Published online Jun 14, 2018. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i22.2400

Peer-review started: March 20, 2018

First decision: March 30, 2018

Revised: April 5, 2018

Accepted: May 5, 2018

Article in press: May 5, 2018

Published online: June 14, 2018

Processing time: 83 Days and 11.6 Hours

To ascertain the prognostic role of the T4 and N2 category in stage III pancreatic cancer according to the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) classification.

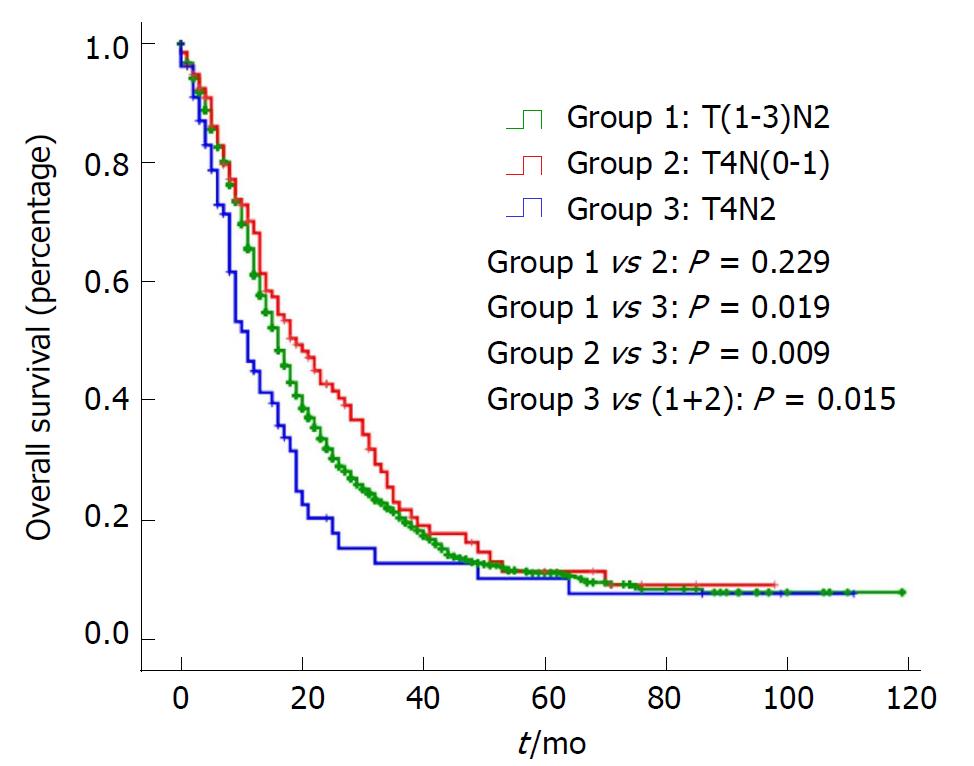

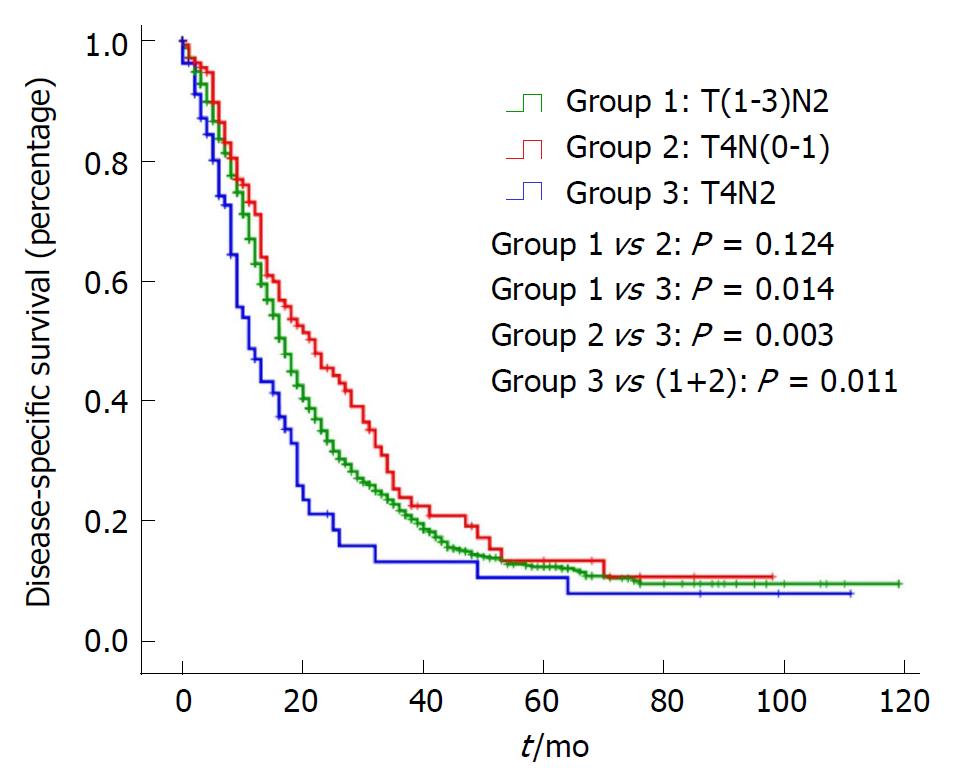

Patients were collected from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database (2004-2013) and were divided into three groups: T(1-3)N2, T4N(0-1), and T4N2. Overall survival (OS) and disease-specific survival (DSS) of patients were evaluated by the Kaplan-Meier method.

For the first time, we found a significant difference in OS and DSS between T(1-3)N2/T4N(0-1) and T4N2 but not between T(1-3)N2 and T4N(0-1). A higher grading correlated with a worse prognosis in the T(1-3)N2 and T4N2 groups.

Patients with stage T4N2 had a worse prognosis than those with stage T(1-3)N2/T4N(0-1) in the 8th edition AJCC staging system for pancreatic cancer. We recommend that stage III should be subclassified into stage IIIA [T(1-3)N2/T4N(0-1)] and stage IIIB (T4N2).

Core tip: The 8th edition American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM criteria for pancreatic cancer incorporated several significant changes of Stage III. T4 and N2 categories were defined as two key parameters of Stage III. Thus, we used the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results database, a population-based database, to evaluate the new changes in pancreatic cancer staging and the prognostic factors.

- Citation: Yu HF, Zhao BQ, Li YC, Fu J, Jiang W, Xu RW, Yang HC, Zhang XJ. Stage III should be subclassified into Stage IIIA and IIIB in the American Joint Committee on Cancer (8th Edition) staging system for pancreatic cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(22): 2400-2405

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v24/i22/2400.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i22.2400

Pancreatic cancer is a challenging disease with significant morbidity and mortality[1,2]. In recent years, the incidence worldwide has increased up to 13/100000 per year due to developments in the detection and management of pancreatic cancer[3]. However, only approximately 4% of patients will live 5 years after diagnosis, and the incidence almost approaches mortality[4,5]. Curative resection is considered the only potential for cure in pancreatic cancer, which can provide prolonged survival; however, even after surgery, the 5-year overall survival rate remains low. Therefore, an accurate staging of the tumor and appropriate treatment strategy is necessary.

The tumor (T), lymph nodes (N), and metastases (M) categories make up the cornerstone of various cancer staging systems of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC)[6]. In the 6th and 7th edition of the AJCC system, stage III pancreatic cancer is only defined as T4/any N/M0, i.e., the tumor involves the celiac axis or the superior mesenteric artery (unresectable primary tumor) no matter the N stage[7]. In contrast, the 8th edition defines T4 and N2 categories as two key parameters of Stage III, which especially highlights the importance of regional lymph nodes. When there is no distant metastasis, tumors with metastasis in ≥ 4 regional lymph nodes, whatever the T category, is also defined as stage III[8]. Clinically, the accurate stage of the pancreatic tumor determines the type of surgical resection, which seriously impacts the patient outcome. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the changes in the AJCC system for defining stage III pancreatic cancer and to identify their prognostic factors.

The Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database (2004-2013) was used for the study. The National Cancer Institute’s SEER*Stat software (Version 8.2.0) was used to identify patients. Patients meeting the following criteria were included: (1) Pathologically confirmed diagnosis; (2) surgical treatment; (3) definite cancer stage III according to the 8th edition of the AJCC criteria; (4) regional lymph node evaluation based on pathologic evidence; (5) first primary tumor; and (6) active type of follow-up. Further exclusion criteria included (1) age < 18 years old; (2) unavailable follow-up data or 0 d of follow-up; and (3) unknown cause of death. Demographics, including age, gender, race, and marital status, were retrieved. Tumor variables included the location of the primary tumor, histological type, and grade. Survival data were extracted at 1-mo intervals for a follow-up period between 1 mo and 110 mo.

The enrolled patients were divided into three groups based on parameters according to the 8th edition AJCC criteria [T(1-3)N2; T4N(0-1); T4N2]. Survival curves for overall survival (OS) and disease-specific survival (DSS) were plotted by Kaplan-Meier analysis according to cancer stages. Univariate analysis with the Cox proportional hazards regression model was performed to explore the difference in prognostic factors between the three groups. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS, version 20 (Armonk, NY, United States). A two-sided P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 1744 pancreatic cancer patients were selected from the SEER database. The age of the patients ranged from 19 to 93 years, with a median age of 63.9 years. The patients’ clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. The majority of the patients (1526, 87.5%) were in Stage T(1-3)N2, followed by Stage T4N(0-1) (138, 7.9%) and Stage T4N2 (80, 4.6%). For the three groups, most of the patients were white and between 60-79 years old. The tumors were mainly located in the head of the pancreas and in Grade II and III.

| Characteristics | Number of patients | ||

| T(1-3)N2 (n = 1526) | T4N(0-1) (n = 138) | T4N2 (n = 80) | |

| Age | |||

| 18-59 | 496 (32.5) | 44 (31.9) | 32 (40) |

| 60-79 | 932 (61.1) | 84 (60.9) | 41 (51.2) |

| > 80 | 98 (6.4) | 10 (7.2) | 7 (8.8) |

| Race | |||

| White | 1295 (84.8) | 110 (79.7) | 64 (80) |

| Black | 131 (8.6) | 16 (11.6) | 7 (8.8) |

| Others | 100 (6.6) | 12 (8.7) | 9 (11.2) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 809 (53.0) | 72 (52.2) | 39 (48.8) |

| Female | 717 (47.0) | 66 (47.8) | 41 (51.2) |

| Grade | |||

| I | 125 (8.2) | 17 (12.3) | 10 (12.5) |

| II | 691 (45.2) | 63 (45.7) | 32 (40) |

| III | 627 (41.1) | 42 (30.4) | 29 (36.3) |

| IV | 13 (0.9) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.5) |

| Unknown | 70 (4.6) | 16 (11.6) | 7 (8.7) |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 504 (33.0) | 43 (31.1) | 29 (36.3) |

| Married | 987 (64.7) | 91 (66.0) | 49 (61.2) |

| Unknown | 35 (2.3) | 4 (2.9) | 2 (2.5) |

| Primary site | |||

| Head of pancreas | 1266 (83.0) | 87 (63.0) | 62 (77.5) |

| Other parts of pancreas | 260 (17.0) | 51 (37.0) | 18 (22.5) |

| Histology | |||

| Adenomas and adenocarcinomas | 809 (53.0) | 74 (53.6) | 39 (48.8) |

| Ductal and lobular neoplasms | 625 (41.0) | 48 (34.8) | 30 (37.5) |

| Others | 92 (6.0) | 16 (11.6) | 11 (13.7) |

Stratified analyses were performed to demonstrate the prognostic impact on OS by the AJCC 8th edition stage III system (Table 2). In Stage T(1-3)N2, the risk of death was significantly higher for patients aged > 80 years old [hazard ratio (HR), 1.343; 95%CI: 1.040-1.734; P = 0.024]. In Stage T4N2, the risk of death was significantly higher for patients aged 60-79 [HR: 1.924; 95%CI: 1.005-3.682; P = 0.048]. Notably, females had a lower risk of death than males in Stage T4N2 [HR: 0.437; 95%CI: 0.222-0.859; P = 0.016]. In addition, a higher grading correlated with a worse prognosis in the T(1-3)N2 and T4N2 groups. For example, the HR-index of Grade IV in Stage T4N2 was 14.118 [95%CI: 1.734-114.943; P = 0.013] compared with 1.000 (Reference) for Grade I, 4.708 (95%CI: 1.375-16.119; P = 0.014) for Grade II, and 9.385 (95%CI: 2.593-33.972; P = 0.001) for Grade III. Relatively few differences were observed in Stage T(1-3)N2. For example, HR was 2.045 for Grade II (P < 0.001), 2.578 for Grade III (P < 0.001) and 3.788 for Grade IV (P < 0.001) when Grade I was referred to 1.000. However, grade was not a significant prognostic factor for Stage T4N(0-1). Furthermore, marital status and the primary site of the tumor had an influence on OS. For example, the risk of death was significantly higher for Stage T(1-3)N2 patients whose tumor was not located in the head of the pancreas (HR: 1.222; 95%CI: 1.039-1.437; P = 0.015), while it was lower for Stage T4N(0-1) patients who were married (HR: 0.560; 95%CI: 0.336-0.935; P = 0.027).

| Characteristics | T(1-3)N2 (n = 1526) | T4N(0-1) (n = 138) | T4N2 (n = 80) | ||||||

| HR | 95%CI | aP | HR | 95%CI | bP | HR | 95%CI | cP | |

| Age | |||||||||

| 18-59 | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| 60-79 | 1.083 | 0.947-1.239 | 0.244 | 1.357 | 0.801-2.298 | 0.256 | 1.924 | 1.005-3.682 | 0.048 |

| > 80 | 1.343 | 1.040-1.734 | 0.024 | 2.223 | 0.847-5.838 | 0.105 | 1.307 | 0.285-5.998 | 0.731 |

| Race | |||||||||

| White | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Black | 1.068 | 0.858-1.328 | 0.558 | 1.155 | 0.573-2.328 | 0.688 | 0.885 | 0.316-2.476 | 0.816 |

| Others | 1.058 | 0.825-1.357 | 0.656 | 0.835 | 0.354-1.970 | 0.681 | 1.678 | 0.575-4.895 | 0.344 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Female | 1.016 | 0.896-1.152 | 0.806 | 1.003 | 0.645-1.561 | 0.989 | 0.437 | 0.222-0.859 | 0.016 |

| Grade | |||||||||

| I | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| II | 2.045 | 1.549-2.701 | 0.000 | 1.240 | 0.594-2.586 | 0.567 | 4.708 | 1.375-16.119 | 0.014 |

| III | 2.578 | 1.952-3.407 | 0.000 | 1.379 | 0.646-2.944 | 0.406 | 9.385 | 2.593-33.972 | 0.001 |

| IV | 3.788 | 1.973-7.272 | 0.000 | - | - | - | 14.118 | 1.734-114.943 | 0.013 |

| Unknown | 2.005 | 1.381-2.911 | 0.000 | 0.484 | 0.146-1.597 | 0.233 | 3.357 | 0.698-16.153 | 0.131 |

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Single | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Married | 0.882 | 0.772-1.007 | 0.064 | 0.560 | 0.336-0.935 | 0.027 | 1.566 | 0.779-3.150 | 0.208 |

| Unknown | 1.001 | 0.649-1.544 | 0.995 | 3.268 | 0.710-15.034 | 0.128 | 0.196 | 0.019-2.007 | 0.170 |

| Primary site | |||||||||

| Head of pancreas | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Other parts of pancreas | 1.222 | 1.039-1.437 | 0.015 | 0.872 | 0.537-1.416 | 0.579 | 1.219 | 0.553-2.688 | 0.624 |

| Histology | |||||||||

| Adenomas and adenocarcinomas | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Ductal and lobular neoplasms | 1.089 | 0.960-1.236 | 0.184 | 1.166 | 0.730-1.864 | 0.52 | 1.617 | 0.746-3.506 | 0.224 |

| Others | 1.017 | 0.782-1.322 | 0.902 | 0.964 | 0.504-1.844 | 0.913 | 1.712 | 0.729-4.020 | 0.217 |

In contrast, little difference was observed in the prognostic impact on DSS for the AJCC 8th edition stage III system. As shown in Table 3, there was no significant difference in DSS for Stage T4N(0-1) patients with different marital statuses.

| Characteristics | T(1-3)N2 (n = 1526) | T4N(0-1) (n = 138) | T4N2 (n = 80) | ||||||

| HR | 95%CI | P | HR | 95%CI | P | HR | 95%CI | P | |

| Age | |||||||||

| 18-59 | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| 60-79 | 1.073 | 0.935-1.232 | 0.314 | 1.357 | 0.776-2.371 | 0.285 | 2.078 | 1.057-4.086 | 0.034 |

| > 80 | 1.319 | 1.013-1.718 | 0.040 | 2.463 | 0.909-6.669 | 0.076 | 1.484 | 0.317-6.949 | 0.616 |

| Race | |||||||||

| White | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Black | 1.028 | 0.818-1.291 | 0.812 | 1.099 | 0.510-2.371 | 0.809 | 0.898 | 0.318-2.536 | 0.839 |

| Others | 1.062 | 0.8123-1.369 | 0.644 | 0.875 | 0.364-2.105 | 0.766 | 1.653 | 0.552-4.949 | 0.369 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Female | 1.006 | 0.884-1.144 | 0.933 | 1.067 | 0.672-1.694 | 0.784 | 0.469 | 0.236-0.933 | 0.031 |

| Grade | |||||||||

| I | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| II | 2.145 | 1.604-2.867 | 0.000 | 1.341 | 0.599-3.005 | 0.476 | 4.537 | 1.314-15.664 | 0.017 |

| III | 2.709 | 2.026-3.623 | 0.000 | 1.496 | 0.653-3.430 | 0.341 | 9.551 | 2.620-34.815 | 0.001 |

| IV | 4.151 | 2.151-8.010 | 0.000 | / | / | / | 12.706 | 1.541-104.769 | 0.018 |

| Unknown | 2.038 | 1.382-3.006 | 0.000 | 0.562 | 0.163-1.937 | 0.361 | 2.463 | 0.461-13.177 | 0.292 |

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Single | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Married | 0.902 | 0.786-1.034 | 0.138 | 0.613 | 0.357-1.054 | 0.077 | 1.820 | 0.888-3.727 | 0.102 |

| Unknown | 1.021 | 0.655-1.590 | 0.928 | 4.531 | 0.961-21.369 | 0.056 | 0.190 | 0.018-1.981 | 0.165 |

| Primary site | |||||||||

| Head of pancreas | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Other parts of pancreas | 1.228 | 1.040-1.450 | 0.015 | 0.761 | 0.456-1.271 | 0.297 | 1.365 | 0.607-3.070 | 0.451 |

| Histology | |||||||||

| Adenomas and adenocarcinomas | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Ductal and lobular neoplasms | 1.066 | 0.937-1.214 | 0.333 | 1.126 | 0.686-1.849 | 0.639 | 1.946 | 0.874-4.335 | 0.103 |

| Others | 1.029 | 0.787-1.344 | 0.837 | 0.953 | 0.485-1.872 | 0.888 | 2.134 | 0.884-5.151 | 0.092 |

In addition, OS and DSS analysis for stage III disease stratified by three groups are presented in Figure 1 and Figure 2. There was no significant difference for OS or DSS between the T(1-3)N2 and T4N(0-1) groups. However, compared with Stage T4N2, both the OS and DSS curves of T(1-3)N2/T4N(0-1) were significantly better [OS: Stage T(1-3)N2 vs T4N2: P = 0.019, Stage T4N(0-1) vs T4N2: P = 0.009; DSS: Stage T(1-3)N2 vs T4N2: P = 0.014, Stage T4N(0-1) vs T4N2: P = 0.003).

Pancreatic cancer is one of the most lethal human cancers, making its staging clinically significant. By analyzing a nationally representative data set, this study further underlines the prognostic relevance of the number of metastatic lymph nodes (N2 vs N1), which allows for a finer stratification of patients in the case of resectable (T1-3) and unresectable (T4) pancreatic cancer. This finding could possibly have relevant repercussions on treatment strategies.

As an aggressive and devastating disease, less than 20% of patients present with localized, potentially curable tumors[2]. In other words, the majority of pancreatic cancers are highly invasive. The most noteworthy finding in the study is that there was no significant difference for OS or DSS between stage T(1-3)N2 and stage T4N(0-1), while they were significantly better than stage T4N2. This indicates that stage III is a heterogeneous group and should be subclassified into stage IIIA [T(1-3)N2/T4N(0-1)] and stage IIIB (T4N2).

The AJCC TNM classification is based on the assessment of resectability[2]. Accordingly, pancreatic cancer is staged. As the basis of cancer staging, tumor size is one of the strongest prognostic factors in pancreatic cancer. T1, T2, and T3 tumors are potentially resectable, whereas T4 tumors are unresectable because they involve the celiac axis or the superior mesenteric artery. In this study, patients undergoing surgical treatment were analyzed to ascertain the prognostic role of the T4 category. In addition, tumor metastasis to regional lymph nodes is a vital step in the progression of cancer[9]. The detection of tumor cells in the lymph nodes is an indication of the spread of the tumor, where some molecules, such as VEGF-C/D and VEGF-R3, play crucial roles as novel key regulators in lymphangiogenesis[10]. There is no doubt that tumor size and lymph node metastases are the two most significant prognostic factors for pancreatic cancer. Apart from these two factors, poor prognostic factors include a high tumor grade and positive margins of resection[11]. This may be why a higher grading was correlated with a worse prognosis in the T(1-3)N2 and T4N2 groups.

On the other hand, the multistep invasion-metastasis cascade for cancer cells is very complex. First, a cancer cell locally invades the surrounding tissue. During metastatic dissemination, it enters the microvasculature of the blood or lymph systems and then survives and translocates to microvessels of distant tissues. Finally, the cancer cell survives and adapts to the foreign microenvironment of distant tissues and forms a secondary tumor[12-14]. Therefore, the different OS and DSS curves suggest that tumors are in the different processes of invasion; that is to say, a tumor at stage T4N2 is further along than stage T(1-3)N2/T4N(0-1). More thorough research is needed for the different pancreatic cancer cell populations.

Regrettably, this study is a mere statistical analysis of patients with pancreatic cancer based on the SEER data, and a more intensive study is required. More detailed information is necessary for us to confirm the relationship between stage III classification and survival.

The 8th edition American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging system for pancreatic cancer has been applied in clinical practice since Jan 1 2018. The definition of stage III consists of TanyN2M0 and T4NanyM0. Our study aimed to evaluate the changes in the AJCC TNM system for defining stage III pancreatic cancer.

The 8th edition AJCC TNM staging system for pancreatic cancer has just been applied in clinical practice for a short while and has not been validated yet. Hence, we used a population-based database to evaluate the rationality of the new staging system.

The primary purpose of this study was to examine the accuracy of classification of stage III. If there was some inadequacy, we would make necessary modifications in order to assure the precise staging.

Patients were selected from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results database (2004-2013) and were divided into three groups: T(1-3)N2, T4N(0-1), and T4N2. Overall survival (OS) and disease-specific survival (DSS) of each group were evaluated by the Kaplan-Meier method.

A significant difference was observed in OS and DSS between T(1-3)N2/T4N(0-1) and T4N2 but not between T(1-3)N2 and T4N(0-1), which indicated stage III was a heterogeneous group. Additionally, a higher grading correlated with a worse prognosis in the T(1-3)N2 and T4N2 groups.

Patients with stage T4N2 had a worse prognosis than those with stage T(1-3)N2/T4N(0-1) in the 8th edition AJCC staging system for pancreatic cancer. Stage III should be subclassified into stage IIIA [T(1-3)N2/T4N(0-1)] and stage IIIB (T4N2), which will improve the staging system greatly.

Larger sample sizes with prospective data should be provided to validate the modification in further research.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Arigami T, Negoi I, Richardson WS S- Editor: Wang XJ L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Yin SY

| 1. | Bardeesy N, DePinho RA. Pancreatic cancer biology and genetics. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:897-909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 848] [Cited by in RCA: 845] [Article Influence: 36.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Hidalgo M. Pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1605-1617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2078] [Cited by in RCA: 2204] [Article Influence: 146.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | McAfee JG. Non-inflammatory applications in vivo of radiolabelled leucocytes: a review. Nucl Med Commun. 1988;9:733-744. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2129] [Cited by in RCA: 2114] [Article Influence: 151.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 4. | Kuhlmann KF, de Castro SM, Wesseling JG, ten Kate FJ, Offerhaus GJ, Busch OR, van Gulik TM, Obertop H, Gouma DJ. Surgical treatment of pancreatic adenocarcinoma; actual survival and prognostic factors in 343 patients. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:549-558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ferrone CR, Brennan MF, Gonen M, Coit DG, Fong Y, Chung S, Tang L, Klimstra D, Allen PJ. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma: the actual 5-year survivors. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:701-706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1471-1474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5537] [Cited by in RCA: 6460] [Article Influence: 430.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bilimoria KY, Bentrem DJ, Ko CY, Ritchey J, Stewart AK, Winchester DP, Talamonti MS. Validation of the 6th edition AJCC Pancreatic Cancer Staging System: report from the National Cancer Database. Cancer. 2007;110:738-744. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 335] [Cited by in RCA: 347] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kamarajah SK, Burns WR, Frankel TL, Cho CS, Nathan H. Validation of the American Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC) 8th Edition Staging System for Patients with Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma: A Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:2023-2030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 24.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 9. | Stacker SA, Achen MG, Jussila L, Baldwin ME, Alitalo K. Lymphangiogenesis and cancer metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:573-583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 600] [Cited by in RCA: 586] [Article Influence: 25.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wissmann C, Höcker M. [VEGF-C, VEGF-D and VEGF-receptor 3: novel key regulators of lymphangiogenesis and cancer metastasis]. Z Gastroenterol. 2002;40:853-856. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Slidell MB, Chang DC, Cameron JL, Wolfgang C, Herman JM, Schulick RD, Choti MA, Pawlik TM. Impact of total lymph node count and lymph node ratio on staging and survival after pancreatectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a large, population-based analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:165-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 286] [Cited by in RCA: 310] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Goh JC, Bose K, Kang YK, Nugroho B. Effects of electrical stimulation on the biomechanical properties of fracture healing in rabbits. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;233:268-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2388] [Cited by in RCA: 2960] [Article Influence: 211.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chaffer CL, Weinberg RA. A perspective on cancer cell metastasis. Science. 2011;331:1559-1564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3059] [Cited by in RCA: 3620] [Article Influence: 258.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fidler IJ. The pathogenesis of cancer metastasis: the ‘seed and soil’ hypothesis revisited. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:453-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3231] [Cited by in RCA: 3324] [Article Influence: 151.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |