performed within 12 h of admission, but to date there has been little actual supporting evidence for this[4,5,16]. Our study analyzed relatively large numbers of patients, and concluded that, despite the existing guidelines, the timing of endoscopy was not associated with short-term survival or mortality in patients with variceal bleeding.

Studies on the optimal timing of endoscopy in patients with acute variceal bleeding have taken place mostly at a time in the past when sclerotherapy was the mainstream treatment. Several randomized control trials reported at this time have concluded that, if endoscopy was performed early, clinical indices did not improve significantly[17,18]. In studies, including some meta-analyses, endoscopic treatment was recommended only when pharmacotherapy fails[19]. However, band ligation therapy has completely replaced sclerotherapy nowadays[20,21]. Moreover, it is now widely acknowledged that combination therapy is superior to pharmaco- or endoscopic monotherapy for acute variceal bleeding[22,23]. Paradoxically, however, in the age of band ligation, there has been little research so far on the optimal timing of endoscopy.

To date, there have been two relatively large-scale studies on the optimal timing of the endoscopy of variceal bleeding patients in the “band ligation era”. In a study published in Taiwan, early endoscopy (i.e., < 15 h) reduced in-hospital mortality, but did not have a significant impact on mortality[9]. Another study published in Canada showed that time-to-endoscopy did not appear to be associated with mortality[8]. Both studies exhibited selection bias, in that only hemodynamically stable patients were included. The authors suggested that in-hospital mortality was increased due to delays in time-to-endoscopy, but the baseline MELD score was higher in those patients with higher in-hospital mortality (16.5 vs 11.2)[9]. In other words, it is difficult to tell whether these patients’ increased in-hospital mortality was due to underlying liver disease or because of the delayed time-to-endoscopy. Finally, both studies analyzed the door-to-endoscopy time as a continuous variable, and therefore showed results that were not significant.

In our study, to overcome these limitations, we conducted IPW for baseline correction and analyzed “door-to-scope” time as a 12-h categorical variable according to the existing guidelines. Considering the degree to which the various factors that influence the timing of endoscopy may impact the clinical outcomes, it was essential to conduct the IPW. In fact, clinicians tend to perform endoscopy more quickly if the patient shows unstable features, and in this situation, the effect of endoscopy on survival is likely to be underestimated.

So, when is the appropriate time to do endoscopy in variceal bleeding? Research to date shows it is more complicated than just “the sooner the better”. In the Taiwan study, the authors divided endoscopic timing into several stages, but they failed to prove “the sooner, the better” concept[9]. Although we have not described it in this study, we analyzed the results of a door-to-endoscopy time of 6 h, but we failed to demonstrate a benefit with more urgent endoscopy. It seems that timing of endoscopy and clinical outcomes, including mortality, shows a non-linear correlation. For example, in peptic ulcer bleeding patients, the correlation between the timing of endoscopy and clinical outcomes is U-shaped, and we consider it likely to be similar in variceal bleeding patients[24]. This phenomenon is believed to be due to the fact that basic resuscitation (e.g., adequate hydration, antibiotics) influences the patient’s outcome in the early stages of treatment[4,5,25]. If the patient is transported too early in order to undergo an endoscopic procedure, it may interfere with basic resuscitation during the critical early period of management, leading to a bad prognosis. Also, if the endoscopy is performed too soon, the quality of endoscopic examination may be suboptimal, due to poor preparation. In clinical practice, we sometimes find that delayed endoscopy, after using vasoactive drugs, is actually faster and safer.

In our study, the median door-to-endoscopy time in the non-urgent group was 19.5 h which was much longer than the recommended time. Although most guidelines recommend that endoscopy should be performed within 12 h of presentation, various clinical and facility factors may hamper guideline implementation in the real clinical settings[4,5,26,27]. To overcome these baseline imbalances, we used IPW method. After IPW, there were no significant differences in the short-term outcomes between two groups.

When it comes to studies of endoscopy, it is important to consider the selection of appropriate outcomes. Previous studies have focused primarily on long-term prognosis, such as overall survival or all-cause mortality. These studies have failed to show a reduction in mortality in urgent endoscopy. However, since the long-term prognosis of patients with variceal bleeding is mainly related to their basal liver function, it is unreasonable to associate a single-point endoscopy with a long-term prognosis. Indeed, in our data and in the Canadian studies, the most common cause of death was liver cirrhosis, not the bleeding itself (Supplementary Table 2). For this reason, unlike other studies, in our study we changed the endpoint to overall survival at 6 wk or TFS at 6 ws. We consider short-term outcomes to be more appropriate than long-term outcomes in demonstrating the precise effect of endoscopic timing on prognosis. In fact, the Barveno guideline recommends 6-wk mortality rather than OS as an outcome[5].

Consistent with previous reports, the length of hospital stay was statistically different between the urgent group and non-urgent group[10,28-30]. It may be due to more accurate diagnosis and earlier hemostasis of the bleeding source by urgent endoscopy, leading to decrease in the subsequent resource use including the length of stay and total hospitalization costs.

There are some limitations to our study. First, as with other studies, our study may be confounded by unmeasured factors because of its retrospective design. Clearly there are ethical difficulties in enrolling acute variceal bleeding patients into RCTs; nevertheless retrospective studies can be of benefit in providing reliable and practical information. Second, where there is no weekend rounder, the results of this study may be difficult to apply. Another issue to consider is that previous research refers to geographic variability in prognosis of UGIB patients.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that endoscopic timing may not affect the clinical outcomes of patients with esophageal variceal bleeding, especially in short-term outcomes. Therefore it is necessary to perform endoscopy at an appropriate time, depending on each patient’s condition. A prospective study, or a meta-analysis involving a greater number of centers in different countries, will assist in establishing a more accurate optimal timing for endoscopy.

The optimal timing of emergency endoscopy in acute variceal bleeding remains unclear. Most guidelines recommend performing endoscopy for acute variceal bleeding within 12 h of admission. However, the evidence level for this recommendation is very low, with few relevant studies to date to justify it

Determining the appropriate endoscopic timing is a very important issue, and both the risk and benefit to the patient need to be considered. We hypothesized that the earlier the endoscopy was performed, the better the short-term prognosis of the cirrhotic patients with variceal bleeding.

The aim of this study was to examine the association between the timing of endoscopy and the short-term prognosis of acute variceal bleeding in cirrhotic patients.

We performed a retrospective study of cirrhotic patients with variceal bleeding. Patients were divided into two groups according to the time of endoscopy. Urgent endoscopy group was defined as performing endoscopy before 12 h of admission and non-urgent endoscopy group after 12 h of admission. The inverse probability weighting (IPW) method based on propensity score was applied to correct baseline differences between the two groups, and compared short-term prognosis between the two groups.

In 274 patients, 173 patients received urgent endoscopy, and 101 patients received non-urgent endoscopy. After IPW method, short term prognosis including 6-wk mortality rate or 6-wk transplantation rate was not different between the two groups. In multivariate analyses, timing of endoscopy was not associated with 6-wk mortality. Other factors associated with 6-wk mortality were age, hepatocellular carcinoma, MELD score, and degree of ascites.

Timing of endoscopy may not affect the clinical short-term outcomes of patients with esophageal variceal bleeding.

Because this is a retrospective study, a prospective study to determine the appropriate timing of endoscopy considering risk and benefit is needed for the future.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Cholongitas E, Karatapanis S, Stanciu C S- Editor: Wang XJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Yin SY

| 1. | Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey WD; Practice Guidelines Committee of American Association for Study of Liver Diseases; Practice Parameters Committee of American College of Gastroenterology. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2086-2102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 257] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Villanueva C, Piqueras M, Aracil C, Gómez C, López-Balaguer JM, Gonzalez B, Gallego A, Torras X, Soriano G, Sáinz S. A randomized controlled trial comparing ligation and sclerotherapy as emergency endoscopic treatment added to somatostatin in acute variceal bleeding. J Hepatol. 2006;45:560-567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Abraldes JG, Villanueva C, Bañares R, Aracil C, Catalina MV, Garci A-Pagán JC, Bosch J; Spanish Cooperative Group for Portal Hypertension and Variceal Bleeding. Hepatic venous pressure gradient and prognosis in patients with acute variceal bleeding treated with pharmacologic and endoscopic therapy. J Hepatol. 2008;48:229-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 224] [Cited by in RCA: 223] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Garcia-Tsao G, Abraldes JG, Berzigotti A, Bosch J. Portal hypertensive bleeding in cirrhosis: Risk stratification, diagnosis, and management: 2016 practice guidance by the American Association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology. 2017;65:310-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1108] [Cited by in RCA: 1441] [Article Influence: 180.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 5. | de Franchis R, Baveno VI Faculty. Expanding consensus in portal hypertension: Report of the Baveno VI Consensus Workshop: Stratifying risk and individualizing care for portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2015;63:743-752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2011] [Cited by in RCA: 2293] [Article Influence: 229.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 6. | Seo YS. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2018;24:20-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cheung J, Wong W, Zandieh I, Leung Y, Lee SS, Ramji A, Yoshida EM. Acute management and secondary prophylaxis of esophageal variceal bleeding: a western Canadian survey. Can J Gastroenterol. 2006;20:531-534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cheung J, Soo I, Bastiampillai R, Zhu Q, Ma M. Urgent vs. non-urgent endoscopy in stable acute variceal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1125-1129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hsu YC, Chung CS, Tseng CH, Lin TL, Liou JM, Wu MS, Hu FC, Wang HP. Delayed endoscopy as a risk factor for in-hospital mortality in cirrhotic patients with acute variceal hemorrhage. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1294-1299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lee JG, Turnipseed S, Romano PS, Vigil H, Azari R, Melnikoff N, Hsu R, Kirk D, Sokolove P, Leung JW. Endoscopy-based triage significantly reduces hospitalization rates and costs of treating upper GI bleeding: a randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:755-761. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Schacher GM, Lesbros-Pantoflickova D, Ortner MA, Wasserfallen JB, Blum AL, Dorta G. Is early endoscopy in the emergency room beneficial in patients with bleeding peptic ulcer? A “fortuitously controlled” study. Endoscopy. 2005;37:324-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Risk assessment after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Gut. 1996;38:316-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 888] [Cited by in RCA: 896] [Article Influence: 30.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Blatchford O, Murray WR, Blatchford M. A risk score to predict need for treatment for upper-gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Lancet. 2000;356:1318-1321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 666] [Cited by in RCA: 684] [Article Influence: 27.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Kumar NL, Cohen AJ, Nayor J, Claggett BL, Saltzman JR. Timing of upper endoscopy influences outcomes in patients with acute nonvariceal upper GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:945-952.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hart A. Mann-Whitney test is not just a test of medians: differences in spread can be important. BMJ. 2001;323:391-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Thabut D, Bernard-Chabert B. Management of acute bleeding from portal hypertension. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;21:19-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Escorsell A, Ruiz del Arbol L, Planas R, Albillos A, Bañares R, Calès P, Pateron D, Bernard B, Vinel JP, Bosch J. Multicenter randomized controlled trial of terlipressin versus sclerotherapy in the treatment of acute variceal bleeding: the TEST study. Hepatology. 2000;32:471-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Escorsell A, Bordas JM, del Arbol LR, Jaramillo JL, Planas R, Bañares R, Albillos A, Bosch J. Randomized controlled trial of sclerotherapy versus somatostatin infusion in the prevention of early rebleeding following acute variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis. Variceal Bleeding Study Group. J Hepatol. 1998;29:779-788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | D'Amico G, Pagliaro L, Pietrosi G, Tarantino I. Emergency sclerotherapy versus vasoactive drugs for bleeding oesophageal varices in cirrhotic patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;CD002233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Cremers I, Ribeiro S. Management of variceal and nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2014;7:206-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Dai C, Liu WX, Jiang M, Sun MJ. Endoscopic variceal ligation compared with endoscopic injection sclerotherapy for treatment of esophageal variceal hemorrhage: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:2534-2541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Augustin S, González A, Genescà J. Acute esophageal variceal bleeding: Current strategies and new perspectives. World J Hepatol. 2010;2:261-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Sung JJ, Chung SC, Yung MY, Lai CW, Lau JY, Lee YT, Leung VK, Li MK, Li AK. Prospective randomised study of effect of octreotide on rebleeding from oesophageal varices after endoscopic ligation. Lancet. 1995;346:1666-1669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Laursen SB, Leontiadis GI, Stanley AJ, Møller MH, Hansen JM, Schaffalitzky de Muckadell OB. Relationship between timing of endoscopy and mortality in patients with peptic ulcer bleeding: a nationwide cohort study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:936-944.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Bernard B, Grangé JD, Khac EN, Amiot X, Opolon P, Poynard T. Antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of bacterial infections in cirrhotic patients with gastrointestinal bleeding: a meta-analysis. Hepatology. 1999;29:1655-1661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 594] [Cited by in RCA: 461] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2018;69:406-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1777] [Cited by in RCA: 1818] [Article Influence: 259.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 27. | Sarin SK, Kumar A, Angus PW, Baijal SS, Chawla YK, Dhiman RK, Janaka de Silva H, Hamid S, Hirota S, Hou MC. Primary prophylaxis of gastroesophageal variceal bleeding: consensus recommendations of the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver. Hepatol Int. 2008;2:429-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Cooper GS, Chak A, Way LE, Hammar PJ, Harper DL, Rosenthal GE. Early endoscopy in upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: associations with recurrent bleeding, surgery, and length of hospital stay. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:145-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Cooper GS, Kou TD, Wong RC. Use and impact of early endoscopy in elderly patients with peptic ulcer hemorrhage: a population-based analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:229-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Lim LG, Ho KY, Chan YH, Teoh PL, Khor CJ, Lim LL, Rajnakova A, Ong TZ, Yeoh KG. Urgent endoscopy is associated with lower mortality in high-risk but not low-risk nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2011;43:300-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |