Published online Oct 28, 2018. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i40.4578

Peer-review started: July 19, 2018

First decision: August 25, 2018

Revised: September 11, 2018

Accepted: October 5, 2018

Article in press: October 5, 2018

Published online: October 28, 2018

Processing time: 100 Days and 0 Hours

To investigate the efficacy and safety of endoscopic stent insertion in patients with delayed gastric emptying after gastrectomy.

In this study, we prospectively collected data from patients who underwent stent placement for delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after distal gastrectomy between June 2010 and April 2017, at a tertiary referral academic center. Clinical improvement, complications, and consequences after stent insertion were analyzed.

Technical success was achieved in all patients (100%). Early symptom improvement was observed in 15 of 20 patients (75%) and clinical success was achieved in all patients. Mean follow-up period was 1178.3 ± 844.1 d and median stent maintenance period was 51 d (range 6-2114 d). During the follow-up period, inserted stents were passed spontaneously per rectum without any complications in 14 of 20 patients (70%). Symptom improvement was maintained after stent placement without the requirement of any additional intervention in 19 of 20 patients (95%).

Endoscopic stent placement provides prompt relief of obstructive symptoms. Thus, it can be considered an effective and safe salvage technique for post-operative DGE.

Core tip: Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after distal gastrectomy is a significant postoperative complication, and appropriate treatment measures are not yet available. This retrospective study investigated the efficacy and safety of self-expandable metallic stents in patients with DGE after gastric surgery. We found that endoscopic stent placement provided prompt relief of obstructive symptoms, with a low rate of complications, and no need for additional surgical interventions.

- Citation: Kim SH, Keum B, Choi HS, Kim ES, Seo YS, Jeen YT, Lee HS, Chun HJ, Um SH, Kim CD, Park S. Self-expandable metal stents in patients with postoperative delayed gastric emptying after distal gastrectomy. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(40): 4578-4585

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v24/i40/4578.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i40.4578

Gastric cancer is one of the most common types of gastrointestinal malignancies. Every year, 950000 people are newly diagnosed with gastric cancer and 700000 gastric cancer-related deaths occur[1-4]. Although endoscopic therapy is a useful and effective therapeutic modality for early gastric cancer, to date the only curative treatment option has been surgical resection. Recently, laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy, which is less invasive than conventional gastrectomy, with or without lymph node dissection, has become the mainstay of surgical management. With minimally invasive surgery becoming popular, the quality of life after surgical resection has improved[5-9]. Despite the use of advanced techniques, complications related to surgery are unavoidable. After gastric resection, bowel recovery can be delayed in a proportion of patients. Postgastrectomy syndromes, such as reflux esophagitis and dumping syndrome, can occur after distal gastrectomy. These complications are closely associated with the frequency of gastric emptying[10,11]. Moreover, longstanding gastric stasis following gastric resection can occur occasionally. The prevalence of postoperative delayed gastric emptying (DGE) has been shown to be between 5% and 30%[12-14]. It is characterized by an inability to consume regular meals with no evidence of anatomical narrowing or obstruction. Functional abnormality or inflammation at the anastomotic site could also lead to postoperative DGE. Sometimes, DGE may be associated with major postoperative adverse events, such as pancreatitis or pneumonia, and truncal vagotomy[12]. Moreover, it is likely that there are other unknown causes that cannot be clinically explained.

The primary therapeutic approach for postoperative DGE could be observation with nutritional support and administration of prokinetics. Reoperation to treat postoperative DGE is performed only in patients exhibiting severe and longstanding symptoms of outlet obstruction, necessitating drainage or non-oral route feeding[14,15]. However, there have been no suitable recommendations for the treatment of postoperative DGE.

Recently, self-expandable metallic stent (SEMS) placement has emerged as an effective and practical method not only for the management of gastrointestinal malignancy-associated narrowing or obstruction but also for benign stenosis or leaks of the gastrointestinal tract[16-18]. To the best of our knowledge, there has been no study mentioning the efficacy and safety of SEMS in patients with DGE after gastrectomy. We assumed that SEMS placement in the outlet area may facilitate rapid resumption of oral intake of foods and recovery of general patient conditions, resulting in a shorter hospital stay in patients with DGE after gastrectomy. We analyzed and described our experience with SEMS placement in patients with DGE exhibiting longstanding obstructive symptoms after gastrectomy.

We prospectively collected data from June 2010 to April 2017. The total number of distal gastrectomies performed during the same period was 891. Twenty patients (2.2%) underwent stent insertion for postoperative DGE. DGE was defined as the failure to consume and/or tolerate a regular diet even after the seventh postoperative day[14,19,20]. We enrolled postoperative DGE patients who were not responsive to conservative management. Patients were kept “nil per oral” (NPO) and received conservative management with nutritional support and administration of prokinetics before stent placement.

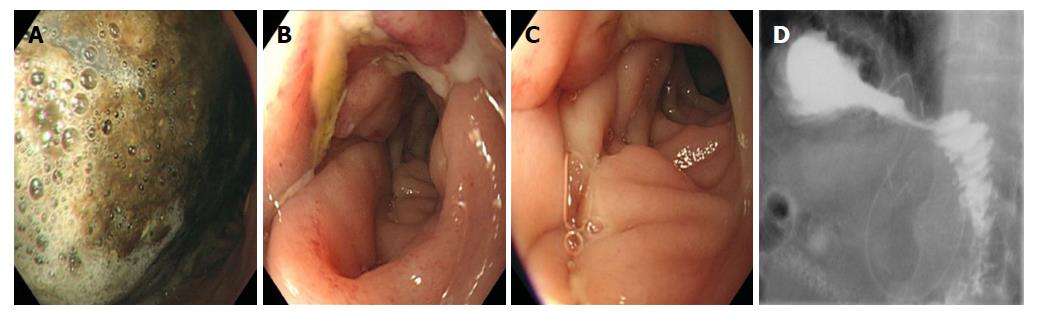

For each case, we recorded the diagnosis, type of gastric procedure performed, hospital course, postoperative day when oral food intake was resumed, and postoperative problems. All patients were assessed using gastroscopy and upper gastrointestinal (UGI) series with gastrografin during diagnosis and treatment (Figure 1).

Patients who were suspected of DGE, but did not undergo gastroscopy or UGI series testing, were excluded from the study. This study was reviewed by and ethical approval was obtained from the Korea University Anam Hospital Institutional Review Board (IRB No. ED13047).

Procedures were performed according to standard treatment algorithms[21]. Laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy (LADG) was performed by two surgeons with considerable experience with the procedure. During surgery, resection was performed, leaving an adequate resection margin. D2 lymph node dissection was performed according to guidelines in all patients. Reconstruction after gastrectomy was performed using one of the following reconstruction methods depending on the surgeon’s preference: (1) Billroth I gastroduodenostomy and (2) Billroth II gastrojejunostomy. During surgery, the vagal nerve was preserved because it has been shown to be helpful in improving the quality of life after gastrectomy by decreasing the occurrence of diarrhea and formation of postgastrectomy gallstones[22]. All surgical procedures were performed under general anesthesia. Postoperative oral food intake was permitted following the first bowel movement.

The stent (M. I. Tech, Seoul, South Korea) diameters ranged from 18-20 mm and were 70-, 90-, and 110-mm long. All SEMSs used were partially covered; their central body portion was covered with a silicone membrane and the flared portions of both ends were bare. The length of the stent was determined by the endoscopist based on the appearance of gastrojejunostomy anastomotic site and the efferent loop.

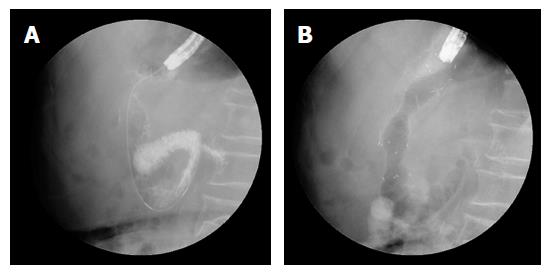

Endoscopic stent deployment was performed using a GIF-2TQ260M endoscope (Olympus Optical Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). An experienced endoscopist performed stent placement following a combined fluoroscopic and endoscopic method (Figure 2). Stent placement was performed according to the procedural details described previously[23]. All procedures were performed under standard conscious sedation using propofol and/or midazolam. Patients were maintained in either the left decubitus or prone position during stent placement.

We defined technical success of stent placement as the adequate deployment of the stent at the anastomosis site. Satisfactory relief of gastric stasis at 14 d was defined as clinical success, after which resumption of oral intake was possible. Early symptom improvement was defined as oral intake resumption within 2 d following stent placement.

Patients were followed up until they were lost to follow-up or dead. During follow-up, symptom improvement was evaluated by gastroscopy, interviews with patients, and abdominal radiographic examination. Patient symptoms and obstructive signs were monitored and used to identify stent failure. When stent failure was suspected, endoscopic assessment and abdominal radiography were performed to evaluate patency. Data were acquired from endoscopic findings, radiologic reports, and clinical records.

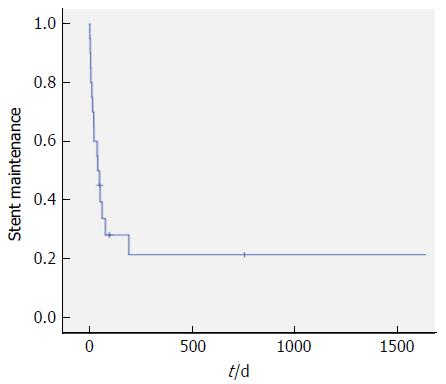

Data are shown as mean, median, standard deviation, and percentages. The stent maintenance period determined during follow-up was assessed by Kaplan-Meier analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States).

The mean patient age was 65.9 ± 11.4 years (range 35-82 years) (Table 1). Gastroscopic examination presented no mechanical obstruction or stricture of the anastomotic site in any patient, and the gastroscope could freely pass through the gastroenteric anastomosis. The UGI series showed contrast passage delay through the anastomosis, but no obvious mechanical obstruction, stricture, or leakage of anastomosis was observed. Baseline gastric outlet obstruction scoring system (GOOSS) scores suggested that patients had adjusted their diet to compensate for DGE (Table 2).

| Variable | Number of patients |

| Sex | |

| Male | 13 (65) |

| Female | 7 (35) |

| Comorbidity | |

| DM | 6 (30) |

| HTN | 7 (35) |

| Psychological disorder | 3 (15) |

| Histologic type | |

| Well differentiated | 3 (15) |

| Moderately differentiated | 5 (25) |

| Poorly differentiated | 12 (60) |

| Tumor location | |

| Body | 9 (45) |

| Antrum | 11 (55) |

| Operation method | |

| LADG, B-I | 10 (50) |

| LADG, B-II | 10 (50) |

| Characteristic | Number of patients |

| GOOSS score | |

| No oral intake (0) | 5 (25) |

| Only liquid diet (1) | 10 (50) |

| Soft solid diet (2) | 5 (25) |

| Low residue or normal diet (3) | 0 (0) |

| Obstructive symptom | |

| Abdominal pain | |

| None | 7 (35) |

| Moderate | 12 (60) |

| Severe | 1 (5) |

| Vomiting | |

| None | 5 (25) |

| Moderate | 10 (50) |

| Severe | 5 (25) |

| Nausea | |

| None | 3 (15) |

| Moderate | 11 (55) |

| Severe | 6 (30) |

| Regurgitation | |

| None | 5 (25) |

| Moderate | 10 (50) |

| Severe | 5 (25) |

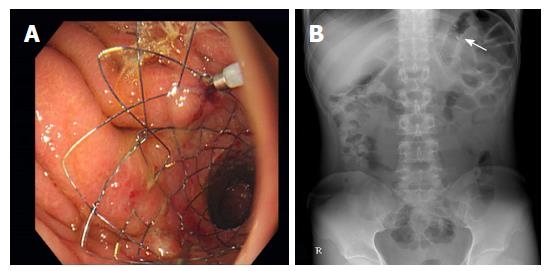

A total of 20 patients underwent stent placement for DGE after distal gastrectomy (Figure 3). Technical success was achieved in all patients (100%). Procedures were performed using forward-viewing gastroscopes in all patients. The most frequently deployed stent length was 90 mm (65%), followed by 70 mm (25%) and 110 mm (10%) (Table 3). After stent placement, patients remained hospitalized for a mean of 6.8 ± 4.6 d (range 2-21 d).

| Patient No. | Tumor location | Operation type | Stent type | Duration for Symptom improvement | Stent patency | Duration from operation to stent placement | Hospital stay after stent insertion | Total hospital stay |

| 1 | Antrum | LADG (B-I) | 90-mm covered stent | 2 | 758 | 17 | 7 | 31 |

| 2 | Antrum | LADG (B-I) | 90-mm covered-stent | 3 | 80 | 25 | 5 | 34 |

| 3 | Mid body | LADG (B-I) | 70-mm covered stent | 1 | 2114 | 28 | 7 | 38 |

| 4 | Low body | LADG (B-II) | 90-mm covered stent | 2 | 54 | 27 | 6 | 35 |

| 5 | Low body | LADG (B-I) | 90-mm covered stent | 2 | 17 | 31 | 3 | 36 |

| 6 | Body | LADG (B-II) | 70-mm covered stent | 6 | 6 | 26 | 10 | 37 |

| 7 | Antrum | LADG (B-II) | 110-mm covered stent | 5 | 194 | 23 | 13 | 42 |

| 8 | Body | LADG (B-I) | 90-mm covered stent | 3 | 9 | 28 | 12 | 42 |

| 9 | Antrum | LADG (B-II) | 70-mm covered stent | 2 | 14 | 14 | 4 | 25 |

| 10 | Antrum | LADG (B-II) | 90-mm covered stent | 1 | 98 | 12 | 5 | 21 |

| 11 | Antrum | LADG (B-I) | 90-mm covered stent | 5 | 8 | 24 | 8 | 35 |

| 12 | Low body | LADG (B-I) | 70-mm covered stent | 1 | 1675 | 7 | 2 | 21 |

| 13 | Body | LADG (B-II) | 110-mm covered stent | 2 | 24 | 14 | 6 | 23 |

| 14 | Antrum | LADG (B-II) | 90-mm covered stent | 2 | 40 | 9 | 8 | 25 |

| 15 | Antrum | LADG (B-I) | 90-mm covered stent | 1 | 51 | 15 | 3 | 20 |

| 16 | Antrum | LADG (B-II) | 90-mm covered stent | 1 | 42 | 23 | 2 | 27 |

| 17 | Body | LADG (B-II) | 90-mm covered stent | 1 | 64 | 11 | 21 | 35 |

| 18 | Body | LADG (B-I) | 90-mm covered stent | 1 | 23 | 21 | 3 | 31 |

| 19 | Antrum | LADG (B-II) | 90-mm covered stent | 1 | 4 | 9 | 9 | 19 |

| 20 | Antrum | LADG (B-II) | 70-mm covered stent | 0 | 52 | 9 | 2 | 21 |

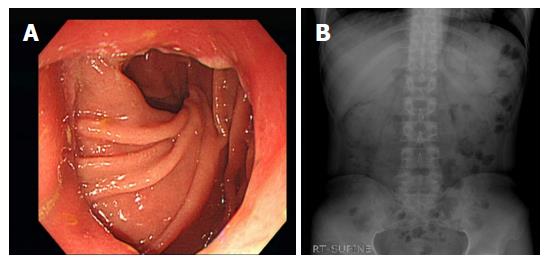

Stent patency at 14 d was 80% (16 patients). Before the 14th d follow-up, four patients experienced stent migration, but they had no significant symptoms and did not need further intervention. Mean follow-up period was 1178.3 ± 844.1 d (Figure 4). Stent maintenance period determined during follow-up was assessed by Kaplan-Meier analysis (Figure 5). The median stent maintenance duration was 51 d (range 6-2114 d). In a patient with preserved stent maintenance, 1-year follow-up gastroscopy revealed a slightly stenotic anastomotic site with a metal stent, but the gastroscope could be passed. Granulation tissue was observed around the anastomotic site.

During the study, over 90% of patients experienced relief in the obstructive symptoms after stent placement compared with the baseline obstructive symptoms (Table 4). After stent placement, early symptom improvement was achieved in 15 of 20 patients (75%). The rate of clinical success 14 d after stent placement was 100%. During the follow-up period, inserted stents were spontaneously passed per rectum in 14 of 20 patients (70%) and no significant complications were noted. Moreover, symptom improvement was maintained after stent placement without the requirement of any additional stent or surgical procedure in 19 of 20 patients (95%).

| Characteristics | 1 yr | 2 yr | 3 yr | 4 yr | 5 yr |

| Number of patients available for follow-up | 15 | 10 | 8 | 7 | 3 |

| Patients with all symptoms maintained or improved compared with baseline (%) | 93 | 90 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Patients with any symptom worsening compared to baseline (%) | 7 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

There was no procedure- or device-associated mortality in this study. After stent placement, there were no immediate adverse events, such as perforation or aspiration pneumonia (Table 5). The most common GI adverse event was stent migration. Stent migration occurred between 6 and 194 d after stent placement. Most of the migrated stents spontaneously passed per rectum. In one patient, the stent had migrated into the stomach, and stent extraction was performed with rat tooth forceps. In another patient, a stent fracture was noted and an additional stent was inserted immediately. Two further patients experienced severe abdominal pain. All these events were considered to be associated with postsurgical bowel adhesion and were not stent related. There was no adverse event caused by distal stent migration.

| Adverse event | Total number of events | % of patients | Stent-related events | % of patients |

| Stent occlusion | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| GI bleeding | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bowel perforation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Severe abdominal pain | 2 | 11.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Stent migration | 15 | 83.3 | 15 | 93.7 |

| Stent fracture | 1 | 5.6 | 1 | 6.3 |

| Total | 18 | 100 | 16 | 100 |

In the present study, we evaluated the efficacy of SEMS insertion for DGE following surgical gastrectomy. Endoscopic stent placement provides prompt relief of obstructive symptoms.

During the first 1-3 wk after distal gastrectomy, postoperative DGE can occur due to different potential causes[12-14]. Of these, a mechanical problem may be the cause of the persistent increase in gastric remains. Acute angulation, kinking, long-term edema, or congestion of anastomotic lesions may also cause postoperative DGE. To date, various therapeutic approaches have been used for the treatment of postoperative DGE[19,20]. Although initial observation with conservative management including non-oral-route nutritional support is preferred, it is difficult for patients to maintain NPO status for more than 2-3 wk. Moreover, there is no appropriate way to evaluate the degree of improvement of DGE; thus, decision-making regarding treatment continuation or termination is difficult. Reoperation might be performed in situations in which nutritional support by a feeding jejunostomy is needed or when an efferent limb or stomal obstruction occurs[12]. However, reoperation increases the risk of morbidity and mortality, although it might appear to be more effective than conservative treatment. The current methods for postoperative DGE might therefore present less effective outcomes or potential morbidity associated with medications or surgical procedures.

If DGE in a patient improves after a short duration of conservative management, further therapeutic planning is not needed. If not, the subsequent therapeutic step needs to be planned. It is often preferable not to select surgery directly, but to plan a bridge or substitutive therapy that can likely fill the gap. In such a clinical situation, stent placement could be ideal, compared with medical conservative treatment or reoperation.

In this study, stent placement rapidly resolved obstructive symptoms without severe adverse events and the patient could be discharged with resumption of oral intake within a short duration after stent insertion. The stenting procedure itself is a minimally invasive therapeutic approach, which can be performed using simple fluoroscopy-guided endoscopy. Although experts are required for stent insertion, it is a relatively simple procedure. After stent insertion, patients did not require prolonged fasting or hospitalization, while the quality of life of patients improved, and adverse events did not occur. We did not need to remove the inserted stent in any patient. Deployed stents were passed per rectum spontaneously after some time. There were no associated complications.

At present, literature concerning stent placement for DGE after surgical gastrectomy is scarce. Stent deployment in patients with DGE after distal gastrectomy in this study resulted in effective and favorable outcomes. It is difficult to determine an optimal time for stent removal as early removal may decrease the effect of stenting and late removal could induce stent ingrowth. Therefore, we did not make a fixed decision regarding the appropriate timing of stent extraction. We did not extract the deployed stent because we believed that it would be better if it remained in position for as long as possible. We performed endoscopic clipping at the proximal end of the stent to prevent immediate migration after stent placement as there was no anatomical stenosis that would induce mechanical obstruction. When the stent migrated, it was passed per rectum spontaneously without any adverse events and did not need any surgical procedure.

Considering these results, physicians should consider stent placement in patients with postoperative DGE, especially, when rapid oral diet resumption could be helpful for patients. This method can relieve obstructive symptoms rapidly, shorten hospital stay, and increase patient satisfaction, and quality of life.

In conclusion, endoscopic stent placement resulted in a high technical success rate and rapid symptom improvement in patients with postoperative DGE. Further surgical intervention was not necessary in all cases. Endoscopic stenting could be considered a useful treatment option for DGE after gastrectomy.

Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after gastric surgery is one of the main postoperative complications. However, there have been no appropriate treatment measures for this distressing clinical situation. Recently, self-expandable metallic stent (SEMS) placement has become an effective and practical method not only for the management of gastrointestinal malignancy-associated problems but also for benign stenosis or leaks of the gastrointestinal tract.

The currently available methods for postoperative DGE might present less effective outcomes or potential morbidities associated with medications or surgical procedures.

The objective of this study was to analysis whether SEMS placement in the outlet area may facilitate rapid resumption of oral food intake and recovery of the general condition, resulting in shorter hospital stays in patients with DGE after gastrectomy.

We prospectively collected data from 20 patients who underwent stent insertion for postoperative DGE. We recorded the diagnosis, type of gastric procedure performed, hospital course, postoperative day when oral food intake was resumed, and postoperative problems. Assessment for clinical improvement, complications, and consequences after stent insertion were performed.

Stent placement for postoperative DGE relieved obstructive symptoms rapidly, shortened hospital stay, and increased patient satisfaction and quality of life. Endoscopic stent placement presented a high technical success rate and rapid symptom improvement in patients with postoperative DGE. Moreover, no further surgical procedures were necessary in all cases. Endoscopic stenting could be considered a useful treatment option for DGE after gastrectomy.

This study showed the efficacy of SEMS insertion for DGE following surgical gastrectomy. Endoscopic stent placement provides prompt relief of obstructive symptoms due to various causes after distal gastrectomy. The stenting procedure itself is a minimally invasive therapeutic alternative, which can be performed via simple fluoroscopy-guided endoscopy. After stent insertion, patients did not require prolonged fasting or hospitalization, the quality of life of the patients improved, and adverse events did not occur. Physicians could consider stent placement in patients with postoperative DGE, especially, when rapid oral diet resumption could be helpful for patients.

Endoscopic stent placement, which is minimal invasive procedure, resulted in a high technical success rate and rapid symptom improvement in patients with postoperative DGE. In future research, direct comparison of clinical efficacy between stent placement and other therapeutic method could be helpful for physicians.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Dumitraşcu T, Zhang XF S- Editor: Ma RY L- Editor: A E- Editor: Yin SY

| 1. | International Agency for Research on Cancer. World Cancer Report 2014. Stewart BW, Wild CP, editor. World Health Organization, 2014. . |

| 2. | Hyung WJ, Kim SS, Choi WH, Cheong JH, Choi SH, Kim CB, Noh SH. Changes in treatment outcomes of gastric cancer surgery over 45 years at a single institution. Yonsei Med J. 2008;49:409-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Park JY, von Karsa L, Herrero R. Prevention strategies for gastric cancer: a global perspective. Clin Endosc. 2014;47:478-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Choi KS, Suh M. Screening for gastric cancer: the usefulness of endoscopy. Clin Endosc. 2014;47:490-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sun YF, Yang YG. Study for the quality of life following total gastrectomy of gastric carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011;58:669-673. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Ikeguchi M, Kuroda H, Saito H, Tatebe S, Wakatsuki T. A new pouch reconstruction method after total gastrectomy (pouch-double tract method) improved the postoperative quality of life of patients with gastric cancer. Langenbeck Arch Surg. 2011;396:777-781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kim YW, Baik YH, Yun YH, Nam BH, Kim DH, Choi IJ, Bae JM. Improved quality of life outcomes after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer results of a prospective randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2008;248:721-727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 475] [Cited by in RCA: 505] [Article Influence: 29.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Choi HS, Chun HJ. Accessory Devices Frequently Used for Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection. Clin Endosc. 2017;50:224-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bang CS, Park JM, Baik GH, Park JJ, Joo MK, Jang JY, Jeon SW, Choi SC, Sung JK, Cho KB. Therapeutic Outcomes of Endoscopic Resection of Early Gastric Cancer with Undifferentiated-Type Histology: A Korean ESD Registry Database Analysis. Clin Endosc. 2017;50:569-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hulmemoir I. Role of altered gastric-emptying in the initiation of clinical dumping. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1979;14:463-467. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Fujiwara Y, Nakagawa K, Tanaka T, Utsunomiya J. Relationship between gastroesophageal reflux and gastric emptying after distal gastrectomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:75-79. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Cohen AM, Ottinger LW. Delayed gastric-emptying following gastrectomy. Ann Surg. 1976;184:689-696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jordon GL Jr, Walker LL. Severe problems with gastric emptying after gastric surgery. Ann Surg. 1973;177:660-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bar-Natan M, Larson GM, Stephens G, Massey T. Delayed gastric emptying after gastric surgery. Am J Surg. 1996;172:24-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Behrns KE, Sarr MG. Diagnosis and management of gastric emptying disorders. Adv Surg. 1994;27:233-255. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Chang J, Sharma G, Boules M, Brethauer S, Rodriguez J, Kroh MD. Endoscopic stents in the management of anastomotic complications after foregut surgery: new applications and techniques. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:1373-1381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bège T, Emungania O, Vitton V, Ah-Soune P, Nocca D, Noël P, Bradjanian S, Berdah SV, Brunet C, Grimaud JC. An endoscopic strategy for management of anastomotic complications from bariatric surgery: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:238-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kim SH, Chun HJ, Yoo IK, Lee JM, Nam SJ, Choi HS, Kim ES, Keum B, Seo YS, Jeen YT. Predictors of the patency of self-expandable metallic stents in malignant gastroduodenal obstruction. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:9134-9141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 19. | Kurahara H, Shinchi H, Maemura K, Mataki Y, Iino S, Sakoda M, Ueno S, Takao S, Natsugoe S. Delayed gastric emptying after pancreatoduodenectomy. J Surg Res. 2011;171:e187-e192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wente MN, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, Izbicki JR, Neoptolemos JP, Padbury RT, Sarr MG, Traverso LW. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after pancreatic surgery: a suggested definition by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery. 2007;142:761-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1771] [Cited by in RCA: 2327] [Article Influence: 129.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3). Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:113-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1723] [Cited by in RCA: 1896] [Article Influence: 135.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2014 (ver. 4). Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:1-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1575] [Cited by in RCA: 1914] [Article Influence: 239.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Kim CG, Choi IJ, Lee JY, Cho SJ, Park SR, Lee JH, Ryu KW, Kim YW, Park YI. Covered versus uncovered self-expandable metallic stents for palliation of malignant pyloric obstruction in gastric cancer patients: a randomized, prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:25-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |