Published online Sep 7, 2018. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i33.3799

Peer-review started: May 30, 2018

First decision: July 6, 2018

Revised: July 9, 2018

Accepted: July 22, 2018

Article in press: July 22, 2018

Published online: September 7, 2018

Processing time: 98 Days and 18.2 Hours

To evaluate the clinical efficacy and safety of an innovative percutaneous transhepatic extraction and balloon dilation (PTEBD) technique for clearance of gallbladder stones in patients with concomitant stones in the common bile duct (CBD).

The data from 17 consecutive patients who underwent PTEBD for clearance of gallbladder stones were retrospectively analyzed. After removal of the CBD stones by percutaneous transhepatic balloon dilation (PTBD), the gallbladder stones were extracted to the CBD and pushed into the duodenum with a balloon after dilation of the sphincter of Oddi. Large stones were fragmented using a metallic basket. The patients were monitored for immediate adverse events including hemorrhage, perforation, pancreatitis, and cholangitis. During the two-year follow-up, they were monitored for stone recurrence, reflux cholangitis, and other long-term adverse events.

Gallbladder stones were successfully removed in 16 (94.1%) patients. PTEBD was repeated in one patient. The mean hospitalization duration was 15.9 ± 2.2 d. Biliary duct infection and hemorrhage occurred in one (5.9%) patient. No severe adverse events, including pancreatitis or perforation of the gastrointestinal or biliary tract occurred. Neither gallbladder stone recurrence nor refluxing cholangitis had occurred two years after the procedure.

Sequential PTBD and PTEBD are safe and effective for patients with simultaneous gallbladder and CBD stones. These techniques provide a new therapeutic approach for certain subgroups of patients in whom endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography/endoscopic sphincterotomy or surgery is not appropriate.

Core tip: Simultaneous gallbladder and common bile duct stones present a challenge in certain subgroups of patients with pulmonary or cardiac comorbidities who cannot tolerate the risk of general anesthesia with tracheal intubation, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography/endoscopic sphincterotomy, or surgery. For these patients, sequential percutaneous transhepatic balloon dilation and percutaneous transhepatic extraction and balloon dilation, providing a path with compliance and only requiring intravenous anesthesia, could be a safe and effective procedure.

- Citation: Liu B, Wu DS, Cao PK, Wang YZ, Wang WJ, Wang W, Chang HY, Li D, Li X, Hertzanu Y, Li YL. Percutaneous transhepatic extraction and balloon dilation for simultaneous gallbladder stones and common bile duct stones: A novel technique. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(33): 3799-3805

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v24/i33/3799.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i33.3799

Gallstones constitute a significant health issue, affecting 10% to 15% of the adult population in developed societies[1,2] and approximately 13% of the Chinese population[3]. Gallstones cause pain and discomfort in the right upper abdomen and are associated with other symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and postprandial fullness, which can seriously affect a patient’s quality of life. In the United States, 20 to 25 million patients are newly diagnosed with gallstones each year, and the medical expenses for the prevention and treatment of gallstone disease reach almost $62 billion annually[1]. The goal of treatment is to resolve ongoing infections, thereby preventing recurrent cholecystitis, subsequent cholangitis, hepatic fibrosis, and progression to cholangiocarcinoma[4].

Approximately 15% of patients with gallbladder stones have concomitant common bile duct (CBD) stones[5]. Open exploration of the CBD was historically the therapeutic option for patients with CBD stones. During recent decades, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) has gained wide acceptance as an effective and minimally invasive alternative. After ERCP/EST, gallbladder stones must be removed through open cholecystectomy, laparoscopic cholecystectomy, or percutaneous cholecystolithotomy. Whether removal of CBD stones should be followed by cholecystectomy to prevent recurrent symptoms has long been debated. Recent prospective randomized trials have indicated benefits of subsequent cholecystectomy[6].

However, some older patients have pulmonary or cardiac comorbidities and cannot tolerate the risk of general anesthesia with tracheal intubation, ERCP/EST, or surgery. Therefore, for treatment of this subgroup, we aimed to evaluate the clinical efficacy of an innovative percutaneous transhepatic extraction and balloon dilation (PTEBD) following percutaneous transhepatic balloon dilation (PTBD).

From December 2013 to June 2014, 17 consecutive patients with 35 simultaneous gallbladder and CBD stones (demonstrated by ultrasonography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography) underwent PTEBD after percutaneous CBD stone removal in our hospital (Table 1). The hospital ethics committee approved this prospective study, and all patients provided written informed consent.

| Characteristic | n (%) |

| No. of patients | 17 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 7 (41.2) |

| Male | 10 (58.8) |

| Comorbidity | |

| Emphysema | 3 (17.6) |

| Pulmonary insufficiency | 5 (29.4) |

| Coronary artery disease | 3 (17.6) |

| Cardiac insufficiency | 5 (29.4) |

| Hypoproteinemia | 1 (6.0) |

| Number of PTEBD procedures | |

| One | 16 (94.1) |

| Two | 1 (5.9) |

| Diameter of stones | |

| < 10 mm | 10 (28.6) |

| 10-20 mm | 21 (60.0) |

| ≥ 20 mm | 4 (11.4) |

| Types of stones | |

| Cholesterol stone | 16 (45.7) |

| Mixed stone | 15 (42.9) |

| Bilirubin stone | 4 (11.4) |

The study included ten men and seven women aged 51 to 79 years with a mean age of 65.8 ± 8.9 years old. All patients suffered from pulmonary or cardiac comorbidities such as emphysema, pulmonary insufficiency, coronary artery disease, cardiac insufficiency, or other conditions that lowered their tolerance for general anesthesia with tracheal intubation, EST, or surgery. Gallbladder and CBD stone diameters ranged from 0.6-2.2 cm. Ten (28.6%) stones were < 10 mm, twenty-one (60%) ranged from 10-20 mm, and four (11.4%) were > 20 mm. Six patients (35.3%) were admitted with acute cholecystitis, nine (52.9%) with acute cholangitis, and two (11.8%) with pancreatitis. PTEBD was repeated in one patient because of overlooked stones. Laboratory values, including WBC count, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), total bilirubin (TBIL), direct bilirubin (DBIL), albumin (ALB) and serum amylase were obtained using routine laboratory tests.

Inclusion criteria were: (1) Concomitant gallbladder and CBD stones with symptoms of acute cholangitis, pancreatitis, or cholecystitis; (2) inability to tolerate or refusal to undergo general anesthesia with tracheal intubation, ERCP/EST, or surgery because of cardiac or lung insufficiency; (3) ERCP/EST not possible due to prior Billroth II surgery; (4) leukocyte count ≥ 4.0 × 109 /L, platelet count ≥ 60 × 109 /L, and hemoglobin concentration ≥ 100 g/L; (5) predicted life span of ≥ 6 mo; and (6) Karnofsky score > 70.

Exclusion criteria were: (1) Concomitant intrahepatic bile duct stones; (2) severe cardiac insufficiency (New York Heart Association class III-IV) or advanced lung disease (determined by consultation with respiratory disease specialists), liver disease (Child-Pugh class C), or kidney disease (grade 3 chronic kidney disease); or (3) severe coagulopathy (prothrombin time > 17 s or platelet count ≤ 60 × 109 /L).

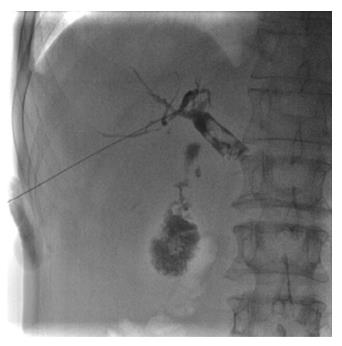

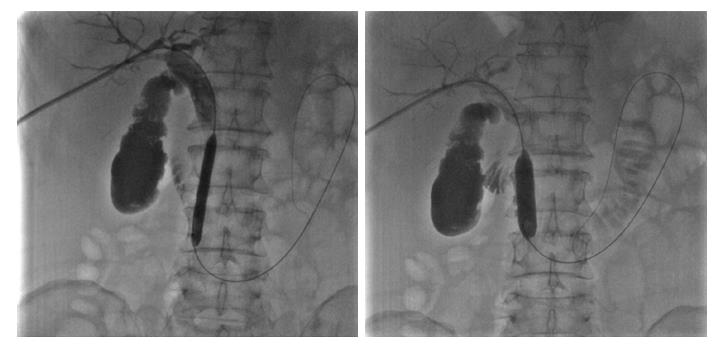

The intrahepatic bile duct was punctured (Figure 1) using conventional percutaneous transhepatic cholangiodrainage with aseptic technique under ultrasonographic and fluoroscopic guidance and intravenous general anesthesia. Cholangiography revealed the number, size, and location of the CBD stones. Balloons (Cristal Balloon; Balt Extrusion, Montmorency, France) sized appropriately for the diameter of the CBD and stones were then introduced crossing the stones using a 0.035-inch-diameter guide wire (Radifocus Guidewire M; Terumo Medical Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), and the sphincter of Oddi was gradually and intermittently dilated (Figure 2)[7]. The sphincter could be dilated to a maximum of 22 mm. The empty balloon was then withdrawn above the stones, inflated, and used to push the stones into the duodenum through the sphincter of Oddi (Figure 3)[8,9]. An 8.5-Fr catheter (COOK Medical, Bloomington, IN 47404, United States) was placed in the CBD for drainage and cholangiography in case of residual stones.

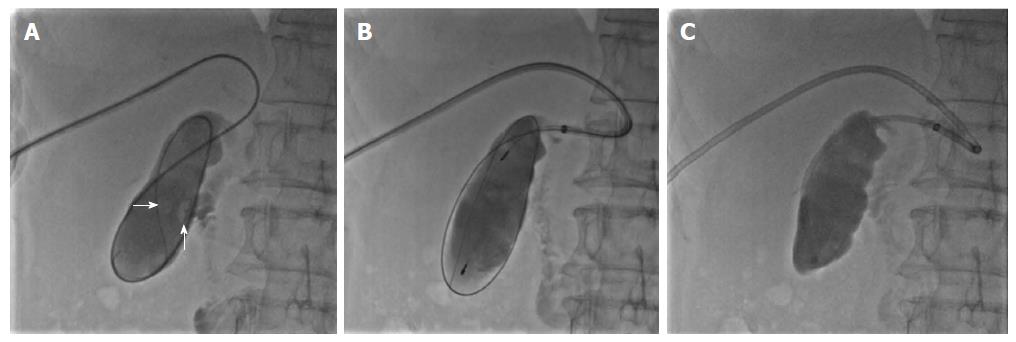

One week after PTBD, contrast was injected through the CBD catheter to perform cholangiography, identifying the anatomic characteristics of the bile duct tree and if there was any residual CBD stones. If yes, PTBD was performed again. If no, a guide wire and a 4-Fr single-angle catheter (Terumo Medical Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) were introduced through the previous transhepatic tract into the gallbladder through the cystic duct in sequence. Cholangiography revealed the number, size, and location of the gallbladder stones (Figure 4A). Large stones were extracted to the CBD with a basket (Olympus, Japan) and then pushed into the duodenum using PTBD (Figure 4B). Sandy stones could be aspirated through a guiding catheter (Launcher, Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, United States) (Figure 4C). An 8.5-Fr drainage catheter was placed in the gallbladder and removed after two weeks without residual stones.

Outcomes recorded included postoperative hospital stay, success rate, causes of failure, and procedure-related complications. The AST, TBIL, DBIL, ALB, serum amylase concentrations, and WBC count were recorded before the procedure and at one week and one month after the procedure. Short-term adverse events, such as biliary duct infection, hemorrhage, pancreatitis, and gastrointestinal and biliary duct perforation were assessed before discharging. Ultrasonography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography were performed at 1, 3, 6, 9, 12, 18 and 24 mo after the procedure. Refluxing cholangitis, and recurrence of gallbladder or CBD stones, considered as long-term complications, were monitored for two years.

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 24.0. Categorical variables were presented as number and percentage. Continuous data were presented as mean ± standard deviation. We used paired t-tests for the same indexes before and after the procedure in the same patient. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 35 gallbladder stones were successfully removed by PTEBD in 16 (94.1%) of the 17 patients. PTEBD was repeated in one patient. The mean hospitalization duration was 15.9 ± 2.2 d.

The diameter of ten stones (28.6%) was smaller than 10 mm, twenty-one stones (60.0%) ranged from 10-20 mm, and four stones (11.4%) were larger than 20 mm. Sixteen stones (45.7%) were cholesterol type, four (11.4%) were bilirubin type, and fifteen (42.9%) were mixed type.

The concentrations of AST, TBIL, DBIL and WBC count declined markedly after PTBD and PTEBD. The differences in these indexes before PTBD, one week after PTBD, and one week after PTEBD were all significant (P < 0.01). In contrast, ALB concentration significantly increased after PTBD and PTEBD (Table 2).

One (5.9%) of the seventeen patients developed a high fever (39.5 °C) and shivering. Escherichia coli was found in the bile, and a biliary duct infection was confirmed. Another patient developed bile duct hemorrhage and recovered after treatment with 1000 IU of reptilase and drainage clamping. No severe adverse events occurred during the perioperative period, including pancreatitis or perforation of the gastrointestinal or biliary duct. Neither recurrence of gallbladder or CBD stones nor refluxing cholangitis had occurred two years after the procedure.

Several different methods for management of simultaneous gallbladder and CBD stones have been proposed and are currently in clinical use[4-6]. Furthermore, since the introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, the frequency of preoperative removal of CBD stones by ERCP/EST has increased[10]. However, certain subgroups of patients cannot tolerate or refuse to undergo general anesthesia with tracheal intubation, ERCP/EST, or surgery due to insufficient pulmonary or cardiac function. In other patients, prior Billroth II surgery causes overwhelming obstacles for endoscopy, preventing subsequent ERCP/EST.

Percutaneous transhepatic papillary dilation was reported to be a safe and effective procedure for CBD stone removal[11-13]. The present study indicates that PTBD and PTEBD are safe and effective and have a low incidence of biliary duct infection and hemorrhage without causing pancreatitis or perforation of the gastrointestinal or biliary duct. Furthermore, because the sphincter of Oddi is preserved, the incidence of late adverse events such as refluxing cholangitis and recurrence of gallbladder and CBD stones is lower than that after EST[14-17].

Theoretically, gallstones can be treated either surgically or nonsurgically after PTBD. In fact, only cholesterol gallstones can be treated without surgery. With a functioning gallbladder, cholesterol gallstones will dissolve slowly when ingestion of ursodiol or chenodiol induces the secretion of unsaturated bile[18]. Stone dissolution could be enhanced by increasing the surface area of the stone via extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, which fragments stones rapidly and safely, accelerating their dissolution rate. Some organic solvents such as methyl tert-butyl ether can be instilled into the gallbladder through a catheter via either a percutaneous transhepatic or endoscopic approach, which also dissolves the stones rapidly[19]. However, gallstones will eventually recur in about 50% of patients who undergo these nonsurgical treatments because the gallbladder is left in place and the fundamental pathogenic abnormalities are not corrected[20]. Compared with surgery (open or laparoscopic cholecystectomy) or nonsurgical medication, PTEBD has the advantages of being less invasive, being well tolerated by patients, and having a lower recurrence rate.

Several key points of PTBD and PTEBD should be addressed: (1) usually puncture of the right front hepatic duct is recommended to obtain a more compliant operating tract; (2) a stiff guide wire is necessary along the puncture tract, bile duct, duodenum, and jejunum for improved balloon support; (3) the sphincter of Oddi should be gradually and intermittently dilated to a maximum diameter of 22 mm to avoid tearing; (4) baskets should be applied for fragmentation of large stones (> 10 mm); (5) aspiration through a guide catheter is usually effective for sandy stones in the gallbladder; and (6) postoperative drainage decompresses the bile duct and decreases the incidence of pancreatitis.

Our study has two main limitations. First, as a pilot study, the number of patients was small. Second, this treatment method is devised for a specific subset of patients in which it has been well tested.

In conclusion, our data indicate that sequential PTBD and PTEBD is a safe, feasible, and effective treatment option for simultaneous gallbladder and CBD stones. It is an innovative alternative procedure for a subgroup of patients who cannot tolerate the risk of general anesthesia. Larger studies and generalizability of the results to more widespread populations will be investigated in the future.

Gallstones constitute a significant health issue, and 15% of these cases have concomitant common bile duct (CBD) stones. Open exploration of CBD, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) followed by open or laparoscopic cholecystectomy may solve the problem.

However, a certain subgroup of patients with pulmonary or cardiac comorbidities cannot tolerate the risk of general anesthesia with tracheal intubation, ERCP/EST, or surgery.

We aimed to evaluate the clinical efficacy of an innovative percutaneous transhepatic extraction and balloon dilation (PTEBD) following percutaneous transhepatic balloon dilation (PTBD).

From December 2013 to June 2014, 17 consecutive patients with 35 simultaneous gallbladder and CBD stones underwent PTEBD after percutaneous CBD stone removal in our hospital. Laboratory values, including WBC count, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), total bilirubin (TBIL), direct bilirubin (DBIL), albumin (ALB) and serum amylase were obtained using routine laboratory tests. Gallbladder and CBD stone diameters ranged from 0.6-2.2 cm. Ten (28.6%) stones were < 10 mm, twenty-one stones ranged from 10-20 mm, and four were > 20 mm. Six patients were admitted with acute cholecystitis, nine with acute cholangitis, and two with pancreatitis. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 24.0. Categorical variables were presented as number and percentage. Continuous data were presented as mean ± standard deviation. We used paired t-tests for the same indexes before and after the procedure in the same patient. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Thirty-five gallbladder stones were successfully removed by PTEBD in 16 of the 17 patients. PTEBD was repeated in one patient. The mean hospitalization duration was 15.9 ± 2.2 d. The concentrations of AST, TBIL, DBIL and WBC count declined markedly after PTBD and PTEBD. The differences in these indexes before PTBD, one week after PTBD, and one week after PTEBD were all significant. In contrast, ALB concentration significantly increased after PTBD and PTEBD. No severe adverse events, including pancreatitis or perforation of the gastrointestinal or biliary duct occurred during the perioperative period. Neither recurrence of gallbladder or CBD stones nor refluxing cholangitis had occurred two years after the procedure.

As our data indicate, sequential PTBD and PTEBD is a safe, feasible, and effective treatment option for simultaneous gallbladder and CBD stones. It is an innovative alternative procedure for a subgroup of patients who cannot tolerate the risk of general anesthesia.

In the future, larger studies and generalizability of the results to more widespread populations will be investigated.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Amin S, Apisarnthanarax S, Currie IS, Marion R S- Editor: Wang XJ L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Huang Y

| 1. | Stinton LM, Shaffer EA. Epidemiology of gallbladder disease: cholelithiasis and cancer. Gut Liver. 2012;6:172-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 556] [Cited by in RCA: 738] [Article Influence: 56.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lammert F, Miquel JF. Gallstone disease: from genes to evidence-based therapy. J Hepatol. 2008;48 Suppl 1:S124-S135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Zhu L, Aili A, Zhang C, Saiding A, Abudureyimu K. Prevalence of and risk factors for gallstones in Uighur and Han Chinese. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:14942-14949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Patrone L, Parthipun A, Diamantopoulos A, Pinna F, Valdata A, Ahmed I, Filauro M, Sabharwal T, de Caro G. Innovative percutaneous antegrade clearance of intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary stones with the use of a hysterosalpingography catheter. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;27:419-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sarli L, Iusco DR, Roncoroni L. Preoperative endoscopic sphincterotomy and laparoscopic cholecystectomy for the management of cholecystocholedocholithiasis: 10-year experience. World J Surg. 2003;27:180-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Almadi MA, Barkun JS, Barkun AN. Management of suspected stones in the common bile duct. CMAJ. 2012;184:884-892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Li YL, Geng JL, Jia YM, Lu HL, Wang W, Liu B, Wang WJ, Chang HY, Wang YZ, Li Z. [Clinical study of percutaneous transhepatic balloon dilation:a novel procedure for common bile duct stone]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2013;93:3586-3589. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Wang W, Wang C, Qi H, Wang Y, Li Y. Percutaneous transcystic balloon dilation for common bile duct stone removal in high-surgical-risk patients with acute cholecystitis and co-existing choledocholithiasis. HPB (Oxford). 2018;20:327-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Li D, Li YL, Wang WJ, Liu B, Chang HY, Wang W, Wang YZ, Li Z. Percutaneous transhepatic papilla balloon dilatation combined with a percutaneous transcystic approach for removing concurrent gallbladder stone and common bile duct stone in a patient with billroth II gastrectomy and acute cholecystitis: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e7964. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Berci G, Morgenstern L. Laparoscopic management of common bile duct stones. A multi-institutional SAGES study. Society of American Gastrointestinal Endoscopic Surgeons. Surg Endosc. 1994;8:1168-1174; discussion 1174-1175. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Shirai N, Hanai H, Kajimura M, Kataoka H, Yoshida K, Nakagawara M, Nemoto M, Nagasawa M, Kaneko E. Successful treatment of percutaneous transhepatic papillary dilation in patients with obstructive jaundice due to common bile duct stones after Billroth II gastrectomy: report of two emergent cases. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;30:91-93. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Gil S, de la Iglesia P, Verdú JF, de España F, Arenas J, Irurzun J. Effectiveness and safety of balloon dilation of the papilla and the use of an occlusion balloon for clearance of bile duct calculi. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174:1455-1460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Park YS, Kim JH, Choi YW, Lee TH, Hwang CM, Cho YJ, Kim KW. Percutaneous treatment of extrahepatic bile duct stones assisted by balloon sphincteroplasty and occlusion balloon. Korean J Radiol. 2005;6:235-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Cuschieri A. Ductal stones: pathology, clinical manifestations, laparoscopic extraction techniques, and complications. Semin Laparosc Surg. 2000;7:246-261. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Fletcher DR. Changes in the practice of biliary surgery and ERCP during the introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy to Australia: their possible significance. Aust NZJ Surg. 1994;64:75-80. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Itoi T, Wang HP. Endoscopic management of bile duct stones. Dig Endosc. 2010;22 Suppl 1:S69-S75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Prat F, Malak NA, Pelletier G, Buffet C, Fritsch J, Choury AD, Altman C, Liguory C, Etienne JP. Biliary symptoms and complications more than 8 years after endoscopic sphincterotomy for choledocholithiasis. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:894-899. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Podda M, Zuin M, Battezzati PM, Ghezzi C, de Fazio C, Dioguardi ML. Efficacy and safety of a combination of chenodeoxycholic acid and ursodeoxycholic acid for gallstone dissolution: a comparison with ursodeoxycholic acid alone. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:222-229. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Zakko SF, Hofmann AF. Microprocessor-assisted solvent transfer system for effective contact dissolution of gallbladder stones. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1990;37:410-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |