Published online Jun 21, 2018. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i23.2491

Peer-review started: March 16, 2018

First decision: March 30, 2018

Revised: April 5, 2018

Accepted: May 18, 2018

Article in press: May 18, 2018

Published online: June 21, 2018

Processing time: 91 Days and 20.4 Hours

To compare the efficacy, improved quality of life, and prognosis in patients undergoing either subtotal colonic bypass with antiperistaltic cecoproctostomy (SCBAC) or subtotal colonic bypass plus colostomy with antiperistaltic cecoproctostomy (SCBCAC) for the treatment of slow transit constipation.

Between October 2010 and October 2014, aged patients with slow transit constipation who were hospitalized and underwent laparoscopic surgery in our institute were divided into two groups: the bypass group, 15 patients underwent SCBAC, and the bypass plus colostomy group, 14 patients underwent SCBCAC. The following preoperative and postoperative clinical data were collected: gender, age, body mass index, operative time, first flatus time, length of hospital stay, bowel movements (BMs), Wexner fecal incontinence scale, Wexner constipation scale (WCS), gastrointestinal quality of life index (GIQLI), numerical rating scale for pain intensity (NRS), abdominal bloating score (ABS), and Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications (CD) before surgery and at 3, 6, 12, and 24 mo after surgery.

All patients successfully underwent laparoscopic surgery without open surgery conversion or surgery-related death. The operative time and blood loss were significantly less in the bypass group than in the bypass plus colostomy group (P = 0.007). No significant differences were observed in first flatus time, length of hospital stay, or complications with CD > 1 between the two groups. No patients had fecal incontinence after surgery. At 3, 6, and 12 mo after surgery, the number of BMs was significantly less in the bypass plus colostomy group than in the bypass group. The parameters at 3, 6, 12, and 24 mo after surgery in both groups significantly improved compared with the preoperative conditions (P < 0.05), except NRS at 3, 6 mo after surgery in both groups, ABS at 12, 24 mo after surgery and NRS at 12, 24 mo after surgery in the bypass group. WCS, GIQLI, NRS, and ABS significantly improved in the bypass plus colostomy group compared with the bypass group at 3, 6, 12, and 24 mo after surgery (P < 0.05) except WCS, NRS at 3, 6 mo after surgery and ABS at 3 mo after surgery. At 1 year after surgery, a barium enema examination showed that the emptying time was significantly better in the bypass plus colostomy group than in the bypass group (P = 0.007).

Laparoscopic SCBCAC is an effective and safe procedure for the treatment of slow transit constipation in an aged population and can significantly improve the prognosis. Its clinical efficacy is more favorable compared with that of SCBAC. Laparoscopic SCBCAC is a better procedure for the treatment of slow transit constipation in an aged population.

Core tip: Constipation is one of the most common gastrointestinal symptoms. From October 2010 to October 2014, we employed laparoscopic subtotal colonic bypass plus colostomy with antiperistaltic cecoproctostomy (SCBCAC) to treat aged patients with constipation and conducted a retrospective control study in comparison with subtotal colonic bypass with antiperistaltic cecoproctostomy (SCBAC). From our study, we concluded that laparoscopic SCBCAC is an effective and safe procedure for the treatment of slow transit constipation in an aged population and can significantly improve the prognosis. Its clinical efficacy is more favorable compared with that of SCBAC.

- Citation: Yang Y, Cao YL, Wang WH, Zhang YY, Zhao N, Wei D. Subtotal colonic bypass plus colostomy with antiperistaltic cecoproctostomy for the treatment of slow transit constipation in an aged population: A retrospective control study. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(23): 2491-2500

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v24/i23/2491.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i23.2491

Constipation is one of the most common gastrointestinal symptoms. Generally, the incidence is 16% in females and 12% in males, but it affects more than 30% of the aged population[1] and seriously alters the life quality of patients. In terms of treatments for constipation[2], surgery is a common approach for treatment of intractable slow transit constipation (STC), especially for those with poor responses to conservative treatment. One of the two commonly used surgical approaches is total colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis (TC-IRA), which is widely used in the treatment of slow transit constipation because of its high cure rate[3-5]. Although constipation is alleviated, the main problem after surgery is the increased number of bowel movements (BMs), which causes some patients to suffer from abdominal pain, abdominal bloating, refractory diarrhea, loss of nutrients, and intestinal obstruction[5-8]. The other surgical approach is subtotal colectomy with cecorectal anastomosis (SCCRA)[9,10], which preserves the ileocecal valve and partial colon to be conducive to the absorption of water, electrolytes, bile salts, and vitamins and can alleviate severe postoperative diarrhea. More importantly, SCCRA is associated with a lower incidence of intestinal obstruction and can considerably improve the life quality of patients[11-14]. Based on different anastomosis sites, SCCRA is divided into two procedures: subtotal colectomy with isoperistaltic cecorectal anastomosis (SCICRA) and subtotal colectomy with antiperistaltic cecorectal anastomosis (SCACRA). SCICRA requires rotation of the ileocecal junction, which may easily lead to blood vessel torsion and poor blood circulation[9,15-19]. In contrast, SCACRA does not require rotation of the ileocecal junction and can avoid causing blood vessel torsion. Additionally, the function of the ileocecal junction is preserved. Thus, the SCACRA surgical method maintains the physiological anatomy[10,20-25]. Although the abovementioned methods have good efficacy in the treatment of slow transit constipation, they are not suitable for aged patients or patients in poor physical condition because of the large wound produced and the length of the operation; these patients need non-surgical treatments. After long-term treatment with oral laxative agents, the patients become nonresponsive to these agents and have to undergo enema administration periodically to alleviate their constipation. Some patients cannot tolerate the suffering of constipation and have to choose ileostomy, which considerably impacts the quality of life of patients. In 2010, Yong-Gang Wang reported a subtotal colonic bypass with antiperistaltic cecoproctostomy (SCBAC) via an abdominal approach to treat slow transit constipation. In Wang’s study, the average patient age was 51 years (range: 28-75 years). In patients who received 1-year follow-up, the alleviation rate of constipation was up to 75% (9/12)[26]. The procedure Wang used involved closing the distal portion of the cecum, after which side-side anastomosis was performed between the blinding end of the cecum and the rectum. In 2010, we performed four laparoscopic SCBACs in patients over 70 years old. After surgery, two patients experienced severe abdominal pain, abdominal bloating, rectal discomfort, and tenesmus. They did not respond to oral laxatives and required enemas for daily BMs. We examined these four patients with barium enemas and found barium retention in the excluded colon for 84 h in one case and 300 h in another. Therefore, we considered that the patient’s postoperative symptoms may be related to the retention of indigested food and feces in the excluded colon. If the upper portion of the rectum was occluded with end-side anastomosis between the cecum and rectum, the excluded colon could become a closed loop. Thus, colonic mucus and fluid cannot be discharged, and observation of the excluded colon becomes impossible, which may cause delays in the detection and treatment of potential colonic lesions. From October 2010 to October 2014, we employed laparoscopic subtotal colonic bypass plus colostomy with antiperistaltic cecoproctostomy (SCBCAC) to treat aged patients with constipation and conducted a retrospective control study in comparison with SCBAC.

This was a two-phase study conducted in the Institute of Anal-Colorectal Surgery of PLA. From October 2010 to June 2012, 15 consecutive patients over 70 years old underwent laparoscopic SCBAC (LSCBAC); this group of patients was defined as the bypass group. From July 2012 to October 2014, 15 consecutive patients over 70 years old underwent laparoscopic SCBCAC (LSCBCAC); this group of patients was defined as the bypass plus colostomy group. Follow-ups were performed in these two groups of patients for more than 2 years. One patient in the bypass plus colostomy group was lost during follow-up. The preoperative examination included colonic transit test, defecography, colonoscopy, electromyography, anorectal manometry, and routine preoperative examination for colonic resection.

The surgical indications for this study are described as follows. Inclusion criteria: (1) The Rome III diagnosis criteria for constipation; (2) confirmed diagnosis of slow colon transit constipation (at least two positive colonic transit tests were recorded before surgery); (3) chronic (non-surgical treatment for more than 5 years), severe (WCS > 15), refractory (long-term dependence on high-dose laxative or application of enema) slow transit constipation; and (4) age ≥ 70 years. The exclusion criteria included: (1) American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score > 3; (2) liver and kidney dysfunction; (3) patients with psychological symptoms or with history of mental illness, such as rectal abuse, vaginal abuse, etc.; (4) patients with obvious signs of outlet obstruction (such as frequent defecation, difficult defecation without dry feces, and anorectal dysfunction); (5) patients with a history of major abdominal surgery; (6) exclusion of organic colon disease; and (7) patients with life-threatening diseases, such as cancer.

Each procedure was performed by the same surgical team of the Institute of Anal-Colorectal Surgery of PLA. The patients were placed in the Trendelenburg position (≤ 15°) with legs apart. The pneumoperitoneum was maintained at 8 kPa or less. In the bypass plus colostomy group, laparoscopy was performed via five incisions. The five trocars were placed as follows: trocar 1 was placed at a site 0.5-1 cm above the umbilicus, trocar 2 was placed at the lateral margin of the left rectus abdominis muscle 4 cm below the umbilicus, trocar 3 was placed at the lateral margin of the left rectus abdominis muscle 2 cm above the umbilicus, and trocars 4 and 5 were placed at the mirror position of trocars 2 and 3 at the lateral margin of the right rectus abdominis muscle. The surgeon stood on the left side of the patient to mobilize the ileocecal junction and the ascending colon and to lower the ileocecal junction down to the pelvic inlet with preservation of the blood supply. A laparoscopic linear cutting stapler with a 45-mm green staple unit was used to transect the ascending colon at a site 2-3 cm distal to the ileocecal junction. Then, the appendix was excised. The surgeon then moved to the right side of the patient to dissect the lateral peritoneum of the sigmoid colon. At a site 4-6 cm above the peritoneal fold or at the level of the sacral promontory, a laparoscopic linear cutting stapler with a 45-mm green staple unit was used to transect the upper rectum after dissection of the rectal mesentery and ligation of the marginal arteries. The lower right abdominal incision was extended to the desired length. The head of a 29- to 33-mm circular stapler was placed in the bottom of the cecum. The shaft of the stapler was placed in the rectum via the anal canal to complete end-side anastomosis (end rectum to lateral cecum). The ileocecal junction did not need rotation. The lower left abdominal incision was extended to desired length. The end of the rectal-sigmoid colon was used for colostomy via an extraperitoneal approach. At the end of the procedure, a drainage tube was placed in the Douglas’ pouch.

In the bypass group, laparoscopy was performed via three incisions. The placements of trocars 1, 2, and 3 were the same as in the bypass plus colostomy group. The surgeon stood on the left side of the patient, and the surgical procedures were the same as those of the bypass plus colostomy group except for the rectal transection. The shaft of the stapler was placed in the rectum via the anal canal to complete side-side anastomosis between the right wall of the rectum and the cecum at the level above the rectal ampulla or sacral promontory. At the end of the procedure, a drainage tube was placed in the Douglas’ pouch.

The following statistical data were collected: (1) Patient sex, age, and body mass index (BMI); (2) surgical parameters (operative time and blood loss); and (3) postoperative recovery (first flatus time, length of hospital stay, and postoperative complications). The following clinical data were collected before surgery and 3, 6, and 12 mo after surgery: the number of daily BMs and the Wexner incontinence scale (WIS, on a scale of 0-20, in which 0 represents the best and 20 represents complete incontinence)[4]. The following clinical data were collected before surgery and 3, 6, 12, and 24 mo after surgery: The Wexner constipation scale[27] (WCS, on a scale of 0-30 in which the higher score represents more severe constipation; the scores of healthy individuals are less than 8), the gastrointestinal quality of life index[28] (GIQLI, on a scale of 0-144 in which (125.80 ± 13.00) represents the index in healthy population), abdominal pain intensity indicated by the numerical rating scale (0-10)[29] (NRS, 0-3: Mild pain and no impact on sleep; 4-6: Moderate tolerable pain and mild impact on sleep; 7-10: Severe pain and serious impact on sleep), and the abdominal bloating score (ABS, the score is inferred from the GIQLI scoring table, from 0-4: 0 = absent; 1 = occasionally; 2 = sometimes; 3 = most of the time; 4 = all the time). Symptoms with scores > 1 were defined as surgery-related abdominal pain and bloating, and symptoms with scores ≥ 3 were defined as severe postoperative frequent abdominal pain and bloating. The Clavien-Dindo classification[30] was used to assess surgical complications. The complications defined as class II or above were studied. All postoperative data were obtained from the questionnaire by clinical visit or telephone follow-up. This study began in October 2012.

We compared the postoperative parameters at 3, 6, 12, and 24 mo after surgery of the two groups, including the WCS, ABS, GIQLI, and NRS with preoperative parameters. We studied the variations in parameters among patients in each group. We also compared the postoperative parameters between the two groups at 3, 6, 12, and 24 mo after surgery, including the WIS, WCS, ABS, GIQLI, NRS, and BM. Thus, the effects of two different surgical methods for the treatment of STC patients were evaluated.

The variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). T-tests were used for the comparison of paired data at different time points within each group. For the comparison of data between the two groups, independent samples t-test and Fisher’s exact test were applied. For the comparison of postoperative functional recovery (WIS, WCS, ABS, GIQLI, NRS, and BM) between groups, analysis of covariance was applied. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data were analyzed using SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States).

Patient characteristics were not significantly different between the two groups. Both groups predominantly consisted of females, with ages ranging from 70 to 80 years. The average age was 74.86 ± 3.42 in the bypass plus colostomy group and 74.73 ± 3.11 in the bypass group. All patients in both groups suffered from severe constipation before surgery. The preoperative WCS scores were 16.86 ± 1.56 and 16.93 ± 1.16 in the bypass plus colostomy group and the bypass group, respectively. The preoperative GIQLI scores were very low in both groups (64.00 ± 3.51 and 63.20 ± 2.40 in the bypass plus colostomy group and the bypass group, respectively). No patient in either group experienced fecal incontinence but somewhat suffered from abdominal pain and bloating (Table 1).

| Bypass plus colostomy group (n = 14) | Bypass group (n = 15) | P value | |||

| Basic information | Sex | M/F | 6/8 | 5/10 | 0.710 |

| Age | yr | 74.86 ± 3.42 | 74.73 ± 3.11 | 0.919 | |

| BMI | kg/m2 | 20.03 ± 1.09 | 20.27 ± 1.39 | 0.612 | |

| Preoperative data | WCS | (0-30) | 16.86 ± 1.56 | 16.93 ± 1.16 | 0.882 |

| GIQLI | (0-144) | 64.00 ± 3.51 | 63.20 ± 2.40 | 0.477 | |

| ABS | (0-4) | 2.71 ± 0.73 | 2.40 ± 0.63 | 0.224 | |

| NRS | (0-10) | 3.00 ± 1.04 | 2.87 ± 1.30 | 0.764 | |

| Operative and postoperative data | Operative time | min | 42.67 ± 3.35 | 36.86 ± 4.06 | < 0.001 |

| Blood loss | mL | 14.43 ± 3.11 | 11.13 ± 2.95 | 0.007 | |

| First flatus time | d | 1.86 ± 1.03 | 2.20 ± 0.78 | 0.317 | |

| Hospital stay | d | 14.00 ± 1.66 | 13.67 ± 2.13 | 0.644 | |

| Morbidity (Dindo > I) | n (%) | 1 (7.14) | 1 (6.67) | 0.960 |

All patients successfully underwent laparoscopic surgery without open surgery conversion or surgery-related death. The operative times were short in both groups (42.67 ± 3.35 min in the bypass plus colostomy group and 36.56 ± 4.06 min in the bypass group). However, the operative time was significantly longer in the bypass plus colostomy group than in the bypass group (P < 0.001). The blood loss was negligible in both groups (14.43 ± 3.11 mL in the bypass plus colostomy group and 11.13 ± 2.93 mL in the bypass group). However, the blood loss was significantly less in the bypass group than in the bypass plus colostomy group (P = 0.007). No significant differences were observed in first flatus time or length of hospital stay between the two groups (P = 0.317 and P = 0.644, respectively). We compared each complication of Clavien-Dindo > 1 and did not note differences between the groups (P = 0.007) (Table 1). No anastomotic leakage was reported in either group, but one case of pneumonia was reported in each group. Both cases of pneumonia were cured. No patients had fecal incontinence after surgery. At 3, 6, and 12 mo after surgery, the WIS was significantly better, and the number of BMs was significantly less in the bypass plus colostomy group than in the bypass group.

Functional recovery compared at different time points within the same group: WCS and GIQLI significantly improved (P < 0.001) at 3, 6, 12, and 24 mo after surgery in both groups. In the bypass plus colostomy group, NRS significantly improved at 12 and 24 mo after surgery (P < 0.001); ABS significantly improved (P < 0.001) at 3, 6, 12, and 24 mo after surgery. In the bypass group, NRS did not improve at 3, 6, 12, and 24 mo after surgery; ABS significantly improved (P = 0.003) at 3 and 6 mo but did not improve at 12 and 24 mo after surgery (P = 0.207 and P = 0.670, respectively) (Table 2).

| Bypass plus colostomy group (n = 14) | Bypass group (n = 15) | |||||||

| Preoperative | Postoperative | P value | Preoperative | Postoperative | P value | |||

| WCS | 16.86 ± 1.56 | 3 mo | 2.71 ± 2.30 | < 0.001 | 16.93 ± 1.16 | 3 mo | 4.33 ± 3.83 | < 0.001 |

| 6 mo | 2.64 ± 2.50 | < 0.001 | 6 mo | 5.07 ± 4.06 | < 0.001 | |||

| 12 mo | 2.36 ± 2.13 | < 0.001 | 12 mo | 6.40 ± 5.16 | < 0.001 | |||

| 24 mo | 1.86 ± 1.46 | < 0.001 | 24 mo | 6.60 ± 5.42 | < 0.001 | |||

| GIQLI | 64.00 ± 3.51 | 3 mo | 106.57 ± 5.79 | < 0.001 | 63.20 ± 2.40 | 3 mo | 88.27 ± 12.26 | < 0.001 |

| 6 mo | 114.50 ± 7.59 | < 0.001 | 6 mo | 95.13 ± 14.87 | < 0.001 | |||

| 12 mo | 119.79 ± 8.24 | < 0.001 | 12 mo | 97.60 ± 18.38 | < 0.001 | |||

| 24 mo | 122.21 ± 6.85 | < 0.001 | 24 mo | 98.47 ± 18.09 | < 0.001 | |||

| ABS | 2.71 ± 0.73 | 3 mo | 1.29 ± 0.83 | < 0.001 | 2.40 ± 0.63 | 3 mo | 1.53 ± 0.83 | 0.003 |

| 6 mo | 0.86 ± 0.77 | < 0.001 | 6 mo | 1.67 ± 0.82 | 0.003 | |||

| 12 mo | 0.86 ± 0.66 | < 0.001 | 12 mo | 2.07 ± 0.88 | 0.207 | |||

| 24 mo | 0.79 ± 0.70 | < 0.001 | 24 mo | 2.27 ± 1.16 | 0.670 | |||

| NRS | 3.00 ± 1.04 | 3 mo | 2.50 ± 1.29 | 0.187 | 2.87 ± 1.30 | 3 mo | 3.27 ± 1.34 | 0.320 |

| 6 mo | 2.21 ± 1.47 | 0.094 | 6 mo | 3.53 ± 2.00 | 0.126 | |||

| 12 mo | 1.14 ± 0.86 | < 0.001 | 12 mo | 3.93 ± 2.92 | 0.123 | |||

| 24 mo | 1.07 ± 0.62 | < 0.001 | 24 mo | 4.07 ± 3.04 | 0.105 | |||

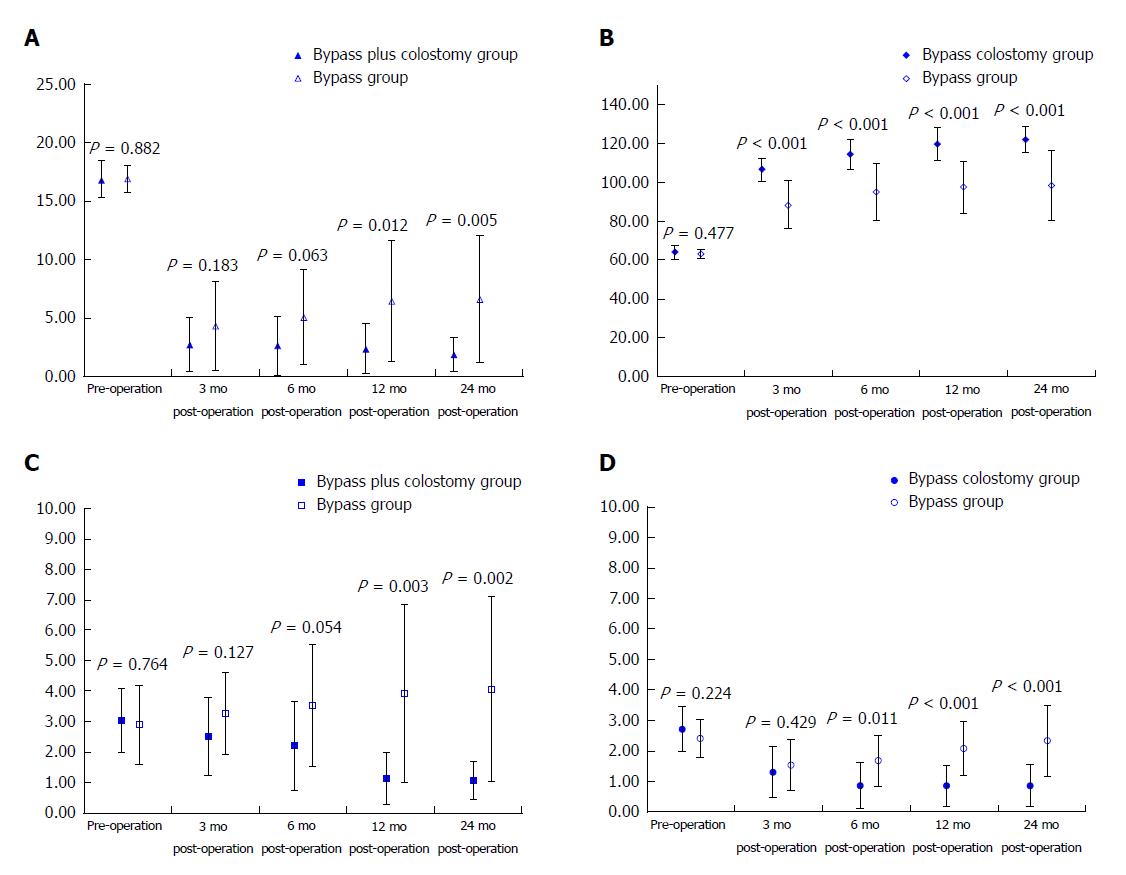

Functional recovery compared between groups: At 3, 6, 12, and 24 mo after surgery, WCS, GIQLI, NRA, and ABS were compared between the two groups. WCS and NRS remained unimproved at 3 and 6 mo after surgery, and ABS remained unchanged at 3 mo after surgery. Additional above-noted parameters were significantly better in the bypass plus colostomy group than in the bypass group at each time point. These improvements continued over the time course, as shown in Figure 1 and Table 3.

| Time (postoperative) | Bypass plus colostomy group (n = 14) | Bypass group (n = 15) | P value | |

| Barium emptying times | 12 mo | 22.71 ± 4.41 | 113.60 ± 110.53 | 0.007 |

| BMs | 3 mo | 4.07 ± 1.90 | 5.60 ± 1.24 | 0.016 |

| 6 mo | 3.21 ± 0.89 | 4.20 ± 1.47 | 0.038 | |

| 12 mo | 2.43 ± 0.85 | 3.60 ± 1.35 | 0.010 | |

| WIS | 3 mo | 4.14 ± 1.41 | 5.60 ± 1.60 | 0.015 |

| 6 mo | 1.86 ± 1.29 | 3.87 ± 1.55 | 0.001 | |

| 12 mo | 1.36 ± 0.63 | 3.53 ± 2.00 | 0.001 | |

| WCS | 3 mo | 2.71 ± 2.30 | 4.33 ± 3.83 | 0.183 |

| 6 mo | 2.64 ± 2.50 | 5.07 ± 4.06 | 0.063 | |

| 12 mo | 2.36 ± 2.13 | 6.40 ± 5.16 | 0.012 | |

| 24 mo | 1.86 ± 1.46 | 6.60 ± 5.42 | 0.005 | |

| GIQLI | 3 mo | 106.57 ± 5.79 | 88.27 ± 12.26 | < 0.001 |

| 6 mo | 114.50 ± 7.59 | 95.13 ± 14.87 | < 0.001 | |

| 12 mo | 119.79 ± 8.24 | 97.60 ± 18.38 | < 0.001 | |

| 24 mo | 122.21 ± 6.85 | 98.47 ± 18.09 | < 0.001 | |

| ABS | 3 mo | 1.29 ± 0.83 | 1.53 ± 0.83 | 0.429 |

| 6 mo | 0.86 ± 0.77 | 1.67 ± 0.82 | 0.011 | |

| 12 mo | 0.86 ± 0.66 | 2.07 ± 0.88 | < 0.001 | |

| 24 mo | 0.79 ± 0.70 | 2.27 ± 1.16 | < 0.001 | |

| NRS | 3 mo | 2.50 ± 1.29 | 3.27 ± 1.34 | 0.127 |

| 6 mo | 2.21 ± 1.47 | 3.53 ± 2.00 | 0.054 | |

| 12 mo | 1.14 ± 0.86 | 3.93 ± 2.92 | 0.003 | |

| 24 mo | 1.07 ± 0.62 | 4.07 ± 3.04 | 0.002 |

At 1 year after surgery, barium enema examinations were performed in all patients of both groups. The barium emptying times were 22.71 ± 4.41 h and 113.60 ± 110.53 h in the bypass plus colostomy group and the bypass group, respectively. The former group was significantly better than the latter group (P = 0.007). In the bypass group, barium emptying time ≥ 72 h was seen in eight (53.33%) patients. In contrast, the longest barium emptying time was 30 h in the bypass plus colostomy group and did not exceed 72 h (P = 0.002).

Primarily, constipation occurs in the aged population and shows increased incidence and severity with aging. Aged patients over 70 years often have varying degrees of accompanying cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases and cannot tolerate some major surgeries. In our study, the preserved length of the ileocecal junction was determined in reference to Wei’s study[31] in which the lengths of the preserved cecum were 2-3 cm distal to the upper edge of the ileocecal junction. All surgeries in the 29 patients were successful. The surgical procedures were the same in both groups except for the cecorectal anastomosis, for which side-side anastomosis was used in the bypass group, while end-side anastomosis and colostomy were used in the bypass plus colostomy group. The preoperative characteristics of the patients were not significantly different between the two groups. Water and fluid diet could be started 24 h after surgery. No obvious abdominal pain was reported after surgery, and the signs of early recovery of intestinal function were noted. The follow-up data showed there was no intestinal obstruction due to adhesions that required surgery.

The results obtained in this study for the treatment of slow transit constipation in an aged population with SCBCAC are very satisfactory. The quality of life has been improved significantly after operations in all the patients. This indicates that these two surgeries have advantages, including minimal trauma, fast recovery, and safe and feasible procedures. There are some explanations for these good results. The first is that we selected the patients strictly before operation. Rigorous psychological assessment is needed before surgery in order to eliminate the patients with psychological symptoms or with history of mental illness. Also, a careful physiologic assessment is necessary to eliminate other causes of constipation, such as organic colon disease, outlet obstruction syndrome, mixed constipation, or small intestinal dysfunction. The other possible reason for the results is the innovation in operative procedures. The procedure of SCBCAC can be manipulated simply and has characteristic features of less invasion and good effect. It also should intuitively require shorter operation time and less risk of contamination during surgery so that the aged population could be well-tolerated and compatible with this procedure.

We found that WCS and GIQLI at 3, 6, 12, and 24 mo after surgery significantly improved compared with the values before surgery in both groups. In the bypass plus colostomy group, ABS significantly improved at 3, 6, 12, and 24 mo after surgery compared with that before surgery. Compared with NRS before surgery, NRS improvement was not noted at 3 and 6 mo but was evident at 12 and 24 mo after surgery. In the bypass group, NRS did not improve at 3, 6, 12, and 24 mo after surgery compared with that before surgery. ABS improvement was seen at 3 and 6 mo but disappeared at 12 and 24 mo after surgery. These results suggest that the efficacy of the bypass plus colostomy is better than that of the bypass group. The reasons for these observations may be that SCBAC cannot improve but can actually worsen symptoms of abdominal pain and bloating.

Based on changes in WIS and BM, we noted that the number of BMs increased somewhat in both groups; however, the movements appeared to decrease over time. These results indicate that the number of BMs at 6 or 12 mo after surgery was lower in the bypass plus colostomy group than in the bypass group. WIS was relatively low in both groups 3 mo after surgery and appeared to decrease over time. Obviously, the WIS improvements at 3, 6, and 12 mo after surgery were significantly better in the bypass plus colostomy group than in the bypass group. The above-noted results suggest that the isolated bypass surgery cannot improve the symptoms of abdominal pain and bloating but can worsen the symptoms of rectal discomfort and increase the number of BMs.

In terms of the changes in WCS, GIQLI, ABS, and NRS at 3, 6, 12, and 24 mo after surgery, we noted that WCS was not significantly different at 3 and 6 mo after surgery between the two groups but that it improved in the bypass plus colostomy group and worsened in the bypass group overtime. WCS at 12 and 24 mo after surgery was better in the bypass plus colostomy group than in the bypass group. In the bypass plus colostomy group, GIQLI at 3 mo after surgery significantly improved and continued to improve over time, eventually reaching the average level of the healthy population. In the bypass group, GIQLI improved without significance. At 6, 12, and 24 mo after surgery, GIQLI was significantly better in the bypass plus colostomy group than in the bypass group. ABS and NRS were not different at 3 mo after surgery, but these parameters continued to improve in the bypass plus colostomy group but conversely worsened in the bypass group over time. At 12 and 24 mo after surgery, ABS and NRS became significantly different between the two groups. In terms of the incidence rates of postoperative abdominal pain and bloating, the incidence rates of severe abdominal bloating were 0 vs 46.67% (7/15) between the bypass plus colostomy group and the bypass group, and the incidence rates of severe abdominal pain were 0 vs 40% (6/15), respectively, between the bypass plus colostomy group and the bypass group. These results suggest that bypass plus colostomy has more advantages in improving the symptoms of constipation, relieving abdominal pain and bloating, and improving the quality of life in aged patients.

What are the causes of abdominal pain, abdominal bloating, rectal discomfort, and increased BMs after surgery? To address these questions, we performed barium enema examinations in these patients at 1 year after surgery and compared the barium emptying times between the two groups. The barium emptying time was significantly shorter in the bypass plus colostomy group than in the bypass group. Moreover, the barium retention sites were in the excluded colon rather than in the small intestine. Further analysis of these data revealed that the longest emptying times were 30 h and 360 h in the bypass plus colostomy group and the bypass group, respectively (shown in Figures 2 and 3). Moreover, the barium emptying times were > 72 h in eight of 15 patients of the bypass group. Therefore, we postulated that postoperative abdominal bloating may be caused by undigested food entering the excluded colon, which produces gas and that postoperative abdominal pain may be caused by food-residue-stimulated peristalsis or even intestinal spasm. The feces in the excluded colon will cause a desire for defecation and rectal discomfort, but the amount of defecation each time is small, and the patient experiences a feeling of incomplete defecation. These symptoms reduce patient quality of life. To this end, we recommend using subtotal colonic bypass plus colostomy rather than an isolated bypass of the colon for the treatment of refractory constipation in aged patients.

Of course, there is no denying that colostomy may bring a little inconvenience to the patients’ daily life compared with healthy people, but unlike other permanent colostomy, the colostomy in SCBCAC does not need to excrete a large amount of stool every day. In our study, the healing of the abdominal wall stoma was favorable. A small amount of intestinal fluid or mucus was drained every 1-3 d, but the drainage amount gradually decreased over time. No ulcers or hemorrhages were seen in the skin around the stoma because no feces were discharged from it. The daily life of patients was not negatively affected. Obviously, colostomy for benign disease did not influence quality of life in aged population. However, this could not be accepted for a younger patient population. Also, there is a problem that tumor occurrence might be increased in the nonfunctional colon and further research is needed to confirm this.

This work is a retrospective single-center study and has certain limitations. We will further develop a multicenter randomized controlled study. Meanwhile, we will expand the sample size and continue long-term follow-up to further evaluate the efficacy of the subtotal colonic bypass plus colostomy.

Laparoscopic SCBCAC is an effective procedure for the treatment of slow transit constipation and is particularly suitable for aged people in poor physical condition who are not suitable for subtotal colonic resection. The efficacy of laparoscopic SCBCAC is superior to that of SCBAC in the aged population.

Constipation affects more than 30% of the aged population and seriously alters the life quality of patients. In terms of treatments for constipation, surgical treatment is a common approach for treatment of intractable slow transit constipation, especially for those with poor responses to conservative treatment. This study offers a better procedure for the treatment of slow transit constipation in an aged population.

Although the current surgical methods have good efficacy in the treatment of slow transit constipation, they are not suitable for aged patients or patients in poor physical condition because of the large wound produced and the length of the operation; these patients need non-surgical treatments. After long-term treatment with oral laxative agents, patients become nonresponsive to these agents and have to undergo enema administration periodically to alleviate their constipation. Some patients cannot tolerate the suffering of constipation and have to choose ileostomy.

The main aim of this study is to compare the efficacy, improved quality of life, and prognosis in patients undergoing either subtotal colonic bypass with antiperistaltic cecoproctostomy (SCBAC) or subtotal colonic bypass plus colostomy with antiperistaltic cecoproctostomy (SCBCAC) for the treatment of slow transit constipation.

Aged patients between October 2010 and October 2014, who had slow transit constipation, were hospitalized and underwent laparoscopic surgery in our institute and were divided into two groups: the bypass group and the bypass plus colostomy group. The following preoperative and postoperative clinical data were collected: gender, age, body mass index, operative time, first flatus time, length of hospital stay, bowel movements (BMs), Wexner fecal incontinence scale, Wexner constipation scale (WCS), gastrointestinal quality of life index (GIQLI), numerical rating scale for pain intensity (NRS), abdominal bloating score (ABS), and Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications (CD) before surgery and at 3, 6, 12, and 24 mo after surgery.

All patients successfully underwent laparoscopic surgery without open surgery conversion or surgery-related death. The operative time and blood loss were significantly less in the bypass group than in the bypass plus colostomy group. No significant differences were observed in first flatus time, length of hospital stay, or complications with CD > 1 between the two groups. No patients had fecal incontinence after surgery. At month 3, 6, and 12 after surgery, the number of BMs was significantly less in the bypass plus colostomy group than in the bypass group. The parameters at month 3, 6, 12, and 24 after surgery in both groups significantly improved compared with the preoperative conditions, except for NRS at month 3 and 6 after surgery in both groups, ABS at month 12 and 24 after surgery, and NRS at month 12 and 24 after surgery in the bypass group. WCS, GIQLI, NRS, and ABS significantly improved in the bypass plus colostomy group compared with the bypass group at month 3, 6, 12, and 24 after surgery except WCS, NRS at month 3, 6 after surgery and ABS at month 3 after surgery. At 1 year after surgery, a barium enema examination showed that the emptying time was significantly better in the bypass plus colostomy group than in the bypass group.

We draw a conclusion from this study that laparoscopic SCBCAC is an effective and safe procedure for the treatment of slow transit constipation in an aged population and can improve the prognosis significantly. Its clinical efficacy is more favorable compared with that of SCBAC. Laparoscopic SCBCAC is a better procedure for the treatment of slow transit constipation in the aged population.

This work is a retrospective single-center study. We will further develop a multicenter randomized controlled study. Meanwhile, we will expand the sample size and continue long-term follow-up to evaluate further efficacy of the subtotal colonic bypass plus colostomy.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P- Reviewer: Eleftheriadis NP, Michel B, Vasilescu C S- Editor: Wang XJ L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Huang Y

| 1. | Stewart WF, Liberman JN, Sandler RS, Woods MS, Stemhagen A, Chee E, Lipton RB, Farup CE. Epidemiology of constipation (EPOC) study in the United States: relation of clinical subtypes to sociodemographic features. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3530-3540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 312] [Cited by in RCA: 303] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Park MI, Shin JE, Myung SJ, Huh KC, Choi CH, Jung SA, Choi SC, Sohn CI, Choi MG; Korean Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility. [Guidelines for the treatment of constipation]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2011;57:100-114. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Knowles CH, Scott M, Lunniss PJ. Outcome of colectomy for slow transit constipation. Ann Surg. 1999;230:627-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Pikarsky AJ, Singh JJ, Weiss EG, Nogueras JJ, Wexner SD. Long-term follow-up of patients undergoing colectomy for colonic inertia. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:179-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ternent CA, Bastawrous AL, Morin NA, Ellis CN, Hyman NH, Buie WD; Standards Practice Task Force of The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. Practice parameters for the evaluation and management of constipation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:2013-2022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lubowski DZ, Chen FC, Kennedy ML, King DW. Results of colectomy for severe slow transit constipation. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:23-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | FitzHarris GP, Garcia-Aguilar J, Parker SC, Bullard KM, Madoff RD, Goldberg SM, Lowry A. Quality of life after subtotal colectomy for slow-transit constipation: both quality and quantity count. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:433-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Thaler K, Dinnewitzer A, Oberwalder M, Weiss EG, Nogueras JJ, Efron J, Vernava AM 3rd, Wexner SD. Quality of life after colectomy for colonic inertia. Tech Coloproctol. 2005;9:133-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sarli L, Costi R, Sarli D, Roncoroni L. Pilot study of subtotal colectomy with antiperistaltic cecoproctostomy for the treatment of chronic slow-transit constipation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1514-1520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Marchesi F, Sarli L, Percalli L, Sansebastiano GE, Veronesi L, Di Mauro D, Porrini C, Ferro M, Roncoroni L. Subtotal colectomy with antiperistaltic cecorectal anastomosis in the treatment of slow-transit constipation: long-term impact on quality of life. World J Surg. 2007;31:1658-1664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Iannelli A, Piche T, Dainese R, Fabiani P, Tran A, Mouiel J, Gugenheim J. Long-term results of subtotal colectomy with cecorectal anastomosis for isolated colonic inertia. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2590-2595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | LEVITAN R, FORDTRAN JS, BURROWS BA, INGELFINGER FJ. Water and salt absorption in the human colon. J Clin Invest. 1962;41:1754-1759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Todd IP. Constipation: Results of surgical treatment. Br J Surg. 1985;72:s12-s13. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yoshioka K, Keighley MR. Clinical results of colectomy for severe constipation. Br J Surg. 1989;76:600-604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | LILLEHEI RC, WANGENSTEEN OH. Bowel function after colectomy for cancer, polyps, and diverticulitis. J Am Med Assoc. 1955;159:163-170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Perrier G, Peillon C, Testart J. [Modifications of the Deloyers procedure in order to perform a cecal-rectal anastomosis without torsion of the vascular pedicle]. Ann Chir. 1999;53:254. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Deloyers L. Suspension of the right colon permits without exception preservation of the anal sphincter after extensive colectomy of the transverse and left colon (including rectum). technic-indications- immediate and late results. Lyon Chir. 1964;60:404-413. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Zinzindohoué F. Difficult colo-colonic or colo-rectal anastomoses: trans-mesenteric anastomoses and anastomoses with right colonic inversion. Ann Chir. 1998;52:571-573. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Ryan J, Oakley W. Cecoproctostomy. Am J Surg. 1985;149:636-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sarli L, Costi R, Iusco D, Roncoroni L. Long-term results of subtotal colectomy with antiperistaltic cecoproctostomy. Surg Today. 2003;33:823-827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Marchesi F, Percalli L, Pinna F, Cecchini S, Ricco’ M, Roncoroni L. Laparoscopic subtotal colectomy with antiperistaltic cecorectal anastomosis: a new step in the treatment of slow-transit constipation. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:1528-1533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Jiang CQ, Qian Q, Liu ZS, Bangoura G, Zheng KY, Wu YH. Subtotal colectomy with antiperistaltic cecoproctostomy for selected patients with slow transit constipation-from Chinese report. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:1251-1256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Iannelli A, Fabiani P, Mouiel J, Gugenheim J. Laparoscopic subtotal colectomy with cecorectal anastomosis for slow-transit constipation. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:171-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sarli L, Iusco D, Costi R, Roncoroni L. Laparoscopically assisted subtotal colectomy with antiperistaltic cecorectal anastomosis. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:1493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sarli L, Iusco D, Violi V, Roncoroni L. Subtotal colectomy with antiperistaltic cecorectal anastomosis. Tech Coloproctol. 2002;6:23-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wang Y, Zhai C, Niu L, Tian L, Yang J, Hu Z. Retrospective series of subtotal colonic bypass and antiperistaltic cecoproctostomy for the treatment of slow-transit constipation. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2010;25:613-618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Agachan F, Chen T, Pfeifer J, Reissman P, Wexner SD. A constipation scoring system to simplify evaluation and management of constipated patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:681-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 818] [Cited by in RCA: 851] [Article Influence: 29.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Eypasch E, Williams JI, Wood-Dauphinee S, Ure BM, Schmülling C, Neugebauer E, Troidl H. Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index: development, validation and application of a new instrument. Br J Surg. 1995;82:216-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 852] [Cited by in RCA: 883] [Article Influence: 29.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Downie WW, Leatham PA, Rhind VM, Wright V, Branco JA, Anderson JA. Studies with pain rating scales. Ann Rheum Dis. 1978;37:378-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1387] [Cited by in RCA: 1312] [Article Influence: 27.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD, de Santibañes E, Pekolj J, Slankamenac K, Bassi C. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009;250:187-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6210] [Cited by in RCA: 8616] [Article Influence: 538.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wei D, Cai J, Yang Y, Zhao T, Zhang H, Zhang C, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Cai F. A prospective comparison of short term results and functional recovery after laparoscopic subtotal colectomy and antiperistaltic cecorectal anastomosis with short colonic reservoir vs. long colonic reservoir. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15:30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |