Published online Nov 7, 2018. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i41.4691

Peer-review started: August 8, 2018

First decision: August 24, 2018

Revised: October 4, 2018

Accepted: October 16, 2018

Article in press: October 16, 2018

Published online: November 7, 2018

Processing time: 90 Days and 21.2 Hours

To determine if end-stage renal disease (ESRD) is a risk factor for post endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) adverse events (AEs).

We performed a retrospective cohort study using the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) 2011-2013. We identified adult patients who underwent ERCP using the International Classification of Diseases 9th Revision (ICD-9-CM). Included patients were divided into three groups: ESRD, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and control. The primary outcome was post-ERCP AEs including pancreatitis, bleeding, and perforation determined based on specific ICD-9-CM codes. Secondary outcomes were length of hospital stay, in-hospital mortality, and admission cost. AEs and mortality were compared using multivariate logistic regression analysis.

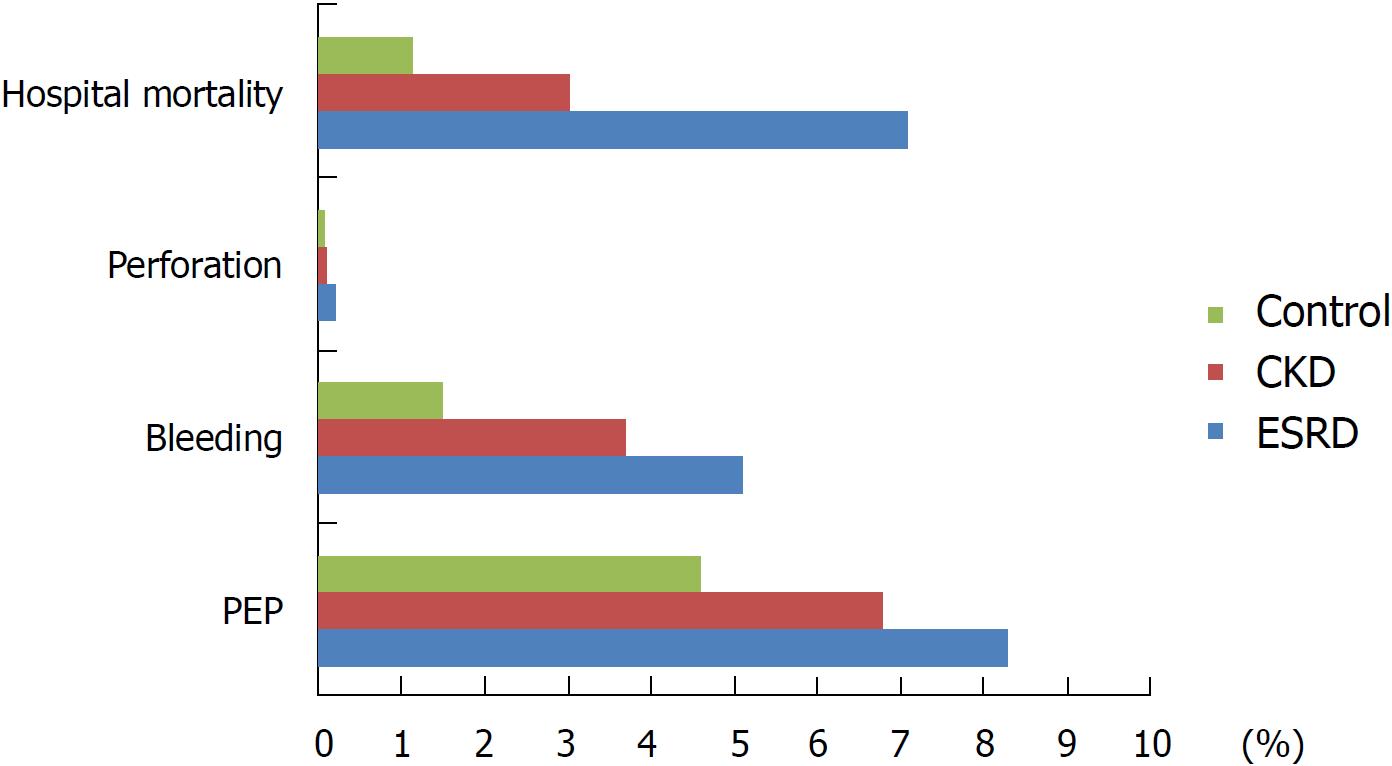

There were 492175 discharges that underwent ERCP during the 3 years. The ESRD and CKD groups contained 7347 and 39403 hospitalizations respectively, whereas the control group had 445424 hospitalizations. Post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP) was significantly higher in the ESRD group (8.3%) compared to the control group (4.6%) with adjusted odd ratio (aOR) = 1.7 (95%CI: 1.4-2.1, aP < 0.001). ESRD was associated with significantly higher ERCP-related bleeding (5.1%) compared to the control group 1.5% (aOR = 1.86, 95%CI: 1.4-2.4, aP < 0.001). ESRD had increased hospital mortality 7.1% vs 1.15% in the control OR = 6.6 (95%CI: 5.3-8.2, aP < 0.001), longer hospital stay with adjusted mean difference (aMD) = 5.9 d (95%CI: 5.0-6.7 d, aP < 0.001) and higher hospitalization charges aMD = $+82064 (95%CI: $68221-$95906, aP < 0.001).

ESRD is a risk factor for post-ERCP AEs and is associated with higher hospital mortality. Careful selection and close monitoring is warranted to improve outcomes.

Core tip: Recognizing risk factors for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)-related complications is essential to reduce adverse events (AEs). There are limited data evaluating ERCP outcomes in renal disease. In a retrospective cohort study using the Nationwide Inpatient Sample 2011-2013 and including 492175 discharges, we compared inpatient ERCP AEs, mortality and length of stay between patients with and without renal disease. We found end-stage renal disease (ESRD) to be associated with higher post ERCP pancreatitis [8.3%, adjusted odd ratio (aOR) = 1.7, aP < 0.001], bleeding (5.1%, aOR = 1.86, aP < 0.001), mortality (7.1%, aOR = 6.6, aP < 0.001) and longer hospital stay (5.9 d, aP < 0.001). Physicians should consider special interventions in ESRD patients to decrease ERCP AEs.

- Citation: Sawas T, Bazerbachi F, Haffar S, Cho WK, Levy MJ, Martin JA, Petersen BT, Topazian MD, Chandrasekhara V, Abu Dayyeh BK. End-stage renal disease is associated with increased post endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography adverse events in hospitalized patients. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(41): 4691-4697

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v24/i41/4691.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i41.4691

End-stage renal disease (ESRD) is an increasing, highly prevalent public health problem for which 660000 Americans are being treated. Of these, 468000 are on dialysis[1]. Patients with ESRD have increased bile cholesterol levels, high saturation index in the bile[2], and subsequently increased risk for gallstone formation. In addition, they are more prone to cholestasis secondary to autonomic dysfunction in uremia[3,4]. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is a safe, minimally invasive approach for pancreaticobiliary disease management. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) recently updated their guidelines on adverse events (AEs) associated with ERCP[5]. This guideline emphasized the importance of recognizing risk factors for ERCP-related complications, careful patient selection, and targeted maneuvers to reduce the risk of AEs. We hypothesized that ESRD might be a risk factor associated with higher ERCP-related AEs. Prior data have shown a higher risk of perforation during other endoscopic procedures such as colonoscopy among ESRD patients[6]. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a proven predictor of mortality in upper gastrointestinal bleeding[7,8]. However, there are limited published data evaluating AEs of ERCP in ESRD and CKD. Determining whether ESRD is a risk factor for ERCP-related AEs would guide endoscopists in efforts to undertake focused interventions to reduce the incidence of these AEs. The aim of our study was to evaluate ERCP-related AEs in ESRD and CKD, using a large national cohort.

We used the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) years 2011 through 2013 to conduct a cohort study. These years were chosen since they were the most recent years available at the time we conducted the analysis. The NIS is the largest all-payer inpatient database in the United States. Each year contains over 7 million inpatients regardless of their insurance from all community hospitals, excluding rehabilitation and long-term acute care hospitals, participating in the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The quality control procedures performed by HCUP have demonstrated reliability and accuracy, specifically pertaining to the principal diagnoses and dates of hospitalization. The year 2011 contained a 20% sample of the participating state’s hospitals then included all discharges from the selected hospitals. However, the sampling design was changed in the year 2012 and after to include a 20% sample of discharges from each hospital participating in HCUP from each state. We applied the trend weights provided by the NIS to combine the datasets from 2011 through 2013. The NIS data includes demographic variables (age, sex, race), up to 25 primary and secondary diagnoses, up to 15 primary and secondary procedures, hospital charges, and length of stay.

We included hospitalized patients age 18 years or older who underwent ERCP during their hospital stay. Discharges were identified using International Classification of Diseases 9th Revision (ICD-9-CM) for the ERCP procedure codes[9] (Supplementary Table 1). Included adult patients were divided into three groups using the ICD-9-CM codes. Study group 1 included patients with ESRD on dialysis; study group 2 included patients with CKD not on dialysis regardless of their stage. The control group was composed of patients without CKD or ESRD (Supplementary Table 2).

The primary outcome was post-ERCP AEs including post-ERCP pancreatitis, bleeding, and perforation. Secondary outcomes were length of hospital stay, in-hospital mortality, and admission cost. We isolated ERCP AEs from admission diagnosis by considering the primary and secondary diagnosis as indications (DX 1 and 2) and the subsequent diagnoses (DX 3-25) as AEs (Supplementary Table 3). Patients with primary or secondary diagnosis of acute pancreatitis were classified as acute pancreatitis not related to ERCP. Whereas, patients with acute pancreatitis codes from DX3-25 who did not have acute pancreatitis code in DX1 and 2 were considered post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP). This method was used and validated in prior studies[9,10]. Based on this methodology, the estimated percentage of PEP in this database was 4.8%, which is similar to the incidence previously reported in the literature[11,12]. Based on this we felt that the methodology accurately captured PEP. We assessed the severity of pancreatitis by respiratory and circulatory failure using the ICD-9 codes (Supplementary Table 3). Length of hospital stay, hospital mortality, and cost were provided by the NIS data. Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) was calculated and used to account for other comorbidities, as this has been demonstrated to be a well-validated measure of comorbidity adjusting for disease burden in administrative data[13]. We excluded CKD from CCI to avoid accounting for it twice in the adjusted analysis. However, we kept the full CCI score in the descriptive data (Table 1). CCI scores ranged from 0 to 17, with higher numbers representing a greater comorbidity burden. We also performed a subgroup analysis based on ERCP indication (diagnostic and therapeutic).

| ESRD, n = 7347 | Control, n = 445424 | P value | CKD, n = 39403 | P value | |

| Age, mean (SE), yr | 65.5 (0.42) | 58 (0.12) | < 0.001 | 75.35 (0.18) | < 0.001 |

| Female | 3477 (47.3) | 271300 (61) | < 0.001 | 17626 (44.7) | < 0.001 |

| Race | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||

| White | 3221 (43.8) | 280738 (63) | 26905 (68.3) | ||

| Black | 1520 (20.7) | 36875 (8.3) | 3517 (8.9) | ||

| Hispanic | 1467 (20) | 68492 (15.4) | 3729 (9.5) | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 454 (6.2) | 14081 (3.2) | 1466(3.7) | ||

| Native American | 105 (1.4) | 2828 (0.6) | 185 (0.5) | ||

| Other | 235 (3.2) | 14928 (3.3) | 982 (2.5) | ||

| Missing | 344 (4.7) | 27483 (6.2) | 2619 (6.6) | ||

| Charlson comorbidity index | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||

| 0 | 0 | 203229 (45.6) | 0 (0) | ||

| 1 | 0 | 104584 (23.5) | 0 (0) | ||

| 2 | 975 (13.3) | 55808 (12.5) | 6417 (16.3) | ||

| > 2 | 6372 (86.7) | 81804 (18.4) | 32986 (83.7) | ||

| Coagulopathy | 668 (9) | 15102 (3.4) | < 0.001 | 2633 (6.7) | < 0.001 |

| ERCP indication | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||

| Diagnostic | 1990 (27) | 102074 (22.9) | 9493 (24.1) | ||

| Therapeutic | 5257 (73) | 343350 (77.1) | 29910 (75.9) | ||

| Health insurance | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||

| Medicare | 5655 (77) | 189044 (42.7) | 31759 (80.7) | ||

| Medicare | 923 (9.9) | 59219 (13.4) | 1718 (4.4) | ||

| Private | 827 (11.3) | 142807 (32.3) | 4766 (12) | ||

| Self-pay | 40 (0.5) | 32785 (7.4) | 463 (1.2) | ||

| Others | 92 (1.3) | 18822 (4.2) | 670 (1.7) |

Baseline characteristics were presented as a percentage and mean (standard error) and compared using Chi-square test for nominal variables and the Student’s t-test for continuous ones. AEs were compared using univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis for dichotomous outcomes and linear regression for continuous outcomes. Odds ratios (ORs) and mean differences (MDs) were reported as crude and adjusted values controlling for baseline characteristics, which included age, sex, race, CCI, procedure indication, and health insurance. Discharge-levels sampling weights available in the database were applied to obtain national estimates representing discharges from all United States community hospitals. A trend weight was applied in the 2011 database to combine it with the 2012 and 2013 databases given the changes in the NIS survey design. Variables with more than 5% missing values were assigned a missing indicator level. A 2-sided aP-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA 14.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, United States)

We identified 492175 discharges who underwent ERCP during the 3 years on the nationwide level. The ESRD and CKD groups contained 7347 and 39403 hospitalizations respectively, whereas the control group had 445424 hospitalizations. Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. The control group included younger patients (mean age: 58 ± 0.12 years) and more women 61% compared to ESRD (mean age: 65.5 ± 0.42, females: 47.3%), and CKD (mean age: 75.35 ± 0.18, females: 44.7%).

Renal disease groups had higher CCI scores with over 80% of patients carrying a CCI > 2 compared to 18.4% with high CCI in the control group (aP < 0.001). Therapeutic intervention was the major indication for ERCP (> 70%) in all three groups. The majority of discharges in the ESRD and CKD were covered by Medicare insurance (71% and 81% respectively). In contrast, patients in the control group were divided among different types of health insurance, with a higher proportion covered by private insurance at 33%.

PEP was significantly higher in the ESRD group (8.3%) compared to the control group (4.6%) with adjusted OR (aOR) = 1.7 (95%CI: 1.4-2.1, aP < 0.001). The CKD group also had higher association with PEP (6.8% vs 4.6; aOR = 1.5, 95%CI: 1.3-1.7, aP < 0.001). Among discharges who developed PEP, the severity of the pancreatitis was worse among the ESRD and CKD group. More patients in the ESRD and CKD group with PEP required mechanical ventilation compared to the control group with aOR = 2.8 (95%CI: 1.7-4.9, aP < 0.001) and aOR = 1.5 (95%CI: 1.1-2.1, aP = 0.01), respectively. There was no difference in developing hypotension between the ESRD aOR = 1.4 (95%CI: 0.6-3.3, P = 0.5) or CKD aOR = 1.4 (95%CI: 0.9-2.3, P = 0.13) and the control group.

Additionally, ESRD was associated with significantly higher ERCP-related bleeding (5.1%) compared to the control group 1.5% (aOR = 1.86, 95%CI: 1.4-2.4, aP < 0.001) (Figure 1, Table 2). The CKD group had higher bleeding compared to the control group (3.7% vs 1.5%; aOR = 1.4, 95%CI: 1.2-1.6, aP < 0.001). Among the patients with ERCP-related bleeding, 51% of the ESRD and 46% of the CKD group required packed red blood (PRBC) transfusion compared to 40.5% in the control group (P = 0.1 and 0.13).

| Type of complications | ESRDn = 7347 | Controln = 445424 | CrudeOR/MD (95%CI) | AdjustedOR/MD (95%CI) | AdjustedP value |

| Death | 526 (7.1) | 5138 (1.15) | 6.6 (5.3-8.2) | 3.7 (2.9–4.6) | < 0.001 |

| Pancreatitis | 611 (8.3) | 20315 (4.6) | 1.9 (1.6-2.3) | 1.7 (1.4-2.1) | < 0.001 |

| Bleeding | 377 (5.1) | 6546 (1.5) | 3.6 (2.86-4.59) | 1.86 (1.4-2.4) | < 0.001 |

| Perforation | 14 (0.2) | 340 (0.07) | 2.6 (0.8–8.4) | 3 (0.86–10.00) | 0.08 |

| Length of hospital stay, mean days (SE) | 13 (0.46) | 6 (0.03) | 7.2 (6.4-8.0) | 5.9 (5.0-6.7) | < 0.001 |

There was no significant difference in perforation between the ESRD 0.2% or CKD group 0.1% and the control group 0.07% (aOR = 3, 95%CI: 0.86-10.00, P = 0.08) and (aOR = 1.36, 95%CI: 0.6-3.2, P = 0.5) respectively. Among discharges who had perforation, 34.6% needed surgical intervention in the ESRD compared to 12.6% in the control group (P = 0.5).

Hospital mortality was significant higher in the ESRD group compared to the control group (7.1% vs 1.15%; OR = 6.6, 95%CI: 5.3-8.2, aP < 0.001). Multivariate analysis controlling for other confounders, which could influence hospital mortality showed persistent higher hospital mortality in the ESD group (aOR = 3.7; 95%CI: 2.9-4.6, aP < 0.001) (Table 2). CKD was associated with higher hospital mortality as well, but to a lesser magnitude 3% with OR: 2.6 (95%CI: 2.3-3.0, aP < 0.001). Controlling for confounders, the hospital mortality aOR was 1.3 (95%CI: 1.14-1.6, aP < 0.001). Other predictors of higher hospital mortality from the multivariate analysis included age (aOR = 1.03 for each year, aP < 0.001), males (aOR = 1.2, aP < 0.001), black (aOR = 1.2 vs white, aP < 0.001), higher CCI (aOR = 8.1 for CCI > 2 compared to CCI = 0, aP < 0.001) and post ERCP AEs (aOR = 3.2, aP < 0.001). Hospital mortality among patients who developed post ERCP AEs, was significantly higher in the ESRD group (8%) compared to the control group who developed post ERCP AEs (2.5%), with an OR = 3.3 (95%CI: 1.5-7.1) and aOR = 2.7 (95%CI: 1.15-16.30, aP = 0.02).

Length of hospital stay was significantly longer in the ESRD group with mean length of stay of 13.00 ± 0.46 d compared to 6.00 ± 0.03 d in the control, and adjusted mean difference (aMD) = 5.9 d (95%CI: 5.0-6.7 d, aP < 0.001) (Table 2). The CKD group had significantly longer hospital stay with mean length of stay of 8.50 ± 0.11 d compared to the control group aMD = 1.4 d (95%CI: 1.20-1.65 d, aP < 0.001) (Table 3).

| Type of complications | CKDn = 39403 | Controln = 445424 | CrudeOR/MD (95%CI) | AdjustedOR/MD (95%CI) | AdjustedP value |

| Death | 1176 (3) | 5138 (1.15) | 2.6 (2.3-3.0) | 1.3 (1.14-1.55) | 0.001 |

| Pancreatitis | 750 (6.8) | 20315 (4.6) | 1.5 (1.3-1.6) | 1.5 (1.3-1.7) | < 0.001 |

| Bleeding | 1454 (3.7) | 6546 (1.5) | 2.56 (2.25–2.90) | 1.4 (1.2-1.6) | < 0.001 |

| Perforation | 43 (0.1) | 340 (0.07) | 1.4 (0.7–2.9) | 1.36 (0.6–3.2) | 0.5 |

| Length of hospital stay, mean days (SE) | 8.5 (0.11) | 6 (0.03) | 2.45 (2.24-2.67) | 1.4 (1.20-1.65) | < 0.001 |

ESRD patients incurred higher hospitalization charges: $156577 per discharge (SE: $7952) compared to $61583 (SE: $778) in the control group (aMD = $+82064; 95%CI: $68221-$95906, aP < 0.001).

Other factors associated with higher hospital cost included male (MD = $+7333, 95%CI: $5909-$8756, aP < 0.001), race (white and native American races had less charge compared to other races), higher comorbidities and post ERCP AEs. ESRD who developed post ERCP AEs had significantly higher charge compared to ESRD without ERCP AEs aMD = $133892 (95%CI: $76575-$191209, aP < 0.001) supporting that AEs were responsible for significant portion of the higher cost in the ESRD. CKD patients incurred higher hospital charges $83714 per discharge (SE: $1821) with aMD: $14482 compared to the control group (95%CI: $11531- $17432, aP < 0.001).

We performed a subgroup analyses to assess the effect of ERCP indication (therapeutic vs diagnostic) on our outcomes. ESRD and CKD were associated with PEP and bleeding when ERCP was performed for therapeutic indications only but not for diagnostic purposes. There was no increased association with perforation in either group for therapeutic ERCP (Supplementary Table 4). Perforation was extremely rare in diagnostic ERCP and so a measure of association was not performed.

In the ESRD group, hospital mortality, and length of stay were still higher for both therapeutic and diagnostic ERCP (Supplementary Table 4). Patients with CKD who were not on HD demonstrated higher associations with hospital mortality when they underwent therapeutic ERCP only. Length of hospital stay was higher in for both indications.

In this nationwide study, we investigated ERCP-related AEs in patients with ESRD and CKD in hospitalized patients. Compared to the control group, ESRD and CKD were associated with higher post-ERCP AEs including PEP and bleeding. Furthermore, ESRD and CKD were associated with longer hospital stay, higher hospital mortality, and greater cost compared to the control. When AEs developed, ESRD was associated with more complications including higher requirement for mechanical ventilation and surgical intervention. These findings were true among patients who underwent therapeutic ERCP. We did not notice higher AEs from diagnostic ERCP in either ESRD or CKD.

PEP is a serious and most common complication of ERCP[14]. Several risk factors were proven to be associated with increased risk for PEP[5]. Some of these factors are patient-dependent, such as age, gender, and history of PEP. Others are procedure-dependent. Recognizing these risk factors is important to provide appropriate preventive measures[5]. Our findings suggest that ESRD and CKD patients are at increased risk for PEP. One possible theory behind the increased association between ESRD and PEP may be papillary edema from fluid overload posing difficult biliary cannulation[5]. In a previous study of 76 patients with ESRD who underwent ERCP in Japan, the incidence of PEP was 7.9%[15]. Their mortality from PEP was 1/6 (16.7%). In our current study, hospital mortality among ESRD patients who developed PEP was 7.9%. We also found significant increase in the requirement of mechanical ventilation among patients with ESRD. This reflects the challenge of managing PEP in dialysis patients. Pancreatitis management is mainly dependent on early volume support. Dialysis patients are at risk for fluid overload and respiratory failure from fluid replacement. On the other hand, inadequate fluid support will accelerate end organ damage, resulting in a high risk of death. The strong association between PEP and mortality requires physicians to enact measures sufficient to assure better outcomes. Appropriate patient selection is always important and even more so in high-risk patients to prevent PEP and other AEs. When feasible, other diagnostic imaging modalities such as magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) and endoscopic ultrasound should be considered first, reserving ERCP largely for therapeutic indications. While these principles are true for all patients, they should be followed methodically in patients considered high-risk for post-ERCP AEs, including patients on dialysis.

In a study by Hori et al[15], ERCP-related bleeding was noted in 5.3% of patients with ESRD on dialysis. This is similar to our study where ERCP related bleeding complicated 5.1% of ESRD undergoing ERCP. The increased association with bleeding might be due to platelets dysfunction and coagulopathy secondary to uremia. The severity of bleeding, however, seemed to be similar between the ESRD and the control group as the need for blood transfusion was not significantly different. Endoscopic papillary balloon dilation for bile duct stones was evaluated as a possible method to minimize the risk for bleeding in patients on hemodialysis. Takahara et al[16] found that the risk of bleeding using the balloon papillary dilation was 5.4%. However, all bleeding occurred in patients who had other risk factor beside renal disease.

Perforation is an uncommon complication of ERCP. The reported incidence of post-ERCP perforation is between 0.08%-0.6%[5,17]. Perforation is usually secondary to luminal perforation from the scope, extension of sphincterotomy cut, or bile duct perforation secondary to the guidewire penetration outside the lumen[5]. In the current study, we found no significant increase in perforation associated with ERCP in ESRD or CKD. The need for surgical intervention to manage perforation was also similar between the groups.

Hospital mortality was significantly higher in the ESRD group (7.1%). The elevation in mortality can be attributed to the high AEs, comorbidities and challenges associated with management of ESRD patients. Post-ERCP mortality in dialysis patients was reported in another study to be only 2.6%[15]. The lower mortality in that study might be attributed to different health care settings. Our study included hospitalized patients, of whom 75% underwent therapeutic ERCP. In the study by Hori et al[15], ERCP was performed in different settings, with 68% of patients undergoing therapeutic ERCP.

Finally, we found significantly higher admission cost associated with ESRD, which might be driven in part by the dialysis cost. However, AEs and longer hospital stay might also have contributed to the substantially higher charges. In fact, when we compared hospital charges between ESRD who developed AEs and those who did not, we found that the majority of the cost (MD: $133892) was from the AEs.

Our study has several inherent limitations. First, we used ICD-9-CM codes to identify patients who underwent ERCP, those with renal disease, and their outcomes, thus our study is subject to the limitations implied by these codes. However, we applied similar methods to previously validated published data, using administrative codes to appropriately capture our population and outcomes. Second, distinguishing procedure AEs from indications is challenging. We considered DX 1 and 2 as indication and DX 3-25 as AEs. We feel that we appropriately captured these AEs since the association with post-ERCP AEs and mortality in our control group were similar to the ones reported in the literature. Third, this is a cohort retrospective study, with inherent limitations including residual confounders, which could have affected our outcomes. Fourth, there is potential for recording bias, as chronic conditions may be under-coded in severely ill patients. Fifth, the NIS does not include data about patients who developed AEs after discharge. Readmissions are not captured; therefore, complication rates might be underestimated.

In conclusion, ESRD is associated with a higher associated with ERCP related AEs and with significant health care burden in hospitalized patients requiring ERCP. Based on our findings, we suggest closer monitoring for ESRD patients undergoing ERCP. Physicians might consider special peri-procedure interventions in ESRD patients in efforts to decrease AEs including careful patient selection, optimization of fluid volume status and use of various prophylactic or therapeutic endoscopic interventions, with closer observation after ERCP. Additional prospective studies are needed to investigate the value of any particular intervention in improving clinical outcomes following ERCP in this high-risk population.

End-stage renal disease (ESRD) is associated with increased risk for biliary diseases. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is the standard treatment for most biliary diseases. Prior data have shown renal disease to be a risk factor for perforation during other endoscopic procedures such as colonoscopy and a proven mortality predictor in upper gastrointestinal bleeding. There are limited published data evaluating ERCP outcomes in ESRD.

The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) guideline emphasized the importance of recognizing risk factors for ERCP-related complications, careful patient selection, and targeted maneuvers to reduce the risk of adverse events (AEs). We hypothesized that ESRD is associated with higher ERCP AEs. This would guide endoscopists in efforts to undertake focused interventions to reduce the incidence of these AEs.

The main objective of our study is to evaluate ERCP outcomes in ESRD using a large national cohort. We evaluated the association between ESRD and AEs, hospital mortality, length of stay and cost.

In a retrospective cohort study using the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) years 2011-2013 and including 492175 discharges, we compared inpatient ERCP AEs between patients with ESRD and individuals without renal diseases. We compared ERCP outcomes using logistic regression model and applying appropriate weighted sampling design.

ESRD was associated with higher AEs including post ERCP pancreatitis [8.3%, adjusted odd ratio (aOR) = 1.7, aP < 0.001] and bleeding (5.1%, aOR = 1.86, aP < 0.001) compared to patients without renal disease. ESRD was also associated with higher hospital mortality (7.1%, OR = 6.6, aP < 0.001) and longer hospital stay [mean difference (MD) = 5.9 d, aP < 0.001]. The remaining problem is identifying appropriate interventions to minimize AEs in this high-risk group

ESRD is associated with higher post ERCP AEs and hospital mortality and longer hospital stay. The current study emphasizes on the importance of identifying risk factors for ERCP AEs and include ESRD as a one these factors. Based on these findings, physicians might consider special peri-procedure interventions in ESRD patients in efforts to decrease AEs including careful patient selection, optimization of fluid volume status and use of various prophylactic or therapeutic endoscopic interventions, with closer observation after ERCP.

ESRD is associated with higher ERCP AEs, higher mortality and longer hospital stay. Additional prospective studies are needed to investigate the value of any particular intervention in improving clinical outcomes following ERCP in this high-risk population.

We greatly thank Dr. Daniel Singer from Harvard TH Chan School of public health for his valuable input regarding the methodology.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Altonbary A, Dhaliwal HS, Koksal AS, Nakai Y S- Editor: Ma RY L- Editor: A E- Editor: Yin SY

| 1. | United States Renal Data System. 2015 USRDS annual data report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. Accessed August 6, 2018 Available from: URL: https://www.usrds.org/2015/download/vol2_USRDS_ESRD_15.pdf. . |

| 2. | Marecková O, Skála I, Marecek Z, Malý J, Kocandrle V, Schück O, Bláha J, Prát V. Bile composition in patients with chronic renal insufficiency. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1990;5:423-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Pauletzki J, Althaus R, Holl J, Sackmann M, Paumgartner G. Gallbladder emptying and gallstone formation: a prospective study on gallstone recurrence. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:765-771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Duane WC. Something in the way she moves: gallbladder motility and gallstones. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:823-825. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Chandrasekhara V, Khashab MA, Muthusamy VR, Acosta RD, Agrawal D, Bruining DH, Eloubeidi MA, Fanelli RD, Faulx AL, Gurudu SR, Kothari S, Lightdale JR, Qumseya BJ, Shaukat A, Wang A, Wani SB, Yang J, DeWitt JM. Adverse events associated with ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:32-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 405] [Cited by in RCA: 529] [Article Influence: 66.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Imai N, Takeda K, Kuzuya T, Utsunomiya S, Takahashi H, Kasuga H, Asai M, Yamada M, Tanikawa Y, Goto H. High incidence of colonic perforation during colonoscopy in hemodialysis patients with end-stage renal disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:55-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Risk assessment after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Gut. 1996;38:316-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 888] [Cited by in RCA: 894] [Article Influence: 30.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sood P, Kumar G, Nanchal R, Sakhuja A, Ahmad S, Ali M, Kumar N, Ross EA. Chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease predict higher risk of mortality in patients with primary upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Nephrol. 2012;35:216-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Inamdar S, Berzin TM, Sejpal DV, Pleskow DK, Chuttani R, Sawhney MS, Trindade AJ. Pregnancy is a Risk Factor for Pancreatitis After Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography in a National Cohort Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:107-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yadav D, O’Connell M, Papachristou GI. Natural history following the first attack of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1096-1103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 243] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 11. | Masci E, Toti G, Mariani A, Curioni S, Lomazzi A, Dinelli M, Minoli G, Crosta C, Comin U, Fertitta A. Complications of diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP: a prospective multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:417-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 625] [Cited by in RCA: 613] [Article Influence: 25.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, Moore JP, Fennerty MB, Ryan ME, Shaw MJ. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1716] [Cited by in RCA: 1687] [Article Influence: 58.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 13. | Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7532] [Cited by in RCA: 8635] [Article Influence: 261.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Christensen M, Matzen P, Schulze S, Rosenberg J. Complications of ERCP: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:721-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 305] [Cited by in RCA: 299] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hori Y, Naitoh I, Nakazawa T, Hayashi K, Miyabe K, Shimizu S, Kondo H, Yoshida M, Yamashita H, Umemura S. Feasibility of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography-related procedures in hemodialysis patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:648-652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Takahara N, Isayama H, Sasaki T, Tsujino T, Toda N, Sasahira N, Mizuno S, Kawakubo K, Kogure H, Yamamoto N. Endoscopic papillary balloon dilation for bile duct stones in patients on hemodialysis. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:918-923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cotton PB, Garrow DA, Gallagher J, Romagnuolo J. Risk factors for complications after ERCP: a multivariate analysis of 11,497 procedures over 12 years. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:80-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 449] [Cited by in RCA: 465] [Article Influence: 29.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |