Published online Oct 21, 2018. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i39.4489

Peer-review started: July 25, 2018

First decision: August 27, 2018

Revised: August 29, 2018

Accepted: October 5, 2018

Article in press: October 5, 2018

Published online: October 21, 2018

Processing time: 85 Days and 2.9 Hours

To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of combined ursodeoxycholic acid and percutaneous transhepatic balloon dilation for management of gallstones after expulsion of common bile duct (CBD) stones.

From April 2014 to May 2016, 15 consecutive patients (6 men and 9 women) aged 45-86 (mean, 69.07 ± 9.91) years suffering from CBD stones associated with gallstones were evaluated. Good gallbladder contraction function was confirmed by type B ultrasonography. Dilation of the CBD and cystic duct was detected. Percutaneous transhepatic balloon dilation of the papilla was performed, ursodeoxycholic acid was administered, and all patients had a high-fat diet. All subjects underwent repeated cholangiography, and percutaneous transhepatic removal was carried out in patients with secondary CBD stones originating from the gallbladder.

All patients underwent percutaneous transhepatic balloon dilation with a primary success rate of 100%. The combined therapy was successful in 86.7% of patients with concomitant CBD stones and gallstones. No remaining stones were detected in the gallbladder. Transient adverse events include abdominal pain (n = 1), abdominal distension (n = 1), and fever (n = 1). Complications were treated successfully via nonsurgical management without long-term complications. No procedure-related mortality occurred.

For patients with concomitant CBD stones and gallstones, after percutaneous transhepatic removal of primary CBD stones, oral ursodeoxycholic acid and a high-fat diet followed by percutaneous transhepatic removal of secondary CBD stones appear to be a feasible and effective option for management of gallstones.

Core tip: Percutaneous transhepatic removal combined with oral ursodeoxycholic acid and a high-fat diet appears to be a feasible and safe alternative to surgery or endoscopic procedure for elimination of gallstones, especially for patients with good gallbladder contraction function, diameter of gallstones no greater than 12 mm, and dilation of the cystic duct. It also provides an alternative when operative management is not available for patients in poor condition.

- Citation: Chang HY, Wang CJ, Liu B, Wang YZ, Wang WJ, Wang W, Li D, Li YL. Ursodeoxycholic acid combined with percutaneous transhepatic balloon dilation for management of gallstones after elimination of common bile duct stones. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(39): 4489-4498

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v24/i39/4489.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i39.4489

Bile duct stones are the major cause of benign biliary diseases[1]. Surgical exploration or endoscopic intervention can be managed successfully in most common bile duct (CBD) stones[2]. However, open surgery is contraindicated in cases with severe comorbidities, and endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) for extraction of CBD stones in patients with prior surgically modified gastrointestinal tract may result in failure due to invisibility of the papilla of Vater[3]. Hence, percutaneous transhepatic intervention appears to be an alternative for these patients. To prevent the recurrence of CBD stones for patients with concomitant CBD stones and gallstones, subsequent cholecystectomy is the first choice after the elimination of CBD stones within 48 h[4]. Herein, we present our experience in percutaneous transhepatic removal of stones for patients with CBD stones associated with gallstones via an innovative nonsurgical treatment including percutaneous transhepatic balloon dilation (PTBD) combined with oral ursodeoxycholic acid. Moreover, this study aimed to assess the efficacy and safety of this combined therapy.

This was a retrospective study to assess the efficacy and safety of PTBD combined with ursodeoxycholic acid for removal of CBD stones associated with gallstones. The procedure was approved by the ethics committee of our institution. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Fifteen consecutive patients (6 men and 9 women) aged 45-86 (mean, 69.07 ± 9.91) years, diagnosed with concomitant CBD stones and gallstones, admitted to our institution from April 2014 to May 2016 were evaluated.

Overall, 2-5 CBD stones and gallstones were detected in 15 patients, with diameters ranging from 2 to 25 mm. Eleven patients were confirmed to have concomitant CBD stones and gallstones before procedure using type B ultrasonography, enhanced computed tomography, or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), and the remaining 4 were detected by cholangiography during the removal of CBD stones. All patients suffered from fever, jaundice, abdominal discomfort, poor appetite, or vomiting.

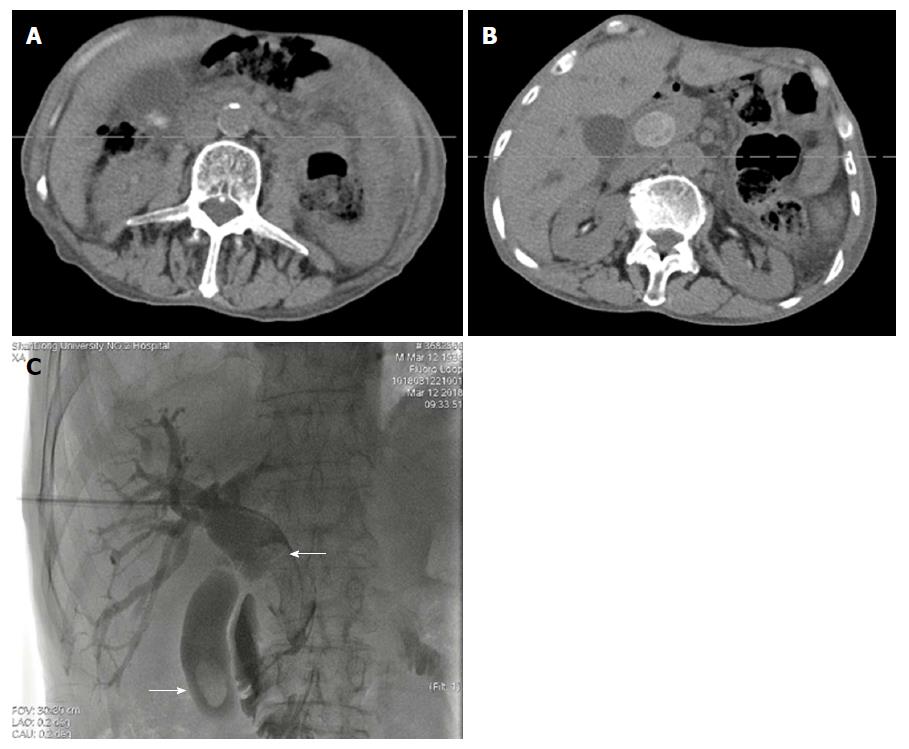

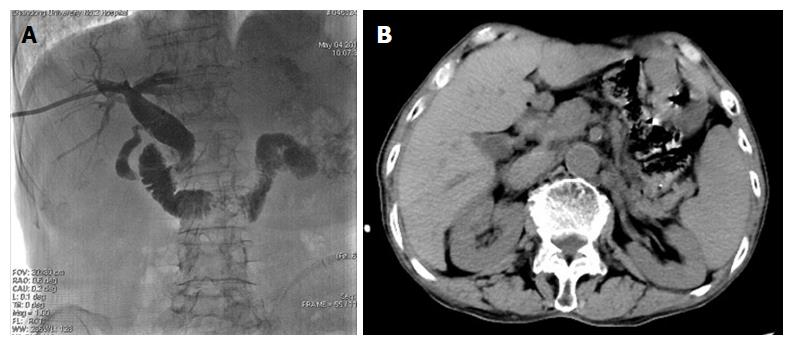

Ultrasonography, enhanced CT, MRCP, or cholangiography were carried out to determine the diagnosis of stones (Figure 1A and B). Pancreatitis was not detected. For patients with poor condition, multiple disciplinary consultations were carried out as pre-procedure assessment.

Follow-up of patients included clinical assessment, physical examination, laboratory test and imaging evaluation for 1 year at a 3-mo interval. Technical success was defined as complete absence of CBD stones. The absence of symptoms was regarded as medical success regardless of the presence or absence of residual stones.

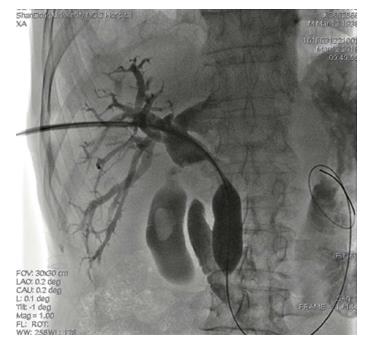

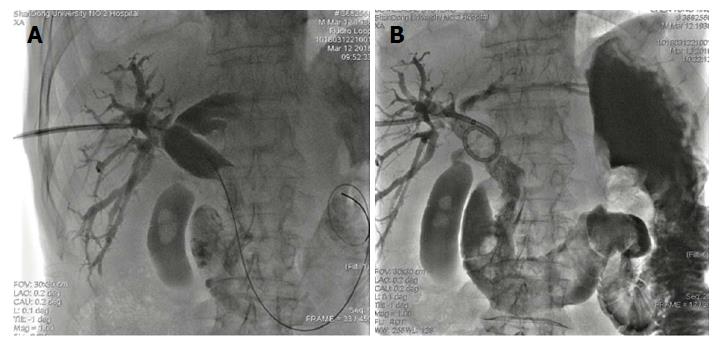

After pretreatment with antibiotics (levofloxacin or cephalosporin), all patients were positioned under intravenous sedation and fluoroscopic monitoring, and a 21G Chiba needle (Neff Percutaneous Access Set, Cook Medical LLC, Bloomington, IN, United States) was used to puncture the right hepatic duct. The biliary tree was shown by injecting a contrast agent via the needle. A tiny guidewire (Wire Guide Diameter inch. 018, Cook Medical LLC, Bloomington, IN, United States) was introduced into the biliary system, and a sheath was inserted into the bile duct over the tiny guidewire. Advancing cholangiography was performed to detect the number, size, and location of stones (Figure 1C). A hydrophilic guidewire [150 cm in length, Terumo (China) Holding Co., Ltd. China] was deployed in the CBD via the transhepatic route. A 6F to 10F sheath [Terumo (China) Holding Co., Ltd. China] was introduced into the right hepatic duct according to the balloon size to dilate the papilla of Vater. A Vert catheter (Cook Medical LLC, Bloomington, IN, United States) was introduced into the duodenum or jejunum. A stiff guidewire [260 cm in length, Terumo (China) Holding Co., Ltd. China] was passed through the catheter and papilla of Vater. An angiographic catheter balloon was inserted through the stiff guidewire and was placed across the papilla. The diameter of the balloon varied from 12 mm to 24 mm and its length was 40 mm or 60 mm depending on the size of the stones (Figure 2). The papilla was inflated gradually until the maximal pressure reached 6-8 atm. Stone-crushing device such as a basket was used in some cases with large stones. Larger balloon was inserted to dilate the papilla in patients with primary failure, and stone expulsion was performed repeatedly. Intraoperative cholangiography was performed to confirm residual stones in CBD. An 8.5F external drainage tube (Biliary Drainage Catheter, Cook Medical LLC, Bloomington, IN, United States) was deployed in the CBD for postoperative drainage and assessment of efficacy of the procedure (Figure 3).

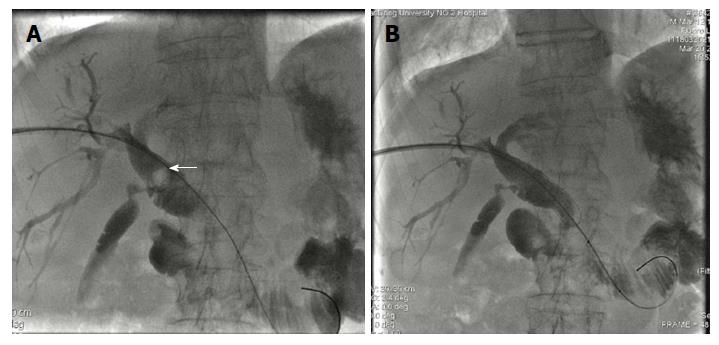

Oral ursodeoxycholic acid (250 mg, Losan Pharma GmbH) was initiated in all patients after procedure. The prescribed dose was 250 mg three times a day. After 7-10 d, repeated cholangiography via external drainage catheter was performed, and balloon dilation of the sphincter of Oddi and elimination of stones were carried out in patients with secondary CBD stones (Figures 4 and 5). Intraoperative cholangiography confirmed the absence of all stones and the external drainage tube was left (Figure 6A). Furthermore, 3-5 d after the procedure, cholangiography was performed again to confirm no residual of stones, and the catheter was retrieved (Figure 6B).

Data are reported as mean ± standard deviation. Comparison of means was analyzed by the paired t-test. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 24.0. P-values < 0.05 were defined as statistical difference for all data.

Table 1 shows baseline characteristics of the patients. Table 2 shows that complete clearance of CBD stones was obtained in one session for all patients. No plastic or bare mental stent was inserted in any patients. All patients were administered subsequently with oral ursodeoxycholic acid after undergoing PTBD. Secondary CBD stones originating in the gallbladder were detected in 13 of these patients with concomitant CBD stones and gallstones. The stones were eliminated in one session in all these patients. Gallstones with reduced size still existed in situ in the remaining two patients. One patient with residual gallstones with symptoms was transferred to department of general surgery for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. One asymptomatic patient was discharged. Intensive long-term follow-up was essential for them. No further treatment except for observation was carried out for this patient. No evidence of retained CBD stones was detected in any patients. The technical success rate was 86.7%, and the overall medical successful rate was 93.3%.

| No. | Gender /age | CBD/gallbladder | ||

| Number of stones | Diameter of the largest stone (mm) | Diameter of the largest balloon (mm) | ||

| 1 | F/58 | 2/2 | 10/6 | 12/8 |

| 2 | M/45 | 3/1 | 15/7 | 16/8 |

| 3 | M/75 | 1/2 | 25/10 | 24/10 |

| 4 | F/67 | 1/1 | 20/8 | 20/8 |

| 5 | F/64 | 3/2 | 20/9 | 20/10 |

| 6 | M/68 | 2/2 | 21/10 | 20/10 |

| 7 | F/73 | 3/1 | 22/14 | 20/- |

| 8 | F/76 | 3/2 | 20/11 | 20/12 |

| 9 | M/86 | 2/1 | 21/10 | 20/10 |

| 10 | F/81 | 3/1 | 19/8 | 18/8 |

| 11 | F/67 | 1/2 | 20/10 | 20/10 |

| 12 | F/72 | 2/1 | 21/12 | 20/12 |

| 13 | M/76 | 2/3 | 18/15 | 18/- |

| 14 | F/65 | 3/1 | 18/12 | 18/12 |

| 15 | M/63 | 1/1 | 20/12 | 20/12 |

| No. | Primary technical success | Secondary technical success | Adverse events | Treatment |

| 1 | Yes | Yes | No | |

| 2 | Yes | Yes | Fever | Medication |

| 3 | Yes | Yes | No | |

| 4 | Yes | Yes | No | |

| 5 | Yes | Yes | Abdominal distension | Medication |

| 6 | Yes | Yes | No | |

| 7 | Yes | No | No | |

| 8 | Yes | Yes | No | |

| 9 | Yes | Yes | No | |

| 10 | Yes | Yes | No | |

| 11 | Yes | Yes | Abdominal pain | Medication |

| 12 | Yes | Yes | No | |

| 13 | Yes | No | No | |

| 14 | Yes | Yes | No | |

| 15 | Yes | Yes | No |

Table 3 demonstrates the result of laboratory tests pre and postintervention. Serum alanine transaminase and total bilirubin (TBIL) levels became normal in patients with jaundice after the procedure. White blood cell (WBC) levels decreased significantly on day 14 postoperatively. However, there was no statistical difference between preoperative and postoperative values for hemoglobin and amylase.

| Pre-intervention | 2 wk after intervention | t | P value | |

| ALT (U/L) | 98.93 ± 24.47 | 36.13 ± 8.99 | 10.41 | < 0.001 |

| TBIL (μmol/L) | 39.40 ± 7.76 | 21.47 ± 12.09 | 6.52 | < 0.001 |

| Amylase (U/L) | 80.73 ± 14.94 | 82.07 ± 17.77 | 0.34 | 0.741 |

| WBC (× 109/L) | 11.58 ± 1.45 | 7.65 ± 2.11 | 5.90 | < 0.001 |

| HGB (g/L) | 122.93 ± 8.66 | 118.80 ± 13.39 | 1.52 | 0.150 |

Transient adverse effects including vomiting, chills, fever, and abdominal distension were found in a few patients after the procedure. They were cured with analgesic and antiemetic argents. No severe complications such as bile peritonitis, hemobilia, and cholangitis occurred. TBIL and WBC values of one patient complicated with fever were 63 μmol/L and 12.21 × 109/L, respectively, after the procedure. One patient suffered from abdominal distention and decreased hemoglobin levels from 122 g/L to 82 g/L. The WBC count increased slightly for the patient complicated with abdominal pain. All complications were treated successfully via nonsurgical management without remote complications. Antibiotics (Ceftriaxone) and somatostatin were injected until the symptoms vanished. No procedure-related mortality occurred. During 1-year follow-up, no obstruction of bile ducts or recurrence of symptoms was detected.

Bile duct stones, one of the most common digestive problems needing admission to hospital, are the major cause of benign diseases of the biliary tract, such as obstructive jaundice and cholangitis[1,5]. It includes intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile duct stones, CBD stones and gallstones. CBD stones comprise primary and secondary stones. Secondary stones from the gallbladder and migrating into the ductal system are different from primary stones that form in the biliary tract. Primary stones may be the consequence of bacterial infection and biliary stasis. The majority of the secondary stones are cholesterol gallstones, while primary stones are mainly pigment stones[6]. Compared to the Western population, primary stones are more prevalent in Asia[7]. The prevalence of CBD stones in patients with symptomatic gallstones varies from 10% to 20%[8]. In this study, 15 patients with CBD stones suffered from gallstones, of which 11 were confirmed before the procedure, while 4 patients who underwent PTBD had gallstones detected by cholangiography.

Many people are hospitalized for acute pancreatitis due to CBD stones that occlude the ampulla. In addition, bile duct obstruction caused by stones result in septic cholangitis. Chronic occlusion could induce secondary biliary cirrhosis. All types of CBD stones should be cured aggressively. Many management options, including open surgery, laparoscopic surgery, endoscopic and percutaneous procedure, are available for removal of CBD stones[1,2,9-11]. Abdominal exploration with incision of the CBD and stone removal was the predominant choice a few decades ago. With technological advances and improvement of skills, various alternatives could be employed in the extraction of bile duct stones. However, open surgery still retains its important role in the management of complicated stone disease. Laparoscopic procedure has comparable morbidity and mortality rates to open surgery. Hence, both open and laparoscopic surgery should be considered in cases unsuitable to be treated by nonsurgical options.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was first introduced in 1968[12]. It was accepted quickly as a feasible diagnostic and therapeutic technique for CBD stones[13,14]. In the 1990s, EST was considered a feasible alternative for patients with serious comorbidity contraindicated to open surgery[15,16]. It appears to be a better choice for elder patients with benign biliary tract diseases. CBD stones could be eliminated by ERCP via sphincterotomy or balloon dilation[17]. For patients requiring maintenance of papillary function, balloon dilation may be an effective and safe alternative to EST in the management of bile duct stones[18-20]. However, open surgery is superior to ERCP for clearance of CBD stones. Compared to open surgery, ERCP necessitates increased number of procedures for each patient[2]. Complications of ERCP with sphincterotomy include hemorrhage, papillary stenosis, pancreatitis, duodenal perforation, and recurrent stones[21], and the complication rate ranges from 0.5%-5.4%[22].

In the past decades, percutaneous intervention has been reported as an effective alternative to open or laparoscopic surgery and endoscopic intervention for elimination of CBD stones[9,23,24]. Several reports indicated that transhepatic balloon dilation of papilla could be an alternative to extraction of biliary stones[23-25]. Numerous devices, such as Dormia basket, occlusive, or cutting balloon, were introduced to improve the success rate of the technique[25-27]. The technique success rate varies from 94.7% to 100%[28,29]. Papillary dilation was performed using balloons with a diameter ranging from 8 mm to 20 mm[9,28,30]. Transient adverse events, including nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain, were observed in some cases which resolved with medication composed with analgesic and antiemetic drugs. A study by Nevzat Ozcan revealed 18 complications, including cholangitis (2.7%), subcapsular biloma (1.5%), subcapsular hemotoma (0.38%), subcapsular abscess (0.38%), bile peritonitis (0.38%), duodenal perforation (0.38%), and CBD perforation (0.38%)[9]. Only 2 of 38 main complications were observed by Santiago Gil with complete expulsion of stones in 36 of the 38 patients. No procedure-related deaths occurred[29]. Although a few cases were reported, ERCP for patients with prior Billroth II gastrectomy may be challenging[26,31,32]. EST for extraction of CBD stones may lead to failure, even in experienced surgeons[33]. For these cases, percutaneous transhepatic intervention appears to be an available and safe management for expulsion of stones[34].

Several other methods for percutaneous expulsion of stones to the duodenum were reported. Extraction from the T-tube or existing gallbladder drain for access has been published as an effective percutaneous technique for stone expulsion[30,35]. A novel technique of combined percutaneous transhepatic and endoscopic or laparoscopic approach also acts an important role in patients unsuitable to be treated with routine ERCP[36-38].

Gallstones with a higher prevalence in adults may occur in all societies and races. Its increasing prevalence associates with age in both sexes, and women are involved more commonly than men[6]. Gallstones are composed of cholesterol, calcium bilirubinate, protein, lipid, and less water. Occlusion of the gallbladder duct can cause abdominal pain, chills, fever, and jaundice. Treatment is indicated in patients with symptomatic gallstones. Cholecystectomy is the most effective procedure for symptomatic patients[39]. Laparoscopic, small-incision, or open cholecystectomy could be a feasible treatment in the management of gallstones. These three techniques can resolve symptoms caused by gallstones. No statistically significant differences in the outcome have been found. Although laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the most popular method, small-incision cholecystectomy has shorter operative time and appears to be less costly[40]. However, the increased incidence of colon cancer is associated with cholecystectomy[41]. Several nonsurgical treatments have been developed for treatment of gallstones with recurrence. Percutaneous cholecytostomy serves a role with few complications in management acute calculous cholecystitis[42,43]. Medical treatment also plays an important role in management of gallstones. Gallstone dissolution may be achieved by oral administration of ursodeoxycholic acid which decreases biliary cholesterol secretion, increases solubility of cholesterol by formation of liquid crystals, and reduces intestinal cholesterol absorption[39].

To prevent the recurrence of stones, for CBD stones associated with gallstones, subsequent cholecystectomy is the first choice after the elimination of the CBD stones within 48 h[4]. Patients with suspected or proven CBD stones undergoing cholecystectomy can anticipate benefit from the perioperative management of CBD stones[11]. Nowadays, several procedures depending on the experience of surgeons are available for treatment of combined cholecystocholedocholithiasis, such as laparoscopic treatment, simultaneous laparoendoscopic treatment, and combined ERCP and EST with cholecystectomy[44]. Concurrent transhepatic percutaneous balloon dilation combined with laparoscopic cholecystectomy is introduced for treatment of gallstones associated with CBD stones[38]. Fifteen patients with concomitant CBD stones and gallstones were enrolled in our study, and the primary technical success rate was 100%. Subsequently, PTBD was performed repeatedly to expel secondary CBD stones originating in the gallbladder. Immediate complications including bile peritonitis, bile pleura effusion, hemobilia, acute pancreatitis, and duodenum perforation, were not observed in our study. All slight complications were treated successfully via nonsurgical management.

In our series, 15 patients with CBD stones and gallstones were enrolled and 13 of them were treated successfully via an innovative technique. For these patients, the strategy of treatment was as follows: First, routine PTBD was performed to eliminate the CBD stones without any difficulties. Then, all patients with good gallbladder contraction function were confirmed. Second, ursodeoxycholic acid, a kind of oral dissolution agent, was administered to patients with 250 mg for three times per day. A high-fat diet was initiated similar to that in gallbladder contraction test. Third, repeated cholangiography was performed 7-10 d later, and 13 cases showed secondary CBD stones originating in the gallbladder retaining in the CBD. Gallstones with reduced size still existed in situ in the remaining two patients. For patients with secondary CBD stones, subsequently PTBD was carried out repeatedly with great care, and the stones were expulsed into the duodenum. One asymptomatic patient with reduced gallstones was discharged directly with intending long-term follow-up. The remaining patient underwent cholecystectomy. Three to five days later, cholangiography demonstrated no residual stones in all patients with secondary CBD stones, and the drainage tubes were removed.

In conclusion, PTBD is an option for patients with CBD stones. Percutaneous transhepatic removal combined with oral ursodeoxycholic acid and a high-fat diet appears to be a feasible and safe alternative to surgery or endoscopic procedure for elimination of gallstones, especially for patients with good gallbladder contraction function, diameter of gallstones no greater than 12 mm, and dilation of the cystic duct. It also provides an alternative when operative management is not available for patients in poor condition.

Bile duct stones are the most frequent cause of benign bile duct disease. The choice of management of common bile duct (CBD) stones includes surgical exploration, endoscopic intervention and percutaneous transhepatic intervention. Subsequent cholecystectomy is the first choice to prevent the recurrence of stones for patients with concomitant CBD stones and gallstones. This retrospective study aimed to evaluate the clinical efficacy and safety of ursodeoxycholic acid combined with percutaneous transhepatic balloon dilation for management of gallstones after elimination of CBD Stones.

Percutaneous transhepatic intervention served as an effective option for management of CBD stones in the past decades. The preferable choice of management for patients with concomitant CBD stones and gallstones is controversial.

The retrospective study evaluated the effectiveness and safety of a novel technique for management of gallstones after expulsion of CBD stones in terms of technical success and postoperative complications.

Fifteen consecutive patients diagnosed with concomitant CBD stones and gallstones were evaluated. All patients underwent application of ursodeoxycholic acid combined with percutaneous transhepatic balloon dilation for management of gallstones after elimination of CBD stones. Clinical assessment, physical examination, laboratory tests and imaging were assessed in all patients. All statistics analyses were performed using SPSS 24.0. P-values < 0.05 were defined as statistically difference for all data.

The novel technique was successful in 86.7% of patients with concomitant CBD stones and gallstones with few postoperative complications treated successfully via nonsurgical management. It seems to be an alternative to open or laparoscopic surgery and endoscopic intervention.

The present study showed that ursodeoxycholic acid combined with percutaneous transhepatic balloon dilation was secure and feasible for management of gallstones after elimination of CBD stones, especially for patients with good gallbladder contraction function, diameter of gallstone no greater than 12 mm, and dilation of the cystic duct. It also provides an alternative when operative management is not available for patients in poor condition.

In case of therapeutic failure, good gallbladder contraction function or dilation of the cystic duct was not observed. However, the diameters of stones in failed cases were much greater than those of successful cases. This novel technique provides a feasible option for patients with concomitant gallstones and CBD stones. Prospective studies are needed for further confirmation.

The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Yuan Zhang from Center of Evidence-based Medicine, Second Hospital of Shandong University.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Kazuya S, Morling JR, Schievenbusch S S- Editor: Wang XJ L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Huang Y

| 1. | Buxbaum J. Modern management of common bile duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2013;23:251-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Dasari BV, Tan CJ, Gurusamy KS, Martin DJ, Kirk G, McKie L, Diamond T, Taylor MA. Surgical versus endoscopic treatment of bile duct stones. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;CD003327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ross AS. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in the surgically modified gastrointestinal tract. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2009;19:497-507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL). EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of gallstones. J Hepatol. 2016;65:146-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 444] [Cited by in RCA: 348] [Article Influence: 38.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 5. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Chathadi KV, Chandrasekhara V, Acosta RD, Decker GA, Early DS, Eloubeidi MA, Evans JA, Faulx AL, Fanelli RD, Fisher DA, Foley K, Fonkalsrud L, Hwang JH, Jue TL, Khashab MA, Lightdale JR, Muthusamy VR, Pasha SF, Saltzman JR, Sharaf R, Shaukat A, Shergill AK, Wang A, Cash BD, DeWitt JM. The role of ERCP in benign diseases of the biliary tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:795-803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Portincasa P, Moschetta A, Palasciano G. Cholesterol gallstone disease. Lancet. 2006;368:230-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 554] [Cited by in RCA: 490] [Article Influence: 25.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 7. | Williams EJ, Green J, Beckingham I, Parks R, Martin D, Lombard M; British Society of Gastroenterology. Guidelines on the management of common bile duct stones (CBDS). Gut. 2008;57:1004-1021. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 361] [Cited by in RCA: 353] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Frossard JL, Morel PM. Detection and management of bile duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:808-816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ozcan N, Kahriman G, Mavili E. Percutaneous transhepatic removal of bile duct stones: results of 261 patients. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2012;35:621-627. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ponsky JL. Laparoscopic therapy of cholelithiasis. Annu Rev Med. 1993;44:317-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Graham SM, Flowers JL, Scott TR, Bailey RW, Scovill WA, Zucker KA, Imbembo AL. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy and common bile duct stones. The utility of planned perioperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiography and sphincterotomy: experience with 63 patients. Ann Surg. 1993;218:61-67. [PubMed] |

| 12. | McCune WS, Shorb PE, Moscovitz H. Endoscopic cannulation of the ampulla of vater: a preliminary report. Ann Surg. 1968;167:752-756. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Law R, Baron TH. ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:428-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Moon JH, Choi HJ, Lee YN. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Endoscopy. 2014;46:775-778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tham TC, Carr-Locke DL, Collins JS. Endoscopic sphincterotomy in the young patient: is there cause for concern? Gut. 1997;40:697-700. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Wojtun S, Gil J, Gietka W, Gil M. Endoscopic sphincterotomy for choledocholithiasis: a prospective single-center study on the short-term and long-term treatment results in 483 patients. Endoscopy. 1997;29:258-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Minami A, Nakatsu T, Uchida N, Hirabayashi S, Fukuma H, Morshed SA, Nishioka M. Papillary dilation vs sphincterotomy in endoscopic removal of bile duct stones. A randomized trial with manometric function. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:2550-2554. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Yasuda I, Tomita E, Enya M, Kato T, Moriwaki H. Can endoscopic papillary balloon dilation really preserve sphincter of Oddi function? Gut. 2001;49:686-691. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Bergman JJ, van Berkel AM, Bruno MJ, Fockens P, Rauws EA, Tijssen JG, Tytgat GN, Huibregtse K. A randomized trial of endoscopic balloon dilation and endoscopic sphincterotomy for removal of bile duct stones in patients with a prior Billroth II gastrectomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:19-26. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Liao WC, Tu YK, Wu MS, Wang HP, Lin JT, Leung JW, Chien KL. Balloon dilation with adequate duration is safer than sphincterotomy for extracting bile duct stones: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1101-1109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Tse F, Yuan Y. Early routine endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography strategy versus early conservative management strategy in acute gallstone pancreatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;CD009779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, Moore JP, Fennerty MB, Ryan ME, Shaw MJ. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1716] [Cited by in RCA: 1689] [Article Influence: 58.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 23. | Perez MR, Oleaga JA, Freiman DB, McLean GL, Ring EJ. Removal of a distal common bile duct stone through percutaneous transhepatic catheterization. Arch Surg. 1979;114:107-109. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Haskin PH, Teplick SK, Gambescia RA, Zitomer N, Pavlides CA. Percutaneous transhepatic removal of a common bile duct stone after mono-octanoin infusion. Radiology. 1984;151:247-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Clouse ME. Dormia basket modification for percutaneous transhepatic common bile duct stone removal. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1983;140:395-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Itoi T, Ishii K, Itokawa F, Kurihara T, Sofuni A. Large balloon papillary dilation for removal of bile duct stones in patients who have undergone a billroth ii gastrectomy. Dig Endosc. 2010;22 Suppl 1:S98-S102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Oguzkurt L, Ozkan U, Gumus B. Percutaneous transhepatic cutting balloon papillotomy for removal of common bile duct stones. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2009;32:1117-1119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Han JY, Jeong S, Lee DH. Percutaneous papillary large balloon dilation during percutaneous cholangioscopic lithotripsy for the treatment of large bile-duct stones: a feasibility study. J Korean Med Sci. 2015;30:278-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Gil S, de la Iglesia P, Verdú JF, de España F, Arenas J, Irurzun J. Effectiveness and safety of balloon dilation of the papilla and the use of an occlusion balloon for clearance of bile duct calculi. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174:1455-1460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Atar E, Neiman C, Ram E, Almog M, Gadiel I, Belenky A. Percutaneous trans-papillary elimination of common bile duct stones using an existing gallbladder drain for access. Isr Med Assoc J. 2012;14:354-358. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Dolay K, Soylu A. Easy sphincterotomy in patients with Billroth II gastrectomy: a new technique. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2008;19:109-113. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Kim KH, Kim TN. Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation for the retrieval of bile duct stones after prior Billroth II gastrectomy. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:128-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Arnold JC, Benz C, Martin WR, Adamek HE, Riemann JF. Endoscopic papillary balloon dilation vs. sphincterotomy for removal of common bile duct stones: a prospective randomized pilot study. Endoscopy. 2001;33:563-567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Shirai N, Hanai H, Kajimura M, Kataoka H, Yoshida K, Nakagawara M, Nemoto M, Nagasawa M, Kaneko E. Successful treatment of percutaneous transhepatic papillary dilation in patients with obstructive jaundice due to common bile duct stones after Billroth II gastrectomy: report of two emergent cases. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;30:91-93. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Baban C, Rajendran S, O’Hanlon D, Murphy M. Utilisation of cholecystostomy and cystic duct as a route for percutaneous cutting balloon papillotomy and expulsion of common bile duct stones. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Itoi T, Shinohara Y, Takeda K, Nakamura K, Sofuni A, Itokawa F, Moriyasu F, Tsuchida A. A novel technique for endoscopic sphincterotomy when using a percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscope in patients with an endoscopically inaccessible papilla. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:708-711. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Matsumoto S, Ikeda S, Maeshiro K, Okamoto K, Miyazaki R. Management of giant common bile duct stones in high-risk patients using a combined transhepatic and endoscopic approach. Am J Surg. 1997;173:115-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Li S, Li Y, Geng J, Liu B, Gao R, Zhou Z, Hu S. Concurrent Percutaneous Transhepatic Papillary Balloon Dilatation Combined with Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy for the Treatment of Gallstones with Common Bile Duct Stones. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2015;25:886-891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Lammert F, Miquel JF. Gallstone disease: from genes to evidence-based therapy. J Hepatol. 2008;48 Suppl 1:S124-S135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Keus F, Gooszen HG, van Laarhoven CJ. Open, small-incision, or laparoscopic cholecystectomy for patients with symptomatic cholecystolithiasis. An overview of Cochrane Hepato-Biliary Group reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;CD008318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Shao T, Yang YX. Cholecystectomy and the risk of colorectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1813-1820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Bortoff GA, Chen MY, Ott DJ, Wolfman NT, Routh WD. Gallbladder stones: imaging and intervention. Radiographics. 2000;20:751-766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Gurusamy KS, Rossi M, Davidson BR. Percutaneous cholecystostomy for high-risk surgical patients with acute calculous cholecystitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;CD007088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | La Greca G, Barbagallo F, Sofia M, Latteri S, Russello D. Simultaneous laparoendoscopic rendezvous for the treatment of cholecystocholedocholithiasis. Surg Endosc. 2009;24:769-780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |