Published online Sep 21, 2018. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i35.4028

Peer-review started: June 8, 2018

First decision: July 3, 2018

Revised: July 12, 2018

Accepted: July 22, 2018

Article in press: July 22, 2018

Published online: September 21, 2018

Processing time: 103 Days and 17.4 Hours

To investigate whether the adipocytes derived hormone adiponectin (ADPN) affects the mechanical responses in strips from the mouse gastric fundus.

For functional experiments, gastric strips from the fundal region were cut in the direction of the longitudinal muscle layer and placed in organ baths containing Krebs-Henseleit solution. Mechanical responses were recorded via force-displacement transducers, which were coupled to a polygraph for continuous recording of isometric tension. Electrical field stimulation (EFS) was applied via two platinum wire rings through which the preparation was threaded. The effects of ADPN were investigated on the neurally-induced contractile and relaxant responses elicited by EFS. The expression of ADPN receptors, Adipo-R1 and Adipo-R2, was also evaluated by touchdown-PCR analysis.

In the functional experiments, EFS (4-16 Hz) elicited tetrodotoxin (TTX)-sensitive contractile responses. Addition of ADPN to the bath medium caused a reduction in amplitude of the neurally-induced contractile responses (P < 0.05). The effects of ADPN were no longer observed in the presence of the nitric oxide (NO) synthesis inhibitor L-NG-nitro arginine (L-NNA) (P > 0.05). The direct smooth muscle response to methacholine was not influenced by ADPN (P > 0.05). In carbachol precontracted strips and in the presence of guanethidine, EFS induced relaxant responses. Addition of ADPN to the bath medium, other than causing a slight and progressive decay of the basal tension, increased the amplitude of the neurally-induced relaxant responses (P < 0.05). Touchdown-PCR analysis revealed the expression of both Adipo-R1 and Adipo-R2 in the gastric fundus.

The results indicate for the first time that ADPN is able to influence the mechanical responses in strips from the mouse gastric fundus.

Core tip: Evidence exists that some white adipose-tissue derived hormones that are involved in the regulation of food intake also influence the motor responses of the gastrointestinal tract. In this view, adiponectin (ADPN) too has been reported to influence food intake but no data concerning its effects on the gastric mechanical activity are available. The present results indicate for the first time that ADPN is able to influence the mechanical responses in strips from the mouse gastric fundus. It could be speculated that these peripheral effects on motor phenomena might represent an additional mechanism engaged by the hormone to control food intake.

- Citation: Idrizaj E, Garella R, Castellini G, Mohr H, Pellegata NS, Francini F, Ricca V, Squecco R, Baccari MC. Adiponectin affects the mechanical responses in strips from the mouse gastric fundus. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(35): 4028-4035

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v24/i35/4028.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i35.4028

White adipose tissue is recognized as an endocrine organ[1], being able to secrete many substances, known as adipokines, that are involved in a wide range of functions[1,2]. Among them, accumulating evidence suggests that adipose-tissue derived hormones, such as leptin and adiponectin (ADPN), play an important role in the systemic metabolic homeostasis, also acting as key neuromodulators of food intake[1-6]. ADPN is a peptide hormone mainly produced by white adipose tissue although its expression has been reported also in other organs of different animal species[7], including the mouse stomach[8]. ADPN exerts its effects mainly through the activation of two seven transmembrane domain receptors, Adipo-R1 and Adipo-R2[9], whose expression has been revealed, other than in the brain, in a variety of mammalian peripheral tissues[7]. Particularly, Adipo-R2 mRNA expression has been reported in the gastrointestinal tract of rats[10].

Interestingly, many substances that act centrally to modulate food intake also influence the activity of gastrointestinal smooth muscle[11-14], whose motor phenomena represent a source of peripheral signals involved in the control of feeding behavior thought the gut-brain axis[15].

All the above knowledge are consistent with the possibility that ADPN too could affect gastrointestinal motor responses, although no data are present in the literature concerning these effects.

On this ground, in the present study we investigated whether ADPN influences the mechanical responses in strips from the mouse gastric fundus. The expression of both the ADPN receptors was also evaluated by touchdown-PCR analysis.

Experiments were carried out on 8-12 wk old C57BL/6 female mice (Charles River, Lecco, Italy). The animals were fed standard laboratory chow and water, and were housed under a 12-h light/12-h dark (12 L : 12 D) photoperiod and controlled temperature (21 °C± 1 °C). The experimental protocol was designed in compliance with the guidelines of the European Communities Council Directive 2010/63/UE and the recommendations for the care and use of laboratory animals approved by the Animal Care Committee of the University of Florence, Italy, with authorization from the Italian Ministry of Health nr. 787/2016-PR. The mice were killed by prompt cervical dislocation to minimize animal suffering.

As previously published by our research group[16,17], the stomach was rapidly dissected from the abdomen and two full-thickness strips (2 mm × 10 mm) were cut in the direction of the longitudinal muscle layer from each fundal region. One end of each strip was tied to a platinum rod while the other was connected to a force displacement transducer (Grass model FT03) by a silk thread for continuous recording of isometric tension. The transducer was coupled to a polygraph (7K; Grass Instrument). Muscle strips were mounted in 5 mL double-jacketed organ baths containing Krebs-Henseleit solution, which consisted of 118 mmol/L NaCl, 4.7 mmol/L KCl, 1.2 mmol/L MgSO4, 1.2 mmol/L KH2PO4, 25 mmol/L NaHCO3, 2.5 mmol/L CaCl2, and 10 mmol/L glucose pH 7.4, and bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2. Prewarmed water (37 °C) was circulated through the outer jacket of the tissue bath via a constant-temperature circulator pump. The temperature of the Krebs-Henseleit solution in the organ bath was maintained within ± 0.5 °C.

Electrical field stimulation (EFS) was applied via two platinum wire rings (2 mm diameter, 5 mm apart) through which the preparation was threaded. Electrical impulses (rectangular waves, 80 V, 4-16 Hz, 0.5 ms, for 15 s) were provided by a Grass model S8 stimulator. Strips were allowed to equilibrate for 1 h under an initial load of 0.8 g. During this period, repeated and prolonged washes of the preparations with Krebs-Henseleit solution were done to avoid accumulation of metabolites in the organ baths.

The following drugs were used: acetyl-β-methylcholine chloride (methacholine), recombinant full-length mouse adiponectin (ADPN), atropine sulphate, carbachol (CCh), guanethidine sulphate, L-NG-nitro arginine (L-NNA), tetrodotoxin (TTX). All drugs were obtained from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO, United States). Solutions were prepared on the day of the experiment, except for TTX and ADPN, for which stock solutions were kept stored at -20 °C.

Drug concentrations are referred as final bath concentrations. For ADPN we started from 20 pmol/L, i.e., the dose previously reported to be effective in in vitro gastric preparations[8]. Direct smooth muscle contractions were obtained by addition of methacholine to the bath medium. The interval between two subsequent applications of methacholine was no less than 30 min, during which repeated and prolonged washes of the preparations with Krebs-Henseleit solution were performed. In order to investigate the effects of ADPN in non-adrenergic, non-cholinergic (NANC) condition, guanethidine and CCh were added to the bath medium, to rule out the adrenergic and the cholinergic influences, respectively. When contraction elicited by CCh reached a stable plateau phase, EFS or drugs were applied.

Aiming to assess the presence of mRNA for ADPN receptors in gastric fundal tissue, mouse tissues were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C until use.

Then, from frozen tissue sections, RNA was extracted using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed for AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 receptors and the following primers were used:

AdipoR1 forward 5’-CAG AGA AGC TGA CAC AGT GGA G-3’ and reverse 5’-GTC CCT CCC AGA CCT TAT ACA C-3’; AdipoR2 forward 5’-GGA CTC CAG AGC CAG ATA TAC G-3’ and reverse 5’-ACT CTT CCA TTC GTT CCA TAG C-3’.

The mixtures listed in Table 1 were prepared in thin walled 0.2 mL tubes and analysed by Biometra PCR cycler. PCRs were run with the program reported in Table 2.

| Reagents | Volume |

| Forward primer (0.01 pmol/L) | 1 μL |

| Reverse primer (0.01 pmol/L) | 1 μL |

| GOTaq colorless Master Mix sample (PromegaR) | 12.5 μL |

| H2O | 9.5 μL |

| cDNA template | 1 μL |

| Step | Temperature (°C) | Time | Note |

| 1 | 94 | 3 min | - |

| 2 | 94 | 20 s | - |

| 3 | 64 | 30 s | -0.5 °C per cycle |

| 4 | 72 | 35 s | Repeat steps 2-4 for 12 cycles |

| 5 | 94 | 20 s | - |

| 6 | 58 | 30 s | - |

| 7 | 72 | 35 s | Repeat steps 5-7 for 25 cycles |

| 8 | 72 | 2 min | - |

| 9 | 4 | Hold |

Three gastric fundus were evaluated and a negative control without cDNA template as well as a positive control containing cDNA of inguinal fat pad were analyzed in parallel. The positive control was chosen since both Adipo-R1 and Adipo-R2 are well expressed in adipocytes which are the most relevant cell types for these receptors[18].

Amplitude of contractile responses is expressed as percentage of the muscular contraction evoked by 2 μmol/L methacholine, assumed as 100% or as absolute values (g). Amplitude of contractile responses to methacholine was measured 30 s after a stable plateau phase was reached. Relaxant responses are expressed as percentage decrease relative to the muscular tension induced by 1 μmol/L CCh just before obtaining relaxations. Amplitude values of EFS-induced relaxations refer to the maximal peak obtained during the stimulation period.

Statistical analysis was performed by means of Student’s t-test to compare two experimental groups or one-way ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls posttest when more than two groups were compared. Values were considered significantly different with P < 0.05. Results are given as means ± SE. The number of muscle strip preparations is designated by n in the results.

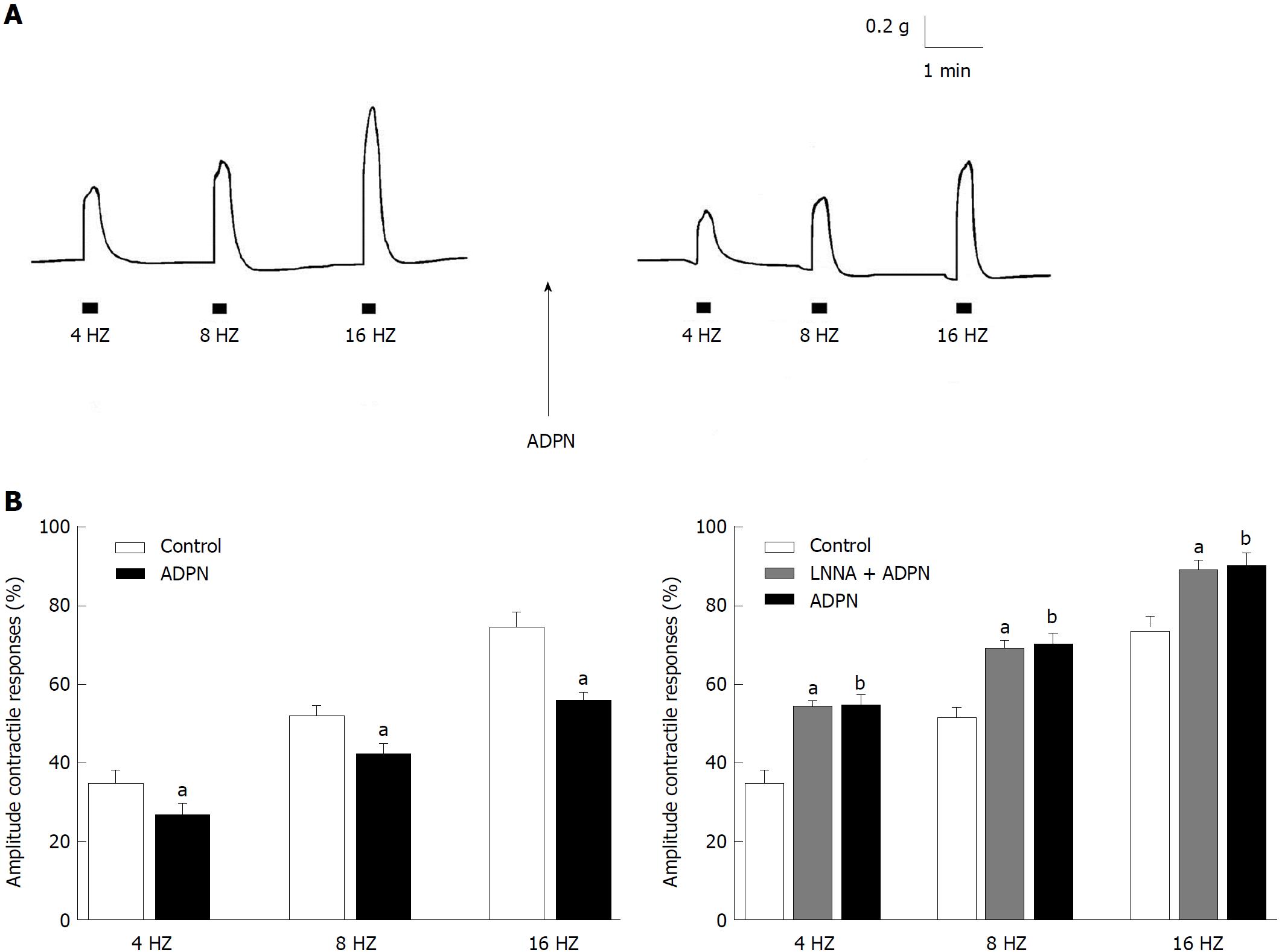

At basal tension EFS (4-16 Hz) induced (n = 22) contractile responses, whose amplitude increased by increasing the stimulation frequency (Figure 1A). As previously observed in the mouse gastric fundus[16,17], the EFS-evoked contractile responses were abolished by TTX (1 μmol/L) (P < 0.05) or atropine (1 μmol/L) (P < 0.05), thus indicating that they were neurally-induced and cholinergic in nature.

Addition of ADPN to the bath medium caused, at 20 nmol/L (n = 12), a statistically significant reduction (P < 0.05) in amplitude of the neurally-induced excitatory responses in the whole range of stimulation frequency employed (Figure 1A and B). The effects of ADPN were already appreciable 10 min after its addition to the bath medium and persisted up to 60 min (longer time not observed). Addition of the nitric oxide (NO) synthesis inhibitor L-NNA (200 μmol/L) to the bath medium (n = 6) caused an increase in amplitude of the EFS-induced contractile responses (Figure 1B). In the presence of L-NNA, the depressant effects of ADPN on the neurally-induced contractile responses were no longer observed (Figure 1B).

Addition of the muscarinic receptors agonist methacholine (2 μmol/L) to the bath medium (n = 4) caused, after 10-15 s of contact time, a sustained contracture which reached a plateau phase (mean amplitude 0.99 g ± 0.2 g) that persisted until washout. The amplitude of the direct muscular response elicited by methacholine was not influenced by 20 nmol/L ADPN (mean amplitude 0.98 ± 0.3; P > 0.05).

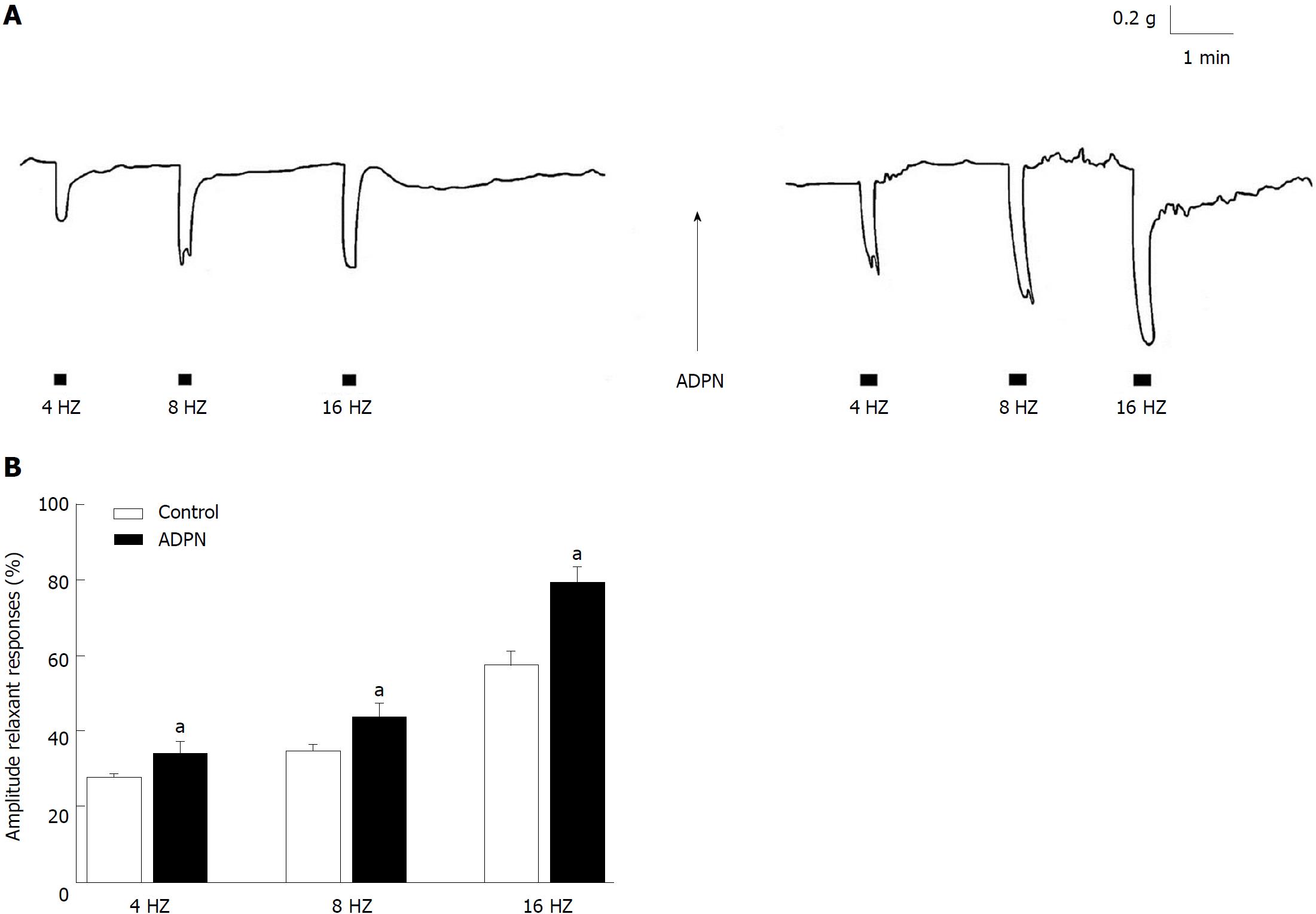

The effects of ADPN on the fundal strips were also tested in NANC conditions. As previously observed[16], CCh (1 μmol/L) induced (n = 18) a contractile response (mean amplitude 1.1 g ± 0.3 g) that reached a plateau phase which persisted until washout. Addition of ADPN (20 nmol/L) to the bath medium caused, in 14 out of the 18 strips examined, a slight (mean amplitude 0.15 g ± 0.02 g) and progressive decay of the basal tension that was not influenced by 1 μmol/L TTX (P > 0.05). In CCh precontracted strips, EFS (4-16 Hz) elicited (n = 16), during the stimulation period, relaxant responses (Figure 2A) whose amplitudes were increased following the addition of ADPN (20 nmol/L) to the bath medium (Figure 2A and B).

By touchdown-PCR analysis ADPN receptors expression, analysed using specific primer pairs for Adipo-R1 and Adipo-R2, has been detected in cDNA in three murine gastric fundus. Two bands corresponding to Adipo-R1 and Adipo-R2 were identified in agarose gel electrophoresis. The positive controls were derived from inguinal fat pad cDNA. A typical experiment from a gastric fundus is shown in Figure 3.

The results of the present study indicate for the first time that ADPN is able to influence the motor responses in strips from the mouse gastric fundus in which we revealed the expression of both Adipo-R1 and Adipo-R2. Particularly, the ability of ADPN to reduce the amplitude of the neurally-induced contractile responses, without affecting the direct muscular response to methacholine, indicates that the hormone exerts a neuromodulatory action. Furthermore, the lack of effects of ADPN on the contraction to methacholine, other than excluding non-specific effects, demonstrated that muscle responsiveness was not compromised.

It is known that gastric motor responses are the result of a balance between nervous excitatory and inhibitory influences on the smooth muscle and that during EFS both excitatory cholinergic and NANC inhibitory nervous fibres are activated. Thus, the reduction in amplitude of the neurally-induced contractile responses by ADPN, observed in the present experiments, may be ascribable to either a minor activation of the excitatory component or to a major nervous inhibitory influence exerted on the smooth muscle. In this view, NO is considered the main NANC inhibitory neurotransmitter released during EFS to cause gastrointestinal relaxation[19,20]. Actually, the increase in amplitude of the EFS-induced contractile responses by the NO synthesis inhibitor L-NNA supports the removal of a nitrergic inhibitory nervous influence. Notably, the observation that ADPN, in the presence of L-NNA, is no longer able to depress the amplitude of the neurally-induced excitatory responses strongly indicates that the nitrergic neurotransmission is involved in the depressant effects of the hormone. This is further confirmed by the ability of ADPN to increase the amplitude of the EFS-induced relaxant responses (elicited by EFS during the stimulation period) whose nitrergic nature has been reported in the mouse gastric fundus[16,21]. Actually, NO appears to be a shared target pathway in the hormonal control of gastrointestinal motility[16,21-24] and thus ADPN effects too may occur, at least in part, through NO. In this view, the ability of the hormone to increase NO synthase expression has been reported in vascular tissues[25,26].

However, in the present study, the observation that ADPN is also able to cause a TTX-insensitive decay of the basal tension indicates that the hormone, in addition to its neuromodulatory effects, exerts a direct muscular action. Experiments are in progress to better clarify these direct effects of ADPN on gastric smooth muscle.

From a physiological point of view, the ability of ADPN to decrease the amplitude of the neurally-induced contractile responses and to enhance that of the relaxant ones, coupled to a decay of the basal tension, suggests that the hormone effects are directed to facilitate gastric relaxation, so increasing the distension of the gastric wall and in turn the organ capacity. Thus, it could be speculated that the effects of ADPN represent a peripheral satiety signal that might contribute to the anorexigenic effects of the hormone[4,27]. In this view, the importance of the gastrointestinal tract in controlling food intake is well recognized[28] and the ability of signals generated in this apparatus to influence food intake through the vagal afferent fibers is well established[29,30]. In this regard, the presence of ADPN receptors in both mucosal and muscular vagal afferents in the gastric antrum of mice has been reported[8], suggesting a stomach-vagal-brain pathway for ADPN to modulate satiety signals. Thus, the observed effects of ADPN on gastric motor responses might be regarded as a reinforcing peripheral mechanism engaged by ADPN to regulate food intake.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates for the first time that ADPN, likely involving the NO pathway, is able to affect the mechanical responses in strips from the mouse gastric fundus. This may furnish the basis to better explore the link between the peripheral and the central effects of ADPN in sending satiety signals and, thus, in the regulation of food intake[31]. Interestingly, clinical evidence of an increased NO production in patients affected by eating disorders, such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, has been reported[32]. Thus, even if caution is needed when transferring data obtained in animal to human, the present results might represent a contribution to consider ADPN as a potential candidate for both novel therapeutic strategies in eating disorders and diagnostic tools.

The adipose-tissue derived hormone adiponectin (ADPN) has been reported to have a role as a key neuromodulator of food intake. It is known that gastrointestinal motor phenomena represent a source of peripheral signals involved in the control of feeding behavior. However, no data are available concerning on the effects of ADPN on gastrointestinal motility. This novel information could highlight an additional mechanism engaged by the hormone in the control of food intake.

The finding that ADPN could influence gastric motility might represent an initial step to regard the peripheral effects of the hormone as possible signals involved in the control of food intake. This aspect, that certainly deserves to be deeper investigated, could lead to consider ADPN as a potential candidate for both novel therapeutic strategies in eating disorders and diagnostic tools.

The main objective of the present study was to investigate the influence of ADPN on the mechanical responses and the expression of its receptors in the mouse gastric fundus.

For the mechanical experiments, longitudinal muscle strips from the mouse gastric fundus were connected to force displacement transducers for continuous recording of isometric tension. The expression of ADPN receptors in gastric fundal tissue was revealed by touchdown- polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis.

The present results highlight that, in the mouse gastric strips, ADPN induces inhibitory effects by decreasing the amplitude of the neurally-induced contractile responses, enhancing that of the relaxant ones and causing a decay of the basal tension. Some of these actions appear to be mediated, at least in part, by nitric oxide although further studies are needed to better clarify the mechanism through which the hormone exerts its effects.

The results of the present study indicate for the first time that ADPN is able to exert inhibitory effects on the mechanical responses of the mouse gastric fundus in which we revealed the expression of ADPN receptors. It could be hypothesized that the hormone effects may be directed to facilitate muscle relaxation, so increasing the distension of the gastric wall that represents a peripheral satiety signal. In this view, the results of the present study may furnish the basis to better explore the link between peripheral and central effects of ADPN in the regulation of food intake.

The results of the present basic research might furnish a contribution to consider ADPN as a potential candidate for both novel therapeutic strategies in eating disorders and diagnostic tools.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Beales ILP S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Yin SY

| 1. | Harwood HJ Jr. The adipocyte as an endocrine organ in the regulation of metabolic homeostasis. Neuropharmacology. 2012;63:57-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fasshauer M, Blüher M. Adipokines in health and disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2015;36:461-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 523] [Cited by in RCA: 750] [Article Influence: 75.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Blüher M, Mantzoros CS. From leptin to other adipokines in health and disease: facts and expectations at the beginning of the 21st century. Metabolism. 2015;64:131-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 275] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 28.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Coope A, Milanski M, Araújo EP, Tambascia M, Saad MJ, Geloneze B, Velloso LA. AdipoR1 mediates the anorexigenic and insulin/leptin-like actions of adiponectin in the hypothalamus. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:1471-1476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Stern JH, Rutkowski JM, Scherer PE. Adiponectin, Leptin, and Fatty Acids in the Maintenance of Metabolic Homeostasis through Adipose Tissue Crosstalk. Cell Metab. 2016;23:770-784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 616] [Cited by in RCA: 741] [Article Influence: 82.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wang ZV, Scherer PE. Adiponectin, the past two decades. J Mol Cell Biol. 2016;8:93-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 285] [Cited by in RCA: 425] [Article Influence: 47.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Thundyil J, Pavlovski D, Sobey CG, Arumugam TV. Adiponectin receptor signalling in the brain. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;165:313-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 223] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kentish SJ, Ratcliff K, Li H, Wittert GA, Page AJ. High fat diet induced changes in gastric vagal afferent response to adiponectin. Physiol Behav. 2015;152:354-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Ito Y, Tsuchida A, Yokomizo T, Kita S, Sugiyama T, Miyagishi M, Hara K, Tsunoda M. Cloning of adiponectin receptors that mediate antidiabetic metabolic effects. Nature. 2003;423:762-769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2258] [Cited by in RCA: 2314] [Article Influence: 105.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | González CR, Caminos JE, Gallego R, Tovar S, Vázquez MJ, Garcés MF, Lopez M, García-Caballero T, Tena-Sempere M, Nogueiras R. Adiponectin receptor 2 is regulated by nutritional status, leptin and pregnancy in a tissue-specific manner. Physiol Behav. 2010;99:91-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Florian V, Caroline F, Francis C, Camille S, Fabielle A. Leptin modulates enteric neurotransmission in the rat proximal colon: an in vitro study. Regul Pept. 2013;185:73-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Okumura T, Nozu T. Role of brain orexin in the pathophysiology of functional gastrointestinal disorders. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26 Suppl 3:61-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Squecco R, Garella R, Luciani G, Francini F, Baccari MC. Muscular effects of orexin A on the mouse duodenum: mechanical and electrophysiological studies. J Physiol. 2011;589:5231-5246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yarandi SS, Hebbar G, Sauer CG, Cole CR, Ziegler TR. Diverse roles of leptin in the gastrointestinal tract: modulation of motility, absorption, growth, and inflammation. Nutrition. 2011;27:269-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Camilleri M. Peripheral mechanisms in appetite regulation. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:1219-1233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Garella R, Idrizaj E, Traini C, Squecco R, Vannucchi MG, Baccari MC. Glucagon-like peptide-2 modulates the nitrergic neurotransmission in strips from the mouse gastric fundus. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:7211-7220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Squecco R, Garella R, Francini F, Baccari MC. Influence of obestatin on the gastric longitudinal smooth muscle from mice: mechanical and electrophysiological studies. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2013;305:G628-G637. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Blüher M, Fasshauer M, Kralisch S, Schön MR, Krohn K, Paschke R. Regulation of adiponectin receptor R1 and R2 gene expression in adipocytes of C57BL/6 mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;329:1127-1132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Min YW, Hong YS, Ko EJ, Lee JY, Ahn KD, Bae JM, Rhee PL. Nitrergic Pathway Is the Main Contributing Mechanism in the Human Gastric Fundus Relaxation: An In Vitro Study. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0162146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Rand MJ. Nitrergic transmission: nitric oxide as a mediator of non-adrenergic, non-cholinergic neuro-effector transmission. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1992;19:147-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 288] [Cited by in RCA: 284] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Vannucchi MG, Garella R, Cipriani G, Baccari MC. Relaxin counteracts the altered gastric motility of dystrophic (mdx) mice: functional and immunohistochemical evidence for the involvement of nitric oxide. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;300:E380-E391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Abot A, Lucas A, Bautzova T, Bessac A, Fournel A, Le-Gonidec S, Valet P, Moro C, Cani PD, Knauf C. Galanin enhances systemic glucose metabolism through enteric Nitric Oxide Synthase-expressed neurons. Mol Metab. 2018;10:100-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Idrizaj E, Garella R, Francini F, Squecco R, Baccari MC. Relaxin influences ileal muscular activity through a dual signaling pathway in mice. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:882-893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Squecco R, Garella R, Idrizaj E, Nistri S, Francini F, Baccari MC. Relaxin Affects Smooth Muscle Biophysical Properties and Mechanical Activity of the Female Mouse Colon. Endocrinology. 2015;156:4398-4410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Chen H, Montagnani M, Funahashi T, Shimomura I, Quon MJ. Adiponectin stimulates production of nitric oxide in vascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:45021-45026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 757] [Cited by in RCA: 754] [Article Influence: 34.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Nour-Eldine W, Ghantous CM, Zibara K, Dib L, Issaa H, Itani HA, El-Zein N, Zeidan A. Adiponectin Attenuates Angiotensin II-Induced Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Remodeling through Nitric Oxide and the RhoA/ROCK Pathway. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Qi Y, Takahashi N, Hileman SM, Patel HR, Berg AH, Pajvani UB, Scherer PE, Ahima RS. Adiponectin acts in the brain to decrease body weight. Nat Med. 2004;10:524-529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 581] [Cited by in RCA: 596] [Article Influence: 28.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Monteiro MP, Batterham RL. The Importance of the Gastrointestinal Tract in Controlling Food Intake and Regulating Energy Balance. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1707-1717.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Bray GA. Afferent signals regulating food intake. Proc Nutr Soc. 2000;59:373-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Cummings DE, Overduin J. Gastrointestinal regulation of food intake. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:13-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 793] [Cited by in RCA: 791] [Article Influence: 43.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wilson JL, Enriori PJ. A talk between fat tissue, gut, pancreas and brain to control body weight. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;418 Pt 2:108-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Vannacci A, Ravaldi C, Giannini L, Rotella CM, Masini E, Faravelli C, Ricca V. Increased nitric oxide production in eating disorders. Neurosci Lett. 2006;399:230-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |