Published online Jul 28, 2018. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i28.3155

Peer-review started: March 17, 2018

First decision: April 18, 2018

Revised: May 9, 2018

Accepted: June 22, 2018

Article in press: June 22, 2018

Published online: July 28, 2018

Processing time: 132 Days and 1.9 Hours

To investigate the relationship between the onsets of multikinase inhibitor (MKI)-associated hand-foot skin reaction (HFSR) and prognosis under intervention by pharmacists after the introduction of sorafenib.

We conducted a retrospective study involving 40 patients treated with sorafenib. Intervention by pharmacists began at the time of treatment introduction and continued until the appearance of symptomatic exacerbation or non-permissible adverse reactions. We examined the relationship between MKI-associated HFSR and overall survival (OS) after the initiation of treatment.

The median OS was 10.9 mo in the MKI-associated HFSR group and 3.4 mo in the no HFSR group, showing a significant difference in multivariate analysis. A multivariate analysis of the time to treatment failure indicated that the intervention by pharmacists and MKI-associated HFSR were significant factors. The median cumulative dose and the mean medication possession ratio were significantly higher in the intervention group than in the non-intervention group. A borderline significant difference was observed in terms of OS in this group.

Intervention by pharmacists increased drug adherence. Under increased adherence, MKI-associated HFSR was an advantageous surrogate marker. Intervention by healthcare providers needs to be performed for adequate sorafenib treatment.

Core tip: Sorafenib is an oral anticancer drug associated with a high incidence of adverse reactions. However, no studies have evaluated its therapeutic efficacy under improved adherence. A surrogate marker of significant improvement in overall survival under improved adherence in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients after the introduction of sorafenib was multikinase inhibitor-associated hand-foot skin reaction. Intervention by healthcare providers, including pharmacists specializing in cancer treatment, has improved patient adherence, contributing to the true response to sorafenib treatment.

- Citation: Ochi M, Kamoshida T, Ohkawara A, Ohkawara H, Kakinoki N, Hirai S, Yanaka A. Multikinase inhibitor-associated hand-foot skin reaction as a predictor of outcomes in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sorafenib. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(28): 3155-3162

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v24/i28/3155.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i28.3155

A double-blind, randomized phase III study of sorafenib therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma was previously conducted. The time to progression (TTP) and overall survival (OS) were significantly longer in the sorafenib-treated group than in the placebo group[1-4]. In addition, randomized phase III studies using sunitinib or brivanib have been performed, and no significant differences were observed from sorafenib[5,6]. A randomized phase III study using regorafenib demonstrated that this drug significantly prolonged OS compared with that in the placebo group; however, there is currently no evidence to support regorafenib as a first-choice drug[7].

A surrogate marker that reflects a better prognosis after the introduction of sorafenib has not yet been established[8]. Previous studies have reported a relationship between multikinase inhibitor (MKI)-associated hand-foot skin reaction (HFSR) and TTP/OS[9-12]. Sorafenib frequently induces adverse events (AEs). The most frequent AE is MKI-associated HFSR[1-4]. Although MKI-associated HFSR is not life-threatening, its exacerbation reduces the quality of life of patients, which affects adherence to sorafenib treatments. A previous study indicated that intervention by nurses improved the efficacy of sorafenib treatments[13]; however, intervention by pharmacists who are familiar with sorafenib treatments has not yet been investigated.

The purpose of the present study was to clarify the relationship between therapeutic efficacy and MKI-associated HFSR in sorafenib-treated patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. We also examined the influence of intervention by pharmacists on adherence.

This retrospective study was conducted on patients treated between May 2009 and March 2017 at our institution based on the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) strategy[14,15]. Indication criteria for sorafenib included the following: (1) Child-Pugh grade, A or B; (2) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status, 0 or 1; (3) hemoglobin level, ≥ 8.5 g/dL; (4) neutrophil count, > 1500/μL; (5) platelet count, > 75000/μL; (6) total bilirubin level, < 2.0 mg/dL; (7) alanine and aminotransferases, < 5-fold the upper limit of the normal range; and (8) no necessity for dialysis. Exclusion criteria included the following: (1) A history of serious hypersensitivity to the components of this drug; (2) pregnant women or those who may be pregnant; (3) a history of thrombosis or ischemic heart disease; and (4) brain metastasis. The initial dose of sorafenib was established as 200, 400, or 800 mg, but it was adjusted according to the criteria for dose reductions described in the package inserts or matters recommended by pharmacists. Administration was continued until the appearance of symptomatic exacerbation or non-permissible AEs.

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. The protocol of this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our hospital and was performed according to the Helsinki Declaration.

The treatment response was evaluated using computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging at 8-wk intervals. Radiological evaluations were conducted based on the mRECIST criteria[16]. The National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE) (version 4.0) were adopted to assess AEs. Patients were divided into two groups: Patients who had developed grade 1 or higher MKI-associated HFSR and those who had not.

The Pharmacists’ Outpatient Clinic (primary outpatient clinic) was established through intervention by pharmacists specializing in cancer treatment. At the primary outpatient clinic, AE assessment/management education for patients and residual drug/self-management education were conducted at 2-wk intervals (average). The duration of a consultation at this outpatient clinic per session was 20 min to 30 min. We adopted a system to summarize the results of the consultation at the primary outpatient clinic as a report and advised physicians responsible for outpatient care (secondary outpatient clinic). In addition, when grade 3 or higher AEs occurred, a prompt management system to telephone or directly speak with physicians at the secondary outpatient clinic in addition to reporting was established. At the secondary outpatient clinic, physicians responsible for outpatient care examined patients based on patient information obtained at the primary outpatient clinic and made a final decision on the administration of sorafenib. A system for physicians at the secondary outpatient clinic to promptly consult specialists belonging to each department at the onset of AEs was established. Regarding care for patient anxiety, nurses specializing in cancer nursing arranged an interview- or telephone-based back-up support system. Intervention by pharmacists specializing in cancer treatments began at the time of treatment introduction and continued until the appearance of symptomatic exacerbation or non-permissible AEs.

In the survival analysis, the significance of differences in survival between two groups with and without MKI-associated HFSR after the administration of sorafenib was tested using the log-rank test[17]. The log-rank test was also used to compare survival between two groups with and without intervention by pharmacists. In the multivariate analysis, Cox proportional hazards model was adopted[18]. Regarding the presence or absence of MKI-associated HFSR and antitumor effects, a landmark analysis[19] was conducted to minimize time-dependent bias. AE-free patients 28 d after the start of treatment, when the highest-grade MKI-associated HFSR was noted in ≥ 50% of the patients, was analyzed as a landmark.

Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables. The Mann-Whitney U-test was adopted for continuous variables. SPSS software (version 22, SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, United States) was used for statistical analysis. A P-value of 0.05 considered as significant.

Sorafenib treatment was evaluated in 40 patients treated between May 2009 and March 2017. The baseline characteristics of these patients are shown in Table 1. The median age was 71 years (range: 48-89 years). Thirty-nine patients (97.5%) underwent sorafenib treatment after hepatectomy, radiofrequency ablation, or transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE), which was ineffective. The most frequent etiological factor for hepatitis was hepatitis C virus (57.5%), followed by hepatitis B virus (25%). Extrahepatic metastases were detected in 16 patients (40%), while tumors were localized in the liver in the other 24 patients (60%). Twenty-two patients (55%) had received intervention by pharmacists.

| Patient features | n (%) |

| Total No. of patients | 40 |

| Age (yr) | |

| Median (range) | 71 (48-89) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 31 (78) |

| Female | 9 (12) |

| Child-Pugh class | |

| A | 36 (90) |

| B | 4 (10) |

| Underlying cause | |

| HCV | 23 (58) |

| HBV | 10 (25) |

| Others | 7 (17) |

| Portal vein thrombosis | 11 (28) |

| Liver only | 26 (60) |

| Metastatic disease | 24 (40) |

| AFP (ng/mL) | |

| > 100 | 26 (65) |

| ≤ 100 | 14 (35) |

| DCP (mAU/mL) | |

| > 1000 | 19 (48) |

| ≤ 1000 | 21 (52) |

| BCLC stage | |

| B | 16 (40) |

| C | 24 (60) |

| Intervention by pharmacists | |

| Yes | 22 (55) |

| No | 18 (45) |

AEs related to sorafenib are presented in Table 2. In all patients, ≥ 1 AE was observed, but there were no grade 4 AEs. Primary AEs consisted of MKI-associated HFSR (55%), anemia (35%), hypertension (30%), anorexia (30%), and thrombopenia (30%). The grades of these AEs were evaluated as 1 in 38%, 2 in 35%, and 3 in 28% of patients. In 16 patients, treatments were postponed (definitive discontinuation) due to AEs. In 11 patients, the dose was reduced after definitive discontinuation.

| Adverse events | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | All |

| MKI-associated HFSR | 11 (27) | 6 (15) | 5 (13) | 22 (55) |

| Anemia | 10 (25) | 4 (10) | 0 (0) | 14 (35) |

| Hypertension | 7 (17) | 5 (13) | 0 (0) | 12 (30) |

| Anorexia | 7 (17) | 4 (10) | 1 (3) | 12 (30) |

| Decreased platelet count | 4 (10) | 4 (10) | 4 (10) | 12 (30) |

| Alopecia | 9 (22) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 10 (25) |

| Diarrhea | 5 (13) | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | 7 (17) |

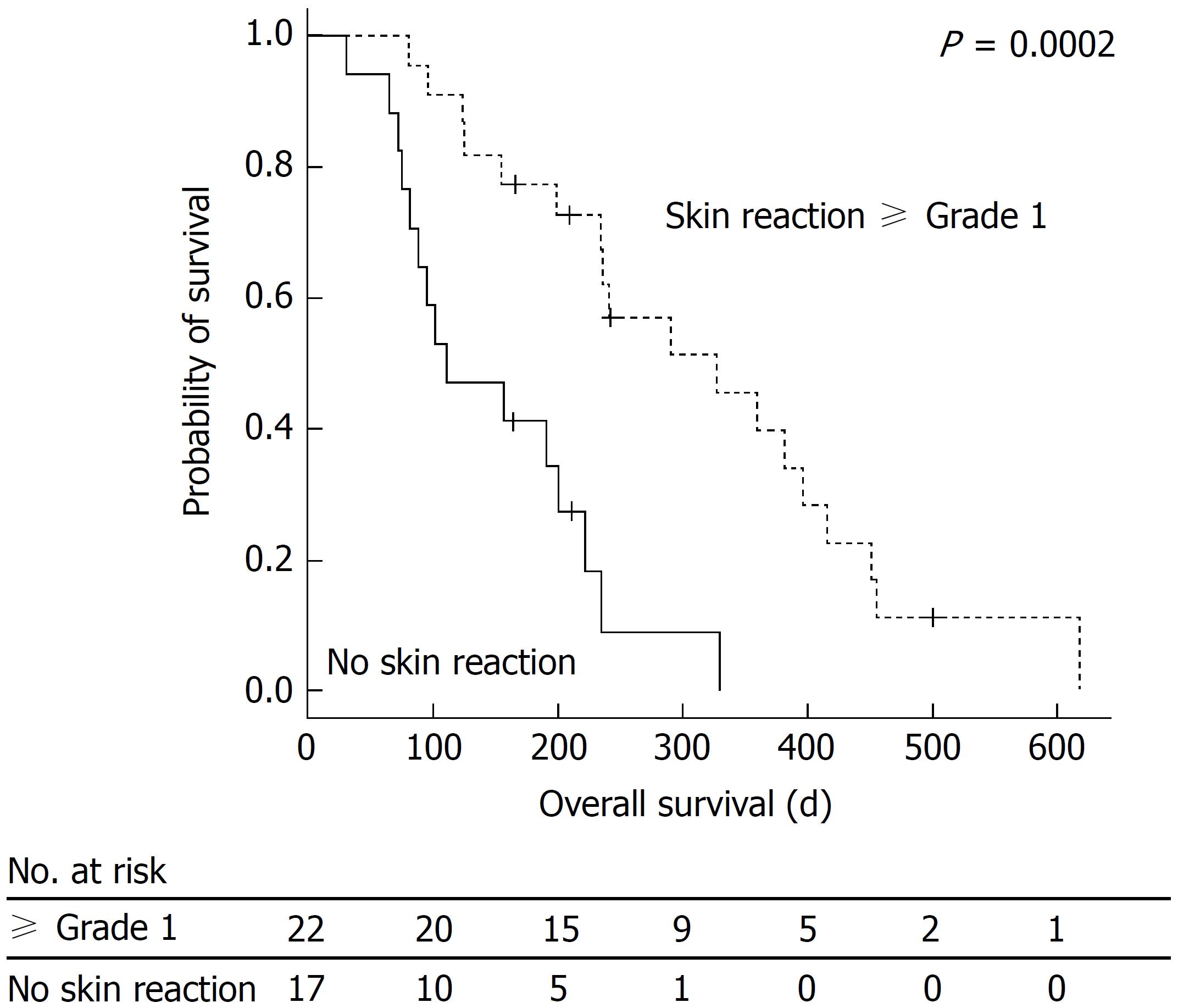

The relationship between OS and MKI-associated HFSR is shown in Figure 1. The median OS was 222 d (7.4 mo) (95%CI: 175-268), range: 14-618 d). In the presence of grade 1 or higher MKI-associated HFSR, OS was significantly prolonged. The results of the univariate- and multivariate analyses regarding OS are presented in Table 3. A multivariate analysis was conducted on factors with P-values of < 0.05 in the univariate analysis. The results of the multivariate analysis showed that the presence of MKI-associated HFSR [hazard ratio (HR) = 0.241, 95%CI: 0.102-0.567; P = 0.001] and BCLC B (HR = 0.404, 95%CI: 0.170-0.964; P = 0.041) were significant predictive factors for the prolongation of OS. No significant differences were observed in the rate of decreased alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels in the early stage, diarrhea, or hypertension. A borderline significant difference was observed in terms of OS between patients with and without intervention by pharmacists (5.2 mo in the non-intervention group vs 9.7 mo in the intervention group, P = 0.097). The disease control rate was 33% [partial response: 1 patient (3%); stable disease: 12 patients (30%)].

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

| HR | P value | HR | P value | 95%CI | |

| Age (≥ 65 yr) | 0.494 | 0.079 | |||

| Initial dose (800 mg) | 1.635 | 0.182 | |||

| Early AFP response | 0.834 | 0.622 | |||

| AFP (< 100 ng/dL) | 0.756 | 0.450 | |||

| DCP (< 1000 mAU/mL) | 0.806 | 0.554 | |||

| MKI-associated HFSR | 0.224 | < 0.001 | 0.241 | 0.001 | 0.102-0.567 |

| BCLC B | 0.358 | 0.013 | 0.404 | 0.041 | 0.170-0.964 |

| Hypertension | 0.889 | 0.756 | |||

| Diarrhea | 0.950 | 0.911 | |||

| Anorexia | 1.671 | 0.162 | |||

| Alopecia | 0.560 | 0.177 | |||

The median time to treatment failure (TTF) was 65 d (2.2 mo) (95% CI: 44-86, range: 7-347 d). The median cumulative dose was 20000 mg (range: 2800-146400 mg). The median cumulative doses in the intervention and non-intervention groups were 32200 mg and 17400 mg, respectively, showing a significant difference (P = 0.047). The median daily dose was 480 mg (range: 392-800 mg). The administration of sorafenib was discontinued in 38 patients for the following reasons: a reduction in the effects of administration in 16 (42%); grade 3 or higher AEs in 14 (36%); exacerbation of the general condition in 4 (11%); and other factors in 4 (11%). The mean medication possession ratios (MPRs) in the intervention and non-intervention groups were 97% and 85%, respectively, showing a significant difference (P < 0.001).

The results of the univariate- and multivariate analyses regarding the TTF are presented in Table 4. The multivariate analysis showed that significant factors for TTF prolongation included intervention by pharmacists (HR = 0.425, 95%CI: 0.186-0.971; P = 0.042) and MKI-associated HFSR (HR = 0.418, 95%CI: 0.175-0.994; P = 0.048). The median TTFs were 145 d (4.8 mo) in the intervention group and 43 d (1.4 mo) in the non-intervention group.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

| HR | P value | HR | P value | 95%CI | |

| Age (≥ 65 yr) | 0.369 | 0.020 | 0.475 | 0.099 | 0.196-1.150 |

| Initial dose (800 mg) | 1.213 | 0.588 | |||

| Early AFP response | 0.630 | 0.24 | |||

| AFP (< 100 ng/dL) | 0.988 | 0.974 | |||

| DCP (< 1000 mAU/mL) | 0.711 | 0.363 | |||

| MKI-associated HFSR | 0.334 | 0.004 | 0.418 | 0.048 | 0.175-0.994 |

| BCLC B | 0.970 | 0.932 | |||

| Hypertension | 1.286 | 0.510 | |||

| Diarrhea | 0.517 | 0.159 | |||

| Anorexia | 1.652 | 0.175 | |||

| Alopecia | 0.337 | 0.019 | 0.792 | 0.679 | 0.262-2.391 |

| Intervention by pharmacists | 0.326 | 0.002 | 0.425 | 0.042 | 0.186-0.971 |

Sorafenib treatment is performed worldwide as evidence-based chemotherapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma[1-4]. A previous study reported that the rate of decreased in AFP levels early after the start of treatment was useful as a surrogate marker for sorafenib therapy[20]. A number of studies have indicated that a relationship exists between AEs after the start of sorafenib administration and antitumor effects; however, this relationship has not yet been confirmed. An international multicenter cooperative study showed by multivariate analysis that diarrhea, hypertension, and HFSR were significant, independent factors associated with OS[21]. In addition, a meta-analysis of the data obtained from 1017 subjects, involving 12 cohort studies, showed that HFSR was a beneficial indicator that improves the prognosis[22].

In the present study, the multivariate analysis of OS showed that MKI-associated HFSR and BCLC B were significant predictive factors for the prolongation of OS. A previous study also indicated that OS was significantly prolonged in the BCLC B group (8.4 mo in BCLC C vs 20.6 mo in BCLC B patients (P < 0.0001))[23]. In the present study, all patients previously underwent TACE, except for one patient, in the BCLC B group (15/16: 94%). Although the introduction of sorafenib for non-responders to TACE may be a good option, the timing of its introduction has not yet been established. Furthermore, a study reported that the combination of sorafenib and TACE improved the TTP[24]. We did not combine sorafenib therapy with other treatments, such as TACE; a surrogate marker for an improvement in OS was obtained by monotherapy with sorafenib. We established a double-check system consisting of primary outpatient care by pharmacists specializing in cancer treatment and secondary outpatient care by physicians. The findings indicated that MKI-associated HFSR was a surrogate marker for OS.

Regarding the TTF, the multivariate analysis showed that intervention by pharmacists and MKI-associated HFSR significantly extended the treatment duration. This finding is consistent with the findings of a previous study indicating that intervention by nurses improved the efficacy of sorafenib treatment[13].

Sorafenib is an MKI with a high incidence of AEs. Primary AEs include HFSR, diarrhea, hypertension, nausea, and hemorrhage. MKI-associated HFSR occurs in approximately 1/3 of patients[25,26]. Furthermore, MKI-associated HFSR differs from previously reported HFSR induced by chemotherapy (e.g., capecitabine, 5-fluorouracil, or doxorubicin)[27,28]. The time to onset of MKI-associated HFSR (14-28 d) is much shorter than that of HFSR induced by chemotherapy, and the site is localized (e.g., areas in contact with shoes). MKI-associated cornification is also prominent. Furthermore, there is no evidence-based rationale to advocate for any of preventive measures for HFSR induced by chemotherapy for the prophylaxis of MKI-associated HFSR[29].

Patients receiving anticancer therapies have been considered to achieve a higher adherence rate than those with other chronic diseases. However, many studies have indicated that the adherence rate is not 100%, even in cancer patients receiving anticancer drugs[30-32]. Concerning the adherence of cancer patients to their treatment with oral anticancer drugs, a previous study investigated breast cancer patients receiving oral anticancer drugs and reported that treatment-associated toxicities affected effective cancer treatments, suggesting the usefulness of adequate interventions for increasing adherence[33]. Furthermore, another study indicated that long-term therapy with oral anticancer drugs reduced the risk of death, while a low adherence rate increased the risk of death[34]. In addition, a decrease in the adherence rates was shown to reduce treatment responses in imatinib-treated patients with chronic myeloid leukemia[32,35].

Insufficient adherence may hinder the effects of oral anticancer drugs. If physicians responsible for prescriptions are unaware of poor adherence, they may change the regimen unnecessarily based on a misunderstanding of disease progression related to insufficient drug effects. Factors associated with non-adherence for a recommended treatment regimen include individual patient characteristics, the features of the disease and treatment regimen, and aspects of the medical care system[36]. Individual factors form a system by influencing each other, and if a patient’s disease is not regarded as a system abnormality, effective treatment may not be achieved. The time to onset of MKI-associated HFSR is much shorter than for that of HFSR induced by chemotherapy. Moreover, there is no evidence-based rationale to advocate for preventive measures for MKI-associated HFSR. Sorafenib treatment is less effective for tumor shrinkage; however, intervention by healthcare providers, including pharmacists with special knowledge, can cover these individual factors. In the present study, the median cumulative doses in the intervention and the non-intervention groups were 32200 mg and 17400 mg, respectively, showing a significant difference (P = 0.047). The MPR was significantly greater in the intervention group than and the non-intervention group, at 97% and 85% respectively, showing a significant difference (P < 0.001); intervention by pharmacists contributed to this increased adherence.

To evaluate the role of MKI-associated HFSR as a surrogate marker for therapeutic effects, we conducted a retrospective analysis involving advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients who had received sorafenib treatment under intervention by pharmacists. The results indicated that MKI-associated HFSR was a surrogate marker for OS under increased adherence. Neither the rate of decrease in AFP levels in the early stage nor diarrhea/hypertension was a surrogate marker. Intervention by pharmacists prolonged the TTF and increased the median cumulative dose and the MPR, resulting in better adherence. A borderline significant difference was observed in terms of OS between patients with and without intervention by pharmacists. The present study had the following limitations: our data are based on a retrospective study, and the sample size was small.

In conclusion, intervention by pharmacists using the double-check system improved drug adherence. Under increased adherence, MKI-associated HFSR in patients receiving sorafenib treatment was a surrogate marker reflecting a better prognosis. Intervention by healthcare providers, including pharmacists with special knowledge, needs to be performed for adequate sorafenib treatment.

A surrogate marker that reflects a better prognosis after the introduction of sorafenib has not yet been established.

The incidence of adverse events after sorafenib introduction is high, reducing drug adherence.

The authors performed intervention by pharmacists using the double-check system to improve drug adherence. In addition, they evaluated a surrogate marker reflecting a better prognosis after sorafenib introduction under increased adherence.

This retrospective study was conducted on advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients who had been treated with sorafenib between May 2009 and March 2017. Establishing the overall survival (OS) as a primary endpoint, the authors evaluated a surrogate marker using multivariate analysis. Furthermore, the effects of intervention by pharmacists on drug adherence were assessed using the time to treatment failure (TTF), median cumulative dose, and medication possession ratio (MPR).

The subjects were 40 patients who had undergone sorafenib therapy. In the presence of grade 1 or higher multikinase inhibitor (MKI)-associated hand-foot skin reaction (HFSR), OS was significantly prolonged. The results of multivariate analysis showed that the presence of MKI-associated HFSR (hazard ratio = 0.241, 95%CI: 0.102-0.567; P = 0.001) was one of the significant predictive factors for the prolongation of OS. There were significant differences in the TTF, median cumulative dose, and MPR between the intervention and non-intervention groups.

Intervention by pharmacists increased the drug adherence. The MKI-associated HFSR was an advantageous surrogate marker under increased adherence. Intervention by healthcare providers needs to be performed for adequate sorafenib treatment.

It remains to be clarified whether intervention by healthcare providers improves the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma patients after sorafenib introduction. Therefore, the double-check system should be further improved, and a larger number of patients should be evaluated. Furthermore, a prospective study should be conducted.

We thank Ms. Aemono (Department of Pharmacy, Hitachi General Hospital) for her advice.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Kao JT S- Editor: Wang JL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Yin SY

| 1. | Bruix J, Raoul JL, Sherman M, Mazzaferro V, Bolondi L, Craxi A, Galle PR, Santoro A, Beaugrand M, Sangiovanni A. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: subanalyses of a phase III trial. J Hepatol. 2012;57:821-829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 565] [Cited by in RCA: 653] [Article Influence: 50.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, de Oliveira AC, Santoro A, Raoul JL, Forner A. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9016] [Cited by in RCA: 10233] [Article Influence: 601.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Cheng AL, Guan Z, Chen Z, Tsao CJ, Qin S, Kim JS, Yang TS, Tak WY, Pan H, Yu S. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma according to baseline status: subset analyses of the phase III Sorafenib Asia-Pacific trial. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:1452-1465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 225] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, Tsao CJ, Qin S, Kim JS, Luo R, Feng J, Ye S, Yang TS. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:25-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3854] [Cited by in RCA: 4637] [Article Influence: 272.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cheng AL, Kang YK, Lin DY, Park JW, Kudo M, Qin S, Chung HC, Song X, Xu J, Poggi G. Sunitinib versus sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular cancer: results of a randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4067-4075. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 523] [Cited by in RCA: 593] [Article Influence: 49.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Johnson PJ, Qin S, Park JW, Poon RT, Raoul JL, Philip PA, Hsu CH, Hu TH, Heo J, Xu J. Brivanib versus sorafenib as first-line therapy in patients with unresectable, advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: results from the randomized phase III BRISK-FL study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3517-3524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 557] [Cited by in RCA: 596] [Article Influence: 49.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bruix J, Qin S, Merle P, Granito A, Huang YH, Bodoky G, Pracht M, Yokosuka O, Rosmorduc O, Breder V. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:56-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2160] [Cited by in RCA: 2701] [Article Influence: 337.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Llovet JM, Peña CE, Lathia CD, Shan M, Meinhardt G, Bruix J; SHARP Investigators Study Group. Plasma biomarkers as predictors of outcome in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:2290-2300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 406] [Cited by in RCA: 454] [Article Influence: 34.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 9. | Vincenzi B, Santini D, Russo A, Addeo R, Giuliani F, Montella L, Rizzo S, Venditti O, Frezza AM, Caraglia M. Early skin toxicity as a predictive factor for tumor control in hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with sorafenib. Oncologist. 2010;15:85-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Otsuka T, Eguchi Y, Kawazoe S, Yanagita K, Ario K, Kitahara K, Kawasoe H, Kato H, Mizuta T; Saga Liver Cancer Study Group. Skin toxicities and survival in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with sorafenib. Hepatol Res. 2012;42:879-886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Di Costanzo GG, Tortora R, Iodice L, Lanza AG, Lampasi F, Tartaglione MT, Picciotto FP, Mattera S, De Luca M. Safety and effectiveness of sorafenib in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in clinical practice. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44:788-792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Reig M, Torres F, Rodriguez-Lope C, Forner A, LLarch N, Rimola J, Darnell A, Ríos J, Ayuso C, Bruix J. Early dermatologic adverse events predict better outcome in HCC patients treated with sorafenib. J Hepatol. 2014;61:318-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Shomura M, Kagawa T, Shiraishi K, Hirose S, Arase Y, Koizumi J, Mine T. Skin toxicity predicts efficacy to sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol. 2014;6:670-676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bruix J, Sherman M; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020-1022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5972] [Cited by in RCA: 6560] [Article Influence: 468.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Forner A, Llovet JM, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2012;379:1245-1255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3249] [Cited by in RCA: 3587] [Article Influence: 275.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 16. | Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30:52-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2583] [Cited by in RCA: 3277] [Article Influence: 218.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (36)] |

| 17. | Peto R, Pike MC, Armitage P, Breslow NE, Cox DR, Howard SV, Mantel N, McPherson K, Peto J, Smith PG. Design and analysis of randomized clinical trials requiring prolonged observation of each patient. II. analysis and examples. Br J Cancer. 1977;35:1-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5822] [Cited by in RCA: 5949] [Article Influence: 123.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cox DR. Regression models and life tables. J R Stat Soc B. 1972;34:187-220. |

| 19. | Anderson JR, Cain KC, Gelber RD. Analysis of survival by tumor response. J Clin Oncol. 1983;1:710-719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 870] [Cited by in RCA: 937] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Personeni N, Bozzarelli S, Pressiani T, Rimassa L, Tronconi MC, Sclafani F, Carnaghi C, Pedicini V, Giordano L, Santoro A. Usefulness of alpha-fetoprotein response in patients treated with sorafenib for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;57:101-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Howell J, Pinato DJ, Ramaswami R, Bettinger D, Arizumi T, Ferrari C, Yen C, Gibbin A, Burlone ME, Guaschino G. On-target sorafenib toxicity predicts improved survival in hepatocellular carcinoma: a multi-centre, prospective study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:1146-1155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wang P, Tan G, Zhu M, Li W, Zhai B, Sun X. Hand-foot skin reaction is a beneficial indicator of sorafenib therapy for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;12:1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Iavarone M, Cabibbo G, Piscaglia F, Zavaglia C, Grieco A, Villa E, Cammà C, Colombo M; SOFIA (SOraFenib Italian Assessment) study group. Field-practice study of sorafenib therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective multicenter study in Italy. Hepatology. 2011;54:2055-2063. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 287] [Cited by in RCA: 299] [Article Influence: 21.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Li J, Liu W, Zhu W, Wu Y, Wu B. Transcatheter hepatic arterial chemoembolization and sorafenib for hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind controlled trials. Oncotarget. 2017;8:59601-59608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Chu D, Lacouture ME, Fillos T, Wu S. Risk of hand-foot skin reaction with sorafenib: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Oncol. 2008;47:176-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lacouture ME, Wu S, Robert C, Atkins MB, Kong HH, Guitart J, Garbe C, Hauschild A, Puzanov I, Alexandrescu DT. Evolving strategies for the management of hand-foot skin reaction associated with the multitargeted kinase inhibitors sorafenib and sunitinib. Oncologist. 2008;13:1001-1011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 230] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Autier J, Mateus C, Wechsler J, Spatz A, Robert C. [Cutaneous side effects of sorafenib and sunitinib]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2008;135:148-153; quiz 147, 154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Heidary N, Naik H, Burgin S. Chemotherapeutic agents and the skin: An update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:545-570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Anderson R, Jatoi A, Robert C, Wood LS, Keating KN, Lacouture ME. Search for evidence-based approaches for the prevention and palliation of hand-foot skin reaction (HFSR) caused by the multikinase inhibitors (MKIs). Oncologist. 2009;14:291-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Partridge AH, Archer L, Kornblith AB, Gralow J, Grenier D, Perez E, Wolff AC, Wang X, Kastrissios H, Berry D. Adherence and persistence with oral adjuvant chemotherapy in older women with early-stage breast cancer in CALGB 49907: adherence companion study 60104. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2418-2422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Noens L, van Lierde MA, De Bock R, Verhoef G, Zachée P, Berneman Z, Martiat P, Mineur P, Van Eygen K, MacDonald K. Prevalence, determinants, and outcomes of nonadherence to imatinib therapy in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia: the ADAGIO study. Blood. 2009;113:5401-5411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 421] [Cited by in RCA: 456] [Article Influence: 28.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Marin D, Bazeos A, Mahon FX, Eliasson L, Milojkovic D, Bua M, Apperley JF, Szydlo R, Desai R, Kozlowski K. Adherence is the critical factor for achieving molecular responses in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia who achieve complete cytogenetic responses on imatinib. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2381-2388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 605] [Cited by in RCA: 694] [Article Influence: 46.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Hershman DL, Kushi LH, Shao T, Buono D, Kershenbaum A, Tsai WY, Fehrenbacher L, Gomez SL, Miles S, Neugut AI. Early discontinuation and nonadherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy in a cohort of 8,769 early-stage breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4120-4128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 652] [Cited by in RCA: 647] [Article Influence: 43.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | McCowan C, Shearer J, Donnan PT, Dewar JA, Crilly M, Thompson AM, Fahey TP. Cohort study examining tamoxifen adherence and its relationship to mortality in women with breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:1763-1768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Ibrahim AR, Eliasson L, Apperley JF, Milojkovic D, Bua M, Szydlo R, Mahon FX, Kozlowski K, Paliompeis C, Foroni L. Poor adherence is the main reason for loss of CCyR and imatinib failure for chronic myeloid leukemia patients on long-term therapy. Blood. 2011;117:3733-3736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 213] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Ruddy K, Mayer E, Partridge A. Patient adherence and persistence with oral anticancer treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:56-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 406] [Cited by in RCA: 437] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |